Abstract

Background

To meet emergent healthcare needs, innovations need to be implemented into routine clinical practice. Community pharmacy is increasingly considered a setting through which innovations can be implemented to achieve positive service and clinical outcomes. Small-scale pilot programmes often need scaled up nation-wide to affect population level change. This systematic review aims to identify facilitators and barriers to the national implementation of community pharmacy innovations.

Methods

A systematic review exploring pharmacy staff perspectives of the barriers and facilitators to implementing innovations at a national level was conducted. The databases Medline, EMBASE, PsycINFO, CINAHL, and Open Grey were searched and supplemented with additional search mechanisms such as Zetoc alerts. Eligible studies underwent quality assessment, and a directed content analysis approach to data extraction was conducted and aligned to the Consolidated Framework for Implementation Research (CFIR) to facilitate narrative synthesis.

Results

Thirty-nine studies were included: 16 were qualitative, 21 applied a questionnaire design, and 2 were mixed methods. Overarching thematic areas spanning across the CFIR domains were pharmacy staff engagement (e.g. their positive and negative perceptions), operationalisation of innovations (e.g. insufficient resources and training), and external engagement (e.g. the perceptions of patients and other healthcare professionals, and their relationship with the community pharmacy). Study participants commonly suggested improvements in the training offered, in the engagement strategies adopted, and in the design and quality of innovations.

Conclusions

This study’s focus on national innovations resulted in high-level recommendations to facilitate the development of successful national implementation strategies. These include (1) more robust piloting of innovations, (2) improved engagement strategies to increase awareness and acceptance of innovations, (3) promoting whole-team involvement within pharmacies to overcome time constraints, and (4) sufficient pre-implementation evaluation to gauge acceptance and appropriateness of innovations within real-world settings. The findings highlight the international challenge of balancing the professional, clinical, and commercial obligations within community pharmacy practice. A preliminary theory of how salient factors influence national implementation in the community pharmacy setting has been developed, with further research necessary to understand how the influence of these factors may differ within varying contexts.

Trial registration

A protocol for this systematic review was developed and uploaded onto the PROSPERO international prospective register of systematic reviews database (Registration number: CRD42016038876).

Similar content being viewed by others

Background

A strong primary care system underpins improvements in a nation’s population health [1, 2]; therefore, the primary care sector must continually adapt to meet emergent healthcare needs. Community pharmacies have veered away from traditional dispensing-focused roles as their ability to offer enhanced services within primary care has been recognised [3]. Existing contributions within primary care include the administration of vaccinations [4], smoking cessation support [5], and medication reviews [6, 7]. Additionally, the introduction of pharmacy technicians performing accuracy checks on dispensed medication and the implementation of novel technologies, such as automated dispensing, are considered facilitators to improve efficiency and workflow [8, 9]. This can allow pharmacies more time to offer more patient-focused services.

Access to a healthcare professional without the need for an appointment renders community pharmacies unique to other primary care settings, which enhances the scope of exposure of new services to more patients [10,11,12]. Successful implementation of innovations within healthcare systems underpins the achievement of intended outcomes—for example, improvements in efficiency, safety, or symptomology [13]. For maximal impact within primary care, and to improve population-level health, innovations need scaled up nation-wide [14].

The complexity of national implementation is well acknowledged [15]. Within community pharmacies, service delivery can be dependent on ownership [16], partly due to the autonomous nature of community pharmacies and their requirement to be profitable. Wide-scale implementation is further complicated as barriers and facilitators identified within small-scale, pilot phases may not be generalisable to the national setting [17]. This may be due to the recruitment of “early adopters” who may be less resistant to change [18, 19].

Two previous reviews have explored implementation within the community pharmacy setting. Organisational and individual facilitators to practice change in relation to cognitive pharmacy services have been identified by Roberts et al. [20]. As few empirical studies at this time explored implementation, the results are mostly centred on hypothetical facilitators. More recently, Shoemaker et al. identified barriers and facilitators to the implementation of three services common in the USA (Medication Therapy Management, immunisations, and rapid HIV testing) [21]. However, methodological approaches adopted by these reviews and associated limitations warrant further exploration within this area. The reviews by Shoemaker et al. and Roberts et al. explored barriers and facilitators only for a subset of innovation types. Neither focused specifically on national innovations and included those limited to pilot stages. Additionally, neither critically appraised the included studies, and the reviews included studies which sought perspectives from individuals with no involvement in implementation, meaning the results may not reflect barriers and facilitators truly experienced in practice.

Considering the evolving role of the community pharmacy setting, and the uniqueness of this context, further exploration is required to understand how innovations in this setting can be scaled up to affect nationwide improvements in health. This systemic review addresses this to identify barriers and facilitators to the national implementation of community pharmacy innovations by building upon the reviews previously conducted and overcoming their associated limitations [20, 21]. The objectives of this systematic review are to:

-

1.

Identify studies exploring the factors influencing the national implementation of community pharmacy innovations from the perspectives of community pharmacy staff

-

2.

Synthesise reported barriers and facilitators

-

3.

Develop recommendations for national implementation strategies

Following completion of the systematic review, the opportunity was recognised to develop a preliminary causal theory of how innovations become successfully implemented within community pharmacies at a national level. Therefore, an additional objective was derived:

-

4.

Develop a causal theory of the factors influencing successful national implementation of community pharmacy innovations

Methods

This systematic review is presented according to the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analysis (PRISMA) 2009 checklist [22]. A protocol was developed [23, 24] and uploaded onto the PROSPERO register of systematic reviews (Registration number: CRD42016038876) [25].

Eligibility criteria

Eligible studies sought pharmacy staff’s perspectives on barriers and facilitators to implementing national innovations. An innovation was considered a practice, object, or idea perceived to be new to the setting in which it was implemented [18]. Implementation was considered the process by which an innovation was introduced and applied within the pharmacy setting [26, 27]. Studies solely focusing on views of adoption prior to the implementation of an innovation were outwith the scope of this review as this was considered the preliminary decision-making process of the pharmacy staff to use an innovation [18], which was considered conceptually dissimilar to implementation. Studies involving participants from mixed disciplines (e.g. general practitioners as well as community pharmacy staff) were included if it was possible to extract the data solely pertaining to community pharmacy staff perspectives. Studies from any country were considered eligible for inclusion. Qualitative, quantitative, and mixed method studies were included from peer-reviewed journal articles, conference proceedings, poster presentations, and unpublished literature. The exclusion criteria are presented in Table 1.

Search strategy

The databases Medline, EMBASE, PsycINFO, and the Cumulative Index of Nursing and Allied Health Literature (CINAHL) were searched from their inception on 17 December 2015. Unpublished literature was searched within the Open Grey database [28]. See Additional file 1 for the full Medline search strategy. The search was limited to the English language and covered all studies available up until the search date. Supplementary searches were applied from December 2015 onwards until data analysis concluded in March 2017 (Table 2).

Study selection

Titles and abstracts were screened within Covidence [29], with potentially relevant studies progressing onto full-text screening. The primary reviewer (NW) completed the study selection, with a 20% subset of the title/abstracts and full-texts screened independently. A percentage of agreement was calculated and categorised using the following thresholds: < 70%, poor; 70–79%, fair; 80–89%, good; and > 90%, excellent [30]. A percentage of agreement > 80% was considered adequate [31]. Where the data were published in more than one format, the format which underwent the most extensive peer-review process was included (e.g. a journal article would be selected for data extraction over a conference proceeding).

Data extraction

A data extraction table was devised [24] and piloted in approximately 10% of studies. Piloting identified that delineating the data to barriers and facilitators was oversimplistic as the studies also reported on suggestions of what would have facilitated implementation. These were termed “hypothetical facilitators” and were extracted separately.

Quality assessment

Quality assessment tools were used specific to the method(s) employed. This was to ensure that existing purposefully designed tools were used to assess the quality of either qualitative, quantitative, or mixed method studies to comparable depth. They consisted of a series of questions exploring aspects such as the clarity of the aim, appropriateness of the methodology, recruitment of participants, and data analysis. The 34-item Critical Appraisal Skills Programme (CASP) tool was used to appraise qualitative studies [32]. For questionnaire design studies, the Boynton and Greenhalgh Quality Checklist (BGQC) tool was used [26]. The mixed method studies all applied interviews alongside a questionnaire. Existing mixed method quality assessment tools did not assess questionnaires to the same depth as the BGQC tool [33] and would not offer comparable quality assessment. Therefore, the mixed method studies were assessed using the initial screening questions within the Mixed Methods Appraisal Tool (MMAT) [34], which explores the appropriateness of the mixed method approach, with each method then assessed by the CASP or BGQC tool [26, 32].

