Abstract

Background

Difficulties in emotion regulation (DER) are widely considered to underlie anxiety and depression. Given the prevalence of anxiety and depression in adolescents and the fact that adolescence is a key period for the development of emotion regulation ability, it is important to examine how DER is related to anxiety and depression in adolescents in clinical settings.

Methods

In the present study, we assessed 209 adolescents in clinical settings using the Difficulties in Emotion Regulation Scale (DERS) and the Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale (HADS) and examined the associations between six components of DER and 14 symptoms of anxiety and depression. We used network analysis, constructed circular and multidimensional scaling (MDS) networks, and calculated network centrality, bridge centrality, and stability of centrality indices.

Results

The results showed that: (1) The global centrality index shows that the Strategy component (i.e., lack of access to strategies) is the center in the whole network, ranking highest in strength, closeness, betweenness, and expected influence. (2) The MDS network showed a closeness of anxiety and depression symptoms, while Awareness component (i.e., lack of emotional awareness) stayed away from other DER components, but Awareness is close to some depression symptoms. (3) The bridge nodes of three groups, Strategy from DERS, Worry and Relax from anxiety symptoms, and Cheerful and Slow from depression symptoms, had the strongest relationships with the other groups.

Conclusion

Lack of access to strategies remains in the center not only in DER but also in the DER-anxiety-depression network, while lack of awareness is close to depression but not to anxiety. Worrying thoughts and inability to relax are the bridging symptoms for anxiety, while lack of cheerful emotions and slowing down are the bridging symptoms for depression. These findings suggest that making emotion regulation strategies more accessible to patients and reducing these bridging symptoms may yield the greatest rewards for anxiety and depression therapy.

Similar content being viewed by others

Background

Two popular frameworks for emotion regulation

Emotion regulation (ER) is a multidimensional construct that has been proposed to encompass different ER strategies and difficulties with ER [3]. The two perspectives give rise to two distinct theoretical frameworks with corresponding measures.

One framework based on emotion science views emotion regulation as a heterogeneous set of actions designed to influence “which emotions we have, when we have them, and how we experience and express them” [19]. The nature of ER is still left with much confusion, given the elusive definition of “emotion” [20]. What emotions one has and how they are expressed are influenced by the type and timing of the emotion regulation strategy an individual uses [53]. Gross’s process model proposed five points or stages in the emotion generative process at which emotions can be regulated, include situation selection, situation modification, attentional deployment, cognitive change, and response modulation [42]. The Emotion Regulation Questionnaire (ERQ) was developed on this framework with the aim to assess individual differences with primarily concerning discrete strategies for modulating emotional experience: reappraisal and suppression [18].

Another framework of ER, concerning trait-level abilities, proposed four broad facets of emotion regulation by Gratz and Roemer [15],: (a) awareness and understanding, (b) acceptance, (c) the ability to control impulses and follow target behaviors in the presence of negative emotions, and (d) emotion regulation strategies are effective in enhancing the emotional environment. The DERS is considered a comprehensive measure of difficulties in ER and has often been used in research within clinical and treatment settings [21]. Based on this theory, the Difficulties in Emotion Regulation Scale (DERS) was then developed to assess emotion regulation [15], including six subscales: (1) lack of emotional awareness; (2) lack of emotional clarity; (3) difficulty regulating behavior when distressed; (4) difficulty engaging in goal-directed cognition and behavior when distressed; (5) unwillingness to accept certain emotional responses; and (6) lack of access to strategies for feeling better when distressed [21].

DERS has been used more in clinical contexts whilst ERQ has been more commonly used in college samples [52]. These differing descriptions of the measures by the scale developers are notable, as Gratz and Roemer [15] developed the DERS, in large part, to extend the assessment of emotion dysregulation beyond assessing for specific emotion regulation strategies. More precisely, and as noted above, Gratz and Roemer [15] asserted that subjective appraisal of one’s ability to effectively regulate emotions is particularly important when considering the role emotion dysregulation in psychopathology. It seems clear that the construct of emotion dysregulation, in its entirety, must account not only for specific strategies, but also for other processes which impact emotional responding (e.g., identification and understanding of emotions). With such considerations, the use of a more context-dependent measure of emotion regulation difficulties, such as the DERS, may offer advantages over more limited examinations of specific emotion regulation strategies (e.g. cognitive reappraisal and expressive suppression from ERQ) in this study. In addition, DERS show promising internal consistency and validity in a community sample of different demographical groups [38, 45]. Many studies also show that results were consistent across both adolescent and adult samples [28, 59]. These findings provide evidence for the validity in clinical contexts and supply further evidence that emotion regulation difficulties are an excellent transdiagnostic marker of psychopathology risk.

DER and emotion disorders in adolescents

Given the widespread anxiety and depression among adolescents, it is important to understand what contributes to symptoms of anxiety and depression.

A key period for the development of emotion control methods may occur during adolescence [24] and emotion regulation may progress concurrently with physical growth [51]. According to McRae et al. [31], brain development during adolescence may contribute to the development of emotion regulation techniques, indicating a complex interaction between biological and environmental factors. If a person has persistent DER, it can lead to psychosocial impairment [39]. DER represents a potential risk factor for anxiety and depressive symptoms and has been the subject of extensive empirical investigation.

