Abstract

Background

Three amino acid differences between rodent and human APP affect medically important features, including β-secretase cleavage of APP and Aβ peptide aggregation (De Strooper et al., EMBO J 14:4932-38, 1995; Ueno et al., Biochemistry 53:7523-30, 2014; Bush, 2003, Trends Neurosci 26:207–14). Most rodent models for Alzheimer’s disease (AD) are, therefore, based on the human APP sequence, expressed from artificial mini-genes randomly inserted in the rodent genome. While these models mimic rather well various biochemical aspects of the disease, such as Aβ-aggregation, they are also prone to overexpression artifacts and to complex phenotypical alterations, due to genes affected in or close to the insertion site(s) of the mini-genes (Sasaguri et al., EMBO J 36:2473-87, 2017; Goodwin et al., Genome Res 29:494-505, 2019). Knock-in strategies which introduce clinical mutants in a humanized endogenous rodent APP sequence (Saito et al., Nat Neurosci 17:661-3, 2014) represent useful improvements, but need to be compared with appropriate humanized wildtype (WT) mice.

Methods

Computational modelling of the human β-CTF bound to BACE1 was used to study the differential processing of rodent and human APP. We humanized the three pivotal residues we identified G676R, F681Y and R684H (labeled according to the human APP770 isoform) in the mouse and rat genomes using a CRISPR-Cas9 approach. These new models, termed mouse and rat Apphu/hu, express APP from the endogenous promotor. We also introduced the early-onset familial Alzheimer’s disease (FAD) mutation M139T into the endogenous Rat Psen1 gene.

Results

We show that introducing these three amino acid substitutions into the rodent sequence lowers the affinity of the APP substrate for BACE1 cleavage. The effect on β-secretase processing was confirmed as both humanized rodent models produce three times more (human) Aβ compared to the original WT strain. These models represent suitable controls, or starting points, for studying the effect of transgenes or knock-in mutations on APP processing (Saito et al., Nat Neurosci 17:661-3, 2014). We introduced the early-onset familial Alzheimer’s disease (FAD) mutation M139T into the endogenous Rat Psen1 gene and provide an initial characterization of Aβ processing in this novel rat AD model.

Conclusion

The different humanized APP models (rat and mouse) expressing human Aβ and PSEN1 M139T are valuable controls to study APP processing in vivo allowing the use of a human Aβ ELISA which is more sensitive than the equivalent system for rodents. These animals will be made available to the research community.

Similar content being viewed by others

Background

Alterations in Aβ generation and aggregation are central to AD [1,2,3,4,5]. More than 177 transgenic models overexpressing mutated human APP and/or PSEN are currently available [6]. While these models lack tangles and do not develop symptoms of dementia, they remain good models in which to investigate mechanisms of amyloid accumulation. However, these models do have some drawbacks, including the potential artefacts directly caused by APP overexpression (for instance dysregulation of GABAergic neurotransmission [7]) and the random integration of transgenes (which could impact on the correct expression of adjacent genes) [8,9,10]. Recent improvements in genome editing now make it relatively straightforward to introduce subtle disease-causing mutations, or to humanize genes, rather than overexpressing mutant mini-genes [11].

APP knock-in models are available that express clinical AD mutations (KM 670/671NL, E693G, I716F) in the endogenous mouse sequence [12, 13]. These models develop amyloid pathology and interesting phenotypes without potential artefacts introduced by APP overexpression. However, the WT control (humanized APP without these mutations) is not readily available. The three amino acid substitutions (G676R, F681Y and R684H) needed to humanize the mouse Aβ sequence have a profound effect on Aβ generation [14].

In the current study we show, using in silico modelling, how these substitutions affect the interaction with BACE1. We have also used CRISPR-Cas9 technology to scarlessly humanize the endogenous Aβ sequence in the mouse and rat App genes [15] and investigate the effects on APP processing. We also created a PSEN1 knock-in mutation to generate a rat model for AD.

Material and methods

Mice

Mice Appem1Bdes with a humanized Aβ sequence (G676R, F681Y, R684H) were generated using CRISPR-Cas9 technology to target exon 16 of the mouse App gene. RNA guides were selected using the CRISPOR web tool. Guide 5′-GCAGAAUUCGGACAUGAUUC-3′ and 5′-GUCCGCCAUCAAAAACUGGU-3′ were selected and tested in mouse embryonic fibroblast (MEF) cells for cleaving efficiency. To promote homologous recombination directed repair [16] we made use of a ssODN repair template to mutate the target amino acids and to introduce two silent nucleotide substitutions. The first silent substitution destroys an EcoRI restriction cleaving site, facilitating genotyping. The second silent substitution prevents Cas9 cleaving the modified locus. Ribonucleoproteins (RNPs) containing 0.3 μM purified Cas9HiFi protein (Integrated DNA Technologies, IDT), 0.6 μM CRISPR RNAcrRNA, 0.6 μM trans activating crRNA (IDT) and 10 ng/μl ssODN (5′-tactttgtgtttgacgcagGTTCTGGGCTGACAAACATCAAGACGGAAGAGATCTCGGAAGTGAAGATGGATGCAGAATTtaGACATGATTCAGGATaTGAAGTCCaCCATCAgAAACTGgtaggcaaaaataaactgcctctccccgagattgcgtctggccagatgaaatacgtggcacctcgtggcttgtcctgtgt-3′) were injected into the pronucleus of 72 C57Bl6J embryos by microinjection in the Mouse Expertise Unit of KU Leuven. One positive pup was identified by PCR and restriction analysis. Sanger sequencing of App exon 16 region, as well as the 5 most likely off target sites predicted by the CRISPOR web tool, confirmed correct targeting (Additional file 1) and absence of spurious events at other sites. The founder mouse was backcrossed over two generations using C57BL6J mice before a homozygous colony was established, which was designated Apphu/hu. The strain is maintained on the original C57Bl6J background by backcrossing every 5th generation. Standard genotyping is performed by PCR with primers 5′-taggtggtggttaatggtt-3′ and 5′-cgtagctgcaacgttggact-3′ followed by digestion of the PCR product with EcoRI.

