Abstract

Objectives

It remains debatable if early mobilization (EM) yields a better clinical outcome than the late mobilization (LM) in adults with an acute and displaced distal radial fracture (DRF) of open reduction internal fixation (ORIF). Therefore, we aimed to perform a systematic review and meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials (RCTs), comparing clinical results with the safety of EM with LM following ORIF.

Methods

Databases such as Medline, Cochrane Central Register, and Embase were searched from Jan 1, 2000, to July 31, 2021, and RCTs comparing EM with LM for DRF with ORIF were included in the analysis. The primary outcome of study included disabilities of the Arm, Shoulder, and Hand (DASH) score at different follow-up times. Wherever the secondary outcomes included patient-rated wrist evaluation (PRWE), grip strength (GS), visual analog scale (VAS), wrist range of motion (WROM), and associated complications, the two independent reviewers did data extraction for the analysis. Effect sizes of outcome for each group were pooled using random-effects models; thereafter, the results were represented in the forest plots.

Results

Nine RCTs with 293 EM and 303 LM participants were identified and included in the study. Our analysis showed that the DASH score of the EM group was significantly better than LM group at the six weeks postoperatively (− 10.15; 95% CI − 15.74 to − 4.57, P < 0.01). Besides, the EM group also had better outcomes in PRWE, GS and WROM at 6 weeks. However, EM showed potential higher rate for implant loosening and/or fracture re-displacement complication (3.00; 95% CI 1.02–8.83, P = 0.05).

Conclusion

Functionally, at earlier stages, EM for patients with DRF of ORIF may have a beneficial effect than LM. The mean differences in the DASH score at 6 weeks surpassed the minimal clinically important difference; however, the potentially higher risk of implant loosening and/or fracture re-displacement cannot be ignored. Due to the lack of definitive evidence, multicenter and large sample RCTs are required for determining the optimal rehabilitation protocol for DRF with ORIF.

PROSPERO registration number: CRD42021240214 2021/2/28.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Distal radius fracture (DRF) is one of the most common fracture [1, 2]. Particularly in an aging society, the incidence of DRF will continue to grow [3, 4]. Despite the existing variations, in the view of significantly better results in the reduction and functional recovery of open reduction internal fixation (ORIF) [5], it has become the primary surgical technique for the treatment of such fractures [6, 7]. However, rehabilitation type and immobilization duration following the plate fixation of DRFs remain uncertain [8], whereas persistent plaster fixation has been repeatedly questioned as a conventional rehabilitation program [9]. For patients in the early mobilization (EM) group, the satisfaction level remains higher due to the self-opportunity of maintaining basic hygiene without any protective measures [10]. However, EM is controversial due to the local pain-associated complications, poor wound healing, implant loosening, loss of reduction, and internal fixation failure [11].

A randomized controlled study demonstrated that EM positively impacted the surgical treatment outcome and caused no additional complications compared to late immobilization (LM) [12]. Furthermore, a prospective study revealed that EM had better patient-reported outcomes and wrist range of motion (WROM). Meanwhile, it did not require multiple follow-ups and guidance from physiotherapists during rehabilitation [13]. Another study reported that the LM does not lead to decreased wrist motion compared to initial wrist motion [10, 14]. Furthermore, Andrade et al., have reported the comparative more use of opioids in the early active groups [15]. In the light of these results, after the surgery, the postoperative fixation time ranges from immediate mobilization to the 6 weeks of cast immobilization, based on the different practices of the surgeons [13, 16,17,18].

To the best of our knowledge, no evidence-based medical study compared the EM with the conventional LM after ORIF of DRF. Therefore, we performed systematic review and meta-analysis based on randomized controlled studies (RCTs) for exploring the advantage of EM protocol over LM protocol in respect to clinical outcomes and complications.

Materials and methods

Study method

Our systematic review with meta-analysis performed on the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA) guidelines (Additional file 1) [19]. Search strategy, trial selection, eligibility criteria, data collection, risk of bias assessment, and analysis process were duly conducted according to the predefined protocol (https://www.crd.york.ac.uk/PROSPERO/; PROSPERO: CRD42021240214).

