Abstract

Background

The sustainability of school-based health interventions after external funds and/or other resources end has been relatively unexplored in comparison to health care. If effective interventions discontinue, new practices cannot reach wider student populations and investment in implementation is wasted. This review asked: What evidence exists about the sustainability of school-based public health interventions? Do schools sustain public health interventions once start-up funds end? What are the barriers and facilitators affecting the sustainability of public health interventions in schools in high-income countries?

Methods

Seven bibliographic databases and 15 websites were searched. References and citations of included studies were searched, and experts and authors were contacted to identify relevant studies. We included reports published from 1996 onwards. References were screened on title/abstract, and those included were screened on full report. We conducted data extraction and appraisal using an existing tool. Extracted data were qualitatively synthesised for common themes, using May’s General Theory of Implementation (2013) as a conceptual framework.

Results

Of the 9677 unique references identified through database searching and other search strategies, 24 studies of 18 interventions were included in the review. No interventions were sustained in their entirety; all had some components that were sustained by some schools or staff, bar one that was completely discontinued. No discernible relationship was found between evidence of effectiveness and sustainability. Key facilitators included commitment/support from senior leaders, staff observing a positive impact on students’ engagement and wellbeing, and staff confidence in delivering health promotion and belief in its value. Important contextual barriers emerged: the norm of prioritising educational outcomes under time and resource constraints, insufficient funding/resources, staff turnover and a lack of ongoing training. Adaptation of the intervention to existing routines and changing contexts appeared to be part of the sustainability process.

Conclusions

Existing evidence suggests that sustainability depends upon schools developing and retaining senior leaders and staff that are knowledgeable, skilled and motivated to continue delivering health promotion through ever-changing circumstances. Evidence of effectiveness did not appear to be an influential factor. However, methodologically stronger primary research, informed by theory, is needed.

Trial registration

The review was registered on PROSPERO: CRD42017076320, Sep. 2017.

Similar content being viewed by others

Background

Since the late 1980s, the World Health Organization (WHO) has emphasised schools’ role in promoting health [1, 2]. Increasingly, randomised controlled trials (RCTs) are used to determine the effectiveness of school-based interventions addressing various health outcomes [3,4,5,6,7,8]. While there has been progress in assessing the effectiveness of such interventions [9,10,11], and factors affecting implementation [12,13,14], there is less evidence about sustaining health interventions in schools beyond initial pilots. If effective interventions discontinue, new practices cannot reach wider populations and investments in time, people and resources to initiate and implement them may be wasted [15,16,17,18].

Sustainability is a relatively new area of study [19], and most studies come from health care [19, 20]. Conceptual frameworks for sustainability emphasise complexity, whereby practitioners and other actors individually and collectively engage with intervention components and organisational systems to embed, adapt or discard interventions [21,22,23]. Factors suggested as promoting sustainability include intervention effectiveness, attributes and cost [15, 17, 24]; practitioners’ attributes and activities [21, 24]; the work of intervention champions and organisational leaders [25, 26]; organisational climate and culture; monitoring and evaluation; staff turnover [25, 27]; and the external political and financial climate [26].

While health and education settings may share barriers and facilitators to sustaining new interventions, some factors may differentially affect schools. There may be less political incentive to sustain health interventions; academic education is likely to be prioritised [28,29,30]. Teachers may need more support and preparation time to deliver curriculums that include health [31] and vary in their commitment to teaching health promotion [13, 31]. Limited interaction between schools and the health sector might impede the identification of funding, resources and training for sustainability [30]. Monitoring ongoing effectiveness might be difficult without routine collection of health data [30].

There has been no systematic review of the sustainability of school-based health interventions. Stirman et al.’s systematic review of research on the sustainability of health interventions found 125 empirical studies published 1980 to 2012 but did not focus on particular settings; only 14 studies assessed school-based interventions [20]. Believing a review of school interventions could prove fruitful, we aimed to examine empirical research on the sustainability of health interventions in schools after start-up funding and/or other resources ceased. As the resources available to schools will likely impact on sustainability, we focus on high-income countries only. The review asks: what evidence exists about the sustainability of school-based health interventions? Do schools sustain public health interventions once start-up funds end? What are the barriers and facilitators affecting the sustainability of public-health interventions in schools in high-income countries?

Method

Inclusion/exclusion criteria

A study was included if it:

-

Focused on the (dis)continuation of a school-based public-health intervention within the set of schools originally involved in delivering it, and fieldwork was carried out after external funding and/or other resources to implement the intervention had ended

-

Used qualitative or quantitative empirical methods

-

Was published since 1996 (as these were judged most relevant to current policy contexts) and conducted in an Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD) country

-

The intervention:

-

i.

Had defined components to be delivered

-

ii.

Targeted children aged 5–18 years

-

iii.

Included health outcomes among its primary outcomes

-

iv.

Focused on obesity/overweight/body size; physical activity/sedentary behaviours; nutrition; tobacco, alcohol/drug use; sexual health; mental health/emotional well-being; violence; bullying; infectious diseases; safety/accident prevention; body-image/eating disorders; skin/sun safety; and oral health [10]

-

v.

Was implemented partly/wholly within school during school hours by teachers, pastoral, managerial or administrative staff, health or wellbeing professionals employed by the school or students

-

vi.

Encompassed one or more elements of the Health Promoting Schools (HPS) model [10]: a formal curriculum—health education with allocated class time to help students develop the knowledge, attitudes and skills needed for healthy choices; school ethos or environment—policies or activities outside the curriculum that promote healthy values and attitudes within school; and/or family and/or community engagement—activities engaging families, outside agencies and/or the community

Interventions were excluded if they provided health-information materials only, created new schools or were primarily family/community-based interventions with a minor school component. Interventions which co-located a health service within schools, with services delivered exclusively by clinical providers, were also excluded. The sustainability of such interventions is likely to differ from those delivered partly/wholly by educators or school employees, for example, greater reliance on schools continuing to commission services or the option of service provision at no cost to the school (i.e. through other funding mechanisms), and differences in clinicians and educators’ commitment to sustainability due to differing professional knowledge/roles, peer support and priorities.

Search strategy

We searched electronic databases for English-language publications between January 1996 and September 2017 (PsycINFO, Social Sciences Citation Index – Social Science & Humanities [Web of Science], British Education Index, PubMed, CINAHL, EMBASE and ERIC). A mixture of free-text and controlled terms was searched in titles/abstracts, and MESH headings where relevant. Synonyms for four concepts were combined: sustainability, school, intervention and public health (see Additional file 1 for full terms used). A comprehensive website search was also carried out (see Additional file 2). School-based studies in Stirman et al.’s review were also screened [20]. The references of included studies were checked, and a citation search was conducted on Google Scholar. Subject-matter experts were contacted to identify unpublished/current research, including authors of included studies (see Additional file 3).