Numerous studies have shown a significant positive correlation between DERS scores (especially total scores) and symptoms of various psychological disorders, including borderline personality disorder [16], Generalized Anxiety Disorder (GAD) [34], substance use disorder [17], social anxiety [47], health-related anxiety [3], posttraumatic stress disorder [9], and bipolar disorder [4, 58].

DER and anxiety

The link between anxiety and emotion dysregulation is common in the literature [8, 48]. Although many studies have found that adults with elevated anxiety symptoms engage in more nonacceptance, suppression, avoidance, worry, and rumination, fewer studies have examined such relationships among anxious adolescents [48]. Research found that dysregulation in emotion could influence the occurrence of anxiety disorders [8].One study found that anxious children displayed more difficulty in employing appropriate emotion regulation strategies than non-anxious children [7]. Weems [60] argued that anxiety disorders in children were best considered as difficulties in regulating anxiety syndromes and negative emotions in general (e.g., experiencing restlessness, worry). Previous research shows that children with anxiety disorders (and other internalizing disorders) tend to have poor emotion understanding, low self-efficacy about their ER abilities, and difficulty expressing certain emotions [48].

Many studies have examined the relationship between various types of anxiety and DERS, although the majority of subjects have been adults. Theoretical, experimental and clinical evidence suggests that patients with GAD are characterized by dysregulated emotion regulation strategies [2]. According to the emotion dysregulation model, GAD is characterized by a rapid, easy and high-intensity experience of emotions [33]. This kind of emotional response leads to difficulties in emotion regulation and is compounded by the difficulty of experiencing clear emotions in people with GAD. Another study showed that DER reliably predicted GAD and the experience of nonclinical panic attacks [55]. Another study also found that the severity of PTSD symptoms was linked to a lack of emotional acceptance, difficulty focusing on target behaviors when upset, difficulty controlling impulses, limited access to effective emotion regulation strategies, and a lack of emotional clarity [54].

DER and depression

Self-reported DER has been linked to depressive symptoms across adolescents [38]. Those with worse emotions and less effective emotion regulation reported more depressive symptoms and problematic behaviors [50]. Negative emotional expression, regarding difficulties in emotion regulation, has also been linked to depressive symptoms [41]. In addition, some studies have shown that DER longitudinally predicts depressive symptoms before adolescence [29]; in another longitudinal study found this to be true for over one year during early adolescence [22].

The relationships among DER components and depression in adolescents may be analyzed as follows [14]. Adolescents may not be aware of their emotions. As a result, they may not use emotion regulation because it inherently needs to know what to be modified. This can make adolescents experience negative emotions with persistence. Even when adolescents are aware and clear about their emotions, they may be unable to accept them. Then the adolescents can only repress the emotions, leading to their more intensive emotions.

Furthermore, negative emotions may make adolescents unable to be fully involved in goal-directed behaviors. Research has shown that those unable to have goal-directed behaviors in negative emotions could lead to depressive symptoms in adolescents [25]. Similarly, adolescents may have a rash, impulsive behaviors in response to negative emotions. Also, studies have shown that impulsivity can predict depressive symptoms in adolescents [62]. In addition, it has been suggested that adolescents with depressive symptom may not possess the strategies required to regulate negative emotions. Studies have shown that adolescents with MDD find it difficult to develop adaptive strategies and utilize them for regulatory purposes [1].

Altogether, these results make clear that various difficulties related to emotion regulation are associated with anxiety and depressive symptoms. Adolescents may experience persistent negative emotions with these problems, making them more likely to suffer from anxiety and depression [49]. The DER components and emotional symptoms can form a complex network, the analysis of which may facilitate our understanding of DER and anxiety & depression.

Network analysis

Thus, network analysis was employed to analyze the relationships among DER components and symptoms of anxiety & depression. We worked bottom-up and did not apply any top-down constructs consistent with standard reductionist biomedical models. In an estimated network structure, the centrality indices represent the overall connectivity of a particular symptom (or component). The central node contributes most to the interconnectedness of the symptoms (or components) in the estimated network structure [6, 46]. When a highly central component is activated, it influences and activates other components, and thus considered to establish the network [57]. In other words, a tightly connected network with many strong connections among the symptoms is considered risky because activation of one symptom can quickly spread to others, leading to more chronic symptoms over time. In addition, we calculated the bridge centrality. Previous research has found that deactivating bridge nodes prevents the spread of comorbidity (i.e., one disorder activating another) [27].

In the present study, we characterized the network structure of DER components and symptoms of anxiety and depression for adolescents in clinical settings. We investigated the network structure and centrality indices, and then checked the stability of the centrality indices for the network, with the aim of gaining insights into the relationship between DERS and anxiety and depression symptoms, which will further expand our knowledge of ER mechanism in psychopathology (anxiety and depression), and provide clinical implications for anxiety and depression therapy.

