Abstract

Background

Family members of patients with eating disorders, especially their mothers, experience heavy caregiving burdens associated with supporting the patient. We predict that increasing caregivers’ support will have a positive effect on their active listening attitudes, mental health, loneliness, and self-efficacy. This study aimed to investigate differences in mothers’ active listening attitudes, mental health, loneliness, and self-efficacy improvements between mothers who did and did not experience increased perceived social support.

Main body

Participants were mothers of patients with eating disorders. Questionnaires for this cohort study were sent to the participants’ homes at three time points (baseline, 9 months, and 18 months). The Japanese version of the Social Provision Scale (SPS-10) was used to evaluate social support, the Active Listening Attitude Scale (ALAS) for listening attitude, the UCLA Loneliness Scale (ULS) for loneliness, the General Self-Efficacy Scale (GSES) for self-efficacy, the Beck Depression Inventory (BDI-II) for depression symptoms, and the K6 for psychological distress. An unpaired t-test was used to determine whether participants’ status differed between the groups that did and did not experience increased perceived social support. The mean age of the participants was 55.1 ± 6.7 (mean ± SD) years. The duration of their children’s eating disorders was 7.6 ± 5.5 years. The degree of improvement for each variable (active listening attitude, loneliness, self-efficacy, depressive symptoms, and mental health) was the difference in each score (ALAS, ULS, GSES, BDI-II, and K6) from T1 to T3. The degree of improvement in active listening attitude and loneliness was significantly greater in the improved social support group than in the non-improved social support group (p < 0.002 and p < 0.012, respectively).

Conclusions

Our findings indicate that increasing mothers’ perceptions of social support will be associated with improving their active listening attitudes and loneliness.

Similar content being viewed by others

Background

Eating disorders are serious mental disorders associated with high levels of mortality and disability, physical and psychological morbidity, and impaired quality of life. The estimated standardized mortality ratios are 5.86 for anorexia nervosa (AN), 1.7 for bulimia nervosa, and 1.92 for eating disorders not otherwise specified [1]. Evidence of effective treatments for eating disorders in children and adolescents has been established [2]. However, a network meta-analysis of psychological interventions in adult AN outpatients reported no strong evidence to support the superiority or inferiority of any of the specific treatments recommended by clinical guidelines [3]. Even if there are evidence-based treatments for child and adolescent eating disorders, it is difficult to provide them to everyone who needs them.

With few effective treatments available, many families live with individuals with eating disorders who often engage in problematic behaviors such as suicidal behavior, obsessional thoughts, refusal of treatment, and behaviors concerning weight, body shape, and food for extended periods of time [4]. Family members who spend much of their time with the patient, especially mothers, suffer a heavy psychological burden. Although some studies have reported that caregivers do not experience high levels of distress, many studies have suggested that they experience high levels of depression and anxiety [5, 6].

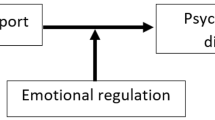

Patients with eating disorders have been found to lack confidence in identifying their thoughts and feelings [7, 8]. Submissive behavior was significantly higher in patients with eating disorders than in healthy controls [9]. Some studies have identified a strong relationship between low levels of assertiveness and eating disorder psychopathology [10, 11]. It is believed that patients with eating disorders are unable to recognize and assert their thoughts and desires. Mothers’ good active listening ability may promote self-expression in patients with these characteristics. However, as mentioned above, mothers often experience high distress owing to the difficulty of responding to various symptoms and their involvement in eating disorder behaviors. Such situations make it difficult for mothers to relax and listen to patients well. Several studies have reported that caregiver support is associated with psychosocial stress and coping. Perceived high social support has been significantly associated with lower levels of depression among mothers of patients with eating disorders [12]. Some studies have reported that social support increases caregivers’ ability to cope [13, 14].

This cohort study aimed to investigate differences in mothers’ active listening attitudes, mental health, loneliness, and self-efficacy improvements between mothers who did and did not experience increased perceived social support.

Methods

Design

This was a longitudinal survey with assessments at three time points: baseline (Time 1 [T1]), 9 months (Time 2 [T2]), and 18 months (Time 3 [T3]).

