Abstract

Background

Spinal muscular atrophy (SMA) is a neurodegenerative disease that has a substantial and multifaceted burden on affected adults. While advances in supportive care and therapies are rapidly reshaping the therapeutic environment, these efforts have largely centered on pediatric populations. Understanding the natural history, care pathways, and patient-reported outcomes associated with SMA in adulthood is critical to advancing health policy, practice and research across the disease spectrum. The aim of this study was to systematically review research investigating the healthcare, well-being and lived experiences of adults with SMA.

Methods

In accordance with the Preferred Reported Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analysis guidelines, seven electronic databases were systematically searched until January 2020 for studies examining clinical (physical health, natural history, treatment) and patient-reported (symptoms, physical function, mental health, quality of life, lived experiences) outcomes in adults with SMA. Study risk of bias and the level of evidence were assessed using validated tools.

Results

Ninety-five articles met eligibility criteria with clinical and methodological diversity observed across studies. A heterogeneous clinical spectrum with variability in natural history was evident in adults, yet slow declines in motor function were reported when observational periods extended beyond 2 years. There remains no high quality evidence of an efficacious drug treatment for adults. Limitations in mobility and daily activities associated with deteriorating physical health were commonly reported, alongside emotional difficulties, fatigue and a perceived lack of societal support, however there was no evidence regarding effective interventions.

Conclusions

This systematic review identifies the many uncertainties regarding best clinical practice, treatment response, and long-term outcomes for adults with SMA. This comprehensive identification of the current gaps in knowledge is essential to guide future clinical research, best practice care, and advance health policy with the ultimate aim of reducing the burden associated with adult SMA.

Similar content being viewed by others

Background

Management of SMA in adulthood has traditionally been limited to long-term multidisciplinary medical and supportive care to maintain functional mobility, independence and quality of life [1,2,3], favorably altering natural history [4]. Since 2017, there have been major transformations in medical therapy for pediatric SMA, including two Federal Drug Administration approved disease-modifying treatments [5,6,7,8]. Notwithstanding these milestones, there remain many uncertainties regarding treatment response, effects and long-term outcomes across this diverse clinical population, particularly for adults with SMA [9].

Clinically, SMA is characterized by progressive muscle weakness and atrophy due to degeneration of motor neurons of the spinal cord and cranial motor nuclei [2]. This neurodegeneration is caused by a homozygous deletion or mutation of the “Survival of Motor Neuron 1” (SMN1) gene [10, 11], with a pan-ethnic incidence of 1 per 11,000 live births and a prevalence of around 1–2 per 100,000 persons [12, 13]. The clinical phenotype has a broad spectrum of severity which is classified based on age of onset and maximal motor milestone achieved: people with SMA type I have symptom onset within 6 months and never attain independent sitting; people with SMA type II have onset between 6 and 18 months and achieve unassisted sitting but not independent walking; people with SMA type III have onset between 18 months-18 years and attain the ability to walk unaided; people with SMA type IV have onset > 18 years.

The health of adults diagnosed with SMA extends from the physical impact to their mental and social well-being, highlighting the importance of a comprehensive and interdisciplinary approach for clinical care and research [1, 3, 14]. Although it is estimated that adults comprise more than 25% of the global SMA patient population [15], reports have documented differences in clinical and supportive care, as well as challenges in accessing new therapies and research [16, 17]. Thus, the purpose of this scoping review was to synthesize and critically appraise the available evidence on the natural history, clinical management, physical and mental health, quality of life, and lived experiences of adults with SMA to advance future health policy, practice and research.

Methods

Search strategy and selection criteria

A scoping review systematically charts diverse bodies of evidence to identify key concepts and gaps in research [18]. The Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA) guidelines were followed to identify and screen scientific literature published in English, and extract data [19]. A comprehensive search was performed using seven electronic databases (Medline, PsycINFO, Scopus, Embase, CINAHL, ProQuest, Cochrane) from inception to January 20 2020 and limited to human studies. Ancestry methods, citation chaining and prolific author searching were used to identify additional articles up until the point of manuscript submission. Search terms included “spinal muscular atrophy”, “adult”, “adolescent”, “patient”, “family”, “lived experience”, “quality of life”, “patient perspective”, “mental health”, “adaptation, psychological”, “natural history”, “treatment”, “care”, “activities of daily living”, “living conditions” and “patient experiences”.

Studies involving adults (for the purposes of this review, adult was considered anyone over the age of 17 years) diagnosed with SMA were included for review if they described the (i) clinical characteristics or natural history of SMA; (ii) clinical management or treatment; or (iii) perspectives of adults with SMA regarding their health and well-being or lived experiences. Studies with mixed samples where outcomes for adults with SMA were not reported separately or could not be calculated, non-peer reviewed articles, and publications in a non-English language were excluded. After removal of duplicates, two reviewers (HW, KC) independently screened titles and abstracts for eligibility. The full-text of studies assessed as potentially relevant were independently evaluated by two reviewers (HW, KC). Differences in evaluation were resolved through consensus or consultation with a third reviewer (MF).

Data extraction

Data extraction was carried out by one of three authors (HW, KC, AD) using a standardized data collection form, and checked for accuracy and completeness by a second author. Extracted data included study and sample characteristics, intervention and comparator details, outcomes measured and results, as relevant to the current review.

Assessment of bias and quality of evidence

Eligible original research articles (excluding case series or case studies) were rated using the QualSyst tool independently by two reviewers (HW, KC, and/or AD) [20]. QualSyst is a standardized, reproducible and quantitative means of simultaneously assessing the quality of research, suitable for use with a broad range of study designs (quantitative and qualitative). Quality is defined in terms of the internal validity of studies, or extent to which the design, conduct and analyses minimize errors and biases, yielding a score between 0 and 1 for each study, with higher scores indicating lower risk of bias and thus greater methodological rigor (> 0.8 = ‘Strong’, 0.71–0.79 = ‘Good’, 0.50–0.70 = ‘Adequate’, < 0.50 = ‘Limited’). The QualSyst score was not used to limit articles for the review. In addition, for each of the main areas of clinical management [1, 3], ratings of the level of evidence were undertaken utilizing the Oxford Centre for Evidence-based Medicine for ratings of individual studies [21].

Data synthesis and analysis

The studies were categorized based on reporting clinical (disease manifestation, natural history, management) or patient-reported outcomes (physical symptoms and function, mental health and psychosocial well-being and social participation) for adults with SMA. The primary reporting methods was narrative synthesis. Statistical synthesis using meta-analysis was not considered informative, given the small number of studies for each category and disparate methods, outcome measures, and study designs.

Results

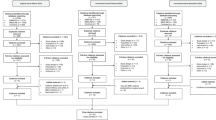

The search of databases, citations and reference lists yielded 4057 records. Following removal of duplicates (n = 1104), 2965 titles and abstracts were screened, and the full-text of 701 articles reviewed with 95 articles meeting all eligibility criteria (see Fig. 1). This comprised 62 quantitative, 9 qualitative, 4 mixed methods studies, 16 case series/reports, and 4 consensus statements on standards of care.

Clinical characteristics of SMA in adulthood

Physical symptoms for adults with SMA included limitations in muscle strength, mobility and posture, and respiratory and bulbar function [2, 22,23,24,25,26,27]. The magnitude of these limitations varied among adults with different SMA types [27]. Hip dislocation or subluxation has been reported in approximately 33% of people with SMA type II or III in long-term follow-up [28].

