Abstract

Background

The Promoting Action on Research Implementation in Health Services (PARIHS) framework was developed two decades ago and conceptualizes successful implementation (SI) as a function (f) of the evidence (E) nature and type, context (C) quality, and the facilitation (F), [SI = f (E,C,F)]. Despite a growing number of citations of theoretical frameworks including PARIHS, details of how theoretical frameworks are used remains largely unknown. This review aimed to enhance the understanding of the breadth and depth of the use of the PARIHS framework.

Methods

This citation analysis commenced from four core articles representing the key stages of the framework’s development. The citation search was performed in Web of Science and Scopus. After exclusion, we undertook an initial assessment aimed to identify articles using PARIHS and not only referencing any of the core articles. To assess this, all articles were read in full. Further data extraction included capturing information about where (country/countries and setting/s) PARIHS had been used, as well as categorizing how the framework was applied. Also, strengths and weaknesses, as well as efforts to validate the framework, were explored in detail.

Results

The citation search yielded 1613 articles. After applying exclusion criteria, 1475 articles were read in full, and the initial assessment yielded a total of 367 articles reported to have used the PARIHS framework. These articles were included for data extraction. The framework had been used in a variety of settings and in both high-, middle-, and low-income countries. With regard to types of use, 32% used PARIHS in planning and delivering an intervention, 50% in data analysis, 55% in the evaluation of study findings, and/or 37% in any other way. Further analysis showed that its actual application was frequently partial and generally not well elaborated.

Conclusions

In line with previous citation analysis of the use of theoretical frameworks in implementation science, we also found a rather superficial description of the use of PARIHS. Thus, we propose the development and adoption of reporting guidelines on how framework(s) are used in implementation studies, with the expectation that this will enhance the maturity of implementation science.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

There has been an increased use of theoretical frameworks in the field of implementation science in the last decade, with most developed in the last two decades [1, 2]. Tabak et al. identified 61 theoretical models used in dissemination and implementation science [3]. However, while theoretical frameworks are increasingly being cited, more research is needed to understand how they are chosen and applied, and how their use relates to improved implementation outcomes [1, 4]. Variously described in the form of theories, frameworks, or models, all strive to provide conceptual clarity on different aspects of implementation practice and research. For consistency, we will refer to these as theoretical frameworks, or simply “frameworks.”

The Promoting Action on Research Implementation in Health Services (PARIHS) framework is a multi-dimensional framework which was developed to explicitly challenge the pipeline conceptualization of implementation [5]. The PARIHS framework is a commonly used conceptual framework [1, 4] that posits successful implementation (SI) as a function (f) of the nature and type of evidence (E) (including research, clinical experience, patient experience, and local information), the qualities of the context (C) of implementation (including culture, leadership, and evaluation), and the way the implementation process is facilitated (F) (internal and/or external person acting as a facilitator to enable the process of implementation); SI = f(E,C,F). The framework was informed by Rogers’ Diffusion of Innovations [6] and various organizational theories and theories from social science [7] and generated inductively by working with clinical staff to help them understand the practical nature of getting evidence into practice. The PARIHS framework was initially published in 1998 [5] and updated based on a conceptual analysis in 2002 [8] and further primary research [9]. A further refinement was undertaken in 2015 [10], resulting in the integrated or i-PARIHS. Articles using the revised version are not included in the citation analysis reported here. The PARIHS framework has been described as a determinant framework in that it specifies determinants that act as barriers and enablers influencing implementation outcomes [2]. Skolarus et al. [1] identified Kitson et al. [5] as one of the two primary originating sources of influence in their citation analysis of dissemination and implementation frameworks.

Despite the growing number of citations of theoretical frameworks in scientific articles, the detail of how frameworks are used remains largely unknown. Systematic reviews of the application of two other commonly used frameworks [1], the Knowledge to Action framework [11] and the Consolidated Framework for Implementation Research [12], both reported that use of these frameworks, beyond simply citation, was uncommon. While PARIHS has been widely cited, it has also been scrutinized; in 2010, Helfrich et al. published a qualitative critical synthesis of studies that had used the PARIHS framework [13], finding six core concept articles and 18 empirical articles. One of the reported findings was that PARIHS was generally used as an organizing framework for analysis. At the time, no studies used PARIHS prospectively to design implementation strategies [13]. A systematic review applying citation analysis to map the use of PARIHS (similar to those undertaken for the Knowledge to Action framework (KTA) [11] and the Consolidated Framework for Implementation Research (CFIR) [12]) has not yet been performed.

Systematic reviews can contribute to the development of existing theoretical frameworks by critically reviewing what authors state as their weaknesses and strengths; they can also direct future and current users of frameworks to examples of using the frameworks in different ways. To contribute to this development from the perspective of the PARIHS framework, we undertook a citation analysis of the published peer-reviewed literature that focused on the reported use of PARIHS (and its main elements), in what contexts the framework has been applied, and what scholars who have used the PARIHS framework (and its main elements) report as its strengths, limitations, and validity.

Methods

The method used for this study is citation analysis, i.e., the examination of the frequency and patterns of citations in scientific articles, in this case articles citing the core PARIHS framework publications. A team of researchers with engagement in the development and/or use of the PARIHS framework was constituted. Initially, the group decided on the core publications for the citation analysis. Four articles were selected as they represented the key stages of the framework’s development, namely the original paper that described PARIHS, plus three subsequent papers that informed and outlined revisions to the framework:

-

1.

Kitson A, Harvey G, McCormack B. Enabling the implementation of evidence-based practice: a conceptual framework. Qual Health Care. 1998;7(3):149-58.

-

2.

Rycroft-Malone J, Kitson A, Harvey G, McCormack B, Seers K, Titchen A, et al. Ingredients for change: revisiting a conceptual framework. BMJ Quality Saf. 2002;11(2):174-80.

-

3.

Rycroft-Malone J, Harvey G, Seers K, Kitson A, McCormack B, Titchen A. An exploration of the factors that influence the implementation of evidence into practice. J Clin Nurs. 2004;13(8):913-24.

-

4.

Kitson AL, Rycroft-Malone J, Harvey G, McCormack B, Seers K, Titchen A. Evaluating the successful implementation of evidence into practice using the PARiHS framework: theoretical and practical challenges. Implement Sci. 2008;3:1.

Citation search

Citation searches were performed by an information specialist (KG) to retrieve published articles citing any of the four core articles. The searches were performed in two citation databases: Web of Science and Scopus. The first searches were performed between 31 March 2016 and 1 April 2016. Later, 6 September 2019, additional searches were performed in respective databases. These searches were limited to citations that were published 1 April 2016–31 August 2019 to update the result from the first searches. All citations that were published September 1998 (i.e., when Kitson et al 1998 was published)–31 August 2019 (i.e., prior to the search date) in respective databases were collected in EndNote Library. Endnote was used for checking duplicates and retrieving full texts. To manage the scope of the citation analysis, we opted to only include articles in English published in peer-reviewed scientific journals. The searches in Web of Science were, because of the subscription, limited to Web of Science Core Collection without Book Citation Index.

Data extraction

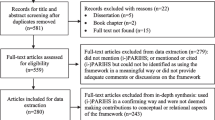

The Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA) flow diagram [14] for the data extraction is provided in Fig. 1. Initially, an assessment to identify the articles that used the PARIHS framework in any other way than merely referencing one or more of the core articles was performed (Additional file 1). For this initial assessment, all articles were read in full. After identifying articles where the PARIHS framework was used, data extraction was undertaken using a tailor-made data capture form (Additional file 1). The data capture form was developed and piloted in iterative cycles by the research team. Apart from capturing information about where (country/countries and setting/s) and with whom (professional groups and roles) PARIHS had been applied, the form included questions on whether PARIHS was used in one or more of the following ways:

-

1)

In planning and delivering an intervention,

-

2)

In data analysis,

-

3)

In the evaluation of study findings, and/or

-

4)

In any other way.

Each of these questions was followed by an open-ended item for extracting information on how this was reported [15]. To enhance reliability and data richness, each reviewer copy-pasted sections of the article corresponding to the open-ended reply into the data extraction form when appropriate and indicated page, column, and row. Two additional items captured whether the PARIHS framework had been tested or validated, as well as any reported strengths and weaknesses of the framework. Thus, we report on what the authors of the included articles claim to have done, rather than a judgment as to how and to what extent they actually used the PARIHS framework.

For data extraction and validation, the research team was divided into four pairs, ensuring that each article was assessed separately by at least two research team members. The pairs received batches of 20 articles at a time. Variations in the assessments were discussed until consensus was reached within the pair(s). Further, queries detected within the pairs were raised and discussed with the whole research team, until consensus was achieved. Regular whole-team online meetings were held to consolidate findings between every new batch of articles and throughout the development and analysis process. In total, the group had > 20 online meetings and four face-to-face meetings from the initial establishment of the group in January 2015.

Data analysis

Categorical data were analyzed using descriptive statistics, whereas the open-ended items were analyzed qualitatively [16], including the collated extractions of data to illustrate each of the four types of use (i.e., how the PARIHS framework was depicted in terms of (1) planning and delivering an intervention, (2) analysis, (3) evaluation of study findings, and/or (4) in any other way).

Applying a content analysis approach [17], members of the research team worked separately with the texts extracted from the reviewed articles. The extracts for each open-ended item were read and reread, to get a sense of the whole. Next, variations were identified and formed as categories. Findings for each question were summarized in short textual descriptions, which were shared with the whole team. In a face-to-face meeting, the data relating to each question were critically discussed and comparisons were made between the findings for each question, to identify overlaps and relationships about how PARIHS has been used.

