Abstract

Background

Typically, specialist mental health professionals deliver psychological interventions for individuals with poorly controlled type 2 diabetes mellitus (T2DM) and related mental health problems. However, such interventions are not generalizable to low- and middle-income countries, due to the dearth of trained mental health professionals. Individuals with little or no experience in the field of mental health (referred to as non-specialists) may have an important role to play in bridging this treatment gap.

Aim

To synthesise evidence for the effectiveness of non-specialist delivered psychological interventions on glycaemic control and mental health problems in people with T2DM.

Methods

Eight databases and reference lists of previous reviews were systematically searched for randomized controlled trials (RCTs). Outcome measures were glycated hemoglobin (HbA1c), diabetes distress and depression. The Cochrane Collaboration Risk of Bias Tool was used for risk of bias assessment. Data from the included studies were synthesized using narrative synthesis and random effects meta-analysis.

Results

16 RCTs were eligible for inclusion in the systematic review. The 11 studies that were pooled in the meta-analysis demonstrated a reduction in HbA1c in favor of non-specialist delivered psychological interventions when compared with control groups (pooled mean difference = − 0.13; 95% CI − 0.22 to − 0.04, p = 0.005) with high heterogeneity across studies (I2 = 71%, p = 0.0002). The beneficial effects of the interventions on diabetes distress and depression were not consistent across the different trials.

Conclusion

Non-specialist delivered psychological interventions may be effective in improving HbA1c. These interventions have some promising benefits on diabetes distress and depression, although the findings are inconclusive. More studies of non-specialist delivered psychological interventions are needed in low- and middle-income countries to provide more evidence of the potential effectiveness of these interventions for individuals living with T2DM.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Background

Type 2 diabetes mellitus (T2DM) is a prevalent and progressive chronic illness, with 463 million people worldwide estimated to be living with this condition and a projected increase to 700 million by 2045 [1]. Most individuals living with T2DM experience different negative emotions and maladaptive behaviours that affects their effort to adjust to the self-management regimen required to maintain optimal glycaemic levels [2]. In recent times, the mental state of individuals living with T2DM has received attention with Lin et al. [2] highlighting the prevalence of depression, diabetes distress (subclinical emotional distress) and anxiety among these individuals. In addition, Fisher et al. [3] and Nefs et al. [4] found that symptoms of depression and diabetes distress persist over time, and for at least 12 months after diabetes diagnosis. Research suggests that there is a bidirectional association in the form of shared biological mechanisms and burden of the condition [5, 6].

Individuals with T2DM experience depression at a rate twice that of the general population [7, 8]. Diabetes distress (defined as the negative feelings, moods and attitudes that individuals living with diabetes experience as they live with, and manage diabetes on a daily basis) a higher prevalence than depression across different settings, ranging from 18 to 64%. [9, 10] In North American and European studies, co-occurring symptoms of diabetes distress and depression in people with diabetes are associated with functional impairment, onset of diabetes-related complications, early mortality, poor adherence to dietary regimen and hyperglycemia [11,12,13,14]. Similar findings have been reported in studies in sub-Saharan Africa [15,16,17], where the co-occurrence of these mental health problems alongside T2DM is associated with reduced quality of life, poor medication adherence, increased healthcare costs and low financial status in individuals.

With increasing numbers of people living with T2DM globally, interventions are needed to simultaneously address mental health problems and improve key diabetes-related outcomes (glycaemic control) in individuals with T2DM. Previous systematic reviews and meta-analyses [18,19,20,21], showed that psychological interventions namely cognitive behavior therapy (CBT), client centered therapy (CCT), problem solving therapy (PST), motivational interviewing (MI) and mindfulness, were more effective than usual care in reducing depression and diabetes distress and improving glycaemic control in people with T2DM, with effect sizes ranging from medium to large. Chew et al. [22] and Winkley et al. [23] found a small effect of psychological interventions on HbA1c, with both reviews reporting effect sizes of 0.14 and 0.19 respectively. The small effects on HbA1c in these reviews may be explained by improving standards of usual care for diabetic patients seen in studies conducted in high income settings as well as the good glycaemic control of participants in majority of these studies.

Despite suggestions that psychological interventions can be beneficial in the management of diabetes, with much of the available evidence coming from high income countries and while, there is the likelihood of positive and consistent effects in low- and middle-income countries especially sub-Saharan Africa, this approach cannot be applied in these settings due to shortage of trained mental health professionals. To put that into context, it is estimated that on average, there are 44.8 mental health professionals per 100,000 population in European countries compared with 1.6 per 100,000 population in sub-Saharan African countries [24]. However, there is growing evidence [25,26,27] that non-specialist such as health professionals (e.g. physicians) and non-health professionals (e.g. university graduates and community health workers) could play important roles in bridging this treatment gap as they have been involved in the detection and treatment of mental health problems. Systematic reviews to evaluate the effects of psychological interventions on glycaemic control and mental health included but did not distinguish between studies which have looked at both specialists and non-specialists delivering the intervention [18, 21, 22]. This makes it difficult to estimate the effectiveness of using non-specialists to deliver psychological interventions for individuals with T2DM. Hence, a review is necessary to synthesise evidence for non-specialist delivered psychologically-informed interventions on the mental health and glycaemic control of individuals with T2DM. Although interventions delivered by non-specialists are likely to be more common in (and relevant to) low- and middle-income settings, studies were not excluded on the basis of setting.

Objectives

This review was conducted to establish whether psychological interventions delivered by non-specialists (defined as individuals without specialised professional training in the field of mental health) are effective in improving glycaemic control and alleviating mental health problems (depression and diabetes distress), with the secondary aim of identifying which components of these interventions were likely to be important in achieving these outcomes.

Methods

Protocol and registration

The protocol of this review is available from PROSPERO database (Registration ID: CRD42020176738). This review was reported in line with the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA) guidelines [28].

Eligibility criteria

Eligibility criteria included randomised controlled trials (RCTs) of non-specialist delivered psychological interventions for individuals (18 years and above) with a clinical diagnosis of type 2 diabetes.

Interventions were classified as psychological if they met the following criteria: (i) at least one part of the intervention was guided by established psychological principles and techniques; (ii) it involved interpersonal interaction between therapist and patient, such that the patient plays an active role in the intervention; (iii) intervention was aimed, either exclusively or in part at improving mental health outcomes. Examples of established psychological therapies are cognitive behavioural therapy (CBT), behaviour therapy, mindfulness and problem-solving therapy (PST). For interventions not explicitly described as psychological, authors were contacted for further information. Studies involving combined or collaborative methods of treatment were included (eg CBT or behaviour therapy combined with diabetes education).

‘Non-specialist’ providers were defined as individuals who have not received intensive professional specialist training in the field of mental health. These included health and social care professionals (doctors, nurses and other allied health professionals). This category also included individuals who have undergone some training in the field of mental health such as undergraduate modules or brief introductory courses in mental health. Non-health professionals such as community health workers, peers, students were considered for inclusion as non-specialist providers as they are involved at the community level and have a significant role to play especially in the detection and treatment of mental health problems as well as improving access to mental health care [29, 30]. Non-specialist providers do not include mental health professionals such as psychiatrists, psychologists, psychiatric nurses and social workers. Comparators (control conditions) were usual care, waitlist and diabetes education. Co-primary outcomes were glycaemic control (change in HbA1c) and depression and/or diabetes distress as measured using validated tools. With regards to depression, diagnostic and symptom severity tools were considered appropriate for inclusion. Studies in which diabetes distress was the mental health outcome were included where this was measured by either Problem Areas in Diabetes scale (PAID-5 or PAID-20) or Diabetes Distress Scale (DDS-17). Non-English articles were omitted based on the linguistic ability of the author.

Information sources

The following databases were searched in retrieving studies: Ovid PsycINFO, Ovid MEDLINE, Ovid EMBASE, Ovid CINAHL, Cochrane Central Register of Controlled Trials. Websites such as www.clincialtrials.gov, www.globalhealthlibrary.net, and www.who.int/trialsearch were searched for trials that have been completed and their results, as well as reference lists of similar reviews.

Search strategy

The ‘non-specialist’ search strategies from a review of mental health treatments delivered by non-specialist health workers [31] were used in this review. In addition to this, a combination of keywords, wildcards and relevant truncation related to type 2 diabetes mellitus, depression and diabetes distress was used. Ongoing trials were excluded from this review. There was no limitation on year of publication. A preliminary search was conducted on 19 September 2019 and the final search was conducted on 5 August 2020. The search strategies are shown in Appendix 1.

Study selection

Reference management software (Mendeley) was used to compile results from the databases and exclude duplicate references. After screening titles and abstracts of retrieved studies, full text of potentially eligible studies was examined for inclusion, with exclusion reasons recorded. Titles and abstracts of retrieved studies were initially screened against the eligibility criteria by the primary author (AO). The second author (IU) independently reviewed a random 10% percent of title, abstracts and full text studies to ensure that there is no incorrect exclusion of relevant studies [32]. In the selection process, consensus was reached through discussion. In the event that consensus was not reached, one of the additional reviewers (SW,RB) was called upon to make the final decision.

