Abstract

Introduction

Persistence of human papillomavirus (HPV) infections is associated with squamous cell carcinomas of different human anatomic sites. Several studies have suggested a potential role for HPV infection, particularly HPV16 genotype, in rectal cancer carcinogenesis.. The aim of this study was to assess the frequency of oncogenic HPV 16 viral DNA sequences in rectal carcinomas cases retrieved from the pathology archive of Braga Hospital, North Portuga.

Methods

TaqMan-based type-specific real-time PCR for HPV 16 was performed using primers and probe targeting HPV16 E7 region.

Results

Most of the rectal cancer patients (88.5%, n = 206 patients), were symptomatic at diagnosis. The majority of the lesions (55.3%, n = 129) presented malignancies of polypoid/vegetant phenotype. 26.8% (n = 63) had synchronic metastasis at diagnosis. 26.2% (n = 61) patients had clinical indication for neoadjuvant therapy. Most patients with rectal cancer were stage IV (19.7% patients), followed by stage IIA (19.3%) and stage I (18.5%). All cases of the present series tested negative for HPV16.

Conclusion

The total of negative tests for HPV 16 infection is a robust argument to support the assumption that HPV 16 infection, despite of previous evidences, is not involved in rectal cancer carcinogenesis and progression.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Human papillomavirus (HPV) is one of the most common sexually transmitted infections and its relationship with some cancer types has been well established [1,2,3]. Persistent infections can progress to premalignant and malignant lesions [4] and approximately 4.8% (610,000 cases) of all cancers worldwide are attributed to HPV infection [5].

A strong causal relationship has been demonstrated between HPV and some types of cancers such as cervix uteri, penis, vulva, vagina, anus and oropharynx [4, 6]. Controversial results have been obtained regarding the role of HPVs in esophagus [6,7,8], oral cavity [6, 9], breast [10,11,12] and lung cancers [13, 14]. In cervical lesions the HPV DNA is frequently found integrated into the host genome particularly in high grade cervical intraepithelial neoplasia and invasive cancer cases [15, 16]. This type of cancer is recognized to develop through a multistep process, from premalignant lesions, cervical intraepithelial neoplasia (CIN, graded 1–3 according to severity) into cancer [17]. In oropharyngeal squamous cell carcinoma (OPSCC) besides being a well-known risk factor, HPV also is related with improved survival [18,19,20,21,22]. Moreover, HPV is detected in 80–90% of anal cancer cases, mostly HPV 16; The high frequency of HPV16 infection in this anatomic region possibly reflects a differential tropism of HPV 16 or an increased probability of HPV 16 to lead to malignant transformation in the anal mucosa [23, 24]. Not surprisingly, in recent years, a growing number of studies suggest a potential role of persistent HPV infection also in colon and rectal carcinogenesis [25], but the association between HPV and rectal cancer (RC) remains controversial and inconclusive since HPV detection rate ranges from 0 to 84% [25,26,27]. Despite of several studies have focused on the association of HPV and RC, few reports dedicate a large study on rectal cancer, particularly. Based on this lack of precise information about this topic, we sought to investigate the frequency of HPV 16, and its potential association with rectal carcinoma. The current study was designed to specifically assess the incidence of HPV16 viral DNA sequences in rectal cancer carcinomas derived from a series of RC patients treated at Braga Hospital, North Portugal.

Methods

Rectal tumor series

Data from 233 patients with confirmed rectal cancer treated in Hospital de Braga, Portugal, from 2005 to 2010 were collected prospectively. Tumor localization was recorded and classified as rectum, when tumors localized between anal verge and 15 cm at rigid rectoscopy [28].

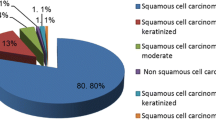

The histological type of rectal cancer was classified by an experienced pathologist (FP) and tumor staging was graded according to the TNM classification, sixth edition [29].

From the initial group of 233 rectal cancer cases, patients with tumor localized at the proximal rectum (n = 49) and patients submitted to neoadjuvant therapy (n = 40) were excluded from the study. Thus, tissue samples from 144 patients were performed for DNA extraction and HPV analyses.