Results

After duplicate control, 1613 references remained. These were sorted by language and type of publication. In this phase, 131 references categorized as books, book chapters, conference proceedings, and publications written in non-English language were excluded. Also, three of the four core articles (i.e., the three citing Kitson et al. [5] which was the starting point for development of the PARIHS framework and therefore did not appear in the citation search) were excluded from the database [8, 9, 18], as were four articles expanding and refining PARIHS [19,20,21,22]. Accordingly, 1475 articles remained, and after the assessment excluding those merely citing PARIHS, a further 1108 articles were excluded, leaving 367 articles that cited one or more of the core articles, and made explicit use of the PARIHS framework (see Fig. 1 and Table 1).

Of these 367 articles, 235 cited Kitson et al. [5], 208 cited Kitson et al. [18], 136 cited Rycroft-Malone et al. [8], and 92 cited Rycroft-Malone et al. [9]. In total, the 367 articles consisted of 35 protocols [25, 28, 29, 31,32,33,34,35,36,37,38, 40, 42, 44,45,46,47,48,49,50, 52,53,54, 56, 57]. A further 255 articles reported empirical studies:

▪ 91 where PARIHS guided the development of the intervention [58,59,60,61,62,63,64,65,66,67,68,69,70,71,72,73,74,75,76,77,78,79,80,81,82, 84,85,86,87,88,89,90,91,92,93,94,95,96,97,98,99,100,101,102,103,104,105,106,107,108,109,110,111,112,113,114,115,116,117,118,119,120,121,122,123,124,125,126,127,128,129,130,131,132,133,134,135,136,137,138,139,140,141,142,143, 145, 146, 386,387,388],

▪ 92 intervention studies where PARIHS did not guide the development of an intervention [149, 152, 153, 155, 156, 158, 160, 162, 167, 168, 171, 176, 178, 179, 182,183,184,185, 194, 201,202,203, 205,206,207,208,209, 211, 212, 214, 217, 219,220,221,222,223, 225, 234,235,236, 243,244,245, 249,250,251,252, 254, 255, 258,259,260,261, 263, 265, 266, 268,269,270, 273, 274, 276,277,278,279,280,281,282,283,284,285, 287,288,289,290,291,292, 296, 297, 299,300,301, 303,304,305,306,307,308,309,310,311,312],

▪ 72 non-intervention studies [150, 151, 154, 157, 159, 161, 163,164,165,166, 169, 170, 172,173,174,175, 177, 180, 181, 186,187,188,189,190,191,192,193, 195,196,197,198,199,200, 204, 210, 213, 215, 216, 218, 224, 226,227,228,229,230,231,232,233, 237,238,239,240,241,242, 246,247,248, 253, 256, 257, 262, 264, 267, 271, 272, 275, 286, 293,294,295, 298, 302]

In addition, the database included 28 empirical review studies [3, 13, 313, 314, 316,317,318,319,320,321,322,323,324,325,326,327,328,329,330,331,332,333,334,335,336,337,338, 389] and 49 opinion/theoretical articles [2, 144, 339,340,341,342,343,344,345,346,347,348,349,350,351,352,353,354,355,356,357,358,359,360,361,362,363,364,365,366,367,368,369,370,371,372,373,374,375,376,377,378,379,380,381,382,383,384,385]. In terms of professional focus, about 65% of the included articles involved nursing.

In the following sections, references have been added to the categorical items in the data extraction while we have opted only to provide examples of references to the findings from the qualitative exploration of how the PARIHS framework was operationalized in detail.

Settings

Of the articles reporting type of setting where the implementation project/research took place, a majority were undertaken in hospitals (n = 126) [26, 27, 30, 38, 39, 41, 42, 45, 49, 51,52,53,54,55, 60, 62,63,64, 67, 70,71,72, 77, 84, 85, 88, 89, 95,96,97,98, 103, 106, 107, 111, 115,116,117,118, 120,121,122, 128, 131, 132, 136, 137, 139, 143, 146, 149, 151, 153,154,155, 157, 161, 165, 167,168,169, 172, 173, 175, 180,181,182, 184, 186, 190,191,192,193, 205, 207, 212, 215, 221, 223, 227, 230, 231, 240, 243, 244, 246, 248,249,250,251, 256, 258, 260, 265, 268, 271, 273,274,275, 277,278,279, 281, 282, 284, 288,289,290, 294, 296, 298, 299, 301, 305, 306, 312, 314, 320, 336, 352, 353, 360, 362, 382, 386, 388], followed by a combination of multiple healthcare settings (n = 80) [31, 35, 37, 47, 50, 56, 65, 66, 68, 73, 79, 92, 99, 100, 109, 110, 112, 114, 133, 138, 144, 145, 150, 159, 160, 162, 163, 171, 177, 183, 187, 194, 197, 204, 208,209,210, 216, 218, 219, 226, 228, 233, 238, 245, 253, 262, 264, 276, 280, 283, 287, 292, 293, 295, 302, 307,308,309,310, 313, 321, 323, 326, 327, 329, 330, 333, 337, 338, 344, 345, 365, 367, 368, 371, 373, 376, 387, 389], community/social care settings (n = 54) [24, 34, 36, 43, 44, 46, 48, 57, 59, 61, 69, 74,75,76, 80, 81, 86, 87, 94, 102, 104, 108, 113, 123, 129, 134, 142, 152, 156, 158, 174, 178, 185, 195, 201, 203, 214, 217, 222, 229, 232, 241, 257, 263, 266, 269, 270, 300, 304, 351, 355, 357, 363], primary health care (n = 34) [23, 25, 28, 29, 40, 58, 82, 90, 93, 119, 125, 130, 140, 141, 164, 170, 196, 198, 200, 202, 224, 225, 235, 236, 242, 252, 259, 261, 272, 285, 286, 291, 332, 340], and home-based care (n = 7) [78, 91, 105, 166, 254, 255, 311]. Five articles were derived from special settings such as construction [176], education [101], pharmacies [135], urban planning [383], and public health institutions [32]. In 44 articles [2, 3, 13, 33, 124, 126, 127, 179, 206, 211, 220, 237, 239, 247, 297, 316, 317, 322, 324, 325, 328, 339, 341,342,343, 346,347,348,349,350, 354, 356, 358, 364, 369, 372, 374, 375, 377, 378, 380, 381, 384, 385], the setting was not reported or not applicable (e.g., opinion/theoretical articles). For empirical studies and published protocols, about 28% were derived from research in the USA, 22% from Canada, 10% from Sweden, and 10% from the UK. The remaining articles mainly originated from other high-income countries in Europe; in addition, there were a few articles reporting studies in low- and middle-income countries, including Vietnam, Tanzania, Mozambique, and Uganda [46, 82, 110, 150, 235, 287].

Timing of different types of articles

The types of articles published using the PARIHS framework changed over time, with an increase in the number of empirical studies from 2004 onwards, as illustrated in Fig. 2. As the search for articles for this review only included the first eight months of 2019, the graph is limited to full years (i.e., 1998 through 2018).

Use of PARIHS

Figure 3 depicts how PARIHS was used by type of article. Although authors frequently claimed that PARIHS was used in one or more ways, details as to how the framework was used were often lacking.

The application of PARIHS to plan and deliver an intervention

In total, 117 (32%) articles claimed to use the PARIHS framework to plan and deliver an intervention [23,24,25,26,27,28,29,30,31,32,33,34,35,36,37,38,39,40,41,42,43,44,45,46, 58,59,60,61,62,63,64,65,66,67,68,69,70,71,72,73,74,75,76,77,78,79,80,81,82, 84,85,86,87,88,89,90,91,92,93,94,95,96,97,98,99,100,101,102,103,104,105,106,107,108,109,110,111,112,113,114,115,116,117,118,119,120,121,122,123,124,125,126,127,128,129,130,131,132,133,134,135,136,137,138,139,140,141,142,143, 145, 146, 339, 340, 386,387,388]. Predominantly, these were empirical studies (n = 91) [58,59,60,61,62,63,64,65,66,67,68,69,70,71,72,73,74,75,76,77,78,79,80,81,82, 84,85,86,87,88,89,90,91,92,93,94,95,96,97,98,99,100,101,102,103,104,105,106,107,108,109,110,111,112,113,114,115,116,117,118,119,120,121,122,123,124,125,126,127,128,129,130,131,132,133,134,135,136,137,138,139,140,141,142,143, 145, 146, 386,387,388] but also two opinion/theoretical articles [339, 340] and 24 protocols [23,24,25,26,27,28,29,30,31,32,33,34,35,36,37,38,39,40,41,42,43,44,45,46]. Of the 117 articles, about half stated that the framework was used for theoretically informing, framing, or guiding an intervention (e.g., [82, 103, 105, 134, 386]). However, in these studies, PARIHS was referred to only in a general sense, in that the core elements of the framework were said to have informed the planning of the study. There was a lack of detail provided about what elements of the framework were used and how they were operationalized to plan and deliver an intervention. In the other half of the 117 articles, it was described more specifically that one or more elements of the framework had been used. Most commonly the facilitation element (e.g., [58, 80, 92, 98, 110]) was referred to as guiding an implementation strategy. The articles that provided explicit descriptions of interventions using facilitation employed strategies such as education, reminders, audit-and-feedback, action learning, and evidence-based quality improvement, and roles including internal and external facilitators and improvement teams to enable the uptake of evidence (e.g., [23, 79, 125, 142]). Some articles drew on the PARIHS framework more specifically, to understand the role of organizational context in implementation (e.g., [34, 63, 145, 340]).