Method

Participants

The sample consisted of 209 adolescents aged 12 to 18 years that sought clinical aid at a psychiatric hospital between February and May of 2022. Each individual completed the hospital registration procedure, followed by a one-on-one mental health assessment by the hospital psychiatrist. Prior to the mental-health assessment, patient and parents/guardians were briefed on the assessment procedure and scales used, followed by the signed informed consent from both parent/guardian and patient as required by local hospital ethical regulations. The patient was then led to an assessment room under the company of the hospital psychiatrist and asked to complete the Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale (HADS) and the DERS in addition to the routine diagnosis process. When the patient was completed, the psychiatrist checked to ensure that all sections of the HADS and DERS had been completed. All procedures contributing to this work conformed to the ethical standards of the relevant national and institutional human experimentation committees, as well as to the 1975 Declaration of Helsinki (revised 2008). All procedures involved were approved by the IRB of the Seventh People's Hospital of Wenzhou (EC-KY-2022048).

Measures

Hospital anxiety and depression scale (HADS)

The HADS assesses both anxiety and depression, which commonly coexist. The measure is employed frequently due to its simplicity, speed, and ease of use. Very few literate people have difficulty completing it. The HADS contains 14 items, including seven for depressive symptoms (i.e., the HADS-D) and seven for anxiety symptoms (i.e., the HADS-A), focusing on non-physical symptoms. The correlations between the two subscales vary from 0.40 to 0.74 (with a mean of 0.56). The Cronbach's alpha for the HADS-A varies from 0.68 to 0.93 (with a mean of 0.83) and for the HADS-D from 0.67 to 0.90 (with a mean of 0.82). The sensitivity and specificity for both is approximately 0.80 [5]. Many studies conducted around the world have confirmed that the measure is valid when used in a community setting or primary care medical practice.

Difficulties in emotion regulation scale (Chinese version)

The scale of DERS is a 36-item self-report measure. It contains six factors: nonacceptance of emotional responses, difficulty engaging in goal-directed behavior, impulse control problems, lack of emotional awareness, limited access to emotion regulation strategies, and lack of emotional clarity. Higher scores indicate more difficulty in emotion regulation. The Cronbach’s alpha of the scale and six subscales ranges from 0.88 to 0.96, and test–retest reliability from 0.52 to 0.77. Confirmatory factor analysis has shown the following fit indices: X2/df = 1.05, AGFI = 0.87, GFI = 0.90, NFI = 0.94, CFI = 0.99, TLI = 0.99, NNFI = 0.9, RMSEA = 0.015, and KMK = 0.06 [30].

Network analysis

We constructed the network using Gaussian graphical models (GGMs) via the R package (R Core Team version 4.1.3) qgraph (version 1.9.2) [10]. GGMs estimate many parameters (i.e., 20 nodes need to estimate 190 parameters: 20 threshold parameters and 20 * 19/2 = 190 paired correlation parameters), likely leading to false positive edges. Therefore, GGMs are usually regularized by a graphical lasso, resulting in a sparse (i.e., resolved) network with as few edges as possible to explain the correlation or covariance between nodes [13]. The R package qgraph was used to calculate and visualize the networks. We also measured the centrality and stability of the established network. The R package qgraph and estimateNetwork automatically implement the glasso regularization, combined with an extended Bayesian information criterion (EBIC) model [12].

In network terminology, symptoms of anxiety, depression and DER components are “nodes” and the relationships among the nodes are “edges.” The edge between two nodes represents the regularized partial correlation coefficient, and the thickness indicates the association's magnitude. The graphical lasso algorithm makes all edges with small partial correlations shrink to zero. It thus facilitates the interpretation and establishment of a stable network, solving traditional lost-power issues that emerge from examining all partial correlations for statistical significance [11]. For the present network, we divided the components into three groups or communities: anxiety (seven symptoms), depression (seven symptoms), and DER (six components).

Most network studies in psychopathology have used the FR algorithm to plot graphs, where the node locations don’t have meanings in space but to position them in a way that facilitates viewing network edges and clustering structures [27]. We used the "circle" layout for easier viewing, which places all nodes in a single circle, with each group (or community) put in separate circles (see Fig. 1a). In addition, we employed a multi-dimensional scaling (MDS) approach to display the network (see Fig. 1b). MDS expresses the proximity between variables as distances between nodes in a low-dimensional space, which is particularly useful for understanding networks, as the distances drawn between nodes can be interpreted as Euclidean distances [27].

The network structure based on 209 adolescents. The network structure is a network of EBICglasso based on GGM. Green edges represent positive correlations, and red edges indicate negative correlations. The thickness of the edge reflects the magnitude of the correlation. a The network is with “circle” layout for easy viewing. It is important to note that the node positions don’t indicate Euclidean distances. The value (weight) on the edge indicates regression coefficient after regularization. b The network is with MDS, showing proximities among variables as distances between points in a low-dimensional space

Centrality We calculated several indices of node centrality to identify the most central symptom or component of the network. For each node, we calculated strength (i.e., the absolute value of the edge weights connected to the node), proximity (i.e., the average distance of the node from all other nodes in the network), spacing (i.e., the number of times a node lies on the shortest path between two other nodes), and expected influence (i.e., the sum of the edge weights connected to the node). In addition, node bridge strength is defined as the sum of the values of all edges connecting a particular node in a community to nodes in other communities; it is calculated with R-package networktools [27]. A higher node bridge strength value indicates more likely influence other groups.