Apptm3.1Tcs [12] also known as App NL-G-F and Tg (Thy1-MAPT)22Schd [17] also known as Thy-Tau22 mice were used as positive controls during histological examination. Mice are kept on a C57Bl6J background and both females and males were included in the study. Mice are housed in cages enriched with wood wool and shavings as bedding, and given access to water and food ad libitum. All experiments were approved by the Ethical Committee for Animal Experimentation at the University of Leuven (KU Leuven).

Rats

As the rat is one of the most studied model organisms [18], and until recently no knock-in rat models of AD were available [19], we set out to humanize the Aβ sequence in rats using a similar strategy as we used in the mouse. Two gRNAs (Additional file 1), 5′-GUGAAGAUGGAUGCGGAGUU-3′ and 5′-UUUUGCAUACCAGUUUUUGA-3′, Cas9 mRNA and an oligo donor with targeting sequence (flanked by 120 bp homologous sequences on both sides) were co-injected into zygotes of Long Evans rats We also introduced the early-onset familial Alzheimer’s disease (FAD) mutation M139T [20] into the endogenous Rat Psen1 gene. To target Psen1. Cas9 mRNA, sgRNA 5′-GAUGACACUGAUCAUGAUGG-3′ and an oligo donor containing the ATG/ACC substitution with 120 bp homologous sequences were co-injected into zygotes (Additional file 2). F0 rats were genotyped after weaning using PCR and Sanger sequencing. Founder rats carrying the humanized Aβ sequence and M139T mutant allele were crossed twice with WT Long Evans rats (Charles River). Rats homozygous for the humanized APP KI were obtained after crossing heterozygous offspring. A breeding colony homozygous for the humanized Aβ sequence and heterozygous for the Psen1M139T allele was established and designated Apphu/hu;Psen1M139T. Standard genotyping for the APP KI mutation is done with the forward primer 5′-caTGATTCAGGCTaCGAAGTCCat-3′ and a common reverse primer 5′-CTCAGTGGTAATACGCCTGCCTAGC-3′. 5′-TGATTCAGGCTtCGAAGTCCgc-3′ is the forward primer for amplification of the wildtype App allele. For Psen1, genotyping is performed by PCR with a WT specific forward primer 5′-cgatcttgaatgccgccatcatg − 3′, or a M139T specific forward primer 5′-cgatcttgaatgccgccatcacc-3′, together with a common reverse primer 5′-ctgcacatgtacactctggcaag-3′. Rats are kept on a Long Evans background and backcrossed every fifth generation to WT rats. Both females and males were included in the study. Rats are housed in cages enriched with wood wool and shavings as bedding, and given access to water and food ad libitum. All experiments were approved by the Ethical Committee for Animal Experimentation at the University of Leuven (KU Leuven).

Human tissue samples

Human brain samples were resected from the lateral temporal neocortex and were obtained from patients who underwent amygdalohippocampectomy for medial temporal lobe seizures. Samples were collected at the time of surgery and immediately transferred to the laboratory for processing. All procedures were conducted according to protocols approved by the local Ethical Committee of KU Leuven (protocol number S61186).

