Abstract

The association between poor mental health and factors related to HIV acquisition and disease progression (also referred to as HIV-related factors) may be stronger among conflict-affected populations given elevated rates of mental health disorders. We conducted a scoping review of the literature to identify evidence-based associations between mental health (depression, anxiety, and post-traumatic stress disorder [PTSD]) and factors related to HIV acquisition and progression in conflict-affected populations. Five electronic databases were searched on October 10, 2014 and updated on March 7, 2017 to identify peer-reviewed publications presenting primary data from January 1, 1994 to March 7, 2017. Articles were included if: 1) depression, anxiety, and/or PTSD was assessed using a validated scale, 2) HIV or HIV-related factors were a primary focus, 3) quantitative associations between depression/anxiety/PTSD and HIV or HIV-related factors were assessed, and 4) the study population was conflict-affected and from a conflict-affected setting. Of 714 citations identified, 33 articles covering 110,818 participants were included. Most were from sub-Saharan Africa (n = 25), five were from the USA, and one each was from the Middle East, Europe, and Latin America. There were 23 cross-sectional, 3 time-series, and 7 cohort studies. The search identified that mental health has been quantitatively associated with the following categories of HIV-related factors in conflict-affected populations: markers of HIV risk, HIV-related health status, sexual risk behaviors, and HIV risk exposures (i.e. sexual violence). Further, findings suggest that symptoms of poor mental health are associated with sexual risk behaviors and HIV markers, while HIV risk exposures and health status are associated with symptoms of poor mental health. Results suggest a role for greater integration and referrals across HIV and mental health programs for conflict-affected populations.

Similar content being viewed by others

Background

The relationship between mental health and HIV acquisition and disease progression (also referred to as HIV-related factors) is bi-directional. Having symptoms of post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD), depression, and/or anxiety has been linked to HIV risk factors in various populations both prospectively [1] and cross-sectionally [2,3,4,5,6]. Being HIV-positive physiologically, psychologically, and socially increases risk for neuropsychiatric conditions [7]. In this paper we consider a broad range of factors associated with HIV acquisition and disease progression, such as markers of HIV risk, HIV-related health status, sexual risk behaviors, and other potential HIV risk exposures not under individual control (i.e. sexual violence).

As conflict-affected populations often have elevated rates of PTSD, depression, and anxiety [8,9,10,11,12], the association between poor mental health and risk for HIV acquisition and disease progression may be stronger among these populations. Conflict can shape population movements, opportunities for sexual partnering, and mortality patterns in ways that might increase or decrease HIV prevalence [13, 14]. Epidemiological evidence suggests elevated HIV prevalence in the five years prior to conflict, but an overall decrease in HIV prevalence during and just after conflict [15, 16]. However, vulnerable populations may remain at elevated risk for HIV acquisition during political and socioeconomic instability [14, 17]. A seminal paper discussing population vulnerability to HIV transmission in conflict-affected settings discusses health factors but does not detail the ways poor mental health can impact population vulnerability to HIV [13]. Poor mental health, conflict, and being HIV positive are independently related to morbidity and mortality. Co-occurrence of these factors can contribute to increased vulnerability to morbidity and mortality.

Other reviews that have examined associations between mental health and HIV risk behaviors or care and treatment programs have focused on migrant populations [18] and populations from developing countries [18, 19]. It is yet unknown how the vulnerabilities of poor mental health and factors related to HIV acquisition and disease progression operate in conflict-affected populations. Understanding how mental health is associated with HIV acquisition and disease progression in conflict-affected populations can inform program and policy work in these settings. The aim of our study was to conduct a scoping review of the literature to identify evidence-based associations between common mental health conditions (depression, anxiety, and PTSD) and factors related to HIV acquisition and disease progression in conflict-affected populations. We sought to understand the bi-directional associations between these mental health conditions and various measures of HIV-related factors, and to examine the strength and directionality of associations to offer suggested directions for future research, policy, and interventions.

Methods

Peer-reviewed publications that presented primary data from January 1, 1994 to March 7, 2017 were included in this review if they met the following inclusion criteria: 1) one or more of three common mental health conditions (depression, anxiety, PTSD) was a primary or substantive focus of the article and was assessed using a validated scale, 2) HIV serostatus or factors related to HIV acquisition and disease progression (defined below) was a primary or substantive focus of the article, 3) the quantitative relationship between HIV or HIV-related factors and the mental health condition(s) was discussed, and 4) the study reported that participants were conflict-affected and from a conflict-affected setting. All age groups were included in this review. All study designs were considered as long as the four inclusion criteria were met. Articles were excluded if they measured HIV-related factors on a war events scale but did not present data for the relationship between the HIV-related factor alone and mental health measures. This review was conducted following PRISMA guidelines [20].

Definition of terms

We sought to illuminate the ways a broad range of factors related to HIV acquisition and disease progression have been examined in relationship to mental health. Therefore, we defined factors related to HIV acquisition and disease progression to include factors such as: markers of HIV risk (i.e. sexually transmitted infections (STIs)); HIV-related health status (i.e. HIV seropositive status, CD4 count); sexual risk behaviors (e.g. unprotected sex, multiple sexual partners, exchange sex, etc.); and other potential HIV exposures not under individual control (i.e. sexual assault). A range of factors related to HIV were included in order to provide a comprehensive understanding of how researchers have quantitatively examined the relationships between specific mental health disorders and HIV-related factors.

