Abstract

Board games are played by moving game pieces in particular ways on special boards marked with patterns. To clarify the possible roles of board game use in psychosomatic medicine, the present review evaluated studies that investigated the effects of this activity on health education and treatment. A literature search conducted between January 2012 and August 2018 identified 83 relevant articles; 56 (67%) targeted education or training for health-related problems, six (7%) examined basic brain mechanisms, five (6%) evaluated preventative measures for dementia or contributions to healthy aging, and three (4%) assessed social communication or public health policies. The results of several randomized controlled trials indicated that the playing of traditional board games (e.g., chess, Go, and Shogi) helps to improve cognitive impairment and depression, and that the playing of newly developed board games is beneficial for behavioral modifications, such as the promotion of healthy eating, smoking cessation, and safe sex. Although the number of studies that have evaluated board game use in terms of mental health remains limited, many studies have provided interesting findings regarding brain function, cognitive effects, and the modification of health-related lifestyle factors.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Board games are played by moving game pieces in particular ways on special boards marked with patterns [1]. For example, one game originated in northern India in the sixth century AD and spread to Eastern as well as Western countries. In the West, it spread to Persia and then to Spain via the Moorish conquest, and then throughout Europe, where it ultimately became “chess.” In the East, this game became “Xiangqi” in China, “Shogi” in Japan, and a variety of similar games in other countries. Other popular board games that use two patterns for the game pieces include “Go” and “Othello,” also known as “Reversi.”

In the field of psychosomatic medicine, board game playing is sometimes regarded as a leisure activity, and engagement in this type of activity has been shown to protect against dementia and cognitive decline in elderly individuals [2]. For example, a 20-year prospective population-based study conducted in southwestern France investigated the relationship between the playing of board games and the risk of subsequent dementia [3]. Of the 3675 participants without dementia in that study, 1176 (32%) reported regular board game playing and 840 (23%) developed dementia during the follow-up period. The risk of dementia was 15% lower in board game players than in non-players, and board game players exhibited lesser declines in Mini-Mental State Examination (MMSE) scores and less incident depression than did non-players. Although the mechanisms underlying the reduced risk of dementia in board game players have yet to be elucidated fully, these games require players to be proactive and to anticipate, thinking several steps ahead, during play. These processes may enhance logical thinking and prevent declines in cognitive function. Individuals may also engage in non-verbal communication while playing board games, and players are more likely to have the opportunity to gather and participate in a fun activity with others. These factors could enhance individuals’ social networks, which also protects against cognitive decline. Furthermore, in terms of leisure activities, board game playing may also be a form of stress management [4], as the fight-or-flight response is regulated safely within the sophisticated structures of match-type games. Board game playing could also be a form of art therapy, similar to miniature garden therapy [5], facilitating infinite internal manifestations within a narrow space.

In terms of education, the playing of board games may help children learn to follow rules and stay seated for a certain amount of time, and it may increase children’s concentration levels [6]. For students and trainees, board game use can enhance health education by stimulating players’ interests and motivation. A search of the Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews [7] identified a total of 2079 unique citations related to educational games, such as board games and games based on television shows. Of these citations, 84 were potentially eligible for review based on methodological quality, number of participants, interventions, and outcomes of interest, and two randomized controlled trials (RCTs) were chosen. The first study [8] was based on the television game show “Family Feud” and focused on infection control; the group that was randomized to play the game had significantly higher scores on a knowledge test. The second study [9] compared game-based learning (using “Snakes and Ladders”) with traditional case-based learning of stroke prevention and management information. Although the two study groups did not have significantly different knowledge test scores immediately or 3 months after the intervention, the reported level of enjoyment was higher in the game-based learning group. The findings of an original review of articles published through January 2012 [7] neither confirmed nor refuted the utility of game playing as a teaching strategy for health professionals. Thus, the present study aimed to clarify the possible roles of board game use in psychosomatic medicine through a literature search for articles published after 2012 that focused on the effects of board game playing on health-related issues.

