Abstract

Background

The Medical Research Council framework provides a useful general approach to designing and evaluating complex interventions, but does not provide detailed guidance on how to do this and there is little evidence of how this framework is applied in practice. This study describes the use of intervention mapping (IM) in the design of a theory-driven, group-based complex intervention to support self-management (SM) of patients with osteoarthritis (OA) and chronic low back pain (CLBP) in Ireland’s primary care health system.

Methods

The six steps of the IM protocol were systematically applied to develop the self-management of osteoarthritis and low back pain through activity and skills (SOLAS) intervention through adaptation of the Facilitating Activity and Self-management in Arthritis (FASA) intervention. A needs assessment including literature reviews, interviews with patients and physiotherapists and resource evaluation was completed to identify the programme goals, determinants of SM behaviour, consolidated definition of SM and required adaptations to FASA to meet health service and patient needs and the evidence. The resultant SOLAS intervention behavioural outcomes, performance and change objectives were specified and practical application methods selected, followed by organised programme, adoption, implementation and evaluation plans underpinned by behaviour change theory.

Results

The SOLAS intervention consists of six weekly sessions of 90-min education and exercise designed to increase participants’ physical activity level and use of evidence-based SM strategies (i.e. pain self-management, pain coping, healthy eating for weight management and specific exercise) through targeting of individual determinants of SM behaviour (knowledge, skills, self-efficacy, fear, catastrophizing, motivation, behavioural regulation), delivered by a trained physiotherapist to groups of up to eight individuals using a needs supportive interpersonal style based on self-determination theory. Strategies to support SOLAS intervention adoption and implementation included a consensus building workshop with physiotherapy stakeholders, development of a physiotherapist training programme and a pilot trial with physiotherapist and patient feedback.

Conclusions

The SOLAS intervention is currently being evaluated in a cluster randomised controlled feasibility trial. IM is a time-intensive collaborative process, but the range of methods and resultant high level of transparency is invaluable and allows replication by future complex intervention and trial developers.

Similar content being viewed by others

Background

Highly prevalent chronic musculoskeletal pain conditions, such as osteoarthritis (OA) and chronic low back pain (CLBP), place substantial burdens on individuals, health systems, and economies through their profound impact on physical function, psychosocial well-being, quality of life and productivity [1–3]. Clinical guidelines endorse patient education about the underlying chronic condition and support for self-management (SM) behaviours, including physical activity [4–7], with SM programmes being championed in many health systems [8–10] internationally, but there has been minimal implementation in primary care in Ireland [11]. Contributing factors include variability in how SM is defined in the literature [12], the small effects for interventions in OA [13], the limited evidence base for effective interventions in CLBP [14] management and the diverse case mix of patients in primary care, which limits the time and expertise [15, 16] of physiotherapists tasked with developing such programmes [17]. Furthermore, the variable quality of Ireland’s primary care health system infrastructure and staffing levels present further barriers [11], which taken together have contributed to a ‘second translational gap’ [18].

A systematic review of SM interventions for a range of chronic musculoskeletal pain conditions found that short (<8 weeks), healthcare professional-delivered, group interventions showed some positive effects, but further research of their effectiveness and cost-effectiveness was warranted [19]. The successful implementation of a standardised, evidence-based clinical and cost-effective group programme to support SM for patients with chronic musculoskeletal pain is a key priority for primary care physiotherapy in Ireland [9]; however, a potential intervention must first be demonstrated to be credible, feasible and implementable within this challenging health service context prior to widespread adoption.

Complex interventions, for example, those designed to improve health outcomes by changing SM behaviour, contain several interacting components, as well as variability within the range of possible outcomes and number of behaviours required by those delivering and receiving the intervention [20]. They typically include behavioural support to improve adherence to the desired behaviour and may target both modifications in healthcare provider behaviour relating to how they interact with patients in delivering the intervention and patient behaviour in adopting it. Moreover, the causal chain linking a behavioural support intervention to health outcomes is complex and requires a relevant theoretical model to understand its mechanisms of action [21–23]. This is further challenged by the demands associated with standardising the design and delivery of the intervention, sensitivity to local context, the organisational and logistical difficulties of applying standard experimental methods and the length and complexity of the causal chains [20]. Indeed, it has been acknowledged that ensuring strict standardisation may be inappropriate and the intervention may work better if a specified degree of adaptation to local settings is allowed [20]. Nonetheless, a change in usual clinical practice is often required to ensure successful implementation, notwithstanding the additional complexity of delivering a group intervention [24].

The Medical Research Council (MRC) updated guidelines recommend an iterative, cyclical phased approach to intervention development and evaluation [20, 25–27], noting that ‘too strong an emphasis on the main evaluation to the neglect of adequate development and piloting or consideration of the practical issues of implementation will result in weaker interventions that are harder to evaluate, less likely to be implemented and less likely to be worth implementing’ [20]. Concern for implementation should begin in the design phase through consideration of the barriers and enablers to successful implementation and engagement of key stakeholders through involvement in the design and feasibility processes. The MRC framework provides a useful general approach to designing and evaluating complex interventions, but it does not provide detailed guidance on how to do this [28]. While the evaluation phase is widely reported with improving transparency [29], there are few published examples of how the wider aspects of this framework are applied in practice [30, 31]. Intervention mapping (IM) provides a logical process for intervention development, implementation and evaluation [32] that fulfils the MRC framework criteria and has been previously used to develop [33] and adapt evidence-based SM programmes for other settings [34]. The primary aims of this study were to use the IM process to develop a complex group-based SM intervention (SOLAS: self-management of osteoarthritis and low back pain through activity and skills) for Ireland’s primary care physiotherapy service through adaptation of an existing evidence-based programme (Facilitating Activity and Self-management in Arthritis (FASA) [35]) which would serve as a prototype and to address factors related to its implementation in a planned feasibility trial [36] set in the publicly-funded Health Service Executive Primary Community and Continuing Care (PCCC) physiotherapy services of Dublin, Kildare and Wicklow on the east coast of Ireland serving a population of 1.6 million [37].