Conflict-affected settings were defined according to UNESCO as areas with ‘explosive’ (over 200 battle-related deaths in a year) or ‘protracted’ (over 1000 battle-related deaths over ten years) events [21]. Both active conflict and post-conflict settings were included. Since not all populations in conflict-affected countries are directly affected by conflict, the study population had to be affected by conflict and described as such by the article’s authors. All combat-affected populations were considered for inclusion, both combatants and civilians. Conflict-affected populations across the economic spectrum were considered for inclusion to examine the relationship between mental health and HIV-related factors in a variety of economic situations.

Search strategy

Five electronic databases (PubMed, PsycINFO, SCOPUS, CINAHL, and EMBASE) were searched first on October 10, 2014 and updated on March 7, 2017. Search terms included combinations of terms for mental health, HIV risk, and conflict-affected settings (Additional file 1). We also searched reference lists of included articles and hand searched the table of contents of Conflict and Health and Medicine Conflict and Survival. Only articles with an abstract in English were screened.

Data extraction and management

Articles were screened and data extracted by one reviewer (EK), with uncertainty resolved through discussion with a second reviewer (CK). A third reviewer verified all data presented in Tables 1 and 2. First, titles and abstracts identified through the search strategy were screened. Full text articles were obtained for all selected abstracts. An eligibility form was completed to determine final study selection. Data were extracted using a standardized data extraction spreadsheet. For each included study the following information was extracted where applicable: citation; location, setting and target group; study design; sample size; age range; gender; random or non-random selection of participants; length of follow up; outcome measures; comparison groups; effect sizes; confidence intervals; significance levels; measures of HIV risk, mental health conditions and measures; funding source; and study limitations. To assess study quality, we extracted data on study design, sampling strategy, sample size, and participant characteristics, presented in Table 1. These factors were then considered in relation to study quality as presented in the results and discussion. We did not conduct meta-analysis due to the diversity of populations, study designs, and measured outcomes.

Results

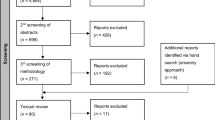

Of 714 citations identified through the search strategy, 33 publications were included in this review (Tables 1 and 2). Figure 1 presents a flowchart of the search and screening process. Eighteen articles were identified via database searching, thirteen through reference searching, and two through searching journal table of contents.

Table 1 provides information on location, study design, sampling strategy, study size, and participant characteristics for each included article. Although most studies were cross-sectional, many articles presented the expected directionality of the relationship based on which variable was considered the exposure and which was considered the outcome. Results are organized by the outcome variable reported by the authors (using the authors’ expected directionality of the association) as follows: mental health and HIV serostatus/HIV-related outcomes; sexual violence and mental health outcomes; HIV acquisition/disease progression and mental health outcomes; and other associations. Under other associations, we include studies that met the inclusion criteria but that did not specify the expected directionality of the associations. Twenty-five studies were from sub-Saharan Africa, five were from the United States of America (USA), and one each was from the Middle East, Europe, and Latin America. Most studies were cross-sectional, though three time-series studies and seven cohort studies reported longitudinal data. Most studies had non-random sampling of participants, though 14 studies utilized a form of random sampling. Overall, 110,818 participants were included across articles. However, there was overlap in participants across four papers discussing child soldiers in Sierra Leone [22,23,24,25], in five papers discussing HIV-positive and negative women, half of whom survived rape during the genocide in Rwanda [26,27,28,29,30], in two papers from Uganda [31, 32], and in two papers from the Wayo-Nero Study in Uganda [33, 34]. The smallest study included 120 participants and the largest study included 71,504 participants.

Table 2 presents each of the included studies by author and year, country, mental health disorders and measurement scales, HIV risk measures, and the relationship found between mental health and HIV-related outcomes. Most studies reported mental health outcomes either in relation to sexual violence or other factors related to HIV acquisition and disease progression. Eight studies reported HIV serostatus or HIV risk outcomes. Three studies reported other outcomes but included analyses of the association between mental health and HIV acquisition and disease progression. In several studies, the relationship between HIV-related factors with mental health was not the main objective, but rather one of many results reported.

Mental health and HIV serostatus/HIV-related outcomes

Of the eight studies that reported HIV serostatus or HIV-related outcomes, five included HIV sexual risk behaviors, two reported HIV serostatus, two reported other STIs, and one reported intimate partner sexual violence.

Four HIV sexual risk behavior studies found some relationship between mental health and HIV risk behaviors. A study from Uganda found a relationship between depression and at least one of eight sexual risk behaviors amongst males in multivariate analysis in a war-affected community (odds ratio (OR) = 1.70, p = 0.05) [32]. In one Rwandan study, increased symptoms of PTSD were correlated with at least one of three HIV risk-taking behaviors (r = 0.24, p = 0.0006) [35]. In another Rwandan study, women who had exchanged sex had greater odds of depression (OR = 1.74, confidence interval (CI) 1.10, 2.76) and PTSD (OR = 1.68, CI 1.19, 2.36) [30]. Women who used condoms at least 50% of the time had decreased odds of PTSD (OR = 0.60, CI 0.42, 0.86), but increased odds of elevated depression scores (OR = 1.84, CI 1.20, 2.82) [30]. Women who had sex in the last six months had decreased odds of depression (OR = 0.57, CI 0.04, 0.81) [30]. A longitudinal study from the USA showed that PTSD predicted unprotected sex four months later (OR = 1.57, CI 1.20, 2.04) [36]. In Lebanon, no relationship was found between PTSD and risky sexual activities [37].