Stability of centrality indices We investigated the stability of the centrality index by estimating a network model based on a subset of the data and a case-removal bootstrap (N = 1000). We considered the centrality index unstable if the correlation value decreased substantially with participant removal. The robustness of the network was assessed by the R-package bootnet using bootstrap methods [11]. This stability is calculated using the CS coefficient. It calculates the maximum proportion of cases with 95% certainty to retain correlations with raw centrality above 0.7 (default).

Results

All the adolescents were included in the analysis. The students’ average age was 15.51 years (SD = 1.36). Descriptive statistics for these adolescents can be found in Table 1.

In the entire network, approximately 51.57% of all 190 network edges were set to zero by the EBICglasso algorithms. Figure 1 displays the network of DER components and anxiety and depression symptoms. Figure 1a displays an easily viewable circular network with weights on each edge. For example, the strongest edge (weight = 0.45) among the anxiety symptoms was between BttFootnote 1 (Butterfly: “I get sort of a frightened feeling, like butterflies in the stomach”) and Pnc (Panic: “I get sudden feelings of panic”). Among depression symptoms, the strongest edge (weight = 0.27) was between Chr (Cheerful: “I feel cheerful”) and Fnn (Funny: “I can laugh and see the funny side of things”). For DER components, the strongest edge (weight = 0.34) was between STR (“Limited access to emotion regulation strategies”) and GOL (Goal: “Difficulties engaging in goal-directed behavior”). Particularly, there was a strong connection (weight = 0.33) between Rlx (Relax: “I can sit at ease and be relaxed”) from the anxiety group and Chr from depression. Here, the weight indicates regression coefficient after regularization.

Figure 1b displays the MDS network. Highly-related nodes appear close together, whereas weakly-related nodes are farther apart. The node connections were closer within (vs. between) the anxiety, depression and DER communities, demonstrating their relative independence from one other. Among the DERS components, AWR (Awareness) stays apart from other components including CLR (Clarity), STR (Strategy), GOL (Goal), IMP (Impulse), and NNC (Non-acceptance). In the anxiety-depression network, some of the nodes were intertwined, such as Rlx (Relax: “I can sit at ease and be relaxed”) and Chr (Cheer: “I feel cheerful”), which echoes previous studies of anxiety and depression comorbidity that employed network analysis [43, 61].

Centrality indices

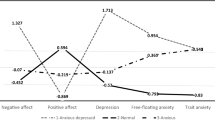

For the centrality indices, the values were scaled (i.e., normalized) relative to the highest value for each measure. Figure 2 shows the centrality indices, ordered by Expected Influence. STR (“Limited access to emotion regulation strategies”) from the DER components was the most central symptom, according to four indices. Frw (Forwrod: “I look forward with enjoyment to things”) from the depression symptoms and Btt (Butterflies: I get a sort of frightened feeling like 'butterflies' in the stomach) from the anxiety symptoms ranked high in their own groups, indicating that these nodes had strong relationships to the other nodes. For closeness and betweenness, Wrr (Worry: “Worrying thoughts go through my mind”) from the anxiety symptoms and Chr (Cheerful: “I feel cheerful”) from depression symptoms ranked the highest, meaning that they were closest to all other nodes in the network and usually stay between two other nodes.

Centrality indices for the nodes of the present network, including those for strength, betweenness, closeness, and expected influence. The full names of the abbreviations can be found in Fig. 1

Bridge centrality indices

We also calculated the bridge centrality indices (see Fig. 3). From four indices (i.e., bridge betweenness, closeness, expected influence, and strength) has the same meaning as mentioned in Session 3.1, but bridge centrality indices only show the influence on other groups. For example, STR (Strategy) in DERS ranked the highest, indicating these nodes had strong connections to anxiety and depression symptoms. CLR (Clarity) also has a relative strong connection to anxiety and depression symptoms. In other two groups, Wrr (Worry) and Rlx (Relax) from anxiety symptoms rank highest (strongest nodes connecting other groups) in among anxiety symptoms, and Chr (Cheerful) and Slw (Slow: I feel as if l am slowed down) from depression symptoms.

Estimated bridge centrality indices for the present network, including bridge strength, betweenness, closeness, and expected influence. The full names of the abbreviations for the nodes can be found in Fig. 1

Stability of the centrality indices

Figure 4 shows the average correlations of centrality indices between the full sample and the selected cases. The rationale is to calculate maximum drop proportions to retain correlation of 0.7 in at least 95% of the samples. In this study, the CS coefficient indicated that the betweenness (CS(cor = 0.7) = 0.208), indicating that we can drop 20.8% of the samples to retain correlation of 0.7 with the full sample. For other indices, closeness (CS(cor = 0.7) = 0.208), strength (CS(cor = 0.7) = 0.283) and expected influence (CS(cor = 0.7) = 0.283). The CS coefficient value should preferably be above 0.5 and be at least 0.25. Therefore, strength and expected influence are relative more stable.

