Abstract

Background

A study was designed to identify the source of fever in a patient with post-polycythemia myelofibrosis, associated with clonal Janus Kinase 2 (JAK2) mutation involving duplication of exon 12. The patient presented with 1–2 day long self-limited periodic episodes of high fever that became more frequent as the hematologic disease progressed.

Methods

After ruling out other causes for recurrent fever, analysis of the pyrin encoding Mediterranean fever gene (MEFV) was carried out by Sanger sequencing in peripheral blood DNA samples obtained 4 years apart, in buccal cells, laser dissected kidney tubular cells, and FACS-sorted CD3-positive or depleted mononucleated blood cells. Hematopoeitc cells results were validated by targeted deep sequencing. A Sanger sequence based screen for pathogenic variants of the autoinflammatory genes NLRP3, TNFRSF1A and MVK was also performed.

Results

A rare, c.1955G>A, p.Arg652His MEFV gene variant was identified at negligible levels in an early peripheral blood DNA sample, but affected 46 % of the MEFV alleles and was restricted to JAK2-positive, polymorphonuclear and CD3-depleted mononunuclear DNA samples obtained 4 years later, when the patient experienced fever bouts. The patient was also heterozygous for the germ line, non-pathogenic NLRP3 gene variant, p.Q705K. Upon the administration of colchicine, the gold standard treatment for familial Mediterranean fever (FMF), the fever attacks subsided.

Conclusions

This is the first report of non-transmitted, acquired FMF, associated with a JAK2 driven clonal expansion of a somatic MEFV exon 10 mutation. The non-pathogenic germ line NLRP3 p.Q705K mutation possibly played a modifier role on the disease phenotype.

Similar content being viewed by others

Background

Polycythemia vera (PV; MIM 263330) is a clonal progressive myeloproliferative disorder primarily characterized by elevation in red blood cells, often with increased myeloid elements. The major pathogenic event in PV is the acquisition of a somatic gain-of-function mutation in the Janus Kinase 2 gene (JAK2; MIM 147796), resulting in erythropoietin independent proliferation of erythroid progenitor cells. Approximately 96 % of PV cases involve the p.V617F mutation in exon 14 of JAK2 [1], while 3 % involve exon 12, with 37 different mutations described to date [2–5]. Transformation into myelofibrosis and acute leukemia occurs in 10 and <3 % of the patients, respectively, during a 10-year disease course [1].

The Mediterranean fever gene (MEFV; MIM 608107) is highly expressed in myeloid cells, particularly in mature granulocytes. This gene codes for pyrin, a cytoplasmatic protein that regulates the maturation and secretion of the proinflammatory cytokines IL-1b and IL-18 in the inflammasome complex [6–9]. Missense mutations in MEFV associate with familial Mediterranean fever (FMF; MIM 249100), an autoinflammatory and inherited disorder prevalent in Mediterranean descendants. FMF is characterized by 2–3 days long self-limited attacks of fever, abdominal pain, arthritis and /or pleuritis [10]. The attacks are accompanied by leukocytosis and neutrophil infiltration to synovial membranes. Colchicine is the gold standard treatment for FMF, and is of diagnostic value. Biallelic MEFV exon 10 mutations are detected in 50–60 % of FMF patients. In 10–20 % of patients a monoallelic mutation is found, usually manifested with mild symptoms [11–15]. A gain-of-function, leading to an increase in the maturation of proinflammatory cytokines to their secreted forms, was suggested to explain the pathogenicity of these conservative missense MEFV mutations [8, 9]. A case of transmission of FMF by bone marrow transplantation from a donor with undiagnosed FMF proved the disease could be acquired through MEFV mutated hematopoietic cells [16].

Herein, we present for the first time genetic evidence for naturally acquired FMF, in a middle aged patient who had post-PV myelofibrosis. The patient developed FMF, while a negligible, myeloid restricted somatic MEFV exon 10 mutation increased in its mosaicism level. Co-segregation into myeloid cells with a JAK2 mutation with growth advantage suggests that the MEFV mutation was a hitchhiker during clonal expansion.