Sample collection and protein analysis

Three female and 3 male mice and rats of the indicated genotypes were aged to 14 weeks and then euthanized by carbon dioxide overdose, followed by intracardial perfusion of ice-cold phosphate buffered saline. Brains were removed from the skull, and the cerebrum was snap frozen using liquid nitrogen and stored at − 70 °C until further processing. Half a brain hemisphere was weighed and homogenized in a bead mill using 5 volumes of buffer containing 20 mM Tris, 250 mM sucrose, 0.5 mM EDTA,0.5 mM EGTA (pH 7.4 HCl) supplemented with cOmplete™ protease inhibitor cocktail (Roche) and PhosSTOP™ (Sigma). This homogenate was divided in three fractions of 250 μl. One fraction was used to extract soluble Aβ using 0.4% Diethylamine treatment for 30 min at 4 °C. Following high speed clearing at 100,000 g for 1 h (at 4 °C), the sample was neutralized by adding 1/10 volume of 0.5 M Tris-HCl (pH 6.8) and analyzed by ELISA. To obtain the guanidine HCl (GuHCl)-soluble fraction, the 100,000 g pellet was washed with 0.4% Diethylamine before solubilization in 6 M GuHCl, 50 mM Tris-HCl (pH 7.6), supplemented with cOmplete™ protease inhibitor cocktail (Roche) and PhosSTOP™ (Sigma), and sonication using a micro-tip for 30 s at 10% amplitude (Branson). After incubation for 1 h at 25 °C with agitation (600 rpm), the sample was cleared by spinning at 100,000 g, diluted to 0.1 M GuHCl and analyzed by ELISA. Aβ38, Aβ40 and Aβ42 levels were quantified on Meso Scale Discovery (MSD) 96-well plates using ELISA and antibodies provided by Dr. Marc Mercken (Janssen Pharmaceutica). Monoclonal antibodies JRFcAβ38/5, JRFcAβ40/28 and JRFcAβ42/26, which recognize the C terminus of Aβ species terminating at amino acid 38, 40 or 42, respectively, were used as capture antibodies. JRF/rAβ/2 (rodent specific antibody) or JRFAβN/25 (human specific antibody) labeled with sulfo-TAG were used as the detection antibodies. Human Aβ43 was measured using the amyloid-beta (1–43) high sensitivity ELISA kit from IBL. To measure APP protein in the brain samples, 250 μl of homogenate were supplemented with 1% Triton X100, incubated for 30 min on ice and cleared for 30 min at 14,000 g (at 4 °C). For the extraction of soluble MAPT protein, 250 μl of a buffer containing 300 mM NaCl, 50 mM Tris-HCl, 150 mM NaCl, 1 mM EDTA, 2% NP-40, 0.5% sodium deoxycholate (pH 7.5), supplemented with cOmplete™ protease inhibitor cocktail (Roche) and PhosStop™ (Sigma), was added to 250 μl of brain homogenate. The sample was sonicated and incubated for 30 min on ice and cleared by centrifugation at 14,000 g (at 4 °C) for 30 min. When indicated, cell lysates were dephosphorylated after dialysis against 50 mM Tris-HCl (pH 7,6) using Calf Intestine Phosphatase (Bioke). Total protein content of the cell lysates was measured using a Biorad protein assay kit. Fifty micrograms of protein were loaded in reducing and denaturing conditions on NuPAGE™ (Thermo) gels and subjected to electrophoresis. Following separation, proteins were transferred to nitrocellulose membrane for western blotting. Membranes were blocked with 5% non-fat milk Tris buffered saline, containing 0.1% Tween 20, and incubated with the indicated primary antibodies, washed, and incubated with horseradish peroxidase conjugated secondary antibodies (Biorad). Blots were developed using the ECL Renaissance kit (Perkin Elmer). Primary antibodies used in this study were B63 (against the C-terminal amino acids of APP (previous used in [21], 1/1000)), 82E1 (IBL, 1/500), JRF/rAβ/2 (Janssen, 1/1000), anti-human TAU (Dako, 1/1000), anti-3RTAU (Millipore, 1/1000), anti-4RTAU (CosmoBio, 1/1000) and Anti-Actb clone AC-15 (Sigma, 1/20,000). Intensities of the bands were quantified with Aida/2D densitometry software.

All data are presented as mean ± SD, and were analyzed by GraphPad Prism 8. Unpaired two way Student’s t test and one-way ANOVA were used for group comparisons. P < 0.05 was considered statistically significant.

Histology

Rats and control mice were euthanized with an overdose of carbon dioxide and transcardially perfused with PBS. Brain tissue was subsequently harvested and post-fixed overnight in 4% PFA in PBS. Brains were cut in serial sections of 40 μm thickness with a vibrating microtome (Leica). For each sample, six series of sections were sequentially collected in free-floating conditions and permeabilized for 30 min with PBST (0.2% Triton X-100 in PBS) and blocked for 2 h with 5% normal donkey serum in PBST. Antigen retrieval was performed by boiling the sections for 1 min in 10 mM sodium citrate (pH 6) in a microwave. After three rinses with 0.1% Tween 20 in PBS, sections were incubated for 20 min with 10 μM X34 (Sigma) in 0.1% NaOH made in 40% Ethanol washed and incubated overnight at 4 °C with primary antibodies against Aβ: 82E1 (IBL, 1/150) or 6E10 (BioLegend, 1/200). The antibody stained sections were washed three times with 0.2% TritonX100-PBS and incubated with Alexa594 Donkey anti-mouse IgG (Thermo Fisher, 1/300) for 2 h at RT. After final washes with 0.2% TritonX100-PBS, sections were counterstained with TO-PRO (Thermo Fisher, 1/1000) and after three final washes were mounted on super frost microscope slides. Sections were visualized on a Nikon A1R Eclipse confocal system.

Computational model of the humanized β-CTF bound to BACE1

We have modelled the interaction of humanized β-CTF with BACE1, using as a template the published crystal structure of BACE1 in combination with an active site peptide inhibitor (PDB ID 5MCQ) [22]. The sequence of the humanized β-CTF was aligned to the peptide in 5MCQ, aligning residue E11 from the humanized β-CTF sequence to the STA query (Threonine) of the crystallized peptide (Fig. 1).

