Abstract

Background

TREM2 is a transmembrane receptor that is predominantly expressed by microglia in the central nervous system. Rare variants in the TREM2 gene increase the risk for late-onset Alzheimer’s disease (AD). Soluble TREM2 (sTREM2) resulting from shedding of the TREM2 ectodomain can be detected in the cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) and is a surrogate measure of TREM2-mediated microglia function. CSF sTREM2 has been previously reported to increase at different clinical stages of AD, however, alterations in relation to Amyloid β-peptide (Aβ) deposition or additional pathological processes in the amyloid cascade (such as tau pathology or neurodegeneration) remain unclear. In the current cross-sectional study, we employed the biomarker-based classification framework recently proposed by the NIA-AA consensus guidelines, in combination with clinical staging, in order to examine the CSF sTREM2 alterations at early asymptomatic and symptomatic stages of AD.

Methods

A cross-sectional study of 1027 participants of the Alzheimer’s Disease Imaging Initiative (ADNI) cohort, including 43 subjects carrying TREM2 rare genetic variants, was conducted to measure CSF sTREM2 using a previously validated enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA). ADNI participants were classified following the A/T/N framework, which we implemented based on the CSF levels of Aβ1-42 (A), phosphorylated tau (T) and total tau as a marker of neurodegeneration (N), at different clinical stages defined by the clinical dementia rating (CDR) score.

Results

CSF sTREM2 differed between TREM2 variants, whereas the p.R47H variant had higher CSF sTREM2, p.L211P had lower CSF sTREM2 than non-carriers. We found that CSF sTREM2 increased in early symptomatic stages of late-onset AD but, unexpectedly, we observed decreased CSF sTREM2 levels at the earliest asymptomatic phase when only abnormal Aβ pathology (A+) but no tau pathology or neurodegeneration (TN-), is present.

Conclusions

Aβ pathology (A) and tau pathology/neurodegeneration (TN) have differing associations with CSF sTREM2. While tau-related neurodegeneration is associated with an increase in CSF sTREM2, Aβ pathology in the absence of downstream tau-related neurodegeneration is associated with a decrease in CSF sTREM2.

Similar content being viewed by others

Background

The triggering receptor expressed on myeloid cells 2 (TREM2) is an innate immune receptor that is expressed on the plasma membrane of microglia in the central nervous system (CNS) [1]. TREM2 is involved in key functions of microglia including phagocytosis, cytokine release, lipid sensing and microglia proliferation and migration [2,3,4,5,6]. TREM2 mutations strongly increase the risk of developing Alzheimer’s disease (AD) [7, 8] and other neurodegenerative diseases including frontotemporal dementia (FTD), Parkinson’s disease and amyotrophic lateral sclerosis [9,10,11,12]. Furthermore, homozygous loss-of-function mutations in TREM2 are sufficient to cause Nasu-Hakola disease (NHD) and FTD-like syndrome [13, 14]. Together, this suggests that abnormal TREM2 function plays an essential role across different neurodegenerative diseases.

TREM2 is a type-1 transmembrane protein that matures within the secretory pathway and its ectodomain is shed at the plasma membrane [2, 15]. Soluble TREM2 (sTREM2) accumulates in conditioned media of cultured cells and in biological fluids such as plasma and cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) [2, 16]. Shedding is mediated by ADAM10 and 17 C-terminal to histidine 157 [2, 15, 17,18,19]. Homozygous mutations causing NHD or FTD-like syndrome (such as p.T66M) retain misfolded TREM2 in the endoplasmic reticulum, preventing its maturation and its cleavage on the plasma membrane. Patients bearing these mutations have undetectable levels of sTREM2 in CSF and blood [2, 20, 21].

The fact that TREM2 is selectively expressed in microglia in the CNS and is associated with AD and neurodegeneration, let us hypothesize that sTREM2 in CSF may be a marker for microglia function and its response to Aβ and tau pathology and neurodegeneration. Specifically, sTREM2 may reflect the amount of signaling competent TREM2 on the surface of activated microglia. This idea is supported by the fact that the levels of sTrem2 in the brain of an Aβ mouse model correlate with TSPO small animal positron emission tomography (μPET) signal [22], a marker of microglial activation, and the fact that a knock-in mouse model bearing the Trem2 p.T66M mutation has decreased microglial activity [20].

We and others have previously reported changes in the levels of CSF sTREM2 in AD compared to controls [2, 21, 23,24,25,26]. Specifically, we found a disease-stage dependent increase in CSF sTREM2 peaking within the early symptomatic stages of late-onset AD [25]. In autosomal dominant AD (ADAD) assessed within the Dominantly Inherited Alzheimer Network (DIAN) project [26], we demonstrated that CSF sTREM2 was increased in mutation carriers compared to non-carriers five years before the estimated years from symptom onset (EYO), but with a considerable delay after the development of Aβ pathology, which emerged about 10-15 years earlier. Together, these studies suggest a complex association of CSF sTREM2 as a function of disease evolution, in which CSF sTREM2 dynamically changes as disease progresses and reaches its highest levels between the later asymptomatic and earlier symptomatic stages, when neurodegeneration has already started.

An important unanswered question in this regard concerns the association between CSF sTREM2 and primary pathologies including Aβ and tau deposition, as well as neurodegeneration during the course of AD. Therefore, we used herein the biomarker-based A/T/N classification system [27], which is the foundation of the recently proposed 2018 NIA-AA research Framework [28]. This classification system consists of three biomarker dimensions including the assessment of Aβ pathology (A), tau pathology (T), and neurodegeneration (N). In the present study, we investigated CSF sTREM2 levels at different AD biomarker-defined groups following the A/T/N classification and the clinical stage (as defined by the clinical dementia rating score, CDR) in participants of the well-characterized ADNI study. This approach allowed us to test the two main aims of this study. First, to assess the association of CSF sTREM2 with Aβ pathology and its downstream pathological processes (i.e. tau pathology and neurodegeneration). Second, to assess the changes on CSF sTREM2 that occur in the Alzheimer’s continuum and hence replicate ours and others findings in the ADNI cohort [23,24,25,26, 29].

Methods

ADNI Participants and study design

This is a cross-sectional study in which CSF sTREM2 was measured in 1031 participants of the ADNI project. Among them, 4 individuals did not have the AD core biomarkers measurements and were further excluded from the analysis, rendering a study sample of 1027 subjects. The CSF sTREM2 measurements were uploaded to the ADNI database (http://adni.loni.usc.edu) on 16/03/2018 and the data used in this study was downloaded on 21/03/2018. The ADNI project (http://www.loni.usc.edu/) is a multicenter longitudinal study led by Principal Investigator Michael W Weiner with the main goal to develop and validate biomarkers for subject selection and as surrogate outcome measures in late-onset AD [30]. The institutional review boards (IRB) of all participating centers approved the procedures of the study and all participants or surrogates provided informed consent. Our local IRB (LMU) also approved the study.