Data extraction

The lead author (AO) used a standardized data collection form (based on Cochrane collaboration data collection form for RCTs) to extract necessary information from included studies, piloted tested it on five randomly-selected included studies with the second author (IU) and refined it accordingly. Data was extracted from each included trial on study design, country, mean age of participants, sample size, duration of T2DM, cadre/choice/title of non-specialist, intervention characteristics and outcomes. Authors of included studies were contacted for missing data.

Risk of bias and quality assessment

The Cochrane Collaboration Risk of Bias Tool was used to ascertain risk of bias in included studies [33]. The lead author assessed the included studies using the risk of bias tool and a random 10% of the included studies was extracted and assessed independently by the second author (IU). Consensus was reached through discussion. In the event that consensus was not reached, one of the additional reviewers (SW, RB) was called upon to make the final decision. The Grading of Recommendations, Assessment, Development and Evaluations (GRADE) approach was used to assess the quality of evidence for each outcome, which takes into account issues related to internal validity (risk of bias, inconsistency, imprecision, publication bias) and external validity (directness of results). Certainty in the evidence from included studies was rated down from ‘high quality’ by one level for serious (or by two for very serious) study limitations as specified in the GRADE domains (Appendix 3).

Data synthesis

Data from included studies were pooled in meta-analysis and synthesized using the Review Manager (v5.3). Where statistical pooling was not possible, findings were analysed narratively. Significant diversity was expected in the included studies and as such, random-effects meta-analysis was performed, and assessment of heterogeneity was by chi-squared and Higgins’ I2 test. In the event that there were adequate number of studies, subgroup analyses by category of non-specialist providers (health professionals and non-health professionals) and intervention characteristics were carried out to check if the intervention effect varied. Risk of publication bias was determined based on visual inspection of a funnel plot. Effect sizes were calculated as standardized mean difference (SMD) for continuous outcome variables and were classified as small effect (0.2), medium effect (0.4) and large effect (0.8) [34].

Results

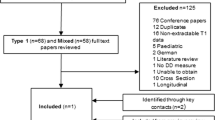

Initial electronic searches generated 2367 results before elimination of duplicates, with 106 additional references identified through reference lists of systematic reviews and meta-analyses. 1613 studies were excluded after title and abstract screening. There was 81% agreement in identifying abstracts for full retrieval (Cohen’s kappa = 0.81). Disagreements were discussed and when it was not possible to meet consensus, one of the additional reviewers was consulted. 248 full text studies were reviewed., with 16 studies included in the final review (Fig. 1).

Study characteristics

The 16 included studies were all conducted in high income countries: Germany (n = 1), Netherlands (n = 3), Taiwan (n = 1), UK (n = 2) and USA (n = 9). The characteristics of the studies are summarised in Table 1. Two authors responded to requests for additional information. In total, 4863 participants were involved in the studies in this review and sample sizes ranged from 53 to 1299 participants. A total of eleven RCTs (n = 1940) were included in the meta-analysis and sample sizes ranged from 53 to 545 participants. Twelve studies [35, 37, 39,40,41,42,43,44, 46, 47, 49, 50] had a two-arm design; two [36, 38] had a three-arm design; two [45, 48] had a four-arm design. Mean age of participants was between 50 to 70.7 years and mean duration of diabetes was between 2.7 ± 3.0 and 10.5 ± 8.3 years. One study [36] did not report mean age of participants. Four trials [36, 39, 41, 47] did not report mean duration of diabetes. There were more female than male participants in 8 studies, [38, 39, 41, 43, 44, 46,47,48] with one study [50] focusing on only females.

Intervention characteristics

The intervention differed with regards to the type of non-specialists used, and in the nature of psychological intervention, duration and number of sessions. Among the included studies, psychological interventions were delivered by nurses [39, 40, 43, 50]; dietitians [37]; college graduates [38]; research assistants [35, 41]; undergraduate students [44]; peers i.e. diabetic patients [45] and community health workers [46, 47]. Welschen et al. [49] used dietitians and diabetes nurses to deliver the psychological intervention. Welch et al. [48] used diabetes educators. Interventionists in Dale et al. [36] were diabetes patients and diabetes nurses. Kim et al. [42] used nurses and community health workers to deliver their intervention. Most interventionists were health professionals (n = 7) or non-health professionals (n = 7).

Psychological treatments used in the interventions were cognitive behaviour therapy, motivational interviewing, problem solving therapy and mindfulness. Thirteen trials employed single psychological treatments in their interventions [35,36,37,38,39,40,41, 43,44,45,46, 48,49,50]. Three studies [37, 42, 47] incorporated two psychological treatments in their interventions. The frequency of intervention sessions ranged between 2 and 12 sessions, and duration of sessions ranged between 15 min and 2 h, over a period of 6 weeks to 24 months. Duration of intervention sessions was not reported for Dobler et al. [37] and Welschen et al. [49]. Gabbay et al. [39] did not report the frequency of sessions. Eight studies used individual intervention sessions [35,36,37, 39, 42, 44, 49, 50] and four studies used group sessions [41, 42, 46, 47]. Simmons et al. [45] used both individual and group intervention sessions. Three studies [38, 40, 48] did not specify the format of the intervention sessions. 14 studies reported the training of non-specialists by expert professionals. Two studies [42, 50] did not report the training of the non-specialist. In the control group, there were ten, four and two studies administering usual care, diabetes education and waiting list respectively.

Outcomes

Five studies examined diabetes distress only, four studies examined depression only, seven studies measured both diabetes distress and depression and all 16 examined glycemic control. Diabetes distress was measured using DDS-17 in two studies [38, 45]; PAID-5 in one study [47] and PAID-20 in nine studies [35,36,37, 39, 40, 43, 46, 48, 50]. Depression was assessed using CES-D in five studies [35, 39, 41, 47, 49]; PHQ-8 in two studies [45, 47] and PHQ-9 in four studies [37, 42, 44, 46].

Effect of non-specialist delivered psychological intervention on HbA1c

Eleven out of 16 RCTs included in the systematic review supplied sufficient data for meta-analysis. The meta-analysis produced an estimated effect size of − 0.13 for those randomised to a non-specialist delivered psychological intervention compared with the control group (95% CI − 0.22 to − 0.04, Z = 2.84, p = 0.005). There was high heterogeneity across the studies included in the meta-analysis (I2 = 71%, p = 0.0002). Excluding studies with multiple intervention arms (Dale et al. [36]; Welch et al. [48]) resulted in an increase in pooled HbA1c effect size from − 0.13 to − 0.24 (95% CI − 0.34 to − 0.14, p < 0.00001, I = 39%).

There were not enough studies to pool the effect sizes of different sub-categories of health professionals and non-health professionals. Comparison for different intervention providers indicated that non-health professionals delivered interventions seemed to have more favorable results than health professionals delivered interventions (SMD = − 0.24 95% CI − 0.47 to − 0.00, p = 0.05). Health professionals combined with non-health professionals showed an effect size of − 0.21 (95% CI − 0.40 to − 0.02, p = 0.03). Non-specialist delivered CBT interventions produced a non-significant effect of − 0.16 in HbA1c (95% CI − 0.41 to 0.09, p = 0.21). CBT combined with another psychological treatment had an effect size of − 0.39 (95% CI − 0.61 to − 0.16, p = 0.0007). Non-specialist delivered MI interventions had a non-significant effect size of − 0.01 (95% CI − 0.11 to 0.13, p = 0.87). MI combined with another psychological treatment had an effect size of − 0.51 (95% CI − 0.70 to − 0.31, p < 0.00001). Longer non-specialist delivered interventions (6 sessions and more) seemed to reduce HbA1c better (SMD = − 0.28, CI − 0.39 to − 0.17, p < 0.0001) in comparison with the brief interventions (SMD = 0.15, CI − 0.00 to 0.30, p = 0.05) (Fig. 2). In studies with participants with suboptimal glycemic control (HbA1c above 7%), there was no difference in overall effect size (SMD = − 0.14, CI − 0.24 to − 0.05, p = 0.003).

Of the studies that could not be pooled in the meta-analysis, one trial [35] reported significant decline in HbA1c levels at 3-month and at 8-month follow-up in participants with HbA1c levels less than 8% who had received CBT treatment.

