Abstract

Objective

Approximately 300 mg of calcium a day is provided into infants to maintain the physical development of infants, and 5 to 10% bone loss occurs in women during breastfeeding. Hip fractures are considered the most serious type of osteoporotic fracture. We performed this meta-analysis to investigate the association between breastfeeding and osteoporotic hip fractures.

Material and methods

PubMed and Embase were searched until May 1, 2019, for studies evaluating the relationship between breastfeeding and osteoporotic hip fracture in women. The quality of the included studies was evaluated by the methodological index for non-randomized studies (MINORS). For the dose-response meta-analysis, we used the “generalized least squares for trend estimation” method proposed by Greenland and Longnecker to take into account the correlation with the log RR estimates across the duration of breastfeeding.

Results

Seven studies were moderate or high quality, enrolling a total of 103,898 subjects. The pooled outcomes suggested that breastfeeding can decrease the incidence of osteoporotic hip fracture (RR = 0.64 (95% CI 0.43, 0.95), P = 0.027). Dose-response analysis demonstrated that the incidence of osteoporotic hip fracture decreased with the increase of breastfeeding time. The RR and 95% CI for 3 months, 6 months, 12 months, and 24 months were RR = 0.93, 95% CI 0.88, 0.98; RR = 0.87, 95% CI 0.79, 0.96; RR = 0.79, 95% CI 0.67, 0.92; and RR = 0.76, 95% CI 0.59, 0.98, respectively, whereas no significant relationship was found between them when the duration of breastfeeding time was more than 25 months.

Conclusions

Our meta-analysis demonstrated that the incidence of osteoporotic hip fracture decreased with the extension of breastfeeding time. However, there is no significant relationship between them when the duration of breastfeeding time was more than 25 months.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Osteoporotic fracture has become a common health problem all over the world due to the aging of the population [1]. More than one third of 50-year-old women will suffer from serious osteoporotic fractures in their remaining lifetimes [2], and every 3 s one osteoporotic fracture occurs somewhere in the world. Hip fracture is also known as the last fracture in their remainder lifetimes and is considered the most serious type of osteoporotic fractures due to high morbidity and mortality. The previous study demonstrated that an approximated 20 to 40% of patients with hip fracture will suffer from death in 1 year, and only one in three of these patients can recover their previous functional status [3].

Breastfeeding is an essential reproductive function among females, provides approximately 300 mg of calcium a day into infants to maintain the physical development of infants [4], and results in 5 to 10% bone loss in women during breastfeeding [5]. Besides, they need to provide large amounts of calcium for mineralization of the fetal and neonatal skeleton [6]. Therefore, bone loss in women starts earlier than in men [7], and this may be one reason why osteoporosis occurs in older women far more than in men. Women with severe osteoporosis may suffer from a fragility fracture [8]. However, it is controversial whether breastfeeding can increase the risk of osteoporotic hip fractures, and the possible mechanism is considerably complicated. Some studies demonstrated breastfeeding may contribute to protection against osteoporotic hip fractures [9,10,11,12], and the risk will decrease with the extent of breastfeeding [9, 10, 12]. However, some studies indicated that prolonged breastfeeding time can decrease bone mineral density [13, 14]. Whereas others indicated that breastfeeding was unrelated to osteoporotic hip fracture or bone density in postmenopausal women [15, 16]. What is more, there is insufficient evidence in individual studies to show the relationship between them and express conflicting conclusions.

Therefore, we performed this dose-response meta-analysis to investigate the association between breastfeeding and osteoporotic hip fracture in women, hypothesizing that breastfeeding is associated with lower osteoporotic hip fracture, and to provide a better guiding strategy for clinicians.

Materials and methods

We carried out this meta-analysis according to the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analysis (PRISMA) statement [17] and the Cochrane Collaboration guidelines strictly.

Search strategy

PubMed and Embase were searched until May 1, 2019. Besides, we manually searched the reference lists of all identified relevant publications to find potential studies, without language restrictions. Search terms included the keywords related to osteoporosis, hip, fracture, breastfeeding, and their variants. The Boolean operators were used to combine them.

Study selection and eligibility criteria

Inclusion criteria: (1) the exposure was breastfeeding, (2) the outcome was osteoporotic hip fracture, (3) sample size was more than 100, and (4) the included article provides sufficient data. Exclusion criteria: (1) other types of fractures; (2) hip fracture due to severe trauma; (3) case report, review, commentary, and study just included an abstract; and (4) there was duplicate publication

Data extraction

Data extraction was performed by two reviewers. General characteristics of the patient were extracted from included studies: author, year of publication, study designs, sample size, age, country, diagnostic methods, and adjustment for covariance. Any disagreements were resolved by discussion to reach a consensus. All extracted data were entered into a predefined standardized Excel (Microsoft Corporation, USA) file carefully.