Methods

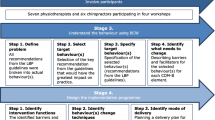

IM is a six-step process with each step consisting of several tasks which once completed inform the next step as detailed in Bartholomew et al. [32] and in Fig. 1.

Intervention mapping process, Bartholomew et al. [32]

-

Step one: needs assessment

-

The aim of step 1 was to develop programme goals for the intervention related to health and quality of life based on a detailed multi-method assessment of the needs of the PCCC physiotherapy service providers and patients and the literature regarding SM for chronic musculoskeletal pain to establish how an intervention could be designed to meet these needs.

-

Semi-structured interviews

-

Individual semi-structured, qualitative interviews were conducted with all consenting physiotherapy managers (n = 10) in the catchment area of the feasibility trial and a sample of consenting patients with CLBP and/or spinal OA (n = 6) who had recently participated in a group-based physiotherapy programme to understand their needs in relation to a SM intervention. Both studies were approved by the UCD Human Research Ethics Committee-Sciences (Ref no: LS-E-13-103-Hurley-Osing; Ref no: LS-13-25-Toomey-Hurley-Osing). Deductive thematic analysis based on Braun and Clarke’s method [38] was conducted on the data using the Theoretical Domains Framework (TDF) [39]. The TDF is a validated integrative framework that synthesised key theoretical constructs from 33 behaviour change theories into 14 domains that supports the identification and selection of relevant determinants of behaviour for targeting within interventions. An additional file provides details of the interview topic guides and coding frames (see Additional file 1).

-

-

Literature reviews

-

A thematic analysis of chronic disease SM definitions was conducted to reach a consolidated definition. This process is shown in detail in an additional file (see Additional file 2). This definition was then applied to a rapid review of the effectiveness of physiotherapy delivered group-based SM programmes for OA and CLBP, which was lacking in the literature. An intervention prototype was identified for further adaptation based on its evidence base, similarities in health service context and relevance to the target populations. The most recent international clinical guideline recommendations relating to programme content and SM behaviour for OA and CLBP were reviewed. The behavioural determinants of outcomes of SM interventions identified in recent systematic reviews within the target populations, general behaviour change theories, and behaviour change theories and techniques (BCTs) reported in systematic reviews of SM interventions and our rapid review [40] were reviewed for their relevance to targeting and supporting adherence to SM behaviours [41]. The intervention prototype was then compared to the literature to identify necessary adaptations for SOLAS.

-

-

Focus groups

-

Two focus groups with purposively selected consenting physiotherapists (n = 28) working in the catchment area were conducted to explore the feasibility of delivering the intervention prototype and the barriers and enablers to be addressed to support intervention implementation and uptake by participants. This study was approved by the UCD Human Research Ethics Committee-Sciences (Ref no: LS-E-13-103-Hurley-Osing). Deductive thematic analysis based on Braun and Clarke’s method [38] was conducted on the data using two coding frames (feasibility and TDF, see Additional file 1). Table 1 shows the operational definitions of feasibility that were used in this study. Proposed changes to the intervention prototype were then addressed during a consensus building workshop outlined in step 4 below.

Table 1 Operational definitions of feasibility aspects related to intervention delivery [adapted from Bowen et al. [70] -

Physiotherapy managers (n = 10) completed a resource capacity checklist to identify the practicality of delivering the intervention prototype within their local service settings within the feasibility trial. An additional file shows this process in more detail (see Additional file 3).

-

The needs assessment provided the information needed to specify the SOLAS programme goals, the desired SM behaviours it would aim to change within participants and the discrepancies between the selected prototype and the additional content and theoretical underpinnings needed in SOLAS based on the literature and local needs. It also informed the feasibility and necessary modifications to primary care sites to support implementation of SOLAS in the planned trial.

-

-

-

Step two: identification of outcomes, performance objectives and change objectives

-

The behavioural outcomes to be achieved by the SOLAS intervention were developed, and performance objectives (i.e. what a participant has to learn, do or change to achieve the specified outcomes) were stated for each behavioural outcome [32]. Using the information gathered from the needs assessment, the determinants of each behavioural outcome were identified and linked to relevant performance objectives creating a matrix of change objectives that detail what needs to change in the identified determinants to achieve the performance objective.

-

-

Step three: selecting methods and practical applications

-

To operationalise the change objectives into practical applications, theoretically informed methods were selected, i.e. each determinant linked to a change objective was mapped to a TDF domain [39], and appropriate intervention methods (i.e. BCTs) were selected. BCTs are intervention components designed to influence the causal determinants that regulate behaviour [42]. This BCT identification process was conducted using appropriate literature [39, 40, 43], extensive discussion by the intervention development group and expert consultation (S Dean, L Atkins). The intervention prototype was reviewed for the specified BCTs, and any omissions were added to SOLAS. The selected BCTs were then converted into practical applications that could be implemented within SOLAS, taking into account the context and environment in which it was being delivered.

-

-

Step four: creating an organised programme plan

-

A consensus building workshop was convened with physiotherapy stakeholders (n = 6 managers, 36 physiotherapists) working within all nine PCCC areas for final agreement on the adaptations needed to the intervention prototype structure to devise the SOLAS programme plan, as well as procedures to enhance implementation within the feasibility trial, i.e. physiotherapist training needs. Proposals on which consensus was reached (8/9 PCCC areas voted in favour) were incorporated into the SOLAS intervention design. The definitive intervention content and materials were adapted from the intervention prototype and relevant additions made.