Search strategy and trial selection

The databases such as Medline, Cochrane Central Register, and Embase were searched from Jan 1, 2000, to June 30, 2021. The keywords used to explore the potential published RCTs were as follows: “Early mobilization,” “Accelerated rehabilitation,” “Delayed motion,” “Distal radius fractures,” “Distal radius,” and “Randomized Controlled Trials.” After dataset de-duplication, all titles were further filtered, and only relevant abstracts were reviewed again. Finally, the full text of eligible trials was studied before making the final inclusion. Reference lists of identified studies were also cross-checked to prevent any overlooked relevant trials.

Inclusion criteria

Inclusion criteria were defined based on Population, Intervention, Comparison, and Outcome (PICO) method [20].

-

1.

Population: Adults ≥ 18 years with a diagnosed DRF from acute trauma and open reduction internal fixation treatment.

-

2.

Type of Intervention: Early mobilization group (immobilization period of ≤ 2 weeks); accelerated rehabilitation scheme (beginning of a passive and/or active wrist exercise program, immediately after internal fixation).

-

3.

Type of Comparison: Late mobilization group (more immobilization period > 2 weeks, and then start of exercise program); standard rehabilitation scheme (No movement of the wrist until the cast removal).

-

4.

Outcomes: At least one of the following results was required: Disabilities of the Arm, Shoulder, and Hand (DASH), Patient-Rated Wrist Evaluation (PRWE), grip strength (GS), visual analog scale (VAS), wrist range of motion (WROM) and associated complications.

-

5.

Type of Study Design: Prospective controlled clinical trials or Randomized Controlled Trials (RCTs) published in English.

Exclusion Criteria: (1) Studies on other limb fractures other than DRF and (2) studies reporting only the radiological result.

Data extraction

Two independent authors (KY T and HS) extracted raw data from the included studies using pre-designed data extraction tables. In the study, three or more arms were included. Then, the data were pooled from the treatment arms with the earliest motion group and the last motion group. In the studies not reporting numeric value, manual measurements of published charts were performed. Also, in the dataset, not written in standard form, the standard deviations were approximately as range/4 [21]. It is worth noting that the QuickDASH is a concept-retention version of DASH, which is similar to the complete DASH in terms of properties and scores [22]. We contacted the corresponding author to obtain the dataset, for studies containing the result of interest but with original data non-availability. Besides, any disagreements in the process were also resolved by the general consensus.

Risk of bias assessment

The risk of bias assessment was conducted based on the Cochrane Risk of Bias Tool [23]. In addition, the quality of included RCTs was also evaluated from the following criteria: random sequence generation, allocation concealment, blinding of participants and personnel, blind outcome assessment, incomplete outcome data, selective reporting, and other sources of biases in the study. As a result, the overall quality of each study was classified as unclear, low, or high risk of bias. Meanwhile, articles with low risk of bias were also defined as four or more meeting criteria.

Evidence assessment with the GRADE approach

The evidence assessment was performed using the guidelines of the Grading of Recommendations, Assessment, Development, and Evaluation (GRADE). The outcomes were assessed for the following elements: risk of bias, inconsistency, indirectness, imprecision, and publication bias.

Statistical analysis

Review Manager Software (Revman 5.3.3, Cochrane Collaboration, Oxford, United Kingdom) was used for the pooled data statistical analyses. The continuous variable outcomes (DASH, PRWE, VAS, GS, WROM) were represented as mean difference (MD) with a 95% confidence interval (95% CI). Similarly, dichotomous outcomes (complications) were represented as risk ratio (RR) with 95% CI. Heterogeneity among the studies was also assessed using the I2 test [24], where I2 > 50% indicates significant heterogeneity and I2 < 50% was considered to have low heterogeneity; thus for the analysis, the random-effect model and fixed-effect model were used, respectively. Additionally, a P value of < 0.05 was considered statistically significant. Meanwhile, the MD of DASH was compared with the minimal clinically important difference (MCID), estimated at 10 in DRF to evaluate its clinical relevance [25]. The sensitivity analysis was performed to explore the reliability of the outcomes. Furthermore, publication bias was examined by Begg’s rank correlation and Egger’s weighted regression method.

