Abstract

Objectives

Acute compartment syndrome (ACS) can be caused by multiple causes that affect people of different ages. It is considered an orthopedic emergency condition that requires immediate diagnosis and surgical intervention to avoid devastating complications and irreversible damages. This systematic review aimed to present the etiology of trauma-related forearm ACS.

Methods

A systematic review was performed on four different databases: Embase, Medline, Cochrane Central Register of Controlled Trials (CENTRAL) and Cochrane Database of systematic review register databases via Ovid, with no restriction on dates (last date was June 30, 2021). It included all the studies containing data about the etiology of trauma-related forearm ACS.

Results

A total of 4893 articles were retrieved: 122 met the inclusion criteria, 39 were excluded, 25 were out of scope and 14 had insufficient details. Hence, this review constituted 83 articles and 684 patients. The etiology of ACS causing forearm ACS was classified into three groups: fracture-related, soft tissue injury-related and vascular injury-related. The fracture-related group was the most common group (65.4%), followed by soft tissue injury (30.7%), then vascular injuries (3.9%). Furthermore, supracondylar humerus fractures were the most common cause of fractures related to forearm ACS. Blunt traumas were the most common cause of soft tissue injuries-related forearm ACS, and brachial artery injuries were the most common cause of vascular-related forearm ACS.

Conclusion

Frequent assessment of patients with the most prevalent etiologies of forearm ACS is recommended for early detection of forearm ACS and to save limbs.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Acute compartment syndrome (ACS) of the forearm is defined as increased pressure in the closed osteofascial compartment of the forearm with a compromised microcirculation leading to ischemia and tissue damage [1]. The myofascial compartments of the upper extremity are divided into the shoulder and arm, the forearm and the hand based on the anatomic region [2]. Forearm is the most common site for ACS in the upper extremity and the second most common site for ACS in the body after the leg [3]. The diagnosis of ACS is mainly clinical, with pain that is disproportionate to the size of injury, being a known hallmark component of the clinical presentation. However, the patient may not exhibit clinical signs, which makes this a challenging task for the on-call trauma surgeon to diagnose and eventually increase the risk of late or misdiagnosis of this pathology [4, 5]. Thus, a high index of clinical suspicion is needed when treating ACS. A delay in the treatment could lead to complications including neurological deficits, fracture nonunion, muscle necrosis, chronic pain, and forearm contractures [6,7,8,9].

To our knowledge, there have been no previous systematic reviews that have focused on the possible etiologies of acute trauma-related forearm compartment syndrome, except for the Kalyani et al. [6] study in 2011. They have discussed both traumatic and non-traumatic etiologies of ACS. In addition, various studies have been presented to the literature since then, which contain additional information about the etiologies of ACS. Finally, understanding the causes of this devastating condition allows us to categorize the risk by identifying the group of high-risk patients, and the most common traumatic etiologies associated with them, leading to early diagnosis and intervention, fewer complications and overall better outcome.

Therefore, the aim of this systematic review was to identify the most prevalent etiologies in the literature regarding acute trauma-related compartment syndrome of the forearm.

Materials and methods

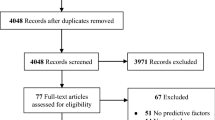

This systematic review was conducted and reported in light of the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analysis (PRISMA) checklist (Fig. 1).

Eligibility criteria

The inclusion criteria were studies containing data about the etiology of trauma-related forearm ACS, with available full text. The exclusion criteria were animal studies and non-English studies.

Search strategy

The Embase, Medline, Cochrane Central Register of Controlled Trials (CENTRAL) and Cochrane Database of systematic review register databases via Ovid were searched with no date restrictions, using the keywords: compartment syndrome AND forearm OR vascular OR trauma OR radius fracture OR forearm fracture OR ulna fracture OR humeral supracondylar fracture. The last date of the systematic search was on June 30, 2021. A search through the reference lists of the included studies was carried out for any potentially missed articles that fit the study criteria.

Study selection and extraction of data

Six authors carried out the eligibility screening of the titles and abstracts followed by full-text assessment, and data extraction from eligible articles was carried out. Finally, any disagreements were settled via discussions or decisions of a third author.