-

-

Step five: adoption and implementation plan

-

The programme use outcomes to achieve successful adoption by physiotherapy managers and implementation by clinical physiotherapists of the SOLAS intervention within the feasibility trial were specified. The determinants of programme adoption and implementation were identified from the TDF analysis of the qualitative studies within the needs assessment and linked to each performance objective to create a matrix of change objectives. The change objectives were converted into practical applications using a range of evidence-based BCTs [43, 44].

-

-

Step six: creating an evaluation plan

-

The evaluation plan for SOLAS followed the recommended approach to establish the effect of the intervention on the target SM behaviours within a feasibility trial before moving to a definitive effectiveness trial [21]. This involved the specification of feasibility process and effect evaluation objectives, selection and development of indicators and outcome measures and a comprehensive feasibility trial design including treatment fidelity protocol. All procedures were tested in a pilot trial (UCD Human Research Ethics Committee-Sciences Ref no: LS-13-54-Currie-Hurley) to assess their acceptability and identify further adaptations during the development phase to enhance implementation during the feasibility trial. The pilot trial (April–Aug 2014) was run in four primary care health areas involving eight consenting physiotherapists and 20 consenting participants (12 F:8 M; mean (SD) age, 59.7 (8.9) years) and included individual semi-structured interviews with a sample of physiotherapists (n = 3) and participants (n = 5).

-

Results

-

Step one: needs assessment

-

The key findings of the multi-method needs assessment are provided below. An additional file shows these results in more detail (see Additional file 4).

-

Semi-structured interviews

-

The main themes from the manager interviews related to the TDF domains environmental context and resources (i.e. high caseload of patients with CLBP and OA requiring support to self-manage; important role but limited availability of psychologists to contribute to SM programmes), skills (staff experienced in running other groups), intention to support staff to set up group SM programmes and positive beliefs about the consequences of such programmes for patients and staff. The patients were positive about the experience of group physiotherapy (social influences), gained understanding of their condition (knowledge), skills and confidence in its SM (beliefs about capabilities), but would have liked it to be longer than 6 weeks (environmental context and resources) for further support.

-

-

Literature reviews

-

The consolidated definition of an intervention that promotes SM was designed to address both the process and outcomes related to SM that the SOLAS intervention could address (see Additional file 4). The rapid review found comparable effectiveness of physiotherapist-led group education and exercise interventions and individual physiotherapy or medical management for pain and disability outcomes in OA or CLBP [12]. Nonetheless, the high priority raised by physiotherapy managers to implement an evidence-based group SM programme rather than continuing with individual treatment and the putative beneficial effects of group-based SM programmes [19] confirmed our decision to develop a group SM programme that would meet the needs of the local population. From the rapid review, the FASA intervention [35] was selected as the prototype for adaptation that fulfilled our consolidated SM definition, being an education and exercise intervention based on the evidence-based ESCAPE programme for OA knee [45], designed for people aged over 50 years with OA hip, knee and/or lumbar spine, which has been found to be clinically effective compared to standard general practitioner (GP) care (personal communications, N Walsh). FASA was designed to be delivered by one physiotherapist in groups of up to eight people and considered acceptable and feasible to support SM by healthcare professionals in the UK [46]. In the FASA trial, it was delivered by trained research physiotherapists in UK healthcare settings and had not been previously delivered by health service physiotherapists in any jurisdiction including Ireland. We contacted the FASA intervention developer (N Walsh) who agreed to collaborate, provided and discussed the intervention materials, and allowed our team to observe its delivery in several UK settings. From this, we believed it had the potential to meet our target population and health service needs but would need formal evaluation to establish if it was fit for purpose, acceptable to Irish primary care physiotherapists and required adaptation prior to evaluation in the planned feasibility trial.

-

Within the most recent clinical guideline recommendations for OA and CLBP, the most consistent SM behaviours for programmes to promote/change within participants were a continuation or increase in physical activity, the use of joint specific exercise and pharmacological and non-pharmacological pain management approaches, with varying recommendations for healthy eating/weight management and pacing for OA and the use of active coping strategies for CLBP. The strategies that interventions should adopt to support SM behaviour ranged from none [5, 7] to highly specific [4, 47]. An additional file provides details of these findings (see Additional file 5). Three psychological factors that mediated (i.e. determinants) pain, disability and functional outcomes of interventions targeting these SM behaviours in chronic musculoskeletal pain were identified from the literature, i.e. increasing self-efficacy for OA and CLBP [48, 49], and reducing pain catastrophizing [48, 50] and fear [51] for CLBP. The literature reviews of behaviour change theories and techniques found variable integration in included studies, with social cognitive theory being the most frequently applied, and identified the most commonly used BCTs in group-based SM programmes as outlined in Additional file 4.

-

-

Focus groups

-

Following inter-rater reliability checks (>95 % agreement) [52], the focus groups resulted in 29 themes related to feasibility: programme participants (n = 5), content (n = 7), structure (n = 9) and delivery (n = 8). The most frequent theme was the feasibility of recruiting sufficient numbers of suitable participants, at the right time to participate, with varying views expressed on the optimal number for a successful group [6–14]. Opinions were mixed about the acceptability of including participants with CLBP, in addition to OA, and those below 50 years as within FASA [35], but considered essential to recruiting sufficient patients to ensure the intervention’s long-term viability. Physiotherapists were positive about the combined SM education and patient-led group exercise model of FASA, but felt 20 min was insufficient for education and discussion, 1 h was too short to run the group effectively, and two sessions per week as delivered in FASA while ideal was not acceptable from service or patient perspectives. An additional file provides further details of the feasibility analysis (see Additional file 6).