Clinical classification

In line with the recently published 2018 NIA-AA “research framework” for the diagnosis of Alzheimer’s disease [28], we assigned each ADNI participant in a group defined by its biomarker profile, as described by the A/T/N scheme [27], coupled with its cognitive status, as defined by the CDR score [31]. The A/T/N scheme comprises 3 biomarker groups: “A” refers to aggregated Aβ, “T” aggregated tau and “N” to neurodegeneration. Each biomarker group is binarizied in negative (-) or positive (+) based on whether their biomarkers are normal or abnormal. In the present study, we assigned “A+” to those individuals that had a CSF Aβ1-42 < 976.6 pg/ml, “T+” to those individuals with P-tau181P > 21.8 pg/ml and “N+” to those individuals with T-tau > 245 pg/ml. We merged the aggregated tau (T) and neurodegeneration (N) groups in order to decrease the number of groups to be compared. TN negative (TN-) was defined as having both the aggregated tau (T) and neurodegeneration (N) biomarkers in the normal range (T- and N-, that is P-tau181P ≤ 21.8 pg/ml and T-tau ≤ 245 pg/ml). Participants were classified as TN positive (TN+) if either aggregated tau (T) or neurodegeneration (N) were abnormal (T+ or N+, that is P-tau181P > 21.8 pg/ml or T-tau > 245 pg/ml). Only 5.4% of the individuals of the total differed between the T and N biomarkers groups.

The combination of the biomarker profile (A/T/N scheme) and the clinical status (CDR) rendered 12 different groups that are displayed in Table 1. We studied CSF sTREM2 in ADNI following two approaches. In a first one, we compared CSF sTREM2 between the different A/T/N categories within each clinical stage. In a second one, we attempted to model the course of AD with biomarker and clinical-based groups, similar to what was proposed by the 2011 NIA-AA criteria [32,33,34]. Thus, in this second approach, we compared the ‘CDR = 0 A-/TN-’ group (which corresponds to healthy controls) with those biomarker-based groups that fall into the Alzheimer’s continuum category, that is: ‘Preclinical AD A+/TN-’, ‘Preclinical AD A+/TN+’, ‘AD CDR = 0.5’ and ‘AD CDR = 1’. Since our aim was to study the Alzheimer's continuum, we excluded from this analysis those individuals that fall in the category of suspected non-Alzheimer’s pathology (SNAP) [35,36,37,38] and those symptomatic individuals (CDR > 0) that do not have positive biomarkers for both Aβ deposition (CSF Aβ1-42) and neurodegeneration/tau pathology (T-tau or P-tau181P).

Alzheimer’s disease CSF core biomarkers and CSF sTREM2 measurements

In the present study, we used the AD CSF core biomarkers measurements performed with the Elecsys® total-tau CSF, the Elecsys® phosphotau(181P) CSF and the Elecsys® β-amyloid(1–42) CSF immunoassays on a cobas e 601 instrument [39, 40]. The data is available in the ‘UPENNBIOMK9.csv’ file in the ADNI database. These immunoassays are for investigational use only. They are currently under development by Roche Diagnostics and not commercially available yet. The analyte measuring ranges (lower technical limit to upper technical limit) of these assays are the following: 80 to 1300 pg/ml for total-Tau CSF, 8 to 120 pg/ml for phosphor-Tau(181P) CSF, and 200 to 1700 pg/ml for Elecsys® β-Amyloid(1-42) CSF immunoassays. The measuring range of the Elecsys® β-Amyloid(1-42) CSF immunoassay beyond the upper technical limit has not been formally established. Therefore use of values above the upper technical limit, which are provided based on an extrapolation of the calibration curve, is restricted to exploratory research purposes and is excluded for clinical decision making or for the derivation of medical decision points.

CSF sTREM2 measurements were done with a MSD platform-based assay, previously reported and validated [2, 25, 26]. A comprehensive description of the assay is shown in Supplementary methods (see Additional file 1: Supplementary methods). The CSF sTREM2 measurements are publicly available in the ADNI database.

Cell culture and transient transfection of HEK293T cells

HEK293T cells were cultured in DMEM with Glutamax I supplemented with 10 % (v/v) fetal calf serum (FCS) and 1 % penicillin/streptomycin. 24 hours after seeding, cells were transiently transfected with equal amounts of DNA coding for the different TREM2 variants using Lipofectamine 2000 as the transfection reagent. TREM2 variant constructs were generated by site-directed mutagenesis (Stratagene) of a TREM2 wt construct bearing N- and C-terminal HA and FLAG tags, respectively, as previously described [2]. All constructs were verified by DNA sequencing (GATC Biotech). We collected the conditioned media 48 hours after transfection. Cellular debris was removed by centrifugation at 4°C (13300 rpm, 20 min). Supernatants were subsequently frozen at -20°C until analyses were performed. Cell culture reagents were purchased from Thermo Fisher Scientific unless otherwise noted.

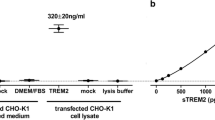

We measured the concentrations of HA-labeled TREM2 protein in the HEK293T conditioned media by two different ELISAs. First, sTREM2 concentrations were determined by the same ELISA used to measured sTREM2 in the human CSF samples, which includes a detection antibody against sTREM2 (see Additional file 1: Supplementary methods). Second, it was measured by a MSD platform-based including an antibody against the HA-tag. This second assay follows the same protocol as the first one but with the following modifications. The detection antibody is a monoclonal rat IgG anti-HA peptide sequence (YPYDVPDYA), clone 3F10 (Roche, Cat. No. 11 867 423 001; 100 ng/mL, 50 μL/well); the secondary antibody is a SULFO-TAG-labeled goat polyclonal anti-rat IgG antibody (MSD, Cat. no. R32AH-1; 0.5 μg/mL, 25 μL/well). The samples were diluted 1:50 and 1:100 in assay buffer [0.25% BSA and 0.05% Tween 20 in PBS (pH = 7.4)], supplemented with protease inhibitors (Sigma; Cat. no. P8340) and measured in duplicates for each dilution. We acquired the electrochemiluminescence response values using the MESO QuickPlex SQ 120. We compared the signal of the sTREM2 ELISA with that of the HA-tag assay for each of the TREM2 rare variants. The percentage between these two assays renders a relative affinity of the sTREM2 ELISA to each of the TREM2 rare variants in relation to its respective HA-tag control.

Statistical analysis

CSF sTREM2 did not follow a normal distribution (Kolmogorov-Smirnov test: P < 0.0001) and were hence log10-transformed. After transformation, CSF sTREM2 followed a normal distribution as assessed by Kolmogorov-Smirnov test (P = 0.200) and visual inspection of the histogram. All the statistical analysis described in this study are performed with the log10-transformed values.

