Abstract

Background

Juvenile hip osteoarthritis is often the end result of congenital conditions or acquired hip ailments occurred during the paediatric age. This study evaluated the middle term results of total hip arthroplasty for end-stage juvenile hip osteoarthritis.

Materials and methods

This is a retrospective analysis of prospectively collected data on a cohort of 10 consecutive patients (12 hips), aged between 14 and 20 at operation, who underwent cementless total hip arthroplasty for end-stage juvenile secondary hip osteoarthritis in two orthopaedic tertiary referral centres between 2009 and 2018.

Results

Juvenile hip osteoarthritis occurred as a consequence of developmental dysplasia of the hip, Legg-Calvé-Perthes disease, femoral head necrosis or slipped capital femoral epiphysis. All patients showed a significant improvement in Harris Hip Score (p < 0.01) at 3.3 years average follow-up (range 0.7–10.1 years).

Conclusion

The management of juvenile hip osteoarthritis following developmental dysplasia of the hip, Legg-Calvé-Perthes disease, femoral head necrosis or slipped capital femoral epiphysis is still challenging. Careful preoperative planning is essential to achieve good outcomes and improve the Harris Hip Score in these young patients. Total hip arthroplasty is a suitable option for end-stage secondary juvenile hip osteoarthritis, when proximal femoral osteotomies and conservative treatments fail to improve patients’ symptoms and quality of life.

Level of evidence

IV

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Osteoarthritis of the hip may be the end result of congenital or acquired hip conditions occurred during the juvenile age [1]. Developmental dysplasia of the hip (DDH), Legg-Calvé-Perthes disease (LCPD), slipped capital femoral epiphysis (SCFE) and hip joint infections are the most common cause of juvenile hip osteoarthritis (JHOA) [2]. The complex management and the catastrophic consequences of these conditions justify the active research interest in this field [3,4,5,6]. DDH ranges from mild dysplasia of the acetabulum to frank dislocation of the hip [7] and is one of the most common congenital deformities of the lower limb [8]. Up to 35% of DDH patients develop idiopathic avascular necrosis (AVN) 5 years after conservative treatment and up to 32.9% develop AVN 10 years after surgical treatment [9].

LCPD, with an incidence between 4 and 32 per 100,000 population per year, can be complicated by AVN [10]. The prognosis of LCPD is more favourable in patients with early onset regardless of treatment, but exceptions remain common [11]. Predicting which child will need a salvage procedure remains a major challenge, but approximately 5% of the affected children will require a total hip arthroplasty (THA) [12].

There seems to be an increased risk of hip osteonecrosis after systemic glucocorticoid administration in young patients [13]. Glucocorticoids negatively influence skeletal remodelling in children [14]. A strong association of AVN with high-dose glucocorticoid therapy has been reported in systemic diseases [15,16,17].

The complication rate after SCFE treatment is difficult to assess [18], given the lack of standardized clinical data reporting and multicentre studies. A recent study reported an overall 29.4% AVN rate in a cohort of patients with stable SCFE treated with modified Dunn procedure [2], compared to a cohort of patients with unstable slips, who experienced a 6% AVN rate [19]. A 4% incidence of anterolateral hip instability was also found after modified Dunn procedure [20].

Septic hip arthritis is managed by surgical drainage in patients younger than 10, open arthrotomy and lavage in older children [21] or hip arthroscopy [22]. The presentation of paediatric septic arthritis of the hip may be dramatic and sometimes needs a major surgery [23].

In most cases, the sequelae of paediatric hip abnormalities require THA in adulthood [24]. Nevertheless, when disability from end-stage JHOA compromise the daily living of these young patients, THA could be required in the paediatric age range [3, 25]. These patients and their parents do not usually accept a function-limiting option such as hip resection or arthrodesis [26, 27]. Furthermore, the adequate timing of this kind of surgery is controversial. The management of these paediatric conditions is particularly challenging because of the profound alterations in hip anatomy, sequelae of the previous surgery and limb length discrepancy [28].

Surface arthroplasty allows to preserve bone stock and could be easily converted to THA in case of implant failure [29]. Nevertheless, the difficult learning curve and the higher revision rate of surface arthroplasty make THA the treatment of choice in young patients [30,31,32]. The clinical outcome of THA in children, adolescents and young adults is largely unknown and difficult to evaluate [6].