-

The findings of the barriers and enablers analysis identified 13 of the 14 TDF domains and 30 themes that predominantly related to the physiotherapists (n = 13) who would deliver the intervention, the target participants (n = 10), the intervention (n = 3), GPs (n = 2) and local organisations (n = 2). The majority of perceived barriers to delivering the intervention prototype were within the TDF environmental context and resources domain, beliefs about capabilities to deliver the intervention as intended and beliefs about its consequences. The key enablers were similar to the findings of the manager interviews. The significant influence of referring GPs as potential barriers and enablers to changing client attitudes, beliefs and expectations of the role of physiotherapy in promoting SM were also highlighted. From the participant perspective, the main barriers perceived by physiotherapists to be addressed were patients’ limited knowledge and skills in engaging in SM behaviours, particularly physical activity and exercise, low motivation to self-manage and regulate their behaviour and negative emotions about participating in a group. Further details of these findings are provided in an additional file (see Additional file 4).

-

The resource capacity checklist findings showed that most physiotherapy sites (95 %; n = 19) met the criteria to be considered eligible (≥60 %) to deliver the intervention prototype within existing capabilities or with essential modifications to facilities, equipment or staffing. Further details of these findings are provided in additional files (see Additional files 3 and 4).

-

Following this detailed needs assessment, the overall programme goal of SOLAS was defined as promoting SM behaviour for people with OA hip/knee, lumbar spine and/or CLBP in everyday life. The findings of the needs assessment informed several key decisions in designing the intervention. One, a number of determinants of the outcome of SM interventions in people with OA and CLBP identified from the literature (self-efficacy, motivation, catastrophizing, fear), focus groups (knowledge, skills, motivation, fear, behaviour-regulation) and expert consultation (behaviour regulation) were to be targeted within SOLAS (two of which were absent from FASA, i.e. catastrophizing, motivation; see Table 2) as outlined in Fig 2. Two, a specific behaviour change theory, self-determination theory (SDT), was selected to underpin participants’ uptake and engagement in the SOLAS intervention target behaviours as non-adherence to physical activity, exercise and diet is well recognised in the literature in these populations [53, 54]. SDT emphasises the importance of autonomy and autonomous self-regulation, core components of self-management behaviour [55–57]. According to SDT, social agents such as healthcare practitioners can influence an individual’s autonomous motivation for behaviour through their interpersonal style and interaction with the individual. A supportive interpersonal style satisfies an individual’s psychological need for autonomy, competence and relatedness leading to increased levels of autonomous motivation for the behaviour. Previously, SDT has been successfully applied to group-based education, exercise [58–61], physical activity [62], weight management [63], medication adherence [64], diabetes SM [65] and individual physiotherapy interventions [40, 66–68]. Several needs-supportive interpersonal strategies were identified from the literature to support physiotherapists’ effective delivery of the intervention using an SDT approach [58, 66, 67, 69] that would be operationalised during the physiotherapist training programme (step 5); e.g. providing meaningful rationale for SM behaviours, acknowledging participants’ feelings and perspectives and offering opportunities for participant input. Three, although the intervention prototype was found to be broadly consistent with current guidelines for OA, the SOLAS intervention would address the need for more evidence-based information on healthy weight, nutraceuticals and acupuncture [6]. Four, as FASA was not designed for non-specific CLBP, additional education content on the nature of CLBP, active coping strategies and current recommendations for acupuncture and TENS were needed. Finally, the education content required adaptation to reflect socio-demographic statistics related to physical activity, obesity, OA and LBP within the Irish population [3]. An additional file details the process of adapting the SOLAS intervention (see Additional file 5).

Table 2 Determinants of self-management behaviour and behaviour change techniques

-

-

-

Step two: identification of outcomes, performance objectives and change objectives

-

The specific intervention SM behavioural outcomes are:

-

i. To increase the physical activity level of participants

-

ii. To increase the use of evidence-based SM strategies by participants

-

-

Specific performance objectives were developed for the behavioural outcomes related to physical activity (n = 8) and use of SM strategies (n = 5) as detailed in Table 3. Using the information from step 1, the selected determinants were mapped to the performance objectives to articulate the specific change objectives of the intervention. For example, a performance objective for participants to ‘accept the benefits of physical activity’ was linked to the determinant of knowledge and resulted in a change objective ‘develops an understanding of the benefits of physical activity.’ Each change objective was written with an action verb followed by a statement of what is expected to occur as a result of the intervention [32]. An additional file shows this process in detail for all 13 performance objectives (see Additional file 7).

Table 3 Desired behavioural outcomes and performance objectives of the SOLAS intervention

-

-

Step three: selecting methods and practical applications

-

A full list of the selected BCTs and how they map to particular determinants is presented in Table 2. For example, the determinant self-efficacy along with the performance objective participants ‘perform selected physical activity’ was linked to the change objective, participants ‘improve self efficacy in ability to engage in selected physical activities’. The BCTs used to target this change objective ranged from ‘feedback’ and ‘self-monitoring of the behaviour’ to ‘behavioural practice’. These BCTs were translated into practical applications including group discussion and physiotherapist feedback on the previous week’s physical activity behaviour, a diary to self-monitor and review progress and opportunities to practice related activities in and outside the group. Table 4 provides a detailed description of how the selected BCTs were mapped to the change objectives and translated into a range of practical intervention applications.

Table 4 Intervention map linking change objectives to methods and practical applications

-

-

Step four: creating an organised programme plan

-

The consensus building workshop held nine ballots for proposed adaptations to the FASA prototype structure, physiotherapist training and participant recruitment procedures of which eight were carried (Table 5). It was agreed that the definitive SOLAS intervention would comprise six weekly sessions of 90 min (45 min education/discussion and 45 min exercise) for people aged at least 45 years to be delivered by one physiotherapist in groups of four to eight participants with OA of the hip, knee, lumbar spine and CLBP. The adapted education content was incorporated into the new structure (Table 6), and new programme materials were adapted from FASA (i.e. intervention slides and script, participant programme handbook, exercise photographs of an age appropriate model). A review of FASA for evidence-based materials to enhance physical activity, healthy eating, weight management and pain coping strategies (see Additional file 5) identified the need for additions to SOLAS as indicated in Table 6.