Effect of non-specialist delivered psychological intervention on diabetes distress

Given the varying measures used, results were not pooled in a meta-analysis. Of the twelve studies examining the impact on diabetes distress, four studies reported significant improvement in diabetes distress. Fisher et al. [38] reported that participants that received PST in addition to self-management education produced significantly greater reduction in diabetes distress relative to the other groups (p < 0.001; 392 participants). Even at 12-month follow-up this effect was sustained. In Spencer et al. [46] patients who received MI plus diabetes education significantly reduced diabetes distress compared to patients who received diabetes education alone (p < 0.05; 164 participants). Similarly, this was sustained at 6-month follow-up. In Whittemore et al. [50] 6 nurse-led sessions of MI plus self-management education resulted in significant decrease in diabetes distress (p < 0.01; 53 participants). The largest trial (n = 1299) by Simmons et al. [45] found that 8–12 peer-delivered individual sessions of MI tailored for T2DM patients were more effective than group sessions (− 0.42 95% CI − 0.75 to − 0.10). Conversely, in five interventions [36, 37, 39, 40, 48], there was no significant difference in diabetes distress score between the MI and control groups. Furthermore, studies [35, 43, 47] that used CBT either as single treatments or in conjunction with another psychological treatment did not significantly improve diabetes distress.

Effect of non-specialist delivered psychological intervention on depression

The results for depressive symptom scores were not pooled in a meta-analysis as a result of the different scales used in measuring depression. Seven studies out of eleven reported significant improvements in depression. Gabbay et al. [39] reported that 2–9 MI sessions delivered by nurses significantly reduced depressive symptoms compared to those in the usual care group (p = 0.02). Inouye et al. [41] found that CBT delivered over 6 sessions by research assistants were effective in significantly improving symptoms of depression (p = 0.03). However, this effect was not sustained at 12 months follow-up (p-0.09). Similarly, in Sacco et al. [44] 9 undergraduate students-delivered sessions utilizing CBT techniques was found to significantly improve symptoms of depression (p < 0.005) whereas in Kim et al. [42], depression score in the waitlist control group decreased more than that in the intervention group. Welschen et al. [49] reported that patients who received 3–6 dietitians and diabetes nurses CBT sessions had significantly reduced symptoms of depression (p = 0.01). This effect was not sustained at follow-up (0.70). Wagner et al. [47] showed that 8 community health worker-led sessions of integrated care intervention involving techniques of dual therapy of CBT and mindfulness as well as diabetes education were effective in reducing depressive symptoms (p = 0.002). In Dobler et al. [37] MI combined with PST significantly improved depression symptoms. Conversely, in studies [35, 45, 46, 48] that used single psychological treatments of either CBT or MI, there was no significant difference in depression symptom score between the intervention and control groups.

Risk of bias

Eight studies described a clear randomization process. Six studies did not provide enough information on the random sequence generation and were classified as unclear. Gabbay et al. [39] and Sacco et al. [44] were judged high risk of bias as they described a non-random component in the sequence generation process. Adequate concealment of allocations to intervention and control group was done in nine studies. Six studies reported insufficient information to permit judgement on this criterion. Sacco et al. [44] was judged high risk of bias as the method of allocation concealment could introduce bias.

Ten studies were assessed as high risk of performance and detection bias as the measurement of diabetes distress is likely to be influenced by lack of blinding. Chiu et al. [35] and Fisher et al. [38] were judged to report insufficient information on this criterion. Nine studies were assessed as high risk of performance and detection bias as the measurement of depression is likely to be influenced by lack of blinding. Chiu et al. [35] and Inouye et al. [41] were reported as having insufficient information on this criterion. Fifteen studies had low risk of performance and detection bias as measurement of HbA1c was not likely to be influenced by lack of blinding. Dobler et al. [37] yielded insufficient information to provide judgement on this criterion.

Eleven studies had low risk of reporting bias. Four studies were judged high risk of reporting bias. Heinrich et al. [40] had insufficient information to allow judgement on this criterion. Fourteen studies were judged to exhibit a low risk of attrition bias as the attrition in these studies did not affect outcomes, while Simmons et al. [45] and Wagner et al. [47] had attrition rates with possible impact on outcome data and were judged high risk.

Discussion

We investigated the effects of non-specialist delivered psychological interventions on glycaemic control and mental health outcomes in individuals with T2DM. Although CBT and MI were commonly used, this review included trials of other psychological interventions delivered by non-specialists such as PST and mindfulness. A core mechanism in CBT and PST is the disclosure and subsequent reframing of negative thoughts and beliefs to achieve positive outcomes. MI facilitates expression of the individual’s beliefs, conflicts and barriers with the aim of stimulating behaviour change and adaptive coping. Overall, the review provides promising results with regards to the effect of non-specialist delivered psychological interventions on glycaemic control, depression and diabetes distress.

Main findings

The 11 studies that were pooled in the meta-analysis demonstrated a reduction in mean HbA1c in favor of non-specialist delivered psychological interventions when compared with control groups and a significantly higher reduction was seen after trials with multiple intervention groups. Looking at the different types of non-specialist delivered psychological interventions, interventions that combined either CBT or MI with another psychological treatment showed the best improvement in HbA1c. Meta-analyses further showed that individuals living with T2DM might benefit more from non-specialist delivered psychological interventions with longer sessions with regard to the decrease of their HbA1c. The varying effect sizes highlighted in this review, from small to moderate, are likely to result in modest clinical improvements in glycemic control. These findings support the view of Chapman et al. [18] in using psychological interventions of CBT and MI for achieving clinically relevant benefits. The results from this review and Winkley et al. [23] are similar, in that, they report small effect in psychological interventions with participants with suboptimal glycemic control. There was a difference in the changes in glycaemic control when interventions were delivered by non-health professionals or health professionals combined with non-health professionals. This indicates that these types of interventions may hold possible benefits for persons living with T2DM in reducing the risk of onset and progression of T2DM related complications. However, the small number of studies warrant further research to know whether non-specialist delivered psychological interventions can sustain improvements in glycaemic control in individuals living with T2DM.

This review showed mixed results for diabetic distress in people with T2DM, with non-specialist delivered psychological interventions improving diabetes distress in some studies using college graduates, nurses, community health workers and diabetes peers, and reporting non-significant effect in others. With one exception [50], results from these four studies suggest that the improvements can be maintained over time, as Spencer et al. [44] and Fisher et al. [38] sustained the positive effects at 6-month and 12-month follow up respectively. The inconsistency of the effects of these interventions on diabetes distress could be the consequence of low intervention fidelity, insufficient intervention content addressing issues that are specific to living with diabetes and its management, personal perception of distress as well as mean diabetes distress score below cutoff point of the diabetes distress scales used. Although the results differ from the review by Schmidt et al. [51] who reported consistent effect of psychological interventions on diabetes distress, it should be noted that Schmidt et al. [51] reviewed studies that included individuals with type 1 and type 2 diabetes. Notably, the differential effect of non-specialist delivered psychological intervention was not observed in findings reported by Schmidt et al. [51] and thus, is a unique feature of this review.

There was more non-specialist delivered psychological interventions that had beneficial effects on depression than those achieved for diabetes distress. The improvement in depression symptoms were only observed in six studies that used students, research assistants, community health workers, dietitians and diabetes nurses. This differs from findings reported by Beres et al. [52] who found that six non-specialist delivered psychosocial interventions did not have any beneficial effect on depressive symptoms. It is noteworthy that the results of Beres et al. [52] are not consistent with the findings of this review as most of the interventions in Beres et al. [52] utilized psychoeducation rather than specific forms of psychological treatment such as CBT, MI or PST as was observed in this present review. The studies in this present review that reported improvements in depressive symptoms used CBT and this is congruent with other studies that reported the effects of CBT in treating depression in individuals with other chronic illnesses such as HIV/AIDS, stroke and chronic pain [53, 54]. Positive effects were sustained in Wagner et al. [47] at 3-month follow-up. However, these effects were not sustained at 6-month follow-up in Welschen et al. [49]; suggesting effectiveness of CBT in the short-term. It has been pointed out that depression is distinguished by persistent unhelpful thoughts that often results in feelings of guilt and low mood; hence the improved outcomes may be attributed to the role of CBT in identifying, disputing and changing unhelpful distortions (thoughts, feelings and behaviours).

In the studies under review, different non-specialists were used to deliver interventions. Unfortunately, important information related to non-specialists was often not reported including background, selection process and prior training. However, level of education was considered to be important in some studies, with attempts to recruit non-specialists with tertiary-level education such as research assistants, graduates and university students [35, 38, 41, 44]. Others sought to match non-specialists with the participants, for example on diabetes status; as peers or originating from the same community; community health workers [36, 45,46,47]. Likewise, other studies sought non-specialists that are directly involved in improving patient’s general health such as nurses and dietitians. [37, 39, 43, 48,49,50].