This study evaluated the reliability of THA in the management of end-stage JHOA.

Materials and methods

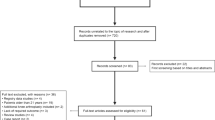

With appropriate Institutional Review Board approval, we retrospectively reviewed all patients affected by end-stage secondary JHOA who had undergone cementless THA between 2009 and 2018 at two major orthopaedic hospitals (Table 1). All patients were operated by two surgeons (C.M.S. and A.D.G.). For all patients, clinical features, hip pathologies leading to JHOA, prior surgeries, surgical approach for THA, implant type, surgical time, length of stay, and complications were recorded (Table 2). We also recorded the surgical approach used (Table 3).

Clinical outcomes were assessed comparing the Harris Hip Score (HHS) administered before THA and at the last follow-up (Table 1). Serial anteroposterior and axial radiographs of the operated joints were reviewed to assess the position of the implant and possible signs of loosening and wear.

Statistical analysis was performed using GraphPad Prism 6.0 software (GraphPad Software Inc., La Jolla, CA, USA). Student’s t test was applied to assess any statistical difference between pre- and postoperative clinical findings, with a p < 0.05 considered statistically significant).

Results

Ten consecutive patients (12 hips) affected by JHOA, aged between 14 and 20 years old, were reviewed. Among the conditions causing JHOA, SCFE affected five patients, LCPD two, and DDH two (both hips in a single patient) (Table 1). Patient no. 2 developed bilateral osteonecrosis of femoral head after being treated for acute lymphoblastic leukaemia with chemotherapy and glucocorticoids for 2 years.

Most patients had undergone other forms of hip surgery prior to THA: 3 Dunn procedures, 2 screw fixation, one Chiari’s pelvic osteotomy and one arthrodiatasis (Table 1, Figs. 1 and 2). All the operated patients underwent hardware removal before THA surgery. The average age at the time of THA was 17.0 years (range 14–20 years).

The THA procedure was performed through a direct lateral approach in 4 patients, tissue-sparing direct anterior approach in 3 patients and a posterolateral approach in 5 patients. Overall, the average surgical time was 126 min (range 85–230 min) and was longer for the direct anterior approach, even though statistical significance was not reached. The average length of stay in the orthopaedic unit was 8.1 days (range 5–15 days). All patients were then transferred to the rehabilitation unit (mean length of stay 15.9 days, range 12–22 days). The average duration of follow-up was 3.3 years (range 0.7–10.1 years).

Comparing the preoperative and postoperative HHS, the score improved significantly in all patients (mean preoperative HHS 36.1 versus mean postoperative HHS 94.0, p < 0.01). There were no complications except for one transient femoral nerve palsy (patient no. 1), resolved without any further treatment in 2 months and two hip dislocations in the posterolateral approach group. Patient no.7 dislocated in the first postoperative day and underwent closed reduction under sedation on the same day. Patient no. 9 underwent right hip dislocation in the second postoperative day and the following day underwent open reduction and substitution of the acetabular insert with a hooded anti-dislocation polyethylene insert.

Discussion

Total hip arthroplasty has become a safe routine procedure in middle-aged and elderly population with predictably good outcomes [33, 34]. The treatment of paediatric hip disorders secondary to SCFE, LCPD, femoral head necrosis, and DDH still presents a challenge. Data on the long-term follow-up in adolescents and high-demand young adults is limited. Compared to the adult population, such patients experience more complications and earlier revision from aseptic loosening of either the acetabular, more common or the femoral component [35, 36]. For these reasons, we reserve THA to those patients who have very serious limitations in everyday life from hip pain and loss of function and after conservative treatments failure [6]. THA in severe hip diseases in young individuals is technically difficult, as the proximal femoral geometry and acetabular orientation may be aberrant [28]. A careful preoperative planning in paediatric hip disease is crucial to obtaining good outcomes; the choice of the most suitable implant must be suited to the anatomy of each individual patient. In this respect, modular implants may help surgeons to restore femoral version and offset [37].