Screening

All identified studies were imported into the data-management software EPPI-Reviewer 4 [32]. Fifty articles were initially double-screened by two reviewers (LH, HM) on title/abstract: 94% agreement was achieved and discrepancies were discussed to reach a consensus. Reviewers then worked independently, single-screening on title/abstract. Studies were retained if they met the inclusion criteria or if there was insufficient information in the title/abstract to judge. Full-text copies of potentially relevant papers were retrieved and screened independently by the two reviewers to decide on inclusion. If there was uncertainty, studies were discussed by both reviewers (LH, HM) until a consensus was reached, involving a third reviewer (CB) when necessary.

Data extraction and quality appraisal

We extracted data from each included report on study sample/population; description of the intervention (adapted criteria [33]); key dates, study design/methodology and results for the evaluation of effectiveness (or implementation period for non-evaluated initiatives) and sustainability phase; and information needed for quality appraisal (see Additional file 4). Two reviewers (LH, HM) extracted data from two study reports, comparing their results. Pairs of reviewers (LH, HM or LH, TO) independently completed data extraction for each included report. Differences between reviewers were discussed, including a third reviewer (CB) where necessary.

Two reviewers assessed study reliability using an existing checklist [34]: justification for study focus and methods used; clear aims/objectives; clear description of context, sample and methodology; demonstrated attempts to establishing data reliability and validity; and inclusion of original data. Studies were assigned two ‘weight-of-evidence’ ratings [35], one for reliability and one for relevance to answer the review question, rated ‘low’, ‘medium’ or ‘high’. To achieve ‘high’ reliability, at least five criteria had to be met, for ‘medium’ at least four criteria had to be fully or partially met, and all other studies were rated ‘low’. We also downgraded the reliability of retrospective, cross-sectional studies using self-report data for interventions implemented more than 2 years ago. For a judgement of ‘high’ relevance, studies had to describe, with breadth and depth, factors influencing sustainability and privilege participants’ perspectives (Additional file 5 describes quality criteria and ratings). Studies were not excluded from the synthesis based on their reliability, but greater qualitative weight was given to those assessed as ‘medium’ or ‘high’. The quality-assessment tool was piloted on two studies by each pair of reviewers (LH, HM and LH, TO) with results discussed to ensure consistency. Each included study was then independently quality-assessed by each reviewer with discrepancies discussed, where necessary resolved with a third reviewer (CB).

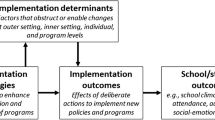

Synthesis of results

We originally intended to use a meta-ethnographic approach as submitted in the protocol [36]. We anticipated finding qualitative studies that were rich in concepts, metaphors and description. However, only one study went beyond description to interpret participants’ views and experiences, and it was not possible to ‘translate’ and synthesise concepts from one study into another. Instead, we conducted thematic synthesis [37] to develop concepts from the mixture of qualitative, quantitative and mixed studies identified. One reviewer (LH) read and re-read studies and carried out line-by-line coding using NVivo 11 software. Inductive codes were developed from the qualitative data (participants’ verbatim quotes and authors’ interpretations) and from authors’ textual reports of quantitative findings. Each code’s data were checked for consistency of interpretation and re-coded as necessary. We used the General Theory of Implementation (GTI [38]) as a sensitising lens; it explains how implementation proceeds over time, building on normalization process theory [21, 39] (Fig. 1 summarises the theory’s constructs). Memos were used to explain codes, their relationships and their alignment with the GTI. GTI informed the overarching structure of themes and sub-themes that was developed. The reliability of each study was checked and referred to as the overall themes were incorporated into a narrative synthesis. The three other reviewers (HM, TO, CB) commented on and discussed a draft of the themes and sub-themes, and a final version was agreed.

This review was registered on PROSPERO (6.9.17, CRD42017076320, [36]) and follows PRISMA reporting standards (Additional File 6).

Results

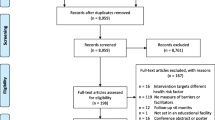

Of the 9670 unique title/abstracts generated through database-searching (see Fig. 2), we included 20 reports of 19 studies. Other search strategies yielded seven additional reports from five studies. Data extraction was completed for these 24 studies; extraction was not conducted on three doctoral theses [40,41,42] because each had a corresponding published paper of the same study included in the review [43,44,45]. In total, the review included 24 studies of 18 different interventions.

Study characteristics

Study origin

Seventeen of the 24 studies were based in the United States (US), of which seven were studies of the Child and Adolescent Trial for Cardiovascular Health (CATCH) intervention [44,45,46,47,48,49,50,51,52,53,54,55,56,57,58,59,60] and the remainder were from Norway [43, 61], the Netherlands [62, 63], Canada [64], England [65] and Germany [66].

Intervention characteristics and effectiveness

The largest group of interventions focused on healthy eating and/or physical activity (n = 10); the remainder targeted anti-social behaviour (n = 2), mental health (n = 2), alcohol/drug use (n = 2), peer and dating violence (n = 1) and workplace health-and-safety (n = 1) (see Table 1). Nine were based in elementary/primary schools, eight in middle/high/secondary schools and one in both settings. Intervention length, as initially funded/implemented, ranged from 8 weeks to 3 years (mode = 1 year); three interventions were of unspecified length.

During initial implementation in schools prior to assessing sustainability, effectiveness evaluations were conducted of 15 interventions; three were not evaluated [53, 62, 63], though one [63] had been assessed by RCT in other schools [75] (see Table 1). Of the effectiveness evaluations, six interventions (relating to 12 studies) were assessed by RCTs [47,48,49, 51, 52, 55, 56, 58, 60, 61, 64, 66], two by using non-randomised controlled studies [59, 65] and seven by uncontrolled evaluations [43,44,45,46, 50, 54, 57]; evaluation reports were inaccessible for three interventions). Of the 12 interventions for which evaluation reports were available, five interventions were effective for all primary outcomes, six interventions were effective for some but not all primary outcomes and one intervention had no effect and a negative effect for one treatment condition (see Table 1).

Study design/methods

Ten studies of sustainability used quantitative cross-sectional designs (42%) [50,51,52,53,54, 56, 59, 60, 64, 66], and one study employed a quantitative longitudinal design [61] (see Table 2). All except one of these used questionnaires to examine sustainability. Six studies employed qualitative designs [43,44,45,46, 48, 58]. Seven studies used mixed-methods [47, 49, 55, 57, 62, 63, 65]. Ten studies (42%) used a comparison group of schools [47,48,49, 51,52,53, 55, 56, 61, 65].

Timeframe examined

Timeframes between the effectiveness evaluation (or implementation period in non-evaluated initiatives) and the study of sustainability varied (Table 1). Five studies examined sustainability less than a year after the effectiveness evaluation [44, 45, 50, 58, 66]. Four were conducted 1 to 2 years later [47, 61, 63, 65]; ten took place 2 to 5 years after the evaluation [47, 49, 50, 52, 53, 56,57,58, 61, 65] and five examined sustainability more than 5 years later [43, 53, 54, 59, 62].

Study participants

Six studies sampled several classroom teachers per school [44, 45, 50, 52, 64, 65], and six of the CATCH studies sampled multiple staff members and/or school-district level personnel per school [48, 49, 51, 55, 56, 60] (see Additional file 7). Three studies sampled school principals only [43, 62, 66], four sampled one teacher or staff-member per school [47, 54, 59, 63] and one sampled clinicians delivering the intervention plus school-district level personnel [46]. Three collected data from students [45, 61, 65], and one interviewed the research team implementing the intervention [45]. Three studies provided no details on staff-level participants [53, 57, 58].