Quality assessment

Two reviewers evaluated the quality of studies by the methodological index for non-randomized studies (MINORS) respectively. The MINORS is a useful tool for assessing the quality of non-randomized studies [18]. This scale contains 12 items. Each index is 2 scores, the total score is 24, and higher scores indicate higher quality.

Statistical analysis

Statistical analyses were performed using R software and STATA 12.0. The association between breastfeeding and osteoporotic hip fracture was expressed as RR with corresponding 95% CIs. P value less than 0.05 was regarded as statistically significant. Statistical heterogeneity was assessed by the I2 statistic; when I2 > 50% and P < 0.1, random effect model was used; if not, fixed effect model was used. Generic inverse variance was used in this meta-analysis. Dose-response analysis was performed using the method described by Greenland and Longnecker [19], which takes into account the correlation with the log RR estimates across the duration of breastfeeding. Only studies providing the cases and cohort size subjects and the RRs could be included in the analysis. The value assigned to each category of breastfeeding month was the median provided by the original study. For the studies not containing a median, we used the midpoint for closed category; when the highest category was open-ended, we assumed the midpoint of the category was set at 1.2 times the lower boundary [20]. We estimated the potential non-linear dose-response relationship in two stages: firstly, a restricted cubic spline model was estimated; secondly, the 2 regression coefficients and the variance matrix within each study were combined. P value for non-linearity was calculated by testing the null hypothesis that the coefficient of the second spline is equal to zero [21].

Results

Search result

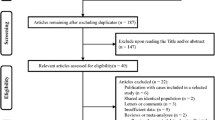

A total of 678 potentially relevant references were founded. Endnote X8 (version 18.0.0.10063) was used to remove 265 duplicate studies. By scanning the titles and abstracts, 404 studies were excluded. After a scan of the full texts, 2 studies were excluded, which merely include one set of data for the follow-up period [22, 23]. Finally, 7 studies were included. Details of the study selection process were shown in Fig. 1.

Study characteristics

Two of the seven were cohort studies [7, 15], and five were case-control studies [10,11,12, 16, 24]. These study sample sizes ranged from 308 to 92,980 subjects, with a total of 103,898 subjects. The main characteristics of the included trials are summarized in Table 1.

Quality assessment

The average score was 17.3 (range, 15–19), suggesting that all the studies were of moderate or high quality. Details of the quality assessment of included studies were shown in Table 2.

Clinical outcomes

Seven studies [7, 10,11,12, 15, 16, 24] provided available data and the pooled outcomes demonstrated that breastfeeding can decrease the incidence of osteoporotic hip fracture (RR = 0.64 (95% CI 0.43, 0.95), P = 0.027, I2 = 69.3%; Fig. 2).

Dose-response analysis

Seven studies [7, 10,11,12, 15, 16, 24] provided continuous data on dose-response meta-analysis. Using a restricted cubic spline model, we observed a non-linear dose-response relationship between the duration of breastfeeding and risk of osteoporotic hip fracture (χ2 test for non-linearity = 9.7 (df = 2), P = 0.0079) and the heterogeneity among studies was not significant (multivariate Cochran Q test for heterogeneity = 19.9 (df = 12), P = 0.069, I2 = 39.6%); the dose-response curve (shown in Fig. 3) indicates that with the increase of breastfeeding time, the risk of osteoporotic hip fracture decreased gradually. With the females without breastfeeding as a reference group, the RR and 95% CI for 3 months, 6 months, 12 months, and 24 months were RR = 0.93, 95% CI 0.88, 0.98; RR = 0.87, 95% CI 0.79, 0.96; RR = 0.79, 95% CI 0.67, 0.92; and RR = 0.76, 95% CI 0.59, 0.98, respectively. When the duration of breastfeeding time was more than 25 months, there was no significant relationship between them.

Discussion

Main findings

This study demonstrated that there was a non-linear relationship between breastfeeding and osteoporotic hip fracture. The risk of osteoporotic hip fracture decreased with the extent of breastfeeding. However, there is no significant relationship between them when the duration of breastfeeding time was more than 25 months.

