Abstract

Background

Rare disease patient-reported outcome measures (PROMs) require linguistic adaptation to overcome the challenge of geographically dispersed patient populations. Importantly, PROMs such as health-related quality of life (HRQoL) should accurately capture responses to patient-identified concerns. The Systemic Sclerosis Quality of Life Questionnaire (SScQoL) is a 29-item tool validated in six languages. Previous evaluation of the German version revealed problems with dichotomous responses. This study aimed to revise the German SScQoL, extend the response structure, and evaluate content and construct validity, reliability and unidimensionality.

Methods

The instrument validation study involved revising the German SScQoL response structure, cognitive debriefing with patients and validation using Rasch analysis. The revised SScQoL was completed by Swiss-German-speaking patients with SSc within the Swiss MANagement Of Systemic Sclerosis (MANOSS) study. Rasch analysis was employed to test the validity, reliability and unidimensionality of the revised instrument.

Results

Based on cognitive debriefing with patients (n = 6) dichotomous items were extended to a polytomous 4-point response structure. A total of 78 patients completed the revised SScQoL. Initial analysis of the 29 items suggested the scale lacked fit to the model (χ2 = 51.224, df = 29, p = 0.007). Grouping items into five domains resulted in an adequate fit to the Rasch model (χ2 = 5.343, df = 5, p = 0.376) and unidimensionality (proportion of significant independent t tests: 0.045, 95% CI 0.016–0.114). Overall, the scale was well targeted, had high internal consistency (Person Separation Index, PSI = 0.931) and worked consistently in patients with different demographic and clinical characteristics.

Conclusions

The revised German SScQoL has a 4-point response structure and is a valid, reliable measure. Rasch analysis is useful for validating continuous response structure of quality of life measures. Further evaluation of measurement equivalence with other German-speaking cultures is required for multinational comparisons and data pooling.

Similar content being viewed by others

Background

For many rare diseases, the natural history of the condition is poorly understood especially as it relates to the impact on health-related quality of life (HRQoL). Importantly, patients affected by rare diseases are geographically dispersed. Therefore, validated patient-reported outcome measures (PROMs) including HRQoL are needed in multiple languages. Systemic sclerosis (SSc) is a rare multisystemic, connective tissue disease associated with significant morbidity, physical and psychosocial impact [1]. Pathogenesis is dominated by vascular problems such as vasospasm of digital arteries (Raynaud's phenomenon); inflammation and activation of (auto)immune response; and fibrosis of the skin and visceral organs causing irreversible scarring and organ failure. The disease is heterogeneous in clinical manifestations (e.g. autoantibody profile, disease progression, skin involvement) and patients are typically grouped into two disease subsets: limited cutaneous systemic sclerosis (lcSSc) and diffuse cutaneous systemic sclerosis (dcSSc).

Importantly, SSc is a long-term condition and both disease subsets exhibit multiple symptoms including fatigue, hand stiffness, digital ulcers, shortness of breath, pain, and mouth-, dental- and gastrointestinal-problems [2, 3]. Psychosocial problems such as work disability, depression, fear of disease progression, and body image dissatisfaction are often evident [4, 5]. Accordingly, patients’ quality of life is often severely affected [6, 7]. Notably, the diffuse form (dcSSc) is associated with greater negative impact on quality of life compared to limited SSc (lcSSc) without organ damage [6].

To systematically address the range of SSc effects, it is important to assess disease-specific aspects of HRQoL using an outcome measure with demonstrated reliability and validity for some specific languages. HRQoL measures are fundamental in developing PROMs for chronic conditions to evaluate targeted interventions, increase well-being (e.g., detect need for supportive care), and reduce costs (e.g., earlier detection of relapses) [8,9,10]. Indeed, to achieve adequate sample sizes, rare disease research relies on registries (e.g. EUSTAR and EUSHNet) and demands international/multicenter collaboration given the limited number of affected individuals [11].