Two studies focused on HIV serostatus as an outcome. Depression (p < 0.001) but not PTSD (p = 0.06) was related to HIV positive serostatus among female survivors of the Rwandan genocide in a cross-sectional, non-randomly selected cohort [30]. In a randomly selected cross-sectional study in Uganda, men and women with depression (adjusted odds ratio (AOR) = 1.89, CI 1.28, 2.80) and PTSD (AOR = 1.44, CI 1.06, 1.96) had greater odds of testing positive for HIV [38].

Two studies reported STIs other than HIV as an outcome. Female survivors of the Rwandan genocide who had a non-HIV STI had greater odds of elevated depression scores (AOR = 1.64, CI 1.01, 2.65), but not PTSD (OR = 1.07, CI 0.77, 1.50) [30]. Female USA veterans of conflict in Iraq and Afghanistan who had PTSD were significantly more likely to have six of seven different STIs compared to veterans without any mental health diagnosis; female veterans with depression were more likely to have all seven STIs compared to those without any mental health diagnosis [39]. Those with comorbid depression and PTSD were even more likely to have all seven STIs compared to those without any mental health diagnosis with adjusted OR between 2.55 and 4.74. This study had the largest population amongst the included articles (N = 71,504) and represented the entire population of female veterans who met inclusion criteria.

Finally, one study from Uganda reported intimate partner sexual violence as an outcome. In this a cross-sectional study, females who experienced sexual violence from an intimate partner had greater odds of probable depression (AOR = 4.20, CI 1.54, 11.46) [31].

Overall, studies reported strong associations between depression and PTSD and HIV serostatus/HIV-related outcomes in African and American conflict-affected populations.

Sexual violence and mental health outcomes

Twenty-two studies reported mental health outcomes: two reported depression only; six PTSD only; six depression and anxiety; six depression and PTSD; and two depression, anxiety, and PTSD. A large number of studies in this review (n = 16) were conducted in sub-Saharan Africa and reported the relationship between mental health and sexual violence, rape, or sexual abuse (as an HIV-related measure out of the victims’ control). The remaining studies in this category were conducted in the USA (n = 3), with Kosovar ethnic Albanians (n = 1), and with Guatemalan refugees in Mexico (n = 1).

Most studies found a positive association between sexual violence and poor mental health; three studies found no association. Sexual abuse predicted depression and anxiety for female Ugandan youth (β = 0.32, p < 0.001) [40]. Experiencing sexual violence was related to PTSD in a study among Ugandan adults (β = 3.75, p < 0.05) [41]. Similarly, in another study of Ugandan adults, those who experienced three or more sexual trauma events had greater odds of PTSD (AOR = 2.02, CI 1.08, 3.67) [34]. For Ugandan adults living in camps for internally displaced people, those who reported rape had greater odds of PTSD (AOR = 1.76, CI 1.01, 2.75), but not depression [42]. Amongst adult and adolescent Guatemalan refugees in Mexico, sexual abuse was independently associated with anxiety, but did not remain significant after controlling for other variables [43]. Among Kosovar ethnic Albanian women, rape was not related to PTSD (AOR = 1.68, CI 0.69, 4.08) [44]. It is notable that in this study, rape was only identified in 4.4% of women (N = 60), [44].

Three studies by the same study team examined the relationship of sexual violence with depression and PTSD in different countries. The studies utilized different methodologies and had different outcomes. Sexual violence was related to PTSD and depression in Liberian adults, with prevalence of PTSD higher for male (81% vs. 46%, p < 0.001) and female (74% vs. 44%, p = 0.005) former combatants who experienced sexual violence; depression was higher for male former combatants who experienced sexual violence compared to those who did not (64% vs.42%, p = 0.003) [45]. In the Democratic Republic of Congo, prevalence of PTSD (70.2% vs. 40.3%, p < 0.001) and depression (60.4% vs. 30.7%, p < 0.001) were higher for participants who experienced sexual violence compared to those who did not; prevalence of PTSD and depression were higher for females who experienced conflict-related sexual violence compared to females who did not, respectively (75.9% vs. 44.4%, p < 0.001 and 67.7% vs. 30.3%, p < 0.001) [46]. During the 2007 election violence in Kenya, the prevalence of sexual violence was not significantly related to major depressive disorder or PTSD [47].

The Liberian study had the strongest methodological quality (utilizing a population based multistage random household cluster survey) and the study in the Democratic Republic of Congo had the weakest quality of the three (non random accessible population cluster). Although sexual violence in Kenya was not significantly related to major depressive disorder and PTSD, sexual violence was significantly related to suicidal ideation and suicide attempt [47].