Natural history

Of the 19 studies that examined the natural history of SMA during adulthood (Table 1), muscle strength or motor function was the primary outcome in 14 studies. Comparisons of muscle strength and motor function between younger (children and adolescents) and older (adult) individuals with the same SMA phenotype in cross-sectional studies demonstrated significant differences in muscle strength and loss of motor skills over time [22, 30, 32, 36, 39, 41, 42, 45,46,47]. The estimated rate of muscle strength decline was determined in one cross-sectional study, with mean annual losses of 1 point for the summative Medical Research Council (MRC) score and 0.5 for the Hammersmith Functional Motor Scale Expanded (HFMSE) [22]. Five studies have assessed ambulatory status with the probability of continued ambulation at 20 years of age ranging between 16 and 33.5% for SMA type IIIa and 84–100% for SMA IIIb [29, 30, 32]. Whilst the probability of ambulation either after age 40 years or 40 years post onset ranged from 22 to 45% for SMA type IIIa (onset < 3 years) and 50–68% for SMA type IIIb (onset > 3 years) [29,30,31, 41]. Variability in the results of prospective longitudinal studies measuring motor function and/or strength were evident with two studies showing no change [33, 37], while others demonstrated gradual decline, particularly when observational periods extended beyond 2 years [26, 34,35,36, 38,39,40,41,42,43]. Separately, functional decline was not solely related to muscle weakness, with factors such as disuse atrophy, contractures and co-morbidities identified as contributing to loss of function [42, 48,49,50]. Considerable differences between study designs (9 prospective, 7 retrospective, and 3 cross-sectional), participant characteristics (N:10–240, types of SMA, disease duration), primary outcome (survival, strength or motor function), length of follow up (0–17 years) and documentation of comorbidities limited the analysis of study findings for differences in the rate of deterioration of muscle strength between SMA types with age.

Clinical management

Forty-six of the 95 captured articles examined clinical care of SMA in adults. Although the established standards of care for SMA have primarily focused on children with severe phenotypes [1, 36], clinical management for adults with SMA remains multidisciplinary, ideally in a specialized services incorporating nutritional, respiratory, orthopedic, and rehabilitation care. Four studies reported feeding and swallowing difficulties resulting from bulbar weakness in adults with SMA. Difficulties included reduced bite force, increased masticatory muscle fatigue and difficulties with mouth opening, together prolonging meal times [51] and adversely impacting nutritional intake [27, 52, 53]. Conversely, in a cohort of non-ambulatory, high-functioning people with SMA, 71% had a fat max index (fat mass/height2, estimated using dual energy X-ray absorptiometry) >85th percentile for age and gender compared to 47% of low-functioning, non-ambulatory and 47% of ambulatory SMA patients [54]. Six studies measured respiratory function in 321 adults with SMA and showed slow and progressive decreases in respiratory capacity [55,56,57] and earlier, more rapid progression of respiratory dysfunction in adults with SMA type II [34, 58]. Stratification of SMA III by subtype suggested respiratory function in type IIIa SMA was similar to SMA type II whilst respiratory function in type IIIb and IV patients was comparable to age-matched healthy controls [33, 57]. Despite this and consensus on recommendations for the monitoring and initiation of respiratory support [1, 59], respiratory management remains variable [17, 60]. Recommendations for rehabilitation therapy such as physical therapy were described in the 2018 standards of care' [3], yet the effect of these recent guidelines in the care of people with SMA is not yet known. In an earlier study, half of adults (n = 19, United States) reported receiving only one physical therapy service on average per month [61], and there was no literature evaluating the impact of such services. Case reports described development of assistive technology trialed by 11 adults with SMA and severe motor disabilities, which included an upper limb assistive exoskeleton, eye tracking system and computer assisted robot, with enhanced functionality in self-feeding and communication reported [62,63,64,65].

Medications

Five randomized placebo controlled clinical trials and three open label trials evaluated medications (valproic acid, gabapentin, salbutamol, hydroxyurea and nusinersen) in adults with SMA type II and III (n = 362 participants, follow up 6–12 months), using different measures of muscle strength and function: four showed no statistically significant effects on the outcome measures, and an open label study of nusinersen showed mean improvement of 8.25 m in the 6 min walk test (p = 0.01), Taken together these were rated as providing Level 1–4 evidence (Table 2) on the Oxford Centre for Evidence-based Medicine scale. Seven case series reported administration of intrathecal nusinersen, with radiological guidance an option for administration, using transforaminal or interlaminar approaches +/− laminotomy [89,90,91,92,93,94,95]. Lumbar punctures were mostly well tolerated, adverse events included post lumbar headache and subarachnoid haemorrhage.

There was no literature that described mental health care for adults with SMA or evaluated transition into the adult service. Palliative care services for adults with SMA have been described in two studies; however, limited evidence suggests a lack of co-ordination in the provision of such care [96, 97]. Routine cardiac surveillance was not endorsed; two studies suggested that cardiac abnormalities were uncommon in type in SMA II and III patients [98, 99]. Four case series reported successful pregnancies among 39 adults with SMA [100,101,102,103]. One of these compared the incidences of obstetric complications to those in the normal population, and found statistically significant increased rates for preterm deliveries (29.4%) and caesarean sections (42%) [100].

Lived experiences and patient-reported outcomes associated with SMA in adults

Twenty one of the 95 captured studies investigated the experiences of adults with SMA; 13 studies used a quantitative methodology (n = 1491), 6 used a qualitative methodology (n = 102), and 2 used mixed methods (n = 111).

Physical symptoms and function

Physical health and functioning were measured in 3 studies using validated patient-reported quality of life measures (e.g. Short Form Health Survey, RAND-36) and all reported significantly lower ratings of health-related quality of life in the physical domain compared to published healthy reference populations [61, 104, 105]. Physical quality of life (QoL) significantly correlated with disease severity. Adults with SMA perceived limitations in physical functioning and ability to perform daily actions, especially independence in self-feeding, using the restroom and performing transfers, had the greatest impact on general well-being [27, 60, 67,68,69, 104,105,106,107,108]. One mixed methods study reported that women tended to prioritize the importance of certain activities (e.g. personal hygiene, eating) more than men, whilst the ability to utilize one’s hands and fingers was perceived as important by both genders [68]. People with SMA universally stated that maintaining stability of their current functional ability was important [60, 109]. One example was that small changes in being able to move one’s finger half an inch could be the difference between being able to operate a power wheelchair or not [109]. People with SMA described strategies to minimize the impact of mobility limitations, including the use of assistive devices, conserving energy for specific tasks, maximizing utility, pro-active health management, nutrition optimization, and minimizing exposure to infection [70]. Devices which improved independence, such as power wheelchairs and upper or lower limb orthoses, were highly valued [66].

Frequency and severity of bodily pain was measured in three questionnaires: in two customized surveys prevalence was 50–70% and rated as having a mild to moderate effect on life, compared to two studies using validated the short form health survey that reported no difference in bodily pain scores against the general population [27, 106, 110, 111]. Bodily pain was moderately associated with global ratings of life satisfaction [110].

