Abstract

Background

Growing evidence indicates that if disruptive behavior is left unidentified and untreated, a significant proportion of these problems will persist and may develop into problems linked with delinquency, substance abuse, and violence. Research is needed to develop valid and reliable measures of disruptive behavior to assist recognition and impact of treatments on disruptive behavior. The aim of this study was to develop and evaluate the psychometric properties of a scale for disruptive behavior in adolescents.

Methods

Six hundred high school students (50% girls), ages ranged 15–18 years old, selected through multi stage random sampling. Psychometrics of the disruptive behavior scale for adolescents (DISBA) (Persian version) was assessed through content validity, explanatory factor analysis (EFA) using Varimax rotation and confirmatory factor analysis (CFA). The reliability of this scale was assessed via internal consistency and test–retest reliability.

Results

EFA revealed four factors accounting for 59% of observed variance. The final 29-item scale contained four factors: (1) aggressive school behavior, (2) classroom defiant behavior, (3) unimportance of school, and (4) defiance to school authorities. Furthermore, CFA produced a sufficient Goodness of Fit Index > 0.90. Test–retest and internal consistency reliabilities were acceptable at 0.85 and 0.89, respectively.

Conclusions

The findings from this study suggest that the Iranian version of DISBA questionnaire has content validity. Further studies are needed to evaluate stronger psychometric properties for DISBA.

Similar content being viewed by others

Background

Adolescence is considered one of the major periods in structuring and establishing the personality [1]. Further, it is a crucial time in which mental and behavioral disorders may manifest [2, 3]. Early diagnosis and timely intervention of adolescents with mental and behavioral disorders is very important [4], and since 1950 many studies have been carried out on the prevalence of behavior disorders and problems among student adolescents [5, 6]. It is likely that the behavior problems which arise in this period appear later on in life as stable characteristics; therefore, detection of such behavior among students, and dealing with them correctly is essential [7].

In particular, disruptive behavior disorders (DBDs), including conduct disorder (CD), oppositional defiant disorder (ODD) and attention deficit hyperactivity disorder (ADHD), may manifest in children and adolescents and can be associated with a host of school difficulties and problems in later life. Common symptoms occurring in individuals with CD and ODD include: defiance of authority figures, angry outbursts, and other antisocial behaviors such as lying and stealing. It is felt that the difference between oppositional defiant disorder and conduct disorder is in the severity of symptoms and that they may lie on a continuum often with a developmental progression from ODD to CD with increasing age [8]. Furthermore, ODD often includes problems of emotional dysregulation (i.e., angry and irritable mood) not included in definitions of CD (American Psychiatric Asso., 2013) [9].

Today, there is little doubt regarding the emergence of disruptive behavior in adolescence. According to surveys, two to six percent of adolescents from typical demographics of society have some level of disruptive behavior [10]. This behavior has caused concern for families, schools, and public health, constituting the most common reason for adolescents to visit psychiatric clinics [7]. Students with disruptive behavior are faced with educational problems such as academic failure, expulsion, dropping out, and low grades, as well as high-risk behavior such as drug and alcohol abuse, and high-risk sexual behavior [11].

Students with disruptive behavior interrupt the learning process for other students, and the teacher’s ability to teach effectively; they also divert school resources and energy away from the main academic goals [12]. Adolescents with disruptive behavior have problems with their ability to understand and manage emotions [13] and higher risk of committing anti-social and criminal behavior [14]. Disruptive behavior is behavior which truly disrupts the learning and teaching processes in classroom or any other educational environment [15,16,17].

The cause of DBDs is not known. DBDs are more common among children aged 12 years and older; and child abuse or neglect and a traumatic life experience have been stated as risks for DBDs [18]. Additionally, It has been documented some socio-psychological and cultural factors may contribute to disruptive behavior [19]. For example, parent–child and school-child relationships may enhance the risk of developing DBD [20]; it has also been shown that life satisfaction and hope are negatively related to adolescent problem behaviour [21]. Disruptive behavior disorders are associated with psychological problems including anxiety, depression [22] and development of antisocial personality disorder later in life [19]. Psychosocial interventions that include parents, children, families and teachers, as well as behavioral support, can improve this disorder among adolescent [23].

DBD’s are related to poor outcomes for youth including involvement in crime and numerous educational problems [16, 17]; therefore, timely screening, detection and management of DBDs are of critical importance [24]. A number of rating scales exist to assist in detecting DBDs including the Conner’s Parent Rating Scale (CPRS), the disruptive behavior rating scale (DBRS), and the disruptive behavior scale-professed by students (DBS-PS). The CPRS focuses mainly on ADHD [8]; the DBRS consists of 45 questions, and has been validated among young children [25]; and the DBS-PS has only been validated among Portuguese students [15]. It is advantageous to develop screening that encompasses DBDs more generally, is brief, and is of relevance to older children. Furthermore, expanding validation of such screening tools to cultures other than Western cultures is important.