Study quality

Study reliability and relevance varied. On reliability, seven studies were rated high, nine medium and eight low. On relevance for answering the review question, four studies were rated high, ten medium and ten low. Only one study was rated high on relevance and reliability [46] (see Table 2).

Explicit use of conceptual framework

Most studies did not use a conceptual theory/framework. Of those that did (n = 9), a variety of sustainability [17, 76,77,78,79] and implementation frameworks [80,81,82] were used. Only one study [43] drew on conceptual frameworks specific to educational settings [83].

Reporting of sustainability

Eleven studies reported on intervention sustainability at school-level [43, 45, 47, 53, 57, 58, 60,61,62,63, 66], ten at staff-level [44, 46, 48,49,50,51,52, 54, 64, 65], two at the school- and staff-level [55, 56] and one at school-district and school-level [59] (Table 2). Seventy-six percent of studies with a curriculum component [45, 47,48,49,50,51,52,53, 56,57,58, 64, 65], 67% of studies with a school-environment component [43,44,45,46,47, 53, 55, 57, 61, 66] and one third of studies containing a family/community component reported on its sustainability [45, 46, 48, 53] (see Table 3). Around half of studies (46%) of multi-component interventions reported sustainability of some but not all components.

Sustainability of the interventions

No interventions were entirely sustained; Table 3 summarises the percentage of staff or schools sustaining each component. Studies were heterogeneous: all interventions had some components that were continued by some schools or staff, except for one intervention that was completely discontinued two years after the effectiveness evaluation [46]. There were no noticeable patterns between evidence of effectiveness during implementation and sustainability, unaided by inconsistency and gaps in the reporting of sustainability and evidence of effectiveness (see Table 4).

Thematic synthesis of barriers and facilitators of sustainability

Four overarching themes emerged: three themes broadly aligned with three of the four main constructs of the GTI framework (see Fig. 1) and the fourth described the wider policy context (see Table 5). Themes were schools’ capacity to sustain health interventions (GTI construct ‘capacity’), staff’s motivation and commitment (GTI construct ‘potential’), intervention adaptation and integration (GTI construct ‘capability’) and wider policy context for health promotion. We found that the fourth GTI construct of ‘contribution’ was implicated within the other themes (we highlight where this occurs) and comment on this further in the discussion. Themes and sub-themes are described below.

Theme 1: Schools’ capacity to sustain health interventions

Schools’ social norms, staff roles, resources and systems were reported to influence sustainability. Five sub-themes developed from 20 studies of 14 interventions [43,44,45,46,47,48,49, 51,52,53,54,55,56,57,58,59, 63,64,65,66].

-

1.

Educational outcomes took precedence over health promotion

Teachers, principals and administrators prioritised teaching the academic curriculum, meeting educational standards and regulations. Under time constraints, health promotion was considered dispensable, a theme that arose from nine studies (high and medium reliability) of six interventions focused on physical activity, healthy eating and mental health [43, 44, 46, 48, 49, 52, 56, 65]. A district-level informant from the CATCH study commented:

…if you’re going to prioritize, you’re going to prioritize on academics. ...You always concentrate on academics but there was more room for PE and health and those kinds of things before the state kicked in the really extremely rigorous academic standards. ([48], p. 515)

There were some exceptions where principals or administrators encouraged staff to focus on health [43, 46, 48], but the prevailing norm was to focus on academic attainment.

-

2.

Staff members’ roles in sustainability

Staff members’ roles and autonomy were reported to affect whether interventions were sustained at school-level or solely by individual practitioners. Two deeper sub-themes emerged: the importance of the principal and administration, and teachers’ autonomy in the classroom.

-

i)

The importance of the principal and school administration

Commitment and support from the principal and administration (including the school district in US studies) were considered crucial to ‘pave the way’ for sustainability [46], a sub-theme identified in 12 studies of 11 interventions [43, 45,46,47,48, 52,53,54, 59, 63,64,65]. Senior staff had the power to stop or continue an intervention at school-level through authorisation [46, 48], re-distributing school funds to or away from interventions [45, 47], allocating time for delivery [43, 46, 47] and providing training for new staff [43, 47, 63] (see sub-theme 4 (i) ‘Staff turnover’ in the ‘Theme 1: Schools’ capacity to sustain health interventions’ section).

Beyond resources, principals/administrators could demonstrate their commitment through integrating the intervention into school policies [43], recruiting new staff who were well-disposed to it [63], giving staff positive recognition [43, 53, 64] and managing staff to ensure that they continued [43]. The principal had a key role in continuing to enrol staff in a community of practice and persuading staff that it was right for them to address health [43]. This sub-theme overlaps with the GTI domain ‘cognitive participation’ under the construct ‘contribution’.

-

ii)

Teachers’ autonomy in the classroom

Four studies of four interventions (high and medium reliability) indicated that teachers had autonomy to decide whether to sustain interventions in their classroom, within the bounds of the curriculum and principals’ leadership [43, 44, 48, 65]. Other studies revealed that if teachers sustained interventions, they could adapt them as they deemed appropriate (see sub-theme 1 ‘The workability of the intervention’ in the ‘Theme 3: Intervention adaptation and integration’ section). One teacher from a US study of CATCH reported [48]:

It is an individual decision. The state has a framework of what we are supposed to teach. We are asked to teach the things that the district recommends, but if you have more time, you can teach other things as well. No one has asked us to use the CATCH curriculum since the program ended in our school so it was up to us. ([48], p. 509)

There were some examples of collective action among teachers (reflecting GTI domain ‘collective action’ under ‘contribution’). Two US studies (medium and high reliability) of physical-activity interventions showed teachers working together to plan and develop ideas [44] and to encourage the principal to raise funds for sustainability [45]. There was an example of staff receiving logistical support [46] and providing internal training to other staff [48]. The piecemeal evidence for collective action may reflect the lack of attention given to this factor in the studies or a norm that teachers’ work with an intervention beyond the evaluation of effectiveness is typically independent.

-

3.

Funding and material resources

Insufficient funding, equipment, materials and/or physical space could lead to discontinuation, cause logistical challenges [43, 47, 64] or become a reason for adaptation (see sub-theme 1 ‘The workability of the intervention’ in the ‘Theme 3: Intervention adaptation and integration’ section), a sub-theme developed from 16 studies of 11 interventions [45,46,47,48,49, 51, 52, 54,55,56,57,58,59, 63, 64, 66]. A lack of resources could motivate schools to seek out external funds via fundraising, grants or assistance from school-related associations [48, 57, 58, 66], redistribute school budgets [45] or find alternative means such as volunteers or parental payments [47, 57, 66]. As one study (medium reliability) of an all-girls physical-activity intervention reported:

Lack of finances was mentioned as a reason that teachers did not offer guest instructors or hold weekly lunch bunches. Whereas some teachers asked for volunteers to teach yoga or dance, others used videos or asked students to pay a $5 activities fee at the beginning of the class to use for guest instructors’ fees. ([47], p. 5)

-

4.