Psychosocial wellbeing

Mental health and psychosocial functioning were measured in adults with SMA in 9 studies (5 undertaken in The Netherlands) using 10 different validated patient report measures (e.g. Short form Health Survey, RAND 36, NMS Quest) and two customized surveys) [27, 104, 105, 108, 111,112,113,114]. Compared to published healthy age-matched reference populations, ratings of health-related quality of life in the mental domain were higher or similar [104, 105, 108], and ratings of psychological well-being, self-esteem, satisfaction with life and emotional functioning were similar. Subjective feelings of depression and anxiety were low in adults with SMA [112], yet correlated with feelings of fatigue [111]. Three of the 19 studies found an association between less severe physical limitations, for example ambulation, and more emotional distress [105, 111, 113]. Perceptions of fatigue were universal and not associated with physical function, health related quality of life or fatigability in another study [115]. For adults with poorer physical function, engagement with a patients’ association was associated with greater psychosocial wellbeing [114]. In a recent survey of 82 adults with SMA in the United Kingdom, 79% of participants agreed or strongly agreed that “people with SMA can live a fulfilling life” and 52% endorsed the statement, “having SMA causes people to suffer”. Only 29% of participants in this study perceived their health as ‘good’ [113]. Prevalence of non-specific “emotional issues” was 60% and average effect on daily life was rated as mild to moderate in a second customized questionnaire of 99 adults with SMA, with 80% also reporting impaired body image due to disease [27, 67].

The lived experience of 127 adults with SMA interviewed across 9 studies provides further insights into emotional and social well-being. (Table 3) The factors identified as important to psychological well-being included autonomy, competence and social participation along with resilience, determination, hope and an optimistic view of life [69, 70, 117]. The major emotional challenges voiced by people with SMA were coping with frustration, guilt and stress alongside desire for independence [67,68,69]. Fear of functional decline and premature death were also expressed in 6 studies, associated with the need to make difficult treatment decisions and readjust future hopes, expectations and goals [69, 70, 105, 116,117,118]. Physical decline following long periods of stability was associated with emotional distress [117, 118]. Participants in one study described unmet physical and psychological care needs in addition to difficulties associated with accessing appropriate adult healthcare services [117].

Experiences and participation in social activities

Adults with SMA perceived employment opportunities, economic independence and autonomy as key priorities [116], yet two thirds noted restrictions in work and education [111]. Six studies reported 33–66% of adults with SMA completed tertiary education [27, 68, 69, 108, 111, 119]. Full-time employment rates were reported to range from 18 to 49%, with most adults with SMA engaged in part-time employment [27, 68, 104, 108, 111, 119]. Reduced work hours have been associated with greater deterioration of motor function [119]. One-quarter to 61% of adults with SMA reported having a romantic partner or spouse; people with greater severity of symptoms were less likely to have a partner [68, 106, 108, 111, 119].

Socially, a majority of people with SMA reported experiencing stigma, challenges to integrating into mainstream society and participating in normal activities, with 62–72% of people reporting decreased satisfaction and 66–72% reporting restrictions and performance in social situations [27, 111]. People with early onset SMA (SMA I, II, and IIIa) reported significantly more participation restrictions compared to with people with late onset SMA (SMA IIIb and IV) [27, 111]. Some people with SMA have noted only feeling that their disease was an issue when there was a lack of facilities to allow them to engage with normal activities [118]. In one survey, only 15% of adults with SMA agreed with the question “people with SMA are well supported by society” [113]. Frequently environmental barriers presented limitations, including a lack of accessible bathrooms or wheelchair access [116]. Supportive family, friends and community members were identified as key facilitators of positive coping and engagement [69, 70]. Despite restrictions in daily activities, another study found adults with SMA were very satisfied with participation in social activities [108], and regression analyses demonstrated that 30–50% of variance in psychological well-being was explained by participant’s societal participation and satisfaction for basic psychological needs. Another study showed frequency of participation in daily life correlated with pain, feelings of depression and fatigue [111].

Risk of bias and quality of evidence

Methodological rigor across 78% of studies was ‘good’ or ‘strong’, with a median QualSyst score of 0.79 (Range 0.36–1.00; interquartile range 0.14). Evidence related to clinical care of SMA in adults was rated as generally poor (Level 4 or 5) [21]. Synthesizing studies assessing patient experience or patient-reported outcomes, risk of selection bias was high often due to the recruitment strategy adopted (e.g., opt in) or participant characteristics (e.g., under-representation of people with lower levels of educational attainment), information bias was modest due to use of non-validated survey instruments in several studies and potential concerns with generalizability were evident with 6/20 studies undertaken in The Netherlands.

Discussion

Adults living with SMA face multi-dimensional challenges which encompass physical, psychological, social, financial and practical domains. Significant barriers exist for adults with SMA, limiting engagement with health care, and access to therapeutic interventions that aim to maintain stability, promote function and enhance quality of life [109]. The dynamic and rapidly changing SMA therapeutic landscape in pediatric patients serves to emphasize the importance of providing high quality evidence-based healthcare to optimize translation in the large population of adults living with SMA. However, the care and support needs, disease progression, mental health and social well-being of adults living with SMA is largely understudied. This systematic review is required to address this knowledge gap by comprehensively reviewing the available scientific literature for the purposes of guiding and extending translational research to address uncertainties across the broader population of adults with SMA regarding clinical course, impact and therapeutic response, together with elucidation of optimal supportive care.

Access to and reimbursement of expensive therapies for rare diseases relies heavily on the demonstration of tangible benefits and the evaluation of cost-effectiveness. The considerable heterogeneity and slow disease progression in adults with SMA has contributed to the paucity of research and lack of efficacy in the limited number of trials to date. Clinical trials which could address this issue require long durations and robust clinical outcome measures, drawing attention to the need for biomarkers which are sensitive to changes in disease progression and/or response to disease modifying agents [120]. Unlike studies in infants and children with SMA, in which circulating neurofilaments are emerging as potential measures to assess disease progression and response to nusinersen treatment [121], no studies in adults with SMA have yielded a robust, reliable measurement [86, 88, 122,123,124,125,126]. A potential complexity in trying to detect elevated markers of axonal degradation in adults with SMA is again the slow rate of progression. The structure of such clinical trials also requires further understanding of pathophysiology in order to direct and justify continued research. Understanding the natural history of the various adult SMA subtypes is a key step in evaluating the efficacy and value of emerging disease modifying therapies. Whilst several natural history studies have been conducted to evaluate motor strength progression in adults [22, 26, 29, 34, 36, 38, 41], the phenotypic variability, slow disease progression and sensitivity of outcome measures make it hard to compare and draw definitive conclusions. Optimizing the effectiveness of outcome measures remains a key issue, particularly in light of the significant benefit in quality of life derived from small changes in function in adults with SMA [109].

While awaiting the emergence of future disease modifying therapies [8, 127], it is vital that practitioners are aware of the range of supportive care options available for adults, strengthened by the generation of high-quality evidence. It is essential for future consensus guidelines to include a specific focus on the management of adults with SMA. Functional classification of adult phenotypes, incorporating changes with disease progression and encompassing the adult spectrum of severity, may better describe appropriate care and support requirements (Table 4). Integrating transitional care in neuromuscular clinics and elucidation of best practices may reduce the potential for poorer objective health outcomes, health service use and loss to follow-up shown in other chronic health conditions associated with poorly managed transitions [128].