While the Health Assessment Questionnaire (HAQ) is a valid measure of physical disability, and commonly used for evaluating patients, it does not adequately take into account the psychosocial aspects or other disease-specific impact in people with SSc [12]. The Systemic Sclerosis Quality of Life Questionnaire (SScQoL) is the first PROM assessing disease-specific HRQoL in people with SSc [13, 14]. Reay et al. developed the instrument through a multi-phased process comprising qualitative interviews (one-to-one interview and focus groups) with people with SSc; development of the descriptive framework of SSc QoL; development of draft items derived from patients statements (90 items); Rasch analysis and item reduction (researchers with patient input—29 items); test–retest with hypothesis testing and structural equation modelling [14]. The developed SScQoL has 29 items with dichotomous (true/not true) responses, scored as ‘True’ = 1 or ‘Not true’ = 0, total score ranges between 0 and 29 with higher scores indicating a greater impact of the disease and consequently, decreased HRQoL [13, 14]. The items have been grouped into five domains which map onto the International Classification of Functioning, Disability and Health (ICF) framework [13], with scores for each domain ranging as follows: function: 0–6; emotional: 0–13; sleep: 0–2; social: 0–6; and pain: 0–2.

The SScQoL underwent a cross-cultural adaptation according to a five-step procedure described by Beaton et al. and validation in six European countries [13, 15]. As part of the cross-cultural adaptation the translated versions of the SScQoL were first completed by a group of 30 patients in each of the six countries (Germany, France, Italy, Poland, Spain, Sweden, and UK) who commented on the translated version before different versions were sent for psychometric testing using Rasch analysis [13]. Findings of the adaptation suggested a seamless adaptation across all countries but Germany where patients documented problems with 10 items [13]. Specifically, problems were identified in relation to the dichotomous ‘true/not true’ response structure in those items. German patients indicated a desire for a broader response structure to more accurately capture the full range of responses. In the subsequent psychometric testing phase, those items in the German SScQoL revealed significant deviations from the Rasch model, confirming the problems highlighted by patients. This suggested the need for revision of the German SScQoL [13]. The need for revision was in the item wording/presentation, response structure and further psychometric testing of the German SScQoL. The aim of this present study was to review the German SScQoL, expand the response structure, and examine content validity, construct validity, unidimensionality, and reliability of the scale.

Methods

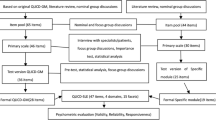

Design

This study consisted of two phases involving cognitive interviews for clarifying the cultural adaptation and a validation study to establish measurement validity of the adapted tool. In Phase 1, the SScQoL was refined in accordance with the International Society for Pharmacoeconomics and Outcomes Research (ISPOR) guideline [16, 17]. Phase 2, drew on data from the MANagement Of Systemic Sclerosis (MANOSS) cross-sectional study carried out in Switzerland [18, 19]. The MANOSS project aims to fill existing gaps in SSc care by developing an eHealth-enhanced rare disease chronic care model for SSc patients in Switzerland. Part of the MANOSS project involves conducting baseline data of SSc patients before implementing a new model of care (i.e., HRQoL). The MANOSS study was reviewed and approved by the responsible Swiss ethics committee in September 2018 (EKNZ 2018‐01206).

Measures

In phase 1, the original English SScQoL and German translation were compared independently by two researchers from Germany (KH) and Switzerland (AK) respectively. The revised translations of both researchers were discussed until consensus was achieved. Subsequently, an expert committee (MN, DN, KH, AK) expanded the response structure for items 1, 3–5, 7–14, 16–17, 19–22, and 25–29 from dichotomous (true/not true) into polytomous (‘always’, ‘usually’, ‘sometimes’, ‘never’) responses. The final version was back-translated into English language by a professional translator. In cognitive interviews, a convenience sample of patients with SSc completed the new version while ‘thinking aloud’ and commented on relevance of the items and the response structure. Briefly, participants were encouraged to read all SScQoL items while verbalizing their thoughts concurrently. Additionally, cognitive interviews were used for cognitive debriefing to identify problems interpreting items and response options in the intended way [20, 21]. This approach has shown to be appropriate for quality of life items and for detecting unanticipated problems in participant response behaviour with minimal interviewer-imposed bias [20, 22].

In phase 2, the validation study, German-speaking SSc patients of the MANOSS cross-sectional survey (March–August 2019) completed the revised (polytomous) SScQoL [18]. Participants completed either a paper format version and returned it by mail or completed the revised SScQoL in a web-based format. Participants provided sociodemographic data (sex, age, education, employment status), self-reported disease information (subset: lSSc, dSSc, Overlap syndrome1 or unknown), and disease duration.