Table 5 Consensus building workshop results Table 6 Comparison of FASA and SOLAS interventions

-

-

Step five: adoption and implementation plan

-

The programme use outcomes are:

-

i. PCCC physiotherapy managers adopt the SOLAS intervention and participant recruitment procedures.

-

ii. PCCC physiotherapists implement the SOLAS intervention and participant recruitment procedures.

-

-

The specific performance objectives for each programme use outcome are presented in Table 7. The determinants of physiotherapist behaviour identified from the needs assessment were mapped to the performance objectives to articulate the specific change objectives. An additional file shows the matrix of change objectives in detail (see Additional file 8). A range of theoretically derived BCTs and practical strategies were selected by the intervention development group to target the change objectives of adoption and implementation as detailed in Table 8. For example, in order to influence the determinants physiotherapists’ knowledge, skills, beliefs about capabilities and beliefs about consequences to deliver the SOLAS intervention linked to the performance objective physiotherapists ‘complete training in the delivery of the SOLAS intervention’, a bespoke training programme underpinned by selected BCTs was developed.

Table 7 Programme use outcomes and performance objectives for adoption and implementation Table 8 Programme adoption and implementation of SOLAS intervention and participant recruitment linking change objectives to practical applications

-

-

Step six: creating an evaluation plan

-

A cluster randomised controlled feasibility trial has been designed to evaluate SOLAS (Current Controlled Trials ISRCTN49875385, 26th March 2014) [36]. A cluster randomised trial design was chosen to avoid contamination of the control group [25]. The most appropriate comparison was considered usual treatment [20], defined as individual physiotherapy care. The trial aims to assess the acceptability and demand of the SOLAS intervention to patients and physiotherapists compared to usual treatment [70], the feasibility of trial procedures and the most efficient and effective study design for a definitive trial. In the absence of a suitable validated SM outcome measure from the literature [12, 71, 72], a new measure was developed for evaluation within the feasibility trial. A range of effect and mediation outcome measures were selected from the literature to be evaluated within the trial. A detailed fidelity protocol has been developed and published separately [73]. The pilot trial resulted in further minor adaptations to the intervention content and materials, enhanced physiotherapist training from 1.5 to 2 days (more emphasis on goal setting, problem solving, and feedback) and amended participant eligibility criteria (CLBP participants age ≤30 years) prior to commencement of the main feasibility trial in September 2014.

-

Discussion

This study provides a detailed example of the systematic application of the IM protocol to develop the SOLAS theory-driven evidence-based group intervention to promote self-management in people with OA hip/knee and/or CLBP through adaptation of an existing evidence-based programme. There is currently limited literature on the detailed reporting of the critical development phase of complex interventions in primary healthcare and the application of IM in chronic musculoskeletal pain or physiotherapy, and this study should inform future researchers in this evolving field. We followed all the recommended steps within IM [32], engaged a representative sample of stakeholders using a mix of qualitative and quantitative methods, applied emerging behaviour change methodologies to inform SOLAS intervention development and implementation and adhered to TIDieR guidance in its description [26, 74]. We believe that the decision to adapt an existing intervention enhanced its uptake by stakeholders, the quality of the intervention and materials and allowed the intervention development group to address the practicalities of implementation, including physiotherapist training from the outset.

The SOLAS intervention provides for the first time a group intervention for people with two of the most common chronic musculoskeletal conditions (i.e. OA and CLBP) presenting to primary care. While the multi-joint aspect of the FASA prototype for people with OA aged over 50 years was acceptable to UK physiotherapists [46], and credible to Ireland’s stakeholder primary care physiotherapists, it was considered necessary to adapt the diagnostic pool for SOLAS to include people with non-specific CLBP aged at least 30 years to increase its acceptability to meet their service needs. Further adaptations were required to implement recent clinical guideline recommendations for OA and CLBP and Irish sociodemographic statistics. Finally, the overall structure of the programme was adapted from 12 twice weekly, 1-h sessions to 6 once weekly, 90-min sessions despite some patients and physiotherapists expressing support for a longer programme. Nonetheless, the majority of physiotherapists believed that 6 weeks reflected current practice and was more realistic for patients, which is supported by a recent systematic review [75]. However, it has been proposed that longer programmes may provide larger treatment effects [13, 14, 75], which could be considered worthwhile by patients [76]. Similarly, the decision to deliver the intervention once rather than the more frequent twice weekly reported in the literature [75] was taken to enhance acceptability to local physiotherapist stakeholders as demonstrated in a quote from one focus group participant ‘twice a week is…a nice idea. What you use in trials and then never use in practice’. The feasibility trial results will inform whether these decisions were correct and reflect the reality of collaborating with healthcare professional stakeholders in developing interventions while also taking account of the evidence. If positive, this pragmatic example of involving clinicians has the potential to enhance future knowledge translation of evidence-based interventions, which is highly variable [18], and potentially hampered by previously prioritising the role of clinicians as intervention deliverers to the detriment of harnessing their invaluable contribution in the design phase. Using the IM process to also understand and address the barriers to recruiting and retaining sufficient participants, the identification of sufficient numbers of suitable clinical sites, required adaptations to facilities, equipment and staffing and training requirements to support consistent intervention delivery across a range of primary care health settings enhanced our readiness to evaluate the intervention in the feasibility trial.