The experience, perceptions and involvement of adults with SMA is essential in future research, provision of health care and policy to drive more meaningful and patient centered outcomes. Studies incorporating the perspectives and experiences of adults with SMA are increasing our understanding of the impact of SMA on quality of life, mental health, emotional and social functioning. Clinically, periods of significant change in physical ability are associated with distress, however mental health does not have a linear association with severity of physical disability, indeed those with milder phenotypes have reported greater difficulties. Characterizing potential determinants of quality of life, emotional issues and deficiencies in social support are a first step toward developing evidence-based psychosocial care.

Conclusions

SMA has multidimensional medical, psychological, social and practical implications for adults. Despite an established evidence base for clinical care of SMA in children, this review highlights the significant knowledge gaps in best practice management, patterns of treatment response, and disease progression in adults with SMA. From existing research, adults with SMA experience limitations in mobility and daily activities associated with a gradual deterioration in motor function, alongside emotional difficulties, fatigue and a perceived lack of societal support, however there was no evidence regarding effective interventions. Psychological well-being was important for adults with SMA, however there was limited data regarding prevalence and burden of mental health with no high quality evidence regarding effective interventions. Identifying gaps in knowledge is essential to guide future clinical research, best practice care, and advance health policy with the ultimate aim of reducing the burden associated with adult SMA.

Availability of data and materials

The datasets used and/or analysed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

Abbreviations

- 6MWT:

-

Six-minute walk test

- EK:

-

Egen Klassifikation;

- FVC:

-

Forced vital capacity

- GMFM:

-

Gross motor function measure

- HFMS:

-

Hammersmith functional motor scale

- HFMSE:

-

Hammersmith functional motor scale expanded

- MFM:

-

Motor function measure

- MI-E:

-

Mechanical insufflation-exsufflation

- MMT:

-

Manual muscle testing

- MRC:

-

Medical Research Council

- PRISMA:

-

Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic reviews and Meta-Analyses

- QoL:

-

Quality of life

- RULM:

-

Revised Upper Limn Module

- SMA:

-

Spinal muscular atrophy

- TMS:

-

Total muscle score

- ULM:

-

Upper limb module

- VO2Max:

-

Maximal oxygen uptake

References

Finkel RS, Mercuri E, Meyer OH, Simonds AK, Schroth MK, Graham RJ, et al. Diagnosis and management of spinal muscular atrophy: part 2: pulmonary and acute care; medications, supplements and immunizations; other organ systems; and ethics. Neuromuscul Disord. 2018;28(3):197–207.

Wang CH, Finkel RS, Bertini ES, Schroth M, Simonds A, Wong B, et al. Consensus statement for standard of care in spinal muscular atrophy. J Child Neurol. 2007;22(8):1027–49. https://doi.org/10.1177/0883073807305788.

Mercuri E, Finkel RS, Muntoni F, Wirth B, Montes J, Main M, et al. Diagnosis and management of spinal muscular atrophy: part 1: recommendations for diagnosis, rehabilitation, orthopedic and nutritional care. Neuromuscul Disord. 2018;28(2):103–15.

Markowitz JA, Singh P, Darras BT. Spinal muscular atrophy: a clinical and research update. Pediatr Neurol. 2012;46(1):1–12. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.pediatrneurol.2011.09.001.

Finkel RS, Mercuri E, Darras BT, Connolly AM, Kuntz NL, Kirschner J, et al. Nusinersen versus sham control in infantile-onset spinal muscular atrophy. N Engl J Med. 2017;377(18):1723–32.

Hoy SM. Onasemnogene Abeparvovec: first global approval. Drugs. 2019. https://doi.org/10.1007/s40265-019-01162-5.

Mercuri E, Darras BT, Chiriboga CA, Day JW, Campbell C, Connolly AM, et al. Nusinersen versus sham control in later-onset spinal muscular atrophy. N Engl J Med. 2018;378(7):625–35.

Hoy SM. Nusinersen: first global approval. Drugs. 2017;77(4):473–9. https://doi.org/10.1007/s40265-017-0711-7.

Corey DR. Nusinersen, an antisense oligonucleotide drug for spinal muscular atrophy. Nat Neurosci. 2017;20(4):497.

Lefebvre S, Burlet P, Liu Q, Bertrandy S, Clermont O, Munnich A, et al. Correlation between severity and SMN protein level in spinal muscular atrophy. Nat Genet. 1997;16(3):265.

Lefebvre S, Bürglen L, Reboullet S, Clermont O, Burlet P, Viollet L, et al. Identification and characterization of a spinal muscular atrophy-determining gene. Cell. 1995;80(1):155–65.

Sugarman EA, Nagan N, Zhu H, Akmaev VR, Zhou Z, Rohlfs EM, et al. Pan-ethnic carrier screening and prenatal diagnosis for spinal muscular atrophy: clinical laboratory analysis of> 72 400 specimens. Eur J Hum Genet. 2012;20(1):27.

Verhaart IEC, Robertson A, Wilson IJ, Aartsma-Rus A, Cameron S, Jones CC, et al. Prevalence, incidence and carrier frequency of 5q–linked spinal muscular atrophy – a literature review. Orphanet J Rare Dis. 2017;12:124. https://doi.org/10.1186/s13023-017-0671-8.

Farrar MA, Carey KA, Paguinto S-G, Chambers G, Kasparian NA. Financial, opportunity and psychosocial costs of spinal muscular atrophy: an exploratory qualitative analysis of Australian carer perspectives. BMJ Open. 2018;8(5):e020907.

Verhaart I, Robertson A, Leary R, McMacken G, König K, Kirschner J, et al. A multi-source approach to determine SMA incidence and research ready population. J Neurol. 2017;264(7):1465–73. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00415-017-8549-1.

Madipalli S. Spinraza—the patient perspective. Gene Ther. 2017;24(9):501.

Bladen CL, Thompson R, Jackson JM, Garland C, Wegel C, Ambrosini A, et al. Mapping the differences in care for 5,000 spinal muscular atrophy patients, a survey of 24 national registries in North America, Australasia and Europe. J Neurol. 2014;261(1):152–63.

Arksey H, O'Malley L. Scoping studies: towards a methodological framework. Int J Soc Res Methodol. 2005;8(1):19–32. https://doi.org/10.1080/1364557032000119616.

Moher D, Shamseer L, Clarke M, Ghersi D, Liberati A, Petticrew M, et al. Preferred reporting items for systematic review and meta-analysis protocols (PRISMA-P) 2015 statement. Syst Rev. 2015;4(1):1.

Kmet LM, Lee RC, Cook LS. Standard quality assessment criteria for evaluating primary research papers from a variety of fields. Edmonton: Alberta Heritage Foundation for Medical Research (AHFMR)AHFMR - HTA Initiative #13; 2004.

Oxford Centre for Evidence-Based Medicine. The Oxford 2011 Levels of Evidence.https://www.cebm.net/2016/05/ocebm-levels-of-evidence/.

Wadman R, Wijngaarde C, Stam M, Bartels B, Otto L, Lemmink H, et al. Muscle strength and motor function throughout life in a cross-sectional cohort of 180 patients with spinal muscular atrophy types 1c–4. Eur J Neurol. 2018;25(3):512–8.

van der Heul AMB, Wijngaarde CA, Wadman RI, Asselman F, van den Aardweg MTA, Bartels B, et al. Bulbar problems self-reported by children and adults with spinal muscular atrophy. J Neuromuscul Dis. 2019;6(3):361–8. https://doi.org/10.3233/jnd-190379.