Participants

Participants were mothers of patients with eating disorders. Inclusion criteria were age between 30 and 85 years and being the mother of a child who met the patient inclusion criteria. The inclusion criteria for patients were age between 16 and 50 years and a clinical diagnosis of an eating disorder from a physician or psychiatrist in a hospital. Regarding caregivers, although we understand the fathers’ involvement is important for the treatment of eating disorders, this study focuses only mothers to ensure the homogeneity of the participants because it has been reported that mothers have a higher burden than fathers [15]. To recruit participants, we conducted lectures at four locations in Japan (i.e., Hokkaido, Chiba, Fukui, and Nagoya). These lectures included an introduction to the study. Participants were recruited between July 2017 and August 2018, with the last follow up in February 2020. Participants were provided with a leaflet explaining the study’s purpose and procedures. After receiving permission, we mailed the questionnaires to the participants’ homes. Participants were formally enrolled in the study only when their completed baseline questionnaires were returned. The questionnaires were mailed at three time points (i.e., at baseline, 9 months, and 18 months) and returned each time. The scales completed at each time point were the same. This study was approved by the Ethics Review Committee of Nagoya City University Graduate School of Medical Sciences, Japan (Ref: No 60–17-0001).

Outcome measures

A shortened version of Social Provisions Scale (SPS-10) by Iapichino et al. was used to evaluate mothers’ perception of social support [16]. We created a Japanese version of the SPS-10 [17]. The SPS-10 consists of 10 items and retains the following five of the six original SPS subscales: attachment, social integration, reassurance of worth, reliable alliance, and guidance. The total SPS-10 score ranges from 10 to 40. A higher score indicates a stronger perception of social support. The General Self-Efficacy Scale (GSES) developed by Sakano et al. was used to assess mothers’ self-efficacy [18]. The higher the score, the higher the general self-efficacy. The Japanese version [19] of the University of California, Los Angeles Loneliness Scale (ULS), originally developed by Russell et al., was used to assess mothers’ loneliness [20]. The higher the score, the stronger the loneliness. The Active Listening Attitude Scale (ALAS) developed by Mishima et al. was used to assess mothers’ active listening attitude [21]. The higher the score, the better the listening attitude or skill. The Japanese version [22] of the Beck Depression Inventory—Second Edition (BDI-II), originally developed by Beck et al., was used to assess depression within the last two weeks [23]. The higher the score, the more severe the depressive symptoms. The Japanese version [24] of the Kessler Psychological Distress Scale (K6), originally developed by Kessler et al., was used to assess psychological distress [25]. The higher the score, the more severe the psychological distress.

Statistical analysis

Descriptive data analysis was conducted by calculating mean scores, standard deviations, or rates (%). Correlations among the variables at T1 were examined using Pearson’s correlation coefficient. We examined changes in status between mothers who did and did not experience increased perceived social support. Mothers who experienced increased perceived social support comprised those whose SPS-10 scores increased from T1 to T3. Mothers who did not experience increased perceived social support consisted of participants whose SPS-10 scores remained the same or decreased from T1 to T3. We used an unpaired t-test to compare the two groups, with significance set at p < 0.05. Statistical analyses were performed using SPSS Statistics version 22.

Results

Participants’ characteristics

We mailed 85 sets of questionnaires to the participants’ homes, 72 of which were returned. The mean age was 55.1 ± 6.7 (mean ± SD) years. The duration for which their children had suffered from an eating disorder was 7.6 ± 5.5 years. Half of the participants cooperated with their partner in caring for the patient, and 68.4% were currently part of a family self-help group. Table 1 summarizes the participants’ baseline (T1) characteristics, and Table 2 summarizes the participants’ scores at all three time points. Correlations among the variables at T1 are summarized in Table 3. There were moderate or strong significant correlations between the scales.

Comparison between the improved social support group and non-improved social support group

The groups of mothers who did and did not experience increased perceived social support consisted of 26 and 38 participants, respectively. The mean age of the participants who experienced increased perceived social support was 54.6 ± 7.2, and their children’s eating disorder duration was 7.5 ± 6.2 years. The mean age of the participants who did not experience increased perceived social support was 55.3 ± 6.0, and their children’s eating disorder duration was 7.6 ± 4.4 years. The degree of improvement for each variable (active listening attitude, loneliness, self-efficacy, depressive symptoms, and mental health) was the difference in each score (ALAS, ULS, GSES, BDI-II, and K6) from T1 to T3. The degree of improvement in active listening attitude and loneliness was significantly greater in the improved social support group than in the non-improved social support group (p < 0.002 and p < 0.012, respectively; Table 4). No significant difference was found between the groups regarding the score differences from T1 to T2 (Table 4).