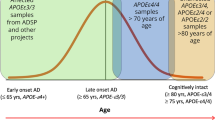

Model of humanized β-CTF bound to BACE1 and western blot analysis of mouse, rat and human APP. a Sequence alignment between the peptide inhibitor used in the crystal structure 5MCQ and the humanized β-CTF. Green: the three amino acids different between the human and rodent APP sequence. b The BACE structure is presented with its flap [22] in yellow and the 10S loop in orange; a model of rodent Aβ peptide is fitted. c Shows the same structure but now modelled with the humanized β-CTF. Two extra interactions between the G676R of the peptide and residue E326 and F681Y and residue N294 of BACE can be noted. d Western blot analysis of APP protein in the cerebrum of WT mouse (M), WT rat (R) and human (H), (n = 6). The B63 antibody, raised against the C-terminal part of APP, detects both full length APP (FL APP) and C-terminal fragments (CTF, longer exposure). β-ACTIN was used as the loading control. e Intensity-based quantification of full length APP, with values normalized to the human sample (n = 6, mean ± SD, **p = 0.0063 α-CTF/FL APP, **p = 0.0023 CTF/FL APP, *** p = 0.0002, ****p < 0.0001, One-Way ANOVA, Turkey post-hoc test)

Results

Humanized β-CTF provides a better substrate for BACE1

Three amino acid substitutions (G676R, F681Y and R684H) in the Aβ sequence decrease BACE1 processing of rodent APP compared to human APP [14]. We superposed the rodent and humanized β-CTF on a 21 amino acid peptide inhibitor at the binding site of BACE1 (Fig. 1), using the crystal structure PDB id:5MCQ [22]. The modeled binding modes reveal two important extra interactions of the humanized β-CTF with BACE1. G676R (replacing the glycine in the rodent sequence with arginine) provides a large positive charge that interacts with glutamate E326 of BACE1. F681Y introduces an extra -OH group, which acts as a hydrogen bond donor to N294 in BACE1. The two amino acids E326 and N294 of BACE1 require no reorganization or conformational change to make the interactions with the humanized β-CTF (Fig. 1).

We validated the different APP processing in human, mouse and rat brain by western blot analysis (Fig. 1). The ratio of β-CTF over full length APP in human samples is 4.8 (p < 0.0001 and 7.8 (p < 0.0001) times higher compared to mouse and rat, respectively, confirming that human APP is a better substrate for BACE1.

Processing of humanized Aβ APP in the rodent brain

We humanized the rodent APP genes (APPhu/hu, additional files 1 and 2) and analyzed brain homogenates by western blotting (Figs. 2 and 3). Full length APP and total APP-CTF levels were unchanged in humanized rat and mice, but APP-β-CTF signals increased 2.5 fold (p < 0.0001) and 4.2 fold (p = 0.009), respectively. Conversely, APP-α-CTF signals decreased 0.6 fold (p = 0.0067) and 0.7 fold (p = 0.0423) in APPhu/hu mice and rats. In mice, the Aβ40 levels in brain tissue rose from 2091 ± 130 pg/g in WT to 4827 ± 257 pg/g in the KI model (p < 0.0001), while in rats the levels were increased from 3302 ± 1256 pg/g in WT to 9292 ± 516 pg/g in the KI animals (p < 0.0001). The higher Aβ40 levels correlate with the fact that APP-β-CTF production in Apphu/hu rats, and basal Aβ generation in WT rats, are also higher than in the mice (Figs. 2 and 3). Soluble extracted total Aβ measured as the sum of Aβ38 + 40 + 42 raised the amounts measured to 7187 ± 1022 pg/g in the APPhu/hu mouse and 12,615 ± 1511 pg/g in the APPhu/hu rat. This is approximately half the concentration measured in control human brain, which was 21,141 ± 8712 pg/g.

Humanization of the Aβ sequence in mouse affects APP processing. a Western blot analysis of APP protein in the cerebrum of 14 weeks old WT and Apphu/hu mice (n = 6). B63 antibody detects full length APP (APP FL) and C-terminal fragments (CTF, longer exposure). 82E1 antibody specifically detects human Aβ1-22, and hence the human B-CTF, independently confirming that the mouse App gene was successfully humanized. β- ACTIN was used as loading control. b Quantification of APP protein in relative intensities (n = 6, mean ± SD, *** p < 0.0001 two tailed t-test). c ELISA analysis of soluble Aβ expressed as pg/g tissue. BD, below detection limit; ND, not determined (n = 6, mean ± SD, ***p < 0.0001 two tailed t-test). d Immunoblot of total MAPT in mouse cerebrum using the 3Rtau-specific antibody RD3, 4Rtau-specific antibody RD4 and an antibody against total tau. The MAPT ladder shows recombinant human MAPT (0N3R, 0N4R, 1N3R, 1N4R, 2N3R, 2N4R). Notice that mouse MAPT proteins migrate faster than the corresponding human splice variants. β- ACTIN was used as the loading control. e Quantification of MAPT relative to WT samples ((n = 6, mean ± SD)

Humanization of the Aβ sequence in rat affects APP processing, while the M139T mutation in PSEN1 results in increased Aβ42 production. a Western blot analysis of APP protein in cerebrum of 14 weeks old WT, Apphu/hu and Apphu/hu;Psen1M139T+/+ rats (n = 6). B63 antibody binds to full length APP (FL APP) and C-terminal fragments (CTF, longer exposure). 82E1 antibody specifically detects human Aβ (1-16), and hence the human B-CTF, independently confirming that the rat App gene was successfully humanized. β- ACTIN was used as a loading control. b Quantification of APP protein using relative intensity (n = 6, mean ± SD, ** p = 0.009, * p = 0.017, One-Way ANOVA, Turkey post-hoc test). c ELISA analysis of soluble Aβ expressed as pg/g tissue. BD, below detection limit; ND, not determined (n = 6, mean ± SD, *** p < 0.0001, * p = 0.012, One-Way Anova, Turkey post-hoc test). d Aβ ratios for Apphu/hu and Apphu/hu;Psen1M139T+/+ indicate an impairment in γ-secretase cleavage (n = 6, mean ± SD, ***p < 0.0001 two tailed t-test). e Immunoblot of total MAPT in rat cerebrum with the 3Rtau-specific antibody RD3, the 4Rtau-specific antibody RD4 and an antibody detecting total tau. The MAPT ladder shows recombinant human MAPT (0N3R, 0N4R, 1N3R, 1N4R, 2N3R, 2N4R). Notice that rat MAPT proteins migrate faster than the corresponding human splice variants. β- ACTIN was used as the loading control. f Quantification of MAPT relative to WT samples ((n = 6, mean ± SD)