Results

A total of 4893 articles were retrieved, but only 122 met the inclusion criteria. Thirty-nine reports were excluded, 25 of them were out of scope and 14 articles had insufficient details. Thus, 83 articles with 684 patients [7, 10,11,12,13,14,15,16,17,18,19,20,21,22,23,24,25,26,27,28,29,30,31,32,33,34,35,36,37,38,39,40,41,42,43,44,45,46,47,48,49,50,51,52,53,54,55,56,57,58,59,60,61,62,63,64,65,66,67,68,69,70,71,72,73,74,75,76,77,78,79,80,81,82,83,84,85,86,87,88,89,90,91] constituted the basis of this review.

The etiology of the forearm ACS was classified into three groups according to the affected anatomical structure that caused the compartment syndrome: fracture-related, soft tissue injury-related and vascular injury-related causes.

Fracture-related ACS

Fifty-one articles provided relevant data about 447 fractured patients who developed an ACS (65.4%) [7, 10,11,12,13,14,15,16,17,18,19,20,21,22,23,24,25,26,27,28,29,30,31,32,33,34,35,36,37,38,39,40,41,42,43,44,45,46,47,48,49,50,51,52,53,54,55,56,57,58,59]. Eleven articles identified supracondylar humerus fracture (SCF) as the most prevalent site of fracture leading up to 152 cases (34% of SCF patients) of fractured patients causing ACS [7, 10, 11, 14, 15, 19, 22, 26, 52, 57, 58]; 19 articles reported both-bone forearm fractures making up to 123 cases (27.5%) of fractured patients [10, 16, 17, 20, 26, 29, 33, 34, 40, 44, 45, 50,51,52,53, 55, 56, 58]. Twenty articles reported distal radial fractures leading to ACS in 99 cases (22.1%) of fractured patients (Table 1) [10, 12, 18, 24, 26, 29, 30, 32, 39, 41, 43, 46,47,48,49, 51,52,53, 58].

Soft tissue injury-related ACS

Thirty-seven articles observed 210 patients who developed ACS (30.7%) after a soft tissue injury [7, 50,51,52,53,54,55,56,57,58, 60,61,62,63,64,65,66,67,68,69,70,71,72,73,74,75,76,77,78,79,80,81,82,83,84,85,86]. Four articles identified blunt trauma in 44 patients as the most prevalent cause of soft tissue trauma-related ACS, leading up to 20.9% of soft tissue-injured patients [57, 82, 85, 86]. Three identified 39 patients with burns (18.6%) [61, 76, 85], and six reported 36 patients with ACS (17.1%) that occurred after crush injury [65, 73, 74, 80, 85, 86]. Two did not specify the extent of the trauma, reporting generic soft tissue injuries in 37 patients as the cause of ACS (Table 2) [51, 53].

Vascular injury-related ACS

Eight articles related ACS to vascular injuries in 27 patients (3.9%) [59, 85,86,87,88,89,90,91]. Two articles [86, 91] reported seven patients who developed ACS after brachial artery injuries in 25.9% of ACS cases secondary to vascular injury. Two reported two patients, each with ACS, developed after ulnar artery injury [59, 88], and three reported 13 cases of forearm ACS developed after unspecified vascular injuries (Table 3) [85, 89, 90].

Within the 13 articles [7, 50,51,52,53,54,55,56,57,58,59, 85, 86] that were suitable to be included in two of the three groups, ten [7, 50,51,52,53,54,55,56,57,58] were included in fracture-related and soft tissue injury-related groups. In addition, one [59] was included in fracture-related and vascular injury-related groups, while the other two [85, 86] were included in vascular-related and soft tissue-related groups.

Discussion

In the current systemic review, the etiologies of traumatic forearm compartment syndrome were evaluated, revealing that fractures were the most common etiology leading to forearm ACS, in particular supracondylar humerus fractures. In addition, soft tissue injuries (blunt trauma) following fractures showed higher rates of forearm ACS than any other soft tissue injuries. Finally, vascular injuries were the least to cause forearm ACS.