Processing of tumor samples and DNA extraction

The DNA was extracted from formalin fixed paraffin embedded (FFPE) samples using the DNA QIAamp Micro Kit (Qiagen, USA) according to manufacturer’s instructions. Briefly, 4–6 formalin-fixed, paraffin-embedded 10-μm sections were submitted to deparaffinization of sections with 100% xylene, followed by washes of ethanol (100, 90, and 50%) and incubation with DNA extraction buffer overnight. All DNA samples were quantified using NanoDrop 2000 (ThermoScientific) and maintained at − 20 °C until use.

HPV analysis

TaqMan-based type-specific real-time PCR for HPV 16 was performed using primers (forward 5′-GATGAAATAGATGGTCCAGC-3′ and reverse 5′- GCTTTGTACGCACAACCGAAGC-3′) and TaqMan probe (5′- 6FAMCAAGCAGAACCGGACAG-MGBNFQ-3′) E7 region of HPV type 16. The reaction mixture was prepared as follows: TaqMan Universal PCR Master Mix 1 x (Applied Biosystem, Inc., EUA), 400 nM of each primer, 200 nM TaqMan probe and water DNAse and RNAse free. PCR amplifications were carried out after the addition of 5 μl of the sample containing template DNA in a final volume of 25 μL of the PCR reaction mixture. The amplification conditions were as follows: initial denaturation for 10 min at 95 °C, followed by 40 amplification cycles of 15 s each at 95 °C and 1 min at 60 °C (annealing-extension step). Each PCR reaction included negative (water) and positive controls (DNA extracted from cell CasKi). All samples and controls were tested in duplicate and were considered positive when both replicated amplified in a cycle < 38 [30].

As a positive control for the quality of the template DNA, primers for β-globin gene were included in the reactions, as described previously [7].

Results

Rectal cancer patient’s characterization

The characteristics of the in Table 1 and previously published [31]. Of the 233 rectal cancers patients, most (50.6%, n = 118), were localized in the middle third, followed by distal rectum, 28.3% (n = 66), and proximal rectum in 21% (n = 49).

Most of the rectal cancer patients (88.5%, n = 206 patients), and the instrumental diagnosis performed by by total colonoscopy in 79.8% (n = 186) and rectosigmoidoscopy in 18.9% (n = 44). In 1.3% (n = 3) it was impossible to perform an endoscopic exam (rectal stenosis).

The majority of the lesions (55.3%, n = 129) presented malignancies of polypoid/vegetant phenotype. The remaining 21.0% (n = 49) were ulcerated lesions, and 10.7% (n = 25 showed an infiltrative pattern; 9.0% (n = 21) were exofitic cancers; 0.4% (n = 1) were villous aspect and for the reminder seven patients (3%) we did not have macroscopic appearance information.

Sixtythree out of 233 (26.8%) had ....had synchronous metastasis at diagnosis, more frequently lymph node (10.2) and hepatic metastasis (8.5%). Pelvic magnetic resonance (MR) and rectal endoscopic ultrasound (EUS) were used combined for local staging. After staging, 26.2% (n = 61) patients had indication for neoadjuvant therapy.

Finally, postoperative histological staging, graded according to the TNM classification, seventh edition (American Joint Committee on Cancer - AJCC). Most patients with rectal cancer were stage IV (19.7% patients), followed by stage IIA (19.3%) and stage I (18.5%).

HPV detection

Patients with carcinoma localized at the proximal rectum (n = 49) and patients submitted to neoadjuvant therapy (n = 40) were excluded from the initial group of 233 rectal cancer cases. Thus, tissue samples from 144 patients were subjected to DNA extraction and HPV analysis. None of the 144 samples analyzed for HPV16 E7 DNA tested positive. All cases were unequivocally negative.

Discussion

The growing evidences that HPV is associated with carcinogenic processes of squamous cell carcinomas arising at different anatomical sites stimulated several researches to investigate the presence of HPV infections in different tumours types. Indeed, viral infection are responsible for about 15% of cancers, mainly by favoring genetic instability and inducing chromosomal aberrations [31,32,33]. The role of HPV in cancer development has already well documented for cervix uteri, penis, vulva, vagina, oropharynx, and anal canal cancers worldwide. However, there are scarce data concerning the relationship between HPV and rectal cancer in Portugal [4, 6, 23, 24].