Mind/body changes due to board game use

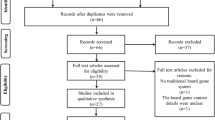

Using “board game” as a PubMed search term, 83 studies published between January 2012 and August 2018 were identified; 56 (67%) articles targeted education or training for health-related problems, six (7%) examined basic brain mechanisms, five (6%) evaluated preventative measures for dementia or contributions to healthy aging, and three (4%) assessed social communication or public health policies. The major studies that investigated the effects of traditional board game use are shown in Table 1 [10,11,12,13,14,15,16,17,18,19,20,21,22,23,24,25,26,27,28,29,30,31,32,33]; some of the articles listed in the table were identified in the reference sections of the original 56 articles or other databases.

Experimental studies investigating brain magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) or electroencephalographic (EEG) signals in professional board game players [10, 22, 26,27,28, 31] demonstrated that the basal ganglia play an important role in the ability to rapidly determine, or intuit, the best subsequent move in a game situation [24]. Additionally, variations in heart rate and eye movements were examined as physiological parameters during chess play [10, 14, 16]. In case studies and case-control studies, board games were shown to effectively improve symptoms in individuals who experience panic attacks [11], as well as those with attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder (ADHD) [21] and Alzheimer’s disease (AD) [29]. On the other hand, one study revealed possible hazardous effects associated with the playing of “Go” in individuals with seizure disorders [23]. The amounts of real and virtual playing of board games have increased recently and, as a result, the number of published studies assessing the effects of board game use has also increased [12, 13, 17, 19]. The increase in game play is likely due to the prevalence of computer systems in the current age of information and communication technology (ICT) and artificial intelligence (AI).

Recent RCTs evaluating board game use

According to a recent meta-analysis of four studies that investigated chess play [14], age and skill have differential effects on two tasks during game play: selecting the best move for chess positions and recalling chess game positions. The authors found that age was associated negatively, whereas skill was associated positively, with performance in both tasks. Another RCT showed that an intervention using Go improved depression and increased serum levels of brain-derived neurotrophic factor (BDNF) in patients with AD [20]. Similarly, players’ depression and anxiety levels were shown to decrease significantly during a 6-week stress management intervention that utilized Shogi games [25]. Although these data have been presented only at a scientific conference, they will soon be published in this special series. The authors also reported that several patterns of negative cognitive distortion (e.g., lower levels of activity) significantly improved following completion of the Shogi program compared with those in a wait-list control group. An RCT showed that the playing of “Ska,” a traditional board game in Thailand [32], enhanced cognitive function in terms of memory and attention in elderly subjects.

Of the 83 articles identified in the present PubMed literature search, 12 articles [34,35,36,37,38,39,40,41,42,43,44,45] report on RCTs that assessed non-traditional board games (Table 2). A variety of board games has been developed to aid in the health education of patients, children, and medical trainees; most of these games are focused on behavioral modifications, such as the promotion of healthy eating [34, 38], smoking cessation [43], and safe sex [45]. For example, in a Swiss study [43], 240 current smokers were assigned randomly to a group participating in smoking cessation program employing an educational board game (“Pick-Klop”) and a wait-list control group. Compared with those in the wait-list group, individuals in the board game group were less likely to remain smokers at the end of the program and at the 3-month follow-up assessment. The authors suggested that use of the board game would be an interesting alternative for the education of smokers in the precontemplation stage.

Clinical applications of board games

Based on the results of studies investigating traditional and non-traditional board games, it was hypothesized that board game use would prevent cognitive impairment in elderly individuals and illness-prone behaviors in children and adults. Board game playing also seems to be an effective, fun means of delivering medical and safety education to students and trainees. Currently, many people spend large portions of their time playing games online and offline on television monitors, personal computers, tablets, and/or smart-phones. For example, more than half of Japanese elementary and junior-high school students play video games for more than 1 h on weekdays [46]. Thus, video game–based training will become more popular in the future.

On the other hand, a series of meta-analyses [47] found only small or null effect sizes in three models examining correlations between video game skills and cognitive ability, differences in cognitive ability between game players and non-players, and the effects of video game–based training on cognitive ability, respectively. Thus, examination of the clinical effects of real or virtual training using board games may provide more appropriate information for discussion of the advantages and disadvantages of each style of board game for future applications in clinical settings. A recent assessment of cognitive science research on board game playing [48] highlighted six suggestions for future studies: 1) do not forget about chess (i.e., a traditional board game for which large amounts of data have been collected), 2) look beyond action games and chess, 3) use optimal play to understand human play and players, 4) investigate social phenomena, 5) raise the standards for studies investigating game play as treatment, and 6) talk to real experts.