Cognitive resources

Schools needed to retain the knowledge, skills and experience to sustain the intervention. Two deeper sub-themes emerged related to staff turnover and the importance of training.

-

i)

Staff turnover

Fifteen studies of ten interventions described the adverse impact of staff turnover. As staff left, organisational knowledge, enthusiasm and the co-ordination of the intervention could dissipate [43, 46,47,48,49, 51,52,53, 55, 56, 58, 59, 63,64,65]. A change in principal [43, 48, 63] or loss of a champion (a senior staff member who advocated and assumed responsibility for intervention coordination and integrity) could jeopardise sustainability [46, 58, 62]. New decision-makers did not always share enthusiasm for the intervention or had other priorities, as a clinician from one highly reliable US study of a mental-health intervention explained:

We’ve lost a major senior administrator that is proactive and advocated for the kids’ needs, across the board, regular education and special education. Things have changed. Within the last year, they’re just looking at all the academics right now. ([46], p. 138)

-

ii)

The importance of training

A lack of training for new teachers or booster training was a barrier to sustainability, a sub-theme emerging from 12 studies of nine interventions [43, 46,47,48,49, 51,52,53, 56, 59, 64, 65]. One Dutch study (medium reliability) of an intervention to reduce aggressive behaviour found a designated school co-ordinator to train and coach teachers facilitated sustainability [63]. As well as giving staff the skills and knowledge for delivery, training could generate enthusiasm and communicate the intervention’s philosophy [47, 48], as described by a teacher from a US study (medium reliability) of CATCH:

The staff development was interesting and motivated teachers. They learned about nutrition and fitness. They got excited about it and therefore implemented it. And that made it difficult to implement in schools that had not had the training. They missed a real motivational surge and missed looking at the importance and hearing from experts. ([48], p. 515)

-

5.

Social resources

Schools’ networks with other schools, community organisations and funding agencies appeared to influence sustainability, a sub-theme emerging from four studies (high, medium and low reliability) of four interventions [43, 45, 48, 58]. Strong social links could give schools access to funding [58] and training [48], and collaborations with community organisations and other schools could motivate schools to maintain and develop interventions [43].

Theme 2: Staff motivation and commitment

Five sub-themes emerged on staff motivation and commitment to sustain health interventions from 18 studies of 15 interventions [43,44,45,46,47,48,49,50, 52, 53, 55, 59, 60, 62,63,64,65,66].

-

1.

Observing and evaluating effectiveness

Directly observing the benefits for students’ engagement, wellbeing and behaviour was a strong motivator to continue [43,44,45,46,47,48,49,50, 52, 63, 65, 66]. No staff referred to the findings of the effectiveness evaluation when discussing the intervention’s value, though a clinician in one study commented seeing a change in students based on a ‘pre and post test’ [46]. Conversely, negative responses from students could be a barrier [48, 55, 64]. For example, a teacher from a Dutch study (medium reliability) of an intervention to reduce aggressive behaviour reported:

It gives the team power. And, especially now, with more children with behavioral problems in the classroom. When you stay on the positive side, almost all children will get along. ([63], p. 85)

Two studies (high reliability) asked students about their experiences of physical activity interventions [45, 65] and found they had little decision-making power over what activities were sustained; they were willing participants, but opportunities were largely dictated by their families or the school. For example, a student commented on a component discontinued due to time constraints (as reported by teachers):

Taylor said, ‘We started these warmups, and then they stopped. I don’t know why, but I wish we had them. It is hard to run the CV day with no warmup.’ ([65], p. 114)

Only four studies (one high, two medium and one low reliability) of four interventions referred to more formal processes to appraise effectiveness [43, 46, 59, 63], overlapping with the GTI domain of ‘reflexive monitoring’ under ‘contribution’. Two studies found no differences in sustainability between schools with procedures for reviewing the intervention and those without [59, 63]. One study (medium reliability) reported principals who sustained the intervention regularly evaluated health-promotion activities.

-

2.

Staff confidence in delivering health promotion

Staff who had been trained in the intervention felt more confident and better prepared to deliver it [47,48,49, 52, 64] (see sub-theme 4 (ii) ‘The importance of training’ in the ‘Theme 1: Schools’ capacity to sustain health interventions’ section). Teachers delivering an intervention outside of their usual expertise were less likely to sustain it [43, 47,48,49,50, 64, 65], for example, PE teachers delivering nutrition education [47] or classroom teachers delivering PE [43, 48,49,50, 65]:

Among classroom teachers, feeling inadequately prepared to implement PE was frequently reported; and in many cases, teachers had little interest in gaining the skill. ([49], p. 471)

-

3.

Parent support

Five studies noted parent support in a general sense was helpful [43, 45, 52, 59, 64]. Four studies covered parent support in more depth; staff indicated how lack of parent support could reduce their motivation to sustain an intervention [46, 48, 62, 65]. This sub-theme overlaps with the GTI domain ‘coherence’ under ‘contribution’. A teacher from an English study (high reliability) of a physical-activity intervention explained:

I think a lot of it is home life, if the parents don’t push them towards sporting activities then you’re fighting a battle straight away in school. ([65], p. 8)

-

4.

Believing in the importance of the intervention

Belief in the importance of the intervention motivated staff to sustain it, a sub-theme arising from seven studies of six interventions [43, 44, 46,47,48,49, 52, 63] and was related to the importance of training (sub-theme 4 (ii) ‘The importance of training’ in the ‘Theme 1: Schools’ capacity to sustain health interventions’ section) and observing intervention effectiveness (sub-theme 1 ‘Observing and evaluating effectiveness’ in the ‘Theme 2: Staff motivation and commitment’ section). Principals who reported sustaining a 3-year HPS intervention in Norway, which aimed to create a positive school environment for health, were keen to communicate its importance:

School satisfaction and safety are at the bottom of this school. It is under the teachers’ skin and in our walls. We work with this no matter what is on our agenda. ([43], p. 59)

-

5.

The impact of school climate

There was limited evidence on the impact of staff perception of the school climate. One highly reliable US study of CATCH suggested climate might differentially impact on different interventions: a positive climate was associated with more teaching hours of the CATCH curriculum but higher levels of saturated fat in school meals [60]. Respondents in two other studies (medium and high reliability) reported that a negative climate meant that sustainability processes were superseded by more critical organisational priorities [46, 63]. One US study (low reliability) of a workplace health-and-safety intervention found no relationship between climate and sustainability.

Theme 3: Intervention adaptation and integration

Schools’ ability to sustain an intervention was affected by its ‘workability’—the degree to which it could be shaped into existing school practices and routines, and its integration into school policies and plans. These two sub-themes emerged from 18 studies of 13 interventions [43,44,45,46,47,48,49, 52,53,54,55,56, 58, 60, 63,64,65,66].

-

1.

The workability of the intervention

Three deeper sub-themes transpired: fitting the intervention into the time available, matching the intervention to students’ needs and the need for up-to-date equipment and materials.

