Abstract

Background

Artificial intelligence (AI) is gaining traction in medicine and surgery. AI-based applications can offer tools to examine high-volume data to inform predictive analytics that supports complex decision-making processes. Time-sensitive trauma and emergency contexts are often challenging. The study aims to investigate trauma and emergency surgeons’ knowledge and perception of using AI-based tools in clinical decision-making processes.

Methods

An online survey grounded on literature regarding AI-enabled surgical decision-making aids was created by a multidisciplinary committee and endorsed by the World Society of Emergency Surgery (WSES). The survey was advertised to 917 WSES members through the society’s website and Twitter profile.

Results

650 surgeons from 71 countries in five continents participated in the survey. Results depict the presence of technology enthusiasts and skeptics and surgeons' preference toward more classical decision-making aids like clinical guidelines, traditional training, and the support of their multidisciplinary colleagues. A lack of knowledge about several AI-related aspects emerges and is associated with mistrust.

Discussion

The trauma and emergency surgical community is divided into those who firmly believe in the potential of AI and those who do not understand or trust AI-enabled surgical decision-making aids. Academic societies and surgical training programs should promote a foundational, working knowledge of clinical AI.

Similar content being viewed by others

Background

Artificial intelligence (AI) is defined as the development of algorithms that give machines the ability to act with human-like rationality in complex tasks, such as problem-solving and decision-making, and is poised to reshape medicine and surgery broadly [1].

Diagnostic and judgment errors are the second leading cause of preventable harm [2]. Decision-making is one of the most challenging and crucial tasks performed by trauma and emergency surgeons, where time constraints and high cognitive loads from high volumes of information demand reliance on cognitive shortcuts, leading to mistakes and preventable patient harm [3].

In recent years, decision support systems based on AI algorithms are receiving considerable attention in the literature [4,5,6]. In contrast to human cognitive capacities, AI can be used to examine high-complexity and high-volume data for predictive analytics to augment the precision of complex decision-making processes. Nonetheless, deploying medical AI systems in routine trauma and emergency surgery care presents a critical yet largely unfulfilled opportunity as the medical AI community steers the complex ethical, technical, and human-centered challenges required for safe and adequate translation [7,8,9,10]. Experienced surgeons are appropriately cautious of enthusiastic, novel solutions that are unsubstantiated by academic rigor and evidence of performance advantages in clinical settings [8]. Even when AI accurately predicts clinical outcomes hours or days in advance, its application in trauma and emergency surgery will remain marginal until the deployment proves trust in the accuracy and the lack of bias of the model, addresses target risk-sensitive decisions, and integrates with clinical workflows [11, 12].

The recently published artificial intelligence in Emergency and Trauma Surgery (ARIES) survey, endorsed by the World Society of Emergency Surgery (WSES) evaluated the knowledge, attitude, and practices in the application of AI in the emergency setting among international acute care and emergency surgeons. The investigation revealed how the implementation of AI in the emergency and trauma setting is highly anticipated but still in an early phase, with trauma and emergency surgeons enthusiastic about being involved [13].

Starting from these premises and research gaps, this article aims to assess surgeons’ understanding and knowledge about the role of new technologies like AI in clinical decision-making by employing an international survey endorsed by the WSES.

Methods

Design and setting

The exploratory study of the international trauma and emergency surgeons’ community used a population-based online questionnaire to gather demographic, knowledge, and practice-based information regarding the adoption of new technological tools to support clinical decision-making. The online questionnaire was generated in English through Google Forms [14, 15], and followed the Checklist for Reporting Results of Internet E-Surveys (CHERRIES) [16].

A steering committee within the WSES was appointed, involving a multidisciplinary panel of academics and practitioners in the fields of trauma and emergency surgery, healthcare management and policies, innovation, business and medical ethics, information technology, law, and organization science. No Institutional Review Board (IRB) approval was required. Starting from a review of the literature, a research protocol was conceived and shared by the principal investigators (LC and FDM) with the steering committee. The protocol was peer-reviewed and published [17]. The leading references to create the protocol and the survey structure were gathered from Dal Mas et al. [18], Loftus et al. [19, 20], Cobianchi et al. [21], Venkatesh et al. [22], and Bashshur, Shannon and Sapci [23]. Before the initiative's official launch, the research protocol and the online survey were reviewed by the steering committee and filled in by a sample of surgeons to avoid mistakes.

The poll was made available at the end of November 2021 and was open until the middle of August 2022. All 917 WSES members received an e-mail invitation to participate in the survey. The initiative was also shared on the society's website and Twitter account. Additionally, the members of the Team Dynamics Study Group [14, 15] were also invited via e-mail. Four e-mail reminders were sent. WSES membership was not required to answer the survey. Still, it may be assumed that the vast majority of the participants come from the 917 WSES members to whom the research initiative was publicized, yielding an approximate 70% response rate.

The invitation e-mail included comprehensive details on the initiative's goals and rationale, the anticipated time frame (about 10 min), and the option to join the Team Dynamics Study Group to carry out additional research and disseminate the results. The identities of the participants were kept secret. Additionally, the identity of the investigators and the research protocol were kept private.