Sexual torture and being forced to marry were not related to depression, anxiety, and PTSD amongst formerly war abducted adolescents in Uganda [48]. However, the study may not have had the statistical power to detect significance for such analysis as the primary objective was to compare formerly abducted and non-abducted adolescents. No trauma event had a significant relationship with mental health outcomes in this randomly selected population.

Four studies reported data from a non-randomly selected prospective cohort of child soldiers in Sierra Leone. In two studies with overlapping samples (one cross-sectional with 273 participants and one longitudinal with 156 participants), rape was significantly related to anxiety (b = 2.85, p = 0.05; b = 4.06, p < 0.05), especially in males, but not depression after controlling for other variables [23, 24]. In a slightly different sample, rape was associated with increased anxiety after controlling for discrimination and protective factors (b = 5.35, p < 0.001); rape significantly predicted an increase in depression over time, but this relationship lessened when perceived discrimination was added and was no longer significant when protective factors were added [22]. Rape was the only time-invariant predictor found to be related to depression/anxiety (considered together) after adjusting for hardship and protective factors (b = 4.34, p = 0.04) [25]. Combined, these studies demonstrate that rape (as a more extreme war event) is a strong predictor of anxiety over time amongst war-affected adolescents.

Three publications examined sexual assault and mental health in conflict-affected American military populations. Female veterans who returned from deployment in the Persian Gulf were more likely to experience PTSD if they had been sexually assaulted during their service compared to women who did not experience harassment, who only experienced verbal harassment, and who experienced physical harassment that was not sexual assault [49]. In cross-sectional analyses, female veterans with PTSD compared to those without PTSD were more likely to have experienced sexual assault while in the military (43% vs. 5.1%, p < 0.001) [50]. Sexual assault reports were significantly associated with PTSD for men (OR = 6.21, CI 2.26, 17.04) and women (OR = 5.41, CI 3.19, 9.17) after controlling for other variables [51]. Findings from these studies supported a relationship between sexual assault and poor mental health.

Overall, studies reported strong associations between sexual violence and all three mental health outcomes. Sexual violence was most strongly associated with PTSD [41, 42, 45, 46, 49,50,51], then depression [22, 24, 25, 40, 45, 46], and then anxiety mainly amongst male survivors [22,23,24,25, 40, 43].

HIV acquisition/disease progression and mental health outcomes

Factors related to HIV acquisition and disease progression were associated with mental health outcomes in two studies that reported HIV sexual risk behavior, one that reported CD4 count, one that reported receiving HIV treatment, two that reported HIV status, and two that compared HIV-positive and HIV-negative participants and rape during genocide.

In Uganda, formerly conflict-abducted young women who recently exchanged sex for money or resources were assessed for mental health with a locally developed measure; mean depression and anxiety scores were 12.84 and 8.76, respectively [52]. Cut off scores defining symptomatic versus asymptomatic depression and anxiety were not provided in this study so no conclusion can be made regarding the association between HIV sexual risk with depression and anxiety. In another study in Uganda, adults with high risk sexual behavior did not have higher odds of depression (AOR = 1.37, CI 0.91, 2.09) [33].

Lower CD4 count indicates more advanced HIV disease progression and potentially increases transmissibility. In one non-randomly selected population in Rwanda, there was no difference in depression scores for adults with CD4 counts at or below 200 compared to adults with CD4 counts over 200 [53]. Receiving HIV treatment was associated with depression (AOR = 3.22, CI 1.08, 9.57) among a random selection of adults in Uganda [33]. Reporting an HIV-positive status was associated with both PTSD (OR = 2.09, CI 1.48, 2.95) [34] and depression (OR = 1.83, CI 1.22, 2.74) [33] among Ugandan adults.

In two publications from another non-randomly selected cohort in Rwanda, depression and PTSD in HIV-positive and negative women were examined both cross-sectionally and longitudinally. At baseline, HIV-positive women were more likely than HIV-negative women to have depression symptoms (81% vs. 65%, p < 0.0001) and HIV-positive women with CD4 counts below 200 were the most likely to have depression symptoms (OR = 4.97, CI 2.93, 8.45) [26]. Women who experienced rape during the genocide were more likely to have PTSD (OR = 1.63, CI 1.23, 2.15) and depression (OR = 1.56, CI 1.12, 2.16) in unadjusted analysis [26]. Over three follow-up visits at six, twelve, and eighteen months, HIV-positive and HIV-negative women had reduced PTSD scores; this improvement was not related to antiretroviral therapy (ART) use, but was related to HIV-positive status at follow-up three, and was related to rape during the genocide at follow-ups two and three [27]. Overall, studies examining mental health outcomes and factors related to HIV acquisition and disease progression reported both positive and null associations.

Other associations between mental health and HIV acquisition and disease progression

Three studies used other outcomes for their primary analyses but provided data assessing the cross-sectional association between mental health and HIV acquisition and disease progression, making less clear the authors’ expected directionality of the relationship. One study in Rwanda (with some study population overlap with other included articles) examined quality of life amongst trauma-affected women with and without HIV. About half of the women in each group had experienced rape during the genocide. HIV-positive women experienced increased depression symptom scores compared to HIV-negative women (p < 0.001), but a greater percentage of HIV-negative women experienced elevated symptoms of PTSD [28]. In another study in Rwanda among HIV positive women (with study population overlap) depression (p < 0.001), but not PTSD (p = 0.60), was associated with CD4 count [29]. In the Democratic Republic of Congo, family rejection amongst survivors of sexual assault was more strongly related to depression, but increased PTSD was more strongly related to sexual assault [54]. Rape or sexual assault in the past ten years was associated with both increased PTSD (β = 0.35, p < 0.001) and depression (β = 0.29, p < 0.001).