The application of PARIHS in data analysis

There were 184 (50%) articles where the PARIHS framework was reported to be used in the analysis [2, 13, 23,24,25,26,27,28,29,30,31,32,33,34,35, 47,48,49,50,51,52,53,54,55, 58,59,60,61,62,63,64,65,66,67,68,69,70,71,72,73,74,75,76,77,78,79,80,81,82, 84,85,86,87,88,89,90,91,92,93,94, 149,150,151,152,153,154,155,156,157,158,159,160,161,162,163,164,165,166,167,168,169,170,171,172,173,174,175,176,177,178,179,180,181,182,183,184,185,186,187,188,189,190,191,192,193,194,195,196,197,198,199,200,201,202,203,204,205,206,207,208,209,210,211,212,213,214,215,216,217,218,219,220,221,222,223,224,225,226,227,228,229,230,231,232,233,234,235,236,237,238,239,240,241,242, 313, 314, 316,317,318,319,320,321,322, 339, 341,342,343,344,345,346,347,348,349,350,351,352,353,354,355,356,357,358, 386, 389]. Most of these involved empirical studies (n = 131) [58,59,60,61,62,63,64,65,66,67,68,69,70,71,72,73,74,75,76,77,78,79,80,81,82, 84,85,86,87,88,89,90,91,92,93,94, 149,150,151,152,153,154,155,156,157,158,159,160,161,162,163,164,165,166,167,168,169,170,171,172,173,174,175,176,177,178,179,180,181,182,183,184,185,186,187,188,189,190,191,192,193,194,195,196,197,198,199,200,201,202,203,204,205,206,207,208,209,210,211,212,213,214,215,216,217,218,219,220,221,222,223,224,225,226,227,228,229,230,231,232,233,234,235,236,237,238,239,240,241,242, 386] where PARIHS often was described as guiding or framing the data collection, e.g., developing an interview guide, and/or analysis, but with no further details. In articles that provided more detailed information, PARIHS was used to guide or frame qualitative analyses in about 50 studies (e.g., [67, 94, 173, 178, 207]). Of these, around 20 used a deductive approach in that they used the elements and sub-elements to structure the analytic process (e.g., [150, 170, 188, 215, 242]). About 35 studies applied PARIHS for quantitative analysis, (e.g., [69, 168, 174, 190, 211]). In half of these, the Alberta Context Tool (e.g., [155, 165, 180, 195, 229]) and the Organizational Readiness to Change Assessment Tool (e.g., [74, 159, 219, 240]) were used; both these tools being derived from PARIHS. Empirical studies using the PARIHS framework in the analysis encompassed primarily all three main elements of PARIHS (e.g., [166, 181, 193, 221]) and the context domain (e.g., [78, 152, 153, 207]), and in lesser extent the evidence (e.g., [185, 208, 214]) and the facilitation domain (e.g., [58, 67, 79, 182]).

Eleven review studies [13, 313, 314, 316,317,318,319,320,321,322, 389] used the framework for the analysis; findings were mapped to PARIHS elements in a few studies [316, 317, 389]; one described that their data had been “analysed through the lens of PARIHS” (p1) [389]. A couple of the review studies had PARIHS as the object for analysis, comparing it with other frameworks [318, 322]. This approach was also common in the 20 opinion/theoretical articles [2, 339, 341,342,343,344,345,346,347,348, 350,351,352,353,354,355,356,357,358], where the PARIHS framework itself was the focus of the analysis (e.g., [341, 349, 354]). In these articles, the analysis was performed in different ways, primarily through mapping and comparing PARIHS to other frameworks or models or even policies, but also for general discussions on implementation and evidence-based practice. Among the 185 articles that reported using the PARIHS framework in the analysis, there were also 22 protocols where authors reported that the intention was to use the framework in the analysis [23,24,25,26,27,28,29,30,31,32,33,34,35, 47,48,49,50,51,52,53,54,55].

The application of PARIHS in the evaluation of study findings

A total of 203 (55%) included articles provided information on how the PARIHS framework was used in the evaluation of study findings, in terms of contributing to the discussion and interpretation of results [13, 52, 58,59,60,61,62,63,64,65,66,67,68,69,70,71,72,73,74,75,76,77,78,79,80,81,82, 84,85,86,87,88,89, 95,96,97,98,99,100,101,102,103,104,105,106,107,108,109,110,111,112,113,114,115,116,117,118,119,120,121, 149,150,151,152,153,154,155,156,157,158,159,160,161,162,163,164,165,166,167,168,169,170,171,172,173,174,175,176,177,178,179,180,181,182,183,184,185,186,187,188,189,190,191,192,193,194,195,196,197,198,199,200,201,202,203,204,205,206,207,208,209,210,211,212,213,214, 243,244,245,246,247,248,249,250,251,252,253,254,255,256,257,258,259, 261,262,263,264,265,266,267,268,269,270,271,272,273,274,275,276,277,278,279,280,281,282,283,284, 313, 314, 316,317,318,319,320, 323,324,325,326,327,328,329,330,331, 339, 341,342,343,344,345,346,347,348,349,350, 359,360,361,362,363,364,365, 386, 389]. The majority (n = 167) of these were empirical studies [52, 58,59,60,61,62,63,64,65,66,67,68,69,70,71,72,73,74,75,76,77,78,79,80,81,82, 84,85,86,87,88,89, 95,96,97,98,99,100,101,102,103,104,105,106,107,108,109,110,111,112,113,114,115,116,117,118,119,120,121, 149,150,151,152,153,154,155,156,157,158,159,160,161,162,163,164,165,166,167,168,169,170,171,172,173,174,175,176,177,178,179,180,181,182,183,184,185,186,187,188,189,190,191,192,193,194,195,196,197,198,199,200,201,202,203,204,205,206,207,208,209,210,211,212,213,214, 243,244,245,246,247,248,249,250,251,252,253,254,255,256,257,258,259, 261,262,263,264,265,266,267,268,269,270,271,272,273,274,275,276,277,278,279,280,281,282,283,284, 386].

We found two main approaches to how the PARIHS framework was used in the evaluation of study findings. First, PARIHS was used to organize the discussion of the findings (e.g., [73, 87, 109, 166, 214]), where the framework and/or its elements were used to provide a structure for reporting or generally discussing the findings, or both, for example in stating that the key elements of PARIHS were reflected in the study findings. Second, the framework was used to consider the implications of the study’s findings (e.g., [81, 84, 170, 207, 361]), where the framework or its elements (varying between one (e.g., [75, 195, 211]), two (e.g., [71, 86, 105]), and all the three main elements (e.g., [80, 261, 269])) enabled authors to elaborate on findings, or reflect on the implications of their study to evaluate the PARIHS framework itself. Specifically, we found some empirical articles reported evaluating the PARIHS element “context” by means of context tools (e.g., [155]). In addition, an evaluation of the study findings using the framework was identified in 18 opinion/theoretical articles [339, 341,342,343,344,345,346,347,348,349,350, 359,360,361,362,363,364,365] and 18 empirical review studies [13, 313, 314, 316,317,318,319,320, 323,324,325,326,327,328,329,330,331, 389]. Among the opinion/theoretical articles, there were papers evaluating other theoretical constructions in relation to the PARIHS framework (e.g., [364]).

The application of PARIHS in any other way

A total of 136 (37%) reported using PARIHS in some other way than directly informing the planning and delivery of an intervention or analyzing and evaluating findings [3, 23,24,25, 36, 37, 47,48,49,50, 56,57,58,59,60,61,62, 90, 95,96,97, 122,123,124,125,126,127, 144, 149,150,151,152,153,154,155,156,157,158,159,160,161,162,163,164,165,166,167,168,169,170, 215,216,217,218,219,220,221,222,223,224, 243,244,245,246,247,248,249,250,251,252,253,254,255,256, 285,286,287,288,289,290,291,292,293,294,295,296,297,298,299,300,301,302,303,304,305,306,307,308,309,310,311,312,313, 323, 324, 332,333,334,335,336,337,338, 351, 359,360,361, 366,367,368,369,370,371,372,373,374,375,376,377,378,379,380,381,382,383,384,385]. A majority of these articles (n = 89) were empirical studies [58,59,60,61,62, 90, 95,96,97, 122,123,124,125,126,127, 149,150,151,152,153,154,155,156,157,158,159,160,161,162,163,164,165,166,167,168,169,170, 215,216,217,218,219,220,221,222,223,224, 243,244,245,246,247,248,249,250,251,252,253,254,255,256, 285,286,287,288,289,290,291,292,293,294,295,296,297,298,299,300,301,302,303,304,305,306,307,308,309,310,311,312], and about half of these described the use of PARIHS as an overall guide to frame the study (e.g., [58, 60, 168, 222, 285, 303]). A similar finding was apparent in the 11 protocols [23,24,25, 36, 37, 47,48,49,50, 56, 57]; about half of these also referred to the use of PARIHS to guide and frame the study design (e.g., [47, 48, 50, 57]).

An alternative use of PARIHS in empirical studies involved focusing on one of the three PARIHS elements (n = 17) and investigating them in greater depth, most notably context (n = 10) (e.g., [155, 232]) and facilitation (n = 7) (e.g., [307, 312]). A total of 25 opinion/theoretical articles [144, 351, 359,360,361, 366,367,368,369,370,371,372,373,374,375,376,377,378,379,380,381,382,383,384,385] reported using the PARIHS framework in some other way, including a discussion about PARIHS as part of presenting a general overview of theories and frameworks to inform implementation (e.g., [369, 376, 378, 384]), using PARIHS to augment, develop, or evaluate other implementation models and frameworks (e.g., [318, 359, 367, 374, 382]), and informing education and learning and teaching initiatives [144, 372]. Empirical review articles (n = 11) included reviews of implementation frameworks [3, 313, 323, 324, 332,333,334,335,336,337,338], including PARIHS, a review of the facilitation dimension of PARIHS and a discussion of the potential to combine implementation and improvement methodologies.