Because DBDs are association with important and potentially life-long impairment, and because DBDs are associated with significant societal costs, the current study aimed to design a suitable scale for screening DBDs. We therefore, designed a 29-item disruptive behavior screening scale among Iranian high school students and analyzed its psychometric properties.

Methods

The research population consisted of all the high school students aged fifteen to eighteen of Saveh city in the academic year 2015–2016. The sample size was determined four hundred people, considering the number of items in the scale (initially, 39 items) and following Munro [26] who recommended ten people for each item. To increase the accuracy of the study, six hundred students (300 girls and 300 boys) were selected for the study.

Sampling

A multi stage sampling was applied. Firstly, Saveh-a city located in the center of Iran, was divided into two parts: north and south. Among all high schools located in each region, four high schools (2 girls high schools and 2 boys high schools) were randomly selected from each district, which constituted a total of eight high schools. Then, among all students attending a high school, a random sample was selected using random numbers. It is worth mentioning that the required sample ratio for participation in the study was determined for each high school according to the number of students in each high school. In the last stage, the ratio of samples participating in the study from each class was determined for each of first and fourth grades according to the number of students in each grade.

The students were 15 to 18 years old and were the tenth, eleventh and twelfth grade students.

The students answered the anonymous scale without the presence of teachers, and without any compulsion, in a self-administered manner.

The scale

A student’s disruptive behavior scale was developed for this study. The disruptive behavior scale for adolescents (DISBA) was designed in reference to literature review and semi-structured interviews with students and high school authorities. Disruptive behavior in this study was considered as any type of behavior, which truly disrupts the learning and teaching processes in classroom or educational environment.

To develop the item-pool, we considered previous scales on disruptive behavior and conducted semi-structured interviews. The initial item pool consisted of 39 items, including the 16-item DBS-PS [15] along with 23 items derived from literature review [8, 24, 25] and interviews.

To develop the 23 items, focus groups were conducted with thirty students who were similar to the target population in terms of demographic properties, as well as with ten teachers and school staff Focus group data were analyzed for thematic content and then a panel of experts developed 23 items based on focus group themes and the literature. Finally, the research team then decided to utilize a 4-point Likert scale response option consisting of never (0), rarely (1), usually (2) and always (3) for each item.

Statistical analysis

Face validity

Both qualitative and quantitative methods were used to determine face validity. For quantitative face validity, 20 students were asked about the importance of each item in helping to identify disruptive classroom behavior. For the qualitative approach, students were asked to assess each item for ambiguity and difficulty. Overall, no problems in reading or understanding the items were expressed by the students. The quantitative face validity was evaluated through item impact score. Participants were asked to rate the importance of each item on a five-point Likert type scale form strongly important to not at all important. The scores ranged from 1 to 5 for each item. The item impact score for each item was calculated by multiplying the mean score of importance of an item with its frequency by relative frequency (percentage). The item impact scores of greater than 1.5 were considered suitable.

Content validity

A panel of experts (15 specialists in health education, psychiatry, health psychology, and educational psychology) rated items according to relevance. Each item was rated according to the following: (1) irrelevant, (2) important, but not essential, (3) essential. For each item a Content Validity Ratio (CVR) was computed as (ne − N/2)/(N/2), where ne is the number of experts rating the item as essential and N is the number of experts. The overall CVR index of the scale is computed as a mean of the items’ CVR values. The Content Validity Index (CVI) was also calculated Experts rated items on a four-point rating scale: (1) not relevant, (2) somewhat relevant, (3) quite relevant, and (4) very relevant. CVI is the percentage of experts rating an item as quite or very relevant. The recommended value for CVR is 0.59, for CVR scale index it is determined using Lawshe’s table, and for CVI the minimum recommended value is 0.79 [27, 28].

Construct validity

Exploratory factor analysis (EFA) was carried out to identify the underlying relationships between items. To determine the adequacy of the sample size, a Kaiser–Meyer–Olkin test was applied. A threshold of > 0.5 for corrected item–total–correlation was chosen as sufficient. SPSS 15 (SPSS, Inc., Chicago, IL, USA) was utilized for analyses, and items with factor loadings over 0.50 were retained. Confirmatory Factor Analysis (CFA) was carried out to test whether the data fit the hypothesized measurement model. The following cut-offs were considered appropriate [29]: 0.90 for the Comparative Fit Index (CFI), Goodness of Fit Index (GFI) and Normed Fit Index (NFI), 0.08 for the root mean square error approximation (RMSEA). Lisrel 8.8 (Scientific Software International, Inc., 2007) was used in this study for confirmatory factor analysis.