Furthermore, fractures were the most common etiology of forearm ACS (65.3%), revealing that supracondylar humerus fractures were the most prevalent sites of fractures, occurring in 34% of fracture cases causing ACS, followed by both-bone forearm fractures (27.5%), followed by distal radius fractures (22.1%). Though supracondylar fractures were the most prevalent fracture causing forearm ACS, this should be looked at in view of Robertson et al. [15] study that described an incidence of 0.2% of ACS in supracondylar humeral fractures (67 cases of ACS out of 31,234 supracondylar fracture cases). This shows that supracondylar fractures are a common cause of forearm ACS, but ACS is not that common in supracondylar fractures. In addition, supracondylar humerus fractures were the most prevalent in the current review, which could be attributable to the vast pediatric population in this study. In line with the results, fractures were also the most common cause leading to 70% of ACS cases in Stella et al.’s systemic review of 95 articles on leg ACS [4].

When comparing the results of this study (83 articles) to that of Kalyani et al. [6] (12 articles), fractures were the leading cause of ACS and supracondylar fractures were the predominant cause out of these fractures, whereas their findings revealed that fractures were the second most common cause (after soft tissue injuries with a 2% difference) of ACS, consisting of 31%. The distal radius fracture was the most common site of fracture, occurring in 14.3% of their fracture cases (32 cases). However, in Oliver et al. [92] systemic review of the outcomes of forearm fasciotomies, they included 142 forearm ACS cases, but unfortunately, the etiologies were not mentioned.

Results also reveal that ACS injuries relating to the radius were more common in the distal part of the bone or concurrent injuries involving the radius with another bone [16, 33, 52, 53]. Duckworth et al.’s [51] findings of their study of 90 patients revealed that 31 (34%) distal radius fracture cases and 27 (30%) both-bone forearm fracture cases constituted 64% of the ACS cases, which is in line with the findings of the study in hand. Moreover, in 2009, Hwang et al. [29] (1286 patients) concluded that a fifty times higher risk was found in patients with combined distal radius fracture and elbow injury than patients with only distal radius fractures.

Another finding to consider is that the second most common cause of forearm ACS is soft tissue injury: Increased pressure within the compartment is associated with any injury to the surroundings or inside the compartment leading to ACS [53]. This injury can be secondary to either minor or major injuries, which have been observed to be blunt trauma in this study. Similarly, Stella et al. reported that soft tissue injuries were the second most common cause of leg ACS [4], and crush injuries were the most common cause of soft tissue injuries-related ACS.

Moreover, Kalyani et al.[6] (80 cases) reported a prevalence of 33.3% forearm ACS due to soft tissue injury, making it the most common cause of ACS. The differences between this study and theirs could be attributed to the fact that our study only focused on traumatic etiologies. In contrast, their study included all possible etiologies of forearm ACS regardless they were traumatic or not. Furthermore, Zhang et al. [85] study of 130 patients who underwent forearm fasciotomies 66% (86 patients) resulted from soft tissue injuries. Meanwhile, Özkan et al. [61] reported 43 fasciotomies in their study of 35 patients (81%) who had forearm ACS due to soft tissue injuries, indicating that even minimal injuries to soft tissues could lead to compartment syndrome. Thus, it is important not to underestimate any injuries, as forearm ACS was noticed to be caused by snakes, insects and spider bites [6, 60, 63, 64, 68, 81].

Results also revealed that forearm vascular-related ACS was mainly associated with trauma that could penetrate the skin and cause damage to the underlying vessels. Brachial artery was the most frequently affected artery causing ACS. Also, an increased pressure within a confined compartment by bleeding and local edema was the mechanism by which arterial injuries lead to ACS. Morin et al. [59] (2009) reported 3.8% cases of forearm ACS (5 out of 129) that were attributed to vascular trauma secondary to penetrating trauma. Similarly, Lagerstrom et al. [91] reported 32 cases of ACS, where 9 were in the forearm and 5 (15.6%) were due to brachial artery injury. Furthermore, Kalyani et al. [6] reported cases of forearm ACS (10.7%) that were attributed to vascular injuries.