Testing and providing views on the validity of the framework

A total of 102 (28%) articles described testing or validating PARIHS, or provided comments on the validity of the framework [3, 13, 23, 24, 35, 44, 46, 58, 60, 62, 64, 67, 71, 74, 76, 78,79,80,81, 84, 85, 89, 98, 105, 107, 110, 113, 115, 120, 121, 143, 149, 150, 153, 155, 157,158,159, 166, 168, 170, 172, 180,181,182, 187, 188, 190, 191, 195, 198, 201, 203, 204, 206,207,208,209, 211, 212, 214, 229, 246, 249, 250, 252, 253, 255, 264, 267, 268, 277, 278, 280, 281, 287, 303, 308, 314, 316,317,318,319, 322, 323, 326, 330, 332, 333, 335, 336, 341, 342, 345,346,347, 349, 359, 364, 369, 381, 386]. Of these, 72 were empirical studies [4, 58, 60, 62, 64, 67, 71, 74, 76, 78,79,80,81, 84, 85, 89, 98, 105, 107, 110, 113, 115, 120, 121, 143, 149, 150, 153, 155, 157,158,159, 166, 168, 170, 172, 180,181,182, 187, 188, 190, 191, 195, 198, 201, 203, 204, 206,207,208,209, 211, 212, 214, 229, 246, 249, 250, 252, 253, 255, 264, 267, 268, 277, 278, 280, 281, 287, 303, 308, 386], five were study protocols [23, 24, 35, 44, 46], 10 opinion/theoretical articles [341, 342, 345,346,347, 349, 359, 364, 369, 381], and 15 empirical reviews [3, 13, 314, 316,317,318,319, 322, 323, 326, 330, 332, 333, 335, 336]. Empirical studies either tested the whole or parts of the framework with a focus on:

▪ The validity of the whole framework (e.g., [24, 74, 157, 195, 209])

▪ The validity of context (e.g., [155, 190, 280, 287, 308])

▪ The validity of facilitation (e.g., [23, 58, 182, 206])

▪ The validity of evidence (e.g., [255])

▪ Identifying gaps in the framework (e.g., [64, 170, 326])

Over the review study period (1998 to 2019), among empirical studies, there was a shift from primarily studying the context element of the framework to more articles evaluating the whole framework. This was also evident in the pattern found in the protocols, which mostly focused on testing facilitation (e.g., [58, 182, 206]). Opinion/theoretical articles tended to critique the whole framework (e.g., [319, 326, 342, 349, 369]). Of the 15 empirical reviews, the majority focused on the whole framework (e.g., [13, 322, 333]), then on context (e.g., [316, 318, 335]) and then on facilitation (e.g., [323]). Of note is the lack of attention in the literature to the element of “evidence” in the PARIHS framework (examples of articles paying attention to evidence include [208, 255]).

The articles varied in detail, depth, and quality in terms of descriptions of how they went about testing the validity of the PARIHS framework. Approaches ranged from general observations of whether the research teams/users found the elements and sub-elements easy to use (e.g., [62, 188, 203]), to studies that used elements of context described in the PARIHS framework to validate new context measures across settings and groups (e.g., [150, 155, 207]). As one example, the Alberta Context Tool started from the PARIHS conceptualization of context to include dimensions of culture, leadership, and evaluation.

Regarding the strength and limitations of the PARIHS framework, about one third of the included articles reported on its strengths and about 10% commented on perceived limitations. The identified strengths included:

▪ Holistic implementation framework (e.g., [141, 164, 209, 258]) that is perceived as intuitive and accessible.

▪ Both practical and theoretical and therefore feasible to use by both clinicians and researchers; also seen as intuitive to use and accessible (e.g., [117, 209, 255]).

▪ Can be used as a tool: diagnostic/process/evaluative tool; predictive/explanatory tool or as a way to explain the interplay of factors (e.g., [93, 205, 255, 285, 379]).

▪ Can accommodate a range of other theoretical perspectives (including approaches such as social network theory, participatory action research, coaching, change management and other knowledge translation frameworks) (e.g., [93, 105, 245, 246]).

▪ Can be used successfully in a range of different contexts (low- and middle-income countries) [150] and services and for various groups of patients (disability, aged care) (e.g., [80, 113, 248, 312]).

Limitations of the PARIHS framework included:

▪ Poor operationalization of key terms leading to difficulties in understanding and an overlap of elements and sub-elements (e.g., [165, 285, 376]).

▪ Lack of practical guidance on steps to operationalize the framework (e.g., [209, 254]) with a subsequent lack of tools.

▪ Lack of information on the individual and their characteristics (e.g., [209, 361]) and their lack of understanding of evidence (e.g., [204, 390]).

▪ Too structured and does not acknowledge the multidimensionality and uncertainty of implementation (e.g., [143, 214]).

▪ Lack of acknowledgement of wider contextual issues such as the impact of professional, socio-political, and policy issues on implementation (e.g., [115, 143, 285, 354]).

▪ Not providing support in how to overcome barriers to successful implementation (e.g., [88]).

Discussion

In a recent survey among implementation scientists, the PARIHS framework was found to be one of the sixth most commonly used theoretical frameworks [4]. Yet, in our review, about 23% (n = 367) of the identified 1614 articles citing any of the four selected core PARIHS articles used the framework in any substantial way. Similarly, a review of the CFIR found that 26/429 (6%) of articles citing the framework were judged to use the framework in a meaningful way (i.e., used the CFIR to guide data collection, measurement, coding, analysis, and/or reporting) [12]. A citation analysis of the KTA framework found that about 14% (146/1057) of screened abstracts described using the KTA to varying degrees, although only 10 articles were judged to have applied the framework in a fully integrated way to inform the design, delivery, and evaluation of implementation activities [11].

PARIHS has been used in a diverse range of settings but, similarly to other commonly used implementation frameworks, most often superficially or partially. The whole framework has seldom been used holistically to guide all aspects of implementation studies. Implementation science scholars have repeatedly argued that the underuse, superficial use, and misuse of implementation frameworks might reduce the potential scientific advancements in the field, but also the capacity for changing healthcare practice and outcomes [4]. The rationale for not using the whole PARIHS framework could be many, including the justified reason of only being interested in a particular element. As such, partial use cannot always be considered as inappropriate. Simultaneously, many researchers entering the field might be overwhelmed with the many frameworks available and the lack of guidance about how to select and operationalize them and using their elements [2, 4, 391]. The current citation analysis can thus help remedy a gap in the literature by revealing how the PARIHS framework has been used to date, in full or partially, and thus provides input to users of its potential use.

The use of theoretical frameworks in implementation science serves the purpose of guiding researchers’ and practitioners’ implementation plans and informing their approaches to implementation and evaluation. This includes decisions about what data to gather to describe and explain implementation, their hypotheses about action steps needed, how to account for the critical role of context, and providing a foundation for analysis and discussion [7]. The advancement of theoretically informed implementation science will, however, depend on much improved descriptions as to why and how a certain framework was used, and an enhanced and better-informed critical reflection of the functionality of that framework. This review shows that the PARIHS framework has rarely been used as a whole; rather, certain elements tend to be applied, often retrospectively as indicated in Fig. 3 underlining the use of PARIHS in the evaluation of study findings, which resonates with the findings of reviews about the use of the KTA [2] and CFIR [11] frameworks. This could be as a result of a lack of theoretical coherence of some frameworks making them difficult to apply holistically, and/or a function of a general challenge that researchers face in operationalizing theory. However, this could also be a result of publishing constraints. While the PARIHS framework may have guided implementation or been implicitly used in the study design, it was rarely the focus of the publications. Further, the aims and scopes of scientific health care journals have historically prioritized clinical outcomes over implementation outcomes where one could expect a more detailed description of the use of theoretical frameworks. This may have resulted in authors not fully reporting their use of, e.g., the PARIHS framework.

The number of empirical studies using the PARIHS framework has steadily increased over the review period. There is also evidence to show that more research teams have contributed to critiquing the framework in terms of reporting on its strengths and limitations and its validity. The pattern of investigation is moving from studies on context, to more systematic explorations of facilitation, thus contributing to a more detailed understanding of the elements and sub-elements of the framework. The lack of focus on “evidence” identified in this review highlights the need for researchers and clinicians to focus on the multi-dimensionality of what is being implemented. Common patterns emerging in this review support the changes made to the most recent refinement of the PARIHS framework [359].

Consistent with other reviews of the use of theoretical frameworks in implementation science, we found that PARIHS was often not used as intended. Further, it was not always clear why the particular framework was chosen. Frequently, authors merely cite a framework without providing any further information about how the framework was used. The lack of clear guidance on how to operationalize frameworks might be one of the underlying reasons for this. Lastly, to enable a critical review of frameworks and further build collective understanding of implementation, we urge authors to be more explicit about how theory informs studies. Development and adoption of reporting guidelines on how framework(s) are used in implementation studies might assist in sharpening the link between the used framework(s) and the individual study, but could potentially also enhance the opportunities for advancing the scientific understanding of implementation.

Limitations

To increase study reliability during the review process, more than one person identified, assessed, and interpreted the data. We had regular meetings to discuss potential difficulties in assessing included articles, and subsequently, all decisions were resolved by consensus to enhance rigor. We used a rigorous search strategy, which was undertaken by an information specialist. The standardization of our processes across the team was also enhanced by the creation of an online data extraction form via Google. However, as the form was not linked to other software (e.g., Endnote), this added time-consuming processes.