As demonstrated in this paper, the IM process details how accessing and using theory can be undertaken to support intervention development and implementation as highlighted in the MRC framework [20]. The application of this approach allows for meaningful analysis of the underlying mechanisms that are hypothesised to affect the desired intervention outcomes, by enabling the explicit linking of intervention components to theory, which should lead to improved outcomes for the targeted populations and an enhanced potential for intervention replication [28]. Our rapid review found that the majority of previous group-based SM interventions failed to report any underpinning behaviour change theory or techniques [40], reducing understanding of mechanisms of action, preventing replication and potentially contributing to their small effects [13, 75, 76]. This was compounded by the limited and variable quality of mediation studies for the target SM behaviours in OA and CLBP [48–51, 77] that required our pragmatic selection of behavioural determinants that could be targeted by the intervention. While self efficacy is an important determinant of physical activity in the general population and older adults with some evidence in OA and CLBP [48, 49], the more tenuous evidence for the effects of fear and catastrophizing [50, 51] on SM outcomes warrants further investigation in appropriately designed and powered prospective mediation studies [75]. Motivation was identified as a key determinant of SM behaviour and enhanced within the intervention by selecting SDT rather than other theoretical perspectives due its primary focus on an individual’s need for autonomy, a core component of SM. Other prominent psychological theories identified in our literature review [40, 75], such as social cognitive theory [78] (which was applied within FASA [35]), predominantly target constructs such as self efficacy, conceptually similar to competence within SDT [79], rather than autonomy. It was also considered unnecessary to include an additional behaviour change theory to target some of the other determinants, as SDT has been found to positively influence other mediators (i.e. fear) related to treatment [80], and the TDF provides a sound theoretical basis for targeting all our selected mediators. Furthermore, the evidence for the determinants of increasing participants’ SM knowledge and skills exemplified in our consolidated definition and highlighted in the physiotherapist focus groups was limited by their poor measurement in previous studies that should be addressed in future research [12, 81].

The study is limited by comparatively less engagement with people with OA and CLBP in the intervention development process that may have increased the acceptability and sustainability of the intervention, but will be addressed in the feasibility trial [36]. While it would have been preferable to specify the target behaviours in a more detailed way, most current OA and CLBP guidelines lack specificity in relation to physical activity and dietary changes for weight management [7, 82]. Indeed, recent evidence has reported health gains in those achieving below recommended physical activity levels [83, 84], and there is general consensus that due to concerns about pain exacerbation, people with chronic musculoskeletal pain should be supported to do activity according to their abilities [85, 86], as we have previously demonstrated in CLBP [87]. Nonetheless, the intervention included public health recommendations for 150 min of moderate intensity physical activity, as well as healthy eating and weight management guidance in addition to relevant statistics for the Irish population to promote behaviour change. While recommendations for resistance and flexibility exercises on 2 or 3 days each week [88] were conveyed to participants during SOLAS, they could have been specified more explicitly within the target behaviours without undermining autonomous motivation. In relation to the remaining SM behaviours, recent trials reporting positive effects have failed to quantify the use of pain coping skills, pharmacological or non-pharmacological pain management strategies by participants, thus limiting our ability to specify targets [89–91]. Within the feasibility trial, the proportion of participants achieving recommended levels of physical activity and using the SM behaviours will be explored to allow their specification for a future definitive trial. Finally, potential socio-cultural and environmental determinants of physical activity and diet in the general population were not specifically addressed within our intervention due to lack of evidence [92–94].

Conclusions

This study provides a detailed example of the application of the IM approach to the development of a theory-driven, group-based complex intervention designed to promote self-management, for evaluation in a feasibility trial. While IM is a time-intensive collaborative process, the range of methods and resultant high level of transparency is invaluable and allows replication by future complex intervention and trial developers.

Availability of supporting data

The data sets supporting the results of this article are included within the article and its additional files.

Abbreviations

- BCT:

-

behaviour change technique

- CLBP:

-

chronic low back pain

- FASA:

-

Facilitating Activity and Self-management in Arthritis

- GP:

-

general practitioner

- IM:

-

intervention mapping

- MRC:

-

Medical Research Council

- OA:

-

osteoarthritis

- PCCC:

-

Primary, Community and Continuing Care

- SDT:

-

self-determination theory

- SM:

-

self-management

- SOLAS:

-

self-management of osteoarthritis and low back pain through activity and skills

- TDF:

-

Theoretical Domains Framework

- TENS:

-

transcutaneous electrical nerve stimulation

References

Cross M, Smith E, Hoy D, Nolte S, Ackerman I, Fransen M, et al. The global burden of hip and knee osteoarthritis: estimates from the global burden of disease 2010 study. Ann Rheum Dis. 2014; doi:10.1136/annrheumdis-2013-204763.

Hoy D, March L, Brooks P, Blyth F, Woolf A, Bain C, et al. The global burden of low back pain: estimates from the Global Burden of Disease 2010 study. Ann Rheum Dis. 2014; doi:10.1136/annrheumdis-2013-204428.

Nolan A, O’Regan C, Dooley C, Wallace D, Hever A, Cronin H, et al. The over 50s in a changing Ireland: economic circumstances, health and well-being. Dublin: Trinity College: The Irish Longitudinal Study on Ageing; 2014.

Fernandes L, Hagen KB, Bijlsma JW, Andreassen O, Christensen P, Conaghan PG, et al. EULAR recommendations for the non-pharmacological core management of hip and knee osteoarthritis. Ann Rheum Dis. 2013; doi:10.1136/annrheumdis-2012-202745.

McAlindon TE, Bannuru RR, Sullivan MC, Arden NK, Berenbaum F, Bierma-Zeinstra SM, et al. OARSI guidelines for the non-surgical management of knee osteoarthritis. Osteoarthritis Cartilage. 2014; doi:10.1016/j.joca.2014.01.003.

National Institute for Health and Care Excellence: CG177—osteoarthritis: care and management. 2014. www.nice.org.uk/cg177. Accessed 10 June 2015.