Survey

The first group of questions aimed at understanding the participants’ features. The questions’ structure and list were derived from the previous Team Dynamics investigation [14, 15]. Surgeons were asked to disclose their gender, years of experience in trauma/emergency surgery, type of institution (academic versus non-academic), the country in which they work, role, eventual participation within a trauma team (institutionalized or not, and of which type), the kind of trauma leader, the educational training attended, and the eventual presence of diverse team members.

The second group of questions investigated the decision aids as reported by the surgical literature [18,19,20], by assessing the surgeons’ perception of 11 items using a 5-point Likert scale.

The third group of questions concerned the perceived challenges that surgeons need to face when making clinical decisions, assessing 13 items gathered from Loftus and colleagues [20] using a 5-point Likert scale.

The fourth section of the questionnaire aimed at assessing the surgeons’ feelings about AI by asking them if they were familiar with the term AI, their understanding of it through an open question, and the perceived importance of AI in surgery at the present time and in a five-year horizon. One last question aimed to assess the perceived benefits [21, 22] of the application of AI in surgery.

The survey’s questions related to clinical decision-making through new technological aids are reported in Appendix 1.

Statistical analysis

The statistical analysis was conducted using the software R (RStudio 2022.07.0 + 548 "Spotted Wakerobin" Release) [24].

Manual coding was also employed concerning the qualitative questions. Surgeons were required to express their understanding of AI through an open question. Results were manually coded by two researchers (LC and FDM), who rated each statement as concordant, discordant, or inconclusive, following the analysis of Woltz et al. [25] and Cobianchi et al. [14].

Results

Participants

650 surgeons responded to the questionnaire. Located on five continents, participants hailed from 71 different nations. The sample, however, was not evenly dispersed, with the majority of surgeons coming from Europe (477, or 73%), particularly Italy (251, or 39%). 465 responders (72%) were from the 10 nations with the most participants overall.

118 female surgeons (18%), 531 male surgeons (82%), and one person who would rather remain anonymous made up the sample. Surgeons' years of experience in the field ranged from 1 to 35, with a mean of 12. The majority of participants (499, or 77% of the sample) were from academic institutions, and 540 of them declared to be part of a formally-established emergency surgery team (83%). Although there were a variety of roles indicated, senior consultants made up the bulk of surgeons (233, or 36%). Department heads made up 114 (18%) of the sample.

Table 1 presents descriptive statistics about the individuals and institutions that participated in the study, whereas Table 2 reports some information about the number of respondents according to their locations.

Clinical decision-making facilitators

Surgeons were given a list of 11 items referred to clinical decision-making facilitators to be rated on a 5-point Likert scale according to their perceived importance. Clinicians underlined the importance of training, clinical guidelines, and multidisciplinary committees and meetings, with a mean of over 4 out of 5. Interestingly, the most modern tools (namely, risk stratification by additive scores using static variable thresholds, machine learning and artificial intelligence, regression modeling and calculations—with 3.87, 3.56, and 3.49, respectively) received the lowest scores, with machine learning and artificial intelligence recording the highest standard deviation (1.07). The following Table 3 reports the results.

The responses given to the item “Machine Learning and Artificial Intelligence” were analyzed by dividing the sample by institution, position held, and country. Interestingly, the institution (academic or non-academic) and the role did not show any significant difference. Major differences emerged when analyzing countries, with some of them (like Argentina) showing a high mean (4.5) and a low standard deviation (0.548), and others (like Switzerland) a very low mean (2.6) and a high standard deviation (0.89). Such results are reported in the following Table 4.

Moreover, the same responses were analyzed by considering the institution, position, and country simultaneously. Although numbers become smaller, some interesting findings emerge. For instance, all senior consultants belonging to Malaysian academic institutions firmly believed in AI, with all of them giving a rate of 5/5, compared to division chiefs working in the USA, who scored the item 2.5 with a standard deviation of 1.05. Despite being digital natives, residents do not appear in the top positions. Results are depicted in the following Table 5.

Challenges in clinical decision-making

Surgeons were asked to rate 13 items regarding the challenges that could arise when engaging in clinical decision-making. The items were adapted from Loftus et al. [20].

Results underline a perceived misalignment between the actual clinical scenario and the independent assessment, the lack of complete data availability, the risk of expecting specific outcomes grounded on inaccurate data, the presence of bias derived from the most recent experiences, and the possibility of making mistakes all along the clinical journey. Interestingly, surgeons rated the potential support granted by new technologies like AI as the lowest item (with a mean of 3.10 and the highest standard deviation of 1.14).

Findings are reported in the following Table 6.

Knowledge and understanding of AI

Surgeons were asked if they were familiar with the term AI. 451 out of 650 participants (69% of the sample) declared they were familiar with the term, while 199 (31%) admitted they were not.

The following question required surgeons to write their understanding of AI applied to surgery. Each given statement was rated by the two principal investigators (LC and FDM) as concordant, discordant, or inconclusive.