Despite colonrectal is the third most common type of cancer [34,35,36,37] and the fourth most frequent cause of cancer death [34,35,36,37,38], in Portugal, this neoplasia is the second most frequent cancer and the second leading cause of cancer death in both genders [39]. About rectal cancer, in particular, the district of Braga exhibited incidence of 16.8/100,000 inhabitants in 2008 [40], which is substantial prevalence taking in account that Braga population is currently 136,885 (official information from Braga Council of the urban perimeter, 2011) people.

Most of CRCs are demonstrated to developed from a benign pre-neoplastic lesion (polyp).. The transition from normal mucosa to malignancy, through the adenoma-carcinoma sequence, usually takes ten or more years and is characterized by the change in innumerable genes associated with the maintenance of cellular homeostasis [41, 42]. Internal factors such as personal or family history of CRC and/or polyps, personal history of inflammatory bowel disease and hereditary genetic conditions confer a higher risk of developing CRC [42, 43]. However, many cases can be associated to a plethora of environmental and compartmental factors such as sedentary lifestyle, obesity, long-term smoking, excessive alcohol consumption and diet [42, 44, 45]. Among external factors, HPV has emerged as an important variable be considered for many carcinomas. HPV infection association with colon and rectal cancer is particularly contentious [6] and doubtful etiological source of CRC, since HPV detection rates range from 0 to 84% [46,47,48,49,50]., Most of these studies, however, did not take into account the tumor localization, and/or included series of malign and benign forms of cancer). Also, several reports propone a positive association and suggest a possible role of HPV in colorectal cancers development [46, 48, 49, 51] but non-clarifying the nature of the association [52]. A possible relationship between HPV and RC, could represent an impact in the global incidence of this cancer, as it could be possible to implement strategies for screening and control this malignancy through HPV testing.

Variation of HPV infection frequencies in rectal cancer is extraordinarily high, as anticipated, probably due to differences in methodologies used, preservation of the samples in retrospective series and some particular characteristics of populations [23]. Despite the controversies, is far to be proved the direct relationship between HPV and rectal cancer, as occur with cervical cancer [53]. The data available are controversial and incontestably intriguing. Our study has an important limitation because we opted to use only sequences for HPV 16 test because it is the most common type in various anatomic sites worldwide [24]. The results we achieved exclude the possible role of this HPV 16 in rectal carcinogenesis, which is endorsed by others [53]. These data, however, encourage further studies, with larger series and involving other segments of colon aiming to investigate the presence of other types of HPV.

Availability of data and materials

Please contact author for data requests.

Abbreviations

- CIN:

-

Cervical Intraepithelial Neoplasia

- CRC:

-

Colorectal Cancer

- HPV:

-

Human papillomavirus

- IARC:

-

International Agency for Research on Cancer

- OPSCC:

-

Oropharyngeal Squamous Cell Carcinoma

- RC:

-

Rectal Cancer

References

Zur HH. Papillomaviruses and cancer: from basic studies to clinical application. Nat Rev Cancer. 2002;2:342–50.

Rusan M, Li YY, Hammerman PS. Genomic landscape of human papillomavirus-associated cancers. Clin Cancer Res. 2015;21(9):2009–19.

Schiffman M, Doorbar J, Wentzensen N, de Sanjosé S, Fakhry C, Monk BJ, Stanley MA, Franceschi S. Carcinogenic human papillomavirus infection. Nat Rev Dis Primers. 2016;2:16086.

Van Dyne EA, Henley SJ, Saraiya M, Thomas CC, Markowitz LE, Benard VB. Trends in human papillomavirus-associated cancers - United States, 1999-2015. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2018;67(33):918–24.

de Martel C, Ferlay J, Franceschi S, Vignat J, Bray F, Forman D, Plummer M. Global burden of cancers attributable to infections in 2008: a review and synthetic analysis. Lancet Oncol. 2012;13(6):607–15. https://doi.org/10.1016/S1470-2045(12)70137-7.