Savigny P, Watson P, Underwood M. Early management of persistent non-specific low back pain: summary of NICE guidance. BMJ. 2009; doi:10.1136/bmj.b1805.

Department of Health. Supporting people with long term conditions: an NHS and social care model to support local innovation and integration. Department of Health, Leeds. 2005. http://www.leeds.ac.uk/lpop/Key%20Policy%20Documents/supportingLTCs.pdf. Accessed 15 April 2016

Health Service Executive (HSE): framework for self-management support, long-term health conditions: HSE National Advocacy Unit; 2012. http://health.gov.ie/wp-content/uploads/2014/03/tackling_chronic_disease.pdf Accessed 10 March 2014.

Naylor C, Imison C, Goodman N, Buck D, Curry N, Addicott R. Transforming our health care system. Kings Fund: Ten priorities for commissioners; 2011.

O'Donoghue G, Cunningham C, Murphy F, Woods C, Aagaard-Hansen J. Assessment and management of risk factors for the prevention of lifestyle-related disease: a cross-sectional survey of current activities, barriers and perceived training needs of primary care physiotherapists in the Republic of Ireland. Physiotherapy. 2014; doi:10.1016/j.physio.2013.10.004.

Toomey E, Currie-Murphy L, Matthews J, Hurley DA. The effectiveness of physiotherapist-delivered group education and exercise interventions to promote self-management for people with osteoarthritis and chronic low back pain: a rapid review part I. Man Ther. 2015; doi:10.1016/j.math.2014.10.013.

Kroon FP, van der Burg LR, Buchbinder R, Osborne RH, Johnston RV, Pitt V. Self‐management education programmes for osteoarthritis. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2014; doi:10.1002/14651858.

Taylor SJC, Pinnock H, Epiphaniou E, Pearce G, Parke HL, Schwappach A, et al. A rapid synthesis of the evidence on interventions supporting self-management for people with long-term conditions: PRISMS—Practical systematic Review of Self-Management Support for long-term conditions. Health Serv Del Res. 2014;2:275–300.

Department of Health and Children. Primary care: a new direction; quality and fairness-a health system for you; health strategy. Dublin: The Stationery Office; 2001.

Health Service Executive: HSE Transformation Programme … to enable people live healthier and more fulfilled lives. Easy access - public confidence - staff pride: Health Service Executive Population Health Strategy; 2008. www.hse.ie/eng/about/who/population_health/population_health_approach/population_health_strategy_july_2008.pdf. Accessed 10 March 2014

McMahon S, Cusack T, O'Donoghue G. Barriers and facilitators to providing undergraduate physiotherapy clinical education in the primary care setting: a three-round Delphi study. Physiotherapy. 2014; doi:10.1016/j.physio.2013.04.006.

Lau R, Stevenson F, Ong BN, Dziedzic K, Eldridge S, Everitt H, et al. Addressing the evidence to practice gap for complex interventions in primary care: a systematic review of reviews protocol. BMJ Open. 2014; doi:10.1136/bmjopen-2014-005548.

Carnes D, Homer KE, Miles CL, Pincus T, Underwood M, Rahman A, et al. Effective delivery styles and content for self-management interventions for chronic musculoskeletal pain: a systematic literature review. Clin J Pain. 2012; doi:10.1097/AJP.0b013e31822ed2f3.

Craig P, Dieppe P, Macintyre S, Michie S, Nazareth I, Petticrew M, et al. Developing and evaluating complex interventions: the new Medical Research Council guidance. BMJ. 2008; doi:10.1136/bmj.a1655.

Courneya KS. Efficacy, effectiveness, and behavior change trials in exercise research. Int J Behav Nutr Phys. 2010;7:81.

Dziedzic KS, Healey EL, Porcheret M, Ong BN, Main CJ, Jordan KP, et al. Implementing the NICE osteoarthritis guidelines: a mixed methods study and cluster randomised trial of a model osteoarthritis consultation in primary care—the Management of OsteoArthritis In Consultations (MOSAICS) study protocol. Implement Sci. 2014; doi:10.1186/s13012-014-0095-y.

Prestwich A, Sniehotta FF, Whittington C, Dombrowski SU, Rogers L, Michie S. Does theory influence the effectiveness of health behavior interventions? Meta-analysis. Health Psychol. 2014; doi:10.1037/a0032853.

Hoddinott P, Allan K, Avenell A, Britten J. Group interventions to improve health outcomes: a framework for their design and delivery. BMC Public Health. 2010; doi:10.1186/1471-2458-10–800.

Campbell M, Fitzpatrick R, Haines A, Kinmonth AL, Sandercock P, Spiegelhalter D, et al. Framework for design and evaluation of complex interventions to improve health. BMJ. 2000; doi:10.1136/bmj.321.7262.694.

Hoffmann TC, Glasziou PP, Boutron I, Milne R, Perera R, Moher D, et al. Better reporting of interventions: template for intervention description and replication (TIDieR) checklist and guide. BMJ. 2014; doi:10.1136/bmj.g1687.

Moore GF, Audrey S, Barker M, Bond L, Bonell C, Hardeman W, et al. Process evaluation of complex interventions: Medical Research Council guidance. BMJ. 2015; doi:10.1136/bmj.h1258.

French SD, Green SE, O'Connor DA, McKenzie JE, Francis JJ, Michie S, et al. Developing theory-informed behaviour change interventions to implement evidence into practice: a systematic approach using the Theoretical Domains Framework. Implement Sci. 2012; doi:10.1186/1748-5908-7-38.

Mohler R, Bartoszek G, Meyer G. Quality of reporting of complex healthcare interventions and applicability of the CReDECI list—a survey of publications indexed in PubMed. BMC Med Res Methodol. 2013; doi:10.1186/1471-2288-13-125.