Participants

For phase 1, a convenience sample of six SSc patients spanning a range of SSc disease severity/experiences and with varied educational levels was recruited from a Swiss University hospital (Inselspital, Bern, Switzerland), a German University hospital (Medizinische Hochschule Hannover, Germany) and a German outpatient rheumatology clinic (rheumapraxis an der hase, Osnabrück, Germany). They were included if they (1) had an SSc diagnosis assured by a physician, were (2) adult (> 18 years), and (3) understood the German language. They were asked to assess the face validity of the revised SScQoL. For phase 2, patients were recruited according to the MANOSS protocol [18]. Patients were recruited from four Swiss University hospitals, one regional (cantonal) hospital, rheumatology outpatient clinics, and the Swiss SSc patient association. Participants were included if they were (1) adult (> 18 years), (2) received care in the Swiss healthcare system, and (3) understood the German language.

Data analysis

Cognitive interview data were analysed by an expert committee (AK, MN, KH, AR, DN) who made final decisions on the revised German SScQoL. For phase 2, the Swiss sample is described using descriptive statistics including frequencies, percentages, median, interquartile range (IQR), mean and standard deviation (SD). To assess whether the German SScQoL had retained its validity and reliability following the revision process, we used Rasch analysis—a psychometric testing technique that compares collected data with the Rasch model [19, 23]. Originally used in education, Rasch analysis has gained wide acceptance in the health sciences [19]. Fit to the Rasch model implies construct validity, reliability and statistical sufficiency of the item scores [23]. Rasch analysis was performed using RUMM2030 software (Perth, WA: RUMM Laboratory Pty Ltd) with the Master’s Partial Credit Model (PCM), a polytomous generalization of the Rasch model, which does not impose a common threshold structure across all items [19].

First, each of the 29 SScQoL items was assessed for ‘fit’ to the Rasch model to examine how the 29-item tool works as a scale. Second, items were grouped into the 5-domains established in the previous cross-cultural validation study (Ndosi et al.) and tested as a 5-subscale measure of quality of life in SSc. Detailed descriptions of the Rasch model requirements are published elsewhere [19]. Briefly, model fit was tested by Chi-square-based fit statistics comparing differences between observed values and those expected by the model, i.e., (i) item-person interaction statistics, expressed as a Z score are expected to have a mean of zero (range − 2.5 to 2.5) and standard deviation (SD) of one and (ii) a non-significant Chi-square probability. In addition to fit statistics, internal consistency (inter-relatedness of items) demonstrating scale reliability was assessed using Person Separation Index (PSI) which functions in the same way as Cronbach’s alpha but is expressed in a logit scale. A minimal PSI value of 0.7 is accepted for assessment at a group level and 0.85 for individual level [19]. Another type of reliability, the invariance of the tool (also known as differential item functioning—DIF) was established by testing if there was a response bias by different subgroups of patients based on personal and clinical characteristics (sex, age, educational background and type of SSc). DIF is tested by assessing item-trait Chi-square interaction statistic and a non-significant Bonferroni-adjusted probability to determine if the tool performs consistently across different subgroups of patients. Principal component analysis and t test-based method was used to assess (strict) unidimensionality of the scale as previously described [24]. This test compares two sets of items hypothesized to represent low levels and high levels of the construct (quality of life), selected based on the correlation between items and the first residual factor. The difference in estimates for each person are compared using an independent t-test. Unidimensionality is confirmed if ≤ 5% of t tests are significant or if the lower bound of a binomial 95% CI of the observed proportion overlap 5% [24]. A p value of < 0.05 was considered significant—except when a Bonferroni adjustment was applied to account for multiple testing (i.e. 0.05/number of tests). IBM® SPSS® Version 26. Armonk, NY: IBM Corp. and RUMM2030 software, Perth, WA: RUMM Laboratory Pty Ltd were used for all quantitative analyses.

Results

Cognitive interviews

A convenience sample of German-speaking patients with SSc from Germany (n = 4) and Switzerland (n = 2) completed the new SScQoL version using “thinking aloud” techniques for cognitive interviews (Additional File 1). Patients identified some problems with item wording and the remaining dichotomous (true/not true) responses. Specifically, participants desired greater differentiation beyond a binary choice (i.e. addition of ‘sometimes’). Based on patient feedback, the expert committee (AK, MN, KH, AR, DN) decided to expand the 4-point response structure to all items. A summary of issues raised for each item during back-translation and cognitive interviews is presented in Additional File 1.