The quality assessment tools each have screening questions on the clarity of the aim and appropriateness of the research design. Studies were excluded if these initial criteria were not met. Questionnaire studies which used only closed-ended questions were excluded unless based on previous qualitative work or wider literature as the researchers would have introduced bias based on their a priori assumptions of influential factors [35]. To generate the quality assessment result for each study, each question within the quality assessment tool was attributed a score of 2 if the study fully met the criteria, 1 if partially met, and 0 if not met or unclear. The quality assessment results are presented as percentages as not all questions were applicable to every study [32, 36]. The quality assessment results for the mixed method studies were calculated from the lowest scoring method to ensure the final result did not exceed the quality of the studies weakest component [34]. The quality assessment was conducted by the primary reviewer (NW), with clarification from a mediator when required (ED).

Synthesis of results

The Consolidated Framework for Implementation Research (CFIR) was selected to synthesise the data [37]. The CFIR is a determinant implementation framework of factors influencing implementation amongst five domains: intervention characteristics, the inner setting, the outer setting, characteristics of the individual, and the implementation process [38]. It is widely applied [39], commonly to explore healthcare practitioners’ experiences of implementing an innovation [40], which facilitates cross comparison of results [41]. Each CFIR domain has a number of constructs which are defined in Additional file 2.

A directed content analysis approach [42] was applied where data extraction was conducted inductively, with the synthesis afterwards deductively aligned to the CFIR [43, 44]. This allowed data capture of barriers and facilitators not within the CFIR to test its applicability within the community pharmacy context. As the CFIR constructs are conceptually broad (e.g. one construct is “Knowledge and Beliefs”), data within each CFIR construct was explored for emergent subconstructs [45]. A table quantifying the emergence of barriers, facilitators, and hypothetical facilitators within each CFIR construct was developed, with overarching thematic areas identified from visual analysis [45]. A descriptive narrative synthesis method was chosen to present commonly reported CFIR constructs to facilitate integration of qualitative and quantitative results [46,47,48].

To examine the robustness of the results, a sensitivity analysis involved removal of studies with a quality assessment result of < 50% to observe what effect this had on the reporting frequency of the barriers, facilitators, and hypothetical facilitators [49]. As different studies evaluated the same innovation, the results were categorised both by study and by innovation to see how this affected reporting frequency.

Results

Study selection

Thirty-nine studies were included from the 5874 studies which had titles and abstracts screened (Fig. 1) [6, 50,51,52,53,54,55,56,57,58,59,60,61,62,63,64,65,66,67,68,69,70,71,72,73,74,75,76,77,78,79,80,81,82,83,84,85,86,87]. The percentage of agreement of the titles and abstracts independently screened was 94% (excellent), and for full-texts was 88% (good).

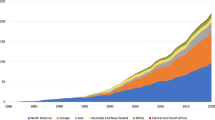

Study characteristics

All studies were published from 2002 onwards, and most since 2010 (n = 28, 72%). Approximately half (n = 20, 51%) originated from the UK. Ten studies originated from other European countries, and the other nine were from Australia (n = 3), Malaysia (n = 2), New Zealand (n = 2), Saudi Arabia (n = 1), and Cambodia (n = 1). The innovation types can be categorised into four subtypes: clinical service (n = 21); pharmacovigilance (n = 6); e-technology (n = 2); and legislative change (n = 10) such as policy changes and reclassification of medicines. Some studies evaluated the same innovation: the UK “Healthy Living Pharmacy” framework (n = 5), the UK “New Medicines Service” (n = 3), the “Danish’ Inhaler Technique Assessment Service” (n = 2), the UK “Medicines Use Review” (n = 3), the Malaysian spontaneous adverse drug reporting system “MADRAC” (n = 2), and the Swedish implementation of ePrescribing (n = 2). Resultantly, the 39 studies report on 28 innovations. Excluding one study which did not provide participant numbers [69], the total number of participants included from the studies is 12,172. Only ten studies (26%) explored perspectives of community pharmacy support staff [52, 54, 57, 61, 63, 69, 70, 75, 82, 83], and two did so exclusively [57, 82]. The full characteristics of included studies are within Additional file 3.

Quality assessment results

An overview of the quality assessment results is within Table 3, with the full quality assessment in Additional file 4. Five studies were excluded as they applied questionnaires with only closed-ended questions which were not reported to be developed from reference to literature or previous qualitative findings [88,89,90,91,92].

Qualitative studies

All qualitative studies (n = 16) detailed the research aims and rationalised the study’s importance and relevance. Six justified why a qualitative design was chosen [54, 55, 60, 70, 77, 83], and three justified the specific method adopted [61, 69, 77]. For one study which employed two qualitative methods, only one method was explicitly justified [74]. Six studies made the methods fully explicit by including the interview or focus group guide [52, 55, 57, 61, 74, 77]. No studies offered a full account of reflexivity as none adequately considered the researcher-participant relationship, although some reflected on potential bias during data collection and sampling [57, 62, 77, 82]. No study sufficiently discussed the credibility of their findings as per the quality assessment criteria.

Questionnaire design studies

All questionnaire design studies (n = 21) had a clear research question. Six studies did not attain a response rate of > 50% [59, 65, 76, 78, 79, 86], and three employed sampling methods which made it not possible to determine response rates [50, 63, 80]. Two studies sampled a single pharmacy chain [72, 73], and six sampled participants within specific geographical locations [51, 58, 59, 63, 68, 81]. Twelve studies piloted the questionnaire in a representative cohort [6, 51, 58, 59, 64,65,66,67, 78,79,80, 86]. Four studies did not offer sufficient detail to determine if the pilot sample was representative of study participants [50, 63, 68, 85], and for one study, the pilot sample was not representative [72]. One study modified an existing questionnaire without re-piloting it [73], and three studies did not state if the questionnaire was piloted [71, 76, 81]. Three studies had claims for both validity and reliability [51, 59, 80], ten had claims for neither [6, 50, 58, 63, 65, 67, 68, 71, 73, 85], and the remaining eight conducted face and/or content validity testing [64, 66, 72, 76, 78, 79, 81, 86].

Mixed method studies

The mixed method studies were low in quality due to insufficient details as both were conference proceedings [53, 84]. One study did not explain the rationale for integrating qualitative and quantitative methods [53], and neither described how the data was integrated [53, 84].

Barriers, facilitators, and hypothetical facilitators

The reporting frequency of the barriers, facilitators, and hypothetical facilitators aligned to the CFIR constructs is shown in Table 4. A full presentation of constructs and subconstructs is in Additional file 5. When removing studies with a quality assessment score of < 50% (n = 12, 41%), no changes were identified to the most commonly reported CFIR constructs amongst the barriers, facilitators, and hypothetical facilitators. Likewise, when categorising results by innovation and not by study, the most commonly reported CFIR constructs remained the same. Therefore, for completeness, all studies were retained within the analysis.

Thirteen (33%) CFIR constructs were cited by at least ten studies (25%) as a barrier, facilitator, or hypothetical facilitator. Overarching thematic areas spanning across the CFIR domains were identified: pharmacy staff engagement, operationalisation of the innovation, and external engagement (Table 5).

Pharmacy staff engagement

Knowledge and beliefs about the intervention

Positive and negative views of the innovation by the pharmacy staff were commonly cited factors influencing implementation. Nine studies had mixed views from participants [52, 55, 57, 62, 72, 73, 78, 85, 86]. The negative perceptions were varied and in many instances context specific, but included concerns and a lack of belief in/support for the innovation [51, 52, 55, 57,58,59,60, 62, 66, 69, 72,73,74, 78, 80, 85,86,87]. Positive perceptions included a belief in/support for the innovation [6, 50,51,52, 55,56,57,58,59,60,61,62, 67, 68, 72, 73, 75, 78, 85, 86] and positivity about the way the innovation was implemented [84].