IARC Working Group on the Evaluation of Carcinogenic Risks to Humans. Human papillomaviruses. IARC Monogr Eval Carcinog Risks Hum. 2007;90:1–636.

da Costa AM, Fregnani JHTG, Pastrez PRA, Mariano VS, Neto CS, Guimarães DP, de Oliveira KMG, Neto SAZ, Nunes EM, Ferreira S, Sichero L, Villa LL, Syrjanen KJ, Longatto-Filho A. Prevalence of high risk HPV DNA in esophagus is high in Brazil but not related to esophageal squamous cell carcinoma. Histol Histopathol. 2018;33(4):357–63.

Pastrez PRA, Mariano VS, da Costa AM, Silva EM, Scapulatempo Neto C, Guimarães DP, Fava G, Neto SAZ, Nunes EM, Sichero L, Villa LL, Syrjanen KJ, Longatto-Filho A. The relation of HPV infection and expression of p53 and p16 proteins in esophageal squamous cells carcinoma. J Cancer. 2017;8(6):1062–70.

Syrjänen S. Oral manifestations of human papillomavirus infections. Eur J Oral Sci. 2018;126(Suppl 1):49–66.

Ghaffari H, Nafissi N, Hashemi-Bahremani M, Alebouyeh MR, Tavakoli A, Javanmard D, Bokharaei-Salim F, Mortazavi HS, Monavari SH. Molecular prevalence of human papillomavirus infection among Iranian women with breast cancer. Breast Dis. 2018. https://doi.org/10.3233/BD-180333.

Kouloura A, Nicolaidou E, Misitzis I, Panotopoulou E, Kassiani T, Smyrniotis V, Corso G, Veronesi P, Arkadopoulos N. HPV infection and breast cancer. Results of a microarray approach. Breast. 2018;40:165–9. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.breast.2018.05.010 Epub 2018 Jun 4. Erratum in: Breast. 2018 Oct;41:136. PubMed PMID: 29890463.

Malhone C, Longatto-Filho A, Filassi JR. Is human papilloma virus associated with breast Cancer? A review of the molecular evidence. Acta Cytol. 2018;62(3):166–77.

Kim Y, Pierce CM, Robinson LA. Impact of viral presence in tumor on gene expression in non-small cell lung cancer. BMC Cancer. 2018 Aug 22;18(1):843. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12885-018-4748-0.

Liang H, Pan Z, Cai X, Wang W, Guo C, He J, Chen Y, Liu Z, Wang B, He J. LiangW; AME lung Cancer cooperative group. The association between human papillomavirus presence and epidermal growth factor receptor mutations in Asian patients with non-small cell lung cancer. Transl Lung Cancer Res. 2018;7(3):397–403.

Dooley KE, Warburton A, McBride AA. Tandemly Integrated HPV16 Can Form a Brd4-Dependent Super-Enhancer-Like Element That Drives Transcription of Viral Oncogenes. mBio. 2016;7(5):e01446–16. https://doi.org/10.1128/mBio.01446-16.

Vande Pol SB, Klingelhutz AJ. Papillomavirus E6 oncoproteins. Virology. 2013;445(1–2):115–37.

Feng D, Yan K, Zhou Y, Liang H, Liang J, Zhao W, Dong Z, Ling B. Piwil2 is reactivated by HPV oncoproteins and initiates cell reprogramming via epigenetic regulation during cervical cancer tumorigenesis. Oncotarget. 2016;7(40):64575–88.

Gillison ML, Koch WM, Capone RB, Spafford M, Westra WH, Wu L, Zahurak ML, Daniel RW, Viglione M, Symer DE, Shah KV, Sidransky D, Gillison ML, et al. Evidence for a causal association between human papillomavirus and a subset of head and neck cancers. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2000;92:709–20.

Fakhry C, Zhang Q, Nguyen-Tan PF, Rosenthal D, El-Naggar A, Garden AS, Soulieres D, Trotti A, Avizonis V, Ridge JA, Harris J, Le QT, Gillison M. Human papillomavirus and overall survival after progression of oropharyngeal squamous cell carcinoma. J Clin Oncol. 2014;32(30):3365–73.

Guo T, Qualliotine JR, Ha PK, Califano JA, Kim Y, Saunders JR, Blanco RG, D'Souza G, Zhang Z, Chung CH, Kiess A, Gourin CG, Koch W, Richmon JD, Agrawal N, Eisele DW, Fakhry C. Surgical salvage improves overall survival for patients with HPV-positive and HPV-negative recurrent locoregional and distant metastatic oropharyngeal cancer. Cancer. 2015;121(12):1977–84.