Reliability

Two methods were used to assess reliability: internal consistency and stability as described below:

-

1.

Internal consistency: this was assessed using Cronbach’s alpha coefficient. The value of 0.7 or above was considered satisfactory [30].

-

2.

Test–retest analysis. N = 25 students from the study sample completed the scale twice with an interval of 2 weeks. The intraclass correlation coefficient (ICC) was calculated and a value of 0.4 or above was considered acceptable [30, 31].

Ethics statement

The study was approved by the Ethics Committee of Saveh University of Medical Sciences. All the participants had signed the informed written consent form, where the confidentiality of the information received and the anonymity of responses to the scales was stressed.

Results

The average age and its standard deviation was 16.83 ± 0.86 for the male students and 16.62 ± 0.85 for the female students. The grade point average (GPA) of students was 15.8 ± 2.3 in the year before, on a scale from 12 to 20, where 20 indicates better performance. One hundred fifty-nine students (26.5%) had a history of smoking cigarettes or hookah within the 7 days before completing the study. One hundred fifty-three students (25.5%) were not happy with their lives.

Seven questions were omitted through examination of CVR, while three questions were omitted through examination of CVI. Twenty-nine out of thirty-nine questions, which had proper content validity, entered the stage of construct validity assessment using exploratory factor analysis. The Kaiser–Meyer–Olkin test for sampling adequacy and Bartlett’s sphericity test both indicated the data were suitable for EFA.

In the next stage, the Exploratory Factor Analysis found four factors with Eigen values greater than one: (1) aggressive school behavior, (twelve questions), (2) classroom defiant behavior (six questions), (3) unimportance of school, (six questions), and (4) defiance to school authorities (five questions). The factor loading matrix in Table 1 shows that all the extracted factor loadings are greater than 0.50, and these factors explain a total of fifty-nine percent of the cumulative variance.

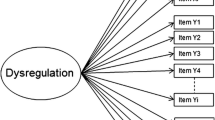

Confirmatory factor analysis was carried out to assess the results from the Exploratory Factor Analysis. The results showed that the structural model provided a good fit to the data. The Chi square value was significant χ2 = 17.16, df = 7.4, p = 0.02). The Goodness-of-Fit Index was 0.91, the adjusted goodness-of-fit index was 0.90, the Normed Fit Index was 0.92, the Comparative Fit Index was 0.96, and the root mean square error of approximation as 0.05. These figures indicate that the four-factor model of disruptive behavior has satisfactory goodness-of-fit (Table 2).

The reliability of the scale was assessed in terms of internal consistency and temporal stability. The Cronbach’s alpha coefficient ranged from 0.77 to 0.91, ICC’s ranged from 0.71 to 0.88 indicating satisfactory stability (Table 3).

Discussion

It is critical to detect students who may have disruptive behavior disorder, given that such behavior may lead to high-risk behavior such as delinquency, violence, drug abuse and anti-social personality if left untreated [28, 30]. This study presents a brief, valid and reliable scale with sub-parts that may aid in screening for DBDs in youth. Furthermore, many such scales are primarily created and validated in Westernized cultures, and it is important to expand validation and use in other countries.

To study construct validity, factor analysis was used and showed a 4-factor construct that explained 59% of variance, which is consistent with other similar studies [32]. Results of confirmatory factor analysis show that the data with the four presented constructs have sufficient goodness-of-fit.

The four-factor structure is not consistent with results obtained for the DBS-PS which yielded a three-factor structure consisting of distraction-transgression, schoolmate aggression and aggression to school authorities [15]. The four-factor structure found in this study included (1) aggressive school behavior, (2) classroom defiant behavior, (3) unimportance of School, and (4) defiance to school authorities. One possible explanation for such a difference at factor-level may be due to the fact that these scales have different number of items and have been validated among different populations with different age ranges and cultural backgrounds.

Based on DSM-5 disruptive behavior and ADHD are two distinct disorders although they may present similarly and may be co-exist. Behavior of children with ADHD may be disruptive, but this behavior by itself does not violate social norms or others’ rights and so does not usually meet criteria for CD [9]. As such, there are similarities between DISBA and scales that screen for ADHD symptoms including: losing things, making mistakes, arguing, damaging things or equipment, failing to do tasks, having problem with relationship and skipping schools. While screening can alert professionals to a potential behavioral problem, further assessment and diagnosis will help in determining how to target and tailor interventions for specific disorders.