In four studies, good awareness and understanding surrounding the innovation were cited [52, 62, 68, 85]. Notably for two of these, lack of knowledge was also cited by some participants [62, 85]. Lack of awareness [51, 59, 60, 68, 84] and operational knowledge [51, 57,58,59,60, 62, 68, 76, 84, 85] was common, and lack of appropriate clinical knowledge was cited by five studies [51, 58, 59, 70, 85]. All pharmacovigilance studies cited a lack of awareness and knowledge [51, 58,59,60, 68, 85].

Compatibility—with roles/values

An innovation’s compatibility with the roles and values of a pharmacist was reported. This included alignment with ambitions [78], the innovation recognising the potential of the pharmacy profession to adopt enhanced or professional roles [61, 74], or being considered integral to a pharmacist’s role [51, 56, 59, 60, 68, 85, 87].

Relative advantage

An innovation offering an advantage was evident within 12 studies [50, 54, 61, 64, 75, 77, 79,80,81, 83, 85, 87]. General advantages included enhanced engagement or relationship with patients [50, 61, 79, 87]; improvement in workforce capability, such as improved education, awareness, or confidence [54, 61, 75, 85]; better relationship with surrounding healthcare professionals [79, 83]; and the innovation benefitting patients [64, 75, 77, 79, 80, 83]. Some were context specific, for example, the time-saving aspect of the Swedish ePrescribing system [64, 81], and the Scottish Minor Ailments Service [79] meaning product cost is no longer considered during consultations [79]. Six studies reported that the innovation presented disadvantages [55, 62,63,64, 79, 81], and three cited both advantages and disadvantages of an innovation [64, 79, 81].

External policy and incentives

This construct relates to policy and incentives originating from government or other central entities [93]. In relation to external policy, reported barriers included the innovation not being aligned with policy [65]. Studies suggested hypothetical facilitators including extending the scope of innovations [6, 52, 65] and making participation in pharmacovigilance innovations compulsory [51, 58, 60, 85]. In relation to external incentives, lack of/insufficient funding [6, 83] or remunerations [50, 76, 79] were reported barriers. Suggestions of incentives which could facilitate implementation were primarily financial [50,51,52, 60, 65, 72, 76, 85], but also included the provision of awards, certifications, journal subscription, and conference attendance [60] or penalising other healthcare professionals for lack of co-operation [50].

Organisational incentives and rewards

This CFIR construct relates to incentives and rewards originating from specific pharmacy organisations, as well personal incentives of the community pharmacy staff [93]. One study cited negative perceptions of target setting within the pharmacy, which were perceived as income-focused rather than patient-focused [87]. For clinical services and legislative changes, personal rewards included improved professional recognition [50, 56, 61, 79], enhanced influence or role [50, 72, 77,78,79, 86], and personal or professional satisfaction [52, 56, 74, 76, 82]. Commercial benefits spanned across all innovations, including financial betterment for the pharmacy [57, 61, 64, 78, 79] and increased customer footfall [52, 83].

Engaging innovation participants

There was little data pertaining to how the implementation strategy influenced implementation. Better informing and engaging the pharmacy workforce was a suggested hypothetical facilitator [51, 54, 55, 59, 60, 68, 71, 74, 85], including better collaboration between pharmacies [54], educational campaigns [71], mentoring and networking opportunities [55, 74], culture change [68], better advertising [51, 85], and promotion [59, 60, 85].

Operationalisation of the innovation

Available resources

Lack of time [6, 50,51,52,53,54, 57,58,59,60,61, 65, 68, 70,71,72,73, 75, 76, 79, 81, 83, 85, 87] and increased workload [50, 54, 61, 83, 84] associated with an innovation were common. Issues included insufficient staffing [72, 73, 76, 78] and losing staff to training events [61], and one study reported the benefits of having two pharmacists on duty [74]. Two studies reported a general lack of operational resources [70, 79]. Studies mostly reported innovation-specific barriers such as a lack of printers [65] and reporting forms for adverse drug reporting [51, 58,59,60, 85]. Lack of access to clinical information was cited for both the legislative and clinical services [66, 67, 72, 78, 79] as was a lack of suitable space [57, 72, 76, 78]. Two studies cited adequate pharmacy facilities, such as a consultation room [71, 73]. Six studies reported valued resources associated with an innovation [57, 61, 62, 64, 71, 74], and nine suggested resources which would facilitate implementation [6, 51, 55, 65, 72, 79, 81, 84, 87], including access to clinical information about patients [79, 87], reporting forms [50], improved IT systems [6, 55, 65, 79, 81], a consultation area [71], and a “fact sheet” to facilitate implementation [84].

Design quality and packaging

Poor design was most common amongst clinical services. This included the requirement of patient consent devaluing the innovation and patient’s perception of the pharmacist as a professional [56], being unaware of a patient’s discharge from hospital [67], lapsing of customer registration [79], and inappropriate patient referrals [55]. For a service where medication information was legislated to be supplied to all patients, information was not available in other languages and considered too long to print [65]. For a pharmacovigilance program, centralisation of the reporting system was a barrier [59]. Poor quality of the innovation mainly pertained to IT or system issues [58, 61, 74, 78, 81] or the nature of the paperwork involved [58, 67]. Eleven studies suggested improvements to the design and quality of the innovations [51, 55, 58,59,60, 64, 65, 67, 72, 85, 86].

Complexity

Difficultly of an innovation [50, 56, 57, 63, 74, 78] and the complexity of its operationalisation were reported [60, 78], with the latter most commonly relating to the complexity of the remuneration or reporting processes [6, 51, 56, 59, 74, 85]. One study reported barriers relating to the complexity of the implementation process itself [84]. Three studies suggested simplifying reporting procedures [51, 59, 85].

Compatibility—with systems

Incompatibility with work systems [65] or applicability in certain settings [57] was reported. Three studies cited compatibility with working systems as a facilitator [57, 71, 74], and work process change was suggested in one study to facilitate [65].

Access to knowledge and information

Two studies cited training received to be useful [57, 86]; however, a lack of appropriate training was cited by other participants for one of these studies [57]. Inadequacy of the training was cited by five studies, including the training not meeting the needs of staff [86], the lack of appropriate training [55, 57, 71], or the training focusing on filling out forms rather than skills-based [87]. Whilst three studies cited a lack of information available on the innovation [57, 74, 79], four had participants comment positively on information received [57, 62, 71, 78]. Better access to information and training was a suggested hypothetical facilitator reported by 17 studies [50, 51, 55, 57,58,59,60, 62, 65, 68, 71, 74, 76, 77, 80, 84, 85], including suggestions of continuous training [50, 51, 59, 60, 62], mentoring and peer review [74], and incorporating training within undergraduate pharmacy degrees [58, 60, 85].

External engagement

Cosmopolitanism

Pharmacy staff perceived that other healthcare professionals held negative views for the legislative and clinical services. Seven studies cited negative response [6, 50, 52, 72, 74, 77, 79], which included reluctance [50], lack of support [78], or general negative views [6, 52, 72, 74, 77]. Lack of referral was a cited barrier for clinical services [54, 55, 67, 77], and lack of collaboration and communication with healthcare professionals was also apparent [60, 71, 74, 77,78,79, 87]. Facilitators included doctor referrals [61], establishment of new contacts [54], and having pre-existing relationships with other healthcare professionals [77].

Patient needs and resources

Although there were no reports from studies evaluating pharmacovigilance innovations within this construct, other innovation types had numerous citations. Patient’s support and acceptance of the innovation [75, 77, 80, 83] and positive feedback [54, 57, 82, 83] were contrasted by negative perceptions [50, 52, 63, 75, 77, 78]. These included resistance to change or advice [50, 63, 75, 78], perceiving the innovation as lacking in value [77], and perceiving “pharmacists as drug suppliers only” [52]. Two studies reported patient demand [55, 57]; however, pharmacy staff generally reported low public demand [57, 62, 74, 77,78,79, 86] or that patients were uninterested or reluctant [6, 65, 72, 77]. For the clinical services, there was difficulty recruiting patients [56], reaching targets [61, 77], and retaining patients [56], or patients could not attend appointments [53, 74, 77]. One study reported public awareness [57], yet lack of public knowledge or awareness was more commonly reported [54, 57, 61, 63, 64, 74, 77, 82].