Overall, studies in this category demonstrated inconsistent associations between mental health and HIV acquisition and disease progression.

Discussion

Overall, the thirty-three studies included in this review suggest that symptoms of poor mental health are associated with increased sexual risk behaviors and HIV markers, and HIV exposures and HIV-related health status are associated with poor mental health symptoms in conflict-affected populations. Only five studies found no association between mental health and factors related to HIV acquisition and disease progression. Associations were strongest for mental health and HIV serostatus/HIV-related outcomes and sexual violence and mental health outcomes. Associations between HIV acquisition/disease progression and mental health outcomes and outcomes that examined other associations were more inconsistent. This could be partially attributed to the greater variety in the types of associations measured in these categories. For example, studies that examined sexual violence and mental health outcomes only included associations between sexual violence and mental health, given the large number of studies in this category. However, studies that examined HIV acquisition/disease progression and mental health outcomes looked at a variety of HIV-related correlates with mental health outcomes (e.g. CD4 count, sexual risk behaviors, HIV positive serostatus).

There were slight inconsistencies across studies in associations. For articles that found an association between one or more mental health disorders and factors related to HIV acquisition and disease progression, there were other articles, or findings within the same article, that failed to identify a relationship with one or more other disorders. These inconsistencies may represent real differences in various associations or populations. Inconsistencies in the findings may also be attributed to less rigor among some studies that did not find associations: non-random selection and small sample size [37], small numbers of relevant participants within the sample [43, 48], and low rates of the HIV-related variable [35]. Some studies that did not find associations had trends towards an association [47] or a marginal association [31]. Studies with strong rigor (large sample sizes of randomly selected participants or the entire population) found strong positive associations both in conflict-affected USA [39, 50, 51] and African populations [31, 38].

Our findings are similar to a review of HIV risk behaviors and trauma amongst migrants from low and middle-income countries [18]. Our study differs from the review by Michalopoulos et al. by including associations between mental health and factors related to HIV acquisition and disease progression in conflict-affected populations from high-income countries, focusing on measurable mental health disorders, and exclusively presenting quantitative relationships.

We only included mental health symptoms documented by validated scales to ensure that included studies met a minimal level of measurement rigor and to increase comparability of findings across studies. Most included articles meet the criteria for ‘protracted’ or ‘post-conflict’ [21, 47]. However, one study stands out as it specified reporting election-related violence rather than war or conflict; with 1133 deaths over 59 days, the setting met criteria for an ‘explosive’ event [21, 47]. This demonstrates the range of included conflict-affected settings. Because HIV disproportionally affects sub-Saharan Africa, much of the literature discussing conflict and HIV focuses on this geographic area. Similarly, a wide range of conflict-affected populations were included in this review, from soldiers fighting in their own country to returned American combat veterans, from orphans to child soldiers, from abducted civilians to those living in internally displaced persons camps. Unfortunately, there were not enough studies examining the same factors in the range of conflict-affected regions or populations to draw strong conclusions as to how these relationships might differ by region or population.

We used findings from this review along with existing literature to develop a framework (Fig. 2). Mock et al. described how HIV prevalence could increase (via increased military and civilian interaction, increased commercial and casual sex, etc.) or decrease (via increased isolation, mortality of high-risk populations, etc.) in conflict-affected settings [13]. It is well established in the literature that conflict-affected populations are at risk for poor mental health [8, 12, 55], and often lack access to mental health services [56, 57]. Physiological, psychological, and social pathways can influence the relationship between HIV-related outcomes and mental health disorders [7]. What is lacking in the literature, to the best of our knowledge, is a framework that incorporates the relationship between mental health and factors associated with HIV acquisition and progression in conflict-affected populations.

Relationship Between Mental Health & HIV in Conflict Settings. This figure illustrates a framework of the relationship between mental health and HIV serostatus and HIV-related outcomes among conflict-affected populations, based on this review and existing literature. The outside blue panel presents existing knowledge of factors in conflict-affected settings. HIV prevalence could increase or decrease in conflict-settings through various mechanisms [13]. Multiple factors contribute to increased risk for poor mental health in conflict-affected settings. Additional factors adversely affect conflict-affected populations. The inside box presents the relationship between mental health and HIV-related outcomes. HIV can physiologically, psychologically, and socially increase risk for mental health disorders. Health status (being HIV-positive and lower CD4 count) is associated with poor mental health. Poor mental health can influence HIV risk exposures (sexual risk behaviors and STIs). Surviving sexual assault is associated with poor mental health and HIV-related outcomes. Demographic factors can influence each relationship

Our findings provide evidence for this framework. Specifically, we identified studies that demonstrate health status (HIV-positive serostatus, lower CD4 count) is associated with increased depression [26,27,28,29,30, 38], that mental health disorders may influence HIV risk exposures (sexual risk behaviors [30, 32, 36] and STIs [30, 39]), and that surviving sexual assault may be associated with poor mental health [22,23,24,25, 40, 41, 43, 45, 46, 49,50,51].