To be rated as concordant, definitions needed to somehow stress the capability of the machine to mimic human intelligence or, at least, to express the aims and potential of AI applied to surgical practice or its technological functioning. Only 112 surgeons (17% of the sample) provided a statement that fitted the criterion. 178 participants (27% of the sample) gave responses that were incomplete, showing only a partial view of the phenomenon, being so rated as inconclusive. The remaining 360 surgeons (55% of the participants) gave answers that were not fitting the concept of AI, its aims, and its potential. Most of these participants declared they had no idea about what AI could entail in surgical practice.

The following Table 7 reports some examples of answers that were rated as concordant, inconclusive, and discordant [14, 25].

The statements were also analyzed according to different keys, namely, the fact that they recalled the idea of AI supporting clinical decision-making and of learning/training, and the eventual other technologies linked to AI. Most surgeons (409, 63% of the sample) mentioned the impact on clinical decision-making, and 57 (9%) recalled the potential of AI for surgical training. Among the most cited technologies that may be linked with AI, there are Big Data (mentioned by 130 participants – 20% of the sample) and new technologies in general terms (107, 16%).

Table 8 highlights such results.

The potential of AI today and tomorrow

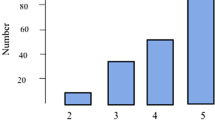

Surgeons were asked to express their opinion about the importance of AI-based applications to support clinical decision-making at the current time and on a five-year horizon, using a 5-point Likert scale.

Participants rated the importance today with a mean of 3.06 out of 5 and a standard deviation of 1.1. In the future, the sample rated the importance as 3.88 as an average with a standard deviation of 0.97.

The goals of AI

One last question referred to the perceived goals and benefits of AI-based in supporting clinical decision-making. Five items needed to be rated on a 5-point Likert scale.

Interestingly, surgeons rated all five items as equally relevant (ranging from a mean score of 3.51 to 3.78). The item with the highest score sees AI as a support tool to validate decisions that clinicians would make anyway.

The following Table 9 reports the results.

Discussion

The results of our survey are in line with previous studies [13], with trauma and emergency surgeons showing interest in AI but still having several doubts and concerns about its actual application and potential as a decision-making aid.

When enquired about the most effective tools to support clinical decision-making, surgeons declare to rely more on training, clinical guidelines, and the support of their multidisciplinary staff and colleagues. Interestingly, these three items represent central and “classical” elements in the trauma and emergency surgery context [14] and in the action of the leading scientific societies like the WSES, which promotes training modules for both physicians and nurses [26], clinical guidelines covering several aspects of the clinical profession [27], and studies on multidisciplinary team dynamics [14, 15]. AI and Machine Learning tools got one of the lowest rates (3.56), with the highest standard deviation (1.07). The broad standard deviation interval may represent a gap in the surgical community, with some surgeons firmly believing in the potential of such new technologies and others still having severe concerns about their practical application.

Interestingly, while no significant differences emerge when considering the institution and the position held, geographical differences occur in the sample, with some countries giving higher scores than others. It would be interesting to investigate further while such differences emerge, for instance, in terms of cultural mindset, training opportunities, availability of technology or tech partners, and presence of technological surgical leaders or ambassadors. Moreover, when analyzing the sample under different lenses simultaneously (institution, role, and country), residents do not appear to be technology enthusiasts and believers, despite their younger age and the definition of digital natives.

When considering the decision-making process dynamics, trauma and emergency surgeons underline the need for sound decision aids. Indeed, the most rated elements refer to the potential gap between reality and the surgeon's initial assessment and the lack of accurate data. Even in this case, most respondents did not believe that AI offers valuable support for decision-making. Like in the case of decision aids, the contribution of AI to decision-making got the highest standard deviation, depicting the two extreme views, with enthusiastic adopters in contrast with skeptics.

Regarding the knowledge about AI, while most surgeons declare to be familiar with the concept of AI, many exhibited only a partial understanding of AI. Interestingly, many surgeons recall big data technology, and some associate AI primarily with robotics. While robotic surgery may represent one promising application of AI in surgical science [13, 28, 29], AI in its current state offers sound decision-making support, like in the case of the POTTER algorithm as an emergency surgery risk calculator [5, 6].

The current general skepticism of trauma and emergency surgeons about AI is also confirmed by the given rate on the relevance of AI-based tools for decision-making as they appear today, with a mean of 3.06. One more time, a high standard deviation interval depicts divergent opinions and beliefs in the surgical community. Still, the future looks brighter, with a higher perceived relevance on a five-year horizon.

The same picture and the divergent trust in using AI-based decision tools emerge in the question about the goals and benefits. Interestingly, the degree of technology acceptance appears generally low, with surgeons being rather skeptical when it comes to AI ensuring better support and outcomes than traditional tools. Such a low degree of acceptance opens up new research avenues to investigate the main concerns in the practical adoption of AI or the ethical bias connected to it. In such a perspective, one primary concern may reside in the lack of technical knowledge regarding AI, which emerges from several questions, especially that on the understanding of AI. Moreover, when enquired about legal responsibility (a topic to which medical doctors are particularly sensitive), surgeons modestly rate the need to share their legal responsibility with either the manufacturer, those in charge of maintenance, or the data manager, and so the need to rethink the informed written consent when new technologies are involved.