A one-way analysis of covariance (ANCOVA) was conducted to determine statistically significant differences on CSF sTREM2 between TREM2 rare variants carriers and the non-carriers’ individuals adjusting for the effect of age, followed by a Bonferroni corrected post hoc pairwise comparison. Only those groups of TREM2 rare variants carriers that comprise more than 1 subject were included in the analysis.

The following analyses were conducted excluding outliers’ values of CSF sTREM2, defined as values differing 3 standard deviations from the mean. There were 5 outliers: 2 subjects classified as ‘Preclinical AD A+TN-’ (1 a TREM2 rare variant carrier and 1 a non-carrier), 1 classified as ‘CDR = 0.5 A+TN-’ (TREM2 rare variant carrier), 1 classified as ‘AD CDR = 0.5’ (TREM2 rare variant carrier), 1 classified as ‘AD CDR = 1’ (non-carrier). Including or excluding these outliers do not change the findings of this study.

To study the association of CSF sTREM2 with demographic and genetic data, we computed a linear regression model with CSF sTREM2 as an outcome variable and age, gender and APOE ε4 status as fixed effects. Since only age showed to be a significant predictor of CSF sTREM2, the following analyses were conducted including only age as a covariate.

To test the differences in CSF sTREM2 across biomarker profiles in the A/T/N framework, we applied a one-way ANCOVA including age as covariate, followed by Bonferroni corrected post hoc pairwise comparisons. A similar approach was used to test whether CSF sTREM2 changes across the Alzheimer’s continuum. These analyses were performed including or excluding individuals carrying a TREM2 rare variant and yielded similar results.

Finally, we studied the association between CSF sTREM2 and each of the CSF core biomarkers for AD (T-tau, P-tau181P, Aβ1-42) with a multiple linear regression adjusted for age. The analysis was conducted separately in the healthy controls, Alzheimer’s continuum and SNAP groups. We performed the analysis both including or excluding outliers (defined as AD CSF core biomarkers 3 standard deviations below or above the group mean) in order to exclude that the associations were driven by extreme values. The analysis with and without outliers rendered similar results. For CSF Aβ1-42, the analyses were performed using both the truncated values at the upper technical limit and the exploratory measurements available based on the extrapolation of the calibration curve. In the main text, we report the results using the extrapolated measurements, but using the truncated ones yielded similar results.

Statistical analysis was performed in SPSS IBM, version 20.0, and the free statistical software R (http://www.r-project.org/). Figures were built using GraphPad Prism or free statistical software R. All tests were 2-tailed, with a significance level of α = 0.05.

Results

Association of CSF sTREM2 with genetic and demographical data

We studied a total of 1027 participants of the ADNI study. The demographical and clinical characteristics of the whole study population are described in Table S1 (see Additional file 1). Among the participants studied, 43 (4.2 %) had a known TREM2 rare variant (see reference [41] for a comprehensive review of the pathogenicity of each variant). The overall mean levels of CSF sTREM2 of these individuals (M = 3913 pg/ml, SD = 3548, n = 43) were significantly lower than the rest of ADNI participants without a TREM2 rare variant (M = 4136 pg/ml, SD = 2171, n = 984; F1,1024 = 6.77, P = 0.009, ηp2 = 0.007; Table 2, Fig. 1) in a one-way ANCOVA adjusted for age. However, CSF sTREM2 varied considerably between TREM2 variants (F4,1019 = 8.79, P < 0.0001, ηp2 = 0.033) and Bonferroni’s post hoc comparisons test indicated that the p.R47H variant [7,8,9,10,11,12] had significantly higher CSF sTREM2 (P = 0.003) and the p.L211P variant [42, 43] significantly lower CSF sTREM2 (P = 0.002) than non-carriers. No differences in CSF sTREM2 were found between individuals with a p.R62H [44, 45] and the p.D87N [7] variants and the non-carriers. There was a single subject carrying both a p.D87N and p.R62H variants, and another single subject carrying a p.H157Y variant, which were not included in the statistical analysis. However, it is worth noting that the subject carrying a p.H157Y TREM2 rare variant had relatively high CSF sTREM2 (Table 2, Fig. 1), an observation that agrees with our previous findings that the p.H157Y variant, which is located exactly at the cleavage site, increases shedding of TREM2 [17]. Given that TREM2 rare variants may influence CSF sTREM2 (as described here and in [24]), all the following analyses are excluding participants carrying these rare variants. Nevertheless, including the TREM2 rare variants carriers did not change the results. In order to test whether the differences in CSF sTREM2 among TREM2 rare variants are influenced by differences in the antibody affinity to the mutant sTREM2, we transfected HEK293T cells with an epitope tagged wild type (wt) and mutated TREM2 and measured sTREM2 released in the media with the same ELISA used for the quantification of CSF sTREM2 and with an ELISA using an antibody against the epitope tag (Additional file 1: Figure S1). This revealed that the p.R47H, p.R62H and p.H157Y TREM2 rare variants were detected with a slightly reduced efficiency in our ELISA; therefore, the increased levels of CSF sTREM2 found in subjects bearing the p.R47H rare variants are even slightly underestimated. On the other hand, the p.L211P TREM2 rare variants were detected efficiently, independently of their individual amino acid exchanges. However, the p.D87N TREM2 rare variant was detected with significant less affinity in our ELISA than using the antibody against the epitope tag. Thus, the decreased CSF sTREM2 found in the p.D87N rare variant should be interpreted with caution.

CSF sTREM2 in ADNI participants carrying a TREM2 rare variant.

Scatter plot representing the levels of CSF sTREM2 in carriers of a TREM2 rare variant, compared to the non-carriers ADNI participants. Solid bars represent the mean and the standard deviation (SD). P-values were assessed by a one-way ANCOVA adjusted for age, followed by Bonferroni corrected post hoc pairwise comparisons between the TREM2 variants carriers’ groups and the non-carriers. We did not include in the comparison those rare variants with only one subject (p.R62H/p.D87N and p.H157Y).

In the sample excluding the TREM2 rare variants carriers and TREM2 outliers’ values (n = 982, see methods section), we first assessed which demographic and genetic variables are associated with CSF sTREM2 (descriptives summarized in Table 3). Consistent with previous results [21, 23,24,25,26], CSF sTREM2 levels were associated with age (β = +0.275, P < 0.0001, ηp2 = 0.073), but not with gender (F1,978 = 0.029, P = 0.866, ηp2 = 0.00003) or APOE ε4 status (F1,978 = 0.099, P = 0.753, ηp2 = 0.0001). Consequently, all further analysis included age as a covariate, but not gender or APOE ε4 status.