Discussion

Depression and anxiety, widely viewed as the result of difficulties with emotion regulation [35], are becoming more severe in adolescents. Considering the relationship between DER and mood disorders, it is appropriate to put anxiety, depression, and DER components into a single network, where the DERS is the ability of ER while the anxiety and depression are the symptoms. An advantage of network analysis is that the discovery of dimensions does not require an a priori definition. Anchored in the network perspective, this study illustrated the node pathways, central indices, and central bridging indices for adolescents' DER and anxiety-depression networks. Therefore, we can infer the mechanism between the ER ability and Anxiety-depression symptoms.

Global centrality index shows Strategy (i.e., lack of access to strategies) is the center in whole network, ranking highest in strength, closeness, betweenness and expected influence. It should be noted that the Strategy subscale in DERS and strategies in ERS is different both in direction and content. According to Gratz and Roemer [15], Strategy is connected to “the belief that there is little that can be done to regulate emotions effectively once an individual is upset”, which makes it difficult to manage and control emotions [40]. Effective emotion regulation strategies may be especially important during adolescence, due to the increase in stress and rate of depression during this period. A meta-analysis has shown that that emotion regulation strategies are related to life satisfaction, positive affect, depression, anxiety, and negative affect [26, 32]. Research has shown that the ability to regulate one’s emotions is a key target intervention across various mental health presentations [36], and cognitive behavioral therapy for emotional disorders often relies on emotion regulation strategies to be successful [44]. As one study has found that participants diagnosed with at least one anxiety disorder or MDD who report high DERS scores still manage to effectively reduce induced negative emotions in 3 min when required to use emotion strategies [37]. Further, as the bridge centrality indices shows, the Strategy and Worry ranks the highest in connecting to the other sub-networks. Strategy is strongly related to Worry in anxiety sub-network, while Worry is strongly connected to the symptoms in anxiety and depression. Therefore, Strategy is the key node in DERS and making it more accessible to it may have positive influence to anxiety and depression (through Worry). It is reasonable for clinical practitioners not only to instruct patients with new emotion regulation strategies, but also encourage them to pay attention to and engage with optimal individual strategies when faced with Worry (“Worrying thoughts go through my mind”).

In addition, MDS approach (showing in Fig. 1b) allows for a more detailed representation of the interrelationships between items and the mutual positioning. These three sub-networks of anxiety, depression and DERS are relative independent with each other, but there are some intertwines, indicating the inner connections. The use of MDS approach should be encouraged in the future as it indicates the spatial relationships of nodes. According to the positioning in Fig. 1b, the Awareness is far away from other abilities in DERS, which is echoed by previous research [3, 15, 21] but stay close to the item of Enjoy (“I still enjoy the things l used to enjoy”) and Forword (“I look forward with enjoyment to things”) in Depression sub-network, which seems to indicate difficulties in awareness of one’s emotion may maintain the symptoms such as lack of enjoyment and thus maintain depression. Such results were inconsistent with previous research, which showed no direct relationship between emotional awareness and depressive symptoms, though emotional awareness yielded a significant mediation effect through total adaptive ER strategies on higher depressive symptoms [56]. In addition, the Awareness from DERS was not significantly associated with any of the symptoms of anxiety, supported by some (but not all) of previous research show “With the exception of ‘lack of emotional awareness’, social anxiety disorders participants reported significantly higher levels of ER difficulties when controlling for depression” [23].

Limitations

Several limitations of this study will guide our future work. First, a cross-sectional design was used to construct DER and anxiety-depression networks. Therefore, the present study cannot be used to determine whether anxiety and depression symptoms cause DER components and vice versa. Future work will use a longitudinal approach with repeated measures of anxiety-depression and DER components to clarify the causal relationship between the two.

Second, the potential pathways found between the components may be limited to the DERS and HADS scales used. When we change the framework of emotion regulation from the clinical situational model to basic emotion science, the network structure is quite different. This diversity may lead to different findings and even some contradictory results.

Third, the sample size of this study was only 209 from the local psychiatric hospital. Future studies should increase the sample size and its variability to obtain a more comprehensive and stable network structure for more reliable conclusions.

Fourth, more scales than anxiety and depression should be included. Comorbidity is very common in psychopathological disorders, so symptoms such as subjective feelings of restlessness and impulsivity may also be found in other disorders such as ADHD. With more assessments, we will have a better understanding of the mechanisms of emotional dysfunction.

Conclusions

The present study adds to the literature on how anxiety and depressive symptoms are related to DER components in adolescents in clinical settings. Lack of access to strategies stays in the center not only in DER but also in the network of DER-anxiety-depression. Lack of awareness is close to depression but not to anxiety. Worrying thoughts and inability to relax are the bridging symptoms for anxiety, while lack of cheerful emotions and slowing down are the bridging symptoms for depression. These findings suggest that reducing these bridging symptoms through therapy for anxiety and depression may yield the greatest benefits by making emotion regulation strategies more accessible to patients.