Methods

Patient

The patient is a 59 years old Ashkenazi Jewish female diagnosed with PV at 52 years, and followed at the Sheba Medical Center, Tel Hashomer, IL. Genetic testing for the JAK2 p.V617F mutation was negative but sequencing of exon 12 revealed the NM_004972.3:c.1608_1640dup variant, known as F537-I546dup+F546L on the protein level [3] and designated p.(Ile546_Phe547insLeuPheHisLysIleArgAsnGluAspLeuIle) according to HGVS nomenclature. This duplication predicts a substitution in the p.Phe547 hotspot residue followed by insertion of ten amino acids in the SH2 linker and pseudokinase JH2 domain. The patient has been treated with phlebotomies when needed and with100 mg acetylsalicylate daily. Four years later the patient’s spleen enlarged dramatically reaching 20 cm and a bone marrow biopsy confirmed transformation into myelofibrosis according to the international working group for myelofibrosis [17]. At that time, the patient developed fever bouts, initially reaching 38 °C and lasting 24 h, at 2 months intervals and a year after occurring at shorter intervals, rising to 39 °C and lasting up to 48 h with occasional abdominal pain and/or muscle aches. The C-reactive protein was elevated during fever, reaching 19 mg/L (normal levels <0.08–5 mg/L). Extensive work up for fever of unknown origin failed to detect infection, malignancy, collagen disease or thrombotic events. Clinical diagnosis of FMF was then considered. Surprisingly, a rare mutation in the MEFV gene was detected and daily treatments with 1 mg colchicine abated the fever. A recent development of mild renal failure with moderate proteinuria led us to perform a kidney biopsy.

Samples

Polymorphonuclear (PMC) and mononuclear cells (PBMC) were isolated by density gradient centrifugation using Histopaque 1077 (Sigma-Aldrich, St. Louis, MO), yielding a pellet of PMC and a PBMC cell band at the Histopaque/plasma interphase. Genomic DNA was prepared from whole and isolated fractions of peripheral blood cells (PBC), and from buccal cells using a commercially available kit (iNtRON biotechnology, Kyungki-Do, Korea). Genomic DNA from kidney tubule cells was purified with a column-based method (QIAamp® DNA Micro Kit; Qiagen). This study was approved by the ethics committee at the Sheba Medical Center, and was performed according to the declaration of Helsinki.

Genetic analyses

The JAK2 p.V617F mutation was excluded [18]. JAK2 exon 12 was PCR-amplified with flanking primers. Two distinct gel bands on a 2 % agarose gel were excised, purified by MinElute Gel extraction kit (QIAGEN, Hilden, Germany) and sequenced. Amplicons of MEFV exons 1–10 (LRG_190t1), NLRP3 exon 3 (LRG_197t1), TNFRSF1A exons 2–4 (LRG_193t1), and MVK exons 2–11 (LRG_156t1) were sequenced after Exo-Sap treatment. Sequencing reactions were performed using the Big Dye Terminator kit (Applied Biosystems, California, USA) on an ABI 3130XL automated sequencer, and the sequences were analyzed with BioEdit or blast software.

For targeted deep sequencing, a first PCR reaction surrounding the c.1955 nucleotide change of MEFV was performed in triplicate. Barcodes were incorporated to amplicons during a second, nested round of amplification. Amplicons were then purified using Agentcourt AMPureXP beads (Beckman coulter, Nyon, Switzerland) and the DNA quantified using High Sensitivity DNA kits for Bioanalyzer (Agilent technologies, Ca, USA). Sequencing and analyses were performed using the 400 bp kit on a PGM system, Ion Torrent server and Ion Reporter software, according to manufacturer’s instructions (Ion Torrent, Life Technologies, Guilford, Connecticut, USA). Coverage at the c.1955 position was at least ×3000.

Restriction Site Length Polymorphism (RFLP) analysis

Exon 10 RFLP of the c.1955G>A MEFV variant was performed with Fnu4hI enzyme (New England Biolabs, Ipswich, MA, USA) following manufacturer’s instructions.

FACS cell sorting

PBMC were immunostained with PE-conjugated anti-CD3 (UCHT1) mAbs from BD Biosciences (San Jose, CA) for 15 min at room temperature. Two cell populations, CD3+ T cells and CD3-depleted PBMC were sorted with high purity (>95 %) with a stringent multiparametric discrimination algorithm, by FACSAria digital cell sorter (BD Biosciences).

Pathology

Bone marrow biopsies obtained in 2009 and 2012 showed morphological features of myelofibrosis with increased reticulin fibers (grade 2). Kidney biopsy showed diffuse mesangioproliferative and focal endocapillary proliferative glomerulonephritis. Immunofluorescence showed IgM and C3+ granular stain without clonality. Congo red staining was negative for amyloid.