Peeters LHC, Janssen M, Kingma I, van Dieen JH, de Groot IJM. Patients with spinal muscular atrophy use high percentages of trunk muscle capacity to perform seated tasks. Am J Phys Med Rehabil. 2019;98(12):1110–7. https://doi.org/10.1097/phm.0000000000001258.

Febrer A, Rodriguez N, Alias L, Tizzano E. Measurement of muscle strength with a handheld dynamometer in patients with chronic spinal muscular atrophy. J Rehabil Med. 2010;42(3):228–31.

Deymeer F, Serdaroglu P, Parman Y, Poda M. Natural history of SMA IIIb: muscle strength decreases in a predictable sequence and magnitude. Neurology. 2008;71(9):644–9. https://doi.org/10.1212/01.wnl.0000324623.89105.c4.

Mongiovi P, Dilek N, Garland C, Hunter M, Kissel JT, Luebbe E, et al. Patient reported impact of symptoms in spinal suscular atrophy (PRISM-SMA). Neurology. 2018;91(13):e1206–e14. https://doi.org/10.1212/wnl.0000000000006241.

Sporer SM, Smith BG. Hip dislocation in patients with spinal muscular atrophy. J Pediatr Orthop. 2003;23(1):10–4.

Zerres K, Rudnik-Schoneborn S, Forrest E, Lusakowska A, Borkowska J, Hausmanowa-Petrusewicz I. A collaborative study on the natural history of childhood and juvenile onset proximal spinal muscular atrophy (type II and III SMA): 569 patients. J Neurol Sci. 1997;146(1):69–72.

Zerres K, Rudnik-Schöneborn S. Natural history in proximal spinal muscular atrophy. Clinical analysis of 445 patients and suggestions for a modification of existing classifications. Arch Neurol. 1995;52(5):518–23.

Chung BHY, Wong VCN, Ip P. Spinal muscular atrophy: survival pattern and functional status. Pediatrics. 2004;114(5):e548–e53. https://doi.org/10.1542/peds.2004-0668.

Farrar MA, Vucic S, Johnston HM, Du Sart D, Kiernan MC. Pathophysiological insights derived by natural history and motor function of spinal muscular atrophy. J Pediatr. 2013;162(1):155–9. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jpeds.2012.05.067.

Piepers S, van den Berg LH, Brugman F, Scheffer H, Ruiterkamp-Versteeg M, van Engelen BG, et al. A natural history study of late onset spinal muscular atrophy types 3b and 4. J Neurol. 2008;255(9):1400–4. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00415-008-0929-0.

Kaufmann P, McDermott MP, Darras BT, Finkel RS, Sproule DM, Kang PB, et al. Prospective cohort study of spinal muscular atrophy types 2 and 3. Neurology. 2012;79(18):1889–97.

Pera MC, Coratti G, Mazzone ES, Montes J, Scoto M, De Sanctis R, et al. Revised upper limb module for spinal muscular atrophy: 12 month changes. Muscle Nerve. 2019;59(4):426–30. https://doi.org/10.1002/mus.26419.

Mercuri E, Finkel R, Montes J, Mazzone ES, Sormani MP, Main M, et al. Patterns of disease progression in type 2 and 3 SMA: implications for clinical trials. Neuromuscul Disord. 2016;26(2):126–31.

Sivo S, Mazzone E, Antonaci L, De Sanctis R, Fanelli L, Palermo C, et al. Upper limb module in non-ambulant patients with spinal muscular atrophy: 12 month changes. Neuromuscul Disord. 2015;25(3):212–5.

Werlauff U, Vissing J, Steffensen B. Change in muscle strength over time in spinal muscular atrophy types II and III. A long-term follow-up study. Neuromuscul Disord. 2012;22(12):1069–74.

Montes J, McDermott MP, Mirek E, Mazzone ES, Main M, Glanzman AM, et al. Ambulatory function in spinal muscular atrophy: age-related patterns of progression. PLoS One. 2018;13(6):e0199657. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0199657.

Vuillerot C, Payan C, Iwaz J, Ecochard R, Bérard C, Group MSMAS. Responsiveness of the motor function measure in patients with spinal muscular atrophy. Arch Phys Med Rehabil. 2013;94(8):1555–61.

Russman B, Buncher C, White M, Samaha F, Iannaccone S. Function changes in spinal muscular atrophy II and III. Neurology. 1996;47(4):973–6.

Iannaccone ST, Russman BS, Browne RH, Buncher CR, White M, Samaha FJ. Prospective analysis of strength in spinal muscular atrophy. J Child Neurol. 2000;15(2):97–101.

Carter GT, Abresch RT, Fowler JW, Johnson ER, Kilmer DD, McDonald CM. Profiles of neuromuscular diseases. Spinal muscular atrophy. Am J Phys Med Rehabil. 1995;74(5 Suppl):S150–9.

Durmus H, Yilmaz R, Gulsen-Parman Y, Oflazer-Serdaroglu P, Cuttini M, Dursun MU, et al. Muscle magnetic resonance imaging in spinal muscular atrophy type 3: selective and progressive involvement. Muscle Nerve. 2017;55(5):651–6. https://doi.org/10.1002/mus.25385.

Werlauff U, Steffensen B, Bertelsen S, Fløytrup I, Kristensen B, Werge B. Physical characteristics and applicability of standard assessment methods in a total population of spinal muscular atrophy type II patients. Neuromuscul Disord. 2010;20(1):34–43.

Merlini L, Bertini E, Minetti C, Mongini T, Morandi L, Angelini C, et al. Motor function–muscle strength relationship in spinal muscular atrophy. Muscle Nerve. 2004;29(4):548–52.

Elsheikh B, Prior T, Zhang X, Miller R, Kolb SJ, Moore DAN, et al. An analysis of disease severity based on SMN2 copy number in adults with spinal muscular atrophy. Muscle Nerve. 2009;40(4):652–6. https://doi.org/10.1002/mus.21350.

Salazar R, Montes J, Dunaway Young S, McDermott MP, Martens W, Pasternak A, et al. Quantitative evaluation of lower extremity joint contractures in spinal muscular atrophy: implications for motor function. Pediatr Phys Ther. 2018;30(3):209–15. https://doi.org/10.1097/PEP.0000000000000515.

Fujak A, Kopschina C, Gras F, Forst R, Forst J. Contractures of the lower extremities in spinal muscular atrophy type II. Descriptive clinical study with retrospective data collection. Ortop Traumatol Rehabil. 2011;13(1):27–36.

Willig TN, Bach JR, Rouffet MJ, Krivickas LS, Maquet C. Correlation of flexion contractures with upper extremity function and pain for spinal muscular atrophy and congenital myopathy patients. Am J Phys Med Rehabil. 1995;74(1):33–8.

Willig TN, Paulus J, Lacau S, Guily J, Béon C, Navarro J. Swallowing problems in neuromuscular disorders. Arch Phys Med Rehabil. 1994;75(11):1175–81. https://doi.org/10.1016/0003-9993(94)90001-9.

Messina S, Pane M, De Rose P, Vasta I, Sorleti D, Aloysius A, et al. Feeding problems and malnutrition in spinal muscular atrophy type II. Neuromuscul Disord. 2008;18(5):389–93.

van Bruggen HW, Wadman RI, Bronkhorst EM, Leeuw M, Creugers N, Kalaykova SI, et al. Mandibular dysfunction as a reflection of bulbar involvement in SMA type 2 and 3. Neurology. 2016;86(6):552–9.