Discussion

This study investigated differences in active listening attitude, mental health, loneliness, and self-efficacy after 18-months follow-up among mothers who did and did not experience increased perceived social support. Our findings suggest that increasing a mothers’ perceptions of social support may be associated with improving their active listening attitudes and loneliness. Because being a single parent and eating alone have been associated with the onset of eating disorders [26], the parents’ concern and listening to them may be important for eating disorder prevention and recovery.

Patients with eating disorders have been found to lack confidence in identifying their own thoughts and feelings and have low levels of assertiveness [10, 11]; if their mothers consistently listened well, they would be able to explain themselves without anxiety. Marcos reported significant positive correlations between informative support for patients with eating disorders, including listening, encouraging, and advising, and family self-concept as evaluated by the patient [27]. Family self-concept refers to patient-evaluated feelings such as “I feel more or less happy at home” and “parents would help with any type of problem.” Results from the above studies indicate that caregivers who listen and encourage patients help them feel safe and have peace of mind at home. If mothers of patients with eating disorders listen well, patients are able to use verbal communication more frequently; they may be able to avoid using eating disorder behaviors. These findings revealed that increasing mothers’ perceptions of social support may be associated with improving their active listening attitudes.

However, the mothers in this study showed worse mental health status at T1 (Table 2; the average BDI-II score of 14.1 ± 9.2 for our participants indicated mild depressive symptoms). Such mental exhaustion situations make it difficult for mothers to listen to patients. At T1 (Table 3), there were strong significant correlations between SPS-10 and ULS (r =—0.794) and moderate significant correlations between the SPS-10 and K6 (r = -0.407) and the SPS-10 and BDI-II (r = -0.463). These results highlight the importance of continuing support from professionals and self-help groups for the mothers of patients with eating disorders.

This study has several limitations. First, the sample size is small. This may have resulted in the small effects we observed, subsequently preventing the detection of significant differences among the studied variables. Second, we did not identify or differentiate between subgroups of eating disorders. Thus, we believe that future studies should distinguish patients by specific eating disorder; different types may evoke different outcomes among caregivers. However, the strength of our study was its cohort study design using 18-month follow-up data.

Conclusion

Our main findings suggest that social support for mothers of patients with eating disorders is associated with improving their active listening attitudes. Therefore, it is important that professionals and self-help support groups continuously support not only patients with eating disorders but also their caregivers.

Availability of data and materials

The datasets used and/or analyzed in the current study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

Abbreviations

- ALAS:

-

Active Listening Attitude Scale

- BDI-II:

-

Beck Depression Inventory

- CFI:

-

Comparative Fit Index

- GSES:

-

General Self-Efficacy Scale

- K6:

-

Kessler Psychological Distress Scale

- RMSEA:

-

Root Mean Square Error of Approximation

- SEM:

-

Structural Equation Modeling

- SPS:

-

The Social Provisions Scale

- SPS-10:

-

The Social Provisions Scale-10 item

- ULS:

-

University of California, Los Angeles Loneliness Scale

References

Arcelus J, Mitchell AJ, Wales J, Nielsen S. Mortality rates in patients with anorexia nervosa and other eating disorders. a meta-analysis of 36 studies. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2011;68:724–31. https://doi.org/10.1001/archgenpsychiatry.2011.74.

Couturier J, Isserlin L, Norris M, Spettigue W, Brouwers M, Kimber M, McVey G, Webb C, Findlay S, Bhatnagar N, Snelgrove N, Ritsma A, Preskow W, Miller C, Coelho J, Boachie A, Steinegger C, Loewen R, Loewen T, Waite E, Ford C, Bourret K, Gusella J, Geller J, LaFrance A, LeClerc A, Scarborough J, Grewal S, Jericho M, Dimitropoulos G, Pilon D. Canadian practice guidelines for the treatment of children and adolescents with eating disorders. J Eat Disord. 2020;8:4. https://doi.org/10.1186/s40337-020-0277-8.

Solmi M, Wade TD, Byrne S, Del Giovane C, Fairburn CG, Ostinelli EG, De Crescenzo F, Johnson C, Schmidt U, Treasure J, Favaro A, Zipfel S, Cipriani A. Comparative efficacy and acceptability of psychological interventions for the treatment of adult outpatients with anorexia nervosa: a systematic review and network meta-analysis. Lancet Psychiatry. 2021;8:215–24. https://doi.org/10.1016/s2215-0366(20)30566-6.

Kostro K, Lerman JB, Attia E. The current status of suicide and self-injury in eating disorders: a narrative review. J Eat Disord. 2014;2:19. https://doi.org/10.1186/s40337-014-0019-x.