Results

Search outcomes and trial characteristics

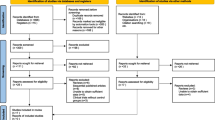

As shown in Fig. 1, a total of 981 potentially relevant articles were retrieved from all the databases, but only 243 of them were retained for study, after the removal of the duplicates. Following the screening of the titles and abstracts, 221 articles were further excluded. The remaining 22 full-text articles were carefully evaluated, and 13 were excluded after the final screening due to variable reasons. Finally, 9 RCTs meeting the inclusion criteria were taken for comprehensive evaluation of this meta-analysis [10, 12,13,14,15, 17, 18, 26, 27]. Quality assessment of the included studies is shown in Fig. 2, and no investigation was excluded on bias concern. The essential characteristics of the included studies are also tabulated in Table 1. The sample sizes of the 9 studies ranged between 30 and 119. Whereas between the 293 EM and 303 LM cases, no significant differences were observed in participants demographics or fracture type.

Primary outcome

DASH scores

As shown in Fig. 3, DASH scores were available in 8 studies [10, 12,13,14,15, 17, 18, 26] for total of 546 patients. The DASH scores in EM were significantly better when compared with LM at 6 and 24 weeks postoperatively, with mean differences (MDs) of − 10.15 (95% CI − 15.74 to − 4.57, P < 0.01) and − 1.77 (95% CI − 3.09 to − 0.45, P < 0.01), respectively. Interestingly, MD at the 6th week reached the MCID value of 10. However, EM had a similar outcome to LM at the 12th and 48th week postoperatively, with MDs of − 1.61 (95% CI − 4.37–1.14, P = 0.25) and 0.37 (95% CI − 1.05–1.79, P = 0.61), respectively. The summarized outcomes were also evaluated as a moderate or lower heterogeneity, with I2 = 77%, 53%, 0%, and 0% for the 6th, 12th, 24th, and 48th week postoperatively, respectively.

Secondary outcomes

PRWE scores

As shown in Fig. 4, four studies [12, 13, 17, 18] with 274 patients reported data on PRWE and lower heterogeneity (I2 = 31%, I2 = 12%, I2 = 0%) for PRWE scores at 6th, 12th, and 48th week postoperatively. The outcome showed that the EM group had improved PRWE scores than the LM group, with MD of − 12.47 (95% CI − 18.10 to − 6.84, P < 0.01) at 6 weeks postoperatively.

VAS scores

As shown in Fig. 5, five studies [12,13,14,15, 18] with 281 patients had data on VAS scores. Lower heterogeneity was found for the VAS scores (I2 = 0%, I2 = 12%, I2 = 0%) at 6th, 12th, and 48th week postoperatively, although no significant differences were observed between EM and LM group (P > 0.05).

GS

As shown in Fig. 6, seven studies [10, 12,13,14, 17, 26, 27] with 518 patients described data on the grip strength (Kg). The summarized outcomes were evaluated as a slightly moderate or lower heterogeneity, with I2 = 0%, 55%, 10%, 75%, and 0% at the 2nd, 6th, 12th, 24th, and 48th week postoperatively. Meta-analysis showed that the EM group had a statistically better grip strength than the LM group at 2nd and 6th week postoperatively, with MD of 2.30 (95% CI 1.10–3.51, P < 0.01) and 3.11 (95% CI 1.27–4.95, P < 0.01), respectively.

WROM

As shown in Figs. 7, 8, 9, 10, 11 and 12, the WROM was reported in six directions in the pooled flexion, extension, supination, pronation, radial deviation, and ulnar deviation. At the 6th week, flexion (MD = 10.87, 95% CI 2.30–19.45, P = 0.01), extension (MD = 9.06, 95% CI 3.24–14.88, P < 0.01), pronation (MD = 3.93, 95% CI 1.37–6.50, P < 0.01), supination (MD = 5.63, 95% CI 2.10–9.16, P < 0.01) and radial deviation (MD = 1.99, 95% CI 0.46–3.51, P = 0.01) had better performance in the EM group in comparison with the LM group.