M139T mutation in PSEN1 results in a shift in Aβ profile

The M139T FAD mutation [23] alters Aβ38/Aβ42 and Aβ42/Aβ40 ratios without affecting the endopeptidase cleaving activity responsible for release of the APP intracellular fragment [24]. This mutation is predicted not to interfere with Notch signaling [25], which we confirmed as Apphu/hu rats homozygous for the M139T FAD mutation are fertile and are indistinguishable from their PSEN WT littermates. Brain homogenates of Apphu/hu;Psen1M139T+/+ mice were analyzed (Fig. 3). The amounts of APP-CTF, APP-β-CTF and total Aβ measured as Aβ38 + 40 + 42 + 43 (11,898 ± 486 pg/g in Apphu/hu compared to 12,834 ± 676 pg/g in Apphu/hu;Psen1M139T+/+) are unaffected by the mutation. However, the mutation causes a relative shift towards more Aβ42 production, in parallel with a very small amount of Aβ43 and less Aβ40 (Fig. 3c). This results in an increased Aβ42/Aβ40 ratio (from 0.10 ± 0.01 to 0.27 ± 0.01) and a decreased Aβ38/Aβ42 ratio (2.60 ± 0.33 to 1.48 ± 0.25), indicating less efficient carboxypeptidase-like activity of the γ-secretase. This finding agrees with our previous in vitro work [24]. Unexpectedly, Aβ43 levels were reduced 2.5 times in the brains of homozygous Apphu/hu;Psen1M139T+/+ rats, resulting in an increased Aβ40/Aβ43 ratio (42.96 ± 6.39 to 92.41 ± 15.02). As total Aβ is unaffected by the mutation, the reduction of Aβ43 is not due to intracellular aggregation, indicating that the M139T mutation shifts APP processing towards the Aβ42 pathway [26]. Disappointingly, the oldest rat we examined (2 years of ages) did not show amyloid plaque pathology. We performed Aβ guanidine extractions on brain homogenates and confirm that there is no accumulation of insoluble Aβ in the mutant rats.

MAPT expression profile in rat is more complex compared to mouse

One of the reasons to generate a rat model for AD is that rat MAPT is claimed to be more similar to human MAPT, especially at the level of alternative splicing [27, 28]. 3RMAPT is indeed expressed at very low levels in mice (Fig. 2) and is easily detectable in rats. 4RMAPT is abundant in both species and higher mobility bands indicate the presence of 1N4R, 2N4R splice variants (Fig. 3), which become better visible after dephosphorylation (Additional file 3). Rodent MAPT, which is smaller, migrates faster compared to the human MAPT reference ladder. The estimated ratio of 3R to 4R MAPT is 1:13 in the rat brain, and thus very far removed from the 1:1 ratio in human brain. No tangle or plaque formation was observed until the age of 2 years. In single and double KI rats total MAPT and 4RMAPT protein levels are unchanged over time; the expression of the 3RMAPT isoform decreases and the Alzheimer’s disease-relevant AT100 phosphorylation, which is absent at 14 weeks of age in wildtype, single and double KI rats increases with age (Additional file 4). It seems unlikely that the rats will develop amyloid plaque or tangle pathology at a later age.

Discussion

We created mice and rats harboring a humanized Aβ sequence in the endogenous App gene. The models produce about three times more (human) Aβ compared to the WT rodent original strains, but this is still two times less than compared to humans. The rats and mice are suitable controls or starting points to study the effect of transgenes or knock-in mutations on APP processing. An advantage of these new models is that the human Aβ ELISAs routinely used in AD research can be used to study the different Aβ species.

We provide a first example of model utility by introducing the FAD mutation M139T into the endogenous Rat Psen1 gene. The PSEN1M139T mutation [20] leads to mean age of disease onset between 39 and 51 years old. Preclinical carriers have relatively high levels of Aβ42 in the cerebrospinal fluid [29]. In vitro this mutant affects the production rates of Aβ38 and Aβ40, while endopeptidase activity is not altered [24]. Our new data confirm these effects, but the strong lowering of Aβ43 and increase in Aβ40/Aβ43 ratio indicate that in vivo the mutation mainly works via a selective shift towards the Aβ42 product pathway and less via destabilization of the enzyme-substrate complex [30].

While our work was ongoing the group of LaFerla generated Apptm1.1Aduci mice via homologous recombination, introducing the humanized Aβ sequence into the endogenous App locus (JAX, Stock No: 032013). Recently, a knock-in rat model was also described by D’Adamio and colleagues [19, 31], which carries a humanized Aβ sequence and a KI of the PSEN1L435F mutation. The L435F mutation affects endopeptidase activity and, therefore, Notch signaling. Surprisingly, while the mutation is embryonically lethal in mice [32], homozygous rats are viable. No explanation for this interspecies difference is currently available [19]. These rats were also reported not to develop amyloid plaques, although it needs to be stated that animals were only followed up to 2 weeks of age.