Treasure J, Murphy T, Szmukler G, Todd G, Gavan K, Joyce J. The experience of caregiving for severe mental illness: a comparison between anorexia nervosa and psychosis. Soc Psychiatry Psychiatr Epidemiol. 2001;36:343–7. https://doi.org/10.1007/s001270170039.

Gonzalez N, Padierna A, Martin J, Aguirre U, Quintana JM. Predictors of change in perceived burden among caregivers of patients with eating disorders. J Affect Disord. 2012;139:273–82. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jad.2012.02.013S0165-0327(12)00109-7[pii].

Wollast R, Fossion P, Kotsou I, Rebrassé A, Leys C. interoceptive awareness and anorexia nervosa: when emotions influence the perception of physiological sensations. J Nerv Ment Dis. 2022;210:390–3. https://doi.org/10.1097/nmd.0000000000001458.

Leppanen J, Brown D, McLinden H, Williams S, Tchanturia K. The Role of Emotion Regulation in Eating Disorders: A Network Meta-Analysis Approach. Front Psychiatry. 2022;13:793094. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyt.2022.793094.

Troop NA, Allan S, Treasure JL, Katzman M. Social comparison and submissive behaviour in eating disorder patients. Psychol Psychother. 2003;76:237–49. https://doi.org/10.1348/147608303322362479.

Hartmann A, Zeeck A, Barrett MS. Interpersonal problems in eating disorders. Int J Eat Disord. 2010;43:619–27. https://doi.org/10.1002/eat.20747.

Williams GJ, Power KG, Millar HR, Freeman CP, Yellowlees A, Dowds T, Walker M, Campsie L, MacPherson F, Jackson MA. Comparison of eating disorders and other dietary/weight groups on measures of perceived control, assertiveness, self-esteem, and self-directed hostility. Int J Eat Disord. 1993;14:27–32. https://doi.org/10.1002/1098-108x(199307)14:1%3c27::aid-eat2260140104%3e3.0.co;2-f.

Yamada A, Katsuki F, Kondo M, Sawada H, Watanabe N, Akechi T. Association between the social support for mothers of patients with eating disorders, maternal mental health, and patient symptomatic severity: a cross-sectional study. J Eat Disord. 2021;9:8. https://doi.org/10.1186/s40337-020-00361-w.

Coomber K, King RM. Coping strategies and social support as predictors and mediators of eating disorder carer burden and psychological distress. Soc Psychiatry Psychiatr Epidemiol. 2012;47:789–96. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00127-011-0384-6.

Sepúlveda AR, Graell M, Berbel E, Anastasiadou D, Botella J, Carrobles JA, Morandé G. Factors associated with emotional well-being in primary and secondary caregivers of patients with eating disorders. Eur Eat Disord Rev. 2012;20:e78-84. https://doi.org/10.1002/erv.1118.

Martin J, Padierna A, Aguirre U, Gonzalez N, Munoz P, Quintana JM. Predictors of quality of life and caregiver burden among maternal and paternal caregivers of patients with eating disorders. Psychiatry Res. 2013;210:1107–15. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.psychres.2013.07.039.

Iapichino E, Rucci P, Corbani IE, Apter G, Quartieri Bollani M, Cauli G, Gala C, Bassi M. Development and validation of an abridged version of the Social Provisions Scale (SPS-10) in Italian. Journal of Psychopathology. 2016;22:157–63.

Katsuki F, Yamada A, Kondo M, Sawada H, Watanabe N, Akechi T, Rucci P. Development and validation of the 10-item Social Provisions Scale (SPS-10) Japanese version. Nagoya Med J. 2020;56:229–39.

Sakano Y, Tohjoh M. The General Self/Efficay Scale (GSES): Scale development and validation. J Assoc Behav Cognitive Ther. 1986;12:73–82.

Moroi K. Dimensions of the revised UCLA Loneliness Scale. Ann Rep Dep Soc Hum Stud Lang Lit. 1992;42:23–51.

Russell DW. UCLA Loneliness Scale (Version 3): reliability, validity, and factor structure. J Pers Assess. 1996;66:20–40. https://doi.org/10.1207/s15327752jpa6601_2.

Mishima N, Kubota S, Nagata S. The development of a questionnaire to assess the attitude of active listening. J Occup Health. 2000;42:111–8.

Kojima M, Furukawa TA, Takahashi H, Kawai M, Nagaya T, Tokudome S. Cross-cultural validation of the Beck Depression Inventory-II in Japan. Psychiatry Res. 2002;110:291–9. https://doi.org/10.1016/s0165-1781(02)00106-3.