Sproule DM, Montes J, Dunaway S, Montgomery M, Battista V, Koenigsberger D, et al. Adiposity is increased among high-functioning, non-ambulatory patients with spinal muscular atrophy. Neuromuscul Disord. 2010;20(7):448–52.

Steffensen BF, Lyager S, Werge B, Rahbek J, Mattsson E. Physical capacity in non-ambulatory people with Duchenne muscular dystrophy or spinal muscular atrophy: a longitudinal study. Dev Med Child Neurol. 2002;44(9):623–32.

Ioos C, Leclair-Richard D, Mrad S, Barois A, Estournet-Mathiaud B. Respiratory capacity course in patients with infantile spinal muscular atrophy. Chest. 2004;126(3):831–7. https://doi.org/10.1378/chest.126.3.831.

LoMauro A, Romei M, Priori R, Laviola M, D'Angelo MG, Aliverti A. Alterations of thoraco-abdominal volumes and asynchronies in patients with spinal muscle atrophy type III. Respir Physiol Neurobiol. 2014;197:1–8. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.resp.2014.03.001.

Khirani S, Colella M, Caldarelli V, Aubertin G, Boule M, Forin V, et al. Longitudinal course of lung function and respiratory muscle strength in spinal muscular atrophy type 2 and 3. Eur J Paediatr Neurol. 2013;17(6):552–60. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ejpn.2013.04.004.

Sansone VA, Racca F, Ottonello G, Vianello A, Berardinelli A, Crescimanno G, et al. 1st Italian SMA family association consensus meeting: management and recommendations for respiratory involvement in spinal muscular atrophy (SMA) types I-III, Rome, Italy, 30-31 January 2015. Neuromuscul Disord. 2015;25(12):979–89. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.nmd.2015.09.009.

Rouault F, Christie-Brown V, Broekgaarden R, Gusset N, Henderson D, Marczuk P, et al. Disease impact on general well-being and therapeutic expectations of European type II and type III spinal muscular atrophy patients. Neuromuscul Disord. 2017;27(5):428–38. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.nmd.2017.01.018.

Dunaway S, Montes J, McDermott MP, Martens W, Neisen A, Glanzman AM, et al. Physical therapy services received by individuals with spinal muscular atrophy (SMA). J Pediatr Rehabil Med. 2016;9(1):35–44. https://doi.org/10.3233/prm-160360.

Cincotti F, Mattia D, Aloise F, Bufalari S, Schalk G, Oriolo G, et al. Non-invasive brain-computer interface system: towards its application as assistive technology. Brain Res Bull. 2008;75(6):796–803. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.brainresbull.2008.01.007.

Hasegawa Y, Oura S, Takahashi J. Exoskeletal meal assistance system (EMAS II) for patients with progressive muscular disease. Adv Robotics. 2013;27(18):1385–98. https://doi.org/10.1080/01691864.2013.841311.

Haumont T, Rahman T, Sample W, King MM, Church C, Henley J, et al. Wilmington robotic exoskeleton: a novel device to maintain arm improvement in muscular disease. J Pediatr Orthop. 2011;31(5):e44–e9. https://doi.org/10.1097/BPO.0b013e31821f50b5.

Kubota M, Sakakihara Y, Nagata T, Nitta H, Oka A, Horio K, et al. New ocular movement detector system as a communication tool in ventilator-assisted Werdnig-Hoffmann disease. Dev Med Child Neurol. 2000;42(1):61–4.

Fujak A, Kopschina C, Forst R, Mueller LA, Forst J. Use of orthoses and orthopaedic technical devices in proximal spinal muscular atrophy. Results of survey in 194 SMA patients. Disabil Rehabil Assist Technol. 2011;6(4):305–11.

Hunter M, Heatwole C, Luebbe E, Johnson NE. What matters Most: a perspective from adult spinal muscular atrophy patients. J Neuromuscul Dis. 2016;3(3):425–9.

Jeppesen J, Madsen A, Marquardt J, Rahbek J. Living and ageing with spinal muscular atrophy type 2: observations among an unexplored patient population. Dev Neurorehabil. 2010;13(1):10–8. https://doi.org/10.3109/17518420903154093.

Ho HM, Tseng YH, Hsin YM, Chou FH, Lin WT. Living with illness and self-transcendence: the lived experience of patients with spinal muscular atrophy. J Adv Nurs. 2016;72(11):2695–705. https://doi.org/10.1111/jan.13042.

Lamb C, Peden A. Understanding the experience of living with spinal muscular atrophy: a qualitative description. J Neurosci Nurs. 2008;40(4):250–6. https://doi.org/10.1097/01376517-200808000-00009.

Montes J, Garber CE, Kramer SS, Montgomery MJ, Dunaway S, Kamil-Rosenberg S, et al. Single-blind, randomized, controlled clinical trial of exercise in ambulatory spinal muscular atrophy: why are the results negative? J Neuromuscul Dis. 2015;2(4):463–70. https://doi.org/10.3233/jnd-150101.

Madsen KL, Hansen RS, Preisler N, Thøgersen F, Berthelsen MP, Vissing J. Training improves oxidative capacity, but not function, in spinal muscular atrophy type III. Muscle Nerve. 2015;52(2):240–4. https://doi.org/10.1002/mus.24527.

Bach JR, Wang TG. Noninvasive long-term ventilatory support for individuals with spinal muscular atrophy and functional bulbar musculature. Arch Phys Med Rehabil. 1995;76(3):213–7.

Ward K, Ford V, Ashcroft H, Parker R. Intermittent daytime mouthpiece ventilation successfully augments nocturnal non-invasive ventilation, controlling ventilatory failure and maintaining patient independence. BMJ Case Rep. 2015;2015. https://doi.org/10.1136/bcr-2015-209716.

Chalmers RM, Howard RS, Wiles CM, Hirsch NP, Miller DH, Williams A, et al. Respiratory insufficiency in neuronopathic and neuropathic disorders. QJM. 1996;89(6):469–76.

Katayama M, Naritomi H, Nishio H, Watanabe T, Teramoto S, Kanda F, et al. Long-term stabilization of respiratory conditions in patients with spinal muscular atrophy type 2 by continuous positive airway pressure: a report of two cases. Kobe J Med Sci. 2011;57(3):E98–105.

Wang TG, Bach JR, Avilla C, Alba AS, Yang GF. Survival of individuals with spinal muscular atrophy on ventilatory support. Am J Phys Med Rehabil. 1994;73(3):207–11.

Chen Y-S, Shih H-H, Chen T-H, Kuo C-H, Jong Y-J. Prevalence and risk factors for feeding and swallowing difficulties in spinal muscular atrophy types II and III. J Pediatr. 2012;160(3):447–51 e1.

Cha TH, Oh DW, Shim JH. Noninvasive treatment strategy for swallowing problems related to prolonged nonoral feeding in spinal muscular atrophy type II. Dysphagia. 2010;25(3):261–4. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00455-009-9269-1.

Kissel JT, Elsheikh B, King WM, Freimer M, Scott CB, Kolb SJ, et al. SMA valiant trial: a prospective, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial of valproic acid in ambulatory adults with spinal muscular atrophy. Muscle Nerve. 2014;49(2):187–92. https://doi.org/10.1002/mus.23904.

Saito T, Nurputra DK, Harahap NIF, Harahap ISK, Yamamoto H, Muneshige E, et al. A study of valproic acid for patients with spinal muscular atrophy. Neurol Clin Neurosci. 2015;3(2):49–57. https://doi.org/10.1111/ncn3.140.