-

i)

Fitting the intervention into the time available

Frequently, staff identified that interventions required too much time, time which was primarily devoted to delivering the curriculum (see sub-theme 1 ‘Educational outcomes took precedence over health promotion’ in the ‘Theme 1: Schools’ capacity to sustain health interventions’ section) [44,45,46, 48, 49, 52,53,54,55,56, 63,64,65]. Staff dealt with time constraints by reducing or dropping components [45, 47, 64, 65], or making time for the intervention by adapting it to classroom routines [44, 50] or incorporating elements of it into the existing curriculum [48, 52, 53, 56, 58, 65].

-

ii)

Matching the intervention to students’ needs

Adaptation was also important to match the needs of different cohorts of students, to offer the intervention to different grades [53, 63], better fit students’ learning abilities or make lessons more contextually relevant [43, 54], devote more time to particular activities to ensure students understood a subject or better engage students [46, 64].

-

iii)

The need for up-to-date materials

Over time, new equipment and materials were needed as equipment grew worn or was lost [49], materials became dated [48, 53, 64], new technological advances emerged [50, 64] or adaptations were needed to meet students’ needs [53, 54, 64].

-

2.

Integration of the intervention with school policies and plans

One Dutch study of an intervention to reduce aggressive behaviour and one Norwegian study of an HPS intervention (medium reliability) reported that schools with greater sustainability more often made reference to it in school policies or plans [43, 63]. Studies suggested formal documentation signalled principals’ and administrators’ commitment to the intervention [63], legitimised it [48, 63], made staff accountable [43] or made the intervention resilient to staff turnover [43] (see sub-theme 4 (i) ‘Staff turnover’ in the ‘Theme 1: Schools’ capacity to sustain health interventions’).

Theme 4: Wider policy context for health promotion

The wider policy context could also affect sustainability, a thematic area positioned outside of the GTI framework, emerging from seven studies of five interventions. Regional or national health policies could support sustainability by legitimising health promotion in schools’ policies [43, 48] (see sub-theme 1 ‘Educational outcomes took precedence over health promotion’ in the ‘Theme 1: Schools’ capacity to sustain health interventions’ section). Over time, health policies could shape social norms: for example, increasing tobacco-control regulations could enhance the sustainability of outdoor-smoking bans in schools [62]. Policy could also provide funding and resources [55, 57], though additional resources could also lead to competing interventions, potentially displacing existing ones [55, 56].

Discussion

Summary of key findings

The sustainability of public health interventions after start-up funding and/or other resources end has been relatively uncharted in schools compared to health care. We identified 24 studies assessing the sustainability of school-based health interventions delivered partly/wholly by educators or school-employed health professionals, but quality was not consistently high. None of the interventions assessed were fully sustained; all had components sustained by some schools or staff, bar one that was completely discontinued. Identifying common facilitators and barriers could help researchers and providers optimise the sustainability of school interventions, and consider whether/how the intervention is likely to have a lasting impact on student and staff health. Two key facilitators emerged. First is the central importance of a committed principal and administration that could authorise continuation, allocate resources, integrate the intervention into school policies and enrol new staff into a community of practice. Second is the importance of supporting staff who are confident in delivering health promotion and believe in its value. These facilitators are consistent with studies of the implementation of school health interventions [13, 31, 67], suggesting factors are crucial to both phases.

Many of the facilitators and barriers to sustainability identified for school settings were similar to those in health care: for example, dedicated leaders, the need for continued resources and training, staff turnover and intervention workability [21, 24,25,26,27]. Several factors were more salient for schools. Health encompasses multiple outcomes, some of which may be more obviously relevant to school settings. We identified the sub-theme of educational outcomes taking precedence over physical activity, nutrition and mental health interventions, but not for those focused on anti-social or violent behaviour. This suggests that throughout adoption and implementation, change agents need to convince schools that health interventions can bring education benefits [30, 68,69,70].

Student engagement was key to implementation and sustainability at teacher-level. A central role of educators is to engage students [29, 71], and staff were unlikely to sustain interventions that did not draw students in [48]. Sometimes sustainability was prompted by students’ requests for the intervention [44, 45]. Knowing parents encouraged the healthy activities of the intervention outside of school also motivated staff to continue, further supporting the view that schools are complex adaptive systems, where multiple networks of agents act and react to one another [30]. In contrast, only 16% of the 62 sustainability approaches in Lennox et al.’s review [23] included patient involvement, suggesting that most existing tools and frameworks for health care settings do not consider patient support for the intervention critical for sustainability.

Also of particular significance for schools was the need to adapt intervention materials and activities to accommodate other curriculum requirements and the diversity of children’s backgrounds and development [29, 72]. This dynamic context suggests that intervention developers should anticipate the need for adaptation, even for effective, well-implemented and funded school health interventions [21, 30, 73].

Contrary to other studies of sustainability in health care settings [20], we found little evidence that champions helped sustain interventions: like other staff, champions moved to new institutions leaving interventions at risk. We found no discernible relationship between evidence of effectiveness and sustainability, and no school staff mentioned outcome evaluation as an influential factor in sustainability.

Strengths and limitations

Our review was comprehensive and rigorously conducted. It is the first to apply the GTI to the study of sustainability. We found the framework helpful in creating a balance between listing the common enablers and barriers and representing the complexity and context-dependent nature of sustainability in schools. The data aligned well with the constructs of capacity (theme 1), potential (theme 2) and capability (theme 3), while the construct of contribution was implicated within the other themes. It made sense to consider ‘cognitive participation’ and ‘collective action’ under the construct of ‘capacity’ as the ongoing enrolment of staff, the legitimisation of health activities, and whether staff worked independent or collectively appeared significantly affected by schools’ social norms and roles. Under capacity, we included an additional domain of ‘social resources’ which suggested that contact between schools and other organisations could facilitate sustainability through creating opportunities for resource- and knowledge-sharing, while stimulating ongoing interest in the intervention.

Regarding limitations, we did not double-screen full reports and we may have missed reports due to the array of terms used to describe sustainability, despite our sensitive search strategy. We deviated from our original protocol in using thematic synthesis rather than meta-ethnography due to the nature of studies found. We excluded interventions delivered by clinical services co-located in schools, and consequently, our findings may be less representative of the sustainability of targeted or tiered services which typically require a high level of clinical expertise (only 3 of the 24 interventions in the review were targeted). The sustainability of health interventions provided solely by external clinicians is unknown; for example, they could be more sustainable because they do not require educators to expend time gaining additional knowledge and skills, or they may be less because they require sustained funding. There was substantial heterogeneity in study designs, methods and reporting of included studies; many studies were methodologically weak and did not report on the sustainability of all components, in particular reporting for family/community components was poor. Most studies were located in the US, and consequently, our review findings may be most relevant to this setting. Around half of interventions focused on healthy eating/physical activity, with a lack of evidence for the sustainability of other public-health interventions.