As we did not include articles that were not written in English, we may have limited the insights about the application of the PARIHS framework, particularly with relevance to different country contexts. Additionally, we did not search the grey literature for practical reasons concerning the size of the literature, which may also have provided some additional insights not reflected in this publication. We also limited our search to two databases, which may mean we missed some relevant articles. However, we are confident that we found the majority of relevant published evidence to address the review questions because of a rigorous approach to retrieval. Thus, we think the findings of our citation analysis on the use of PARIHS are generalizable for studies in English published in peer-reviewed journals.

Conclusions

The importance of theoretically underpinned implementation science has been consistently highlighted. Theory is important for maximizing the chances of study transferability, providing an explanation of implementation processes, developing and tailoring implementation interventions, evaluating implementation, and explaining outcomes. This review of the use of the PARIHS framework, one of the most cited implementation frameworks, shows that its actual use and application has been frequently partial and generally not well described. Our ability to advance the science of implementation and ultimately affect outcomes will, in part, be dependent on better use of theory. Therefore, it is incumbent on theory developers to generate accessible and applicable theories, frameworks, and models, and for theory users to operationalize these in a considered and transparent way. We propose that the development and adoption of reporting guidelines on how framework(s) are used in implementation studies might enhance the maturity of implementation science.

Availability of data and materials

The datasets generated and analyzed during the current study can be obtained through contacting the first author.

References

Skolarus TA, Lehmann T, Tabak RG, Harris J, Lecy J, Sales AE. Assessing citation networks for dissemination and implementation research frameworks. Implement Sci. 2017;12(1):97.

Nilsen P. Making sense of implementation theories, models and frameworks. Implement Sci. 2015;10(1):53.

Tabak RG, Khoong EC, Chambers DA, Brownson RC. Bridging research and practice: models for dissemination and implementation research. Am J Prev Med. 2012;43(3):337–50.

Birken SA, Powell BJ, Shea CM, Haines ER, Alexis Kirk M, Leeman J, et al. Criteria for selecting implementation science theories and frameworks: results from an international survey. Implement Sci. 2017;12(1):124.

Kitson A, Harvey G, McCormack B. Enabling the implementation of evidence based practice: a conceptual framework. Qual Health Care. 1998;7(3):149–58.

Rogers EM. Diffusion of Innovations. 5th ed. New York: The Free Press; 2003.

Rycroft-Malone J, Bucknall T. Models and frameworks for implementing evidence-based practice: linking evidence to action. Oxford: John Wiley & Sons; 2010.

Rycroft-Malone J, Kitson A, Harvey G, McCormack B, Seers K, Titchen A, et al. Ingredients for change: revisiting a conceptual framework. Qual Saf Health Care. 2002;11(2):174–80.

Rycroft-Malone J, Harvey G, Seers K, Kitson A, McCormack B, Titchen A. An exploration of the factors that influence the implementation of evidence into practice. J Clin Nurs. 2004;13(8):913–24.

Harvey G, Kitson A. Implementing evidence-based practice in healthcare: a facilitation guide: Routledge; 2015.

Field B, Booth A, Ilott I, Gerrish K. Using the Knowledge to Action Framework in practice: a citation analysis and systematic review. Implement Sci. 2014;9:172.

Kirk MA, Kelley C, Yankey N, Birken SA, Abadie B, Damschroder L. A systematic review of the use of the Consolidated Framework for Implementation Research. Implement Sci. 2016;11:72.

Helfrich CD, Damschroder LJ, Hagedorn HJ, Daggett GS, Sahay A, Ritchie M, et al. A critical synthesis of literature on the Promoting Action on Research Implementation in Health Services (PARIHS) framework. Implement Sci. 2010;5(1):82.

Moher D, Liberati A, Tetzlaff J, Altman DG, Group P. Preferred reporting items for systematic reviews and meta-analyses: the PRISMA statement. PLoS Med. 2009;6(7):e1000097.

Sandelowski M. Real qualitative researchers do not count: the use of numbers in qualitative research. Res Nurs Health. 2001;24(3):230–40.

Graneheim UH, Lindgren BM, Lundman B. Methodological challenges in qualitative content analysis: A discussion paper. Nurse Educ Today. 2017;56:29–34.

Elo S, Kyngas H. The qualitative content analysis process. J Adv Nurs. 2008;62(1):107–15.

Kitson AL, Rycroft-Malone J, Harvey G, McCormack B, Seers K, Titchen A. Evaluating the successful implementation of evidence into practice using the PARiHS framework: theoretical and practical challenges. Implement Sci. 2008;3(1):1.

Harvey G, Loftus-Hills A, Rycroft-Malone J, Titchen A, Kitson A, McCormack B, et al. Getting evidence into practice: the role and function of facilitation. J Adv Nurs. 2002;37(6):577–88.

Rycroft-Malone J. The PARIHS framework--a framework for guiding the implementation of evidence-based practice. J Nurs Care Qual. 2004;19(4):297–304.

Rycroft-Malone J, Seers K, Titchen A, Harvey G, Kitson A, McCormack B. What counts as evidence in evidence-based practice? J Adv Nurs. 2004;47(1):81–90.

McCormack B, Kitson A, Harvey G, Rycroft-Malone J, Titchen A, Seers K. Getting evidence into practice: the meaning of 'context'. J Adv Nurs. 2002;38(1):94–104.

Chinman M, Daniels K, Smith J, McCarthy S, Medoff D, Peeples A, et al. Provision of peer specialist services in VA patient aligned care teams: protocol for testing a cluster randomized implementation trial. Implement Sci. 2017;12(1):57.

Gordon EJ, Lee J, Kang RH, Caicedo JC, Holl JL, Ladner DP, et al. A complex culturally targeted intervention to reduce Hispanic disparities in living kidney donor transplantation: an effectiveness-implementation hybrid study protocol. BMC Health Serv Res. 2018;18(1):368.

Roberge P, Fournier L, Brouillet H, Hudon C, Houle J, Provencher MD, et al. Implementing a knowledge application program for anxiety and depression in community-based primary mental health care: a multiple case study research protocol. Implement Sci. 2013;8(1):26.

Blanco-Mavillard I, Bennasar-Veny M, De Pedro-Gomez JE, Moya-Suarez AB, Parra-Garcia G, Rodriguez-Calero MA, et al. Implementation of a knowledge mobilization model to prevent peripheral venous catheter-related adverse events: PREBACP study-a multicenter cluster-randomized trial protocol. Implement Sci. 2018;13(1):100.

Bucknall TK, Harvey G, Considine J, Mitchell I, Rycroft-Malone J, Graham ID, et al. Prioritising Responses Of Nurses To deteriorating patient Observations (PRONTO) protocol: testing the effectiveness of a facilitation intervention in a pragmatic, cluster-randomised trial with an embedded process evaluation and cost analysis. Implement Sci. 2017;12(1):85.

Chouinard MC, Hudon C, Dubois MF, Roberge P, Loignon C, Tchouaket E, et al. Case management and self-management support for frequent users with chronic disease in primary care: a pragmatic randomized controlled trial. BMC Health Serv Res. 2013;13(1):49.

Cully JA, Armento ME, Mott J, Nadorff MR, Naik AD, Stanley MA, et al. Brief cognitive behavioral therapy in primary care: a hybrid type 2 patient-randomized effectiveness-implementation design. Implement Sci. 2012;7(1):64.

Gurung R, Jha AK, Pyakurel S, Gurung A, Litorp H, Wrammert J, et al. Scaling Up Safer Birth Bundle Through Quality Improvement in Nepal (SUSTAIN)-a stepped wedge cluster randomized controlled trial in public hospitals. Implement Sci. 2019;14(1):65.

Owen RR, Drummond KL, Viverito KM, Marchant K, Pope SK, Smith JL, et al. Monitoring and managing metabolic effects of antipsychotics: a cluster randomized trial of an intervention combining evidence-based quality improvement and external facilitation. Implement Sci. 2013;8(1):120.

Powell K, Kitson A, Hoon E, Newbury J, Wilson A, Beilby J. A study protocol for applying the co-creating knowledge translation framework to a population health study. Implement Sci. 2013;8(1):98.

Rycroft-Malone J, Anderson R, Crane RS, Gibson A, Gradinger F, Owen Griffiths H, et al. Accessibility and implementation in UK services of an effective depression relapse prevention programme - mindfulness-based cognitive therapy (MBCT): ASPIRE study protocol. Implement Sci. 2014;9(1):62.

Rycroft-Malone J, Dopson S, Degner L, Hutchinson AM, Morgan D, Stewart N, et al. Study protocol for the translating research in elder care (TREC): building context through case studies in long-term care project (project two). Implement Sci. 2009;4(1):53.

Rycroft-Malone J, Wilkinson JE, Burton CR, Andrews G, Ariss S, Baker R, et al. Implementing health research through academic and clinical partnerships: a realistic evaluation of the Collaborations for Leadership in Applied Health Research and Care (CLAHRC). Implement Sci. 2011;6(1):74.

Kilbourne AM, Almirall D, Eisenberg D, Waxmonsky J, Goodrich DE, Fortney JC, et al. Protocol: Adaptive Implementation of Effective Programs Trial (ADEPT): cluster randomized SMART trial comparing a standard versus enhanced implementation strategy to improve outcomes of a mood disorders program. Implement Sci. 2014;9(1):132.