The association between breastfeeding and bone mineral density (BMD) in older women is complicated; studies in different regions have yielded different conclusions. In a nationwide survey in Korea by Hwang et al., the outcomes indicated that breastfeeding for more than 37 months can decrease the BMD in postmenopausal women [14]. Fox et al. pointed out there was no significant difference in the radius BMD between the women who was breastfeeding with those who were not [25]. Murphy et al. reported that there was no association between BMD and breastfeeding in the hip and spine [26], which is similar to the outcomes of Crandall et al. [15]. The study of Bjørnerem et al. demonstrated that the level of BMD of female breastfeeding for about 20 months or more were similar to those who did not breastfeed at the distal forearm and hip [9]. Besides, both Zhang et al. and Lenora et al. reported that breastfeeding does not significantly reduce BMD [27, 28]. What is more, the study of Melton et al. demonstrated that breastfeeding for more than 8 months was associated with higher BMD at the femur and spine [29]. Chantry et al. point out that compared to women who are not breastfeeding, lactation among adolescent mothers had a higher hip BMD at 20 to 25 years old [30].

It is controversial whether breastfeeding impacts on fractures due to inconsistent breastfeeding time. Bolzetta et al. found that breastfeeding more than 18 months significantly increases the risk of spinal fractures in menopausal women [31], similar to the study of Dursun et al. [32]. But Chan et al. considered that breastfeeding for 24 months or more was protective against vertebral fracture [33]. Bjørnerem et al. point out that there was no significant difference in wrist fracture between the breastfeeding groups and the non-breastfeeding group [7]. Whereas the study of Mallmin et al. demonstrated that the ever breastfeeding group has a lower risk of factors than the never breastfeeding group at the distal forearm [34]. The study of Hwang et al. suggested that prolonged breastfeeding has no significant effect on the incidence of osteoporotic hip fractures [14]. However, Bjørnerem et al. indicated that breastfeeding has no long-term deleterious effect on bone fragility and fractures, even reduced risk for hip fracture in menopausal women [9]. The outcomes of our meta-analysis demonstrated that breastfeeding within 25 months contribute to a reduced risk for osteoporotic hip fractures, when breastfeeding is longer than 25 months, there is no significant relationship between them.

Heterogeneity analysis

Most of the included studies had adjusted for potential confounders and this meta-analysis was restricted to the patients with osteoporotic hip fracture, which were higher homogeneously and selective. However, the pooled results in Fig. 2 had high heterogeneity, so we made further investigation to find the source of heterogeneity. Heterogeneity remains high after the exclusion of each study once a time. Different follow-up time and countries may be the significant source of heterogeneity.

Possible mechanisms

The main factors regulating BMD are Parathyroid hormone-related protein (PTHrP), estrogen, and other markers for bone formation during lactation. The secretion of PTHrP counterbalances bone loss during breastfeeding; PTHrP can stimulate reabsorption of calcium from the maternal skeleton, renal tubular reabsorption of calcium, and indirect suppression of parathyroid hormone (PTH) [6]. Estrogen deficiency will increase skeletal resorption and increase the blood calcium concentration, which increases renal calcium losses [35]. However, the concentration of estrogen increases during breastfeeding, which promotes bone formation to a certain extent [36]. During breastfeeding, there are higher concentrations of PTHrP and estrogen, which is beneficial to the formation of bone mass [4]. In addition, osteocalcin and N-telopeptides are markers for bone formation, which levels increased with prolonged lactation within a certain range [37]. An approximated 6 to 12 months after weaning, the bone density is fully restored [35, 38], which may explain why the incidence of osteoporotic hip fractures has not increased in women after breastfeeding. The exact mechanism of this recovery process is unclear and needs further exploration [4].

Limitations

Although this is the first study to use dose-response analysis to investigate the relationship between osteoporotic hip fracture and breastfeeding, the weakness of this meta-analysis should be considered. (1) There was a great difference in the sample size of included studies, especially the study of Crandall et al. [15], which may affect the accuracy of our results. (2) There may be some potential publication bias due to the limited number of studies included. (3) This meta-analysis has not been registered online in advance. (4) We did not retrieve grey literature, which may affect the accuracy of the conclusions to some extent.

Conclusion

Our meta-analysis demonstrated that there is a non-linear relationship between breastfeeding with osteoporotic hip fracture based on the previous studies. The risk of osteoporotic hip fracture decreased with the increase of breastfeeding time. However, there is no significant relationship between them when the duration of breastfeeding time was more than 25 months.

Availability of data and materials

All data are fully available without restriction.

Abbreviations

- BMD:

-

Bone mineral density

- CI:

-

Confidence interval

- PTH:

-

Parathyroid hormone

- PTHrP:

-

Parathyroid hormone-related protein

- RR:

-

Relative risk

References

Zhao JG, Zeng XT, Wang J, Liu L. Association between calcium or vitamin D supplementation and fracture incidence in community-dwelling older adults: a systematic review and meta-analysis. JAMA. 2017;318(24):2466–82.