The fact that our humanized rat model, incorporating a homozygous PSEN mutation, does not develop symptoms of AD at 2 years of age, despite highly pathological Aβ ratios, raises some tantalizing issues in respect to data obtained in the many overexpression models generated over the last 30 years to study AD. The amyloid plaques in these models seem critically dependent on strong overexpression of APP (and sometimes Presenilin). Such overexpression of proteins can lead to many artefacts. The fact that the simple introduction of the PSEN FAD mutations in the rodent homologues does not cause amyloid plaque formation, despite clear alterations in Aβ ratios, suggests that molecular and cellular events upstream and downstream of amyloid plaque formation in humans are lacking in rodents. Aging might be a major contributing effect, as the generation of amyloid plaques in humans spans several decades. Furthermore, it is increasingly recognized that the transition from biochemical accumulation of plaques to disease involves complex feedback loops between glial cells and amyloid plaques, which might be only partially mimicked in rodent brain [33].

Conclusion

In conclusion, the field should consider using knock-in techniques to introduce mutations or humanize genes when creating next generation models. Furthermore, knock-in of AD mutations in primates, or the use of human stem cells to generate organoids [34], or mouse-human chimeras [35,36,37], might provide additional ways to dissect the human molecular and cellular aspects of Alzheimer’s disease, moving the field forward.

Availability of data and materials

Apphu/hu mice and Apphu/hu;Psen1M139T rats will be made available upon request.

Abbreviations

- APP:

-

Amyloid precursor protein

- Aβ:

-

Amyloid beta peptide

- AD:

-

Alzheimer’s disease

- WT:

-

Wildtype

- CTF:

-

Carboxy terminal fragment

- BACE:

-

Beta-site amyloid precursor protein cleaving enzyme

- CRISPR:

-

Clustered Regularly Interspaced Short Palindromic Repeats

- Hu:

-

Humanized

- FAD:

-

Early-onset familial Alzheimer’s disease

- PSEN:

-

Presenilin

- ELISA:

-

Enzyme linked immunosorbent assays

- ssODN:

-

Single-stranded oligodeoxynucleotides

- RNP:

-

Ribonucleoprotein

- PCR:

-

Polymerase Chain Reaction

- MAPT:

-

Microtubule-Associated Protein Tau

- sgRNA:

-

Single guide RiboNucleic Acid

- KI:

-

Knock-in

- PFA:

-

Paraformaldehyde

- PBS:

-

Phosphate-buffered saline

- BDL:

-

Below detection limit

References

Center for Molecular Neurology [Internet]. [cited 2020 May 22]. Available from: https://uantwerpen.vib.be/ADMutations.

Jonsson T, Atwal JK, Steinberg S, Snaedal J, Jonsson PV, Bjornsson S, et al. A mutation in APP protects against Alzheimer’s disease and age-related cognitive decline. Nature. 2012;488(7409):96–9.

Rumble B, Retallack R, Hilbich C, Simms G, Multhaup G, Martins R, et al. Amyloid A4 protein and its precursor in down’s syndrome and Alzheimer’s disease. N Engl J Med. 1989;320(22):1446–52.

Ueno H, Yamaguchi T, Fukunaga S, Okada Y, Yano Y, Hoshino M, et al. Comparison between the aggregation of human and rodent amyloid β-proteins in GM1 Ganglioside clusters. Biochemistry. 2014;53(48):7523–30.

Bush AI. The metallobiology of Alzheimer’s disease. Trends Neurosci. 2003;26(4):207–14.

Alzheimer’s Disease Research Models | ALZFORUM [Internet]. [cited 2020 May 22]. Available from: https://www.alzforum.org/research-models/alzheimers-disease.

Rice HC, de Malmazet D, Schreurs A, Frere S, Van Molle I, Volkov AN, et al. Secreted amyloid-β precursor protein functions as a GABA(B)R1a ligand to modulate synaptic transmission. Science. 2019;363(6423):eaao4827.

Goodwin LO, Splinter E, Davis TL, Urban R, He H, Braun RE, et al. Large-scale discovery of mouse transgenic integration sites reveals frequent structural variation and insertional mutagenesis. Genome Res. 2019;29(3):494–505.

Gamache J, Benzow K, Forster C, Kemper L, Hlynialuk C, Furrow E, et al. Factors other than hTau overexpression that contribute to tauopathy-like phenotype in rTg4510 mice. Nat Commun. 2019;10(1):2479.

Sasaguri H, Nilsson P, Hashimoto S, Nagata K, Saito T, De Strooper B, et al. APP mouse models for Alzheimer’s disease preclinical studies. EMBO J. 2017;36(17):2473–87.

Wang H, Yang H, Shivalila CS, Dawlaty MM, Cheng AW, Zhang F, et al. One-step generation of mice carrying mutations in multiple genes by CRISPR/Cas-mediated genome engineering. Cell. 2013;153(4):910–8.

Saito T, Matsuba Y, Mihira N, Takano J, Nilsson P, Itohara S, et al. Single App knock-in mouse models of Alzheimer's disease. Nat Neurosci. 2014;17(5):661–3.