McGilton KS, Davis A, Mahomed N, Flannery J, Jaglal S, Cott C, et al. An inpatient rehabilitation model of care targeting patients with cognitive impairment. BMC Geriatr. 2012;12:21.

Botti M, Kent B, Bucknall T, Duke M, Johnstone MJ, Considine J, et al. Development of a Management Algorithm for Post-operative Pain (MAPP) after total knee and total hip replacement: study rationale and design. Implement Sci. 2014;9(1):110.

Cadilhac DA, Andrew NE, Kilkenny MF, Hill K, Grabsch B, Lannin NA, et al. Improving quality and outcomes of stroke care in hospitals: protocol and statistical analysis plan for the Stroke123 implementation study. Int J Stroke. 2018;13(1):96–106.

Perez J, Russo DA, Stochl J, Byford S, Zimbron J, Graffy JP, et al. Comparison of high and low intensity contact between secondary and primary care to detect people at ultra-high risk for psychosis: study protocol for a theory-based, cluster randomized controlled trial. Trials. 2013;14(1):222.

Ray-Barruel G, Cooke M, Mitchell M, Chopra V, Rickard CM. Implementing the I-DECIDED clinical decision-making tool for peripheral intravenous catheter assessment and safe removal: protocol for an interrupted time-series study. BMJ Open. 2018;8(6):e021290.

Saint S, Olmsted RN, Fakih MG, Kowalski CP, Watson SR, Sales AE, et al. Translating health care-associated urinary tract infection prevention research into practice via the bladder bundle. Joint Commission Journal on Quality and Patient Safety. 2009;35(9):449–55.

Sampson EL, Feast A, Blighe A, Froggatt K, Hunter R, Marston L, et al. Evidence-based intervention to reduce avoidable hospital admissions in care home residents (the Better Health in Residents in Care Homes (BHiRCH) study): protocol for a pilot cluster randomised trial. BMJ Open. 2019;9(5):e026510.

Seers K, Cox K, Crichton NJ, Edwards RT, Eldh AC, Estabrooks CA, et al. FIRE (Facilitating Implementation of Research Evidence): a study protocol. Implement Sci. 2012;7(1):25.

Skene C, Gerrish K, Price F, Pilling E, Bayliss P. Developing family-centred care in a neonatal intensive care unit: an action research study protocol. J Adv Nurs. 2016;72(3):658–68.

Wallin L, Malqvist M, Nga NT, Eriksson L, Persson LA, Hoa DP, et al. Implementing knowledge into practice for improved neonatal survival; a cluster-randomised, community-based trial in Quang Ninh province. Vietnam. BMC Health Serv Res. 2011;11:239.

Conklin J, Kothari A, Stolee P, Chambers L, Forbes D, Le Clair K. Knowledge-to-action processes in SHRTN collaborative communities of practice: a study protocol. Implement Sci. 2011;6(1):12.

Estabrooks CA, Squires JE, Cummings GG, Teare GF, Norton PG. Study protocol for the translating research in elder care (TREC): building context - an organizational monitoring program in long-term care project (project one). Implement Sci. 2009;4(1):52.

Kitson AL, Schultz TJ, Long L, Shanks A, Wiechula R, Chapman I, et al. The prevention and reduction of weight loss in an acute tertiary care setting: protocol for a pragmatic stepped wedge randomised cluster trial (the PRoWL project). BMC Health Serv Res. 2013;13(1):299.

Noyes JP, Williams A, Allen D, Brocklehurst P, Carter C, Gregory JW, et al. Evidence into practice: evaluating a child-centred intervention for diabetes medicine management. The EPIC Project. BMC Pediatr. 2010;10:70.

Chao MT, Chang A, Reddy S, Harrison JD, Acquah J, Toveg M, et al. Adjunctive acupuncture for pain and symptom management in the inpatient setting: protocol for a pilot hybrid effectiveness-implementation study. J Integr Med. 2016;14(3):228–38.

Hack TF, Ruether JD, Weir LM, Grenier D, Degner LF. Study protocol: addressing evidence and context to facilitate transfer and uptake of consultation recording use in oncology: a knowledge translation implementation study. Implement Sci. 2011;6(1):20.

Stetler CB, Ritchie J, Rycroft-Malone J, Schultz A, Charns M. Improving quality of care through routine, successful implementation of evidence-based practice at the bedside: an organizational case study protocol using the Pettigrew and Whipp model of strategic change. Implement Sci. 2007;2(1):3.

Urquhart R, Porter GA, Grunfeld E, Sargeant J. Exploring the interpersonal-, organization-, and system-level factors that influence the implementation and use of an innovation-synoptic reporting-in cancer care. Implement Sci. 2012;7(1):12.

Watkins V, Nagle C, Kent B, Hutchinson AM. Labouring Together: collaborative alliances in maternity care in Victoria, Australia-protocol of a mixed-methods study. BMJ Open. 2017;7(3):e014262.

De Pedro-Gomez J, Morales-Asencio JM, Bennasar-Veny M, Artigues-Vives G, Perello-Campaner C, Gomez-Picard P. Determining factors in evidence-based clinical practice among hospital and primary care nursing staff. J Adv Nurs. 2012;68(2):452–9.

Slaughter SE, Estabrooks CA, Jones CA, Wagg AS, Eliasziw M. Sustaining Transfers through Affordable Research Translation (START): study protocol to assess knowledge translation interventions in continuing care settings. Trials. 2013;14(1):355.

Eriksson L, Huy TQ, Duc DM, Ekholm Selling K, Hoa DP, Thuy NT, et al. Process evaluation of a knowledge translation intervention using facilitation of local stakeholder groups to improve neonatal survival in the Quang Ninh province. Vietnam. Trials. 2016;17:23.

Eriksson L, Nga NT, Hoa DP, Persson LA, Ewald U, Wallin L. Newborn care and knowledge translation - perceptions among primary healthcare staff in northern Vietnam. Implement Sci. 2011;6(1):29.

Long-Tounsel R, Wilson J, Adams C, Reising DL. Urban and Suburban Hospital System Implementation of Multipoint Access Targeted Temperature Management in Postcardiac Arrest Patients. Therapeutic Hypothermia and Temperature Management. 2014;4(1):43–50.

McWilliam CL, Kothari A, Ward-Griffin C, Forbes D, Leipert B, South West Community Care Access Centre Home Care C. Evolving the theory and praxis of knowledge translation through social interaction: a social phenomenological study. Implement Sci. 2009;4(1):26.

Obrecht JA, Van Hulle VC, Ryan CS. Implementation of evidence-based practice for a pediatric pain assessment instrument. Clin Nurse Spec. 2014;28(2):97–104.

Allen M, Hall L, Halton K, Graves N. Improving hospital environmental hygiene with the use of a targeted multi-modal bundle strategy. Infection Disease & Health. 2018;23(2):107–13.

Bahtsevani C, Idvall E. To Assess Prerequisites Before an Implementation Strategy in an Orthopaedic Department in Sweden. Orthop Nurs. 2016;35(2):100–7.

Bamford D, Rothwell K, Tyrrell P, Boaden R. Improving care for people after stroke: how change was actively facilitated. J Health Organ Manag. 2013;27(5):548–60.

Brenner LA, Breshears RE, Betthauser LM, Bellon KK, Holman E, Harwood JE, et al. Implementation of a suicide nomenclature within two VA healthcare settings. J Clin Psychol Med Settings. 2011;18(2):116–28.

Brown D, McCormack B. Exploring psychological safety as a component of facilitation within the Promoting Action on Research Implementation in Health Services framework. J Clin Nurs. 2016;25(19-20):2921–32.

Diffin J, Ewing G, Harvey G, Grande G. Facilitating successful implementation of a person-centred intervention to support family carers within palliative care: a qualitative study of the Carer Support Needs Assessment Tool (CSNAT) intervention. BMC Palliat Care. 2018;17(1):129.

Diffin J, Ewing G, Harvey G, Grande G. The Influence of Context and Practitioner Attitudes on Implementation of Person-Centered Assessment and Support for Family Carers Within Palliative Care. Worldviews Evid Based Nurs. 2018;15(5):377–85.

Drainoni ML, Koppelman EA, Feldman JA, Walley AY, Mitchell PM, Ellison J, et al. Why is it so hard to implement change? A qualitative examination of barriers and facilitators to distribution of naloxone for overdose prevention in a safety net environment. BMC Res Notes. 2016;9(1):465.

Ellis I, Howard P, Larson A, Robertson J. From workshop to work practice: An exploration of context and facilitation in the development of evidence-based practice. Worldviews Evid Based Nurs. 2005;2(2):84–93.

Gerrish K, Laker S, Taylor C, Kennedy F, McDonnell A. Enhancing the quality of oral nutrition support for hospitalized patients: a mixed methods knowledge translation study (The EQONS study). J Adv Nurs. 2016;72(12):3182–94.

Gesthalter YB, Koppelman E, Bolton R, Slatore CG, Yoon SH, Cain HC, et al. Evaluations of Implementation at Early-Adopting Lung Cancer Screening Programs: Lessons Learned. Chest. 2017;152(1):70–80.

Harris M, Jones P, Heartfield M, Allstrom M, Hancock J, Lawn S, et al. Changing practice to support self-management and recovery in mental illness: application of an implementation model. Aust J Prim Health. 2015;21(3):279–85.

Harvey G, McCormack B, Kitson A, Lynch E, Titchen A. Designing and implementing two facilitation interventions within the 'Facilitating Implementation of Research Evidence (FIRE)' study: a qualitative analysis from an external facilitators' perspective. Implement Sci. 2018;13(1):141.