Engaging stakeholders

Although three studies cited lack of advertising or promotion of the innovation as a barrier to patient engagement [59, 74, 79], 12 studies across all innovation types suggested better informing and engaging patients [6, 50, 52, 54, 57, 61, 64, 65, 68, 76, 80, 85]. One study reported that banners and displays increased customer awareness [83]. Suggested facilitators included patient education programmes [64, 65, 79, 80] and local publicity and media campaigns [52, 54, 57, 61]. Five studies suggested better engagement with other healthcare professionals [50, 64, 68, 74, 77].

Discussion

This systematic review evaluated heterogeneous innovations to identify the factors influencing national implementation within the community pharmacy setting. Three key thematic areas were identified: (1) pharmacy staff engagement with implemented innovations, including staff perceptions and beliefs regarding the innovation; (2) operationalisation of the innovation, such as lack of resources; and (3) external engagement with implemented innovations, including perceived negative views of patients and other healthcare professionals. We discuss each in turn with cross comparison to previous reviews conducted by Roberts et al. [20] and Shoemaker et al. [21]. A comparison of the emergent CFIR constructs with these reviews is available in Additional file 6.

In relation to pharmacy staff engagement, mixed positive and negative perceptions of innovations by pharmacy staff were apparent. This is in contrast to previous reviews which found that pharmacists are generally favourable towards new services [94] and that pharmacists’ positive beliefs and attitudes about a service facilitate successful implementation [20, 21]. This review’s findings may reflect the inclusion of national innovations only, as barriers emerging in small-scale pilot phases may not reflect the barriers experienced following scale up [17].

Innovations were considered advantageous by pharmacy staff if they enhanced the relationship with patients, improved relationships with surrounding healthcare professionals, benefitted patients, or improved workforce capability. Personal incentives included professional satisfaction, recognition, and influence. Shoemaker et al.’s review also identified that improving patients’ health and relationship with the pharmacy was advantageous [21] and that demonstration of skillset and perceived value to the public was an incentive [21]. Shoemaker at al additionally found the acquisition of new patients attending the pharmacy to be a facilitator of implementation [21], and the positive influence of monetary incentives and financial betterment mirrors previous findings [20, 21]. These findings highlight the challenge of balancing the professional, clinical, and commercial obligations within the community pharmacy setting [95]. Although exploring pre-implementation phases was outwith the scope of this review, exploring the cognitive processes underpinning decisions to implement innovations in light of financial and personal incentives, and how these weigh against patient-related benefits, would be an interesting area for future research [96].

The most commonly reported barrier in relation to the operationalisation of an innovation was the lack of available resources (e.g. time and workload constraints) which echoed Shoemaker et al.’s findings [21]. Beyond staff recruitment, the promotion of whole-team engagement and delegation of tasks to pharmacy support staff may facilitate more efficient workflow [97,98,99,100,101] and practice change [20]. Barriers relating to insufficient resources and training were common, as was poor design, complexity, and incompatibly of the innovation, with the latter two also identified by Shoemaker et al. [21]. “Bottom-up” implementation strategies with front-line staff involved in the design and testing of innovations may overcome resource insufficiencies and design flaws [102, 103].

External engagement centred on the perceptions of other healthcare professionals and patients. Negative perceptions of other healthcare professionals, and lack of communication and collaboration with pharmacy staff, was a barrier. Roberts et al. also identified that communication with doctors and their attitudes influenced successful implementation of cognitive pharmacy services [20], whilst Shoemaker et al. identified cosmopolitanism and engagement of the wider healthcare setting to be a facilitator [21]. General practitioners have previously reported lack of collaboration with community pharmacies [104], with evidence that they are cautious about their adoption of new services [105] and clinical roles [106,107,108,109].

The influence of perceived patient acceptance was also prominent—community pharmacy staff cited lack of patient demand and their resistance towards innovations. Conversely, a review of patient-reported satisfaction with community pharmacy services found high satisfaction [110], and a disparity between how pharmacists perceive patient satisfaction and how patients report satisfaction has been previously identified [111]. Shoemaker et al. identified patient demand for vaccination services and acceptance of Medication Therapy Management, with no barriers identified relating to patient engagement [21]. Additionally, low public awareness of innovations was commonly cited, and there have been mixed findings in relation to patient awareness of community pharmacies’ roles [111,112,113,114,115]. Informing the public was a commonly reported hypothetical facilitator, suggesting that poor public engagement is perceived as a limitation of the implementation strategies adopted.

Development of a preliminary theory and recommendations for future research

A critical output of this systematic review was the identification of the three overarching thematic areas (Table 5). The identification of these overarching thematic areas allowed for a preliminary causal theory to be developed (Fig. 2). This was not an initial objective of this review as per the initial PROSPERO record (Registration number: CRD42016038876). This preliminary theory proposes that successful national implementation of an innovation requires (1) the pharmacy staff to positively engage with an innovation, (2) the innovation to be easily operational within community pharmacies, and (3) the positive external engagement of patients and other healthcare professionals. The authors view a community pharmacy-specific theory to be necessary due to its distinctiveness when compared to other primary care settings—for example, patients are able to consult with a healthcare professional within community pharmacies without the need for an appointment. Furthermore, the theory presents the high-level influencers of successful implementation within this setting, which may facilitate evaluations if exploration of all 39 CFIR constructs is not feasible.

Further work is needed to understand the interaction between the three overarching thematic areas and to consider how the influence of each may differ within varying contexts and settings. Once tested further, applying this theory at an early stage of an innovation’s implementation process could inform potential refinements to an innovation. As “External Engagement” was an emergent theme, this exemplifies the impact of the surrounding outer context and indicates that the community pharmacy setting is not detached from the wider primary care setting. Wider exploration of the perspectives of other healthcare professionals and the public may strengthen this understanding.

In line with previous work, this review identified that adopted implementation strategies are poorly reported in the literature [14, 21], and the development of innovations was also poorly described. Future studies should explicitly report the implementation strategies being adopted and greater details of the innovation being implemented, including its development, to allow for consideration of how these aspects may influence successful implementation [116, 117].

The emergent CFIR constructs identified in this review complemented those from related reviews [20, 21], which suggests our findings are valid. However, given the methodological differences in the review approaches, this should be interpreted with a degree of caution. Two CFIR constructs cited by Shoemaker et al. and Roberts et al. were not emergent in this review: “Culture” [20, 21] and “Trialability” [21]. As Roberts et al. only reported “culture in pharmacy” and did not elaborate, it was not possible to consider why culture was reported in this previous review and not in the current review. Shoemaker et al. coded “alignment with missions/priorities” and “commitment to providing preventive services” within “Culture”, which the current authors would have coded within “Compatibility” (i.e. how the innovation “aligns with individuals’ own norms and values”) [37]. With regards to “Trialability”, Shoemaker et al. identified that slow expansion of immunisation services facilitated implementation, which would unlikely be salient within scaled-up national services [21]. It was more common for differences to emerge in the valence of the reported CFIR constructs. For example, the current review identified negative patient perceptions (patient needs and resources) and lack of engagement of external healthcare professional (cosmopolitanism), whereas Shoemaker et al. only reported facilitators within these CFIR constructs [21]. This may suggest that emergence of barriers and facilitators at national level is comparable to those in small-scale pilot stages, yet the strength of influence they have on implementation may differ, which would be an interesting area for further research.

Recommendations for future implementation strategies

From these findings, future implementation strategies (Table 6) for national community pharmacy innovations should involve the use of piloting strategies, promotion of whole-team involvement, pre-implementation exploration, and stakeholder engagement strategies.

Strengths and limitations

Alignment of the results to the CFIR positions the research within the wider implementation science literature. However, the inclusion of qualitative and quantitative studies and the varying level of reporting detail meant it was not possible to weight identified barriers and facilitators and deduce relative influences. The results instead reflected the number of reporting studies, which is not uncommon for reviews of this nature [20, 21, 118,119,120]. Primary studies would benefit from applying the CFIR “rating rules” which explore the valence (i.e. positive or negative impact) and strength of influence of emergent CFIR constructs [93]. Nevertheless, tabulation of the results facilitated consideration of the relationship between constructs and cross comparison [45].