Furthermore, it was observed that the non-specialists with tertiary level education were trained in basic skills of CBT and PST, that are easy to learn and administer such as activity scheduling, behavioral experiments, reattribution and problem solving. Non-specialists directly involved in improving patient health underwent comprehensive training in MI and CBT including psychoeducation, with the shortest and longest duration of training being 2 days and 80 h respectively. Similarly, non-specialists selected on the basis of characteristics shared with participants also underwent comprehensive psychological treatment training (CBT, MI and mindfulness) including psychoeducation. Most studies explicitly stated that the training was conducted by specialist mental health professionals. Despite the variability in training duration, it has been suggested that training in psychological treatments has little influence on treatment effectiveness [55]. Wampold and Imel [56] acknowledged the importance of therapist characteristics such as empathy and adherence to intervention protocol in influencing treatment outcomes. The studies in this review did not explore any of these meaning that more attention needs to be paid to the attributes and qualities that make people adequate and appropriate non-specialist.

Comparison with previous findings

The findings of the review suggest that psychological interventions delivered by non-specialists and aimed at older individuals with longer sessions may improve poor glycaemic control and mental health. More intense interventions (6 or more sessions) and those of longer duration (9 weeks or longer) were found to contribute to improved HbA1c levels and mental health outcomes. Brief interventions are likely to result in short-lived beneficial effects as observed in Welschen et al. [49] and Inuoye et al. [41]. Although this finding agrees with Sturt et al. [57] who reported that psychological interventions with intense sessions (6 or more) and longer duration (13 weeks or longer) decreases diabetes distress and HbA1c levels, this was recommended for delivery by specialists such as psychologists and psychiatrists. Neither the format of intervention sessions (individual or group) nor mode of delivery (face to face, web-based, phone-based) were found to influence the effectiveness of non-specialist delivered psychological interventions in spite of their relative advantages.

Strength and limitations of this review

This review highlighted that all of the non-specialist delivered psychological interventions were conducted in high income countries even though they are needed in low- and middle-income countries, including sub-Saharan Africa, where specialist mental healthcare providers are scarce. The review identified an important age gap given that most of the participants in the included studies were over 50 years. This is concerning given that mortality resulting from co-occurrence of poor glycemic control and mental health problems also occurs in individuals below the age of 50. Despite this gap identified, there were some limitations in this review. The inclusion of randomized controlled trials, generally considered the gold standard of research in yielding the highest quality of evidence of the effectiveness of interventions, may have limited the scope of the evidence. It is possible that studies may have been missed given that randomized controlled trials are expensive to run and owing to limited resources, studies may have utilized inexpensive study designs such as observational studies and non-randomized controlled trials in illuminating knowledge related to non-specialist delivered psychological interventions.

The review highlighted variability of the interventions, outcomes as well as different types of non-specialists who vary with respect to their basic competencies and abilities to deliver intervention even with training. This prevented cross-comparison and quantitative analysis of the interventions’ effects on patient outcomes thus, precluding a comprehensive view of the effectiveness of non-specialist delivered psychological interventions. The review examined only English articles and exclusion of different languages may have influenced the results. Despite all the studies being RCTs, the overall evidence was of low-quality owing to the limitations in study design and implementation of the included trials, as well as the inconsistency of the effects across the included trials (see Appendix 3). Risk of bias assessments highlighted concerns about insufficient information on sequence generation and allocation concealment. However, given that included studies reported non-significant results, it is less likely that there is publication bias. Most of the studies did not satisfy the criterion that participants were blinded to treatment allocation and outcomes assessors, even though it is possible to blind outcome assessment. However, it should be noted that it is difficult to blind participants in psychological interventions [22]. The generalizability of the findings needs to be made with caution given that few trials that met the inclusion criteria, the majority of which had small sample sizes. Despite the low quality of evidence from the included studies, they are still informative of the potential effectiveness of non-specialist delivered psychological interventions, especially given the congruency of some of the results with effects of non-specialist delivered psychological interventions in the general population and other chronic conditions [31, 58].

Conclusion

In individuals with T2DM, there is some beneficial effects of non-specialist delivered psychological intervention on glycemic control, depression and diabetes distress. However, this is based on a small number of studies with heterogeneous interventions and reporting of outcomes. Given the broad range of non-specialists, the literature does not yet support definitive recommendations about which specific non-specialist holds the most promise, highlighting the need for further research. The psychological interventions found in this review such as PST, CBT and MI have been recommended as psychological treatments for delivery by non-specialists in low- and middle-income countries, including sub-Saharan Africa [52, 59]. Despite the relevance of the findings of this review to these settings, more research needs to be done in low- and middle-income countries to provide more evidence of the potential effectiveness of non-specialist delivered psychological intervention for individuals living with T2DM as the studies included in this review all come from high income countries. In addition to qualitative research investigating the quality of the relationships between intervention providers and recipients, future interventions would benefit from comprehensive classification of non-specialists, including the psychological interventions they provide, in order to understand the basic competencies needed for successful delivery as well as to ensure availability of comparable and standardized interventions.

Availability of data and materials

Not applicable.

Abbreviations

- AIDS:

-

Acquired Immune Deficiency Syndrome

- CASM:

-

Computer-Assisted Self-Management

- CAPS:

-

Computer-Assisted self-management with Problem Solving therapy

- CBT:

-

Cognitive Behavior Therapy

- CCT:

-

Client Centered Therapy

- CES-D:

-

Center for Epidemiological Studies-Depression scale

- CI:

-

Confidence Interval

- cRCT:

-

Cluster Randomized Controlled Trial

- DDS:

-

Diabetes Distress Scale

- GRADE:

-

Grading of Recommendations, Assessment, Development and Evaluations

- LA:

-

Leap Ahead

- HbA1c:

-

Glycated Hemoglobin

- HIV:

-

Human Immunodeficiency Virus

- MI:

-

Motivational Interviewing

- PAID:

-

Problem Areas in Diabetes

- PRISMA:

-

Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic reviews and Meta-Analyses

- PHQ:

-

Patient Health Questionnaire

- PST:

-

Problem Solving Therapy

- RCT:

-

Randomized Controlled Trials

- SD:

-

Standard Deviation

- SMD:

-

Standardized Mean Difference

- T2DM:

-

Type 2 Diabetes Mellitus

- UK:

-

United Kingdom

- USA:

-

United States of America

References

International Diabetes Federation. IDF Diabetes Atlas, 9th edition. 2019. https://diabetesatlas.org/key-messages.html. Accessed 5 Mar 2020.

Lin EHB, Von Korff M, Alonso J, Angermeyer MC, Anthony J, Bromet E, Bruffaerts R, Gasquet I, de Girolamo G, Gureje O, Haro JM, Karam E, Lara C, Lee S, Levinson D, Ormel JH, Posada-Villa J, Scott K, Watanabe M, Williams D. Mental disorders among persons with diabetes–results from the World Mental Health Surveys. J Psychosom Res. 2008;65(6):571–80.

Fisher L, Skaff MM, Mullan JT, Arean P, Glasgow R, Masharani UA. Longitudinal study of affective and anxiety disorders, depressive affect and diabetes distress in adults with type 2 diabetes. Diabet Med. 2008;25(9):1096–101.

Nefs AAG, van Dulmen S, Eide E, Finset A, Kristjánsdóttir ÓB, Steen IS, Eide H. The development and feasibility of a web-based intervention with diaries and situational feedback via smartphone to support self-management in patients with diabetes type 2. Diabetes Res Clin Pract. 2012;97(3):385–93.

Chen PC, Chan YT, Chen HF, Ko MC, Li CY. Population-based cohort analyses of the bidirectional relationship between type 2 diabetes and depression. Diabetes Care. 2013;36(2):376–82.

Engum A. The role of depression and anxiety in onset of diabetes in a large population-based study. J Psychosom Res. 2007;62(1):31–8.

Ali S, Stone MA, Peters JL, Davies MJ, Khunti K. The prevalence of co-morbid depression in adults with Type 2 diabetes: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Diabet Med. 2006;23(11):1165–73.

Khuwaja AK, Lalani S, Dhanani R, Azam IS, Rafique G, White F. Anxiety and depression among outpatients with type 2 diabetes: a multi-centre study of prevalence and associated factors. Diabetol Metab Syndr. 2010;2(1):72.

Gahlan D, Rajput R, Gehlawat P, Gupta R. Prevalence and determinants of diabetes distress in patients of diabetes mellitus in a tertiary care centre. Diabetes Metab Syndr. 2018;12(3):333–6.

Zhang J, Xu C, Li Y, Liu Q-Z, Wu H-X, Xu Z-J, Xue X-J, Gao Q. (2013) Comparative study of the influence of diabetes distress and depression on treatment adherence in Chinese patients with type 2 diabetes: a cross-sectional survey in the People’s Republic of China. Neuropsychiatr Dis Treat. 2013;9:1289–94.

Ciechanowski PS, Katon WJ, Russo JE. Depression and diabetes. Arch Intern Med. 2000;160(21):3278–85.

de Groot M, Anderson R, Freedland KE, Clouse RE, Lustman PJ. Association of depression and diabetes complications: a meta-analysis. Psychosom Med. 2001;63(4):619–30.