Differences of CSF sTREM2 within the A/T/N classification of AD

In order to assess the impact of Aβ deposition or the downstream processes of the amyloid cascade (i.e. tau pathology and neurodegeneration), we applied the recently proposed A/T/N classification framework of AD, which proposes 3 binary biomarker groups [27]: (1) aggregated Aβ (A+/A-), (2) aggregated tau (T+/T-) and (3) neurodegeneration (N+/N-). Given that CSF T-tau and CSF P-tau181P were highly correlated, we merged the tau (T) and neurodegeneration (N) groups. ‘TN-’ profile was defined as both CSF P-tau181P and T-tau within the normal range, whereas ‘TN+’ was defined as abnormal levels of CSF P-tau181P or T-tau. Thus, we compared 4 different biomarker profiles within each clinical stage, namely: (1) A-/TN-, (2) A+/TN-, (3) A+/TN+ and (4) A-/TN+.

Within the CDR = 0 group (i.e. cognitively normal individuals), a one-way ANCOVA showed a significant difference between the four biomarker profiles after adjusting for the effect of age (F3,286 = 21.3, P < 0.0001, ηp2 = 0.183). A Bonferroni post hoc test revealed that the A+/TN- profile had significant lower CSF sTREM2 compared to either other biomarker profile (Fig. 2). Only the A-/TN+ profile had significant higher CSF sTREM2 compared to the normal biomarkers profile (i.e. A-/TN-).

CSF sTREM2 in the A/T/N framework. Scatter plot depicting the levels of CSF sTREM2 for each of the four biomarker profiles, as defined by the A/T/N framework, coupled with clinical staging, as defined by CDR. The biomarkers groups T (tau pathology) and N (neurodegeneration) were merged in order to reduce the number of groups to compare. The CDR = 1 stage includes some biomarker profiles will low number of subjects, which precludes performing statistical analysis. They are still shown in the figure for sake of completeness. Each biomarker category is represented in a different colour: healthy controls are depicted in blue, Alzheimer’s continuum category in red, SNAP category in green, and purple depicts biomarker profiles not assigned in a specific category in the present study. The analysis reported in the main text was conducted excluding the TREM2 rare variants carriers, the P-values are reported in bold, and the number of individuals (n) per group indicated. Including these carriers (depicted in yellow) rendered similar results (P-values reported between brackets). Solid bars represent the mean and the standard deviation (SD). P-values were assessed by a one-way ANCOVA adjusted for age, followed by Bonferroni corrected post hoc pairwise comparisons. Abbreviations: A: Aβ pathology biomarker status; AD: Alzheimer’s disease; CDR: clinical dementia rating; CSF: cerebrospinal fluid; N: neurodegeneration biomarker status; SNAP: suspected non-Alzheimer’s pathology; T: tau pathology biomarker status.

Within the CDR = 0.5 group (i.e. very mild dementia), there was also a significant difference between the four biomarker profiles (F3,582 = 40.7, P < 0.0001, ηp2 = 0.173) and the A+/TN- profile had also the significantly lowest CSF sTREM2 compared to either other biomarker profile (Fig 2). Both the A+/TN+ and the A-/TN+ biomarker profiles had significant higher CSF sTREM2 compared to the A-/TN- profile (Fig. 2). The CDR = 1 group did not yield a sufficient number of subjects per A/T/N profile to allow for a group comparison.

We repeated the former analysis also including the individuals with TREM2 rare variants (n = 43; demographics in Table S1, see Additional file 1) and this did not change our conclusions derived from the main analysis (Fig. 2).

We also repeated the same analysis classifying the participants based only on their Aβ pathology (A; CSF Aβ1-42) and tau pathology status (T; CSF P-tau181P), that is A/T classification, or based only on their Aβ pathology (A; CSF Aβ1-42) and neurodegeneration status (N; CSF T-tau), that is A/N classification. The results are shown in Figure S2 (see Additional file 1) and they are similar to those shown with the A/TN classification of the main text. Thus, we conclude that the pathological processes that are downstream of Aβ pathology, both tau pathology and neurodegeneration, are associated with increased CSF sTREM2.

CSF sTREM2 changes across the Alzheimer’s continuum

Next we asked if CSF sTREM2 changes during the course of the disease as previously described in our study on late onset-AD [25]. We modeled the evolution of AD comparing the biomarker-defined groups (Table 1) that reflect the temporary course of late-onset AD, similar to what was proposed by the previous 2011 NIA-AA diagnostic criteria [32,33,34]. Thus, we compared the ‘healthy controls’ group (highlighted in blue in Table 1 and corresponding to the the ‘CDR = 0 A-/TN-’ group), with those belonging to the Alzheimer’s continuum (highlighted in red in Table 1), which included: ‘Preclinical AD A+/TN-’, ‘Preclinical AD A+/TN+’, ‘AD CDR = 0.5’ and ‘AD CDR = 1’. A one-way ANCOVA revealed that CSF sTREM2 was significantly different between groups after adjusting for the effect of age (F4,575 = 11.5, P < 0.0001, ηp2 = 0.074). A post hoc analysis using the Bonferroni criterion for significance indicated that the average CSF sTREM2 was significantly higher in the ‘AD CDR = 0.5’ group than in the ‘healthy controls’ and ‘Preclinical AD A+TN-’ groups (P = 0.034 and P < 0.0001, respectively; Fig. 3). Similar results were obtained when the individuals carrying a TREM2 rare variant were included (Fig. 3). Thus, these results replicate our and other groups previous findings of increased CSF sTREM2 in early symptomatic stages of late-onset AD in an independent sample [23,24,25, 29].

CSF sTREM2 across the Alzheimer’s continuum. Scatter plot showing the levels of CSF sTREM2 in healthy controls (depicted in blue) and the different stages of the Alzheimer’s continuum (depicted in red). The main analysis was conducted excluding the TREM2 rare variants carriers, the P-values are reported in bold, and the number of individuals (n) per group indicated. Including these carriers (depicted in yellow) rendered similar results (P-values reported between brackets) P-values were assessed by a one-way ANCOVA adjusted for age, followed by Bonferroni corrected post hoc pairwise comparisons. Abbreviations: A: Aβ pathology biomarker status; AD: Alzheimer’s disease; CDR: clinical dementia rating; CSF: cerebrospinal fluid; N: neurodegeneration biomarker status; SNAP: suspected non-Alzheimer’s pathophysiology; T: tau pathology biomarker status.

CSF sTREM2 is associated with T-tau and P-tau but not Aβ1-42

Finally, we studied the associations of CSF sTREM2 with each of the CSF core biomarkers of AD, that is T-tau, P-tau181P and Aβ1-42, in linear regression models adjusted for age. The associations were tested separately in three groups based on their biomarker profile (see Table 1): (1) healthy controls, (2) individuals of the Alzheimer’s continuum and (3) in the SNAP groups. Consistent with previous findings, CSF sTREM2 is associated with T-tau and P-tau181P in the three groups studied (Fig. 4). In contrast, no significant associations were found between CSF sTREM2 and Aβ1-42 (Fig. 4). Including the CSF biomarkers outliers (see Additional file 1: Table S2), or including the individuals carrying a TREM2 rare variants (see Additional file 1: Table S3), did not change our findings.