Cross-sectional validation study

Patient characteristics

The validation study sample comprised 78 Swiss-German patients with SSc. They had a median self-reported disease duration (i.e. date of diagnosis) of 8 years (IQR 4–13 years) and the majority, 58/78 (74.7%) were women. Participants’ sociodemographic data are summarized in Table 1. The descriptive results including frequency and distribution of all items are shown in Additional File 2.

Response scale structure

After expanding the response structure, item characteristic curves (ICC) revealed that 22/29 displayed ordered thresholds suggesting that the response categories represented by the thresholds were ordered from low to high (quality of life) as expected (Additional File 3). Collapsing some categories and rescoring items with disordered thresholds improved the individual item fit but not the overall scale.

Fit to the model

Item fit statistics for individual items are shown in Table 2a. Most individual items, appeared to adequately fit the model limits (residuals within the − 2.5 to 2.5 range) with non-significant Chi-Square Bonferroni-adjusted probability (p = 0.0017). The sole exception was item 29 with a fit residual of − 2.573. This may have impacted on the overall validity of the scale (summary statistics indicating deviation from the model) as shown in Table 3 (Chi-Square = 52.198, DF = 29, p = 0.005). When the items were grouped in their respective domains and analysed (Table 2b), each domain was found to adequately fit the model. Summary statics indicate the 5-domain structure has adequate fit to the model (Chi-Square = 5.269, df = 5, p = 0.384) (Table 3). The reliability of the scale was high (PSI = 0.915). The proportion of significant t-tests was < 5% (i.e. 0.0649, 95% CI 0.016–0.114) supporting the unidimensionality of the scale.

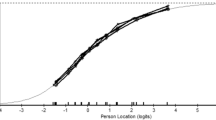

Targeting of persons and items

The revised 29-item German SScQoL version integrating a 4-point response option for all items was shown to cover the full range of participants’ quality of life. The person–item threshold distribution (Fig. 1) depicts that the items are well mapped against all persons.

Invariance of the SScQoL

The test of invariance found that there were no significant DIF by any personal characteristics (age, sex, education level) or disease subcategory and disease duration. The results of DIF analysis are presented in Additional Files 4 and 5.

Testing the fit of the dichotomized scale

As the response structure of the scale has been expanded to 4 responses, comparison of measures with other countries would require a cross-cultural measurement equivalence which may first require dichotomizing responses of the revised scale. For all items, collapsing categories 1, 2 and 3 vs category 4 provided the best model fit in individual items (domains) and the summary statistics (Additional File 6).

Discussion

In the present study, we revised the German SScQoL with the aim to linguistically review the German SScQoL, expand the response structure, and used Rasch analysis to examine construct validity, unidimensionality, and reliability. Overall, the scale was well targeted, had high internal consistency, and worked consistently across patients with varied demographic and clinical characteristics. The present data suggest the revised German SScQoL can now be used with confidence in German-speaking countries.

Cognitive interviews included patients from Germany and Switzerland to gain an understanding of how well patients comprehend the concepts intended by the items and how the new response structure worked for them. Cognitive interviews and subsequent expert discussions revealed translation and language issues that are essential for using the SScQoL in all four German-speaking countries (Austria, Germany, Liechtenstein, Switzerland). We made minor linguistic changes enabling use across German-speaking countries. The initial validation study [13] identified ten items that patients found too restrictive and also lacked fit to the Rasch model. In the present study, cognitive interviews informed modification of the response structure thereby facilitating more accurate responses. Polytomous responses (‘always’, ‘usually’, ‘sometimes’, ‘never’) were applied to all items—although linguistically, this may not always make sense (e.g. for item Q23: ‘I have had to stop some of my hobbies’). Importantly, there is no definitive consensus on the most appropriate translation or questionnaire response format for measuring HRQoL [15]. In the present study, expanding all items to a uniform, 4-point response structure improved the validity and reliability of the German SScQoL. Although there is not necessarily semantic or linguistic equivalence with the English SScQoL, expert meetings and cognitive interviews support conceptual equivalence between the English and German versions.