Weihl CC, Connolly AM, Pestronk A. Valproate may improve strength and function in patients with type III/IV spinal muscle atrophy. Neurology. 2006;67(3):500–1. https://doi.org/10.1212/01.wnl.0000231139.26253.d0.

Merlini L, Solari A, Vita G, Bertini E, Minetti C, Mongini T, et al. Role of gabapentin in spinal muscular atrophy: results of a multicenter, randomized Italian study. J Child Neurol. 2003;18(8):537–41. https://doi.org/10.1177/08830738030180080501.

Miller RG, Moore DH, Dronsky V, Bradley W, Barohn R, Bryan W, et al. A placebo-controlled trial of gabapentin in spinal muscular atrophy. J Neurol Sci. 2001;191(1–2):127–31.

Chen TH, Chang JG, Yang YH, Mai HH, Liang WC, Wu YC, et al. Randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial of hydroxyurea in spinal muscular atrophy. Neurology. 2010;75(24):2190–7. https://doi.org/10.1212/WNL.0b013e3182020332.

Tiziano FD, Lomastro R, Abiusi E, Pasanisi MB, Di Pietro L, Fiori S, et al. Longitudinal evaluation of SMN levels as biomarker for spinal muscular atrophy: results of a phase IIb double-blind study of salbutamol. J Med Genet. 2019;56(5):293–300. https://doi.org/10.1136/jmedgenet-2018-105482.

Giovannetti AM, Pasanisi MB, Cerniauskaite M, Bussolino C, Leonardi M, Morandi L. Perceived efficacy of salbutamol by persons with spinal muscular atrophy: a mixed methods study. Muscle Nerve. 2016;54(5):843–9. https://doi.org/10.1002/mus.25102.

Walter MC, Wenninger S, Thiele S, Stauber J, Hiebeler M, Greckl E, et al. Safety and treatment effects of Nusinersen in longstanding adult 5q-SMA type 3 - a prospective observational study. J Neuromuscul Dis. 2019;6(4):453–65. https://doi.org/10.3233/jnd-190416.

Veerapandiyan A, Eichinger K, Guntrum D, Kwon J, Baker L, Collins E, et al. Nusinersen for older patients with spinal muscular atrophy: a real-world clinical setting experience. Muscle Nerve. 2020;61(2):222–6. https://doi.org/10.1002/mus.26769.

Stolte B, Totzeck A, Kizina K, Bolz S, Pietruck L, Monninghoff C, et al. Feasibility and safety of intrathecal treatment with nusinersen in adult patients with spinal muscular atrophy. Ther Adv Neurol Disord. 2018;11:1756286418803246. https://doi.org/10.1177/1756286418803246.

Jacobson JP, Cristiano BC, Hoss DR. Simple fluoroscopy-guided transforaminal lumbar puncture: safety and effectiveness of a coaxial curved-needle technique in patients with spinal muscular atrophy and complex spines. AJNR Am J Neuroradiol. 2020;41(1):183–8. https://doi.org/10.3174/ajnr.A6351.

Ko D, Blatt D, Karam C, Gupta K, Raslan AM. Lumbar laminotomy for the intrathecal administration of nusinersen for spinal muscular atrophy: technical note and outcomes. J Neurosurg Spine. 2019:1–5. https://doi.org/10.3171/2019.2.Spine181366.

Bortolani S, Stura G, Ventilii G, Vercelli L, Rolle E, Ricci F, et al. Intrathecal administration of nusinersen in adult and adolescent patients with spinal muscular atrophy and scoliosis: Transforaminal versus conventional approach. Neuromuscul Disord. 2019;29(10):742–6. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.nmd.2019.08.007.

Kizina K, Stolte B, Totzeck A, Bolz S, Fleischer M, Monninghoff C, et al. Clinical implication of dosimetry of computed tomography- and fluoroscopy-guided intrathecal therapy with nusinersen in adult patients with spinal muscular atrophy. Front Neurol. 2019;10:1166. https://doi.org/10.3389/fneur.2019.01166.

Wurster CD, Winter B, Wollinsky K, Ludolph AC, Uzelac Z, Witzel S, et al. Intrathecal administration of nusinersen in adolescent and adult SMA type 2 and 3 patients. J Neurol. 2018;266(1):183–94. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00415-018-9124-0.

Hiscock A, Kuhn I, Barclay S. Advance care discussions with young people affected by life-limiting neuromuscular diseases: a systematic literature review and narrative synthesis. Neuromuscul Disord. 2017;27(2):115–9.

Parker D, Maddocks I, Stern LM. The role of palliative care in advanced muscular dystrophy and spinal muscular atrophy. J Paediatr Child Health. 1999;35(3):245–50.

Bianco F, Pane M, D'Amico A, Messina S, Delogu AB, Soraru G, et al. Cardiac function in types II and III spinal muscular atrophy: should we change standards of care? Neuropediatrics. 2015;46(1):33–6. https://doi.org/10.1055/s-0034-1395348.

Palladino A, Passamano L, Taglia A, D'Ambrosio P, Scutifero M, Cecio MR, et al. Cardiac involvement in patients with spinal muscular atrophies. Acta Myol. 2011;30(3):175–8.

Awater C, Zerres K, Rudnik-Schoneborn S. Pregnancy course and outcome in women with hereditary neuromuscular disorders: comparison of obstetric risks in 178 patients. Eur J Obstet Gynecol Reprod Biol. 2012;162(2):153–9. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ejogrb.2012.02.020.

Coker A, Scott W, McCune G. Antenatal care and delivery of a patient with spinal muscular atrophy complicated with severe kyphoscsoliosis. J Obstet Gynaecol. 1997;17(2):154–5.

Yim R, Kirschner K, Murphy E, Parson J, Winslow C. Successful pregnancy in a patient with spinal muscular atrophy and severe kyphoscoliosis. Am J Phys Med Rehabil. 2003;82(3):222–5. https://doi.org/10.1097/01.PHM.0000046621.00871.30.

Rudnik-Schöneborn S, Zerres K, Ignatius J, Rietschel M. Pregnancy and spinal muscular atrophy. J Neurol. 1992;239(1):26–30. https://doi.org/10.1007/bf00839207.

Andries F, Wevers CWJ, Wintzen AR, Busch HFM, Höweler CJ, De Jager AEJ, et al. Vocational perspectives and neuromuscular disorders. Int J Rehabil Res. 1997;20(3):255–73.

Kruitwagen-Van Reenen ET, Wadman RI, Visser-Meily JM, van den Berg LH, Schroder C, van der Pol WL. Correlates of health related quality of life in adult patients with spinal muscular atrophy. Muscle Nerve. 2016;54(5):850–5. https://doi.org/10.1002/mus.25148.

Bergsma A, Janssen MMHP, Geurts ACH, Cup EHC, de Groot IJM. Different profiles of upper limb function in four types of neuromuscular disorders. Neuromuscul Disord. 2017;27(12):1115–22. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.nmd.2017.09.003.

Bienias K, Ścibek J, Cegielska J, Kochanowski J. Evaluation of activities of daily living in patients with slowly progressive neuromuscular diseases. Neurol Neurochir Pol. 2018;52(2):222–7. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.pjnns.2017.10.007.