Association of CSF sTREM2 and AD core CSF biomarkers. Scatter plots representing the associations of CSF sTREM2 with each of the AD CSF core biomarkers: T-tau (a), P-tau181P (b), and Aβ1-42 (c) in three different groups defined by the biomarker profile: healthy controls (blue), Alzheimer’s continuum (red) and SNAP groups (green). The solid lines indicate the regression line and the 95% confidence interval for each of the groups. The standardized regression coefficients (β) and the P-values are shown and were computed using a linear model adjusting for age, and are conducted excluding the outliers values. Including them, did not change the conclusions (see Additional file 1: Table S2). We also performed the analysis including the participants carrying a TREM2 rare variant (depicted in yellow) and the results were similar (see Additional file 1: Table S3). Abbreviations: Aβ1-42: amyloid-beta 42; T-tau: total tau; P-tau: tau phosphorylated at Threonine 181; SNAP: suspected non-Alzheimer’s pathology.

Discussion

In the present study, we assessed the microglial-activity marker CSF sTREM2 within the early phases of AD. To this end, we applied the biomarker-based A/T/N classification in combination with clinical staging [27]. The use of this classification system enabled us to unravel the effect of Aβ pathology and its downstream processes (i.e. tau pathology and neurodegeneration) on the levels of CSF sTREM2. Interestingly, they are differentially associated with CSF sTREM2. While pure Aβ deposition (as defined here as low CSF Aβ1-42) is associated with decreased CSF sTREM2, tau pathology or neurodegeneration (as defined here as increased CSF P-tau181P or CSF T-tau, respectively) are associated with an increase in CSF sTREM2. The higher CSF sTREM2 in the SNAP groups confirm that CSF sTREM2 rises with neurodegeneration without Aβ pathology.

Moreover, we show that the levels of CSF sTREM2 differ between TREM2 variants and they are increased in the p.R47H TREM2 variant compared to non-carriers, but decreased in the p.L211P variant and remained unchanged in the p.R62H variant, which is consistent with previous reports [24]. Increased levels of sTREM2 in the p.R47H variant were somewhat surprising; however, very little is known if that variant affects proteolytic processing of TREM2. In contrast, the increased levels of the p.H157Y variant is in line with our previous findings in cultured cells demonstrating that this variant increased shedding of TREM2 and therefore decreased TREM2 dependent phagocytosis [17]. A word of caution should be noted with the p.D87N variant, because the lower levels could be due, at least partially, to the lesser affinity of the antibody to this variant.

Among the strengths of this study are the large and well-characterized sample size and the use of a reliable assay to measure sTREM2. Yet, this study has some limitations. First, this is a cross-sectional study and the results need to be confirmed in a longitudinal setting. Second, we used the CSF biomarkers to classify the ADNI participants in the A/T/N classification. Although the role of CSF biomarkers in AD is well-established and a complete A/T/N characterization is possible only with CSF biomarkers, CSF T-tau may not necessarily reflect neurodegeneration but could result from physiological production of tau [46]. Here, we found CSF P-tau181P and CSF T-tau to be highly correlated (only 5.4% of all the ADNI participants had a discrepant T and N biomarker group), and consequently we merged the “T” (tau pathology) and “N” (neurodegeneration) groups. Importantly, the TN- group had normal levels of both T-tau and P-tau181P, which reasonably ensure that other comorbidities that may cause neural injury (and hence microglial activation) are excluded. A plethora of other biofluid and neuroimaging markers (i.e. Aβ and tau PET, blood and CSF neurofilament light protein, anatomic MRI and FDG-PET) are in principle applicable for the implementation of the A/T/N classification, and future studies using these biomarkers are needed to confirm our results.

The A/T/N classification used herein is a descriptive biomarker-based classification that does not assume any temporal sequence of events in AD and is independent of the clinical stage of the disease. By applying this classification framework, we found an unexpected observation, namely a decrease of CSF sTREM2 in individuals with evidence of Aβ pathology but without signs of tau pathology or neurodegeneration. We did not observe this finding in previous studies, probably due to the low number of participants in the preclinical stage of late-onset AD and because we did not apply the A/T/N classification [25]. Noteworthy, we previously observed in ADAD that CSF sTREM2 was lower in ADAD mutation carriers than in non-carriers at very early stages (EYO < -15; CSF T-tau becomes significantly increased in mutation carriers at EYO = -15), yet statistically non-significant [26]. In contrast, we show here that CSF sTREM2 increases as soon there are signs of we show here that CSF sTREM2 increases, both in the context of AD (that is with co-occurrence of Aβ pathology) or in the SNAP patients (where there is no Aβ underlying pathology). Consistent with these findings, CSF sTREM2 is distinctly associated with CSF T-tau and CSF P-tau181P, but not with CSF Aβ1-42. A word of caution is needed in the SNAP category, given that this is an heterogenous group that most likely exhibits a non-AD related neurodegeneration. Well-powered future studies should address how CSF sTREM2 changes in neurodegenerative diseases different from AD.

The flexibility of this new classification framework also enabled us to model the natural history of AD and confirm in the ADNI study our previous findings in participants of several European memory clinics [25] who were classified using the 2011 NIA-AA criteria [32,33,34, 36]. Herein, we demonstrate that, after the initial decrease of CSF sTREM2 in the ‘Preclinical AD A+/TN-’ group, CSF sTREM2 rise is the ‘Preclinical AD A+/TN+’group and in the early symptomatic stage (CDR = 0.5) of AD, albeit only statistically significant in the latter group. These findings therefore replicate our [25, 26] and other groups [23, 24, 29] previous findings in which an increase in CSF sTREM2 in early symptomatic AD was observed.