Laser capture microdissection

Five-micrometres thick paraffin embedded kidney biopsy sections were placed on membrane-coated slides (PALM, Munich, Germany), heated at 60 °C overnight and stained with hematoxillin and eosine. Tubular cells were dissected and catapulted onto a microfuge tube lid on a robotstage microscope equipped with a 337-nm pulsed laser microbeam (PALM, Munich, Germany) with a single laser shot.

Results

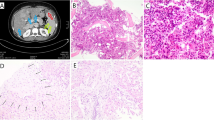

The patient presented with post-PV myelofibrosis involving a rare duplication in exon 12 of JAK2 (Fig. 1a) previously described in one patient [3]. The occurrence of recurrent fever in the absence of any known underlying cause led us to search for MEFV gene mutations. Her Ashkenazi origin, middle aged onset and lack of family history of FMF were not conflicting, as these have been previously noted [19, 20]. The NM_000243.2:c.1955G>A mutation (rs28940581) was found in exon 10 (Fig. 2a and 2g) predicting a p.Arg652His substitution in the PRYSPRY domain of pyrin. In the domain 3D model, the R652 residue localizes to the β5 strand end within sheet B. This variant was recently reported in a patient affected by Crohn’s disease [21], a well-established comorbidity with FMF [22]. A somatic origin for the p.Arg652His mutation was suggested to explain the post-PV MF associated recurrent fever. We therefore tested a DNA sample preceding the onset of fever by 4 years, when a search for a JAK2 mutation was performed. In the early sample the mutated MEFV variant was repeatedly observed at a negligible level by Sanger sequencing (Fig. 2b) whereas the JAK2 exon 12 extra gel band was highly visible. To further characterize the somatic origin of the MEFV mutation, we performed cell sorting on PBMC. Both the MEFV p.Arg652His and JAK2 exon 12 mutations were present in CD3-depleted peripheral blood mononuclear cells and the polymorphonuclear cells, but not in CD3+ T lymphocytes (Figs. 1b, 2c and d). Of note, JAK2 mutations are reported undetectable in T cells. Targeted deep sequencing confirmed these results showing a mutated MEFV allele frequency of 46 % in peripheral blood and in polymorphonuclear cells, 27 % in CD3-depleted PBMC and 0 % in CD3+ T cells. In the DNA of buccal cells neither the JAK2 nor the MEFV mutations were detected (Figs. 1c and 2e).

Sanger Sequencing results of JAK2 exon 12 DNA sequence (NM_004972.3). DNA sequencing a of PBC presenting the c.1608_1640dup nutation b-c of CD3+ cells and buccal cells presenting wild type DNA sequence of the gene. The rectangle contains the exon 12 sequence which is duplicated in the PBC sample and not in the CD3+ T cells or the buccal cells

Detection, expansion and somatic distribution of the MEFV c.1955G>A mutation demonstrated by Sanger sequencing. a PBC DNA sample of the patient from 2009 b an earlier sample from 2005 c CD3-positive T cells, d PMC enriched fraction, e buccal cells, f kidney tubule cells. g Fnu4h1 RFLP of MEFV exon 10 visualized on a 4 % agarose E-gel. The MEFV mutation abolishes the second of three restriction sites yielding a longer, 350 base pairs fragment. h Small power photomicrograph demonstrating a glomerulus and tubular cells. h-a High power photomicrograph demonstrating a desiccated tubule cell, h-b before and h-c after laser capture microdissection procedure (hematoxylin and eosin stain magnification ×400)

After the control of fever with colchicine treatment for almost a year, the patient developed heavy proteinuria with mild renal failure requiring kidney biopsy. We expected to detect glomerulosclerosis, a known late complication of myeloproliferative disorder (MPD) or secondary amyloid nephropathy related to FMF. Unexpectedly, the kidney biopsy showed membranoproliferative glomerulonephritis and Congo red staining was negative for amyloid. The somatic origin and restriction of the MEFV mutation to hematopoietic cells was then re-challenged and reaffirmed on single tubule cells derived from kidney biopsy (Fig. 2f and h). These results support the somatic nature of both JAK2 and MEFV mutations, their restriction to a myeloid clone and an increase in the somatic MEFV mutation burden associated with myelofibrosis progression.