Saei Ghare Naz M, Ozgoli G, Aghdashi MA, Salmani F. Prevalence and risk factors of osteoporosis in women referring to the bone densitometry academic center in Urmia, Iran. Glob J Health Sci. 2015;8(7):135–45.

Guzon-Illescas O, Perez Fernandez E, Crespi Villarias N, Quiros Donate FJ, Pena M, Alonso-Blas C, Garcia-Vadillo A, Mazzucchelli R. Mortality after osteoporotic hip fracture: incidence, trends, and associated factors. J Orthop Surg Res. 2019;14(1):203.

Kovacs CS. Calcium and bone metabolism disorders during pregnancy and lactation. Endocrinol Metab Clin North Am. 2011;40(4):795–826.

Kalkwarf HJ. Hormonal and dietary regulation of changes in bone density during lactation and after weaning in women. J Mammary Gland Biol Neoplasia. 1999;4(3):319–29.

Kovacs CS. Calcium and bone metabolism during pregnancy and lactation. J Mammary Gland Biol Neoplasia. 2005;10(2):105–18.

Bjørnerem A, Ahmed LA, Joakimsen RM, Berntsen GK, Fonnebo V, Jorgensen L, Oian P, Seeman E, Straume B. A prospective study of sex steroids, sex hormone-binding globulin, and non-vertebral fractures in women and men: the Trømso Study. Eur J Endocrinol. 2007;157(1):119–25.

Miyamoto T, Miyakoshi K, Sato Y, Kasuga Y, Ikenoue S, Miyamoto K, Nishiwaki Y, Tanaka M, Nakamura M, Matsumoto M. Changes in bone metabolic profile associated with pregnancy or lactation. Sci Rep. 2019;9(1):6787.

Bjørnerem A, Ahmed LA, Jorgensen L, Stormer J, Joakimsen RM. Breastfeeding protects against hip fracture in postmenopausal women: the Trømso study. J Bone Miner Res. 2011;26(12):2843–50.

Huo D, Lauderdale DS, Li L. Influence of reproductive factors on hip fracture risk in Chinese women. Osteoporos Int. 2003;14(8):694–700.

Michaelsson K, Baron JA, Farahmand BY, Ljunghall S. Influence of parity and lactation on hip fracture risk. Am J Epidemiol. 2001;153(12):1166–72.

Cumming RG, Klineberg RJ. Breastfeeding and other reproductive factors and the risk of hip fractures in elderly women. Int J Epidemiol. 1993;22(4):684–91.

Tsvetov G, Levy S, Benbassat C, Shraga-Slutzky I, Hirsch D. Influence of number of deliveries and total breast-feeding time on bone mineral density in premenopausal and young postmenopausal women. Maturitas. 2014;77(3):249–54.

Hwang IR, Choi YK, Lee WK, Kim JG, Lee IK, Kim SW, Park KG. Association between prolonged breastfeeding and bone mineral density and osteoporosis in postmenopausal women: KNHANES 2010-2011. Osteoporos Int. 2016;27(1):257–65.

Crandall CJ, Liu J, Cauley J, Newcomb PA, Manson JE, Vitolins MZ, Jacobson LT, Rykman KK, Stefanick ML. Associations of parity, breastfeeding, and fractures in the Women’s Health Observational Study. Obstet Gynecol. 2017;130(1):171–80.

Hoffman S, Grisso JA, Kelsey JL, Gammon MD, O'Brien LA. Parity, lactation and hip fracture. Osteoporos Int. 1993;3(4):171–6.

Moher D, Liberati A, Tetzlaff J, Altman DG. Preferred reporting items for systematic reviews and meta-analyses: the PRISMA statement. Int J Surg. 2010;8(5):336–41.

Slim K, Nini E, Forestier D, Kwiatkowski F, Panis Y, Chipponi J. Methodological index for non-randomized studies (minors): development and validation of a new instrument. ANZ J Surg. 2003;73(9):712–6.

Greenland S, Longnecker MP. Methods for trend estimation from summarized dose-response data, with applications to meta-analysis. Am J Epidemiol. 1992;135(11):1301–9.

Shao C, Tang H, Zhao W, He J. Nut intake and stroke risk: a dose-response meta-analysis of prospective cohort studies. Sci Rep. 2016;6:30394.

Orsini N, Li R, Wolk A, Khudyakov P, Spiegelman D. Meta-analysis for linear and nonlinear dose-response relations: examples, an evaluation of approximations, and software. Am J Epidemiol. 2012;175(1):66–73.