Iyer NG, Dogan S, Palmer F, Rahmati R, Nixon IJ, Lee N, Patel SG, Shah JP, Ganly I. Detailed analysis of Clinicopathologic factors demonstrate distinct difference in outcome and prognostic factors between surgically treated HPV-positive and negative Oropharyngeal Cancer. Ann Surg Oncol. 2015;13:4411–21.

Larsen CG, Jensen DH, Carlander AF, Kiss K, Andersen L, Olsen CH, Andersen E, Garnæs E, Cilius F, Specht L, von Buchwald C. Novel nomograms for survival and progression in HPV+ and HPV- oropharyngeal cancer: a population-based study of 1,542 consecutive patients. Oncotarget. 2016;7(44):71761–72.

Alemany L, Saunier M, Alvarado-Cabrero I, et al. Human papillomavirus DNA prevalence and type distribution in anal carcinomas worldwide. Int J Cancer. 2015;136:98–107.

De Vuyst H, Clifford GM, Nascimento MC, Madeleine MM, Franceschi S. Prevalence and type distribution of human papillomavirus in carcinoma and intraepithelial neoplasia of the vulva, vagina and anus: a meta-analysis. Int J Cancer. 2009;124:1626–36.

Lorenzon L, Ferri M, Pilozzi E, Torrisi MR, Ziparo V, French D. Human papillomavirus and colorectal cancer: evidences and pitfalls of published literature. Int J Color Dis. 2011;26:135–42.

Baandrup L, Thomsen LT, Olesen TB, Andersen KK, Norrild B, Kjaer SK. The prevalence of human papillomavirus in colorectal adenomas and adenocarcinomas: a systematic review and metaanalysis. Eur J Cancer. 2014;50:1446–61.

Damin DC, Ziegelmann PK, Damin AP. Human papillomavirus infection and colorectal cancer risk: a meta-analysis. Color Dis. 2013;15:e420–8.

Tanaka A, Sadahiro S, Suzuki T, Okada K, Saito G. A comparison of the localization of rectal carcinomas according to the general rules of the Japanese classification of colorectal carcinoma (JCCRC) and Western guidelines. Surg Today. 2017;47(9):1086–93.

Greene FL, Page DL, Fleming ID, et al. E. AJCC Cancer Staging Manual. 6th ed. New York: Springer; 2002.

Walboomers JM, Jacobs MV, Manos MM, Bosch FX, Kummer JA, Shah KV, Snijders PJ, Peto J, Meijer CJ, Muñoz N. Human papillomavirus is a necessary cause of invasive cervical cancer worldwide. J Pathol. 1999;189:12–9.

Martins SF, Amorim R, Reis RM, Pinheiro C, Rodrigues M, et al. A hospital based cohort study of colorectal Cancer cases treated at Braga hospital, northern Portugal. J Gastroint Dig Syst. 2013;3:146. https://doi.org/10.4172/2161-069X.1000146.

Giuliani L, Ronci C, Bonifacio D, Di Bonito L, Favalli C, Perno CF, Syrjanen K, Ciotti M. Detection of oncogenic DNA viruses in colorectal Cancer. Anticancer Res. 2008;28:1405–10.

Picanço-Junior OM, Oliveira AL, Freire LT, Brito RB, Villa LL, Matos DMD. Differentiation., association between human papillomavirus and colorectal adenocarcinoma and its influence on tumor staging and degree of cell. Arq Bras Cir Dig. 2014;27(3):172–6.

Svagzdys S, Lesauskaite V, Pavalkis D, Nedzelskienė I, Pranys D, Tamelis A. Microvessel density as new prognostic marker after radiotherapy in rectal cancer. BMC Cancer. 2009;9(1):95.

Des Guetz G, Uzzan B, Nicolas P, Cucherat M, Morere JF. Benamouzig R BJ andPerretG-Y. microvessel density and VEGF expression are prognostic factors in colorectal cancer. Meta-analysis of the literature. Br J Cancer. 2006;94:1823–32.