Limitations

Although our survey got a reasonably high response rate and 650 participants (approximately 70%), the sample is not equally distributed geographically. Indeed, most participants work in Europe and, more specifically, in Italy. The specific situation of the Italian and European contexts, including the actual access to AI-based technology and the medical education related to it, may have biased some of our results. Our limitations, along with the international community's perceived interest in AI [13], may stimulate new in-depth studies and investigations.

Conclusion

In concluding our work, we return to the premises and research gaps that inspired it. AI-based applications are gaining traction in surgery as decision-making aids, and the surgical community is showing interest in them. Trauma and emergency contexts are often challenging, and surgeons perceive the need for sound decision-making tools.

Our results underline how the emergency surgical community seems to include surgeons who strongly believe in the potential contribution of AI technology and who may act as enthusiastic early adopters [19] and those who are reluctant, feeling more comfortable relying upon more classical aids like guidelines, traditional training, and multidisciplinary groups’ support. Some countries seem to have greater comprehension and trust of AI-based tools. Younger surgeons, who some presume to be keener on using new technologies, do not appear to have greater trust or understanding of AI compared with mid-career and senior surgeons.

Given the potential of AI in clinical practice [7, 20, 30] and the speed of development, the role of scientific societies like the WSES and surgical training programs are crucial to expanding knowledge regarding AI-enabled decision aids, disseminate new approaches, and encompass them in training modules and clinical guidelines, to bridge the gaps between technology enthusiasts and those who misunderstand and mistrust AI. In addition, AI-enabled decision aids in surgery should seek to gain the trust of surgeons by establishing transparency and by demonstrating performance advantages that improve patient care.

Availability of data and materials

The datasets used and/or analyzed during the current study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

Change history

23 March 2023

A Correction to this paper has been published: https://doi.org/10.1186/s13017-023-00493-9

Abbreviations

- AI:

-

Artificial intelligence

- WSES:

-

World society of emergency surgery

- CHERRIES:

-

Checklist for reporting results of internet e-surveys

- IRB:

-

Institutional review board

- SD:

-

Standard deviation

References

Rajpurkar P, Chen E, Banerjee O, Topol EJ. AI in health and medicine. Nat Med. 2022;28(1):31–8.

Healey MA, Shackford SR, Osler TM, Rogers FB, Burns E. Complications in surgical patients. Arch Surg. 2002;137(5):611–8.

Litvin A, Korenev S, Rumovskaya S, Sartelli M, Baiocchi G, Biffl WL, et al. WSES project on decision support systems based on artificial neural networks in emergency surgery. World J Emerg Surg. 2021;16(1):50.

Loftus TJ, Vlaar APJ, Hung AJ, Bihorac A, Dennis BM, Juillard C, et al. Executive summary of the artificial intelligence in surgery series. Surgery. 2022;171(5):1435–9.

Bertsimas D, Dunn J, Velmahos GC, Kaafarani HMA. Surgical Risk Is Not Linear: Derivation and Validation of a Novel, User-friendly, and Machine-learning-based Predictive OpTimal Trees in Emergency Surgery Risk (POTTER) Calculator. Ann Surg [Internet]. 2018;268(4). https://journals.lww.com/annalsofsurgery/Fulltext/2018/10000/Surgical_Risk_Is_Not_Linear__Derivation_and.4.aspx

Maurer LR, Bertsimas D, Bouardi HT, El Hechi M, El Moheb M, Giannoutsou K, et al. Trauma outcome predictor: An artificial intelligence interactive smartphone tool to predict outcomes in trauma patients. J Trauma Acute Care Surg [Internet]. 2021;91(1). https://journals.lww.com/jtrauma/Fulltext/2021/07000/Trauma_outcome_predictor__An_artificial.15.aspx

Johnson-Mann CN, Loftus TJ, Bihorac A. Equity and artificial intelligence in surgical care. JAMA Surg. 2021;156(6):509.

Balch J, Upchurch GR, Bihorac A, Loftus TJ. Bridging the artificial intelligence valley of death in surgical decision-making. Surgery. 2021;169(4):746–8.

Loftus TJ, Upchurch GR, Bihorac A. Building an artificial intelligence-competent surgical workforce. JAMA Surg. 2021;156(6):511.

Ingraham NE, Jones EK, King S, Dries J, Phillips M, Loftus T, et al. Re-Aiming Equity Evaluation in Clinical Decision Support: A Scoping Review of Equity Assessments in Surgical Decision Support Systems. Ann Surg. 2022 Aug;Publish Ah(612).

Loftus TJ, Tighe PJ, Ozrazgat-Baslanti T, Davis JP, Ruppert MM, Ren Y, et al. Ideal algorithms in healthcare: explainable, dynamic, precise, autonomous, fair, and reproducible. In: Lu HH-S (ed.) PLOS Digit Heal. 2022;1(1):e0000006.