Implications for research and policy

Informed by our synthesis, we propose three questions to consider when optimising school health interventions. First, is it important that each component is sustained? Some components, such as needs assessment, may be time-limited stepping-stones. Second (if a component is to be sustained), how would you expect the intervention to be sustained: if there were high staff turnover or the loss of the champion, during time-pressured periods such as exams, with different classes of students with varying needs or if there were no opportunities for regular training updates? Third, do staff understand the key theoretical principles that should underpin any adaptations to intervention activities and resources? Creating forums during the period of the evaluation of effectiveness when these ‘stress-testing’ questions can be discussed with staff could help researchers to understand the likely sustainability of interventions.

Stronger study designs/methodology are needed for future research; there were few longitudinal studies prospectively following intervention sustainability from initial implementation. Increased use of conceptual theory would enhance studies’ richness and breadth and improve the analytic generalisability of findings. Student engagement in the intervention should be considered a key factor affecting both implementation and sustainability processes. The inclusion of views from a range of school participants, including students, would strengthen the validity of findings. Improved reporting on sustainability of all intervention components is key, with justification provided for excluding specific components. Research on the sustainability of interventions outside health eating/physical activity is needed, for example, there were no studies of sexual-health interventions, as are studies of the sustainability of interventions delivered by external providers co-located in schools.

Sustainability strategies contributed to our analysis where authors commented on them in papers’ results and discussions [43,44,45, 52, 64]. However, several papers referred to specific sustainability strategies in their background sections but did not consider their impact in their analysis of sustainability, including ‘train-the-trainer’ models to spread the intervention across and between schools [58, 63], external consultants exploring adaptations with staff [53] and a staged-approach to implementation [50]. Primary research on the impact of implementation and sustainability strategies and planning would be valuable [74, 84].

Our review suggests regional and/or national school policies and educational standards that promote health and wellbeing and its connection to students’ learning and school enjoyment could enhance sustainability by legitimising staff spending time, effort and resources on continuation, as well as bringing funding and resources to sustain health goals.

Conclusion

Multiple factors facilitating and prohibiting schools’ ability to sustain health interventions emerged from the review, and existing evidence suggests sustainability depends upon schools developing and retaining senior leaders and staff that are knowledgeable, skilled and motivated to continue delivering health promotion through ever-changing circumstances. Evidence of intervention effectiveness did not appear to be an influential factor. However, there is a significant gap in our understanding of how to sustain interventions and methodologically stronger primary research, informed by theory, is needed.

Availability of data and materials

The data extraction forms used and analysed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

Abbreviations

- ASAP:

-

Adolescent Suicide Awareness Program

- BMI:

-

Body mass index

- CATCH:

-

Child and Adolescent Trial for Cardiovascular Health

- CBITS:

-

Cognitive Behavioral Intervention for Trauma in Schools

- F&V:

-

Fruit and vegetables

- GBG:

-

Good Behavior Game

- GTI:

-

General Theory of Implementation

- HOPE:

-

Health Optimizing PE

- HPS:

-

Health Promoting Schools

- MVPA:

-

Moderate-to-Vigorous Physical Activity

- OECD:

-

Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development

- PA:

-

Physical activity

- PDV:

-

Physical dating violence

- PE:

-

Physical education

- PTSD:

-

Post-traumatic stress disorder

- WHO:

-

World Health Organization

References

WHO. Ottawa Charter for Health Promotion. Ottawa: World Health Organization; 1986. http://www.euro.who.int/__data/assets/pdf_file/0004/129532/Ottawa_Charter.pdf?ua=1

WHO. Promoting health through schools: report of a WHO expert committee on comprehensive school health education and promotion. Geneva: World Health Organization; 1997.

Brown T, Summerbell C. Systematic review of school-based interventions that focus on changing dietary intake and physical activity levels to prevent childhood obesity: an update to the obesity guidance produced by the National Institute for Health and Clinical Excellence. Obes Rev. 2009;10:110–41.

Kriemler S, Meyer U, Martin E, van Sluijs EMF, Andersen LB, Martin BW. Effect of school-based interventions on physical activity and fitness in children and adolescents: a review of reviews and systematic update. Br J Sports Med. 2011;45:923–30.

Cuijpers P. Effective ingredients of school-based drug prevention programs. Addict Behav. 2002;27:1009–23.

Denford S, Abraham C, Campbell R, Busse H. A comprehensive review of reviews of school-based interventions to improve sexual-health. Health Psychol Rev. 2017;11:33–52.

Vreeman RC, Carroll AE. A systematic review of school-based interventions to prevent bullying. Arch Pediatr Adolesc Med. 2007;161:78.

Wells J, Barlow J, Stewart-Brown S. A systematic review of universal approaches to mental health promotion in schools. Health Educ. 2003;103:197–220.

Shackleton N, Jamal F, Viner RM, Dickson K, Patton G, Bonell C. School-based interventions going beyond health education to promote adolescent health: systematic review of reviews. J Adolesc Health. 2016;58:382–96.

Langford R, Bonell CP, Jones HE, Pouliou T, Murphy SM, Waters E, et al. The WHO Health Promoting School framework for improving the health and well-being of students and their academic achievement. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2014. https://doi.org/10.1002/14651858.CD008958.pub2.

Bonell C, Jamal F, Harden A, Wells H, Parry W, Fletcher A, et al. Systematic review of the effects of schools and school environment interventions on health: evidence mapping and synthesis. Public Health Res. 2013;1:1–320.

Domitrovich CE, Bradshaw CP, Poduska JM, Hoagwood K, Buckley JA, Olin S, et al. Maximizing the implementation quality of evidence-based preventive interventions in schools: a conceptual framework. Adv Sch Ment Health Promot. 2008;1:6–28.

Pearson M, Chilton R, Wyatt K, Abraham C, Ford T, Woods H, et al. Implementing health promotion programmes in schools: a realist systematic review of research and experience in the United Kingdom. Implement Sci. 2015;10. https://doi.org/10.1186/s13012-015-0338-6.

Darlington EJ, Violon N, Jourdan D. Implementation of health promotion programmes in schools: an approach to understand the influence of contextual factors on the process? BMC Public Health. 2018;18. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12889-017-5011-3.

Schell SF, Luke DA, Schooley MW, Elliott MB, Herbers SH, Mueller NB, et al. Public health program capacity for sustainability: a new framework. Implement Sci. 2013;8. https://doi.org/10.1186/1748-5908-8-15.

Bumbarger B, Perkins D. After randomised trials: issues related to dissemination of evidence-based interventions. J Childr Serv. 2008;3:55–64.

Scheirer MA, Dearing JW. An agenda for research on the sustainability of public health programs. Am J Public Health. 2011;101:2059–67.

Glasgow RE, Vogt TM, Boles SM. Evaluating the public health impact of health promotion interventions: the RE-AIM framework. Am J Public Health. 1999;89:1322–7.

Fleiszer AR, Semenic SE, Ritchie JA, Richer M-C, Denis J-L. The sustainability of healthcare innovations: a concept analysis. J Adv Nurs. 2015;71:1484–98.

Stirman SW, Kimberly J, Cook N, Calloway A, Castro F, Charns M. The sustainability of new programs and innovations: a review of the empirical literature and recommendations for future research. Implement Sci. 2012;7. https://doi.org/10.1186/1748-5908-7-17.