Houle SK, Charrois TL, Faruquee CF, Tsuyuki RT, Rosenthal MM. A randomized controlled study of practice facilitation to improve the provision of medication management services in Alberta community pharmacies. Res Social Adm Pharm. 2017;13(2):339–48.

Jangland E, Gunningberg L. Improving patient participation in a challenging context: a 2-year evaluation study of an implementation project. J Nurs Manag. 2017;25(4):266–75.

Lewis A, Kitson A, Harvey G. Improving oral health for older people in the home care setting: An exploratory implementation study. Australas J Ageing. 2016;35(4):273–80.

Lindsay JA, Kauth MR, Hudson S, Martin LA, Ramsey DJ, Daily L, et al. Implementation of video telehealth to improve access to evidence-based psychotherapy for posttraumatic stress disorder. Telemed J E Health. 2015;21(6):467–72.

Mekki TE, Oye C, Kristensen B, Dahl H, Haaland A, Nordin KA, et al. The inter-play between facilitation and context in the promoting action on research implementation in health services framework: A qualitative exploratory implementation study embedded in a cluster randomized controlled trial to reduce restraint in nursing homes. J Adv Nurs. 2017;73(11):2622–32.

Parlour R, McCormack B. Blending critical realist and emancipatory practice development methodologies: making critical realism work in nursing research. Nurs Inq. 2012;19(4):308–21.

Persson LA, Nga NT, Malqvist M, Thi Phuong Hoa D, Eriksson L, Wallin L, et al. Effect of Facilitation of Local Maternal-and-Newborn Stakeholder Groups on Neonatal Mortality: Cluster-Randomized Controlled Trial. PLoS Med. 2013;10(5):e1001445.

Rycroft-Malone J, Fontenla M, Bick D, Seers K. Protocol-based care: Impact on roles and service delivery. Journal of Evaluation in Clinical Practice. 2008;14(5):867–73.

Rycroft-Malone J, Seers K, Crichton N, Chandler J, Hawkes CA, Allen C, et al. A pragmatic cluster randomised trial evaluating three implementation interventions. Implement Sci. 2012;7(1):80.

Rycroft-Malone J, Seers K, Chandler J, Hawkes CA, Crichton N, Allen C, et al. The role of evidence, context, and facilitation in an implementation trial: implications for the development of the PARIHS framework. Implement Sci. 2013;8(1):28.

Rycroft-Malone J, Seers K, Eldh AC, Cox K, Crichton N, Harvey G, et al. A realist process evaluation within the Facilitating Implementation of Research Evidence (FIRE) cluster randomised controlled international trial: an exemplar. Implement Sci. 2018;13(1):138.

Slaughter SE, Estabrooks CA. Optimizing the mobility of residents with dementia: a pilot study promoting healthcare aide uptake of a simple mobility innovation in diverse nursing home settings. BMC Geriatr. 2013;13(1):110.

Sving E, Fredriksson L, Gunningberg L, Mamhidir AG. Getting evidence-based pressure ulcer prevention into practice: a process evaluation of a multifaceted intervention in a hospital setting. J Clin Nurs. 2017;26(19-20):3200–11.

Walsh K, Ford K, Morley C, McLeod E, McKenzie D, Chalmers L, et al. The Development and Implementation of a Participatory and Solution-Focused Framework for Clinical Research: a case example. Collegian. 2017;24(4):331–8.

Mignogna J, Hundt NE, Kauth MR, Kunik ME, Sorocco KH, Naik AD, et al. Implementing brief cognitive behavioral therapy in primary care: A pilot study. Transl Behav Med. 2014;4(2):175–83.

Alkema GE, Frey D. Implications of translating research into practice: a medication management intervention. Home Health Care Serv Q. 2006;25(1-2):33–54.

Kilbourne AM, Abraham KM, Goodrich DE, Bowersox NW, Almirall D, Lai Z, et al. Cluster randomized adaptive implementation trial comparing a standard versus enhanced implementation intervention to improve uptake of an effective re-engagement program for patients with serious mental illness. Implement Sci. 2013;8(1):136.

Mignogna J, Martin LA, Harik J, Hundt NE, Kauth M, Naik AD, et al. "I had to somehow still be flexible": exploring adaptations during implementation of brief cognitive behavioral therapy in primary care. Implement Sci. 2018;13(1):76.

Westergren A. Action-oriented study circles facilitate efforts in nursing homes to "go from feeding to serving": conceptual perspectives on knowledge translation and workplace learning. J Aging Res. 2012;2012:627371.

Baloh J, Zhu X, Ward MM. Types of internal facilitation activities in hospitals implementing evidence-based interventions. Health Care Manage Rev. 2018;43(3):229–37.

Snelgrove-Clarke E, Davies B, Flowerdew G, Young D. Implementing a Fetal Health Surveillance Guideline in Clinical Practice: A Pragmatic Randomized Controlled Trial of Action Learning. Worldviews Evid Based Nurs. 2015;12(5):281–8.

Wallin L, Rudberg A, Gunningberg L. Staff experiences in implementing guidelines for Kangaroo Mother Care--a qualitative study. Int J Nurs Stud. 2005;42(1):61–73.

Bidassie B, Williams LS, Woodward-Hagg H, Matthias MS, Damush TM. Key components of external facilitation in an acute stroke quality improvement collaborative in the Veterans Health Administration. Implement Sci. 2015;10(1):69.

Doran D, Haynes BR, Estabrooks CA, Kushniruk A, Dubrowski A, Bajnok I, et al. The role of organizational context and individual nurse characteristics in explaining variation in use of information technologies in evidence based practice. Implement Sci. 2012;7:122.

Fortney J, Enderle M, McDougall S, Clothier J, Otero J, Altman L, et al. Implementation outcomes of evidence-based quality improvement for depression in VA community based outpatient clinics. Implement Sci. 2012;7(1):30.

Elsborg Foss J, Kvigne K, Wilde Larsson B, Athlin E. A model (CMBP) for collaboration between university college and nursing practice to promote research utilization in students' clinical placements: a pilot study. Nurse Educ Pract. 2014;14(4):396–402.

Johnson S, Ostaszkiewicz J, O'Connell B. Moving beyond resistance to restraint minimization: a case study of change management in aged care. Worldviews Evid Based Nurs. 2009;6(4):210–8.

Kavanagh T, Stevens B, Seers K, Sidani S, Watt-Watson J. Process evaluation of appreciative inquiry to translate pain management evidence into pediatric nursing practice. Implement Sci. 2010;5(1):90.

Kinley J, Stone L, Dewey M, Levy J, Stewart R, McCrone P, et al. The effect of using high facilitation when implementing the Gold Standards Framework in Care Homes programme: a cluster randomised controlled trial. Palliat Med. 2014;28(9):1099–109.

Lewis A, Harvey G, Hogan M, Kitson A. Can oral healthcare for older people be embedded into routine community aged care practice? A realist evaluation using normalisation process theory. Int J Nurs Stud. 2019;94:32–41.

McGilton KS, Sorin-Peters R, Rochon E, Boscart V, Fox M, Chu CH, et al. The effects of an interprofessional patient-centered communication intervention for patients with communication disorders. Appl Nurs Res. 2018;39:189–94.

McLean P, Torkington R, Ratsch A. Development, implementation, and outcomes of post-stroke mood assessment pathways: implications for social workers. Australian Social Work. 2019;72(3):336–56.

O'Halloran PD, Cran GW, Beringer TR, Kernohan G, Orr J, Dunlop L, et al. Factors affecting adherence to use of hip protectors amongst residents of nursing homes--a correlation study. Int J Nurs Stud. 2007;44(5):672–86.

Pallangyo EN, Mbekenga C, Kallestal C, Rubertsson C, Olsson P. "If really we are committed things can change, starting from us": Healthcare providers' perceptions of postpartum care and its potential for improvement in low-income suburbs in Dar es Salaam. Tanzania. Sex Reprod Healthc. 2017;11:7–12.

Pallangyo E, Mbekenga C, Olsson P, Eriksson L, Bergstrom A. Implementation of a facilitation intervention to improve postpartum care in a low-resource suburb of Dar es Salaam. Tanzania. Implement Sci. 2018;13(1):102.

Russell-Babin KA, Miley H. Implementing the best available evidence in early delirium identification in elderly hip surgery patients. Int J Evid Based Healthc. 2013;11(1):39–45.

Rycroft-Malone J, Wilkinson J, Burton CR, Harvey G, McCormack B, Graham I, et al. Collaborative action around implementation in Collaborations for Leadership in Applied Health Research and Care: towards a programme theory. J Health Serv Res Policy. 2013;18(3 Suppl):13–26.

Seers K, Rycroft-Malone J, Cox K, Crichton N, Edwards RT, Eldh AC, et al. Facilitating Implementation of Research Evidence (FIRE): an international cluster randomised controlled trial to evaluate two models of facilitation informed by the Promoting Action on Research Implementation in Health Services (PARIHS) framework. Implement Sci. 2018;13(1):137.

Sigel BA, Kramer TL, Conners-Burrow NA, Church JK, Worley KB, Mitrani NA. Statewide dissemination of trauma-focused cognitive-behavioral therapy (TF-CBT). Children and Youth Services Review. 2013;35(6):1023–9.

Stevens BJ, Yamada J, Promislow S, Barwick M, Pinard M, Pain CTiCs. Pain Assessment and Management After a Knowledge Translation Booster Intervention. Pediatrics. 2016;138(4).

Sving E, Hogman M, Mamhidir AG, Gunningberg L. Getting evidence-based pressure ulcer prevention into practice: a multi-faceted unit-tailored intervention in a hospital setting. Int Wound J. 2016;13(5):645–54.