Rasch analysis confirmed that measurement properties (construct validity, reliability, and unidimensionality) of the SScQoL were retained following its revision in German. Similar to the prior multinational cross-cultural validation using Rasch analysis [13], the SScQoL demonstrated adequate fit when the items were grouped into the five domains. Validity, reliability and unidimensionality of the German SScQoL was demonstrated. Additionally, the tool had good targeting for patients with different levels of HRQoL and was shown to be free of response bias for age, sex, education level, disease subcategory, and disease duration (DIF analysis shown in Additional Files 4 and 5). Overall, fit to the Rasch model confirmed that the measurement properties of the revised German SScQoL version integrating a 4-point response option were retained.

Having a 4-point response structure means that the total score will range from 0 to 87 (i.e. scoring always = 3, usually = 2, sometimes = 1, never = 0) which differs from the original SScQoL (score range: 0–29). For interoperability in research settings, the polytomous scale could be re-scored dichotomously (i.e. ‘always’, ‘usually’ or ‘sometimes’ = ‘true’/1, ‘never’ = ‘not true’/0). We tested this scoring approach and it showed adequate fit to the model (Additional File 6). Instructions for scoring are included in Additional File 7.

The study has several limitations. First, the validation was only planned when the MANOSS project was already established and did not allow for confirmation of the self-reported diagnosis, multiple measurement points and multinational validation [18]. For the cognitive interviews, only six Swiss and German patients were included. Including more patients (i.e. from Austria and Liechtenstein) would have been ideal, although this was not possible. Field testing with more patients from all German-speaking countries could further improve the linguistic presentation of the SScQoL, although we believe conceptual equivalence is more important [15]. Our validation sample only included Swiss German-speaking patients. Thus, caution is warranted when attempting to extend findings to other German-speaking populations. Further studies should include patients from Austria, Germany and Liechtenstein to confirm the robustness of the German SScQoL and ensure transferability. Last, while the instrument is well targeted and the sample size adequate for its validation [25], calibration of the scale into interval-level (transformed) scores was beyond the scope of this study. Future work should include establishing responsiveness of the SScQoL and calibration or cross-cultural comparability studies using data from other European countries.

Conclusions

The data presented herein contributes to the existing literature through the successful revision and validation of the SScQoL, with a new 4-point response structure for the German speaking context. These data are relevant to the broader rare disease research community as they demonstrate that cognitive interviews and Rasch analysis can improve the psychometric properties of PROMs while enabling interoperability of findings. Further cross-cultural validity tests are required to fully demonstrate measurement equivalence with other SScQoL versions, thereby enabling broad, multilinguistic comparison and data pooling. Beyond research, the new German SScQoL is a valid measure that can be used with confidence in clinical practice. The new version of the SScQoL can be obtained at https://doi.org/10.5518/325.

Availability of data and materials

The datasets generated and/or analysed during this study are included in this published article and its supplementary files, or can be made available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

References

Allanore Y, Simms R, Distler O, Trojanowska M, Pope J, Denton CP, et al. Systemic sclerosis. Nature Rev Disease Primers. 2015;1:15002.

Bassel M, Hudson M, Taillefer SS, Schieir O, Baron M, Thombs BD. Frequency and impact of symptoms experienced by patients with systemic sclerosis: results from a Canadian National Survey. Rheumatology (Oxford). 2011;50(4):762–7.

Hudson M, Thombs BD, Steele R, Watterson R, Taillefer S, Baron M, et al. Clinical correlates of quality of life in systemic sclerosis measured with the World Health Organization Disability Assessment Schedule II. Arthritis Rheum. 2008;59(2):279–84.

Decuman S, Smith V, Verhaeghe S, Deschepper E, Vermeiren F, De Keyser F. Work participation and work transition in patients with systemic sclerosis: a cross-sectional study. Rheumatology (Oxford). 2012;51(2):297–304.

Kwakkenbos L, Delisle VC, Fox RS, Gholizadeh S, Jewett LR, Levis B, et al. Psychosocial Aspects of Scleroderma. Rheum Dis Clin North Am. 2015;41(3):519–28.