Hutter N, Schnurr A, Baumeister H. Healthcare costs in patients with diabetes mellitus and comorbid mental disorders—a systematic review. Diabetologia. 2010;53(12):2470–9.

Lustman PJ, Anderson RJ, Freedland KE, de Groot M, Carney RM, Clouse RE. Depression and poor glycemic control: a meta-analytic review of the literature. Diabetes Care. 2000;23(7):934–42.

Akena D, Kadama P, Ashaba S, Akello C, Kwesiga B, Rejani L, Okello J, Mwesiga EK, Obuku EA. The association between depression, quality of life, and the health care expenditure of patients with diabetes mellitus in Uganda. J Affect Disord. 2015;17(4):7–12.

Ibrahim A, Mubi B, Omeiza B, Wakil M, Rabbebe I, Jidda M, Ogunlesi A. An assignment of depression and quality of life among adult with diabetes mellitus in the University of Maiduguri Teaching Hospital. Internet J Psychiatry. 2013;2(1):1–8.

Mossie TB, Berhe GH, Kahsay GH, Tareke M. Prevalence of depression and associated factors among diabetic patients at Mekelle City, North Ethiopia. Indian J Psychol Med. 2017;39(1):52–8.

Chapman A, Liu S, Merkouris S, Enticott JC, Yang H, Browning CJ, Thomas SA. Psychological interventions for the management of glycemic and psychological outcomes of type 2 diabetes mellitus in china: a systematic review and meta-analyses of randomized controlled trials. Front Public Health. 2015;3:252.

Ismail K, Winkley K, Rabe-Hesketh S. Systematic review and meta-analysis of randomised controlled trials of psychological interventions to improve glycaemic control in patients with type 2 diabetes. Lancet. 2004;363(9421):1589–97.

van der Feltz-Cornelis CM, Nuyen J, Stoop C, Chan J, Jacobson AM, Katon W, Snoek F, Sartorius N. Effect of interventions for major depressive disorder and significant depressive symptoms in patients with diabetes mellitus: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Gen Hosp Psychiatry. 2010;32(4):380–95.

Uchendu C, Blake H. Effectiveness of cognitive-behavioural therapy on glycaemic control and psychological outcomes in adults with diabetes mellitus: a systematic review and meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. Diabet Med. 2017;34(3):328–39.

Chew BH, Vos RC, Metzendorf MI, Scholten RJ, Rutten GE. Psychological interventions for diabetes-related distress in adults with type 2 diabetes mellitus. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2017. https://doi.org/10.1002/14651858.CD011469.pub2.

Winkley K, Upsher R, Stahl D, Pollard D, Brennan A, Heller SR, Ismail K. Psychological interventions to improve glycemic control in adults with type 2 diabetes: a systematic review and meta-analysis. BMJ Open Diabetes Res Care. 2020;8:e001150.

Mental Health Atlas 2020. Geneva: World Health Organization; 2021.

Husain N, Chaudhry N, Fatima B, Husain M, Amin R, Chaudhry IB, Ur Rahman R, Tomenson B, Jafri F, Naeem F, Creed F. Antidepressant and group psychosocial treatment for depression: a rater blind exploratory RCT from a low income country. Behav Cogn Psychother. 2014;42(6):693–705.

Naeem F, Waheed W, Gobbi M, Ayub M, Kingdon D. Preliminary evaluation of culturally sensitive CBT for depression in Pakistan: findings from developing culturally-sensitive CBT Project (DCCP). Behav Cogn Psychother. 2011;39(2):165–73.

Sumathipala A, Siribaddana S, Abeysingha MRN, De Silva P, Dewey M, Prince M, Mann AH. Cognitive-behavioural therapy v. structured care for medically unexplained symptoms: randomised controlled trial. Br J Psychiatry. 2008;193(1):51–9.

Liberati A, Altman DG, Tetzlaff J, Mulrow C, Gøtzsche PC, Ioannidis JP, Clarke M, Devereaux PJ, Kleijnen J, Moher D. The PRISMA statement for reporting systematic reviews and meta-analyses of studies that evaluate health care interventions: explanation and elaboration. J Clin Epidemiol. 2009;62(10):1–34.

Hoeft TJ, Fortney JC, Patel V, Jürgen U. Task-sharing approaches to improve mental health care in rural and other low-resource settings: a systematic review. J Rural Health. 2018;34(1):48–62.

Singla DR, Kohrt BA, Murray LK, Anand A, Chorpita BF, Patel V. Psychological treatments for the world: lessons from low- and middle-income countries. Annu Rev Clin Psychol. 2017;13(1):149–81.

Van Ginneken N, Tharyan P, Lewin S, Rao GN, Meera SM, Pian J, Chandrashekar S, Patel V. Non-specialist health worker interventions for the care of mental, neurological and substance-abuse disorders in low-and middle-income countries. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2013. https://doi.org/10.1002/14651858.CD009149.pub2.

Stoll CRT, Izadi S, Fowler S, Green P, Suls J, Colditz GA. The value of a second reviewer for study selection in systematic reviews. Res Synthesis Methods. 2019;10(4):539–45.

Higgins JP, Altman DG, Gøtzsche PC, Jüni P, Moher D, Oxman AD, Savović J, Schulz KF, Weeks L, Sterne JA. The Cochrane Collaboration’s tool for assessing risk of bias in randomised trials. Br Med J. 2011;343:d5928.

Becker LA. Effect Size (ES). 2000. http://www.bwgriffin.com/gsu/courses/edur9131/content/EffectSizeBecker.pdf. Accessed 6 Nov 2020.

Chiu CJ, Hu YH, Wray LA, Beverly EA, Yang YC, Wu JS, Lu FH. Dissemination of evidence-base minimal psychological intervention for diabetes management in Taiwan adults with type 2 diabetes. Int J Clin Exp Med. 2016;9(7):14489–98.

Dale J, Caramlau I, Sturt J, Frede T, Walker R. Telephone peer-delivered intervention for diabetes motivation and support: the telecare exploratory RCT. Patient Educ Counsel. 2009;75(1):91–8.

Döbler A, Herbeck Belnap B, Pollmann H, Farin E, Raspe H, Mittag O. Telephone-delivered lifestyle support with action planning and motivational interviewing techniques to improve rehabilitation outcomes. Rehabil Psychol. 2018;63(2):170–81.

Fisher L, Hessler D, Glasgow RE, Arean PA, Masharani U, Naranjo D, Strycker LA. REDEEM: a pragmatic trial to reduce diabetes distress. Diabetes Care. 2013;36(9):2551–8.

Gabbay RA, Añel-Tiangco RM, Dellasega C, Mauger DT, Adelman A, Van DH. Diabetes nurse case management and motivational interviewing for change (DYNAMIC): results of a 2-year randomized controlled pragmatic trial. J Diabetes. 2013;5(3):349–57.

Heinrich E, Candel MJJM, Schaper NC, de Vries NK. Effect evaluation of a motivational interviewing based counselling strategy in diabetes care. Diabetes Res Clin Pract. 2010;90:270–8.

Inouye J, Li D, Davis J, Arakaki R. Psychosocial and clinical outcomes of a cognitive behavioral therapy for asians and pacific islanders with type 2 diabetes: a randomized clinical trial. Hawai’i J Med Public Health. 2015;74(11):360.

Kim MT, Kim KB, Huh B, Nguyen T, Han H, Bone LR, Levine D. The effect of a community-based self-help intervention Korean Americans with type 2 diabetes. Am J Prev Med. 2015;49(5):726–37.

Lamers F, Jonkers CC, Bosma H, Knottnerus JA, van Eijk JTM. Treating depression in diabetes patients: does a nurse-administered minimal psychological intervention affect diabetes-specific quality of life and glycaemic control? A randomized controlled trial. J Adv Nurs. 2011;67(4):788–99.

Sacco WP, Malone JI, Morrison AD, Friedman A, Wells K. Effect of a brief, regular telephone intervention by paraprofessionals for type 2 diabetes. J Behav Med. 2009;32(4):349–59.

Simmons D, Prevost AT, Bunn C, Holman D, Parker RA, Cohn S, Donald S, Paddison CA, Ward C, Robins P, Graffy J. Impact of community based peer support in type 2 diabetes: a cluster randomised controlled trial of individual and/or group approaches. PLoS One. 2015;10(3):e0120277.

Spencer MS, Hawkins J, Espitia NR, Sinco B, Jennings T, Lewis C, Palmisano G, Kieffer E. Influence of a community health worker intervention on mental health outcomes among low-income Latino and African American adults with type 2 diabetes. Race Soc Probl. 2013;5(2):137–46.

Wagner JA, Bermudez-Millan A, Damio G, Segura-Perez S, Chhabra J, Vergara C, Feinn R, Perez-Escamilla R. A randomized, controlled trial of a stress management intervention for Latinos with type 2 diabetes delivered by community health workers: outcomes for psychological wellbeing, glycemic control, and cortisol. Diabetes Res Clin Pract. 2016;120:162–70.