May C, Finch T. Implementing, embedding, and integrating practices: an outline of normalization process theory. Sociology. 2009;43:535–54.

Feldstein AC, Glasgow RE. A practical, robust implementation and sustainability model (PRISM) for integrating research findings into practice. Jt Comm J Qual Patient Saf. 2008;34:228–43.

Lennox L, Maher L, Reed J. Navigating the sustainability landscape: a systematic review of sustainability approaches in healthcare. Implement Sci. 2018;13. https://doi.org/10.1186/s13012-017-0707-4.

Scheirer MA. Linking sustainability research to intervention types. Am J Public Health. 2013;103:e73–80.

Johnson K, Hays C, Center H, Daley C. Building capacity and sustainable prevention innovations: a sustainability planning model. Eval Program Plann. 2004;27:135–49.

Racine DP. Reliable effectiveness: a theory on sustaining and replicating worthwhile innovations. Adm Policy Ment Health Ment Health Serv Res. 2006;33:356–87.

Simpson DD, Flynn PM. Moving innovations into treatment: a stage-based approach to program change. J Subst Abus Treat. 2007;33:111–20.

Deschesnes M, Couturier Y, Laberge S, Campeau L. How divergent conceptions among health and education stakeholders influence the dissemination of healthy schools in Quebec. Health Promot Int. 2010;25:435–43.

Elias MJ, Zins JE, Graczyk PA, Weissberg RP. Implementation, sustainability, and scaling up of social-emotional and academic innovations in public schools. Sch Psychol Rev. 2003;32:303–19.

Keshavarz N, Nutbeam D, Rowling L, Khavarpour F. Schools as social complex adaptive systems: a new way to understand the challenges of introducing the health promoting schools concept. Soc Sci Med. 2010;70:1467–74.

Tancred T, Paparini S, Melendez-Torres GJ, Fletcher A, Thomas J, Campbell R, et al. Interventions integrating health and academic interventions to prevent substance use and violence: a systematic review and synthesis of process evaluations. Systematic Reviews. 2018;7. https://doi.org/10.1186/s13643-018-0886-3.

Thomas J, Brunton J, Graziosi S. EPPI-reviewer 4.0: software for research synthesis. London: EPPI-Centre Software; 2010.

Hoffmann TC, Glasziou PP, Boutron I, Milne R, Perera R, Moher D, et al. Better reporting of interventions: template for intervention description and replication (TIDieR) checklist and guide. BMJ. 2014;348 mar07 3:g1687.

Shepherd J, Harden A, Rees R, Brunton G, Garcia J, Oliver S, et al. Young people and healthy eating: a systematic review of research on barriers and facilitators. London: EPPI-Centre, Social Science Research Unit, Institute of Education, University of London; 2001.

Gough D. Weight of evidence: a framework for the appraisal of the quality and relevance of evidence. Res Pap Educ. 2007;22:213–28.

Herlitz L, Macintyre H, Bonell C. The barriers and facilitators to sustaining public health interventions in schools in OECD countries. 2017. https://www.crd.york.ac.uk/prospero/display_record.php?ID=CRD42017076320. Accessed 25 Sep 2019.

Thomas J, Harden A. Methods for the thematic synthesis of qualitative research in systematic reviews. BMC Med Res Methodol. 2008;8. https://doi.org/10.1186/1471-2288-8-45.

May C. Towards a general theory of implementation. Implement Sci. 2013;8. https://doi.org/10.1186/1748-5908-8-18.

May CR, Johnson M, Finch T. Implementation, context and complexity. Implement Sci. 2016;11. https://doi.org/10.1186/s13012-016-0506-3.

Tjomsland HE. Health promotion with teachers: evaluation of the Norwegian Network of Health Promoting Schools: quantitative and qualitative analyses of predisposing, reinforcing and enabling conditions related to teacher participation and program sustainability. Bergen: University of Bergen; 2008. http://bora.uib.no/bitstream/handle/1956/3886/Dr.thesis_Hege%20Eikeland%20Tjomsland.pdf?sequence=3&isAllowed=y

Egan CA. Two studies of partnership approaches to comprehensive school physical activity programming: a process evaluation and a case study. South Carolina: University of South Carolina; 2017. http://scholarcommons.sc.edu/etd/4038.

Goh TL. Effects of a movement integration program on elementary school children’s physical activity, fitness levels, and on-task behavior and teachers’ implementation experiences. Doctor of Philosophy. University of Utah; 2014. http://cdmbuntu.lib.utah.edu/utils/getfile/collection/etd3/id/2838/filename/2842.pdf. Accessed 21 Jan 2019.

Tjomsland HE, Bogstad Larsen TM, Viig NG, Wold B. A fourteen year follow-up study of health promoting schools in Norway: principals’ perceptions of conditions influencing sustainability. Open Educ J. 2009;2:54–64.

Goh TL, Hannon JC, Webster CA, Podlog L. Classroom teachers’ experiences implementing a movement integration program: barriers, facilitators, and continuance. Teach Teach Educ. 2017;66:88–95.

Egan CA, Webster CA, Stewart GL, Weaver RG, Russ LB, Brian A, et al. Case study of a health optimizing physical education-based comprehensive school physical activity program. Eval Program Plann. 2019;72:106–17.

Nadeem E, Ringle VA. De-adoption of an evidence-based trauma intervention in schools: a retrospective report from an urban school district. Sch Ment Heal. 2016;8:132–43.

Friend S, Flattum CF, Simpson D, Nederhoff DM, Neumark-Sztainer D. The researchers have left the building: what contributes to sustaining school-based interventions following the conclusion of formal research support? J Sch Health. 2014;84:326–33.

Lytle LA, Ward J, Nader PR, Pedersen S, Williston B. Maintenance of a health promotion program in elementary schools: results from the Catch-on study key informant interviews. Health Educ Behav. 2003;30:503–18.

Kelder SH, Mitchell PD, McKenzie TL, Derby C, Strikmiller PK, Luepker RV, et al. Long-term implementation of the Catch physical education program. Health Educ Behav. 2003;30:463–75.

Schetzina KE, Dalton WT, Lowe EF, Azzazy N, VonWerssowetz KM, Givens C, et al. A coordinated school health approach to obesity prevention among Appalachian youth: the Winning With Wellness Pilot Project. Fam Community Health. 2009;32:271–85.

McKenzie TL, Li D, Derby CA, Webber LS, Luepker RV, Cribb P. Maintenance of effects of the Catch physical education program: results from the Catch-on study. Health Educ Behav. 2003;30:447–62.

Johnson CC, Li D, Galati T, Pedersen S, Smyth M, Parcel GS. Maintenance of the classroom health education curricula: results from the Catch-on study. Health Educ Behav. 2003;30:476–88.

Kalafat J, Ryerson DM. The implementation and institutionalization of a school-based youth suicide prevention program. J Prim Prev. 1999;19:157–75.

Rauscher KJ, Casteel C, Bush D, Myers DJ. Factors affecting high school teacher adoption, sustainability, and fidelity to the “Youth@Work: Talking Safety” curriculum: high school teacher adoption, sustainability and fidelity. Am J Ind Med. 2015;58:1288–99.