Notes

Following, the node labels with abbreviations will be in italics.

References

Aldao A, Nolen-Hoeksema S, Schweizer S. Emotion-regulation strategies across psychopathology: A meta-analytic review. Clin Psychol Rev. 2010;30(2):217–37.

Amstadter A. Emotion regulation and anxiety disorders. J Anxiety Disord. 2008;22(2):211–21. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.janxdis.2007.02.004.

Bardeen JR, Fergus TA. An examination of the incremental contribution of emotion regulation difficulties to health anxiety beyond specific emotion regulation strategies. J Anxiety Disord. 2014;28(4):394–401. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.janxdis.2014.03.002.

Becerra R, Cruise K, Murray G, Bassett D, Harms C, Allan A, Hood S (2013) Emotion regulation in bipolar disorder: Are emotion regulation abilities less compromised in euthymic bipolar disorder than unipolar depressive or anxiety disorders?

Bjelland I, Dahl AA, Haug TT, Neckelmann D. The validity of the Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale: An updated literature review. J Psychosom Res. 2002;52(2):69–77.

Borsboom D. A network theory of mental disorders. World Psychiatry. 2017;16(1):5–13.

Carthy T, Horesh N, Apter A, Edge MD, Gross JJ. Emotional reactivity and cognitive regulation in anxious children. Behav Res Ther. 2010;48(5):384–93. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.brat.2009.12.013.

Cisler JM, Olatunji BO, Feldner MT, Forsyth JP. Emotion regulation and the anxiety disorders: an integrative review. J Psychopathol Behav Assess. 2010;32(1):68–82. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10862-009-9161-1.

Ehring T, Quack D. Emotion regulation difficulties in trauma survivors: The role of trauma type and PTSD symptom severity. Behav Ther. 2010;41(4):587–98.

Epskamp S, Cramer AO, Waldorp LJ, Schmittmann VD, Borsboom D. qgraph: Network visualizations of relationships in psychometric data. J Stat Softw. 2012;48:1–18.

Epskamp S, Fried EI. A tutorial on regularized partial correlation networks. Psychol Methods. 2018;23(4):617.

Foygel R, Drton M. Extended Bayesian information criteria for Gaussian graphical models. Adv Neural Inform Process Syst. 2010;23:88.

Friedman J, Hastie T, Tibshirani R. Sparse inverse covariance estimation with the graphical lasso. Biostatistics. 2008;9(3):432–41.

Gonçalves SF, Chaplin TM, Turpyn CC, Niehaus CE, Curby TW, Sinha R, Ansell EB. Difficulties in emotion regulation predict depressive symptom trajectory from early to middle adolescence. Child Psychiatry Hum Dev. 2019;50:618–30.

Gratz KL, Roemer L. Multidimensional assessment of emotion regulation and dysregulation: development, factor structure, and initial validation of the difficulties in emotion regulation scale. J Psychopathol Behav Assess. 2004;26(1):41–54. https://doi.org/10.1023/B:JOBA.0000007455.08539.94.

Gratz KL, Rosenthal MZ, Tull MT, Lejuez CW, Gunderson JG. An experimental investigation of emotion dysregulation in borderline personality disorder. J Abnorm Psychol. 2006;115(4):850.

Gratz KL, Tull MT. Emotion regulation as a mechanism of change in acceptance-and mindfulness-based treatments. Assessing Mindfulness Acceptance Processes Clients. 2010;2:107–33.

Gross JJ. Antecedent-and response-focused emotion regulation: divergent consequences for experience, expression, and physiology. J Pers Soc Psychol. 1998;74(1):224.

Gross JJ. Emotion regulation: affective, cognitive, and social consequences. Psychophysiology. 2002;39(3):281–91. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0048577201393198.

Gross JJ, Feldman Barrett L. Emotion generation and emotion regulation: one or two depends on your point of view. Emot Rev. 2011;3(1):8–16. https://doi.org/10.1177/1754073910380974.

Hallion LS, Steinman SA, Tolin DF, Diefenbach GJ. Psychometric properties of the Difficulties in Emotion Regulation Scale (DERS) and its short forms in adults with emotional disorders. Front Psychol. 2018;9:539.

Hatzenbuehler ML, Nolen-Hoeksema S, Erickson SJ. Minority stress predictors of HIV risk behavior, substance use, and depressive symptoms: Results from a prospective study of bereaved gay men. Health Psychol. 2008;27(4):455–62. https://doi.org/10.1037/0278-6133.27.4.455.

Helbig-Lang S, Rusch S, Lincoln TM. Emotion regulation difficulties in social anxiety disorder and their specific contributions to anxious responding: emotion regulation in social anxiety disorder. J Clin Psychol. 2015;71(3):241–9. https://doi.org/10.1002/jclp.22135.

Heller AS, Casey BJ. The neurodynamics of emotion: Delineating typical and atypical emotional processes during adolescence. Dev Sci. 2016;19(1):3–18.