Complications

As shown in Fig. 13, nine RCTs [10, 12,13,14,15, 17, 18, 26, 27] with 596 patients recorded related complication rates. However, no heterogeneity (I2 = 0%, I2 = 0%) from the implant loosening and/or fracture re-displacement complication and overall complications was detected. Interestingly, the pooled result on the rate of implant loosening and/or fracture re-displacement complications showed that the EM led to a potentially higher proportion than LM, with RR of 3.00 (95% CI 1.02–8.83, P = 0.05). The overall complications rate outcome had no statistical difference between the two groups (RR = 1.16, 95% CI 0.72–1.87, P = 0.54). The detailed occurrence of complications is listed in Table 2.

Heterogeneity analyses

Heterogeneity in data was resulted due to the inconsistencies found in the intervention protocol between the included RCTs. The sensitivity analysis was conducted to explore the impact of individual studies by excluding one study at each time. In the DASH, GS, flexion, extension, pronation, and ulnar deviation pooled analysis, heterogeneity showed a significant reduction when excluding one or two studies. Still, no significant difference was observed in comparison with previous results. The detailed outcomes are shown in Additional file 2.

Publication bias

Begg's rank correlation and Egger's weighted regression analysis were performed separately to investigate the publication bias. A P value of < 0.05 was considered publication bias. The P values for all pooled analyses are presented in Additional file 3(all P > 0.05). No obvious publication bias was found in all the studied outcomes.

Quality of the evidence in the GRADE system

As shown in Additional file 4, a total of 43 outcomes, including subgroup analysis of this meta-analysis, were evaluated by the GRADE system. The evidence quality for all outcomes was either moderate or low, suggesting our meta-analysis had overall moderate evidence quality.

Discussion

The primary finding of this study revealed that EM yielded a significantly better DASH score than LM at 6 weeks (MD of − 10.15 points) postoperatively, in patients with acute displaced DRFs followed by ORIF. Moreover, this difference reached the MCID defined as 10 points in DASH [28]. Although the mean difference at 24-week DASH between EM and LM was statistically different (MD = −1.77 points, P < 0.05), which did not reach MCID (10 points). EM group also outperformed the LM group in PRWE at 6 weeks. However, the EM group had a similar clinical outcome score at 12 weeks to final follow-up (≥ 1 year) compared to the LM. The primary finding revealed that at the earlier stages, the function of injured limbs recovers more quickly in EM cohorts with DRF of ORIF.

Secondary findings at postoperative 2nd and 6th week showed a significantly better GS for EM compared to the LM. Nonetheless, comparing with LM, EM might be involved in a similar VAS score at 1-year follow-up. Regarding WROM, in postoperative 6th week, EM showed significant improvement in terms of flexion, extension, pronation, supination, and radial deviation than LM. However, EM showed a potentially higher proportion of implant loosening and/or fracture re-displacement complications than LM (P = 0.05).

Postoperative EM improved the patient's quality of life and physical comfort [10, 29], and therefore assures the individuals early return to activities of daily living and work. Despite the lack of supporting studies demonstrating its effectiveness, immobilization has been empirically used to provide analgesia after surgery [30, 31]. The latest Cochrane Database Review published in 2015 by Handoll et al. [8] on rehabilitation for DRFs pointed out that as in 2006 [32], there is a lack of sufficient evidence about the effectiveness of the various rehabilitation programs after ORIF for DRF. Considering the biomechanical studies, the fixation of DRFs with a locking plate provides a five times higher stability than the forces caused by the active finger movement [33], suggesting the internal fixation treatment offers a strong fixation that meets the need for the early mobilization of these patients. However, the included studies had slight variable definitions of early mobilization. For example, Sørensen et al. [10] instructed the EM group to start nonweight-bearing exercises of the wrist and fingers from the postoperative first day, whereas Dennison et al. [18] required EM patients to gradually start active and passive wrist exercises on the 14th day after surgery. However, most of the studies included gradual movement of the wrist joints without a rigid fixation within 2 weeks or immediately after the operation.