There were several limitations to this review. First, only one reviewer identified, screened, and extracted data from included studies. Methodological rigor would be strengthened if two reviewers had independently completed each step and resolved any discrepancies. Although it was not possible to have two reviewers conduct all steps in the review process, a second, experienced reviewer was consulted when specific questions arose during the process and a third reviewer verified the extracted data. Second, the search terms for ‘conflict’ focused only on conflict and war. By excluding terms such as refugee, displaced persons, and asylum seekers we may have missed articles relevant to this review.

We examined only three mental health disorders, selected because they are common and frequently measured in conflict-affected populations. However, other disorders may be relevant in conflict-affected populations, specifically substance use, which has been shown to be common, harmful, and related to HIV transmission and risk in conflict-affected populations [58,59,60]. Finally, 23 of the 33 studies were cross-sectional, so the temporality of these relationships cannot be determined. No studies were identified in this review that examined the association between viral suppression and mental health; future studies should examine these associations. Longitudinal studies should also be conducted examining associations between mental health and factors related to HIV acquisition and disease progression. Future reviews could examine the associations between HIV acquisition or risk behaviors and substance use or other mental health disorders in conflict-affected populations.

There are several implications from this review. Considering the associations discussed in this paper, programs delivering HIV or other reproductive health services for conflict-affected populations should consider screening individuals who have HIV or STIs for mental health disorders using appropriate cross-culturally validated tools. Referrals could then be made, assuming availability of evidence-based interventions. Similarly, programs delivering mental health services should consider screening for HIV serostatus and associated risk factors. Since health infrastructure is often limited in conflict-affected settings, combining screening and services offers the potential to more systematically and holistically treat vulnerable individuals. An example where this has occurred is in Uganda, where an organization that provided mental health interventions for conflict survivors included HIV screening, referrals, and services to meet the unique mental health needs of people living with HIV [61].

At the policy level, by recognizing the relationships between mental health and factors related to HIV acquisition and disease progression in conflict settings, infrastructure can be integrated to offer mental health and HIV-related services simultaneously. Policy could also require monitoring of results to recognize any differences in separate treatment compared to integrated treatment of mental health and HIV-related services. Future research should employ stronger methods where possible – specifically, random selection of participants to decrease bias and longitudinal studies to better determine directionality of the measured associations. Research should also examine the associations of mental health with HIV acquisition and disease progression with a wider range of conflict-affected populations, as the relationship may vary depending on the population and the possibilities for risk exposure.

Conclusions

Existing literature demonstrates that depression, anxiety, and PTSD have been quantifiably associated with four factors related to HIV acquisition and disease progression in conflict-affected populations: markers of HIV risk (i.e. STIs), HIV-related health status (e.g. CD4 count), sexual risk behaviors, and HIV risk exposures (i.e. sexual violence). Specifically, poor mental health has been associated with two outcomes, HIV markers and sexual risk behaviors, while HIV risk exposures and health status have been associated with the outcome of poor mental health. Additional research utilizing random selection and longitudinal design can further establish the strength of these associations and determine if HIV and mental health services need to be integrated for conflict-affected populations.

Abbreviations

- AOR:

-

Adjusted Odds Ratio

- ART:

-

Antiretroviral Therapy

- CI:

-

Confidence Interval

- HIV:

-

Human Immunodeficiency Virus

- HTQ:

-

Harvard Trauma Questionnaire

- IDP:

-

Internally Displaced Person

- MDD:

-

Major Depressive Disorder

- OR:

-

Odds Ratio

- PTSD:

-

Posttraumatic Stress Disorder

- SD:

-

Standard Deviation

- SE:

-

Standard Error

- STI:

-

Sexually Transmitted Infection

- UNESCO:

-

United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organization

- USA:

-

United States of America

References

Nduna M, et al. Associations between depressive symptoms, sexual behaviour and relationship characteristics: a prospective cohort study of young women and men in the eastern cape, South Africa. J Int AIDS Soc. 2010;13(1):1.

Agardh A, Cantor-Graae E, Östergren PO. Youth, sexual risk-taking behavior, and mental health: a study of university students in Uganda. International journal of behavioral medicine. 2012;19(2):208–16.

Cavanaugh CE, Hansen NB, Sullivan TP. HIV sexual risk behavior among low-income women experiencing intimate partner violence: the role of posttraumatic stress disorder. AIDS Behav. 2010;14(2):318–27.

Hutton HE, et al. HIV risk behaviors and their relationship to posttraumatic stress disorder among women prisoners. Psychiatr Serv. 2001;52(4):508–13.

Munroe CD, et al. The relationship between posttraumatic stress symptoms and sexual risk: examining potential mechanisms. Psychological Trauma: Theory, Research, Practice, and Policy. 2010;2(1):49.

Rubin A, Gold M, Primack BA. Associations between depressive symptoms and sexual risk behavior in a diverse sample of female adolescents. J Pediatr Adolesc Gynecol. 2009;22(5):306–12.

Prince M, et al. No health without mental health. Lancet. 2007;370(9590):859–77.