Loftus TJ, Shickel B, Ruppert MM, Balch JA, Ozrazgat-Baslanti T, Tighe PJ, et al. Uncertainty-aware deep learning in healthcare: a scoping review. In: Lai Y (ed.) PLOS Digit Heal. 2022;1(8):e0000085.

De Simone B, Abu-Zidan FM, Gumbs AA, Chouillard E, Di Saverio S, Sartelli M, et al. Knowledge, attitude, and practice of artificial intelligence in emergency and trauma surgery, the ARIES project: an international web-based survey. World J Emerg Surg. 2022;17(1):10.

Cobianchi L, Dal Mas F, Massaro M, Fugazzola P, Coccolini F, Kluger Y, et al. Team dynamics in emergency surgery teams: results from a first international survey. World J Emerg Surg. 2021;16:47. https://doi.org/10.1186/s13017-021-00389-6

Cobianchi L, Dal Mas F, Massaro M, Biffl W, Catena F, Coccolini F, et al. Diversity and ethics in trauma and acute care surgery teams: results from an international survey. World J Emerg Surg. 2022;17(1):44. https://doi.org/10.1186/s13017-022-00446-8.

Eysenbach G. Improving the quality of web surveys: the checklist for reporting results of internet E-surveys (CHERRIES). J Med Internet Res. 2004;6(3):1–6.

Cobianchi L, Dal Mas F, Catena F, Ansaloni A. Artificial intelligence and clinical decision-making in emergency surgery. A research protocol. In: Sousa MJ, Kumar PS, Dal Mas F, Sousa S (eds.) Advancements in artificial intelligence in the service sector. London: Routledge; 2023.

DalMas F, Garcia-Perez A, Sousa MJ, LopesdaCosta R, Cobianchi L. Knowledge translation in the healthcare sector. A structured literature review. Electron J Knowl Manag. 2020;18(3):198–211. https://doi.org/10.34190/EJKM.18.03.001

Loftus TJ, Filiberto AC, Balch J, Ayzengart AL, Tighe PJ, Rashidi P, et al. Intelligent, autonomous machines in surgery. J Surg Res. 2020;253:92–9. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jss.2020.03.046.

Loftus TJ, Tighe PJ, Filiberto AC, Efron PA, Brakenridge SC, Mohr AM, et al. Artificial intelligence and surgical decision-making. JAMA Surg. 2020;155(2):148–58.

Cobianchi L, Verde JM, Loftus TJ, Piccolo D, Dal Mas F, Mascagni P, et al. Artificial Intelligence and Surgery: Ethical Dilemmas and Open Issues. J Am Coll Surg. 2022;235(2):268–75. https://journals.lww.com/journalacs/Fulltext/9900/Artificial_Intelligence_and_Surgery__Ethical.215.aspx

Venkatesh V, Morris M, Davis GB, Davis FD. User acceptance of information technology: toward a unified view. Mis Q. 2003;27(3):425–78.

Bashshur R, Shannon G, Krupinski E, Grigsby J. The taxonomy of telemedicine. Telemed J e-health Off J Am Telemed Assoc. 2011;17(6):484–94.

R Development Core Team. The R Manuals [Internet]. R. 2021 [cited 2021 Mar 12]. https://cran.r-project.org/manuals.html

Woltz S, Krijnen P, Pieterse AH, Schipper IB. Surgeons’ perspective on shared decision making in trauma surgery. A national survey. Patient Educ Couns. 2018;101(10):1748–52. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.pec.2018.06.002.

World Society of Emergency Surgery. Wses courses [Internet]. Courses for physicians and nurses. 2022 [cited 2022 Oct 4]. https://www.wses.org.uk/courses

World Society of Emergency Surgery. Wses guidelines [Internet]. WSES Guidelines. 2022 [cited 2022 Oct 4]. https://www.wses.org.uk/guidelines

McBride KE, Steffens D, Duncan K, Bannon PG, Solomon MJ. Knowledge and attitudes of theatre staff prior to the implementation of robotic-assisted surgery in the public sector. PLoS One. 2019;14(3):e0213840. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0213840.

O’Sullivan S, Nevejans N, Allen C, Blyth A, Leonard S, Pagallo U, et al. Legal, regulatory, and ethical frameworks for development of standards in artificial intelligence (AI) and autonomous robotic surgery. Int J Med Robot Comput Assist Surg. 2019;15(1):1–12.

Byerly S, Maurer LR, Mantero A, Naar L, An G, Kaafarani HMA. Machine learning and artificial intelligence for surgical decision making. Surg Infect (Larchmt). 2021;22(6):626–34. https://doi.org/10.1089/sur.2021.007.

Acknowledgements

Please see the list of the Team Dynamics Study Group members.