The age range of each etiology was 3–75 years for fracture-related ACS, 7 days–68 years for soft tissue-related ACS, and newborns–33 years for vascular-related ACS.

Numerous complications can arise as a consequence of forearm ACS, including but not limited to nerve damage, gangrene, Volkmann’s contracture and rhabdomyolysis. These complications can affect the patient’s life greatly [93]. Therefore, the findings of this review help raise the suspicion around the traumatic etiologies of forearm ACS and guides the on-call trauma surgeon in decision-making, early diagnosis and avoiding the dreadful outcomes of this condition.

The strength of this review is the diversity and number of cases, which gave it a better estimate of the general population, although one of the limitations of this review was the incomplete information in many of the articles reviewed. In addition, 45 studies (53.6%) were case reports and retrospective case series, 32 (38.1%) level IV evidence, and several studies were conducted before 20 years or more. Thus, the need for more studies discussing the etiology of forearm ACS in a multicenter and prospective setting is recommended. We also acknowledge that this review was limited to studies written in English.

Conclusion

Forearm ACS can be caused by multiple etiologies that affect people of different ages. Therefore, identifying the most prevalent causes can help in early detection of ACS by frequent assessment of patients that present with the most prevalent causes like supracondylar humerus fractures among fractures and blunt trauma among soft tissue injuries.

Availability of data and materials

Data and materials are available upon request.

Patient's consent

Patient’s consent was not required as there were no patients in this study.

References

Chandraprakasam T, Kumar RA. Acute compartment syndrome of forearm and hand. Indian J Plast Surg. 2011;44(2):212–8.

Leversedge FJ, Moore TJ, Peterson BC, Seiler JG. Compartment syndrome of the upper extremity. J Hand Surg. 2011;36(3):544–59. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jhsa.2010.12.008.

Raza H, Mahapatra A. Acute compartment syndrome in orthopedics: causes, diagnosis, and management. Adv Orthop. 2015;19:2015.

Stella M, Santolini E, Sanguineti F, Felli L, Vicenti G, Bizzoca D, et al. Aetiology of trauma-related acute compartment syndrome of the leg: a systematic review. Injury. 2019;50(Suppl 2):S57-64.

Gourgiotis S, Villias C, Germanos S, Foukas A, Ridolfini MP. Acute limb compartment syndrome: a review. J Surg Educ. 2007;64(3):178–86.

Kalyani BS, Fisher BE, Roberts CS, Giannoudis PV. Compartment syndrome of the forearm: a systematic review. J Hand Surg Am. 2011;36(3):535–43.

Eaton RG, Green WT. Volkmann??s Ischemia: a volar compartment syndrome of the forearm. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 1975;113:58–64. https://doi.org/10.1097/00003086-197511000-00009.

McQueen MM. Acute compartment syndrome. In: Bucholz RW, Court-Brown CM, Heckman JD, Tornetta P, editors. Rockwood and Green’s fractures in adults. 7th ed. Philadelphia, PA: Lippincott Williams & Wilkins; 2010. p. 689–709.

Hope MJ, McQueen MM. Acute compartment syndrome in the absence of fracture. J Orthop Trauma. 2004;18:220–4.

Jerome TJ. Acute upper limb compartment syndrome in children: special focus on nerve recovery. World J Ped Surgery. 2020;3(3):e000158.

Kopriva J, Awowale J, Whiting P, Livermore A, Siy A, Hetzel S, et al. Compartment syndrome in operatively managed pediatric monteggia fractures and equivalents. J Pediatr Orthop. 2020;40(8):387–95.

Lee JH, Lee J-K, Park JS, Kim DH, Baek JH, Kim YJ, et al. Complications associated with volar locking plate fixation for distal radius fractures in 1955 cases: a multicentre retrospective study. Int Orthop. 2020;44(10):2057–67.

Anshuman R, Aggarwal AN, Pandey R, Mishra P, Yeptho P, Raj R. Type III Monteggia equivalent injury with compartment syndrome in an 8-year-old child: a case report. J Clin Orthop Trauma. 2019;10(4):800–3.