The inclusion of qualitative, quantitative, and mixed method studies ensured wide exploration of the barriers and facilitators in this context, which meant that different quality assessment tools were applied. Although tools of similar depth were selected, it is notable that the CASP and BGQC tools covered different aspects of quality [26, 32]. For example, the BGQC tool does not explore the relationship between participants and researchers unlike the CASP tool. Therefore, to what extent the quality assessment results are truly comparable between study types is unknown.

To the authors’ knowledge, using a directed content analysis approach when applying the CFIR is novel and helped assess its applicability to the community pharmacy setting. The CFIR constructs captured most emergent data except for two instances within the CFIR outer setting domain. Patients’ perceptions, awareness, and engagement were not encompassed within the “Patient Needs and Resources” construct as the construct focuses on the ability of an organisation to identify and prioritise patient’s needs (which has been criticised elsewhere [121]). The “Cosmopolitanism” construct overlooks the impact of external healthcare professional’s engagement as it centres on networking with external organisations, and further exploration of how cosmopolitanism may be influenced by the infrastructure of healthcare systems is required. Both of these factors would not appear relevant in any other CFIR domain or construct, and we suggest widening the scope of these CFIR constructs accordingly.

Limiting the search to the English language compromised the ability to identify implementation facilitators and barriers internationally. However, 41% (n = 16) of included studies were from non-English-speaking nations. During full-text screening, 35 studies could not be accessed. As only 8% (n = 29) of the 358 studies screened were included, we estimate only three of these would be eligible for inclusion. Although the study selection process underwent independent validation, alignment of the results to the CFIR was not conducted independently. However, a dedicated CFIR codebook and technical assistance guide was routinely accessed to ensure appropriate alignment to CFIR constructs [93]. Lower quality studies were retained to allow for broad data capture, and removal of the lower quality studies did not affect the representation of the most commonly cited CFIR constructs. Conference abstracts obtained the lowest quality scores—likely to be reflective of their reporting depth—although retaining these ensured representation of the latest research [120].

Conclusions

Pharmacy staff’s perceptions of the barriers and facilitators to the implementation of national innovations within the community pharmacy setting have been identified. Commonly reported factors which influence implementation include insufficient resources, the views of patients and other healthcare professionals, pharmacy staff perceptions and acceptance of innovations, and belief that innovations were beneficial. Key findings led to the development of a preliminary theory where it is proposed that successful national implementation of community pharmacy innovations requires innovations which are easy to operate, alongside positively engaged patients, pharmacy staff, and other healthcare professionals such as GPs. Potential applications of the results include better directed evaluations and the development of implementation strategies which overcome common barriers and exploit known facilitators. Key recommendations include (1) more robust piloting and sufficient pre-implementation exploration, (2) phased implementation, (3) promotion of whole-team involvement, and (4) more thorough engagement strategies.

Abbreviations

- BGQC:

-

Boynton and Greenhalgh Quality Checklist

- CASP:

-

Critical Appraisal Skills Programme

- CFIR:

-

Consolidated Framework for Implementation Research

- CINAHL:

-

Cumulative Index of Nursing and Allied Health Literature

- MADRAC:

-

Malaysian spontaneous adverse drug reporting system

- MMAT:

-

Mixed Methods Appraisal Tool

- PRISMA:

-

Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analysis

References

Macinko J, Starfield B, Shi L. The contribution of primary care systems to health outcomes within Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development (OECD) countries, 1970–1998. Health Serv Res. 2003;38:831–65.

World Health Organization. The world health report 2008: primary health care now more than ever. Geneva 2008 [cited 2018 Jun 12]. Available from: http://apps.who.int/medicinedocs/en/m/abstract/Js22232en/.

Wiedenmayer K, Summers R, Mackie C, Gous AGS, Everard M. Developing pharmacy practice: a focus on patient care: Geneval World Health Organization and International Pharmaceutical Federation; 2006.

Francis M, Hinchliffe A. Vaccination services through community pharmacy: a literature review: public health Wales; 2010 [cited 2018 Jun 12]. Available from: http://www.wales.nhs.uk/sitesplus/888/news/17071.

Brown TJ, Todd A, Malley C, Moore HJ, Husband AK, Bambra C, et al. Community pharmacy-delivered interventions for public health priorities: a systematic review of interventions for alcohol reduction, smoking cessation and weight management, including meta-analysis for smoking cessation. BMJ Open. 2016;6. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmjopen-2015-009828.

Lee E, Braund R, Tordoff J. Examining the first year of medicines use review services provided by pharmacists in New Zealand: 2008. N Z Med J. 2009;122:3566.

Hatah E, Braund R, Tordoff J, Duffull SB. A systematic review and meta-analysis of pharmacist-led fee-for-services medication review. Br J Clin Pharmacol. 2014;77:102–15. https://doi.org/10.1111/bcp.12140.

Frost TP, Adams AJ. Tech-check-tech in community pharmacy practice settings. J Pharm Technol. 2016;33:47–52. https://doi.org/10.1177/8755122516683519.

Spinks J, Jackson J, Kirkpatrick CM, Wheeler AJ. Disruptive innovation in community pharmacy–impact of automation on the pharmacist workforce. Res Social Adm Pharm. 2017;13:394–7. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.sapharm.2016.04.009.

World Health Organization. The role of the pharmacist in the health care system. New Delhi 1994 [cited 2018 Jun 12]. Available from: http://apps.who.int/medicinedocs/en/d/Jh2995e/.

Todd A, Copeland A, Husband A, Kasim A, Bambra C. Access all areas? An area-level analysis of accessibility to general practice and community pharmacy services in England by urbanity and social deprivation. BMJ Open. 2015;5:e007328. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmjopen-2014-007328.

Todd A, Copeland A, Husband A, Kasim A, Bambra C. The positive pharmacy care law: an area-level analysis of the relationship between community pharmacy distribution, urbanity and social deprivation in England. BMJ Open. 2014;4:e005764. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmjopen-2014-005764.

Proctor E, Silmere H, Raghavan R, Hovmand P, Aarons G, Bunger A, et al. Outcomes for implementation research: conceptual distinctions, measurement challenges, and research agenda. Admin Pol Ment Health. 2011;38:65–76. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10488-010-0319-7.

Ben Charif A, Zomahoun HTV, LeBlanc A, Langlois L, Wolfenden L, Yoong SL, et al. Effective strategies for scaling up evidence-based practices in primary care: a systematic review. Implement Sci. 2017;12:139. https://doi.org/10.1186/s13012-017-0672-y.

Raine R, Fitzpatrick R, Barratt H, Bevan G, Black N, Boaden R, et al. Challenges, solutions and future directions in the evaluation of service innovations in health care and public health. Health services and delivery research. Southampton: NIHR Journals Library; 2016.

Bush J, Langley CA, Wilson KA. The corporatization of community pharmacy: implications for service provision, the public health function, and pharmacy's claims to professional status in the United Kingdom. Res Social Adm Pharm. 2009;5:305–18. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.sapharm.2009.01.003.

Barker PM, Reid A, Schall MW. A framework for scaling up health interventions: lessons from large-scale improvement initiatives in Africa. Implement Sci. 2016;11:1–11. https://doi.org/10.1186/s13012-016-0374-x.

Rogers EM. Diffusion of innovations. 5th ed. New York: Free Press; 2003.

Tann J, Blenkinsopp A, Allen J, Platts A. Leading edge practitioners in community pharmacy: approaches to innovation. Int J Pharm Pract. 1996;4:235–45. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.2042-7174.1996.tb00874.x.

Roberts AS, Benrimoj SI, Chen TF, Williams KA, Aslani P. Implementing cognitive services in community pharmacy: a review of facilitators used in practice change. Int J Pharm Pract. 2006;14:163–70. https://doi.org/10.1211/ijpp.14.3.0002.

Shoemaker SJ, Curran GM, Swan H, Teeter BS, Thomas J. Application of the consolidated framework for implementation research to community pharmacy: a framework for implementation research on pharmacy services. Res Social Adm Pharm. 2017;13:905–13. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.sapharm.2017.06.001.

Moher D, Liberati A, Tetzlaff J, Altman DG, The PG. Preferred reporting items for systematic reviews and meta-analyses: the PRISMA statement. PLoS Med. 2009;6:e1000097. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pmed.1000097.