To obtain a comparable and conclusive outcome, researches on EM versus LM after ORIF for DRFs with more high-quality large RCTs were included. The results suggested that patients treated with EM may get better clinical outcomes at an early stages which was in-concurrence with the previous studies [13, 17, 18, 26, 27]. As there was no statistical difference observed for the long term between the two groups, the difference in the functional results during the early stages between the two groups might have caused by the residual rigidity of the cast in the LM group [17]. However, at the 6th week, the pain scores of the two groups were similar, which was consistent with the study of Dennison et al. [17]. Furthermore, these results were possibly influenced by the imbalance in opioid use between the two groups. Andrade et al. [15] have shown that patients with EM tend to use more tramadol; therefore, we could not make a clear conclusion on the pain score. However, the pooled analysis showed that the EM group had a potentially higher risk of implant loosening and/or fracture re-displacement complication (P = 0.05), which occurred 5.5 times more (11:2) in EM than the LM group. Although the slight difference in implant loosening could be a complication resulting from immature surgical technology [10], which is still a new discovery compared to the previous literatures that compared EM with LM [13, 17, 27]. EM for patients with DRF after ORIF fracture positively affects functional recovery, but the risk of failure for fracture healing must also be considered [17], as it increases the risk of secondary surgery for these patients. The complications do have negative impact on healthcare budget as well as on the patient’s total well-being. Consequently, EM is not completely safe and flawless, so we recommend in exercise caution for extrapolating our outcomes, especially for the health care policymakers and patients.

The current study had some limitations. Firstly, our study was limited by the number of matches and available RCTs in the database; therefore, we could not perform the subgroup analysis and the pooled analysis for radiographic outcomes. Secondly, the included patients in each of the 9 RCTs were slightly different for the age bracket and mechanism of injury, as DRF in the elderly is often caused by low energy injury, while in young people, it is often associated with high energy injury and accompanied by polytrauma. Therefore, our results may vary due to variable age range. Thirdly, variation in internal fixed implants of included studies may also affect the outcomes. Fourthly, our research does not have a cost–benefit analysis as we could not remark on the potential cost differences of EM from the perspective of patients or society. Consequently, we could not remark on whether EM has the theoretical advantage of returning to work faster than LM. Lastly, each study had a different detailed rehabilitation program for the EM, which had an inherent impact on the functional scores.

Conclusion

We showed that although EM had significantly better DASH, PRWE, GM, and WROM at earlier stages, EM and LM had similar clinical outcomes during the long-term follow-up period. Moreover, studied cases had a higher potential for implant loosening and/or fracture re-displacement complication rate when subjected to EM. Therefore, in the future, the optimal rehabilitation protocol for DRF of ORIF should be individualized, depending on the fracture types and degree of osteoporosis.

Availability of data and materials

The data sets supporting the results of this article are included within the article.

Abbreviations

- DRF:

-

Distal radius fracture

- ORIF:

-

Open reduction internal fixation

- EM:

-

Early mobilization

- LM:

-

Late mobilization

- DASH:

-

Disabilities of the Arm, Shoulder, and Hand

- PRWE:

-

Patient-Rated Wrist Evaluation

- VAS:

-

Visual analog scale

- GS:

-

Grip strength

- WROM:

-

Wrist range of motion

- MCID:

-

Minimal clinically important difference

References

Singer BR, McLauchlan GJ, Robinson CM, Christie J. Epidemiology of fractures in 15,000 adults: the influence of age and gender. J Bone Joint Surg Br. 1998;80(2):243–8.

Smeraglia F, Del Buono A, Maffulli N. Wrist arthroscopy in the management of articular distal radius fractures. Br Med Bull. 2016;119(1):157–65.

Diaz-Garcia RJ, Oda T, Shauver MJ, Chung KC. A systematic review of outcomes and complications of treating unstable distal radius fractures in the elderly. J Hand Surg Am. 2011;36(5):824-835.e822.