De Jong JTVM, et al. Lifetime events and posttraumatic stress disorder in 4 postconflict settings. JAMA. 2001;286(5):555–62.

Hamid AARM, Musa SA. Mental health problems among internally displaced persons in Darfur. Int J Psychol. 2010;45(4):278–85.

Kamau M, et al. Psychiatric disorders in an African refugee camp. International Journal of Mental health, Psychosocial Work and Counselling in Areas of Armed Conflict. 2004;2(2):84–9.

Srinivasa Murthy R. Mass violence and mental health--recent epidemiological findings. Int Rev Psychiatry. 2007;19(3):183–92.

Steel Z, et al. Association of torture and other potentially traumatic events with mental health outcomes among populations exposed to mass conflict and displacement: a systematic review and meta-analysis. JAMA. 2009;302(5):537–49.

Mock NB, et al. Conflict and HIV: a framework for risk assessment to prevent HIV in conflict-affected settings in Africa. Emerg Themes Epidemiol. 2004;1(1):1.

Salama P, Dondero TJ. HIV surveillance in complex emergencies. AIDS. 2001;15:S4–S12.

Spiegel PB, et al. Prevalence of HIV infection in conflict-affected and displaced people in seven sub-Saharan African countries: a systematic review. Lancet. 2007;369(9580):2187–95.

Bennett BW, et al. Hiv incidence prior to, during, and after violent conflict in 36 sub-Saharan african nations, 1990-2012: an ecological study. PLoS One. 2015;10(11):e0142343.

Mulanga C, et al. Political and socioeconomic instability: how does it affect HIV? A case study in the Democratic Republic of Congo. AIDS. 2004;18(5):832–4.

Michalopoulos LM, Aifah A, El-Bassel N. A systematic review of HIV risk behaviors and trauma among forced and unforced migrant populations from low and middle-income countries: state of the literature and future directions. AIDS Behav. 2015:1–19.

Collins PY, et al. What is the relevance of mental health to HIV/AIDS care and treatment programs in developing countries? A systematic review. AIDS. 2006;20(12):1571.

Moher D, et al. Preferred reporting items for systematic reviews and meta-analyses: the PRISMA statement. Ann Intern Med. 2009;151(4):264–9.

Strand, H. and M. Dahl, Defining Conlict-affected Countries. 2010: Unesco.

Betancourt TS, et al. Past horrors, present struggles: the role of stigma in the association between war experiences and psychosocial adjustment among former child soldiers in Sierra Leone. Soc Sci Med. 2010;70(1):17–26.

Betancourt TS, et al. Sierra Leone's child soldiers: war exposures and mental health problems by gender. J Adolesc Health. 2011;49(1):21–8.

Betancourt TS, et al. Sierra Leone’s former child soldiers: a follow-up study of psychosocial adjustment and community reintegration. Child Dev. 2010;81(4):1077–95.

Betancourt TS, et al. Sierra Leone's former child soldiers: a longitudinal study of risk, protective factors, and mental health. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 2010;49(6):606–15.

Cohen MH, et al. Prevalence and predictors of posttraumatic stress disorder and depression in HIV-infected and at-risk Rwandan women. J Women's Health (Larchmt). 2009;18(11):1783–91.

Cohen MH, et al. Improvement in posttraumatic stress disorder in postconflict Rwandan women. J Women's Health (Larchmt). 2011;20(9):1325–32.

Gard TL, et al. The impact of HIV status, HIV disease progression, and post-traumatic stress symptoms on the health-related quality of life of Rwandan women genocide survivors. Qual Life Res. 2013;22(8):2073–84.

Sinayobye JdA, et al. Prevalence of shingles and its association with PTSD among HIV-infected women in Rwanda. BMJ Open. 2015;5(3):e005506.

Adedimeji AA, et al. Sexual behavior and risk practices of HIV positive and HIV negative Rwandan women. AIDS Behav. 2015;19(7):1366–78.

Kinyanda E, et al. Intimate partner violence as seen in post-conflict eastern Uganda: prevalence, risk factors and mental health consequences. BMC Int Health Hum Rights. 2016;16(1):5.

Kinyanda E, et al. Psychiatric disorders and psychosocial correlates of high HIV risk sexual behaviour in war-affected eastern Uganda. AIDS Care. 2012;24(11):1323–32.

Mugisha J, et al. Major depressive disorder seven years after the conflict in northern Uganda: burden, risk factors and impact on outcomes (the Wayo-Nero study). BMC psychiatry. 2015;15(1):48.

Mugisha J, et al. Prevalence and factors associated with posttraumatic stress disorder seven years after the conflict in three districts in northern Uganda (the Wayo-Nero study). BMC psychiatry. 2015;15(1):170.

Talbot A, et al. Treating psychological trauma among Rwandan orphans is associated with a reduction in HIV risk-taking behaviors: a pilot study. AIDS Educ Prev. 2013;25(6):468–79.

Adler AB, et al. Effect of transition home from combat on risk-taking and health-related behaviors. J Trauma Stress. 2011;24(4):381–9.

Svetlicky V, et al. Combat exposure, posttraumatic stress symptoms and risk-taking behavior in veterans of the second Lebanon war. Isr J Psychiatry Relat Sci. 2010;47(4):276–83.