The mechanism underlying the dynamic changes of CSF sTREM2 throughout the course of the disease still need to be investigated. Several studies have consistently demonstrated that microglia upregulate TREM2 expression in AD mouse models and in human AD brains [3, 47, 48]. Moreover, detailed transcriptomics studies that investigated microglia in mouse models of AD and neurodegeneration showed that TREM2 is upregulated in the disease-associated microglia (DAM) [1, 49,50,51,52,53]. This is consistent with the finding of increased CSF sTREM2 in stages downstream of Aβ accumulation, that is when tau pathology and/or neurodegeneration occur and microglia may adopt their disease associated molecular signature. We were surprised, however, by the observation of an initial CSF sTREM2 decrease in the only Aβ-pathology stage, which corresponds to the earliest stage of the disease. The possible mechanisms behind this observation are still elusive. However, it has been described that microglia are activated in two steps with an initial TREM2-independent process followed by a TREM2-dependent process [49]. The CSF sTREM2 increase observed following the initially low levels may reflect the second step of activation. An alternative explanation would be that microglia initially forms a barrier around plaques [54, 55] and the sTREM2 released by microglia is retained within the plaque, until the barrier fails, and subsequent neural injury starts. Finally, it could also be argued that subjects with low TREM2-function (and hence lower CSF sTREM2 levels) are more prone to experience an accelerated early amyloidogenesis (Parhizkar et al. Nat. Neursci in press) and are therefore overrepresented in the Preclinical AD A+TN- group. Nevertheless, we are cognizant of the fact that this is an observational study and the findings reported herein do not elucidate precise mechanisms. Further work with longitudinal data is needed to address whether the stage-dependent changes in CSF sTREM2 predict a better or worse clinical outcome.

In conclusion, the present study represents the first attempt to study CSF sTREM2 based on the A/T/N classification framework. We demonstrate in the ADNI cohort that the increase in CSF sTREM2 which occurs in early stages parallels the increase in biomarkers of tau pathology and neurodegeneration. In contrast, Aβ deposition in the absence of tau deposition and neurodegeneration is associated with lower CSF sTREM2.

Abbreviations

- Aβ:

-

Amyloid β-peptide

- AD:

-

Alzheimer’s disease;

- ADAD:

-

Autosomal-dominant Alzheimer’s disease

- CDR:

-

Clinical dementia rating score

- CNS:

-

Central nervous system

- CSF:

-

Cerebrospinal fluid

- EYO:

-

Estimated years from symptom onset

- SNAP:

-

Suspected non-Alzheimer’s pathology

- sTREM2:

-

Soluble triggering receptor expressed on myeloid cells 2

- TREM2:

-

Triggering receptor expressed on myeloid cells 2

References

Hickman SE, Kingery ND, Ohsumi TK, Borowsky ML, Wang LC, Means TK, et al. The microglial sensome revealed by direct RNA sequencing. Nat Neurosci. 2013;16:1896–905.

Kleinberger G, Yamanishi Y, Suárez-Calvet M, Czirr E, Lohmann E, Cuyvers E, et al. TREM2 mutations implicated in neurodegeneration impair cell surface transport and phagocytosis. Sci Transl Med. 2014;6:243ra86.

Wang Y, Cella M, Mallinson K, Ulrich JD, Young KL, Robinette ML, et al. TREM2 lipid sensing sustains the microglial response in an Alzheimer’s disease model. Cell. 2015;160:1061–71.

Colonna M, Wang Y. TREM2 variants: new keys to decipher Alzheimer disease pathogenesis. Nat Rev Neurosci. 2016;17:201–7.

Mazaheri F, Snaidero N, Kleinberger G, Madore C, Daria A, Werner G, et al. TREM2 deficiency impairs chemotaxis and microglial responses to neuronal injury. EMBO Rep. 2017;18:1186–98.

Xiang X, Werner G, Bohrmann B, Liesz A, Mazaheri F, Capell A, et al. TREM2 deficiency reduces the efficacy of immunotherapeutic amyloid clearance. EMBO Mol Med. 2016;8:992–1004.

Guerreiro R, Wojtas A, Bras J, Carrasquillo M, Rogaeva E, Majounie E, et al. TREM2 variants in Alzheimer’s disease. N Engl J Med. 2013;368:117–27.

Jonsson T, Stefansson H, Steinberg S, Jonsdottir I, Jonsson PV, Snaedal J, et al. Variant of TREM2 Associated with the Risk of Alzheimer’s Disease. N Engl J Med. 2013;368:107–16.

Borroni B, Ferrari F, Galimberti D, Nacmias B, Barone C, Bagnoli S, et al. Heterozygous TREM2 mutations in frontotemporal dementia. Neurobiol Aging. 2014;35:934.e7–10

Cady J, Koval ED, Benitez BA, Zaidman C, Jockel-Balsarotti J, Allred P, et al. TREM2 variant p.R47H as a risk factor for sporadic amyotrophic lateral sclerosis. JAMA Neurol. 2014;71:449–53.

Cuyvers E, Bettens K, Philtjens S, Van Langenhove T, Gijselinck I, van der Zee J, et al. Investigating the role of rare heterozygous TREM2 variants in Alzheimer’s disease and frontotemporal dementia. Neurobiol Aging. 2014;35:726.e11–9.

Rayaprolu S, Mullen B, Baker M, Lynch T, Finger E, Seeley WW, et al. TREM2 in neurodegeneration: evidence for association of the p.R47H variant with frontotemporal dementia and Parkinson’s disease. Mol Neurodegener. 2013;8:19.

Guerreiro R, Bilgic B, Guven G, Brás J, Rohrer J, Lohmann E, et al. A novel compound heterozygous mutation in TREM2 found in a Turkish frontotemporal dementia-like family. Neurobiol Aging. 2013;34:2890.e1–5.

Paloneva J, Manninen T, Christman G, Hovanes K, Mandelin J, Adolfsson R, et al. Mutations in two genes encoding different subunits of a receptor signaling complex result in an identical disease phenotype. Am J Hum Genet. 2002;71:656–62.

Wunderlich P, Glebov K, Kemmerling N, Tien NT, Neumann H, Walter J. Sequential Proteolytic Processing of the Triggering Receptor Expressed on Myeloid Cells-2 (TREM2) Protein by Ectodomain Shedding and γ-Secretase-dependent Intramembranous Cleavage. J Biol Chem. 2013;288:33027–36.

Piccio L, Buonsanti C, Cella M, Tassi I, Schmidt RE, Fenoglio C, et al. Identification of soluble TREM-2 in the cerebrospinal fluid and its association with multiple sclerosis and CNS inflammation. Brain. 2008;131:3081–91.

Schlepckow K, Kleinberger G, Fukumori A, Feederle R, Lichtenthaler SF, Steiner H, et al. An Alzheimer-associated TREM2 variant occurs at the ADAM cleavage site and affects shedding and phagocytic function. EMBO Mol Med. 2017;9:1356–65.

Feuerbach D, Schindler P, Barske C, Joller S, Beng-Louka E, Worringer KA, et al. ADAM17 is the main sheddase for the generation of human triggering receptor expressed in myeloid cells (hTREM2) ectodomain and cleaves TREM2 after Histidine 157. Neurosci Lett. 2017;660:109–14.

Thornton P, Sevalle J, Deery MJ, Fraser G, Zhou Y, Ståhl S, et al. TREM2 shedding by cleavage at the H157-S158 bond is accelerated for the Alzheimer’s disease-associated H157Y variant. EMBO Mol Med. 2017;9:1366–78.