Harris LR, Arkader A, Broom A, Flynn J, Yellin J, Whitlock P, et al. Pulseless supracondylar humerus fracture with anterior interosseous nerve or median nerve injury, an absolute indication for open reduction? J Pediatr Orthop. 2019;39(1):e1–7.

Robertson AK, Snow E, Browne TS, Brownell ST, Inneh I, Hill JF. Who Gets Compartment Syndrome?: a retrospective analysis of the national and local incidence of compartment syndrome in patients with supracondylar humerus fractures. J Pediatr Orthop. 2018;38(5):e252–6.

Zuchelli D, Divaris N, McCormack JE, Huang EC, Chaudhary ND, Vosswinkel JA, et al. Extremity compartment syndrome following blunt trauma: a level I trauma center’s 5-year experience. J Surg Res. 2017;217:131–6.

Sato K, Suzuki T, Inaba N. Acute compartment syndrome in the forearm with trans-ulnar single incision. J Hand Surg Asian Pac. 2016;21(1):99–102.

Ganeshan RM, Mamoowala N, Ward M, Sochart D. Acute compartment syndrome risk in fracture fixation with regional blocks. BMJ Case Rep. 2015;26:2015.

Hill JF. The Incidence of Compartment Syndrome in Patients with Supracondylar Humerus Fractures. In 2015 AAP National Conference and Exhibition October 25, 2015. American Academy of Pediatrics. Washington, DC; 2015.

Blackman AJ, Wall LB, Keeler KA, Schoenecker PL, Luhmann SJ, O’Donnell JC, et al. Acute compartment syndrome after intramedullary nailing of isolated radius and ulna fractures in children. J Pediatr Orthop. 2014;34(1):50–4.

Elsaftawy A, Jablecki J. Acute compartment syndrome after open forearm fracture–scale of the problem and case report. Pol Przegl Chir. 2014;86(1):44–7.

Lightdale-Miric N, Kay R, Lee C, Chang E. Silent compartment syndrome in children: A report of five cases. J Pediatr Orthop B. 2014;23(5):467–71.

Martus JE, Preston RK, Schoenecker JG, Lovejoy SA, Green NE, Mencio GA. Complications and outcomes of diaphyseal forearm fracture intramedullary nailing: a comparison of pediatric and adolescent age groups. J Pediatr Orthop. 2013;33(6):598–607.

Esenwein P, Sonderegger J, Gruenert J, Ellenrieder B, Tawfik J, Jakubietz M. Complications following palmar plate fixation of distal radius fractures: a review of 665 cases. Arch Orthop Trauma Surg. 2013;133(8):1155–62.

Seigerman DA, Choi D, Donegan DJ, Yoon RS, Liporace FA. Upper extremity compartment syndrome after minor trauma: An imperative for increased vigilance for a rare, but limb-threatening complication. Patient Saf Surg. 2013;7(1):5.

Kanj WW, Gunderson MA, Carrigan RB, Sankar WN. Acute compartment syndrome of the upper extremity in children: diagnosis, management, and outcomes. J Pediatr Orthop. 2013;7(3):225–33.

Zehnder SW, Puryear AS. Forearm compartment syndrome secondary to an olecranon fracture. Curr Orthop Pract. 2010;21(3):327–9.

Flynn JM, Jones KJ, Garner MR, Goebel J. Eleven years experience in the operative management of pediatric forearm fractures. J Pediatr Orthop. 2010;30(4):313–9.

Hwang RW, de Witte PB, Ring D. Compartment syndrome associated with distal radial fracture and ipsilateral elbow injury. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2009;91(3):642–5.

Chloros GD, Papadonikolakis A, Ginn S, Wiesler ER. Pronator quadratus space and compartment syndrome after low-energy fracture of the distal radius: a case report. J Surg Orthop Adv. 2008;17(2):102–6.

Queipo-de-Llano Temboury A, Lara JM, Fernadez-de-Rota A, Queipo-de-Llano E. Anterior elbow dislocation with potential compartment syndrome: a case report. Tech Hand Up Extrem Surg. 2007;11(1):18–23.