Reaume AG, Howland DS, Trusko SP, Savage MJ, Lang DM, Greenberg BD, et al. Enhanced amyloidogenic processing of the beta-amyloid precursor protein in gene-targeted mice bearing the Swedish familial Alzheimer’s disease mutations and a “humanized” Abeta sequence. J Biol Chem. 1996;271(38):23380–8.

De Strooper B, Simons M, Multhaup G, Van Leuven F, Beyreuther K, Dotti CG. Production of intracellular amyloid-containing fragments in hippocampal neurons expressing human amyloid precursor protein and protection against amyloidogenesis by subtle amino acid substitutions in the rodent sequence. EMBO J. 1995;14(20):4932–8.

Vanden Berghe T, Hulpiau P, Martens L, Vandenbroucke RE, Van Wonterghem E, Perry SW, et al. Passenger mutations confound interpretation of all genetically modified congenic mice. Immunity. 2015;43(1):200–9.

Paquet D, Kwart D, Chen A, Sproul A, Jacob S, Teo S, et al. Efficient introduction of specific homozygous and heterozygous mutations using CRISPR/Cas9. Nature. 2016;533(7601):125–9.

Schindowski K, Bretteville A, Leroy K, Begard S, Brion J-P, Hamdane M, et al. Alzheimer’s disease-like tau neuropathology leads to memory deficits and loss of functional synapses in a novel mutated tau transgenic mouse without any motor deficits. Am J Pathol. 2006;169(2):599–616.

Gill TJ, Smith GJ, Wissler RW, Kunz HW. The rat as an experimental animal. Science. 1989;245(4915):269–76.

Tambini MD, D’Adamio L. Knock-in rats with homozygous PSEN1L435F Alzheimer mutation are viable and show selective γ-secretase activity loss causing low Aβ40/42, high Aβ43. J Biol Chem. 2020;295(21):7442–51.

Campion D, Flaman J-M, Brice A, Hannequin D, Dubois B, Martin C, et al. Mutations of the presenilin I gene in families with early-onset Alzheimer’s disease. Hum Mol Genet. 1995;4(12):2373–7.

Esselens G, Oorschot V, Baert V, Raemaekers T, Spittaels K, Serneels L, et al. Presenilin 1 mediates the turnover of telencephalin in hippocampal neurons via an autophagic degradative pathway. J Cell Biol. 2004;166(7):1041.

Ruderisch N, Schlatter D, Kuglstatter A, Guba W, Huber S, Cusulin C, et al. Potent and selective BACE-1 peptide inhibitors lower brain Aβ levels mediated by brain shuttle transport. EBioMedicine. 2017;24.

PSEN1 M139T | ALZFORUM [Internet]. [cited 2020 May 22]. Available from: https://www.alzforum.org/mutations/psen1-m139t.

Szaruga M, Veugelen S, Benurwar M, Lismont S, Sepulveda-Falla D, Lleo A, et al. Qualitative changes in human γ-secretase underlie familial Alzheimer’s disease. J Exp Med. 2015;212(12):2003–13.

De Strooper B, Annaert W, Cupers P, Saftig P, Craessaerts K, Mumm JS, et al. A presenilin-1-dependent γ-secretase-like protease mediates release of Notch intracellular domain. Nature. 1999;398(6727):518–22.

Takami M, Nagashima Y, Sano Y, Ishihara S, Morishima-Kawashima M, Funamoto S, et al. γ-Secretase: Successive tripeptide and tetrapeptide release from the transmembrane domain of β-carboxyl terminal fragment. J Neurosci. 2009;29(41):13042–52.

Hanes J, Zilka N, Bartkova M, Caletkova M, Dobrota D, Novak M. Rat tau proteome consists of six tau isoforms: implication for animal models of human tauopathies. J Neurochem. 2009;108(5):1167–76.

Cohen RM, Rezai-Zadeh K, Weitz TM, Rentsendorj A, Gate D, Spivak I, et al. A transgenic Alzheimer rat with plaques, tau pathology, behavioral impairment, oligomeric Aβ, and frank neuronal loss. J Neurosci. 2013;33(15):6245–56.

Portelius E, Fortea J, Molinuevo JL, Gustavsson MK, Andreasson U, Sanchez-Valle R. The amyloid-β isoform pattern in cerebrospinal fluid in familial PSEN1 M139T- and L286P-associated Alzheimer’s disease. Mol Med Rep. 2012;5(4):1111–5.

Szaruga M, Munteanu B, Lismont S, Veugelen S, Horré K, Mercken M, et al. Alzheimer’s-causing mutations shift Aβ length by destabilizing γ-secretase-Aβn interactions. Cell. 2017;170(3):443–56.

Tambini MD, Yao W, D’Adamio L. Facilitation of glutamate, but not GABA, release in familial Alzheimer’s APP mutant Knock-in rats with increased β-cleavage of APP. Aging Cell. 2019;18(6):e13033.

Xia D, Watanabe H, Wu B, Lee SH, Li Y, Tsvetkov E, et al. Presenilin-1 Knockin mice reveal loss-of-function mechanism for familial Alzheimer’s disease. Neuron. 2015;85(5):967–81.

De Strooper B, Karran E. The cellular phase of Alzheimer’s disease. Cell. 2016;164(4):603–15.

Arber C, Lovejoy C, Wray S. Stem cell models of Alzheimer’s disease: progress and challenges. Alzheimers Res Ther. 2017;9(1):42.