Herres J, James KM, Bounoua N, Krauthamer Ewing ES, Kobak R, Diamond GS. Anxiety-related difficulties in goal-directed behavior predict worse treatment outcome among adolescents treated for suicidal ideation and depressive symptoms. Psychotherapy. 2021;58(4):523.

Hu T, Zhang D, Wang J, Mistry R, Ran G, Wang X. Relation between emotion regulation and mental health: A meta-analysis review. Psychol Rep. 2014;114(2):341–62.

Jones PJ, Mair P, McNally RJ. Visualizing psychological networks: a tutorial in R. Front Psychol. 2018;9:1742. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2018.01742.

Kaufman EA, Xia M, Fosco G, Yaptangco M, Skidmore CR, Crowell SE. The difficulties in emotion regulation scale short form (DERS-SF): validation and replication in adolescent and adult samples. J Psychopathol Behav Assess. 2016;38(3):443–55. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10862-015-9529-3.

Kim J, Cicchetti D. Longitudinal pathways linking child maltreatment, emotion regulation, peer relations, and psychopathology: pathways linking maltreatment, emotion regulation, and psychopathology. J Child Psychol Psychiatry. 2009;51(6):706–16. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1469-7610.2009.02202.x.

Ling D, Nan Z, Xiaobin D. Reliability and validity of difficulties in emotion regulation normal scale in chinese adolescent. Chin J Health Psychol. 2014;22(003):363–6.

McRae K, Gross JJ, Weber J, Robertson ER, Sokol-Hessner P, Ray RD, Gabrieli JD, Ochsner KN. The development of emotion regulation: An fMRI study of cognitive reappraisal in children, adolescents and young adults. Soc Cognit Affect Neurosci. 2012;7(1):11–22.

Menefee DS, Ledoux T, Johnston CA. The importance of emotional regulation in mental health. Am J Lifestyle Med. 2022;16(1):28–31.

Mennin DS. Emotion regulation therapy for generalized anxiety disorder. Clin Psychol Psychother. 2004;11(1):17–29. https://doi.org/10.1002/cpp.389.

Mennin DS, Heimberg RG, Turk CL, Fresco DM (2002) Applying an emotion regulation framework to integrative approaches to generalized anxiety disorder.

Mennin DS, Holaway RM, Fresco DM, Moore MT, Heimberg RG. Delineating components of emotion and its dysregulation in anxiety and mood psychopathology. Behav Ther. 2007;38(3):284–302.

Moore R, Gillanders D, Stuart S. The impact of group emotion regulation interventions on emotion regulation ability: a systematic review. J Clin Med. 2022;11(9):2519.

Neacsiu AD, Smith M, Fang CM. Challenging assumptions from emotion dysregulation psychological treatments. J Affect Disord. 2017;219:72–9. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jad.2017.05.016.

Neumann A, van Lier PAC, Gratz KL, Koot HM. Multidimensional assessment of emotion regulation difficulties in adolescents using the difficulties in emotion regulation scale. Assessment. 2010;17(1):138–49. https://doi.org/10.1177/1073191109349579.

Nolen-Hoeksema S, Aldao A. Gender and age differences in emotion regulation strategies and their relationship to depressive symptoms. Personality Individ Differ. 2011;51(6):704–8.

Pepe M, Nicola M, Moccia L, Franza R, Chieffo D, Addolorato G, Janiri L, Sani G. Limited Access to Emotion Regulation Strategies Mediates the Association Between Positive Urgency and Sustained Binge Drinking in Patients with Alcohol Use Disorder. Int J Mental Health Addict 2022;78: 1–14.

Poon JA, Turpyn CC, Hansen A, Jacangelo J, Chaplin TM. Adolescent substance use & psychopathology: interactive effects of cortisol reactivity and emotion regulation. Cogn Ther Res. 2016;40(3):368–80. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10608-015-9729-x.

Quoidbach J, Mikolajczak M, Gross JJ. Positive interventions: An emotion regulation perspective. Psychol Bull. 2015;141(3):655–93. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0038648.

Ren L, Wang Y, Wu L, Wei Z, Cui L-B, Wei X, Hu X, Peng J, Jin Y, Li F. Network structure of depression and anxiety symptoms in Chinese female nursing students. BMC Psychiatry. 2021;21(1):1–12.

Renna ME, Quintero JM, Fresco DM, Mennin DS. Emotion regulation therapy: A mechanism-targeted treatment for disorders of distress. Front Psychol. 2017;8:98.

Ritschel LA, Tone EB, Schoemann AM, Lim NE. Psychometric properties of the Difficulties in Emotion Regulation Scale across demographic groups. Psychol Assess. 2015;27(3):944–54. https://doi.org/10.1037/pas0000099.

Ruan QN, Chen C, Jiang D-G, Yan WJ, Lin Z. A network analysis of social problem-solving and anxiety/depression in adolescents. Front Psychiatr. 2022; Doi https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyt.2022.921781

Rusch S, Westermann S, Lincoln TM. Specificity of emotion regulation deficits in social anxiety: An internet study. Psychol Psychother Theory Res Pract. 2012;85(3):268–77.