Maru M, Varma S, Gill P. Acute compartment syndrome in the forearm following closed reduction and K-wiring of wrist fracture. Injury. 2005;36(10):1257–9.

Grottkau BE, Epps HR, Di Scala C. Compartment syndrome in children and adolescents. J Pediatr Surg. 2005;40(4):678–82.

Yuan PS, Pring ME, Gaynor TP, Mubarak SJ, Newton PO. Compartment syndrome following intramedullary fixation of pediatric forearm fractures. J Pediatr Orthop. 2004;24(4):370–5.

Kupersmith LM, Weinfeld SB. Acute volar and dorsal compartment syndrome after a distal radius fracture: a case report. J Orthop Trauma. 2003;17(5):382–6.

Mok DH, Charalambides C. Forearm compartment syndrome secondary to radial neck fracture in a child. A case report and review of the literature. Eur J Trauma. 2002;28(1):35–8.

Ring D, Waters PM, Hotchkiss RN, Kasser JR. Pediatric floating elbow. J Pediatr Orthop. 2001;21(4):456–9.

Blakemore LC, Cooperman DR, Thompson GH, Wathey C, Ballock RT. Compartment syndrome in ipsilateral humerus and forearm fractures in children. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 2000;376:32–8.

Summerfield SL, Folberg CR, Weiss AP. Compartment syndrome of the pronator quadratus: a case report. J Hand Surg Am. 1997;22(2):266–8.

Seiler JG 3rd, Valadie AL 3rd, Drvaric DM, Frederick RW, Whitesides TE Jr. Perioperative compartment syndrome. A report of four cases. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 1996; 78(4):600–2

Simpson NS, Jupiter JB. Delayed onset of forearm compartment syndrome: a complication of distal radius fracture in young adults. J Orthop Trauma. 1995;9(5):411–8.

Haasbeek JF, Cole WG. Open fractures of the arm in children. J Bone Joint Surg Br. 1995;77(4):576–81.

Brostrom LA, Stark A, Svartengren G. Acute compartment syndrome in forearm fractures. Acta Orthop Scand. 1990;61(1):50–3.

Royle SG. Compartment syndrome following forearm fracture in children. Injury. 1990;21(2):73–6.

Stockley I, Harvey IA, Getty CJ. Acute volar compartment syndrome of the forearm secondary to fractures of the distal radius. Injury. 1988;19(2):101–4.

Shall J, Cohn BT, Froimson AI. Acute compartment syndrome of the forearm in association with fracture of the distal end of the radius. Report of two cases. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 1986;68(9):1451–4.

Hernandez J Jr, Peterson HA. Fracture of the distal radial physis complicated by compartment syndrome and premature physeal closure. J Pediatr Orthop. 1986;6(5):627–30.

Matthews LS. Acute volar compartment syndrome secondary to distal radius fracture in an athlete: a case report. Am J of Sports Med. 1983;11(1):6–7. https://doi.org/10.1177/036354658301100103.

Cooney WP 3rd, Dobyns JH, Linscheid RL. Complications of colles’ fractures. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 1980;62(4):613–9.

Suzuki T, Suzuki K, Yamada H, Yamabe E, Iwamoto T, Sato K. Acute compartment syndrome of upper extremities with tendon ruptures. J Hand Surg Asian Pac. 2017;22(4):411–5.

Duckworth AD, Mitchell SE, Molyneux SG, White TO, Court-Brown CM, McQueen MM. Acute compartment syndrome of the forearm. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2012;94(10):e63.

Bae DS, Kadiyala RK, Waters PM. Acute compartment syndrome in children: contemporary diagnosis, treatment, and outcome. J Pediatr Orthop. 2001;21(5):680–8.

McQueen MM, Gaston P, Court-Brown CM. Acute compartment syndrome: who is at risk? J Bone Joint Surg Br. 2000;82(2):200–3.

Moed BR, Fakhouri AJ. Compartment syndrome after low-velocity gunshot wounds to the forearm. J Orthop Trauma. 1991;5(2):134–7.