Espuny-Camacho I, Arranz AM, Fiers M, Snellinx A, Ando K, Munck S, et al. Hallmarks of Alzheimer’s disease in stem-cell-derived human neurons transplanted into mouse brain. Neuron. 2017;93(5):1066–81.

Mancuso R, Van Den Daele J, Fattorelli N, Wolfs L, Balusu S, Burton O, et al. Stem-cell-derived human microglia transplanted in mouse brain to study human disease. Nat Neurosci. 2019;22(12):2111–6.

Abud EM, Ramirez RN, Martinez ES, Healy LM, Nguyen CHH, Newman SA, et al. iPSC-derived human microglia-like cells to study neurological diseases. Neuron. 2017;94(2):278–93.

Acknowledgements

We thank Veronique Hendrickx and Jonas Verwaeren for animal husbandry, Adel Charbel Khoudary for discussion and Zhiyong Zhang for performing the zygote injections.

Funding

Work in the laboratory of B.D.S. was supported by the European Union (grant no. ERC-834682 CELLPHASE_AD), the Fonds voor Wetenschappelijk Onderzoek, KU Leuven, Flanders Institute for Biotechnology, UK Dementia Research Institute (Medical Research Council, Alzheimer’s Research UK and Alzheimer’s Society), a Methusalem grant from KU Leuven and the Flemish Government, the ‘Geneeskundige Stichting Koningin Elisabeth’, Opening the Future campaign of the Leuven Universitair Fonds, the Belgian Alzheimer Research Foundation and the Alzheimer’s Association USA. B.D.S. is holder of the Bax-Vanluffelen Chair for Alzheimer’s disease.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

LS, DT, and BDS conceived and designed the study and wrote the manuscript. LS and DT performed experiments. PBL performed computational modelling. TT provided human brain tissue from surgically resected samples from epilepsy patients. MGH participated in discussions and manuscript preparation. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Authors’ information

Not applicable.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval

All animal experiments were conducted according to protocols approved by the local Animal Ethical Committee of the KU Leuven (governmental license LA1210579), which adheres to local governmental and EU guidelines. All procedures with human brain tissue were conducted according to protocols approved by the local Ethical Committee overseeing the use of human .samples (protocol number S61186).

Consent for publication

All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Competing interests

The authors report no competing interests. Bart de Strooper is, or has been, a consultant for pharmaceutical companies, including Jansen Pharmaceuticals and Eisai.

Additional information

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary information

Additional file 1: Generation of APP KI mice and rats using CRISPR-Cas (A)

The top panel displays an alignment between human Aβ and rodent Aβ peptides. Differences are indicated in red, boxes represent transmembrane domains. The lower panel depicts the genomic organization and sequence (exon 16) for both the mouse and rat App genes. Exons are indicated as black boxes, arrows denote primers used for genotyping and sequencing. Underlined sequences were targeted with CRISPR guides; ssODN represent the templates used for homologous recombination. Nucleotides and amino acids indicated in red are the target sequences, nucleotides in green are silent mutations introduced to prevent Cas9 recutting after homologous recombination. (B) Sanger sequencing results confirmed the introduction of the point mutations in one strand as shown above the chromatograms. (C) PCR analysis of APP KI mice. The digest pattern produced by EcoRI indicates the presence of the KI allele, as the restriction site is destroyed after gene editing.

Additional file 2: Generation of M139T

Psen1 KI rats by CRISPR-Cas. (A) Partial sequence of exon 5 of the rat Psen1 gene. Underlined sequences indicate the CRISPR guide CRISPR; ssODN represent the template used for homologous recombination. Nucleotides and amino acids indicated in red are the target sequences. (B) Sanger sequencing results confirmed the introduction of the point mutations (underlined).

Additional file 3: Comparing MAPT splice isoforms between mouse and rat.

Analysis of MAPT isoforms after dephosphorylation with alkaline phosphatase (AP). Cerebrum extracts were treated with (+) or without (−) alkaline phosphatase (AP) at 37 °C for 1h and immunoblotted with a 3Rtau-specific antibody RD3, the 4Rtau-specific antibody RD4 and an antibody detecting total MAPT. The middle lane is recombinant human MAPT (ladder). Mice express mainly the 0N4R splice variant compared to the more complex expression pattern in rat brain lysates, which contain all 6 splice forms. The estimated ratio 3R/4R MAPT = 1/13.

Additional file 4: MAPT protein analysis in two year old rats.

Immunoblot of MAPT in the cerebrum with total tau antibody, 3Rtau-specific antibody RD3, 4Rtau-specific antibody RD4 and phospho-tau antibodies AT270 and AT100 of two year old rats (n=2). LE rats* are cerebrum samples from wildtype Long Evans rats aged 14 weeks. MAPT ladder is recombinant human MAPT (0N3R, 0N4R, 1N3R, 1N4R, 2N3R, 2N4R). Notice that mouse MAPT proteins migrating faster than the corresponding human splice variants.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/. The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver (http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/) applies to the data made available in this article, unless otherwise stated in a credit line to the data.

About this article

Cite this article

Serneels, L., T’Syen, D., Perez-Benito, L. et al. Modeling the β-secretase cleavage site and humanizing amyloid-beta precursor protein in rat and mouse to study Alzheimer’s disease. Mol Neurodegeneration 15, 60 (2020). https://doi.org/10.1186/s13024-020-00399-z

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s13024-020-00399-z