Malamba SS, et al. “The Cango Lyec Project-Healing the Elephant”: HIV related vulnerabilities of post-conflict affected populations aged 13–49 years living in three Mid-Northern Uganda districts. BMC Infect Dis. 2016;16(1):690.

Cohen BE, et al. Reproductive and other health outcomes in Iraq and Afghanistan women veterans using VA health care: association with mental health diagnoses. Womens Health Issues. 2012;22(5):e461–71.

Amone-P’Olak K, et al. Cohort profile: mental health following extreme trauma in a northern Ugandan cohort of war-affected youth study (the WAYS study). SpringerPlus. 2013;2(1):1–11.

Nakimuli-Mpungu E, et al. Implementation and scale-up of psycho-trauma centers in a post-conflict area: a case study of a private-public Partnership in Northern Uganda. PLoS Med. 2013;10(4)

Roberts B, et al. Factors associated with post-traumatic stress disorder and depression amongst internally displaced persons in northern Uganda. BMC psychiatry. 2008;8(1):38.

Sabin M, et al. Factors associated with poor mental health among Guatemalan refugees living in Mexico 20 years after civil conflict. JAMA. 2003;290(5):635–42.

Cardozo BL, et al. Mental health, social functioning, and attitudes of Kosovar Albanians following the war in Kosovo. JAMA. 2000;284(5):569–77.

Johnson K, et al. Association of combatant status and sexual violence with health and mental health outcomes in postconflict Liberia. JAMA. 2008;300(6):676–90.

Johnson K, et al. Association of sexual violence and human rights violations with physical and mental health in territories of the eastern Democratic Republic of the Congo. JAMA. 2010;304(5):553–62.

Johnson K, et al. A national population-based assessment of 2007–2008 election-related violence in Kenya. Confl Health. 2014;8:2.

Okello J, Onen T, Misisi S. Psychiatric disorders among war-abducted and non-abducted adolescents in Gulu district, Uganda: a comparative study. Afr J Psychiatry (Johannesbg). 2007;10(4):225–31.

Wolfe J, et al. Sexual harassment and assault as predictors of PTSD symptomatology among US female Persian gulf war military personnel. Journal of Interpersonal Violence. 1998;13(1):40–57.

Washington DL, et al. PTSD risk and mental health care engagement in a multi-war era community sample of women veterans. JGIM: Journal of General Internal Medicine. 2013;28(7):894–900.

Kang H, et al. The role of sexual assault on the risk of PTSD among gulf war veterans. Ann Epidemiol. 2005;15(3):191–5.

Muldoon KA, et al. After abduction: exploring access to reintegration programs and mental health status among young female abductees in northern Uganda. Confl Health. 2014;8:5.

Epino HM, et al. Reliability and construct validity of three health-related self-report scales in HIV-positive adults in rural Rwanda. AIDS Care. 2012;24(12):1576–83.

Kohli A, et al. Risk for family rejection and associated mental health outcomes among conflict-affected adult women living in rural eastern Democratic Republic of the Congo. Health Care for Women International. 2014;35(7–9):789–807.

Miller KE, Andrew R. War exposure, daily stressors, and mental health in conflict and post-conflict settings: bridging the divide between trauma-focused and psychosocial frameworks. Soc Sci Med. 2010;70(1):7–16.

Mollica RF, et al. Mental health in complex emergencies. Lancet. 2004;364(9450):2058–67.

Tol WA, et al. Mental health and psychosocial support in humanitarian settings: linking practice and research. Lancet. 2011;378(9802):1581–91.

Ezard N. Substance use among populations displaced by conflict: a literature review. Disasters. 2012;36(3):533–57.

Ezard N, et al. Six rapid assessments of alcohol and other substance use in populations displaced by conflict. Confl Health. 2011;5(1):1.

Friedman SR, Rossi D, Braine N. Theorizing 'Big Events' as a potential risk environment for drug use, drug-related harm and HIV epidemic outbreaks. International Journal of Drug Policy. 2009;20(3):283–91.

Sharer, M. and M. Gutmann, Prioritizing HIV in mental health services delivered in post-conflict settings. 2011.

Acknowledgements

The authors thank Peggy Gross for assistance with generating the search terms. We also thank David Celentano for his extensive feedback on an earlier draft and Jessica Haslag for verifying the extracted data.

Funding

This research was supported by NIMH NRSA F31MH095678.

Availability of data and materials

The data extracted from each included article is available upon request.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

EK extracted the data, coded included articles, analyzed the data, and was the primary writer of the manuscript. CK provided substantial contributions to the design of the study, analysis and interpretation of the data, and provided critical revisions throughout several drafts of the manuscript. Both authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

Not applicable

Consent for publication

Not applicable

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Additional file

Additional file 1:

Scoping review search terms for PubMed. (DOCX 14 kb)

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made. The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver (http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/) applies to the data made available in this article, unless otherwise stated.

About this article

Cite this article

Koegler, E., Kennedy, C.E. A scoping review of the associations between mental health and factors related to HIV acquisition and disease progression in conflict-affected populations. Confl Health 12, 20 (2018). https://doi.org/10.1186/s13031-018-0156-y

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s13031-018-0156-y