The medical literature reports increased operative time and complication rates when the removal of previously implanted hardware is performed at the same time of THA [38]. This supports routine implant removal in children with a high likelihood of future THA [39]. In most of these patients, the choice of the appropriate surgical approach requires an understanding of the local anatomy to optimize joint visualization [28]. A longer surgical time seems to be related (although in the present series, statistical significance was not reached) to the use of the anterior approach for THA.

The anterior and lateral approach may have a lower rate of dislocations in the immediate postoperative period compared to the posterolateral approach. In our patients, it is difficult to understand whether this different dislocation rate resulted purely from the different surgical approach or the greater average age of the posterolateral approach cohort (Table 2). In fact, the older the patient, the worse the hip deformity from the original condition [40] (Table 3). On the other hand, preservation of the posterior soft tissues may also explain the lower dislocation rate observed with the lateral and anterior approaches compared to the posterior one. A meta-analysis reported an 8 times greater dislocation rate when soft tissue repair was not performed in adults operated using the posterior approach [41]. Adjusting femoral anteversion while respecting acetabular anteversion in THA in paediatric hip disorders could effectively prevent dislocation, enhance the reliability of cup-bone osteointegration and reduce the risk of hip iliopsoas pain after THA. In our opinion, minimal technical modifications on these patients allow to obtain better results. In paediatric hip diseases, careful reconstruction of the posterior capsule and external rotators may be fundamental to decrease the risk of postoperative dislocation when using the posterior approach [41]. Furthermore, the only patient (patient 9) who underwent a THA revision with insert substitution after dislocation had been operated on for DDH. Attention should be paid during surgical planning especially for this subgroup of patients. In fact, instability is the fourth cause of THA failure in young patients, but the second cause of failure in THA performed for DDH, comparable in frequency for revision for acetabular loosening and wear [36].

In any case, THA clearly improves the HHS also in these young patients, and our results are in line with the most recent literature [42]. Nevertheless, the correct timing of this surgery remains unknown. We do not know whether it is better for a patient to undergo THA when serious functional limitations start or whether it is better to wait for symptoms to become severely disabling, forcing these patients to a lower quality of life for months or years before proposing THA. The patients reported in this case series had not undergone regenerative medicine attempts before THA. This reflects the severe osteoarthritic changes that all patients showed at presentation. Also, 4 patients had already undergone osteotomies. Osteotomies are still a good solution to gain time before THA. Nevertheless, as for regenerative medicine, they are contraindicated when severe osteoarthritic changes involve both the femoral head and the acetabulum, as was the case for the patients reported in the present investigation [43].

For less severe osteoarthritis, we consider two additional factors in the surgical decision-making process. The first are patients’ symptoms. Severe functional impairment during adolescence could impact negatively on the emotional sphere, and THA allows a more rapid and long-term recovery than osteotomies. The second factor is the severity of osteoarthritis. An osteotomy performed on an already osteoarthritic bone would at best result in only a short-term improvement of symptoms and could represent a complicating factor for the future THA surgery [39]. Furthermore, regardless of whether the osteotomy fixation hardware is removed at another surgery, or during the index THA, thus prolonging the surgical times, the risk of subsequent periprosthetic joint infection is theoretically increased [44]. In general, we prefer to remove the metalwork, if previous surgery has been undertaken, well before the arthroplasty is performed [39]. Further studies are necessary to answer these legitimate questions and assess the safest surgical approach for these young patients.

We acknowledge that this study has several limitations. The main limitation is the limited sample size and the different follow-up times; given the early diagnosis and the successful treatment of the less severe presentations of the hip developmental diseases, JHOA has currently become relatively rare [6]. We suspect that multicentre studies will be necessary to collect enough data on these challenging patients and randomized controlled trials will be difficult to perform.

Conclusions

Hip replacement in carefully selected young patients is safe and reliable and should be considered after conservative management has failed to restore hip function. In our cohort, THA demonstrated maintenance of improved clinical outcomes at 3.3 years from the index procedure. The right timing for THA remains unknown, although strongly conditioned by the quality of life of these patients.

Careful preoperative planning is crucial, as technical modifications are sometimes mandatory to adapt the THA procedure to the abnormal anatomy of each patient.