Moher D, Shamseer L, Clarke M, Ghersi D, Liberati A, Petticrew M, et al. Preferred reporting items for systematic review and meta-analysis protocols (PRISMA-P) 2015 statement. Systematic Reviews. 2015;4:1. https://doi.org/10.1186/2046-4053-4-1.

Noyes J, Booth A, Hannes K, Harden A, Harris J, Lewin S, et al. Supplementary guidance for inclusion of qualitative research in cochrane systematic reviews of interventions. Cochrane Collaboration Qualitative Methods Group, 2011. Version 1 (updated August 2011). [cited 2016 Feb 2]. Available from: http://cqrmg.cochrane.org/supplemental-handbook-guidance.

PROSPERO: International prospective register of systematic reviews. : National Institute for Health Research; 2016 [cited 2018 Jun 11]. Available from: https://www.crd.york.ac.uk/PROSPERO/.

Greenhalgh T, Robert G, Bate P, Macfarlane F, Kyriakidou O, Donaldson L. Diffusion of innovations in health service organisations: a systematic literature review. London: Wiley; 2007.

Rabin BA, Purcell P, Naveed S, Moser RP, Henton MD, Proctor EK, et al. Advancing the application, quality and harmonization of implementation science measures. Implement Sci. 2012;7. https://doi.org/10.1186/1748-5908-7-119.

Open Grey. System for Information on Grey Literature [cited 2018 Feb]. Available from: http://www.opengrey.eu.

Covidence. Better systematic review management [cited 2018 Oct] Available from: https://www.covidence.org/home.

Cicchetti DV. The precision of reliability and validity estimates re-visited: distinguishing between clinical and statistical significance of sample size requirements. J Clin Exp Neuropsychol. 2001;23:695–700. https://doi.org/10.1076/jcen.23.5.695.1249.

House AE, House BJ, Campbell MB. Measures of interobserver agreement: calculation formulas and distribution effects. J Behav Assess. 1981;3:37–57. https://doi.org/10.1007/BF01321350.

Critical Appraisal Skills Programme. CASP Qualitative Checklist 2018 [cited 2018 Feb]. Available from: http://www.casp-uk.net/.

Heyvaert M, Hannes K, Maes B, Onghena P. Critical appraisal of mixed methods studies. J Mix Methods Res. 2013;7:302–27. https://doi.org/10.1177/1558689813479449.

Pluye P, Robert E, Cargo M, Bartlett G, O’Cathain A, Griffiths F, et al. Proposal: a mixed methods appraisal tool for systematic mixed studies reviews. 2011 [cited 2018 12th of June]. Available from: http://mixedmethodsappraisaltoolpublic.pbworks.com.

Mills EJ, Nachega JB, Bangsberg DR, Singh S, Rachlis B, Wu P, et al. Adherence to HAART: a systematic review of developed and developing nation patient-reported barriers and facilitators. PLoS Med. 2006;3:e438. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pmed.0030438.

Masood M, Thaliath ET, Bower EJ, Newton JT. An appraisal of the quality of published qualitative dental research. Community Dent Oral Epidemiol. 2011;39:193–203. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1600-0528.2010.00584.x.

Damschroder LJ, Aron DC, Keith RE, Kirsh SR, Alexander JA, Lowery JC. Fostering implementation of health services research findings into practice: a consolidated framework for advancing implementation science. Implement Sci. 2009;4:1–15. https://doi.org/10.1186/1748-5908-4-50.

Nilsen P. Making sense of implementation theories, models and frameworks. Implement Sci. 2015;10:53. https://doi.org/10.1186/s13012-015-0242-0.

Birken SA, Powell BJ, Shea CM, Haines ER, Alexis Kirk M, Leeman J, et al. Criteria for selecting implementation science theories and frameworks: results from an international survey. Implement Sci. 2017;12:124. https://doi.org/10.1186/s13012-017-0656-y.

Kirk MA, Kelley C, Yankey N, Birken SA, Abadie B, Damschroder L. A systematic review of the use of the Consolidated Framework for Implementation Research. Implement Sci. 2015;11:72. https://doi.org/10.1186/s13012-016-0437-z.

Kirk MA, Kelley C, Yankey N, Birken SA, Abadie B, Damschroder L. A systematic review of the use of the consolidated framework for implementation research. Implement Sci. 2016;11:72. https://doi.org/10.1186/s13012-016-0437-z.

Hsieh HF, Shannon SE. Three approaches to qualitative content analysis. Qual Health Res. 2005;15:1277–88. https://doi.org/10.1177/1049732305276687.

Elo S, Kyngas H. The qualitative content analysis process. J Adv Nurs. 2008;62:107–15. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1365-2648.2007.04569.x.

Green SA, Bell D, Mays N. Identification of factors that support successful implementation of care bundles in the acute medical setting: a qualitative study. BMC Health Serv Res. 2017;17:120. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12913-017-2070-1.

Keith RE, Crosson JC, O'Malley AS, Cromp D, Taylor EF. Using the Consolidated Framework for Implementation Research (CFIR) to produce actionable findings: a rapid-cycle evaluation approach to improving implementation. Implement Sci. 2017;12:15. https://doi.org/10.1186/s13012-017-0550-7.

Noyes J, Lewin S. Chapter 6: supplemental guidance on selecting a method of qualitative evidence synthesis, and integrating qualitative evidence with cochrane intervention reviews. In: Noyes J, Booth A, Hannes K, Harden A, Harris J, Lewin S, et al., editors. Supplementary guidance for inclusion of qualitative research in cochrane systematic reviews of interventions version 1 (updated August 2011) Cochrane Collaboration Qualitative Methods Group; 2011.

Popay J, Roberts H, Sowden A, Petticrew M, Arai L, Rodgers M, et al. Guidance on the conduct of narrative synthesis in systematic reviews. A product from the ESRC methods programme; 2006 [cited 2018 Oct] Available from: https://www.lancaster.ac.uk/shm/research/nssr/research/dissemination/publications.php.

Dixon-Woods M, Agarwal S, Jones D, Young B, Sutton A. Synthesising qualitative and quantitative evidence: a review of possible methods. J Health Serv Res Policy. 2005;10:45–53. https://doi.org/10.1177/135581960501000110.

Carroll C, Booth A, Lloyd-Jones M. Should we exclude inadequately reported studies from qualitative systematic reviews? An evaluation of sensitivity analyses in two case study reviews. Qual Health Res. 2012;22:1425–34. https://doi.org/10.1177/1049732312452937.

Allenet B, Barry H. Opinion and behaviour of pharmacists towards the substitution of branded drugs by generic drugs: survey of 1,000 French community pharmacists. Pharm World Sci. 2003;25:197–202.

Bawazir S. Attitude of community pharmacists in saudi arabia towards adverse drug reaction reporting. Saudi Pharm J. 2006;14:75–83. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jsps.2018.11.002.

Bell CA, Eang MT, Dareth M, Rothmony E, Duncan GJ, Saini B. Provider perceptions of pharmacy-initiated tuberculosis referral services in Cambodia, 2005-2010. Int J Tuberc Lung Dis. 2012;16:1086–91.

Blenkinsopp A, Celino G, Bond C, Inch J, Gray N. Community pharmacists’ experience of providing medicines use reviews: findings from the national evaluation of the community pharmacy contractual framework. Int J Pharm Pract. 2007;15:B45–B6. https://doi.org/10.1211/096176707781890707.

Brooks D, Hopp A, White S. Perspectives of community pharmacy staff on healthy living pharmacies: a qualitative study. Int J Clin Pharm. 2013;21:16.

Chaar BB, Wang H, Day CA, Hanrahan JR, Winstock AR, Fois R. Factors influencing pharmacy services in opioid substitution treatment. Drug Alcohol Rev. 2013;32:426–34. https://doi.org/10.1111/dar.12032.

Corlett S, Dodds L. The new medicines service; initial views and early experiences of community pharmacists in Kent. Int J Clin Pharm. 2013;21:96–7.

Donovan GR, Paudyal V. England’s Healthy Living Pharmacy (HLP) initiative: facilitating the engagement of pharmacy support staff in public health. Res Social Adm Pharm. 2016;12:281–92. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.sapharm.2015.05.010.

Duarte M, Ferreira P, Soares M, Cavaco A, Martins AP. Community pharmacists’ attitudes towards adverse drug reaction reporting and their knowledge of the new pharmacovigilance legislation in the southern region of Portugal: a mixed methods study. Drugs Ther Perspect. 2015;31:316–22. https://doi.org/10.1007/s40267-015-0227-8.