Tian L, Yang Y, Sui W, Hu Y, Li H, Wang F, et al. Implementation of evidence into practice for cancer-related fatigue management of hospitalized adult patients using the PARIHS framework. PLoS One. 2017;12(10):e0187257.

Tucker SJ, Bieber PL, Attlesey-Pries JM, Olson ME, Dierkhising RA. Outcomes and challenges in implementing hourly rounds to reduce falls in orthopedic units. Worldviews Evid Based Nurs. 2012;9(1):18–29.

Weir C, Brunker C, Butler J, Supiano MA. Making cognitive decision support work: Facilitating adoption, knowledge and behavior change through QI. J Biomed Inform. 2017;71S:S32–S8.

Williams BR, Woodby LL, Bailey FA, Burgio KL. Formative evaluation of a multi-component, education-based intervention to improve processes of end-of-life care. Gerontol Geriatr Educ. 2014;35(1):4–22.

Arslan Yurumezoglu H, Kocaman G. Pilot study for evidence-based nursing management: improving the levels of job satisfaction, organizational commitment, and intent to leave among nurses in Turkey. Nurs Health Sci. 2012;14(2):221–8.

Brosey LA, March KS. Effectiveness of structured hourly nurse rounding on patient satisfaction and clinical outcomes. J Nurs Care Qual. 2015;30(2):153–9.

Chinman M, Acosta J, Ebener P, Burkhart Q, Malone PS, Paddock SM, et al. Intervening with practitioners to improve the quality of prevention: one-year findings from a randomized trial of assets-getting to outcomes. J Prim Prev. 2013;34(3):173–91.

Glegg S. Knowledge brokering as an intervention in paediatric rehabilitation practice. International Journal of Therapy and Rehabilitation. 2010;17(4):203–10.

Harvey G, Oliver K, Humphreys J, Rothwell K, Hegarty J. Improving the identification and management of chronic kidney disease in primary care: lessons from a staged improvement collaborative. Int J Qual Health Care. 2015;27(1):10–6.

Humphreys J, Harvey G, Coleiro M, Butler B, Barclay A, Gwozdziewicz M, et al. A collaborative project to improve identification and management of patients with chronic kidney disease in a primary care setting in Greater Manchester. BMJ Qual Saf. 2012;21(8):700–8.

Kauth MR, Sullivan G, Blevins D, Cully JA, Landes RD, Said Q, et al. Employing external facilitation to implement cognitive behavioral therapy in VA clinics: a pilot study. Implement Sci. 2010;5(1):75.

Almblad AC, Siltberg P, Engvall G, Malqvist M. Implementation of Pediatric Early Warning Score; Adherence to Guidelines and Influence of Context. J Pediatr Nurs. 2018;38:33–9.

Amaya-Jackson L, Hagele D, Sideris J, Potter D, Briggs EC, Keen L, et al. Pilot to policy: statewide dissemination and implementation of evidence-based treatment for traumatized youth. BMC Health Serv Res. 2018;18(1):589.

Anderson DR, Zlateva I, Coman EN, Khatri K, Tian T, Kerns RD. Improving pain care through implementation of the Stepped Care Model at a multisite community health center. J Pain Res. 2016;9:1021–9.

Bailey FA, Williams BR, Woodby LL, Goode PS, Redden DT, Houston TK, et al. Intervention to improve care at life's end in inpatient settings: the BEACON trial. J Gen Intern Med. 2014;29(6):836–43.

Bunch AM, Leasure AR, Carithers C, Burnette RE Jr, Berryman MS Sr. Implementation of a rapid chest pain protocol in the emergency department: A quality improvement project. J Am Assoc Nurse Pract. 2016;28(2):75–83.

Gutmanis I, Snyder M, Harvey D, Hillier LM, LeClair JK. Health Care Redesign for Responsive Behaviours—The Behavioural Supports Ontario Experience: Lessons Learned and Keys to Success. Canadian Journal of Community Mental Health. 2015;34(1):45–63.

McGilton KS, Rochon E, Sidani S, Shaw A, Ben-David BM, Saragosa M, et al. Can We Help Care Providers Communicate More Effectively With Persons Having Dementia Living in Long-Term Care Homes? Am J Alzheimers Dis Other Demen. 2017;32(1):41–50.

Murphy AL, Gardner DM, Kutcher SP, Martin-Misener R. A theory-informed approach to mental health care capacity building for pharmacists. Int J Ment Health Syst. 2014;8(1):46.

Musanti R, O'Keefe T, Silverstein W. Partners in caring: an innovative nursing model of care delivery. Nurs Adm Q. 2012;36(3):217–24.

O'Brien A, Redley B, Wood B, Botti M, Hutchinson AF. STOPDVTs: Development and testing of a clinical assessment tool to guide nursing assessment of postoperative patients for Deep Vein Thrombosis. J Clin Nurs. 2018;27(9-10):1803–11.

Orsted HL, Rosenthal S, Woodbury MG. Pressure ulcer awareness and prevention program: a quality improvement program through the Canadian Association of Wound Care. J Wound Ostomy Continence Nurs. 2009;36(2):178–83.

Rutledge DN, Skelton K. Clinical expert facilitators of evidence-based practice: a community hospital program. J Nurses Staff Dev. 2011;27(5):231–5.

Ryan D, Barnett R, Cott C, Dalziel W, Gutmanis I, Jewell D, et al. Geriatrics, interprofessional practice, and interorganizational collaboration: a knowledge-to-practice intervention for primary care teams. J Contin Educ Health Prof. 2013;33(3):180–9.

Sadasivam RS, Hogan TP, Volkman JE, Smith BM, Coley HL, Williams JH, et al. Implementing point of care "e-referrals" in 137 clinics to increase access to a quit smoking internet system: the Quit-Primo and National Dental PBRN HI-QUIT Studies. Transl Behav Med. 2013;3(4):370–8.

Smith SN, Almirall D, Prenovost K, Liebrecht C, Kyle J, Eisenberg D, et al. Change in patient outcomes after augmenting a low-level implementation strategy in community practices that are slow to adopt a collaborative chronic care model: a cluster randomized implementation trial. Med Care. 2019;57(7):503–11.

Stevens BJ, Yamada J, Estabrooks CA, Stinson J, Campbell F, Scott SD, et al. Pain in hospitalized children: Effect of a multidimensional knowledge translation strategy on pain process and clinical outcomes. Pain. 2014;155(1):60–8.

Tilson JK, Mickan S. Promoting physical therapists' of research evidence to inform clinical practice: part 1--theoretical foundation, evidence, and description of the PEAK program. BMC Med Educ. 2014;14(1):125.

Tistad M, Palmcrantz S, Wallin L, Ehrenberg A, Olsson CB, Tomson G, et al. Developing leadership in managers to facilitate the implementation of national guideline recommendations: a process evaluation of feasibility and usefulness. Int J Health Policy Manag. 2016;5(8):477–86.

Toole BM, Stichler JF, Ecoff L, Kath L. Promoting nurses' knowledge in evidence-based practice: do educational methods matter? J Nurses Prof Dev. 2013;29(4):173–81.

Westergren A, Axelsson C, Lilja-Andersson P, Lindholm C, Petersson K, Ulander K. Study circles improve the precision in nutritional care in special accommodations. Food Nutr Res. 2009;53.

Young A. Institutional interventions to prevent and treat undernutrition. Advanced Nutrition and Dietetics in Nutrition Support2018. p. 176-183.

Balbale SN, Hill JN, Guihan M, Hogan TP, Cameron KA, Goldstein B, et al. Evaluating implementation of methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus (MRSA) prevention guidelines in spinal cord injury centers using the PARIHS framework: a mixed methods study. Implement Sci. 2015;10(1):130.

Bergstrom A, Peterson S, Namusoko S, Waiswa P, Wallin L. Knowledge translation in Uganda: a qualitative study of Ugandan midwives' and managers' perceived relevance of the sub-elements of the context cornerstone in the PARIHS framework. Implement Sci. 2012;7(1):117.

Boblin SL, Ireland S, Kirkpatrick H, Robertson K. Using Stake's qualitative case study approach to explore implementation of evidence-based practice. Qual Health Res. 2013;23(9):1267–75.

Cammer A, Morgan D, Stewart N, McGilton K, Rycroft-Malone J, Dopson S, et al. The hidden complexity of long-term care: how context mediates knowledge translation and use of best practices. Gerontologist. 2014;54(6):1013–23.

Cummings GG, Estabrooks CA, Midodzi WK, Wallin L, Hayduk L. Influence of organizational characteristics and context on research utilization. Nurs Res. 2007;56(4 Suppl):S24–39.

Estabrooks CA, Midodzi WK, Cummings GG, Wallin L. Predicting research use in nursing organizations: a multilevel analysis. Nurs Res. 2007;56(4 Suppl):S7–23.

Estabrooks CA, Squires JE, Cummings GG, Birdsell JM, Norton PG. Development and assessment of the Alberta Context Tool. BMC Health Serv Res. 2009;9:234.

Estabrooks CA, Squires JE, Hayduk LA, Cummings GG, Norton PG. Advancing the argument for validity of the Alberta Context Tool with healthcare aides in residential long-term care. BMC Med Res Methodol. 2011;11:107.

Gagliardi AR, Webster F, Brouwers MC, Baxter NN, Finelli A, Gallinger S. How does context influence collaborative decision-making for health services planning, delivery and evaluation? BMC Health Serv Res. 2014;14:545.

Gibb H. An environmental scan of an aged care workplace using the PARiHS model: assessing preparedness for change. J Nurs Manag. 2013;21(2):293–303.