Availability of data and materials

All data generated or analysed during this study are included in this published article.

Abbreviations

- DDH:

-

Developmental dysplasia of the hip

- SCFE:

-

Slipped capital femoral epiphysis

- JHOA:

-

Juvenile hip osteoarthritis

- AVN:

-

avascular necrosis

- THA:

-

Total hip arthroplasty

- HHS:

-

Harris Hip Score

References

Kraus C, Ayyala RS, Kazam JK, Wong TT. Imaging of juvenile hip conditions predisposing to premature osteoarthritis—erratum. RadioGraphics. 2018;38:662.

Schmitz MR, Blumberg TJ, Nelson SE, Sees JP, Sankar WN. What’s new in pediatric hip? J. Pediatr. Orthop. 2018. p. e300–4.

Restrepo C, Lettich T, Roberts N, Parvizi J, Hozack WJ. Uncemented total hip arthroplasty in patients less than twenty-years. Acta Orthop Belg. 2008;74:615–22.

Callaghan JJ. Results of primary total hip arthroplasty in young patients. J. Bone Jt. Surg. - Ser. A. 1993. p. 1728–34.

Clohisy JC, Oryhon JM, Seyler TM, Wells CW, Liu SS, Callaghan JJ, et al. Function and fixation of total hip arthroplasty in patients 25 years of age or younger. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 2010. p. 3207–13.

Shrader MW. Total hip arthroplasty and hip resurfacing arthroplasty in the very young patient. Orthop. Clin. North Am. 2012. p. 359–67.

Aronsson DD, Goldberg MJ, Kling TF Jr., Roy DR. Developmental dysplasia of the hip.[Erratum appears in Pediatrics 1994 Oct;94(4 Pt 1):470]. Pediatrics. 1994;94:201–8.

Bialik V, Bialik GM, Blazer S, Sujov P, Wiener F, Berant M. Developmental dysplasia of the hip: a new approach to incidence. Pediatrics. 1999;103:93–9.

Gardner ROE, Bradley CS, Sharma OP, Feng L, Shin MEJ, Kelley SP, et al. Long-term outcome following medial open reduction in developmental dysplasia of the hip: a retrospective cohort study. J Child Orthop. 2016;10:179–84.

Hall A, Barker D, Dangerfield P, Osmond C, Taylor J. Small feet and Perthes’ disease. A survey in Liverpool. J Bone Joint Surg Br. 1988;70-B:611–3.

Fabry K, Fabry G, Moens P. Legg-Calvé-Perthes disease in patients under 5 years of age does not always result in a good outcome. Personal experience and meta-analysis of the literature. J Pediatr Orthop Part B. 2003;12:222–7.

Larson AN, Sucato DJ, Herring JA, Adolfsen SE, Kelly DM, Martus JE, et al. A prospective multicenter study of Legg-Calvé-Perthes disease: functional and radiographic outcomes of nonoperative treatment at a mean follow-up of twenty years. J Bone Jt Surg - Ser A. 2012;94:584–92.

Horton DB, Haynes K, Denburg MR, Thacker MM, Rose CD, Putt ME, et al. Oral glucocorticoid use and osteonecrosis in children and adults with chronic inflammatory diseases: a population-based cohort study. BMJ Open. 2017;7.

Tsampalieros A, Lam CKL, Spencer JC, Thayu M, Shults J, Zemel BS, et al. Long-term inflammation and glucocorticoid therapy impair skeletal modeling during growth in childhood crohn disease. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2013;98:3438–45.

Smith FE, Sweet DE, Brunner CM, Davis JS IV. Avascular necrosis in SLE. An apparent predilection for young patients. Ann Rheum Dis. 1976;35:227–32.

Zizic TM, Marcoux C, Hungerford DS, Dansereau JV, Stevens MB. Corticosteroid therapy associated with ischemic necrosis of bone in systemic lupus erythematosus. Am J Med. 1985;79:596–604.

Te Winkel ML, Pieters R, Hop WCJ, De Groot-Kruseman HA, Lequin MH, Van Der Sluis IM, et al. Prospective study on incidence, risk factors, and long-term outcome of osteonecrosis in pediatric acute lymphoblastic leukemia. J Clin Oncol. 2011;29:4143–50.