The results of the study show that the students’ disruptive behavior scale has good internal consistency ranging from 0.77 to 0.91. This is consistent with a similar study on Portuguese students that also showed the reliability ranged from 0.67 to 0.88 [15]. Test–retest results indicate a high degree of reliability in the DISBA, which is again consistent with the aforementioned study on Portuguese students that found test–retest reliability to be 0.85 [15].

Limitation

Future studies may wish to examine the correlations between scales and other phenomena associated with DBD, such as observations of stealing, fighting, etc. In addition, future studies may wish to examine how well scales distinguish between youth with and without a diagnosis of DBD (ODD, CD, or ADHD), and sensitivity to detect change in behavior over time (e.g., following intervention).

Conclusion

According to the results of this study, this brief 29-item scale evidences good validity and reliability. School authorities and teachers might use DISBA to screen students in order to identify problematic students in need of further evaluation for diagnosis and intervention. Although based in part on the DBS-PS, the DISBA evidences good psychometrics in a non-Westernized culture, allows for screening based on four relevant scales for the school setting as compared to only three, and can be used with youth ages 15–18 years old.

Abbreviations

- CVR:

-

content validity ratio

- CVI:

-

Content Validity Index

- CFA:

-

confirmatory factor analysis

- RMSEA:

-

root mean square error of approximation

- NFI:

-

Normed Fit Index

- GFI:

-

Goodness of Fit Index

- CFI:

-

Comparative Fit Index

References

Karimy M, Niknami S, Heidarnia AR, Hajizadeh I, Montazeri A. Prevalence and determinants of male adolescents’ smoking in Iran: an explanation based on the theory of planned behavior. Iran Red Crescent Med J. 2013;15(3):187–93.

Stringaris A, Maughan B, Copeland WS, Costello EJ, Angold A. Irritable mood as a symptom of depression in youth: prevalence, developmental, and clinical correlates in the Great Smoky Mountains Study. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 2013;52:831–40.

Dray J, Bowman J, Freund M, Campbell E, Hodder RK, Lecathelinais C, Wiggers J. Mental health problems in a regional population of Australian adolescents: association with socio-demographic characteristics. Child Adolesc Psychiatry Ment Health. 2016;10(1):32.

Undheim AM, Lydersen S, Kayed NS. Do school teachers and primary contacts in residential youth care institutions recognize mental health problems in adolescents? Child Adolesc Psychiatry Ment Health. 2016;10(1):19.

Manninen M, Pankakoski M, Gissler M, Suvisaari J. Adolescents in a residential school for behavior disorders have an elevated mortality risk in young adulthood. Child Adolesc Psychiatry Ment Health. 2015;9(1):46.

Buchanan T. Internet-based questionnaire assessment: appropriate use in clinical contexts. Cogn Behav Ther. 2003;32:100–9.

Moreland AD, Dumas JE. Categorical and dimensional approaches to the measurement of disruptive behavior in the preschool years: a meta-analysis. Clin Psychol Rev. 2008;28(6):1059–70.

Sadock BJ, Sadock VA. Kaplan and Sadock’s synopsis of psychiatry. Behavioral sciences/clinical psychiatry. Philadelphia, US: Lippincott Williams and Wilkins and Wolter Kluwer Health; 2011.

Association AP. Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders (DSM-5®). USA: American Psychiatric Pub; 2013.

Semke CA, Garbacz SA, Kwon K, Sheridan SM, Woods KE. Family involvement for children with disruptive behaviors: the role of parenting stress and motivational beliefs. J Sch Psychol. 2010;48(4):293–312.

Nock MK, Kazdin AE, Hiripi E, Kessler R. Prevalence, subtypes, and correlates of DSM-IV conduct disorder in the National Comorbidity Survey Replication. Psychol Med. 2006;36:699–710.

Amada G, Smith MC. Coping with misconduct in the college classroom: a practical model. Asheville: College Administration Publications; 1999.

Ciarrochi J, Chan AY, Bajgar J. Measuring emotional intelligence in adolescents. Personal Individ Differ. 2001;31(7):1105–19.

Motamedi M, Amini Z, Siavash M, Attari A, Shakibaei F, Azhar MM, Harandi RJ, Hassanzadeh A. Effects of parent training on salivary cortisol in children and adolescents with disruptive behavior disorder. J Res Med Sci. 2008;13(2):69–74.

Veiga F. Disruptive behavior scale professed by students (DBS-PS): development and validation. Int J Psychol Psychol Ther. 2008;8:203–16.