Hudson M, Thombs BD, Steele R, Panopalis P, Newton E, Baron M, et al. Health-related quality of life in systemic sclerosis: a systematic review. Arthritis Rheum. 2009;61(8):1112–20.

Bretterklieber A, Painsi C, Avian A, Wutte N, Aberer E. Impaired quality of life in patients with systemic sclerosis compared to the general population and chronic dermatoses. BMC Res Notes. 2014;7:594.

Thombs BD, van Lankveld W, Bassel M, Baron M, Buzza R, Haslam S, et al. Psychological health and well-being in systemic sclerosis: State of the science and consensus research agenda. Arthritis Care Res (Hoboken). 2010;62(8):1181–9.

Fischer A, Zimovetz E, Ling C, Esser D, Schoof N. Humanistic and cost burden of systemic sclerosis: a review of the literature. Autoimmun Rev. 2017;16(11):1147–54.

Lizee T, Basch E, Tremolieres P, Voog E, Domont J, Peyraga G, et al. Cost-effectiveness of web-based patient-reported outcome surveillance in patients with lung cancer. J Thorac Oncol. 2019;14(6):1012–20.

Avouac J, Kowal-Bielecka O, Landewe R, Chwiesko S, Miniati I, Czirjak L, et al. European League Against Rheumatism (EULAR) Scleroderma Trial and Research group (EUSTAR) recommendations for the treatment of systemic sclerosis: methods of elaboration and results of systematic literature research. Ann Rheum Dis. 2009;68(5):629–34.

Steen VD, Medsger TA Jr. The value of the Health Assessment Questionnaire and special patient-generated scales to demonstrate change in systemic sclerosis patients over time. Arthritis Rheum. 1997;40(11):1984–91.

Ndosi M, Alcacer-Pitarch B, Allanore Y, Del Galdo F, Frerix M, Garcia-Diaz S, et al. Common measure of quality of life for people with systemic sclerosis across seven European countries: a cross-sectional study. Ann Rheum Dis. 2018;77(7):1032–8.

Reay N. The quality of life in patients with diffuse and limited systemic sclerosis [Monograph]. 2008.

Beaton DE, Bombardier C, Guillemin F, Ferraz MB. Guidelines for the process of cross-cultural adaptation of self-report measures. Spine (Phila Pa 1976). 2000;25(24):3186–91.

Wild D, Grove A, Martin M, Eremenco S, McElroy S, Verjee-Lorenz A, et al. Principles of good practice for the translation and cultural adaptation process for Patient-Reported Outcomes (PRO) measures: report of the ISPOR Task Force for Translation and Cultural Adaptation. Value Health. 2005;8(2):94–104.

Wild D, Eremenco S, Mear I, Martin M, Houchin C, Gawlicki M, et al. Multinational trials-recommendations on the translations required, approaches to using the same language in different countries, and the approaches to support pooling the data: the ISPOR Patient-Reported Outcomes Translation and Linguistic Validation Good Research Practices Task Force report. Value Health. 2009;12(4):430–40.

Kocher A, Simon M, Dwyer AA, Villiger PM, Kunzler-Heule P, De Geest S, et al. Developing a rare disease chronic care model: management of systemic sclerosis (MANOSS) study protocol. J Adv Nurs. 2019;75(12):3774–91.

Tennant A, Conaghan PG. The Rasch measurement model in rheumatology: what is it and why use it? When should it be applied, and what should one look for in a Rasch paper? Arthritis Rheum. 2007;57(8):1358–62.

Hak T, van der Veer K, Jansen H. The Three-Step Test-Interview (TSTI): an observation-based method for pretesting self-completion questionnaires. Surv Res Methods. 2008;2(3).

Hewlett S, Nicklin J, Bode C, Carmona L, Dures E, Engelbrecht M, et al. Translating patient reported outcome measures: methodological issues explored using cognitive interviewing with three rheumatoid arthritis measures in six European languages. Rheumatology (Oxford). 2016;55(6):1009–16.

Oude Voshaar MAH, van de Laar M. Taking the patient and the patient’s perspective into account to improve outcomes of care of patients with musculoskeletal diseases. Best Pract Res Clin Rheumatol. 2019;33(3):101436.

Boone WJ. Rasch Analysis for Instrument Development: Why, When, and How? CBE Life Sci Educ. 2016;15(4):4.