Kenneth Lyle Abbott1, Abubaker Abdelmalik2, Nebyou Seyoum Abebe3, Fikri Abu-Zidan4, Yousif Abdallah Yousif Adam5, Harissou Adamou6, Dmitry Mikhailovich Adamovich7, Ferdinando Agresta8, antonino Agrusa9, Emrah Akin10, Mario Alessiani11, Henrique Alexandrino12, Syed Muhammad Ali13, Vasilescu Alin Mihai14, Pedro Miguel Almeida15, Mohammed Mohammed Al-Shehari16, Michele Altomare17, Francesco Amico18, Michele Ammendola19, Jacopo Andreuccetti20, Elissavet Anestiadou 21, Peter Angelos22, Alfredo Annicchiarico23, Amedeo Antonelli24, Daniel Aparicio-Sanchez25, antonella Ardito26, Giulio Argenio27, Catherine Claude Arvieux28, Ingolf Harald Askevold29, Boyko Tchavdarov Atanasov30, Goran Augustin31, Selmy Sabry Awad32, Giulia Bacchiocchi 33, Carlo Bagnoli34, Hany Bahouth35, Efstratia Baili36, Lovenish Bains37, Gian Luca Baiocchi38, Miklosh Bala39, Carmen Balagué 40, Dimitrios Balalis41, Edoardo Baldini42, oussama Baraket43, Suman Baral44, Mirko Barone45, Alberto Gonzãlez Barranquero46, Jorge Arturo Barreras47, Gary Alan Bass48, Zulfu Bayhan49, Giovanni Bellanova50, Offir Ben-Ishay 51, Fabrizio Bert52, Valentina Bianchi 53, Helena Biancuzzi54, Chiara Bidoli55, Raluca Bievel Radulescu56, Mark Brian Bignell57, Alan Biloslavo58, Roberto Bini59, Daniele Bissacco60, Paoll Boati61, Guillaume Boddaert62, Branko Bogdanic63, Cristina Bombardini64, Luigi Bonavina65, Luca Bonomo66, Andrea Bottari67, Konstantinos Bouliaris68, Gioia Brachini69, Antonio Brillantino70, Giuseppe Brisinda71, Maloni Mamada Bulanauca72, Luis Antonio Buonomo73, Jakob Burcharth74, Salvatore Buscemi75, Francesca Calabretto76, Giacomo Calini77, Valentin Calu78, Fabio Cesare Campanile79, Riccardo Campo Dall’Orto80, Andrea Campos-Serra81, Stefano Campostrini82, Recayi Capoglu83, Joao Miguel Carvas84, Marco Cascella85, Gianmaria Casoni Pattacini86, Valerio Celentano87, Danilo Corrado Centonze88, Marco Ceresoli89, Dimitrios Chatzipetris90, Antonella Chessa91, Maria Michela Chiarello92, Mircea Chirica93, Serge Chooklin94, Christos Chouliaras95, Sharfuddin Chowdhury96, Pasquale Cianci97, Nicola Cillara98, Stefania Cimbanassi99, Stefano Piero Bernardo Cioffi100, Elif Colak101, Enrique Colás Ruiz102, Luigi Conti103, Alessandro Coppola104, Tiago Correia De Sa105, Silvia Dantas Costa106, Valerio Cozza107, Giuseppe Curro’108, Kirsten Felicia Ann-Sophie Aimee Dabekaussen109, Fabrizio D’acapito110, Dimitrios Damaskos111, Giancarlo D’Ambrosio112, Koray Das113, Richard Justin Davies114, Andrew Charles De Beaux115, Sara Patricia De Lebrusant Fernandez 116, Alessandro De Luca117, Francesca De Stefano118, Luca Degrate119, Zaza Demetrashvili120, Andreas Kyriacou Demetriades121, Dzemail Smail Detanac 122, Agnese Dezi123, Giuseppe Di Buono124, Isidoro Di Carlo125, Pierpaolo Di Lascio126, Marcello Di Martino127, Salomone Di Saverio128, Bogdan Diaconescu129, Jose J. Diaz130, Rigers Dibra131, Evgeni Nikolaev Dimitrov132, Vincenza Paola Dinuzzi133, Sandra Dios-Barbeito134, Jehangir Farman Ali Diyani135, Agron Dogjani136, Maurizio Domanin137, Mario D’Oria138, Virginia Duran Munoz-Cruzado139, Barbora East140, Mikael Ekelund141, Gerald Takem Ekwen142, Adel Hamed Elbaih143, Muhammed Elhadi144, Natalie Enninghorst145, Mairam Ernisova146, Juan Pablo Escalera-Antezana147, Sofia Esposito148, Giuseppe Esposito149, Mercedes Estaire150, Camilla Nikita Farè151, Roser Farre 152, Francesco Favi153, Luca Ferrario154, Antonjacopo Ferrario di Tor Vajana155, Claudia Filisetti156, Francesco Fleres157, Vinicius Cordeiro Fonseca158, Alexander Forero-Torres159, Francesco Forfori160, Laura Fortuna161, Evangelos Fradelos162, Gustavo P. Fraga163, Pietro Fransvea164, Simone