Finally, sequencing of three other known autoinflammatory genes revealed one heterozygous, non-pathogenic variant in the NLRP3 gene, NM_004895.4:c.2113C>A, p.Gln705Lys (historically called Q703K). This variant was detected in both the early and late peripheral blood DNA samples as well as in CD3+ T cells, and was concluded to be a germ line mutation.

Discussion

The genetic analysis of a post-PV myelofibrotic patient clinically diagnosed with FMF [10] revealed a unique somatic MEFV variant which, in parallel to the development and aggravation of FMF attacks, underwent expansion. In addition, the patient had a known, prevalent germ line NLRP3 variant, unrelated to a specific autoinflammatory disease, yet reported to lead to an overactive NLRP3 inflammasome, or suggested to be a low penetrance variant, which hitherto was clinically silent [23, 24].

Several findings support a pathogenic role for the rare somatic MEFV mutation. First, the p.Arg652His variant was the sole variation in the coding region of the gene. Second, the somatic variant was confined to the disease effector cells, and third, the level of MEFV mosaicism increased in association to the development and progressive aggravation of the FMF attacks.

On the other hand, we argue against a pathogenic role for the germ line p.Q705K NLRP3 variant in the development of FMF, since the patient did not have an inflammatory phenotype prior to the expansion of the MEFV mutation, nor is this variant known to cause FMF. At most, it may have up-regulated the proinflammatory effect of the MEFV mutation, serving as a modifier gene in the myeloid cells [25].

Conceivably, the acquisition of a pathogenic mutation in the MEFV gene in somatic cells is more frequent than heretofore observed. It remains unnoticed however, when present in only a few cells. Somatic expansion of the MEFV mutation made the p.Arg652His mutation clinically visible in our patient, and tight co-segregation supports a JAK2 driven expansion of an MEFV mutated myeloid clone, irrespective of the order in which the two mutations occurred.

It is possible that the magnitude of inflammation was up-regulated in our patient by a combined effect of the rare exon 12 JAK2 mutation and the germ line, p.Q705K modifier variant, on the inflammasome priming via the ERK tract [2, 25]. It may also be that in other instances recurrent FMF fever bouts have been misclassified as constitutional symptoms, related to the primary disease.

Myeloid restricted, non-malignant somatic mosaicism with low and variable degree (8–27 %) has recently been reported in the NLRP3 gene of patients with the autoinflammatory, variant type Schnitzler syndrome, an urticarial and systemic inflammation disease with monoclonal gammopathy [26], and in a case of cyropyrin associated periodic syndrome (CAPS) [27]. NLRP3 mosaicism affecting several tissue types is more frequently found, especially in NOMID/CINCA patients who test negative for a heterozygous germ line mutation [28, 29]. Lastly, a case of somatic mosaicism has been reported in a patient with Blau syndrome [30]. To the best of our knowledge the present case is the first demonstration of a somatic MEFV mutation, expanding the spectrum of autoinflammaory diseases caused by somatic mosacism.

In summary, this paper highlights a diversion of nature in the course of post-PV myelofibrosis. For such a diversion to occur two concomitant events are necessary: A proliferation driver mutation should evolve in myeloid cells and a passenger pathogenic mutation should occur in a gene which is normally expressed in the proliferating clone. Whether the driver and the hitchhiker mutations converged in our case to regulate a common pathogenic pathway awaits further proof. The phenomenon described herein may also elucidate the pathogenesis of recurrent fever of unknown origin frequently detected in other malignancies.

Conclusions

This work provides clinical and genetic evidence for a unique pathogenic route that leads to acquired FMF. A somatic, myeloid restricted mutation in the Mediterranean fever gene of a patient with post-PV myelofibrosis expanded from negligible to 46 % of total MEFV alleles in peripheral blood cells, parallel to the development of colchicine responsive inflammatory fever bouts. Co-segregation of the MEFV and JAK2 exon 12 mutations into myeloid cells suggests the MEFV mutation was a passenger in a JAK2 driven proliferating clone. Other autoinflammatory diseases may be acquired due to somatic mutations in additional clonal myeloproliferative diseases.

References

Tefferi A. Polycythemia vera and essential thrombocythemia: 2013 update on diagnosis, risk, stratification, and management. Am J Hematol. 2013;88:964–72.

Scott LM, Tong W, Levine RL, Scott MA, Beer PA, Stratton MR, et al. JAK2 exon 12 mutations in polycythemia vera and idiopathic erythrocytosis. N Engl J Med. 2007;356:459–68.