Elkalmi RM, Hassali MA, Ibrahim MI, Jamshed SQ, Al-Lela OQ. Community pharmacists' attitudes, perceptions, and barriers toward adverse drug reaction reporting in Malaysia: a quantitative insight. J Patient Saf. 2014;10:81–7. https://doi.org/10.1097/pts.0000000000000051.

Elkalmi RM, Hassali MA, Ibrahim MIM, Liau SY, Awaisu A. A qualitative study exploring barriers and facilitators for reporting of adverse drug reactions (ADRs) among community pharmacists in Malaysia. J Pharm Health Serv Res. 2011;2:71–8. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1759-8893.2011.00037.x.

Firth H, Todd A, Bambra C. Benefits and barriers to the public health pharmacy: a qualitative exploration of providers’ and commissioners’ perceptions of the Healthy Living Pharmacy Framework. Perspect Public Health. 2015;135:251–6.

Gauld N, Kelly F, Shaw J. Is non-prescription oseltamivir availability under strict criteria workable? A qualitative study in New Zealand. J Antimicrob Chemother. 2011;66:201–4. https://doi.org/10.1093/jac/dkq409.

Gröber-Grätz D, Gulich M. Impact of drug discount contracts on pharmacies and on patients’ drug supply. J Public Health. 2010;18:583–9. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10389-010-0338-6.

Hammar T, Nystrom S, Petersson G, Rydberg T, Astrand B. Swedish pharmacists value eprescribing: a survey of a nationwide implementation. J Pharm Health Serv Res. 2010;1:23–32. https://doi.org/10.1211/jphsr.01.01.0012.

Hamrosi KK, Raynor DK, Aslani P. Enhancing provision of written medicine information in Australia: pharmacist, general practitioner and consumer perceptions of the barriers and facilitators. BMC Health Serv Res. 2014;14:183. https://doi.org/10.1186/1472-6963-14-183.

Hansford D, Cunningham S, John D, McCaig D, Stewart D. Community pharmacists’ views, attitudes and early experiences of over-the-counter simvastatin. Pharm World Sci. 2007;29:380–5. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11096-007-9084-4.

Hodson K, James D, Smith M, Hughes L, Blenkinsopp A, Cohen D, et al. Evaluation of the discharge medicines review service in Wales: community and hospital pharmacists’ views. Int J Clin Pharm. 2014;22:6. doi: https://doi.org/10.1111/ijpp.12142.

Irujo M, Beitia G, Bes-Rastrollo M, Figueiras A, Hernandez-Diaz S, Lasheras B. Factors that influence under-reporting of suspected adverse drug reactions among community pharmacists in a Spanish region. Drug Saf. 2007;30:1073–82. https://doi.org/10.2165/00002018-200730110-00006.

Kaae S, Søndergaard B, Haugbølle LS, Traulsen JM. The relationship between leadership style and provision of the first Danish publicly reimbursed cognitive pharmaceutical service—a qualitative multicase study. Res Social Adm Pharm. 2011;7:113–21. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.sapharm.2010.03.001.

Kaae S, Sondergaard B, Stig L, Traulsen JM. Sustaining delivery of the first publicly reimbursed cognitive service in Denmark: a cross-case analysis. Int J Pharm Pract. 2010;18:21–7.

Kansanaho H, Puumalainen I, Varunki M, Ahonen R, Airaksinen M. Implementation of a professional program in Finnish community pharmacies in 2000-2002. Patient Educ Couns. 2005;57:272–9. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.pec.2004.07.014.

Latif A, Boardman H. Community pharmacists’ attitudes towards medicines use reviews and factors affecting the numbers performed. Pharm World Sci. 2008;30:536–43.

Latif A, Mahmood K, Boardman H. Medicines use reviews–how have pharmacists’ views changed? Int J Clin Pharm. 2010;18:69–70.

Latif A, Waring J, Watmough D, Barber N, Chuter A, Davies J, et al. Examination of England's New Medicine Service (NMS) of complex health care interventions in community pharmacy. Res Social Adm Pharm. 2016;12:966–89. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.sapharm.2015.12.007.

Lonergan C, O'Grady M, Byrne S. An exploratory study of codeine sales restrictions within Irish pharmacies, a qualitative study. Int J Pharm Pract. 2012;20:43.

Loo RL, Diaper C, Salami OT, Kundu M, Lalkia M, Airhiavbere E, et al. The NHS Health Check: the views of community pharmacists. Int J Pharm Pract. 2011;19:13. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.2042-7174.2011.00142.x.

Lucas B, Blenkinsopp A. Community pharmacists' experience and perceptions of the New Medicines Service (NMS). Int J Pharm Pract. 2015;23:399–406. https://doi.org/10.1111/ijpp.12180.

Paudyal V, Hansford D, Cunningham S, Stewart D. Pharmacists’ perceived integration into practice of over-the-counter simvastatin five years post reclassification. Int J Clin Pharm. 2012;34:733–8. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11096-012-9668-5.

Paudyal V, Hansford D, Scott Cunningham IT, Stewart D. Cross-sectional survey of community pharmacists’ views of the electronic Minor Ailment Service in Scotland. Int J Pharm Pract. 2010;18:194–201. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.2042-7174.2010.00042.x.

Ping CC, March G, Clark A, Gilbert A, Hassali MA, Bahari MB. A web-based survey on Australian community pharmacists’ perceptions and practices of generic substitution. J Generic Med. 2010;7:342–53. https://doi.org/10.1057/jgm.2010.23.

Rahimi B, Timpka T. Pharmacists’ views on integrated electronic prescribing systems: associations between usefulness, pharmacological safety, and barriers to technology use. Eur J Clin Pharmacol. 2011;67:179–84. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00228-010-0936-9.

Rutter P, Vryaparj G. Qualitative exploration of the views of healthy living champions from pharmacies in England. Int J Clin Pharm. 2015;37:27–30. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11096-014-0055-2.

Shevket O, White S. A qualitative follow-up study of the perspectives of community pharmacy staff on Healthy Living Pharmacies. Int J Clin Pharm. 2015;23:69–70.

Thomas T, Hathiari A, Benson C, Oladosu B. Controlled drugs: are they being controlled? An evaluation of the views, understanding and implementation of the amended Controlled Drug Regulations (2006) by community pharmacists. Int J Pharm Pract. 2009;17:75. https://doi.org/10.1211/096176709789037155.

Van Grootheest AC, den Berg LTWJ-v, Mes K. Attitudes of community pharmacists in the Netherlands towards adverse drug reaction reporting. Int J Pharm Pract. 2002;10:267–72. https://doi.org/10.1211/096176702776868460.

Weidmann AE, Cunningham S, Gray G, Hansford D, McLay J, Broom J, et al. Over-the-counter orlistat: early experiences, views and attitudes of community pharmacists in Great Britain. Int J Clin Pharm. 2011;33:627–33. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11096-011-9516-z.

Wilcock M, Harding G. What do pharmacists think of MURs and do they change prescribed medication? Pharm J. 2007;281:163.

Bassi M, Wood K. Medicines use reviews: time for a new name? Int J Pharm Pract. 2009;17(S2):B4–5. https://doi.org/10.1211/096176709789037119.

Gossell-Williams M, Adebayo SA. The pharmwatch programme: challenges to engaging the community pharmacists in Jamaica. Pharm Pract. 2008;6:187–90.

Qassim S, Metwaly Z, Shamsain M, AlHariri Y. Spontaneous reporting of adverse drug reactions in uae: obstacles and motivation among community pharmacists. Int J Pharm Sci Res. 2014;5:4203–8.

Toklu HZ, Uysal MK. The knowledge and attitude of the Turkish community pharmacists toward pharmacovigilance in the Kadikoy district of Istanbul. Pharm World Sci. 2008;30:556–27. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11096-008-9209-4.

Hersberger KE, Renggli VP, Nirkko AC, Mathis J, Schwegler K, Bloch KE. Screening for sleep disorders in community pharmacies -- evaluation of a campaign in Switzerland. J Clin Pharm Ther. 2006;31:35–41. doi: https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1365-2710.2006.00698.x.