Kleinberger G, Brendel M, Mracsko E, Wefers B, Groeneweg L, Xiang X, et al. The FTD-like syndrome causing TREM2 T66M mutation impairs microglia function, brain perfusion, and glucose metabolism. EMBO J. 2017;36:1837–53.

Henjum K, Almdahl IS, Årskog V, Minthon L, Hansson O, Fladby T, et al. Cerebrospinal fluid soluble TREM2 in aging and Alzheimer’s disease. Alzheimers Res Ther. 2016;8:17.

Brendel M, Kleinberger G, Probst F, Jaworska A, Overhoff F, Blume T, et al. Increase of TREM2 during Aging of an Alzheimer’s Disease Mouse Model Is Paralleled by Microglial Activation and Amyloidosis. Front Aging Neurosci. 2017;9:8.

Heslegrave A, Heywood W, Paterson R, Magdalinou N, Svensson J, Johansson P, et al. Increased cerebrospinal fluid soluble TREM2 concentration in Alzheimer’s disease. Mol Neurodegener. 2016;11:3.

Piccio L, Deming Y, Del-Águila JL, Ghezzi L, Holtzman DM, Fagan AM, et al. Cerebrospinal fluid soluble TREM2 is higher in Alzheimer disease and associated with mutation status. Acta Neuropathol. 2016;131:925–33.

Suárez-Calvet M, Kleinberger G, Araque Caballero MÁ, Brendel M, Rominger A, Alcolea D, et al. sTREM2 cerebrospinal fluid levels are a potential biomarker for microglia activity in early-stage Alzheimer’s disease and associate with neuronal injury markers. EMBO Mol Med. 2016;8:466–76.

Suárez-Calvet M, Araque Caballero MÁ, Kleinberger G, Bateman RJ, Fagan AM, Morris JC, et al. Early changes in CSF sTREM2 in dominantly inherited Alzheimer’s disease occur after amyloid deposition and neuronal injury. Sci Transl Med. 2016;8:369ra178.

Jack CR, Bennett DA, Blennow K, Carrillo MC, Feldman HH, Frisoni GB, et al. A/T/N: An unbiased descriptive classification scheme for Alzheimer disease biomarkers. Neurology. 2016;87:539–47.

Jack CR, Bennett DA, Blennow K, Carrillo MC, Dunn B, Haeberlein SB, et al. NIA-AA Research Framework: Toward a biological definition of Alzheimer’s disease. Alzheimer’s Dement. 2018;14:535–62.

Liu D, Cao B, Zhao Y, Huang H, McIntyre RS, Rosenblat JD, et al. Soluble TREM2 changes during the clinical course of Alzheimer’s disease: A meta-analysis. Neurosci Lett. 2018;686:10–6.

Weiner MW, Veitch DP, Aisen PS, Beckett LA, Cairns NJ, Green RC, et al. Recent publications from the Alzheimer’s Disease Neuroimaging Initiative: Reviewing progress toward improved AD clinical trials. Alzheimer’s Dement. 2017;13:e1–85.

Morris JC. The Clinical Dementia Rating (CDR): current version and scoring rules. Neurology. 1993;43:2412–4.

Sperling RA, Aisen PS, Beckett LA, Bennett DA, Craft S, Fagan AM, et al. Toward defining the preclinical stages of Alzheimer’s disease: recommendations from the National Institute on Aging-Alzheimer’s Association workgroups on diagnostic guidelines for Alzheimer’s disease. Alzheimers Dement. 2011;7:280–92.

Albert MS, DeKosky ST, Dickson D, Dubois B, Feldman HH, Fox NC, et al. The diagnosis of mild cognitive impairment due to Alzheimer’s disease: recommendations from the National Institute on Aging-Alzheimer’s Association workgroups on diagnostic guidelines for Alzheimer’s disease. Alzheimers Dement. 2011;7:270–9.

McKhann GM, Knopman DS, Chertkow H, Hyman BT, Jack CR, Kawas CH, et al. The diagnosis of dementia due to Alzheimer’s disease: recommendations from the National Institute on Aging-Alzheimer’s Association workgroups on diagnostic guidelines for Alzheimer’s disease. Alzheimers Dement. 2011;7:263–9.

Caroli A, Prestia A, Galluzzi S, Ferrari C, van der Flier WM, Ossenkoppele R, et al. Mild cognitive impairment with suspected nonamyloid pathology (SNAP): Prediction of progression. Neurology. 2015;84:508–15.

Jack CR, Knopman DS, Weigand SD, Wiste HJ, Vemuri P, Lowe V, et al. An operational approach to National Institute on Aging-Alzheimer’s Association criteria for preclinical Alzheimer disease. Ann Neurol. 2012;71:765–75.

Dani M, Brooks DJ, Edison P. Suspected non-Alzheimer’s pathology – Is it non-Alzheimer’s or non-amyloid? Ageing Res Rev. 2017;36:20–31.

Jack CR, Knopman DS, Chételat G, Dickson D, Fagan AM, Frisoni GB, et al. Suspected non-Alzheimer disease pathophysiology — concept and controversy. Nat Rev Neurol. 2016;12:117–24.

Hansson O, Seibyl J, Stomrud E, Zetterberg H, Trojanowski JQ, Bittner T, et al. CSF biomarkers of Alzheimer’s disease concord with amyloid-β PET and predict clinical progression: A study of fully automated immunoassays in BioFINDER and ADNI cohorts. Alzheimer’s Dement. 2018;14:1470–81.

Bittner T, Zetterberg H, Teunissen CE, Ostlund RE, Militello M, Andreasson U, et al. Technical performance of a novel, fully automated electrochemiluminescence immunoassay for the quantitation of β-amyloid (1–42) in human cerebrospinal fluid. Alzheimer’s Dement. 2016;12:517–26.

Jay TR, von Saucken VE, Landreth GE. TREM2 in Neurodegenerative Diseases. Mol Neurodegener. 2017;12:56.

Jin SC, Carrasquillo MM, Benitez BA, Skorupa T, Carrell D, Patel D, et al. TREM2 is associated with increased risk for Alzheimer’s disease in African Americans. Mol Neurodegener. 2015;10:19.

Thelen M, Razquin C, Hernández I, Gorostidi A, Sánchez-Valle R, Ortega-Cubero S, et al. Investigation of the role of rare TREM2 variants in frontotemporal dementia subtypes. Neurobiol Aging. 2014;35:2657.e13–19.

Roussos P, Katsel P, Fam P, Tan W, Purohit DP, Haroutunian V. The triggering receptor expressed on myeloid cells 2 (TREM2) is associated with enhanced inflammation, neuropathological lesions and increased risk for Alzheimer’s dementia. Alzheimer’s Dement. 2015;11:1163–70.