Welch G, Zagarins SE, Feinberg RG, Garb JL. Motivational interviewing delivered by diabetes educators:does it improve blood glucose control among poorly controlled type 2 diabetes patients? Diabetes Res Clin Pract. 2011;91(1):54–60.

Welschen LM, van Oppen P, Bot SD, Kostense PJ, Dekker JM, Nijpels G. Effects of a cognitive behavioural treatment in patients with type 2 diabetes when added to managed care; a randomised controlled trial. J Behav Med. 2013;36(6):556–66.

Whittemore R, Melkus GDE, Sullivan A, Grey M. A nurse-coaching intervention for women with type 2 diabetes. Diabetes Educ. 2004;30(5):795–804.

Schmidt CB, van Loon BJP, Vergouwen ACM, Snoek FJ, Honig A. Systematic review and meta-analysis of psychological interventions in people with diabetes and elevated diabetes-distress. Diabet Med. 2018;35(9):1157–72.

Beres LK, Narasimhan M, Robinson J, Welbourn A, Kennedy CE. Non-specialist psychosocial support interventions for women living with HIV: a systematic review. AIDS Care. 2017;29(9):1079–87.

Nash VR, Ponto J, Townsend C, Nelson P, Bretz MN. Cognitive behavioral therapy, self-efficacy and depression in persons with chronic pain. Pain Manag Nurs. 2013;14(4):236–43.

Tobin K, Davey-Rothwell MA, Nonyane BAS, Knowlton A, Wissow L, Latkin CA. RCT of an integrated CBT-HIV intervention on depressive symptoms and HIV risk. PLoS ONE. 2017;12(12):e0187180.

Lundahl BW, Kunz C, Brownell C, Tollefson D, Burke BL. A meta-analysis of motivational interviewing: twenty-five years of empirical studies. Res Soc Work Pract. 2010;20(2):137–60.

Wampold BE, Imel ZE. The great psychotherapy debate. 2nd ed. New York: Routledge; 2015.

Sturt J, Dennick K, Hessler D, Hunter BM, Oliver J, Fisher L. Effective interventions for reducing diabetes distress: systematic review and meta-analysis. Int Diabetes Nurs. 2015;12(2):40–55.

Spedding MF, Stein DJ, Sorsdahl K. Task-shifting psychosocial interventions in public mental health: a review of the evidence in the South African context. South Afr Health Rev. 2014;1:73–87.

World Health Organization. mhGAP Intervention Guide Mental Health Gap Action Programme Version 2.0 for mental, neurological and substance use disorders in non-specialized health settings. 2016. http://www.who.int. Accessed 5 Feb 2020.

Acknowledgements

We would wish to acknowledge the contributions of the ScHARR library team in helping with the databases for the literature search. We would also like to thank Prof. Femke Lamers and Prof. Michael Spencer for providing additional information.

Funding

We received no specific funding for this work.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

AO: conceptualization, methodology, writing-original draft. IU: validation. SW: supervision, writing-review & editing. RB: supervision, writing-review & editing. AB: writing-review & editing. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

Not applicable.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Appendices

Appendices

Appendices contents:

-

Appendix 1: Systematic review search strategies

-

Appendix 2: Data extraction form

-

Appendix 3: Grade assessment

-

Appendix 4: Forest plot for a random-effect meta-analysis of standardized mean difference in HbA1c comparing health professionals and non-health professionals

Appendix 1: Systematic review search strategies

EMBASE (Ovid SP)

-

1)

Paramedical Personnel/

-

2)

Health Auxiliary/

-

3)

Nursing Assistant/

-

4)

Caregiver/

-

5)

Voluntary Worker/

-

6)

Self Help/

-

7)

Social Support/

-

8)

Health Care Manpower/

-

9)

(lay adj3 (worker? or visitor? or attendant? or aide or aides or support* or person* or helper? or carer? or caregiver? or care giver? or consultant? or advisor? or counselor? or counsellor? or assistant? or staff)).ti,ab.

-

10)

((voluntary or volunteer?) adj3 (worker? or visitor? or attendant? or aide or aides or support* or person* or helper? or carer? or caregiver? or care giver? or consultant? or advisor? or counselor? or counsellor? or assistant? or staff)).ti,ab.

-

11)

(untrained adj3 (worker? or visitor? or attendant? or aide or aides or support* or person* or helper? or carer? or caregiver? or care giver? or consultant? or advisor? or counselor? or counsellor? or assistant? or staff or nurse? or doctor? or physician? or therapist?)).ti,ab.

-

12)

(trained adj3 (worker? or visitor? or attendant? or aide or aides or support* or person* or helper? or carer? or caregiver? or care giver? or consultant? or advisor? or counselor? or counsellor? or assistant? or staff or nurse? or doctor? or physician? or therapist?)).ti,ab.

-

13)

(unlicensed adj3 (worker? or visitor? or attendant? or aide or aides or support* or person* or helper? or carer? or caregiver? or care giver? or consultant? or advisor? or counselor? or counsellor? or assistant? or staff or nurse? or doctor? or physician? or therapist?)).ti,ab.

-

14)

((nonprofessional? or non professional?) adj3 (worker? or visitor? or attendant? or aide or aides or support* or person* or helper? or carer? or caregiver? or care giver? or consultant? or advisor? or counselor? or counsellor? or assistant? or staff)).ti,ab.

-

15)

((non medical or non health or non healthcare or non health care) adj3 (worker? or visitor? or attendant? or aide or aides or support* or person* or helper? or carer? or caregiver? or care giver? or consultant? or advisor? or counselor? or counsellor? or assistant? or staff)).ti,ab.

-

16)

(community adj3 (worker? or visitor? or attendant? or aide or aides or support* or person* or helper? or carer? or caregiver? or care giver? or consultant? or advisor? or counselor? or counsellor? or assistant? or staff)).ti,ab.

-

17)

(paraprofessional? or paramedic or paramedics or paramedical worker? or paramedical personnel or allied health personnel or allied health worker? or support worker? or non specialist? or specially trained or barefoot doctor? or nurs* aid* or psychiatric aide? or psychiatric attendant? or social worker? or teacher? or school staff or trainer?).ti,ab.

-

18)

((health* or medical*) adj3 (auxiliary or auxiliaries)).ti,ab.

-

19)

(nurs* adj1 (auxiliary or auxiliaries)).ti,ab.

-

20)

(informal adj (caregiver? or care giver? or carer?)).ti,ab.

-

21)

(self help group? or support group?).ti,ab.

-

22)

((social or psychosocial) adj (care or support)).ti,ab.

-

23)

(village adj3 worker?).ti,ab.

-

24)

community based.ti,ab.

-

25)

(community adj3 intervention?).ti,ab.

-

26)

community network?.ti,ab.

-

27)

((health or health care or healthcare) adj manpower).ti,ab.

-

28)

human resources.ti,ab.

-

29)

(task? adj3 shift*).ti,ab.

-

30)

(staff* adj3 chang*).ti,ab.

-

31)

1 or 2 or 3 or 4 or 5 or 6 or 7 or 8 or 9 or 10 or 11 or 12 or 13 or 14 or 15 or 16 or 17 or 18 or 19 or 20 or 21 or 22 or 23 or 24 or 25 or 26 or 27 or 28 or 29 or 30

-

32)

((typ? 2 or typ? II or typ?2 or typ?II) adj3 diabet$).tw,ot.

-

33)

(non insulin$ depend$ or noninsulin$ depend$ or non insulin? depend$).mp. or noninsulin?depend$.tw,ot.

-

34)

diabetes mellitus/ or diabetes mellitus, type 2/

-

35)

32 or 33 or 34

-

36)

(problem? area? adj3 diabetes).tw.

-

37)

(diabet* adj12 distress*).tw.

-

38)

(((diabet* adj3 specific) or related) adj3 stress).tw.

-

39)

diabet* stress.tw.

-

40)

psycho* stress$.tw.

-

41)

emotion$ distr$.tw.

-

42)

depress*.mp. [mp = title, abstract, heading word, drug trade name, original title, device manufacturer, drug manufacturer, device trade name, keyword, floating subheading word, candidate term word]

-

43)

(((depressi$ adj3 disorder$) or depressi$) adj3 symptom$).tw,ot.

-

44)

36 or 37 or 38 or 39 or 40 or 41 or 42 or 43

-

45)

31 and 35 and 44

-

46)

random*.tw. or clinical trial*.mp. or exp health care quality/

-

47)

Randomized Controlled Trial/

-

48)

Controlled Clinical Trial/

-

49)

(randomised or randomized or randomly).ti,ab.

-

50)

intervention*.ti,ab.

-

51)

evaluat*.ti,ab.

-

52)

control*.ti,ab.

-

53)

effect?.ti,ab.