Johnell O, Gullberg B, Kanis JA, Allander E, Elffors L, Dequeker J, Dilsen G, Gennari C, Lopes Vaz A, Lyritis G, et al. Risk factors for hip fracture in European women: the MEDOS Study. J Bone Miner Res. 1995;10(11):1802–15.

Clark P, de la Pena F, Gomez Garcia F, Orozco JA, Tugwell P. Risk factors for osteoporotic hip fractures in Mexicans. Arch Med Res. 1998;29(3):253–7.

Alderman BW, Weiss NS, Daling JR, Ure CL, Ballard JH. Reproductive history and postmenopausal risk of hip and forearm fracture. American journal of epidemiology. 1986;124(2):262–7.

Fox KM, Magaziner J, Sherwin R, Scott JC, Plato CC, Nevitt M, Cummings S. Reproductive correlates of bone mass in elderly women. Study of Osteoporotic Fractures Research Group. J Bone Miner Res. 1993;8(8):901–8.

Murphy S, Khaw KT, May H, Compston JE. Parity and bone mineral density in middle-aged women. Osteoporos Int. 1994;4(3):162–6.

Lenora J, Lekamwasam S, Karlsson MK. Effects of multiparity and prolonged breast-feeding on maternal bone mineral density: a community-based cross-sectional study. BMC Womens Health. 2009;9:19.

Zhang YY, Liu PY, Deng HW. The impact of reproductive and menstrual history on bone mineral density in Chinese women. J Clin Densitom. 2003;6(3):289–96.

Melton LJ 3rd, Bryant SC, Wahner HW, O'Fallon WM, Malkasian GD, Judd HL, Riggs BL. Influence of breastfeeding and other reproductive factors on bone mass later in life. Osteoporos Int. 1993;3(2):76–83.

Chantry CJ, Auinger P, Byrd RS. Lactation among adolescent mothers and subsequent bone mineral density. Arch Pediatr Adolesc Med. 2004;158(7):650–6.

Bolzetta F, Veronese N, De Rui M, Berton L, Carraro S, Pizzato S, Girotti G, De Ronch I, Manzato E, Coin A, et al. Duration of breastfeeding as a risk factor for vertebral fractures. Bone. 2014;68:41–5.

Dursun N, Akin S, Dursun E, Sade I, Korkusuz F. Influence of duration of total breast-feeding on bone mineral density in a Turkish population: does the priority of risk factors differ from society to society? Osteoporos Int. 2006;17(5):651–5.

Chan HH, Lau EM, Woo J, Lin F, Sham A, Leung PC. Dietary calcium intake, physical activity and the risk of vertebral fracture in Chinese. Osteoporos Int. 1996;6(3):228–32.

Mallmin H, Ljunghall S, Persson I, Bergstrom R. Risk factors for fractures of the distal forearm: a population-based case-control study. Osteoporos Int. 1994;4(6):298–304.

Kovacs CS, Kronenberg HM. Maternal-fetal calcium and bone metabolism during pregnancy, puerperium, and lactation. Endocr Rev. 1997;18(6):832–72.

Kovacs CS. Maternal Mineral and Bone Metabolism During Pregnancy, Lactation, and Post-Weaning Recovery. Physiol Rev. 2016;96(2):449–547.

Sowers M, Eyre D, Hollis BW, Randolph JF, Shapiro B, Jannausch ML, Crutchfield M. Biochemical markers of bone turnover in lactating and nonlactating postpartum women. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 1995;80(7):2210–6.

Polatti F, Capuzzo E, Viazzo F, Colleoni R, Klersy C. Bone mineral changes during and after lactation. Obstet Gynecol. 1999;94(1):52–6.

Acknowledgements

We thank the authors of the included studies for their help.

Funding

No fund support

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

HXX, JZB, XBZ, and GQN conceived of the design of the study. HXX, ZCZ, GSH, and QBZ participated in the literature search, study selection, data extraction, and quality assessment. QZ and JZB performed the statistical analysis. JZB and QZ finished the manuscript. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

This article does not contain any studies with human participants or animals performed by any of the authors

Consent for publication

Not applicable

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made. The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver (http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/) applies to the data made available in this article, unless otherwise stated.

About this article

Cite this article

Xiao, H., Zhou, Q., Niu, G. et al. Association between breastfeeding and osteoporotic hip fracture in women: a dose-response meta-analysis. J Orthop Surg Res 15, 15 (2020). https://doi.org/10.1186/s13018-019-1541-y

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s13018-019-1541-y