CFIR Research Team. Consolidated Framework for Implementation Research: Tools and Templates 2018. Available from: https://cfirguide.org/tools/tools-and-templates/.

Luetsch K. Attitudes and attributes of pharmacists in relation to practice change – a scoping review and discussion. Res Social Adm Pharm. 2017;13:440–55.e11. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.sapharm.2016.06.010.

Wingfield J, Bissell P, Anderson C. The scope of pharmacy ethics-an evaluation of the international research literature, 1990-2002. Soc Sci Med. 2004;58:2383–96. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.socscimed.2003.09.003.

Cooper RJ, Bissell P, Wingfield J. A new prescription for empirical ethics research in pharmacy: a critical review of the literature. J Med Ethics. 2007;33:82–6. https://doi.org/10.1136/jme.2005.015297.

Powers MF, Bright DR. Pharmacy technicians and medication therapy management. J Pharm Technol. 2008;24:336–9. https://doi.org/10.1177/875512250802400604.

Powers MF, Hohmeier KC. Pharmacy technicians and immunizations. J Pharm Technol. 2011;27:111–6. https://doi.org/10.1177/875512251102700303.

Roberts AS, Benrimoj SI, Chen TF, Williams KA, Hopp TR, Aslani P. Understanding practice change in community pharmacy: a qualitative study in Australia. Res Social Adm Pharm. 2005;1:546–64. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.sapharm.2005.09.003.

John C, Brown A. Technicians and other pharmacy support workforce cadres working with pharmacists: United Kingdom case study. Res Social Adm Pharm. 2017;13:297–9. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.sapharm.2016.10.007.

Koehler T, Brown A. Documenting the evolution of the relationship between the pharmacy support workforce and pharmacists to support patient care. Res Social Adm Pharm. 13:280–5. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.sapharm.2016.10.012.

Kilbourne AM, Neumann MS, Pincus HA, Bauer MS, Stall R. Implementing evidence-based interventions in health care: application of the replicating effective programs framework. Implement Sci. 2007;2:42. https://doi.org/10.1186/1748-5908-2-42.

Balasubramanian BA, Cohen DJ, Davis MM, Gunn R, Dickinson LM, Miller WL, et al. Learning evaluation: blending quality improvement and implementation research methods to study healthcare innovations. Implement Sci. 2015;10:31. https://doi.org/10.1186/s13012-015-0219-z.

Blondal AB, Jonsson JS, Sporrong SK, Almarsdottir AB. General practitioners’ perceptions of the current status and pharmacists’ contribution to primary care in Iceland. Int J Clin Pharm. 2017;39:945–52. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11096-017-0478-7.

Moore T, Kennedy J, McCarthy S. Exploring the general practitioner-pharmacist relationship in the community setting in Ireland. Int J Pharm Pract. 2014;22:327–34. https://doi.org/10.1111/ijpp.12084.

Bryant LJM, Coster G, Gamble GD, McCormick RN. General practitioners’ and pharmacists’ perceptions of the role of community pharmacists in delivering clinical services. Res Social Adm Pharm. 2009;5:347–62. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.sapharm.2009.01.002.

Bryant L, Maney J, Martini N. Changing perspectives of the role of community pharmacists: 1998–2012. J Prim Health Care. 2017;9:34–46. https://doi.org/10.1071/HC16032.

Edmunds J, Calnan MW. The reprofessionalisation of community pharmacy? An exploration of attitudes to extended roles for community pharmacists amongst pharmacists and general practioners in the United Kingdom. Soc Sci Med. 2001;53:943–55. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0277-9536(00)00393-2.

Hughes CM, McCann S. Perceived interprofessional barriers between community pharmacists and general practitioners: a qualitative assessment. Br J Gen Pract. 2003;53:600–6.

Naik Panvelkar P, Saini B, Armour C. Measurement of patient satisfaction with community pharmacy services: a review. Pharm World Sci. 2009;31:525–37. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11096-009-9311-2.

Gammie SM, Rodgers RM, Loo RL, Corlett SA, Krska J. Medicine-related services in community pharmacy: public preferences for pharmacy attributes and promotional methods and comparison with pharmacists’ perceptions. Pateint Prefer Adherance. 2016;10:2297–307. https://doi.org/10.2147/PPA.S112932.

Gidman W, Ward P, McGregor L. Understanding public trust in services provided by community pharmacists relative to those provided by general practitioners: a qualitative study. BMJ Open. 2012;2. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmjopen-2012-000939.

Krska J, Morecroft CW. Views of the general public on the role of pharmacy in public health. J Pharm Health Serv Res. 2010;1:33–8. https://doi.org/10.1211/jphsr.01.01.0013.

Cavaco AM, Dias JP, Bates IP. Consumers’ perceptions of community pharmacy in Portugal: a qualitative exploratory study. Pharm World Sci. 2005;27:54–60.

Al-Arifi MN. Patients’ perception, views and satisfaction with pharmacists' role as health care provider in community pharmacy setting at Riyadh, Saudi Arabia. Saudi Pharm J. 2012;20:323–30. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jsps.2012.05.007.

Pinnock H, Barwick M, Carpenter CR, Eldridge S, Grandes G, Griffiths CJ, et al. Standards for Reporting Implementation Studies (StaRI): explanation and elaboration document. BMJ Open. 2017;7. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmj.i6795.

Proctor EK, Powell BJ, McMillen JC. Implementation strategies: recommendations for specifying and reporting. Implement Sci. 2013;8:139. https://doi.org/10.1186/1748-5908-8-139.

Gagnon MP, Nsangou ER, Payne-Gagnon J, Grenier S, Sicotte C. Barriers and facilitators to implementing electronic prescription: a systematic review of user groups' perceptions. J Am Med Inform Assoc. 2014;21:535–41. https://doi.org/10.1136/amiajnl-2013-002203.

Gravel K, Legare F, Graham ID. Barriers and facilitators to implementing shared decision-making in clinical practice: a systematic review of health professionals' perceptions. Implement Sci. 2006;1:16. https://doi.org/10.1186/1748-5908-1-16.

Geerligs L, Rankin NM, Shepherd HL, Butow P. Hospital-based interventions: a systematic review of staff-reported barriers and facilitators to implementation processes. Implement Sci. 2018;13:36. https://doi.org/10.1186/s13012-018-0726-9.

Chaudoir SR, Dugan AG, Barr CH. Measuring factors affecting implementation of health innovations: a systematic review of structural, organizational, provider, patient, and innovation level measures. Implement Sci. 2013;8:22. https://doi.org/10.1186/1748-5908-8-22.

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to thank Elaine Blair for peer reviewing the search method, and Andrew Laird and Nouf Abutheraa for contributing to study selection. Additionally, we appreciate the valuable input of the reviewers which led to the development of the preliminary casual theory presented in this paper.

Funding

This work was funded by the University of Strathclyde as part of NW’s doctoral project, and supported by the Health Foundation Closing the Gap in Patient Safety Programme (Award Reference Number: 7271).

Availability of data and materials

Further data and material is available upon request to the corresponding author.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

NW contributed to the methodological design of the review, underwent the data extraction and analysis, and wrote the first draft of the manuscript. RN and MB contributed to the methodological design of the review. ED contributed to the methodological design of the review and contributed to decisions regarding the quality assessment and study selection. All authors edited and approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

Not applicable.

Consent for publication

Not applicable as this review does not contains any individual person’s data in any form.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Additional files

Additional file 1:

Medline search strategy. (DOCX 27 kb)

Additional file 2:

Consolidated Framework for Implementation Research construct descriptions. (DOCX 21 kb)

Additional file 3:

Characteristics of included studies. (DOCX 69 kb)

Additional file 4:

Full quality assessment results. (DOCX 83 kb)

Additional file 5:

Full presentation of constructs and subconstructs. (DOCX 536 kb)

Additional file 6:

CFIR constructs represented within the different reviews. (DOCX 33 kb)

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made. The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver (http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/) applies to the data made available in this article, unless otherwise stated.

About this article

Cite this article

Weir, N.M., Newham, R., Dunlop, E. et al. Factors influencing national implementation of innovations within community pharmacy: a systematic review applying the Consolidated Framework for Implementation Research. Implementation Sci 14, 21 (2019). https://doi.org/10.1186/s13012-019-0867-5

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s13012-019-0867-5