Osganian SK, Hoelscher DM, Zive M, Mitchell PD, Snyder P, Webber LS. Maintenance of effects of the eat smart school food service program: results from the Catch-on study. Health Educ Behav. 2003;30:418–33.

Hoelscher D, Feldman HA, Johnson CC, Lytle LA, Osganian SK, Parcel GS, et al. School-based health education programs can be maintained over time: results from the CATCH institutionalization study. Prev Med. 2004;38:594–606.

Elder JP, Campbell NR, Candelaria JI, Talavera GA, Mayer JA, Moreno C, et al. Project salsa: development and institutionalization of a nutritional health promotion project in a Latino community. Am J Health Promot. 1998;12:391–401.

St Pierre T, Kaltreider D. Tales of refusal, adoption, and maintenance: evidence-based substance abuse prevention via school-extension collaborations. Am J Eval. 2004;25:479–91.

Loman SL, Rodriguez BJ, Horner RH. Sustainability of a targeted intervention package: first step to success in Oregon. J Emot Behav Disord. 2010;18:178–91.

Parcel GS, Perry CL, Kelder SH, Elder JP, Mitchell PD, Lytle LA, et al. School climate and the institutionalization of the Catch program. Health Educ Behav. 2003;30:489–502.

Bere E. Free school fruit--sustained effect 1 year later. Health Educ Res. 2006;21:268–75.

Rozema AD, Mathijssen JJP, Jansen MWJ, van Oers JAM. Sustainability of outdoor school ground smoking bans at secondary schools: a mixed-method study. Eur J Pub Health. 2018;28:43–9.

Dijkman MAM, Harting J, van Tol L, van der Wal MF. Sustainability of the good behaviour game in Dutch primary schools. Health Promot Int. 2017;32:79–90.

Crooks CV, Chiodo D, Zwarych S, Hughes R, Wolfe DA. Predicting implementation success of an evidence-based program to promote healthy relationships among students two to eight years after teacher training. Can J Community Ment Health. 2013;32:125–38.

Gorely T, Morris JG, Musson H, Brown S, Nevill A, Nevill ME. Physical activity and body composition outcomes of the GreatFun2Run intervention at 20 month follow-up. Int J Behav Nutr Phys Act. 2011;8:74.

Muckelbauer R, Libuda L, Clausen K, Kersting M. Long-term process evaluation of a school-based programme for overweight prevention. Child Care Health Dev. 2009;35:851–7.

Littlecott HJ, Moore GF, Gallagher HC, Murphy S. From complex interventions to complex systems: using social network analysis to understand school engagement with health and wellbeing. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2019;16:1694.

Murray NG, Low BJ, Hollis C, Cross AW, Davis SM. Coordinated school health programs and academic achievement: a systematic review of the literature. J Sch Health. 2007;77:589–600.

Durlak JA, Weissberg RP, Dymnicki AB, Taylor RD, Schellinger KB. The impact of enhancing students’ social and emotional learning: a meta-analysis of school-based universal interventions: social and emotional learning. Child Dev. 2011;82:405–32.

Farahmand FK, Grant KE, Polo AJ, Duffy SN. School-based mental health and behavioral programs for Low-income, urban youth: a systematic and meta-analytic review: school-based mental health and behavioral programs. Clin Psychol Sci Pract. 2011;18:372–90.

Day C. Chapter 4: sustaining sucess in challenging contexts: leadership in English schools. In: Successful principal leadership in times of change. Dordrecht: Springer; 2007. p. 59–70.

Huberman M. Recipes for busy kitchens: a situational analysis of routine knowledge use in schools. Knowledge. 1983;4:478–510.

Chambers DA, Glasgow RE, Stange KC. The dynamic sustainability framework: addressing the paradox of sustainment amid ongoing change. Implement Sci. 2013;8. https://doi.org/10.1186/1748-5908-8-117.

Gruen RL, Elliott JH, Nolan ML, Lawton PD, Parkhill A, McLaren CJ, et al. Sustainability science: an integrated approach for health-programme planning. Lancet. 2008;372:1579–89.

van Lier PAC, Muthén BO, van der Sar RM, Crijnen AAM. Preventing disruptive behavior in elementary schoolchildren: impact of a universal classroom-based intervention. J Consult Clin Psychol. 2004;72:467–78.

Shediac-Rizkallah MC, Bone LR. Planning for the sustainability of community-based health programs: conceptual frameworks and future directions for research, practice and policy. Health Educ Res. 1998;13:87–108.

Pluye P, Potvin L, Denis J-L. Making public health programs last: conceptualizing sustainability. Eval Program Plann. 2004;27:121–33.

Goodman RM, Steckler AB. A model for the institutionalization of health promotion programs. Fam Community Health. 1989;11:63–78.

McIntosh K, Horner RH, Sugai G. Sustainability of systems-level evidence-based practices in schools: current knowledge and future directions. In: Sailor W, Dunlap G, Sugai G, Horner RH, editors. Handbook of positive behavior support. New York: Springer; 2009. p. 327–52.

Durlak JA, DuPre EP. Implementation matters: a review of research on the influence of implementation on program outcomes and the factors affecting implementation. Am J Community Psychol. 2008;41:327–50.

Aarons GA, Hurlburt M, Horwitz SM. Advancing a conceptual model of evidence-based practice implementation in public service sectors. Adm Policy Ment Health Ment Health Serv Res. 2011;38:4–23.

Rogers EM. Diffusion of innovations. 5th ed. New York: Free Press; 2003.

Leithwood K, Day C. Starting with what we know. In: Day C, Leithwood K, editors. Successful principal leadership in times of change: an international perspective. Dordrecht: Springer Netherlands; 2007. p. 1–13.

Cook CR, Lyon AR, Locke J, Waltz T, Powell BJ. Adapting a compilation of implementation strategies to advance school-based implementation research and practice. Prev Sci. 2019;20:914–35.

Acknowledgements

Not applicable.

Funding

This review was funded through an Economic and Social Research Council PhD scholarship awarded to LH (ref. 1486173).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

LH directed the review; conducted the screening, data extraction and quality appraisal; and carried out the thematic analysis. HM conducted the screening, data extraction and quality appraisal. TO conducted the data extraction and quality appraisal. HM and TO commented on the manuscript. CB contributed to planning the review, advised throughout the review process and contributed to and commented on the manuscript. The manuscript was drafted by LH. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

Not applicable.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary information

Additional file 1:

Search terms for each database.

Additional file 2:

Website search results.

Additional file 3:

Contact with subject experts.

Additional file 4:

Data extraction and quality appraisal form.

Additional file 5:

Quality appraisal guidance and ratings.

Additional file 6:

PRISMA reporting standards.

Additional file 7:

Additional details on sustainability study design participants.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made. The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver (http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/) applies to the data made available in this article, unless otherwise stated.

About this article

Cite this article

Herlitz, L., MacIntyre, H., Osborn, T. et al. The sustainability of public health interventions in schools: a systematic review. Implementation Sci 15, 4 (2020). https://doi.org/10.1186/s13012-019-0961-8

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s13012-019-0961-8