Brenner H, Hoffmeister M, Haug U. Should colorectal cancer screening start at the same age in European countries? Contributions from descriptive epidemiology. Br J Cancer. 2008;99:532–5.

Martins SF, Reis RM, Rodrigues AM, Baltazar F, Longatto-Filho A. Role of endoglin and VEGF family expression in colorectal cancer prognosis and anti-angiogenic therapies. World J Clin Oncol. 2011;10(2):272–80.

Parkin DM, Bray F, Ferlay J, Pisani P. Estimating the world cancer burden: Globocan 2000. Int J Cancer. 2001;94:153–6.

GLOBOCAN Factsheet Colorectal cancer estimated incidence, mortality and prevalence worldwide in 2012. 2012;Available at: http://globocan.iarc.fr/Pages/fact.

Roreno – Registo Oncológico Regional do Norte [homepage na internet]. Taxas de incidência de cancro na região Norte de Portugal; 2014. 2014;Available at: http://www.roreno.com.pt/pt/estatis.

Lambert DW, Wood IS, Ellis A, Shirazi-Beechey SP. Molecular changes in the expression of human colonic nutrient transporters during the transition from normality to malignancy. Br J Cancer. 2002;86(8):1262–9.

American Cancer Society. Cancer Facts & Figures 2013. Atlanta: American Cancer Society; 2013.

Neagoe A, Molnar A-M, Acalovschi M, Seicean A, Serban A. Risk factors for colorectal cancer: an epidemiologic descriptive study of a series of 333 patients. Rom J Gastroenterol. 2004;13(3):187–93.

Center MM, Jemal A, Smith RA, Ward E. Worldwide variations in colorectal Cancer. CA Cancer J Clin. 2009;59(6):366–78.

Jemal A, Bray F, Center MM, Ferlay J, Ward E, Forman D. Global cancer statistics. CA Cancer J Clin. 2011;61(2):69–90.

De Paoli P, Carbone A. Carcinogenic viruses and solid cancers without sufficient evidence of causal association. Int J Cancer. 2013;133(7):1517–29.

Bodaghi S, Yamanegi K, Xiao SY, et al. Colorectal papillomavirus infection in patients with colorectal cancer. Clin Cancer Res. 2005;11:2862–7.

Burnett-Hartman AN, Newcomb P, Potter JD. Infectious agents and colorectal cancer: a review of helicobacter pylori, Streptococcus bovis, JC virus, and human papillomavirus. Cancer Epidemiol Biomark Prev. 2008;17:2970–9.

Collins D, Hogan AM, Winter DC. Microbial and viral pathogens in colorectal cancer. Lancet Oncol. 2011;12:504–12.

Gornick MC, Castellsague X, Sanchez G, et al. Human papillomavirus is not associated with colorectal cancer in a large international study. Cancer Causes Control. 2010;21:737–43.

Baltzell K, Buehring GC, Krishamarty S, et al. Limited evidence of human papillomavirus in breast tissue using molecular in situ methods. Cancer. 2011;118:1212–20.

Kirgan D, Manalo P, Hall M, et al. Association of Human Papillomavirus and Colon neoplasms. Arch Surg. 1990;125:862–5.

Biesaga B, Janecka-Widła A, Kołodziej-Rzepa M, Słonina D, Darasz Z, Gasińska A. The prevalence of HPV infection in rectal cancer - report from south – Central Poland Cracow region. Pathol Res Pract. 2019 Sep;215(9):152513. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.prp.2019.152513.

Acknowledgements

Not applicable.

Funding

No funding support.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

SFM; VM; MR; ALF designed the structure of the study. VM ans ALF performed the DNA extraction and HPV analyses. SFM and MR performed rectal cancer surgery and are responsible for the CRC prospective data bases. SFM, VM and ALF wrote the final version of the manuscript. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

This study was conducted under compliance with the Declaration of Helsinki and was approved by the Ethics Committee of Hospital de Braga.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made. The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver (http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/) applies to the data made available in this article, unless otherwise stated.

About this article

Cite this article

Martins, S.F., Mariano, V., Rodrigues, M. et al. Human papillomavirus (HPV) 16 infection is not detected in rectal carcinoma. Infect Agents Cancer 15, 17 (2020). https://doi.org/10.1186/s13027-020-00281-z

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s13027-020-00281-z