-

54)

impact.ti,ab.

-

55)

((pretest or pre test) and (posttest or post test)).ti,ab.

-

56)

46 or 47 or 48 or 49 or 50 or 51 or 52 or 53 or 54 or 55

-

57)

45 and 56

Cinahl (Ebscohost)

S64 | S34 AND S37 AND S54 AND S63 |

S63 | S55 OR S56 OR S57 OR S58 OR S59 OR S60 OR S61 OR S62 |

S62 | PT clinical trial |

S61 | MH “Pretest–Posttest Design+” |

S60 | MH “Clinical Trials” |

S59 | TI (randomis* or randomiz* or random* W0 allocat*) OR AB (randomis* or randomiz* or random* W0 allocat*) |

S58 | PT research |

S57 | TI (intervention* or controlled or control W0 group* or compare or compared or before N5 after or pre N5 post or pretest or “pre test” or posttest or “post test” or evaluat* or effect or impact or repeated W0 measur*) OR AB (intervention* or controlled or control W0 group* or compare or compared or before N5 after or pre N5 post or pretest or “pre test” or posttest or “post test” or evaluat* or effect or impact or repeated W0 measur*) |

S56 | MH “Randomized Controlled Trials” |

S55 | MH “prognosis+” OR MH “study design+” or random* |

S54 | S38 OR S39 OR S40 OR S41 OR S42 OR S43 OR S44 OR S45 OR S46 OR S47 OR S48 OR S49 OR S50 OR S51 OR S52 OR S53 |

S53 | AB (depress* N3 disorder*) |

S52 | TI (depress* N3 disorder*) |

S51 | AB (“depress*”) |

S50 | TI (“depress*”) |

S49 | AB (“psych* stress”) |

S48 | TI (“psych* stress”) |

S47 | AB (“emotion* stress”) |

S46 | TI (“emotion* stress”) |

S45 | AB (“diabet* stress”) |

S44 | TI (“diabet* stress”) |

S43 | AB (diabet* N3 (specific OR related) N3 stress) |

S42 | TI (diabet* N3 (specific OR related) N3 stress) |

S41 | AB (diabet* N12 distress*) |

S40 | TI (diabet* N12 distress*) |

S39 | AB (“problem# area#” N3 diabetes) |

S38 | TI (“problem# area#” N3 diabetes) |

S37 | S35 OR S36 |

S36 | TI type 2 diabetes or type 2 diabetes mellitus or t2dm |

S35 | AB (“type 2 diabetes*) |

S34 | S1 OR S2 OR S3 OR S4 OR S5 OR S6 OR S7 OR S8 OR S9 OR S10 OR S11 OR S12 OR S13 OR S14 OR S15 OR S16 OR S17 OR S18 OR S19 OR S20 OR S21 OR S22 OR S23 OR S24 OR S25 OR S26 OR S27 OR S28 OR S29 OR S30 OR S31 OR S32 OR S33 |

S33 | TI staff* N3 chang* OR AB staff* N3 chang* |

S32 | TI ((task or tasks) N3 shift*) OR AB ((task or tasks) N3 shift*) |

S31 | TI “human resources” OR AB “human resources” |

S30 | TI ((health or healthcare) W0 manpower) OR AB ((health or healthcare) W0 manpower) |

S29 | TI community W0 network* OR AB community W0 network* |

S28 | TI community N3 intervention* OR AB community N3 intervention* |

S27 | TI “community based” OR AB “community based” |

S26 | TI village N3 worker* OR AB village N3 worker* |

S25 | TI ((social or psychosocial) W0 (care or support)) OR AB ((social or psychosocial) W0 (care or support)) |

S24 | TI (“self help group” or “self help groups” or “support group” or “support groups”) OR AB (“self help group” or “self help groups” or “support group” or “support groups”) |

S23 | TI (informal W0 (caregiver* or “care giver” or “care givers” or carer*)) OR AB (informal W0 (caregiver* or “care giver” or “care givers” or carer*)) |

S22 | TI (nurs* N1 (auxiliary or auxiliaries)) OR AB (nurs* N1 (auxiliary or auxiliaries)) |

S21 | TI ((health* or medical*) N3 (auxiliary or auxiliaries)) OR AB ((health* or medical*) N3 (auxiliary or auxiliaries)) |

S20 | TI (paraprofessional* or paramedic or paramedics or paramedical W0 worker* or paramedical W0 personnel or “allied health personnel” or “allied health worker” or “allied health workers” or support W0 worker* or non W0 specialist* or “specially trained” or barefoot W0 doctor* or nurs* W0 aide* or psychiatric W0 aide* or psychiatric W0 attendant* or social W0 worker* or teacher* or "school staff" or trainer*) OR AB (paraprofessional* or paramedic or paramedics or paramedical W0 worker* or parame… |

S19 | TI (community N3 (worker* or visitor* or attendant* or aide or aides or support* or person* or helper* or carer* or caregiver* or “care giver” or “care givers” or consultant* or advisor* or counselor* or counsellor* or assistant* or staff)) OR AB (community N3 (worker* or visitor* or attendant* or aide or aides or support* or person* or helper* or carer* or caregiver* or “care giver” or “care givers” or consultant* or advisor* or counselor* or counsellor* or assistant* or staff)) |

S18 | TI ((“non medical” or “non health” or “non healthcare”) N3 (worker* or visitor* or attendant* or aide or aides or support* or person* or helper* or carer* or caregiver* or “care giver” or “care givers” or consultant* or advisor* or counselor* or counsellor* or assistant* or staff)) OR AB ((“non medical” or “non health” or “non healthcare”) N3 (worker* or visitor* or attendant* or aide or aides or support* or person* or helper* or carer* or caregiver* or “care giver” or “care givers” or consul… |

S17 | TI ((nonprofessional* or “non professional” or “non professionals”) N3 (worker* or visitor* or attendant* or aide or aides or support* or person* or helper* or carer* or caregiver* or "care giver" or “care givers” or consultant* or advisor* or counselor* or counsellor* or assistant* or staff)) OR AB ((nonprofessional* or “non professional” or “non professionals”) N3 (worker* or visitor* or attendant* or aide or aides or support* or person* or helper* or carer* or caregiver* or "care giver" or… |

S16 | TI (unlicensed N3 (worker* or visitor* or attendant* or aide or aides or support* or person* or helper* or carer* or caregiver* or “care giver” or “care givers” or consultant* or advisor* or counselor* or counsellor* or assistant* or staff or nurse* or doctor* or physician* or therapist*)) OR AB (unlicensed N3 (worker* or visitor* or attendant* or aide or aides or support* or person* or helper* or carer* or caregiver* or “care giver” or “care givers” or consultant* or advisor* or counselor* o… |

S15 | TI (trained N3 (worker* or visitor* or attendant* or aide or aides or support* or person* or helper* or carer* or caregiver* or “care giver” or “care givers” or consultant* or advisor* or counselor* or counsellor* or assistant* or staff or nurse* or doctor* or physician* or therapist*)) OR AB (trained N3 (worker* or visitor* or attendant* or aide or aides or support* or person* or helper* or carer* or caregiver* or “care giver” or “care givers” or consultant* or advisor* or counselor* or coun… |

S14 | TI (untrained N3 (worker* or visitor* or attendant* or aide or aides or support* or person* or helper* or carer* or caregiver* or “care giver” or “care givers” or consultant* or advisor* or counselor* or counsellor* or assistant* or staff or nurse* or doctor* or physician* or therapist*)) OR AB (untrained N3 (worker* or visitor* or attendant* or aide or aides or support* or person* or helper* or carer* or caregiver* or “care giver” or “care givers” or consultant* or advisor* or counselor* or … |

S13 | TI ((voluntary or volunteer*) N3 (worker* or visitor* or attendant* or aide or aides or support* or person* or helper* or carer* or caregiver* or “care giver” or “care givers” or consultant* or advisor* or counselor* or counsellor* or assistant* or staff)) OR AB ((voluntary or volunteer*) N3 (worker* or visitor* or attendant* or aide or aides or support* or person* or helper* or carer* or caregiver* or “care giver” or “care givers” or consultant* or advisor* or counselor* or counsellor* or as… |

S12 | TI (lay N3 (worker* or visitor* or attendant* or aide or aides or support* or person* or helper* or carer* or caregiver* or “care giver” or “care givers” or consultant* or advisor* or counselor* or counsellor* or assistant* or staff)) OR AB (lay N3 (worker* or visitor* or attendant* or aide or aides or support* or person* or helper* or carer* or caregiver* or “care giver” or “care givers” or consultant* or advisor* or counselor* or counsellor* or assistant* or staff)) |

S11 | (MH “Home Health Aides”) |

S10 | (MH “Health Personnel, Unlicensed”) |

S9 | (MH “Personnel Staffing and Scheduling”) |

S8 | (MH “Health Manpower”) |

S7 | (MH “Support Groups”) |

S6 | (MH “Volunteer Workers”) |

S5 | (MH “Community Networks”) |

S4 | (MH “Caregivers”) |

S3 | (MH “Nursing Assistants”) |

S2 | (MH “Community Health Workers”) |

S1 | (MH “Allied Health Personnel”) |

Medline (Ovid SP)

-

1)

Allied Health Personnel/

-

2)

Community Health Workers/

-

3)

Nurses' Aides/

-

4)

Psychiatric Aides/

-

5)

Caregivers/

-

6)

Voluntary Workers/

-

7)

Community Networks/

-

8)

exp Self Help Groups/

-

9)

Social Support/

-

10)

Personnel Staffing.mp. and Scheduling/ [mp = title, abstract, original title, name of substance word, subject heading word, floating sub-heading word, keyword heading word, organism supplementary concept word, protocol supplementary concept word, rare disease supplementary concept word, unique identifier, synonyms]

-

11)

(lay adj3 (worker? or visitor? or attendant? or aide or aides or support* or person* or helper? or carer? or caregiver? or care giver? or consultant? or advisor? or counselor? or counsellor? or assistant? or staff)).ti,ab.