Cohn BT, Shall J, Berkowitz M. Forearm fasciotomy for acute compartment syndrome: a new technique for delayed primary closure. Orthopedics. 1986;9(9):1243–6.

Matsen FA 3rd, Veith RG. Compartmental syndromes in children. J Pediatr Orthop. 1981;1(1):33–41.

Reigstad A, Hellum C. Volkmann’s ischaemic contracture of the forearm. Injury. 1980;12(2):148–50.

Mubarak SJ, Carroll NC. Volkmann’s contracture in children: aetiology and prevention. J Bone Joint Surg Br Vol. 1979;61-B(3):285–93. https://doi.org/10.1302/0301-620X.61B3.479251.

Morin RJ, Swan KG, Tan V. Acute forearm compartment syndrome secondary to local arterial injury after penetrating trauma. J Trauma. 2009;66(4):989–93.

Ghiorghiu Z, Tincu RC, Macovei RA, Tomescu D. The compartment syndrome associated with deep vein thrombosis due to rattlesnake bite: a case report. Balkan Med J. 2017;34(4):367–70.

Özkan A, Şentürk S, Tosun Z. Fasciotomy procedures on acute compartment syndromes of the upper extremity related to burns. Electron J Gen Med. 2015;12(4):326–33.

Suzuki T, Takeda K, Yoshida H, Iwamoto T, Sato K, Nakamura T. Acute compartment syndrome in the forearm with extensor and flexor tendon ruptures: a case report. JBJS Case Connector. 2014;4(4):e106.

Bucaretchi F, De Capitani EM, Hyslop S, Mello SM, Fernandes CB, Bergo F, et al. Compartment syndrome after South American rattlesnake (Crotalus durissus terrificus) envenomation. Clin Toxicol. 2014;52(6):639–41.

Hardwicke J, Srivastava S. Volkmann’s contracture of the forearm owing to an insect bite: a case report and review of the literature. Ann R Coll Surg Engl. 2013;95(2):e36–7.

Crawford B, Comstock S. Acute compartment syndrome of the dorsal forearm following noncontact injury. CJEM. 2010;12(5):453–6.

Soong M, DaSilva M. Acute forearm compartment syndrome secondary to digit avulsion injury: a case report. J Bone Joint Surg-Am Vol. 2009;91(2):435–7. https://doi.org/10.2106/JBJS.H.00737.

Choi G, Huang JL, Fowble V, Tucci J. Volar forearm compartment syndrome following flexor digitorum profundus muscle rupture in a 3-year-old girl. Am J Orthop (Belle Mead, NJ). 2008;37(6):E108–9.

Cohen J, Bush S. Case report: compartment syndrome after a suspected black widow spider bite. Ann Emerg Med. 2005;45(4):414–6.

Schumer ED. Isolated compartment syndrome of the pronator quadratus compartment: a case report. J Hand Surg Am. 2004;29(2):299–301.

Cosker T, Gupta S, Tayton K. Compartment syndrome caused by suction. Injury. 2004;35(11):1194–5.

Docker C, Titley OG. A case of forearm compartment syndrome following a ring avulsion injury. Injury. 2002;33(3):274–5.

Tachi M, Hirabayashi S, Kuroda E. Unusual development of acute compartment syndrome caused by a suction injury: a case report. Scand J Plast Reconstr Surg Hand Surg. 2001;35(3):329–30.

Sparkes JM, Kingston R, Keogh P, O’Flanagan SJ. Acute forearm compartment syndrome: report of three cases and a review of the literature. Ir J Med Sci. 2000;169(2):141–2.

Khan M, Hodkinson SL. Acute compartment syndrome–presenting as severe pain in an extremity out of proportion with the injury. J R Army Med Corps. 1997;143(3):165–6.

Jones DG, Theis JC. Acute compartment syndrome due to closed muscle rupture. Aust N Z J Surg. 1997;67(4):227–8.

Hussmann J, Kucan JO, Zamboni WA. Elevated compartmental pressures after closure of a forearm burn wound with a skin-stretching device. Burns. 1997;23(2):154–6.