Conclusions

Although the number of studies investigating board game use remains limited, interesting findings have recently been obtained in terms of brain function, cognitive effects, and health-related lifestyle modification. Board games may also be applicable as educational tools for health professionals. Although a systematic review [7] neither confirmed nor refuted the utility of game playing as a teaching strategy for health professionals, these findings were published in 2013 and additional high-quality studies have been reported since then. Thus, it is time to re-evaluate the usefulness of games and gamifications following technological advances made in modern society. Clinical medicine is closely linked to a public health approach, and medical practices should be undertaken within the limited human, time, and financial resources available [49]. In this sense, appropriate health education programs with a board game component would be useful for both preventive and therapeutic intervention for cognitive-behavioral functioning (e.g., ADHD and dementia), psychological conditions (e.g., depression and anxiety disorders), and life-style diseases (e.g., metabolic syndromes and smoking-related diseases).

Abbreviations

- (f)MRI:

-

(functional) Magnetic resonance imaging

- AD:

-

Anno Domini

- ADHD:

-

Attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder

- AI:

-

Artificial intelligence

- BDNF:

-

Brain-derived neurotrophic factor

- EEG:

-

Electroencephalographic

- HIV:

-

Human immunodeficiency virus

- ICT:

-

Information and communication technology

- RCT:

-

Randomized controlled trial

References

Kyppo J. Board games: throughout the history and multidimensional spaces. NJ, U.S: World Scientific Publishing Co Inc; 2018.

Akbaraly TN, Portet F, Fustinoni S, Dartigues JF, Artero S, Rouaud O, Touchon J, Ritchie K, Berr C. Leisure activities and the risk of dementia in the elderly: results from the three-city study. Neurology. 2009;73:854–61.

Dartigues JF, Foubert-Samier A, Le Goff M, Viltard M, Amieva H, Orgogozo JM, Barberger-Gateau P, Helmer C. Playing board games, cognitive decline and dementia: a French population-based cohort study. BMJ Open. 2013 Aug 29;3(8):e002998.

Hoffmann A, Christmann CA, Bleser G. Gamification in stress management apps: a critical app review. JMIR Serious Games. 2017 Jun 7;5(2):e13.

Ueda T. The availability of shogi for art therapy. Jpn Bull Arts Ther. 2002;33:38–45 [in Japanese].

Riggs AE, Young AG. Developmental changes in children's normative reasoning across learning contexts and collaborative roles. Dev Psychol. 2016;52:1236–46.

Akl EA, Kairouz VF, Sackett KM, Erdley WS, Mustafa RA, Fiander M, Gabriel C, Schünemann H. Educational games for health professionals. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2013 Mar 28;3:CD006411.

Burke CT. The influences of teaching strategies and reinforcement techniques on health care workers’ learning and retention [PhD thesis]. Hattiesburg: University of Southern Mississippi; 2001. [UM I Microform 3038675]

Telner D, Bujas-Bobanovic M, Chan D, Chester B, Marlow B, Meuser J, Rothman A, Harvey B. Game-based versus traditional case-based learning: comparing effectiveness in stroke continuing medical education. Can Fam Physician. 2010;56(9):e345–51.

Fuentes JP, Villafaina S, Collado-Mateo D, de la Vega R, Gusi N, Clemente-Suárez VJ. Use of biotechnological devices in the quantification of psychophysiological workload of professional chess players. J Med Syst. 2018;42(3):40.

Barzegar K, Barzegar S. Chess therapy: a new approach to curing panic attack. Asian J Psychiatr. 2017;30:118–9.

Schaigorodsky AL, Perotti JI, Billoni OV. A study of memory effects in a chess database. PLoS One. 2016;11(12):e0168213.

Chassy P, Gobet F. Risk taking in adversarial situations: civilization differences in chess experts. Cognition. 2015 Aug;141:36–40.

Sheridan H, Reingold EM. Expert vs novice differences in the detection of relevant information during a chess game: Evidence from eye movements. Front Psychol. 2014;5:941.

Moxley JH, Charness N. Meta-analysis of age and skill effects on recalling chess positions and selecting the best move. Psychon Bull Rev. 2013;20(5):1017–22.