Lu Y, Liu W, Wang X. TREM2 variants and risk of Alzheimer’s disease: a meta-analysis. Neurol Sci. 2015;36:1881–8.

Sato C, Barthélemy NR, Mawuenyega KG, Patterson BW, Gordon BA, Jockel-Balsarotti J, et al. Tau Kinetics in Neurons and the Human Central Nervous System. Neuron. 2018;97:1284–98 e7.

Frank S, Burbach GJ, Bonin M, Walter M, Streit W, Bechmann I, et al. TREM2 is upregulated in amyloid plaque-associated microglia in aged APP23 transgenic mice. Glia. 2008;56:1438–47.

Lue LF, Schmitz CT, Serrano G, Sue LI, Beach TG, Walker DG. TREM2 Protein Expression Changes Correlate with Alzheimer’s Disease Neurodegenerative Pathologies in Post-Mortem Temporal Cortices. Brain Pathol. 2015;25:469–80.

Keren-Shaul H, Spinrad A, Weiner A, Matcovitch-Natan O, Dvir-Szternfeld R, Ulland TK, et al. A Unique Microglia Type Associated with Restricting Development of Alzheimer’s Disease. Cell. 2017;169:1276–90 e17.

Krasemann S, Madore C, Cialic R, Baufeld C, Calcagno N, El Fatimy R, et al. The TREM2-APOE Pathway Drives the Transcriptional Phenotype of Dysfunctional Microglia in Neurodegenerative Diseases. Immunity. 2017;47:566–81 e9.

Holtman IR, Raj DD, Miller JA, Schaafsma W, Yin Z, Brouwer N, et al. Induction of a common microglia gene expression signature by aging and neurodegenerative conditions: a co-expression meta-analysis. Acta Neuropathol Commun. 2015;3:31.

Chiu IM, Morimoto ETA, Goodarzi H, Liao JT, O’Keeffe S, Phatnani HP, et al. A neurodegeneration-specific gene-expression signature of acutely isolated microglia from an amyotrophic lateral sclerosis mouse model. Cell Rep. 2013;4:385–401.

Orre M, Kamphuis W, Osborn LM, Jansen AHP, Kooijman L, Bossers K, et al. Isolation of glia from Alzheimer’s mice reveals inflammation and dysfunction. Neurobiol Aging. 2014;35:2746–60.

Condello C, Yuan P, Schain A, Grutzendler J. Microglia constitute a barrier that prevents neurotoxic protofibrillar Aβ42 hotspots around plaques. Nat Commun. 2015;6:6176.

Wang Y, Ulland TK, Ulrich JD, Song W, Tzaferis JA, Hole JT, et al. TREM2-mediated early microglial response limits diffusion and toxicity of amyloid plaques. J Exp Med. 2016;213:667–75.

Jiang T, Tan L, Chen Q, Tan MS, Zhou JS, Zhu XC, et al. A rare coding variant in TREM2 increases risk for Alzheimer’s disease in Han Chinese. Neurobiol Aging. 2016;42:217.e1–3.

Acknowledgements

We would like to thank all the researchers and participants in the ADNI initiative. We also thank Nicole Exner for technical assistance and Nicholas Ashton for critically reading the manuscript and helpful discussion.

Data used in preparation of this article were obtained from the Alzheimer’s Disease Neuroimaging Initiative (ADNI) database (adni.loni.usc.edu). As such, the investigators within the ADNI contributed to the design and implementation of ADNI and/or provided data but did not participate in analysis or writing of this report. A complete listing of ADNI investigators can be found at: http://adni.loni.usc.edu/wp-content/uploads/how_to_apply/ADNI_Acknowledgement_List.pdf

Availability data and materials

The dataset supporting the conclusions of this article is available in the ADNI site, http://adni.loni.usc.edu/.

Funding

This work was supported by the Deutsche Forschungsgemeinschaft (DFG) within the framework of the Munich Cluster for Systems Neurology (EXC 1010 SyNergy), a DFG funded Koselleck Project (HA1737/16-1 to CH) and the AFTD Biomarker Award (to MSC, JL, ME and CH). MSC received funding from the European Union’s Horizon 2020 Research and Innovation Program under the Marie Sklodowska-Curie action grant agreement No 752310. This work was also supported by grants from the National Institutes of Health (R01AG044546, RF1AG053303, RF1AG058501, and U01AG058922), YD was supported by a NIMH institutional training grant (T32MH014877). LP was supported by a grant from the Fondazione Italiana Sclerosi Multipla (FISM 2017/R/20). EM was supported by a grant from the Ad-Hoc Committee for Young Neurologist (Spanish Society of Neurology) and Health Institute Carlos III (funding program for the mobility of the researchers).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Consortia

Contributions

MSC, EMR, GK, AC, KF, BN, EE, YD and LP performed the experiments. MSC, MAC, NF, YD, ME and CH analyzed and interpreted the data. KS and EMR performed the cell culture experiments. YD, LP, CMK and CC were involved in extracting the genetic data. JL, LS, JQT, MW contributed with patient samples and/or data. MSC, ME and CH designed the study and wrote the manuscript. All authors critically reviewed and approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

The study was approved by the Ludwig-Maximilians Universität München institutional review board (IRB), as well as the IRB of all participating centers in ADNI.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

CH collaborates with DENALI Therapeutics and received speakers honoraria from Novartis and Roche. KS collaborates with DENALI. JL reports to receive consulting fees from Aesku, Axon Neuroscience and Ionis Pharmaceuticals, speakers’ fees from Bayer Vital and the Willi Gross and non-financial support from Abbvie, outside the submitted work. CC receives research support from Biogen, EISAI, Alector and Parabon, and is a member of the advisory board of ADx Healthcare. The funders of the study had no role in the collection, analysis, or interpretation of data; in the writing of the report; or in the decision to submit the paper for publication. The remaining authors declare that they have no competing of interest.

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Additional file

Additional file 1:

CSF sTREM2 measurement. Figure S1. Effects of rare TREM2 variants on antibody affinities. Figure S2. CSF sTREM2 in the A/T and in the A/N classifications. Table S1. Demographic and clinical characteristics of the entire sample. Table S2. Associations of CSF sTREM2 with AD CSF core biomarkers including the biomarkers outliers. Table S3. Associations of CSF sTREM2 with AD CSF core biomarkers including subjects carrying a TREM2 rare variant. (DOCX 1992 kb)

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made. The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver (http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/) applies to the data made available in this article, unless otherwise stated.

About this article

Cite this article

Suárez-Calvet, M., Morenas-Rodríguez, E., Kleinberger, G. et al. Early increase of CSF sTREM2 in Alzheimer’s disease is associated with tau related-neurodegeneration but not with amyloid-β pathology. Mol Neurodegeneration 14, 1 (2019). https://doi.org/10.1186/s13024-018-0301-5

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s13024-018-0301-5