Loder RT, Starnes T, Dikos G, Aronsson DD. Demographic predictors of severity of stable slipped capital femoral epiphyses. J Bone Jt Surg - Ser A. 2006;88:97–105.

Davis RL, Samora WP, Persinger F, Klingele KE. Treatment of unstable versus stable slipped capital femoral epiphysis using the modified Dunn procedure. J Pediatr Orthop. 2019.

Upasani VV, Birke O, Klingele KE, Millis MB. Iatrogenic hip instability is a devastating complication after the modified Dunn procedure for severe slipped capital femoral epiphysis. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 2017;475:1229–35.

Weigl DM, Becker T, Mercado E, Bar-On E. Percutaneous aspiration and irrigation technique for the treatment of pediatric septic hip: effectiveness and predictive parameters. J Pediatr Orthop Part B. 2016;25:514–9.

Sanpera I, Raluy-Collado D, Sanpera-Iglesias J. Arthroscopy for hip septic arthritis in children. Orthop Traumatol Surg Res. 2016;102:87–9.

Campagnaro JG, Donzelli O, Urso R, Valdiserri L. Treatment of the sequelae of septic osteoarthritis of the hip during pediatric age. Chir Organi Mov. 1992;77:233–45.

Furnes O, Lie SA, Espehaug B, Vollset SE, Engesaeter LB, Havelin LI. Hip disease and the prognosis of total hip replacements: a review of 53 698 primary total hip replacements reported to the norwegian arthroplasty register 1987-99. [Miscellaneous Article]. J Bone Jt Surg - Br Vol. 2001;83-B:579–86.

Amstutz HC, Su EP, Le Duff MJ. Surface arthroplasty in young patients with hip arthritis secondary to childhood disorders. Orthop. Clin. North Am. 2005. p. 223–30.

Roberts CS, Fetto JF. Functional outcome of hip fusion in the young patient: follow-up study of 10 patients. J Arthroplast. 1990;5:89–96.

Milgram JW, Rana NA. Resection arthroplasty for septic arthritis of the hip in ambulatory and nonambulatory adult patients. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 1991;272:181–91.

Goodman DA, Feighan JE, Smith AD, Latimer B, Buly RL, Cooperman DR. Subclinical slipped capital femoral epiphysis. Relationship to osteoarthrosis of the hip. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 1997;79:1489–97.

Amstutz HC, Beaulé PE, Dorey FJ, Le Duff MJ, Campbell PA, Gruen TA. Metal-on-metal hybrid surface arthroplasty: two to six-year follow-up study. J Bone Jt Surg - Ser A. 2004;86:28–39.

Della Valle CJ. Nunley RM. Raterman SJ: Barrack RL. Initial american experience with hip resurfacing following FDA approval. Clin Orthop Relat Res; 2009. p. 72–8.

Stulberg BN, Trier KK, Naughton M, Zadzilka JD. Results and lessons learned from a United States hip resurfacing investigational device exemption trial. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2008;90(Suppl 3):21–6.

McGrory B, Barrack R, Lachiewicz PF, Schmalzried TP, Yates AJ, Watters WC, et al. Modern metal-on-metal hip resurfacing. J. Am. Acad. Orthop. Surg. 2010. p. 306–14.

Kim YH, Kim JS, Park JW, Joo JH. Contemporary total hip arthroplasty with and without cement in patients with osteonecrosis of the femoral head: a concise follow-up, at an average of seventeen years, of a previous report. J Bone Jt Surg - Ser A. 2011;93:1806–10.

Petis S, Howard JL, Lanting BL, Vasarhelyi EM. Surgical approach in primary total hip arthroplasty: anatomy, technique and clinical outcomes. Can. J. Surg. 2015. p. 128–39.

Torchia ME, Klassen RA, Bianco AJ. Total hip arthroplasty with cement in patients less than twenty years old: long-term results. J Bone Jt Surg - Ser A. 1996;78:995–1003.

Kahlenberg CA, Swarup I, Krell EC, Heinz N, Figgie MP. Causes of revision in young patients undergoing total hip arthroplasty. J Arthroplast. 2019 Jul;34(7):1435–40.