Leone MJ, Petroni A, Fernandez Slezak D, Sigman M. The tell-tale heart: heart rate fluctuations index objective and subjective events during a game of chess. Front Hum Neurosci. 2012;6:273.

Barradas-Bautista D, Alvarado-Mentado M, Agostino M, Cocho G. Cancer growth and metastasis as a metaphor of go gaming: an Ising model approach. PLoS One. 2018;13(5):e0195654.

Bae J, Cha YJ, Lee H, Lee B, Baek S, Choi S, Jang D. Social networks and inference about unknown events: a case of the match between Google's AlphaGo and Sedol Lee. PLoS One. 2017;12(2):e0171472.

Silver D, Huang A, Maddison CJ, Guez A, Sifre L, van den Driessche G, Schrittwieser J, Antonoglou I, Panneershelvam V, Lanctot M, Dieleman S, Grewe D, Nham J, Kalchbrenner N, Sutskever I, Lillicrap T, Leach M, Kavukcuoglu K, Graepel T, Hassabis D. Mastering the game of go with deep neural networks and tree search. Nature. 2016;529(7587):484–9.

Lin Q, Cao Y, Gao J. The impacts of a GO-game (Chinese chess) intervention on Alzheimer disease in a northeast Chinese population. Front Aging Neurosci. 2015;7:163.

Kim SH, Han DH, Lee YS, Kim BN, Cheong JH, Han SH. Baduk (the game of go) improved cognitive function and brain activity in children with attention deficit hyperactivity disorder. Psychiatry Investig. 2014;11(2):143–51.

Jung WH, Kim SN, Lee TY, Jang JH, Choi CH, Kang DH, Kwon JS. Exploring the brains of Baduk (go) experts: gray matter morphometry, resting-state functional connectivity, and graph theoretical analysis. Front Hum Neurosci. 2013;7:633.

Lee MK, Yoo J, Cho YJ, Lee BI, Heo K. Reflex epilepsy induced by playing go-stop or Baduk games. Seizure. 2012;21(10):770–4.

Tanaka K. Brain mechanisms of intuition in shogi experts. Brain Nerve. 2018;70:607–15 [in Japanese].

Nakao M, Furukawa H, Oomine A, Fukumoto T, Ono H, Obara A, Noda S, Kitashima C. Introduction of “Shogi” health promotion project in Kakogawa City. Tokyo: Abstract of the 24th Annual Scientific Conference of the Japanese Society of Behavioral Medicine; 2017. [in Japanese]

Wan X, Cheng K, Tanaka K. The neural system of post-decision evaluation in rostral frontal cortex during problem-solving tasks. eNeuro. 2016;29:3(4).

Wan X, Cheng K, Tanaka K. Neural encoding of opposing strategy values in anterior and posterior cingulate cortex. Nat Neurosci. 2015 May;18(5):752–9.

Nakatani H, Yamaguchi Y. Quick concurrent responses to global and local cognitive information underlie intuitive understanding in board-game experts. Sci Rep. 2014;4:5894.

Aoyagi M, Ogawa T. Effects of denture wearing and chewing in elderly with dementia repeating aspiration pneumonia. J Jpn Psychiatr Nurs Soc. 2013;56:118–9 [Japanese].

Wan X, Takano D, Asamizuya T, Suzuki C, Ueno K, Cheng K, Ito T, Tanaka K. Developing intuition: neural correlates of cognitive-skill learning in caudate nucleus. J Neurosci. 2012;32:17492–501.

Duan X, Long Z, Chen H, Liang D, Qiu L, Huang X, Liu TC, Gong Q. Functional organization of intrinsic connectivity networks in Chinese-chess experts. Brain Res. 2014;1558:33–43.

Panphunpho S, Thavichachart N, Kritpet T. Positive effects of Ska game practice on cognitive function among older adults. J Med Assoc Thail. 2013;96:358–64.

van den Dries S, Wiering MA. Neural-fitted TD-leaf learning for playing Othello with structured neural networks. IEEE Trans Neural Netw Learn Syst. 2012;23:1701–13.

Nederkoorn C, Theiβen J, Tummers M, Roefs A. Taste the feeling or feel the tasting: tactile exposure to food texture promotes food acceptance. Appetite. 2018;120:297–301.