Figl M, Weninger P, Jurkowitsch J, Hofbauer M, Schauer J, Leixnering M. Unstable distal radius fractures in the elderly patient–volar fixed-angle plate osteosynthesis prevents secondary loss of reduction. J Trauma. 2010;68(4):992–8.

Franceschi F, Franceschetti E, Paciotti M, Cancilleri F, Maffulli N, Denaro V. Volar locking plates versus K-wire/pin fixation for the treatment of distal radial fractures: a systematic review and quantitative synthesis. Br Med Bull. 2015;115(1):91–110.

Rozental T, Blazar P, Franko O, Chacko A, Earp B, Day C. Functional outcomes for unstable distal radial fractures treated with open reduction and internal fixation or closed reduction and percutaneous fixation. A prospective randomized trial. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2009;91(8):1837–46.

Grewal R, MacDermid J, King G, Faber K. Open reduction internal fixation versus percutaneous pinning with external fixation of distal radius fractures: a prospective, randomized clinical trial. J Hand Surg. 2011;36(12):1899–906.

Handoll HH, Elliott J. Rehabilitation for distal radial fractures in adults. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2015;9:Cd000324.

Valdes K. A retrospective pilot study comparing the number of therapy visits required to regain functional wrist and forearm range of motion following volar plating of a distal radius fracture. J Hand Ther. 2009;22(4):312–8 (quiz 319).

Sørensen TJ, Ohrt-Nissen S, Ardensø KV, Laier GH, Mallet SK. Early mobilization after volar locking plate osteosynthesis of distal radial fractures in older patients—a randomized controlled trial. J Hand Surg Am. 2020;45(11):1047-1054.e1041.

Ikpeze TC, Smith HC, Lee DJ, Elfar JC. Distal radius fracture outcomes and rehabilitation. Geriatr Orthop Surg Rehabil. 2016;7(4):202–5.

Quadlbauer S, Pezzei C, Jurkowitsch J, Kolmayr B, Keuchel T, Simon D, Hausner T, Leixnering M. Early rehabilitation of distal radius fractures stabilized by volar locking plate: a prospective randomized pilot study. J Wrist Surg. 2017;6(2):102–12.

Clementsen S, Hammer O, Šaltytė Benth J, Jakobsen R, Randsborg P. Early mobilization and physiotherapy vs. late mobilization and home exercises after ORIF of distal radial fractures: a randomized controlled trial. JB JS Open Access. 2019;4(3):66.

Lozano-Calderón S, Souer S, Mudgal C, Jupiter J, Ring D. Wrist mobilization following volar plate fixation of fractures of the distal part of the radius. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2008;90(6):1297–304.

Andrade-Silva FB, Rocha JP, Carvalho A, Kojima KE, Silva JS. Influence of postoperative immobilization on pain control of patients with distal radius fracture treated with volar locked plating: a prospective, randomized clinical trial. Injury. 2019;50(2):386–91.

Bruder AM, Shields N, Dodd KJ, Hau R, Taylor NF. A progressive exercise and structured advice program does not improve activity more than structured advice alone following a distal radial fracture: a multi-centre, randomized trial. J Physiother. 2016;62(3):145–52.

Watson N, Haines T, Tran P, Keating J. A comparison of the effect of one, three, or six weeks of immobilization on function and pain after open reduction and internal fixation of distal radial fractures in adults: a randomized controlled trial. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2018;100(13):1118–25.

Dennison DG, Blanchard CL, Elhassan B, Moran SL, Shin AY. Early versus late motion following volar plating of distal radius fractures. Hand (N Y). 2020;15(1):125–30.

Preferred reporting items for systematic review and meta-analysis protocols (PRISMA-P) 2015: elaboration and explanation. BMJ.2016;354:i4086.

Schardt C, Adams MB, Owens T, Keitz S, Fontelo P. Utilization of the PICO framework to improve searching PubMed for clinical questions. BMC Med Inform Decis Mak. 2007;7:16.