Schneider RL, Arch JJ, Landy LN, Hankin BL. The longitudinal effect of emotion regulation strategies on anxiety levels in children and adolescents. J Clin Child Adolesc Psychol. 2018;47(6):978–91. https://doi.org/10.1080/15374416.2016.1157757.

Selby EA, Anestis MD, Joiner TE. Understanding the relationship between emotional and behavioral dysregulation: Emotional cascades. Behav Res Ther. 2008;46(5):593–611.

Seymour KE, Chronis-Tuscano A, Halldorsdottir T, Stupica B, Owens K, Sacks T. Emotion regulation mediates the relationship between ADHD and depressive symptoms in youth. J Abnorm Child Psychol. 2012;40(4):595–606. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10802-011-9593-4.

Silvers JA, McRae K, Gabrieli JD, Gross JJ, Remy KA, Ochsner KN. Age-related differences in emotional reactivity, regulation, and rejection sensitivity in adolescence. Emotion. 2012;12(6):1235.

Sörman K, Garke MÅ, Isacsson NH, Jangard S, Bjureberg J, Hellner C, Sinha R, Jayaram-Lindström N. Measures of emotion regulation: Convergence and psychometric properties of the difficulties in emotion regulation scale and emotion regulation questionnaire. J Clin Psychol. 2022;78(2):201–17. https://doi.org/10.1002/jclp.23206.

Tull MT, Aldao A. Editorial overview: New directions in the science of emotion regulation. Curr Opin Psychol. 2015;3:iv–x. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.copsyc.2015.03.009.

Tull MT, Barrett HM, McMillan ES, Roemer L. A preliminary investigation of the relationship between emotion regulation difficulties and posttraumatic stress symptoms. Behav Ther. 2007;38(3):303–13. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.beth.2006.10.001.

Tull MT, Stipelman BA, Salters-Pedneault K, Gratz KL. An examination of recent non-clinical panic attacks, panic disorder, anxiety sensitivity, and emotion regulation difficulties in the prediction of generalized anxiety disorder in an analogue sample. J Anxiety Disord. 2009;23(2):275–82. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.janxdis.2008.08.002.

Van Beveren M-L, Goossens L, Volkaert B, Grassmann C, Wante L, Vandeweghe L, Verbeken S, Braet C. How do I feel right now? Emotional awareness, emotion regulation, and depressive symptoms in youth. Eur Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 2019;28(3):389–98. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00787-018-1203-3.

van Borkulo C, Boschloo L, Borsboom D, Penninx BW, Waldorp LJ, Schoevers RA. Association of symptom network structure with the course of depression. JAMA Psychiat. 2015;72(12):1219–26.

Van Rheenen TE, Murray G, Rossell SL. Emotion regulation in bipolar disorder: Profile and utility in predicting trait mania and depression propensity. Psychiatry Res. 2015;225(3):425–32.

Victor SE, Klonsky ED. Validation of a brief version of the difficulties in emotion regulation scale (DERS-18) in Five Samples. J Psychopathol Behav Assess. 2016;38(4):582–9. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10862-016-9547-9.

Weems C. Developmental trajectories of childhood anxiety: Identifying continuity and change in anxious emotion☆. Dev Rev. 2008;28(4):488–502. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.dr.2008.01.001.

Wei Z, Ren L, Wang X, Liu C, Cao M, Hu M, Jiang Z, Hui B, Xia F, Yang Q. Network of depression and anxiety symptoms in patients with epilepsy. Epilepsy Res. 2021;175: 106696.

You J, Leung F. The role of depressive symptoms, family invalidation and behavioral impulsivity in the occurrence and repetition of non-suicidal self-injury in Chinese adolescents: A 2-year follow-up study. J Adolesc. 2012;35(2):389–95.

Funding

This work was supported by the Wenzhou Municipal Science and Technology Bureau (Grant No. Y20210112) and Zhejiang Medical and health Science and Technology Project (Grant No. 2023RC273).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Q-NR conceived and designed the experiments. Y-HC performed the experiments. Q-NR, Y-HC and W-JY wrote and revised the manuscript. All authors contributed to the article. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

The authors assert that all procedures contributing to this work comply with the ethical standards of the relevant national and institutional committees on human experimentation and with the Helsinki Declaration of 1975, as revised in 2008. All procedures involving human subjects/patients were approved by IRB in Wenzhou Seventh People’s Hospital (EC-KY-2022048).

All procedures were performed in accordance with relevant guidelines from declaration of Helsinki statement.

Data Availability

The raw data supporting the conclusion of this article is available, without undue reservation. https://osf.io/2mdqh/

Competing interests

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/. The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver (http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/) applies to the data made available in this article, unless otherwise stated in a credit line to the data.

About this article

Cite this article

Ruan, QN., Chen, YH. & Yan, WJ. A network analysis of difficulties in emotion regulation, anxiety, and depression for adolescents in clinical settings. Child Adolesc Psychiatry Ment Health 17, 29 (2023). https://doi.org/10.1186/s13034-023-00574-2

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s13034-023-00574-2