Lannie AL, McCurdy BL. Preventing disruptive behavior in the urban classroom: effects of the good behavior game on student and teacher behavior. Educ Treat Child. 2007;30(1):85–98.

Walker HM, Ramsey E, Gresham FM. Heading off disruptive behavior: how early intervention can reduce defiant behavior—and win back teaching time. Am Educ. 2003;26(4):6–45.

John M. Eisenberg Center for Clinical Decisions and Communications Science, AHRQ Comparative Effectiveness Reviews Treating Disruptive Behavior Disorders in Children and Teens. A review of the research for parents and caregivers, in comparative effectiveness review summary guides for consumers. Rockville: Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality; 2005.

Rijlaarsdam J, Tiemeier H, Ringoot AP, Ivanova MY, Jaddoe VWV, Verhulst FC, Roza SJ. Early family regularity protects against later disruptive behavior. Eur Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 2016;25(7):781–9.

Johnston C, Mash EJ. Families of children with attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder: review and recommendations for future research. Clin Child Fam Psychol Rev. 2001;4(3):183–207.

Salami SO. Moderating effects of resilience, self-esteem and social support on adolescents’ reactions to violence. Asian Soc Sci. 2010;6(1):101.

Butler AM, Titus C. Systematic review of engagement in culturally adapted parent training for disruptive behavior. J Early Interv. 2015;37(4):300–18.

Wolf NJ, Hopko DR. Psychosocial and pharmacological interventions for depressed adults in primary care: a critical review. Clin Psychol Rev. 2008;28(1):131–61.

Masi G, Milone A, Brovedani P, Pisano S, Muratori P. Psychiatric evaluation of youths with disruptive behavior disorders and psychopathic traits: a critical review of assessment measures. Neurosci Biobehav Rev. 2016. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.neubiorev.2016.09.023.

Friedman-Weieneth JL, Doctoroff GL, Harvey EA, Goldstein LH. The disruptive behavior rating scale—parent version (DBRS-PV) factor analytic structure and validity among young preschool children. J Atten Disord. 2009;13(1):42–55.

Munro BH. Statistical methods for health care research. 1st ed. Philadelphia: Lippincott Williams & Wilkins; 2005.

Lawshe CH. A quantitative approach to content validity. Pers Psychol. 1975;28(4):563–75.

Waltz C, Bausell BR. Nursing research: design statistics and computer analysis. Philadelphia: Davis FA; 1981.

Hu LT, Bentler PM. Cut-off criteria for fit indexes in covariance structure analysis: conventional criteria versus new alternatives. Struct Equ Model. 1999;6:1–55.

Patterson P. Reliability, validity, and methodological response to the assessment of physical activity via self-report. Res Q Exerc Sport. 2000;71(sup2):15–20.

Polit DF, Beck CT. The content validity index: are you sure you know what’s being reported? Critique and recommendations. Res Nurs Health. 2006;29(5):489–97.

Zuddas A, Marzocchi GM, Oosterlaan J, Cavolina P, Ancilletta B, Sergeant J. Factor structure and cultural factors of disruptive behaviour disorders symptoms in Italian children. Eur Psychiatry. 2006;21(6):410–8.

Authors’ contributions

All author contributed in design, data gathering and analysis. All authors contributed to drafting the manuscript. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Acknowledgements

The number S556 is associated with this research project. Financial support associated with this project and its home institution is recognized and appreciated. We sincerely acknowledge our gratitude to the Chairman of Saveh Education Office, the teachers and participating students in this study and all those who helped us to conduct this study. We are grateful to Professor Ali Montazeri for his valuable comments on the earlier version of the manuscript.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Availability of data and materials

Upon request, we can offer external researchers onsite-access to the data analyzed at Saveh University of Medical Sciences, Ahvaz, Iran.

Consent for publication

Consent for publication is included in the consent to participate in research. Students’ parents signed informed consent for participation and consent for publication.

Ethics approval and consent to participate

All participants were informed about study confidentiality. Informed consent was obtained from all the participants and their parents; the study was approved by the ethics committee of Saveh University of Medical Sciences. The research ensures the protection of data, both during and after the completion of the research work.

Funding

Financial support was received from Saveh University of Medical Sciences.

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made. The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver (http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/) applies to the data made available in this article, unless otherwise stated.

About this article

Cite this article

Karimy, M., Fakhri, A., Vali, E. et al. Disruptive behavior scale for adolescents (DISBA): development and psychometric properties. Child Adolesc Psychiatry Ment Health 12, 17 (2018). https://doi.org/10.1186/s13034-018-0221-8

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s13034-018-0221-8