Wan X, Wang W, Liu J, Tong T. Estimating the sample mean and standard deviation from the sample size, median, range and/or interquartile range. BMC Med Res Methodol. 2014;14:135.

Beaton DE, Wright JG, Katz JN. Development of the QuickDASH: comparison of three item-reduction approaches. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2005;87(5):1038–46.

Whiting P, Savović J, Higgins JPT, Caldwell DM, Reeves BC, Shea B, Davies P, Kleijnen J, Churchill R. ROBIS: a new tool to assess risk of bias in systematic reviews was developed. Recent Prog Med. 2018;109(9):421–31.

Higgins JP, Thompson SG. Quantifying heterogeneity in a meta-analysis. Stat Med. 2002;21(11):1539–58.

Jaeschke R, Singer J, Guyatt GH. Measurement of health status. Ascertaining the minimal clinically important difference. Control Clin Trials. 1989;10(4):407–15.

Brehmer JL, Husband JB. Accelerated rehabilitation compared with a standard protocol after distal radial fractures treated with volar open reduction and internal fixation: a prospective, randomized, controlled study. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2014;96(19):1621–30.

Zeckey C, Späth A, Kieslich S, Kammerlander C, Böcker W, Weigert M, Neuerburg C. Early mobilization versus splinting after surgical management of distal radius fractures. Dtsch Arztebl Int. 2020;117(26):445–51.

Franchignoni F, Vercelli S, Giordano A, Sartorio F, Bravini E, Ferriero G. Minimal clinically important difference of the disabilities of the arm, shoulder and hand outcome measure (DASH) and its shortened version (QuickDASH). J Orthop Sports Phys Ther. 2014;44(1):30–9.

Saving J, Enocson A, Ponzer S, Mellstrand Navarro C. External fixation versus volar locking plate for unstable dorsally displaced distal radius fractures-a 3-year follow-up of a randomized controlled study. J Hand Surg. 2019;44(1):18–26.

Hill JR, Navo PD, Bouz G, Azad A, Pannell W, Alluri RK, Ghiassi A. immobilization following distal radius fractures: a randomized clinical trial. J Wrist Surg. 2018;7(5):409–14.

Salibian AA, Bruckman KC, Bekisz JM, Mirrer J, Thanik VD, Hacquebord JH. Management of unstable distal radius fractures: a survey of hand surgeons. J Wrist Surg. 2019;8(4):335–43.

Handoll HH, Madhok R, Howe TE. Rehabilitation for distal radial fractures in adults. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2006;3:CD003324.

Osada D, Fujita S, Tamai K, Iwamoto A, Tomizawa K, Saotome K. Biomechanics in uniaxial compression of three distal radius volar plates. J Hand Surg Am. 2004;29(3):446–51.

Acknowledgements

Mao Nie was supported by the Kuanren Talents Program of the second affiliated hospital of Chongqing Medical University.

Funding

Not applicable.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

All named authors have substantially contributed to conducting the underlying research and drafting this manuscript. ZB D and JP W designed the experiments. KY T and HS searched articles, extracted data. TW made the analysis. ZB D and JP W wrote this manuscript. FB L and MN examined the original study data, reviewed the analysis of data, and approved the final manuscript. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

Not applicable.

Consent to participate

Not applicable.

Consent to publish

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare that no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary Information

Additional file 1.

PRISMA checklist.

Additional file 2.

Heterogeneity analyses.

Additional file 3.

Publication bias of all summarized outcomes.

Additional file 4.

Quality of evidence according to the GRADE criteria.

Rights and permissions

This article is published under an open access license. Please check the 'Copyright Information' section either on this page or in the PDF for details of this license and what re-use is permitted. If your intended use exceeds what is permitted by the license or if you are unable to locate the licence and re-use information, please contact the Rights and Permissions team.

About this article

Cite this article

Deng, Z., Wu, J., Tang, K. et al. In adults, early mobilization may be beneficial for distal radius fractures treated with open reduction and internal fixation: a systematic review and meta-analysis. J Orthop Surg Res 16, 691 (2021). https://doi.org/10.1186/s13018-021-02837-0

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s13018-021-02837-0