Beck AT, Steer RA, Brown GK. Manual for the Beck Depression Inventory Second edition(BDI-II). San Antonia, TX: The Psychological corporation; 1996.

Furukawa TA, Kawakami N, Saitoh M, Ono Y, Nakane Y, Nakamura Y, Tachimori H, Iwata N, Uda H, Nakane H, Watanabe M, Naganuma Y, Hata Y, Kobayashi M, Miyake Y, Takeshima T, Kikkawa T. The performance of the Japanese version of the K6 and K10 in the World Mental Health Survey Japan. Int J Methods Psychiatr Res. 2008;17:152–8. https://doi.org/10.1002/mpr.257.

Kessler RC, Barker PR, Colpe LJ, Epstein JF, Gfroerer JC, Hiripi E, Howes MJ, Normand SL, Manderscheid RW, Walters EE, Zaslavsky AM. Screening for serious mental illness in the general population. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2003;60:184–9. https://doi.org/10.1001/archpsyc.60.2.184.

Martínez-González MA, Gual P, Lahortiga F, Alonso Y, de Irala-Estévez J, Cervera S. Parental factors, mass media influences, and the onset of eating disorders in a prospective population-based cohort. Pediatrics. 2003;111:315–20. https://doi.org/10.1542/peds.111.2.315.

Quiles Marcos Y, Terol Cantero MC. Assesment of social support dimensions in patients with eating disorders. Span J Psychol. 2009;12:226–35. https://doi.org/10.1017/s1138741600001633.

Acknowledgements

The authors wish to thank Takao Suzuki of the family support group for eating disorders (“Pokoapoko”) for his support. We also thank all participants.

Funding

This study was supported by a Grant-in-Aid for Scientific Research (KAKENHI Grant Number 16K12256) from the Japanese Ministry of Education, Science, and Technology.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

FK, AY, HS, and NW designed this study. FK wrote the manuscript. FK and AY conducted the recruitment and data collection. NW, MK, and AT supervised the study and edited the various drafts of the manuscript. All the authors have read and approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

This study was approved by the Ethics Review Committee of Nagoya City University Graduate School of Medical Sciences, Japan (Ref: No 60–17-0001). All participants provided written informed consent to participate in this study.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

FK has received speaker fees from Otsuka Pharmaceutical Co., Ltd. AY has received medical fees from Gifu Hospital, speaker fees from Aichi Education and Sports Foundation, Kyowa Pharmaceutical Industry Co., Ltd., Meiji Seika Pharma Co., Ltd, Mental Care Association Japan, Mochida Pharmaceutical Co., Ltd., Otsuka Pharmaceutical Co., Ltd., Shionogi & Co., Ltd., and other fees from Nagoya City. HS declares no conflicts of interest. MK reports a grant from Novartis Pharma K.K., personal fees from Shionogi & Co., Ltd., and personal fees from Yoshitomiyakuhin Corporation, outside the submitted work. TA has received lecture fees from Astra Zeneca Co., Ltd., Daiichi Sankyo Co., Ltd., Dainippon-Sumitomo Co., Ltd., Eisai Co., Ltd., Janssen Co., Ltd., Kyowa Co., Ltd., Eli Lilly Japan K.K., MSD K.K., Meiji -Seika Pharma Co., Ltd., Mochida Co., Ltd., Nipro Co., Ltd., Nihon-Zoki Co., Ltd., Otsuka Pharmaceutical Co., Ltd., Pfizer Co., Ltd., Takeda Co., Ltd., and Tsumura Co., Ltd. TA has received research funds from Daiichi Sankyo Co., Ltd., FUJIFILM RI Pharma Co., Ltd., MSD Co., Ltd., Otsuka Co., Ltd., and Shionogi Co., Ltd. NW has received royalties from Sogensha, Medical View, and Advantage Risk Management. TA has received royalties from the Igaku-shoin. TA is the inventor of the pending patents (2019–017498 & 2020–135195).

Additional information

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/. The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver (http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/) applies to the data made available in this article, unless otherwise stated in a credit line to the data.

About this article

Cite this article

Katsuki, F., Yamada, A., Kondo, M. et al. Association between social support for mothers of patients with eating disorders and mothers’ active listening attitude: a cohort study. BioPsychoSocial Med 17, 4 (2023). https://doi.org/10.1186/s13030-023-00262-9

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s13030-023-00262-9