Fischer MJ, Asselman FL, Kruitwagen-van Reenen ET, Verhoef M, Wadman RI, Visser-Meily JMA, et al. Psychological well-being in adults with spinal muscular atrophy: the contribution of participation and psychological needs. Disabil Rehabil. 2019:1–9. https://doi.org/10.1080/09638288.2018.1555864.

McGraw S, Qian Y, Henne J, Jarecki J, Hobby K, Yeh W-S. A qualitative study of perceptions of meaningful change in spinal muscular atrophy. BMC Neurol. 2017;17(1):68. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12883-017-0853-y.

Abresch RT, Carter GT, Jensen MP, Kilmer DD. Assessment of pain and health-related quality of life in slowly progressive neuromuscular disease. Am J Hosp Palliat Care. 2002;19(1):39–48. https://doi.org/10.1177/104990910201900109.

Kruitwagen-van Reenen ET, van der Pol L, Schroder C, Wadman RI, van den Berg LH, Visser-Meily JMA, et al. Social participation of adult patients with spinal muscular atrophy: frequency, restrictions, satisfaction and correlates. Muscle Nerve. 2018;58(6):805–11. https://doi.org/10.1002/mus.26201.

Gunther R, Wurster CD, Cordts I, Koch JC, Kamm C, Petzold D, et al. Patient-reported prevalence of non-motor symptoms is low in adult patients suffering from 5q spinal muscular atrophy. Front Neurol. 2019;10:1098. https://doi.org/10.3389/fneur.2019.01098.

Boardman FK, Young PJ, Griffiths FE. Impairment experiences, identity and attitudes towards genetic screening: the views of people with spinal muscular atrophy. J Genet Couns. 2018;27(1):69–84.

van Haastregt JCM, de Witte LP, Terpstra SJ, Diederiks JPM, van der Horst FGEM, de Geus CA. Membership of a patients' association and well-being a study into the relationship between membership of a patients' association, fellow-patient contact, information received, and psychosocial well-being of people with a neuromuscular disease. Patient Educ Couns. 1994;24(2):135–48. https://doi.org/10.1016/0738-3991(94)90007-8.

Dunaway Young S, Montes J, Kramer SS, Podwika B, Rao AK, De Vivo DC. Perceived fatigue in spinal muscular atrophy: a pilot study. J Neuromuscul Dis. 2018;6(1):109–17. https://doi.org/10.3233/jnd-180342.

Qian Y, McGraw S, Henne J, Jarecki J, Hobby K, Yeh W. Understanding the experiences and needs of individuals with spinal muscular atrophy and their parents: a qualitative study. BMC Neurol. 2015;15:217. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12883-015-0473-3.

Wan HWY, Carey KA, D'Silva A, Kasparian NA, Farrar MA. “Getting ready for the adult world”: how adults with spinal muscular atrophy perceive and experience healthcare, transition and well-being. Orphanet J Rare Dis. 2019;14(1):74. https://doi.org/10.1186/s13023-019-1052-2.

Boardman F. Experiential knowledge of disability, impairment and illness: the reproductive decisions of families genetically at risk. Health. 2014;18(5):476–92. https://doi.org/10.1177/1363459313507588.

Klug C, Schreiber-Katz O, Thiele S, Schorling E, Zowe J, Reilich P, et al. Disease burden of spinal muscular atrophy in Germany. Orphanet J Rare Dis. 2016;11(1):58.

Kariyawasam DST, D'Silva A, Lin C, Ryan MM, Farrar MA. Biomarkers and the development of a personalized medicine approach in spinal muscular atrophy. Front Neurol. 2019;10:898. https://doi.org/10.3389/fneur.2019.00898.

De Vivo DC, Bertini E, Swoboda KJ, Hwu WL, Crawford TO, Finkel RS, et al. Nusinersen initiated in infants during the presymptomatic stage of spinal muscular atrophy: interim efficacy and safety results from the phase 2 NURTURE study. Neuromuscul Disord. 2019;29(11):842–56. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.nmd.2019.09.007.

Bonati U, Holiga S, Hellbach N, Risterucci C, Bergauer T, Tang W, et al. Longitudinal characterization of biomarkers for spinal muscular atrophy. Ann Clin Transl Neurol. 2017;4(5):292–304. https://doi.org/10.1002/acn3.406.

Wurster CD, Steinacker P, Gunther R, Koch JC, Lingor P, Uzelac Z, et al. Neurofilament light chain in serum of adolescent and adult SMA patients under treatment with nusinersen. J Neurol. 2020;267(1):36–44. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00415-019-09547-y.

Wurster CD, Gunther R, Steinacker P, Dreyhaupt J, Wollinsky K, Uzelac Z, et al. Neurochemical markers in CSF of adolescent and adult SMA patients undergoing nusinersen treatment. Ther Adv Neurol Disord. 2019;12:1756286419846058. https://doi.org/10.1177/1756286419846058.

Totzeck A, Stolte B, Kizina K, Bolz S, Schlag M, Thimm A, et al. Neurofilament heavy chain and tau protein are not elevated in cerebrospinal fluid of adult patients with spinal muscular atrophy during loading with Nusinersen. Int J Mol Sci. 2019;20(21). https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms20215397.

Tiziano FD, Lomastro R, Di Pietro L, Pasanisi MB, Fiori S, Angelozzi C, et al. Clinical and molecular cross-sectional study of a cohort of adult type III spinal muscular atrophy patients: clues from a biomarker study. Eur J Hum Genet. 2013;21(6):630–6. https://doi.org/10.1038/ejhg.2012.233.

Farrar MA, Park SB, Vucic S, Carey KA, Turner BJ, Gillingwater TH, et al. Emerging therapies and challenges in spinal muscular atrophy. Ann Neurol. 2017;81(3):355–68. https://doi.org/10.1002/ana.24864.

Crowley R, Wolfe I, Lock K, McKee M. Improving the transition between paediatric and adult healthcare: a systematic review. Arch Dis Child. 2011;96(6):548. https://doi.org/10.1136/adc.2010.202473.

Acknowledgements

Not applicable.

Funding

A/Prof Farrar received grant support from the Motor Neurone Diseases Research Institute of Australia Beryl Bayley MND Postdoctoral Fellowship (152324). A/Prof Kasparian is the recipient of a National Heart Foundation of Australia Future Leader Fellowship (101229), and a 2018–2019 Harkness Fellowship in Health Care Policy and Practice from the Commonwealth Fund. Prof Vucic has received grant support from the National Health and Medical Research Council of Australia. Prof Kiernan has received grant support from the National Health and Medical Research Council of Australia.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

All authors contributed to study design and development of the search criteria. HW and KC performed the literature search. HW, KC, AD, MF critically reviewed the literature. HWYW prepared the first draft of the manuscript. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

Not applicable.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

MF has served on the scientific advisory board for Biogen. SV has received honoraria from Merck Serono Australia. MK is the Editor-in-Chief Journal of Neurology, Neurosurgery & Psychiatry (BMJ Publishing Group, UK); 2010-present. HW, AD, KC, NK report no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/. The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver (http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/) applies to the data made available in this article, unless otherwise stated in a credit line to the data.

About this article

Cite this article

Wan, H.W.Y., Carey, K.A., D’Silva, A. et al. Health, wellbeing and lived experiences of adults with SMA: a scoping systematic review. Orphanet J Rare Dis 15, 70 (2020). https://doi.org/10.1186/s13023-020-1339-3

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s13023-020-1339-3