Smith EVJ. Detecting and evaluating the impact of multidimensionality using item fit statistics and principal component analysis of residuals. J Appl Meas. 2002;3(2):205–31.

Linacre JM. Sample size and item calibration stability. Rasch Mes Trans. 1994;7:328.

Acknowledgements

We want to thank all participating patients, rheumatologists, and the Swiss Scleroderma patient association for their good collaboration. Special thanks to Jasmina Bogdanovic, Christel Madelaine-Bonjour, Patricia Steffens-Korbanka, and Sabine Herzig for their valuable support during the validation phase of the questionnaire.

Funding

This publication is part of the Swiss MANagement Of Systemic Sclerosis (MANOSS) cross-sectional study and was funded by the Swiss Nursing Science Foundation and the Swiss League Against Rheumatism.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

AK, MN, MS, and DN conceived and designed the work. AK and KH acquired and analyzed the data of the first study phase. AK, OD, PMV, and UAW acquired the data of the second study phase, and MN and KD analyzed the data. AK, MN, KD, MS, AD, and DN contributed to interpreting the data and drafting the manuscript. All authors revised the subsequent drafts critically for important intellectual content. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

The Swiss MANagement Of Systemic Sclerosis (MANOSS) cross-sectional study was reviewed and approved by the responsible Swiss ethics committee in September 2018 (EKNZ 2018‐01206). Patient information forms and informed consent documents complied with the Swiss ethics committee’s templates. All participants received a written explanation of the purpose of the study, the voluntary nature of their participation and the use of their contributions.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

Agnes Kocher has received financial support from the Swiss Nursing Science Foundation, from the Swiss League Against Rheumatism, and from the University of Basel for her dissertation and from Sandoz to support the development of an eLearning module for patients with rheumatic diseases. She is an unpaid member of the EULAR recommendations for non-pharmacological management of autoimmune connective tissue diseases task force. Oliver Distler declares consultancy relationship and/or research funding in the area of potential treatments of systemic sclerosis and its complications from: Abbvie, Actelion, Acceleron Pharma, Amgen, AnaMar, Baecon Discovery, Blade Therapeutics, Bayer, Boehringer Ingelheim, Catenion, Competitive Corpus, Drug Development International Ltd, CSL Behring, ChemomAb, Ergonex, Galapagos NV, Glenmark Pharmaceuticals, GSK, Horizon (Curzion) Pharmaceuticals, Inventiva, Italfarmaco, iQone, iQvia, Kymera Therapeutics, Lilly, medac, Medscape, Mitsubishi Tanabe Pharma, MSD, Novartis, Pfizer, Roche, Sanofi, Target Bio Science and UCB. Patent mir-29 for the treatment of systemic sclerosis issued (US8247389, EP2331143). Andrew A. Dwyer, Kirsten Hoeper, Patrizia Künzler-Heule, Mwidimi Ndosi, Dunja Nicca, Anthony C. Redmond, Michael Simon, Kris Denhaerynck, Peter M. Villiger and Ulrich A. Walker declare they have no financial and non-financial interests that are directly or indirectly related to this work.

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary Information

Additional File 1

. Back-translation, issues and agreements for each item of the German Systemic Sclerosis Quality of Life Questionnaire (SScQoL).

Additional File 2

. Frequency and level of quality of life of all items of the new German Systemic Sclerosis Quality of Life Questionnaire (SScQoL) version (N = 78).

Additional File 3

. Item characteristic curves (ICC) for all items.

Additional File 4

. Differential item functioning (DIF) analysis A.

Additional File 5

. Differential item functioning (DIF) analysis B.

Additional File 6

. Testing the dichotomized responses.

Additional File 7

. Scoring instructions for the new German version of the Systemic Sclerosis Quality of Life (SScQoL) questionnaire.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/. The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver (http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/) applies to the data made available in this article, unless otherwise stated in a credit line to the data.

About this article

Cite this article

Kocher, A., Ndosi, M., Denhaerynck, K. et al. A rare disease patient-reported outcome measure: revision and validation of the German version of the Systemic Sclerosis Quality of Life Questionnaire (SScQoL) using the Rasch model. Orphanet J Rare Dis 16, 356 (2021). https://doi.org/10.1186/s13023-021-01944-9

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s13023-021-01944-9