Anderson WJ, Sterling DA. Posttraumatic compartment syndrome of the dorsal forearm: an unusual case. Orthopedics. 1997;20(3):265–6.

Shin LAY, Chambers H, Wilkins KE, Bucknell CA. Suction injuries in children leading to acute compartment syndrome of the interosseous muscle of the hand. J Hand Surg Am. 1996;21(4):675–8.

Kline SC, Moore JR. Neonatal compartment syndrome. J Hand Surg Am. 1992;17(2):256–9.

Aerts P, De Boeck HD, Casteleyn PP, Opdecam P. Deep volar compartment syndrome of the forearm following minor crush injury. J Pediatr Orthop. 1989;9(1):69–71.

Roberts RS, Csencsitz TA, Heard CW Jr. Upper extremity compartment syndromes following pit viper envenomation. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 1985;193:184–8.

Joseph FR, Posner MA, Terzakis JA. Compartment syndrome caused by a traumatized vascular hamartoma. J Hand Surg. 1984;9(6):904–7.

Gainor BJ. Closed avulsion of the flexor digitorum superficialis origin causing compartment syndrome. A case report. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 1984;66(3):467.

Tsur H, Yaffe B, Engel Y. Impending Volkmann’s contracture in a newborn. Ann Plast Surg. 1980;5(4):317–20.

Zhang D, Tarabochia M, Janssen SJ, Ring D, Chen N. Acute compartment syndrome in patients undergoing fasciotomy of the forearm and the leg. Int Orthop. 2019;43(6):1465–72.

Newmeyer WL, Kilgore ES Jr. Volkmann’s ischemic contracture due to soft tissue injury alone. J Hand Surg Am. 1976;1(3):221–7.

Komura S, Hirakawa A, Akiyama H, Matsushita Y, Masuda T, Nohara M. Forearm compartment syndrome concomitant with pseudoaneurysm of the anterior interosseous artery after minor penetrating injury. J Hand Surg Asian Pac. 2018;23(3):395–8.

Belyayev L, Rich NM, McKay P, Nesti L, Wind G. Traumatic ulnar artery pseudoaneurysm following a grenade blast: report of a case. Mil Med. 2015;180(6):e725–7.

Isik C, Demirhan A, Karabekmez FE, Tekelioglu UY, Altunhan H, Ozlu T. Forearm compartment syndrome owing to being stuck in the birth canal: a case report. J Pediatr Surg. 2012;47(11):e37–9.

Savage R. Compartment syndrome caused by false aneurysm. J Bone Joint Surg Br. 1990;72(5):923.

Lagerstrom CF, Reed RL 2nd, Rowlands BJ, Fischer RP. Early fasciotomy for acute clinically evident posttraumatic compartment syndrome. Am J Surg. 1989;158(1):36–9.

Oliver JD. Acute traumatic compartment syndrome of the forearm: Literature review and unfavorable outcomes risk analysis of fasciotomy treatment. Plast Surg Nurs. 2019;39(1):10–3.

Jimenez A, Marappa-Ganeshan R. Forearm compartment syndrome. Treasure Island (FL): StatPearls Publishing; 2021.

Funding

This research did not receive any specific grant from funding agencies in the public, commercial, or not-for-profit sectors.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

EA and KK conceived and designed the study and provided the research materials. EA, OA, AA, MA and AA collected and organized the data. EA, AA, MA and AA analyzed and interpreted the data. EA, KK, OA and AA wrote the initial and final drafts of the article. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Ethical approval and consent to participate

The authors confirm that this review had been prepared in accordance with COPE roles and regulations. Given the nature of the review, the IRB review was not required.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/. The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver (http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/) applies to the data made available in this article, unless otherwise stated in a credit line to the data.

About this article

Cite this article

Khoshhal, K.I., Alsaygh, E.F., Alsaedi, O.F. et al. Etiology of trauma-related acute compartment syndrome of the forearm: a systematic review. J Orthop Surg Res 17, 342 (2022). https://doi.org/10.1186/s13018-022-03234-x

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s13018-022-03234-x