Pietra D, Li S, Brisci A, Passamonti F, Rumi E, Theocharides A, et al. Somatic mutations of JAK2 exon 12 in patients with JAK2 (V617F)-negative myeloproliferative disorders. Blood. 2008;111:1686–9.

Schnittger S, Bacher U, Haferlach C, Geer T, Müller P, Mittermüller J, et al. Detection of JAK2 exon 12 mutations in 15 patients with JAK2V617F negative polycythemia vera. Haematologica. 2009;94:414–8.

Passamonti F, Elena C, Schnittger S, Skoda RC, Green AR, Girodon F, et al. Molecular and clinical features of the myeloproliferative neoplasm associated with JAK2 exon 12 mutations. Blood. 2011;117:2813–6.

Centola M, Wood G, Frucht DM, Galon J, Aringer M, Farrell C, et al. The gene for familial Mediterranean fever, MEFV is expressed in early leukocyte development and is regulated in response to inflammatory mediators. Blood. 2000;95:3223–31.

Tidow N, Chen X, Müller C, Kawano S, Gombart AF, Fischel-Ghodsian N, et al. Hematopoietic-specific expression of MEFV, the gene mutated in familial Mediterranean fever, and subcellular localization of its corresponding protein, pyrin. Blood. 2000;95:1451–5.

Chae JJ, Cho YH, Lee GS, Cheng J, Liu PP, Feigenbaum L, et al. Gain-of-function Pyrin mutations induce NLRP3 protein-independent interleukin-1β activation and severe autoinflammation in mice. Immunity. 2011;34:755–68.

Yang JL, Xu H, Shao F. Immunological function of familial Mediterranean fever disease protein Pyrin. Sci China Life Sci. 2014;57:1156–61.

Livneh A, Langevitz P, Zemer D, Zaks N, Kees S, Lidar T, et al. Criteria for the diagnosis of familial Mediterranean fever. Arthritis Rheum. 1997;40:1879–85.

Booty MG, Chae JJ, Masters SL, Remmers EF, Barham B, Le JM, et al. Familial Mediterranean fever with a single MEFV mutation: where is the second hit? Arthritis Rheum. 2009;60:1851–61.

Marek-Yagel D, Berkun Y, Padeh S, Abu A, Reznik-Wolf H, Livneh A, et al. Clinical disease among patients heterozygous for familial Mediterranean fever. Arthritis Rheum. 2009;60:1862–6.

Padeh S, Shinar Y, Pras E, Zemer D, Langevitz P, Pras M, et al. Clinical and diagnostic value of genetic testing in 216 Israeli children with Familial Mediterranean fever. J Rheumatol. 2003;30:185–90.

Hentgen V, Grateau G, Stankovic-Stojanovic K, Amselem S, Jéru I. Familial Mediterranean fever in heterozygotes: are we able to accurately diagnose the disease in very young children? Arthritis Rheum. 2013;65:1654–62.

Moradian MM, Sarkisian T, Ajrapetyan H, Avanesian N. Genotype-phenotype studies in a large cohort of Armenian patients with familial Mediterranean fever suggest clinical disease with heterozygous MEFV mutations. J Hum Genet. 2010;55:389–93.

Touitou I, Dumont B, Pourtein M, Perelman S, Sirvent A, Soler C. Transmission of familial Mediterranean fever mutations following bone marrow transplantation. Clin Genet. 2007;72:162–3.

Mesa RA, Verstovsek S, Cervantes F, Barosi G, Reilly JT, Dupriez B, et al. International Working Group for Myelofibrosis Research and Treatment (IWG-MRT) International Working Group for Myelofibrosis Research and Treatment (IWG-MRT). Primary myelofibrosis (PMF), post polycythemia vera myelofibrosis (post-PV MF), post essential thrombocythemia myelofibrosis (post-ET MF), blast phase PMF (PMF-BP): Consensus on terminology by the international working group for myelofibrosis research and treatment (IWG-MRT). Leukemia Res. 2007;31:737–40.

Passamonti F, Rumi E, Pietra D, Della Porta MG, Boveri E, Pascutto C, et al. Relation between JAK2 (V617F) mutation status, granulocyte activation, and constitutive mobilization of CD34+ cells into peripheral blood in myeloproliferative disorders. Blood. 2006;107:3676–82.

Lidar M, Kedem R, Berkun Y, Langevitz P, Livneh A. Familial Mediterranean fever in Ashkenazi Jews: the mild end of the clinical spectrum. J Rheumatol. 2010;37:422–5.