Fancourt D, Burton TM, Williamon A. The razor's edge: Australian rock music impairs men's performance when pretending to be a surgeon. Med J Aust. 2016;205:515–8.

Karbownik MS, Wiktorowska-Owczarek A, Kowalczyk E, Kwarta P, Mokros Ł, Pietras T. Board game versus lecture-based seminar in the teaching of pharmacology of antimicrobial drugs--a randomized controlled trial. FEMS Microbiol Lett. 2016;363(7):fnw045.

Sharps M, Robinson E. Encouraging children to eat more fruit and vegetables: Health vs descriptive social norm-based messages. Appetite. 2016;100:18–25.

Viggiano A, Viggiano E, Di Costanzo A, Viggiano A, Andreozzi E, Romano V, Rianna I, Vicidomini C, Gargano G, Incarnato L, Fevola C, Volta P, Tolomeo C, Scianni G, Santangelo C, Battista R, Monda M, Viggiano A, De Luca B, Amaro S. Kaledo, a board game for nutrition education of children and adolescents at school: cluster randomized controlled trial of healthy lifestyle promotion. Eur J Pediatr. 2015;174:217–28.

Fernandes SC, Arriaga P, Esteves F. Providing preoperative information for children undergoing surgery: a randomized study testing different types of educational material to reduce children's preoperative worries. Health Educ Res. 2014;29:1058–76.

Laski EV, Siegler RS. Learning from number board games: you learn what you encode. Dev Psychol. 2014;50:853–64.

Charlier N, De Fraine B. Game-based learning as a vehicle to teach first aid content: a randomized experiment. J Sch Health. 2013;83:493–9.

Swiderska N, Thomason E, Hart A, Shaw BN. Randomised controlled trial of the use of an educational board game in neonatology. Med Teach. 2013;35:413–5.

Khazaal Y, Chatton A, Prezzemolo R, Zebouni F, Edel Y, Jacquet J, Ruggeri O, Burnens E, Monney G, Protti AS, Etter JF, Khan R, Cornuz J, Zullino D. Impact of a board-game approach on current smokers: a randomized controlled trial. Subst Abuse Treat Prev Policy. 2013 Jan 17;8:3.

Cho KH, Lee KJ, Song CH. Virtual-reality balance training with a video-game system improves dynamic balance in chronic stroke patients. Tohoku J Exp Med. 2012;228:69–74.

Wanyama JN, Castelnuovo B, Robertson G, Newell K, Sempa JB, Kambugu A, Manabe YC, Colebunders R. A randomized controlled trial to evaluate the effectiveness of a board game on patients’ knowledge uptake of HIV and sexually transmitted diseases at the infectious diseases institute, Kampala, Uganda. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr. 2012;59:253–8.

National Institute for Educational Research Policy, Japanese Ministry of Education, Culture, Sports, Science and Technology. Report of investigation of scholastic ability and learning situation in Japan, 2018. http://www.nier.go.jp/18chousakekkahoukoku/index.html. [Accessed 14 Feb 2018].

Sala G, Tatlidil KS, Gobet F. Video game training does not enhance cognitive ability: a comprehensive meta-analytic investigation. Psychol Bull. 2018;144:111–39.

Chabris CF. Six suggestions for research on games in cognitive science. Topics Cog Sci. 2017;9:497–509.

Nakao M. Bio-psycho-social medicine is a comprehensive form of medicine bridging clinical medicine and public health. BioPsychoSoc Med. 2010;4:19.

Acknowledgements

The author (M.N.) appreciates the support of the members of the Japan Shogi Association and officials in Kakogawa City for conceptualizing health promotion models using board games, such as Shogi and other traditional games.

Funding

Not applicable.

Availability of data and materials

Not applicable.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

The author (MN) wrote the entire manuscript and holds final responsibility for the decision to submit the manuscript for publication. The author read and approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

Not applicable.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The author (M.N.) declares no competing interests.

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made. The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver (http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/) applies to the data made available in this article, unless otherwise stated.

About this article

Cite this article

Nakao, M. Special series on “effects of board games on health education and promotion” board games as a promising tool for health promotion: a review of recent literature. BioPsychoSocial Med 13, 5 (2019). https://doi.org/10.1186/s13030-019-0146-3

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s13030-019-0146-3