Lim S, Park Y. Modular cementless total hip arthroplasty for hip infection sequelae. Orthopedics. 2005;28:s1063–8.

Woodcock J, Larson AN, Mabry TM, Stans AA. Do retained pediatric implants impact later total hip arthroplasty? J Pediatr Orthop. 2013;33:339–44.

Gallazzi E, Morelli I, Peretti G, Zagra L. What is the impact of a previous femoral osteotomy on THA? A systematic review. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 2019;477(5):1176–87.

Kotlarsky P. Developmental dysplasia of the hip: what has changed in the last 20 years? World J Orthop. 2015;6:886.

Kwon MS, Kuskowski M, Mulhall KJ, Macaulay W, Brown TE, Saleh KJ. Does surgical approach affect total hip arthroplasty dislocation rates? Clin Orthop Relat Res. 2006. p. 34–8.

Pallante GD, Statz JM, Milbrandt TA, Trousdale RT. Primary total hip arthroplasty in patients 20 years old and younger. J bone joint Surg am. United States. 2020;102:519–25.

Sanchez-Sotelo J, Trousdale RT, Berry DJ, Cabanela ME. Surgical treatment of developmental dysplasia of the hip in adults: I. nonarthroplasty options. J Am Acad Orthop Surg. 2002;10(5):321–33.

Kunutsor SK, Whitehouse MR, Blom AW, Beswick AD, Team INFORM. Patient-related risk factors for periprosthetic joint infection after total joint arthroplasty: a systematic review and meta-analysis. PLoS One. 2016;11(3):e0150866. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0150866.

Acknowledgements

The authors are very grateful to Professor R. Facchini for having supported the realization of this study.

Funding

None.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

FL conceptualized the study; contributed to data acquisition, analysis and interpretation; drafted the work; contributed to the critical revision of the work; approved the final version; and agreed to be accountable for all aspects of the work in ensuring that questions related to the accuracy or integrity of any part of the work are appropriately investigated and resolved.

IM conceptualized the study; contributed to data acquisition, analysis and interpretation; drafted the work; contributed to the critical revision of the work; approved the final version; and agreed to be accountable for all aspects of the work in ensuring that questions related to the accuracy or integrity of any part of the work are appropriately investigated and resolved. CMS contributed to acquisition and interpretation of study data, approved the final version of the work, and agreed to be accountable for all aspects of the work in ensuring that questions related to the accuracy or integrity of any part of the work are appropriately investigated and resolved. ADG contributed to acquisition and interpretation of study data, approved the final version of the work, and agreed to be accountable for all aspects of the work in ensuring that questions related to the accuracy or integrity of any part of the work are appropriately investigated and resolved. FV conceptualized the study, contributed to data interpretation, approved the final version, and agreed to be accountable for all aspects of the work in ensuring that questions related to the accuracy or integrity of any part of the work are appropriately investigated and resolved. NM conceptualized the study, contributed to data interpretation and to the critical revision of the work, approved the final version, and agreed to be accountable for all aspects of the work in ensuring that questions related to the accuracy or integrity of any part of the work are appropriately investigated and resolved. GMP conceptualized the study, contributed to data acquisition and interpretation, contributed to the critical revision of the work, approved the final version, and agreed to be accountable for all aspects of the work in ensuring that questions related to the accuracy or integrity of any part of the work are appropriately investigated and resolved. DC conceptualized the study, contributed to data acquisition and interpretation, contributed to the critical revision of the work, approved the final version, and agreed to be accountable for all aspects of the work in ensuring that questions related to the accuracy or integrity of any part of the work are appropriately investigated and resolved.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

Case series, retrospective study, not applicable

Consent for publication

Identifying patients’ data absent, not applicable

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/. The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver (http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/) applies to the data made available in this article, unless otherwise stated in a credit line to the data.

About this article

Cite this article

Luceri, F., Morelli, I., Sinicato, C.M. et al. Medium-term outcomes of total hip arthroplasty in juvenile patients. J Orthop Surg Res 15, 476 (2020). https://doi.org/10.1186/s13018-020-01990-2

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s13018-020-01990-2