Tamir N, Langevitz P, Zemer D, Pras E, Shinar Y, Padeh S, et al. Late-onset familial Mediterranean fever (FMF): a subset with distinct clinical, demographic, and molecular genetic characteristics. Am J Med Genet. 1999;87:30–5.

Villani AC, Lemire M, Louis E, Silverberg MS, Collette C, Fortin G, et al. Genetic variation in the familial Mediterranean fever gene (MEFV) and risk for Crohn’s disease and ulcerative colitis. PLoS One. 2009;4:e7154.

Fidder HH, Chowers Y, Lidar M, Sternberg M, Langevitz P, Livneh A. Crohn disease in patients with familial Mediterranean fever. Medicine (Baltimore). 2002;81:411–6.

Verma D, Särndahl E, Andersson H, Eriksson P, Fredrikson M, Jönsson JI, et al. The Q705K polymorphism in NLRP3 is a gain-of-function alteration leading to excessive interleukin-1β and IL-18 production. PLoS One. 2012;7:e34977. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0034977.

Rieber N, Gavrilov A, Hofer L, Singh A, Öz H, Endres T, et al. A functional inflammasome activation assay differentiates patients with pathogenic NLRP3 mutations and symptomatic patients with low penetrance variants. Clin Immunol. 2015;157:56–64.

Ghonime MG, Shamaa OR, Das S, Eldomany RA, Fernandes-Alnemri T, Alnemri ES, et al. Priming by ipopolysaccharides dependent upon ERK signaling and proteasome function. J Immunol. 2014;192:3881–8.

de Koning HD, van Gijn ME, Stoffels M, Jongekrijg J, Zeeuwen PL, Elferink MG, et al. Myeloid lineage-restricted somatic mosaicism of NLRP3 mutations in patients with variant Schnitzler syndrome. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2015;135:561–4.

Zhou Q, Aksentijevich I, Wood GM, Walts AD, Hoffmann P, Remmers EF, et al. Cryopyrin-associated periodic syndrome caused by a myeloid-restricted somatic NLRP3 mutation. Arthritis Rheumatol. 2015. doi:10.1002/art.39190.

Arostegui JI, Lopez Saldana MD, Pascal M, Clemente D, Aymerich M, Balaguer F, et al. A somatic NLRP3 mutation as a cause of a sporadic case of chronic infantile neurologic, cutaneous, articular syndrome/neonatal-onset multisystem inflammatory disease: novel evidence of the role of low-level mosaicism as the pathophysiologic mechanism underlying mendelian inherited diseases. Arthritis Rheum. 2010;62(4):1158–66.

Tanaka N, Izawa K, Saito MK, Sakuma M, Oshima K, Ohara O, et al. High incidence of NLRP3 somatic mosaicism in patients with chronic infantile neurologic, cutaneous, articular syndrome: results of an International Multicenter Collaborative Study. Arthritis Rheum. 2011;63(11):3625–32.

de Inocencio J, Mensa-Vilaro A, Tejada-Palacios P, Enriquez-Merayo E, Gonzalez-Roca E, Magri G, et al. Somatic NOD2 mosaicism in Blau syndrome. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2015. doi:10.1016/j.jaci.2014.12.1941.

Acknowledgement

We would like to thank Hilla Tabiban Keissar, Anna Goreshnik for technical assistance.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Authors’ contributions

YS, TT, and OS designed and performed the research, analyzed the data and wrote the manuscript. GR, NA and AL designed the research and contributed to the scientific discussion. GS contributed to research design, data acquisition, analysis and discussion. MN, RC, AH, EG-R, JIA and IG contributed to data acquisition and analysis. OK, and YS analyzed and evaluated the patient. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Yael Shinar and Tali Tohami contributed equally to this work.

Rights and permissions

This article is published under an open access license. Please check the 'Copyright Information' section either on this page or in the PDF for details of this license and what re-use is permitted. If your intended use exceeds what is permitted by the license or if you are unable to locate the licence and re-use information, please contact the Rights and Permissions team.

About this article

Cite this article

Shinar, Y., Tohami, T., Livneh, A. et al. Acquired familial Mediterranean fever associated with a somatic MEFV mutation in a patient with JAK2 associated post-polycythemia myelofibrosis. Orphanet J Rare Dis 10, 86 (2015). https://doi.org/10.1186/s13023-015-0298-6

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s13023-015-0298-6