-

12)

((voluntary or volunteer?) adj3 (worker? or visitor? or attendant? or aide or aides or support* or person* or helper? or carer? or caregiver? or care giver? or consultant? or advisor? or counselor? or counsellor? or assistant? or staff)).ti,ab.

-

13)

(untrained adj3 (worker? or visitor? or attendant? or aide or aides or support* or person* or helper? or carer? or caregiver? or care giver? or consultant? or advisor? or counselor? or counsellor? or assistant? or staff or nurse? or doctor? or physician? or therapist?)).ti,ab.

-

14)

(trained adj3 (worker? or visitor? or attendant? or aide or aides or support* or person* or helper? or carer? or caregiver? or care giver? or consultant? or advisor? or counselor? or counsellor? or assistant? or staff or nurse? or doctor? or physician? or therapist?)).ti,ab.

-

15)

(unlicensed adj3 (worker? or visitor? or attendant? or aide or aides or support* or person* or helper? or carer? or caregiver? or care giver? or consultant? or advisor? or counselor? or counsellor? or assistant? or staff or nurse? or doctor? or physician? or therapist?)).ti,ab.

-

16)

((nonprofessional? or non professional?) adj3 (worker? or visitor? or attendant? or aide or aides or support* or person* or helper? or carer? or caregiver? or care giver? or consultant? or advisor? or counselor? or counsellor? or assistant? or staff)).ti,ab.

-

17)

((non medical or non health or non healthcare or non health care) adj3 (worker? or visitor? or attendant? or aide or aides or support* or person* or helper? or carer? or caregiver? or care giver? or consultant? or advisor? or counselor? or counsellor? or assistant? or staff)).ti,ab.

-

18)

(community adj3 (worker? or visitor? or attendant? or aide or aides or support* or person* or helper? or carer? or caregiver? or care giver? or consultant? or advisor? or counselor? or counsellor? or assistant? or staff)).ti,ab.

-

19)

(paraprofessional? or paramedic or paramedics or paramedical worker? or paramedical personnel or allied health personnel or allied health worker? or support worker? or non specialist? or specially trained or barefoot doctor? or nurs* aid* or psychiatric aide? or psychiatric attendant? or social worker? or teacher? or school staff or trainer?).ti,ab.

-

20)

((health* or medical*) adj3 (auxiliary or auxiliaries)).ti,ab.

-

21)

(nurs* adj1 (auxiliary or auxiliaries)).ti,ab.

-

22)

(informal adj (caregiver? or care giver? or carer?)).ti,ab.

-

23)

(self help group? or support group?).ti,ab.

-

24)

((social or psychosocial) adj (care or support)).ti,ab.

-

25)

(village adj3 worker?).ti,ab.

-

26)

community based.ti,ab.

-

27)

(community adj3 intervention?).ti,ab.

-

28)

community network?.ti,ab.

-

29)

((health or health care or healthcare) adj manpower).ti,ab.

-

30)

human resources.ti,ab.

-

31)

(task? adj3 shift*).ti,ab.

-

32)

(staff* adj3 chang*).ti,ab.

-

33)

Health Manpower/

-

34)

1 or 2 or 3 or 4 or 5 or 6 or 7 or 8 or 9 or 10 or 11 or 12 or 13 or 14 or 15 or 16 or 17 or 18 or 19 or 20 or 21 or 22 or 23 or 24 or 25 or 26 or 27 or 28 or 29 or 30 or 31 or 32 or 33

-

35)

diabetes mellitus/ or diabetes mellitus, type 2/

-

36)

((typ? 2 or typ? II or typ?2 or typ?II) adj3 diabet$).tw,ot.

-

37)

(non insulin$ depend$ or noninsulin$ depend$ or non insulin? depend$).mp. or noninsulin?depend$.tw,ot.

-

38)

35 or 36 or 37

-

39)

(problem? area? adj3 diabetes).tw.

-

40)

(diabet* adj12 distress*).tw.

-

41)

(((diabet* adj3 specific) or related) adj3 stress).tw.

-

42)

diabet* stress.tw.

-

43)

psycho* stress$.tw.

-

44)

emotion$ distr$.tw.

-

45)

depress*.mp. [mp = title, abstract, original title, name of substance word, subject heading word, floating sub-heading word, keyword heading word, organism supplementary concept word, protocol supplementary concept word, rare disease supplementary concept word, unique identifier, synonyms]

-

46)

(((depressi$ adj3 disorder$) or depressi$) adj3 symptom$).tw,ot.

-

47)

39 or 40 or 41 or 42 or 43 or 44 or 45 or 46

-

48)

Random* Control* Trial*.mp. [mp = title, abstract, original title, name of substance word, subject heading word, floating sub-heading word, keyword heading word, organism supplementary concept word, protocol supplementary concept word, rare disease supplementary concept word, unique identifier, synonyms]

-

49)

Random* Control* Trial*.ti.

-

50)

(Clinical Trials or Controlled Clinical Trial*).mp. [mp = title, abstract, original title, name of substance word, subject heading word, floating sub-heading word, keyword heading word, organism supplementary concept word, protocol supplementary concept word, rare disease supplementary concept word, unique identifier, synonyms]

-

51)

((Random* adj2 sampl*) or allocat*).mp. [mp = title, abstract, original title, name of substance word, subject heading word, floating sub-heading word, keyword heading word, organism supplementary concept word, protocol supplementary concept word, rare disease supplementary concept word, unique identifier, synonyms]

-

52)

((Random* adj Clinical Trial*) or Controlled Clinical Trial*).mp. [mp = title, abstract, original title, name of substance word, subject heading word, floating sub-heading word, keyword heading word, organism supplementary concept word, protocol supplementary concept word, rare disease supplementary concept word, unique identifier, synonyms]

-

53)

evaluat*.ti,ab.

-

54)

effect?.ti,ab.

-

55)

impact.ti,ab.

-

56)

trial.ti,ab.

-

57)

((pretest or pre test) and (posttest or post test)).ti,ab.

-

58)

((multicenter or multicentre or multi center or multi centre) adj study).ti,ab.

-

59)

repeated measure*.ti,ab.

-

60)

34 and 38 and 47

-

61)

48 or 49 or 50 or 51 or 52 or 53 or 54 or 55 or 56 or 57 or 58 or 59

-

62)

60 and 61

PsycINFO (Ovid SP)

-

1)

Allied Health Personnel/

-

2)

Nonprofessional Personnel/

-

3)

Paraprofessional Personnel/

-

4)

Psychiatric Aides/

-

5)

Home Care Personnel/

-

6)

Caregivers/

-

7)

Volunteers/

-

8)

Support Groups/

-

9)

Social Support/

-

10)

(lay adj3 (worker? or visitor? or attendant? or aide or aides or support* or person* or helper? or carer? or caregiver? or care giver? or consultant? or advisor? or counselor? or counsellor? or assistant? or staff)).ti,ab.

-

11)

((voluntary or volunteer?) adj3 (worker? or visitor? or attendant? or aide or aides or support* or person* or helper? or carer? or caregiver? or care giver? or consultant? or advisor? or counselor? or counsellor? or assistant? or staff)).ti,ab.

-

12)

(untrained adj3 (worker? or visitor? or attendant? or aide or aides or support* or person* or helper? or carer? or caregiver? or care giver? or consultant? or advisor? or counselor? or counsellor? or assistant? or staff or nurse? or doctor? or physician? or therapist?)).ti,ab.

-

13)

(trained adj3 (worker? or visitor? or attendant? or aide or aides or support* or person* or helper? or carer? or caregiver? or care giver? or consultant? or advisor? or counselor? or counsellor? or assistant? or staff or nurse? or doctor? or physician? or therapist?)).ti,ab.

-

14)