Frassini165, Giuseppe Frazzetta166, Erica Pizzocaro 167, Maximos Frountzas168, Mahir Gachabayov169, Rita Galeiras170, Alain A. Garcia Vazquez171, Simone Gargarella172, Ibrahim Umar Garzali173, Wagih Mommtaz Ghannam174, Faiz Najmuddin Ghazi175, Lawrence Marshall Gillman176, Rossella Gioco177, Alessio Giordano178, Luca Giordano179, Carlo Giove180, Giorgio Giraudo181, Mario Giuffrida182, Michela Giulii Capponi183, Emanuel Gois Jr.184, Carlos Augusto Gomes185, Felipe Couto Gomes186, Ricardo Alessandro Teixeira Gonsaga187, Emre Gonullu188, Jacques Goosen189, Tatjana Goranovic190, Raquel Gracia-Roman191, Giorgio Maria Paolo Graziano192, Ewen Alexander Griffiths193, Tommaso Guagni194, Dimitar Bozhidarov Hadzhiev195, Muad Gamil Haidar196, Hytham K. S. Hamid197, Timothy Craig Hardcastle198, Firdaus Hayati199, Andrew James Healey200, Andreas Hecker201, Matthias Hecker202, Edgar Fernando Hernandez Garcia203, Adrien Montcho Hodonou204, Eduardo Cancio Huaman205, Martin Huerta206, Aini Fahriza Ibrahim207, Basil Mohamed Salabeldin Ibrahim208, Giuseppe Ietto209, Marco Inama210, Orestis Ioannidis211, Arda Isik212, Nizar Ismail213, Azzain Mahadi Hamid Ismail214, Ruhi Fadzlyana Jailani215, Ji Young Jang216, Christos Kalfountzos217, Sujala Niatarika Rajsain Kalipershad218, Emmanouil Kaouras219, Lewis Jay Kaplan220, Yasin Kara221, Evika Karamagioli222, Aleksandar Karamarkovia223, Ioannis Katsaros224, Alfie J. Kavalakat225, Aristotelis Kechagias226, Jakub Kenig227, Boris Juli Kessel 228, Jim S. Khan229, Vladimir Khokha230, Jae Il Kim231, Andrew Wallace Kirkpatrick232, Roberto Klappenbach233, Yoram Kluger234, Yoshiro Kobe236, Efstratios Kofopoulos Lymperis237, Kenneth Yuh Yen Kok238, Victor Kong239, Dimitris P. Korkolis 240, Georgios Koukoulis241, Bojan Kovacevic242, Vitor Favali Kruger243, Igor A. Kryvoruchko244, Hayato Kurihara245, Akira Kuriyama246, Aitor Landaluce-Olavarria 247, Pierfrancesco Lapolla248, Ari Leppäniemi249, Leo Licari250, Giorgio Lisi251, Andrey Litvin252, Aintzane Lizarazu253, Heura Llaquet Bayo254, Varut Lohsiriwat255, Claudia Cristina Lopes Moreira256, Eftychios Lostoridis257, Agustãn Tovar Luna258, Davide Luppi259, Gustavo Miguel Machain V.260, Marc Maegele261, Daniele Maggiore262, Stefano Magnone263, Ronald V. Maier264, Piotr Major266, Mallikarjuna Manangi267, Andrea Manetti268, Baris Mantoglu269, Chiara Marafante270, Federico Mariani271, Athanasios Marinis272, Evandro Antonio Sbalcheiro Mariot273, Gennaro Martines 275, Aleix Martinez Perez276, Costanza Martino278, Pietro Mascagni279, Damien Massalou280, Maurizio Massaro281, Belen Matías-García282, Gennaro Mazzarella283, Giorgio Mazzarolo284, Renato Bessa Melo285, Fernando Mendoza-Moreno286, Serhat Meric287, Jeremy Meyer288, Luca Miceli289, Nikolaos V. Michalopoulos290, Flavio Milana291, Andrea Mingoli292, Tushar S. Mishra293, Muyed Mohamed294, Musab Isam Eldin Abbas Mohamed295, Ali Yasen Mohamedahmed296, Mohammed Jibreel Suliman Mohammed297, Rajashekar Mohan298, Ernest E. Moore299, Dieter Morales-Garcia300, MÃ¥ns Muhrbeck301, Francesk Mulita 302, Sami Mohamed Siddig Mustafa303, Edoardo Maria Muttillo304, Mukhammad David Naimzada305, Pradeep H. Navsaria306, Ionut Negoi307, Luca Nespoli308, Christine Nguyen309, Melkamu Kibret Nidaw 310, Giuseppe Nigri311, Ioannis Nikolopoulos312, Donal Brendan O’Connor313, Habeeb Damilola Ogundipe314, Cristina Oliveri315, Stefano Olmi316, Ernest Cun Wang Ong317, Luca Orecchia318, Aleksei V. Osipov319, Muhammad Faeid Othman320, Marco Pace321, Mario Pacilli322, Leonardo Pagani323, Giuseppe Palomba324, Desire’ Pantalone325, Arpad Panyko326, Ciro Paolillo327, Mario Virgilio Papa328, Dimitrios Papaconstantinou329, Maria Papadoliopoulou330, Aristeidis Papadopoulos331, Davide Papis332, Nikolaos Pararas333, Jose Gustavo Parreira 334, Neil Geordie Parry335, Francesco Pata336, Tapan Patel 337, Simon Paterson-Brown338, Giovanna Pavone339, Francesca Pecchini340, Veronica Pegoraro341, Gianluca Pellino342, Maria Pelloni343, Andrea Peloso344, Eduardo Perea Del Pozo345, Rita Goncalves Pereira346, Bruno Monteiro Pereira347, Aintzane Lizarazu Perez348, Silvia Pérez349, Teresa Perra350, Gennaro Perrone351, Antonio Pesce352, Lorenzo Petagna353, Giovanni Petracca354, Vorapong Phupong 355, Biagio Picardi356, Arcangelo Picciariello 357, Micaela Piccoli358, Edoardo Picetti360, Emmanouil Pikoulis Pikoulis361, Tadeja Pintar362, Giovanni Pirozzolo363, Francesco Piscioneri364, Mauro Podda365, Alberto Porcu366, Francesca Privitera367, Clelia Punzo368, Silvia Quaresima369, Martha Alexa Quiodettis370, Niels Qvist371, Razrim Rahim372, Filipe Ramalho de Almeida373, Rosnelifaizur Bin Ramely374, Huseyin Kemal Rasa375, Martin Reichert376, Alexander Reinisch-Liese377, Angela Renne378, Camilla Riccetti379, Maria Rita Rodriguez-Luna380, Daniel Roizblatt381, Andrea Romanzi382, Luigi Romeo383, Francesco Pietro Maria Roscio384, Ramely Bin Rosnelifaizur 385, Stefano Rossi386, Andres M Rubiano387, Elena Ruiz-Ucar388, Boris Evgeniev Sakakushev389, Juan Carlos Salamea 390, Ibrahima Sall391, Lasitha Bhagya Samarakoon392, Fabrizio Sammartano393, Alejandro Sanchez Arteaga394, Sergi Sanchez-Cordero395, Domenico Pietro Maria Santoanastaso396, Massimo Sartelli397, Diego Sasia398, Norio Sato399, Artem Savchuk400, Robert Grant Sawyer401, Giacomo Scaioli402, Dimitrios Schizas403, Simone Sebastiani404, Barbara Seeliger405, Helmut Alfredo Segovia Lohse406, Charalampos Seretis407, Giacomo Sermonesi408, Mario Serradilla-Martin409, Vishal G. Shelat410, Sergei Shlyapnikov411, Theodoros Sidiropoulos 412, Romeo Lages Simoes413, Leandro Siragusa414, Boonying Siribumrungwong415, Mihail Slavchev416, Leonardo Solaini417, gabriele soldini418, Andrey Sopuev419, Kjetil Soreide420, Apostolos Sovatzidis421, Philip Frank Stahel422, Matt Strickland423, Mohamed Arif Hameed Sultan424, Ruslan Sydorchuk425, Larysa Sydorchuk426, Syed Muhammad Ali Muhammad Syed427, Luis Tallon-Aguilar428, Andrea Marco Tamburini429, Nicolò Tamini430, Edward C .T. H. Tan431, Jih Huei Tan432, Antonio Tarasconi433, Nicola Tartaglia434, Giuseppe Tartaglia435, Dario Tartaglia436, John Vincent Taylor437, Giovanni Domenico Tebala438, Ricardo Alessandro Teixeira Gonsaga439, Michel Teuben440, Alexis Theodorou441, Matti Tolonen442, Giovanni Tomasicchio443, Adriana Toro444, Beatrice Torre445, Tania Triantafyllou446, Giuseppe Trigiante Trigiante 447, Marzia Tripepi 448, Julio Trostchansky449, Konstantinos Tsekouras450, Victor Turrado-Rodriguez451, Roberta Tutino452, Matteo Uccelli453, Petar Angelov Uchikov454, Bakarne Ugarte-Sierra455, Mika Tapani Ukkonen456, Michail Vailas457, Panteleimon G. Vassiliu458, Alain Garcia Vazquez459, Rita Galeiras Vazquez460, George Velmahos461, Juan Ezequiel Verde462, Juan Manuel Verde463, Massimiliano Veroux464, Jacopo Viganò465, RAMON VILALLONGA466, Diego Visconti467, Alessandro Vittori468, Maciej Waledziak469, Tongporn Wannatoop470, Lukas Werner Widmer471, Michael Samuel James Wilson472, Sarah Woltz473, Ting Hway Wong474, Sofia Xenaki475, Byungchul Yu476, Steven Yule477, Sanoop Koshy Zachariah478, Georgios Zacharis479, Claudia Zaghi480, Andee Dzulkarnaen Zakaria481, Diego A. Zambrano482, Nikolaos Zampitis483, Biagio Zampogna484, Simone Zanghì485, Maristella Zantedeschi486, Konstantinos Zapsalis487, Fabio Zattoni488, Monica Zese489.