Farquhar MC, Ewing G, Booth S. Using mixed methods to develop and evaluate complex interventions in palliative care research. Palliative Med. 2011; doi:10.1177/0269216311417919.

Aventin A, Lohan M, O'Halloran P, Henderson M. Design and development of a film-based intervention about teenage men and unintended pregnancy: applying the Medical Research Council framework in practice. Eval Program Plann. 2015;49:19–30.

Bartholomew LK, Parcel GS, Kok G, Gottlieb NH. Planning health promotion programs: an intervention mapping approach. 3rd ed. San Francisco: Jossey Bass; 2011.

Vermeulen SJ, Anema JR, Schellart AJ, van Mechelen W, van der Beek AJ. Intervention mapping for development of a participatory return-to-work intervention for temporary agency workers and unemployed workers sick-listed due to musculoskeletal disorders. BMC Public Health. 2009; doi:10.1186/1471-2458-9-216.

Detaille SI, van der Gulden JW, Engels JA, Heerkens YF, van Dijk FJ. Using intervention mapping (IM) to develop a self-management programme for employees with a chronic disease in the Netherlands. BMC Public Health. 2010; doi:10.1186/1471-2458-10-353.

Walsh N, Cramp F, Palmer S, Pollock J, Hampson L, Gooberman-Hill R, et al. Exercise and self-management for people with chronic knee, hip or lower back pain: a cluster randomised controlled trial of clinical and cost-effectiveness. Study protocol. Physiotherapy. 2013; doi:10.1016/j.physio.2012.09.002

Hurley DA, Hall AM, Currie-Murphy L, Pincus T, Kamper S, Maher C, et al. Theory-driven group-based complex intervention to support self-management of osteoarthritis and low back pain in primary care physiotherapy: protocol for a cluster randomised controlled feasibility trial (SOLAS). BMJ Open. 2016; doi:10.1136/bmjopen-2015-010728.

Central Statistics Office. Population classified by area. Government of Ireland, 2012. http://www.cso.ie/en/index.html Accessed 20 July 2014.

Braun V, Clarke V. Using thematic analysis in psychology. Qual Res Psychol. 2006; doi:10.1191/1478088706qp063oa.

Cane J, O'Connor D, Michie S. Validation of the theoretical domains framework for use in behaviour change and implementation research. Implement Sci. 2012; doi:10.1186/1748-5908-7-37.

Keogh A, Tully MA, Matthews J, Hurley DA. A review of behaviour change theories and techniques used in group based self-management programmes for chronic low back pain and arthritis. Man Ther. 2015; doi:10.1016/j.math.2015.03.014.

Michie S, West R, Campbell R, Brown J, Gainforth H. ABC of behaviour change theories. An essential resource for researchers, policy makers and practitioners. United Kingdom: Silverback Publishing; 2014.

Michie S, Richardson M, Johnston M, Abraham C, Francis J, Hardeman W, et al. The behavior change technique taxonomy (v1) of 93 hierarchically clustered techniques: building an international consensus for the reporting of behavior change interventions. Ann Behav Med. 2013; doi:10.1007/s12160-013-9486-6.

Michie S, Johnton M, Francis J, Hardeman W, Eccles M. From theory to intervention: mapping theoretically derived behavioural determinants to behaviour change techniques. Appl Psychol Int Rev. 2008; doi:10.1111/j.1464-0597.2008.00341.x4651858.CD008963.pub2.

Michie S, Atkins L, West R. The behaviour change wheel: a guide to designing interventions. United Kingdom: Silverback Publishing; 2015.

Hurley MV, Walsh NE, Mitchell H, Nicholas J, Patel A. Long-term outcomes and costs of an integrated rehabilitation program for chronic knee pain: a pragmatic, cluster randomized, controlled trial. Arthritis Care Res (Hoboken). 2012; doi:10.1002/acr.20642.

Patel G, Walsh N, Gooberman‐Hill R. Managing osteoarthritis in primary care: exploring healthcare professionals’ views on a multiple‐joint intervention designed to facilitate self‐management. Musculoskel Care. 2014; doi:10.1002/msc.1074.

Delitto A, George SZ, Van Dillen LR, Whitman JM, Sowa G, Shekelle P et al. Low back pain. J Orthop Sports Phys Ther. 2012; doi:10.2519/jospt.2012.0301.

Mansell G, Kamper SJ, Kent P. Why and how back pain interventions work: what can we do to find out? Best Pract Res Clin Rheumatol. 2013; doi:10.1016/j.berh.2013.10.001.

Miles CL, Pincus T, Carnes D, Homer KE, Taylor SJC, Bremner SA, et al. Can we identify how programmes aimed at promoting self-management in musculoskeletal pain work and who benefits? a systematic review of sub-group analysis within RCTs. Eur J Pain. 2011; doi:10.1016/j.ejpain.2011.01.016.

Wertli MM, Burgstaller JM, Weiser S, Steurer J, Kofmehl R, Held U. Influence of catastrophizing on treatment outcome in patients with nonspecific low back pain. Spine. 2014; doi:10.1097/BRS.0000000000000110.

Lee H, Hubscher M, Moseley GL, Kamper SJ, Traeger AC, Mansell G, et al. How does pain lead to disability? A systematic review and meta-analysis of mediation studies in people with back and neck pain. Pain. 2015; doi:10.1097/j.pain.0000000000000146.

Guerin S, Hennessy E. Pupils' definitions of bullying. Eur J Psychol Educ. 2002;17:249–61.

Peek K, Sanson-Fisher R, Mackenzie L, Carey M. Interventions to aid patient adherence to physiotherapist prescribed self-management strategies: a systematic review. Physiotherapy. 2015; doi:10.1016/j.physio.2015.10.003.

Hall AM, Kamper SJ, Hernon M, Hughes K, Kelly G, Lonsdale C, et al. Measurement tools for adherence to non-pharmacologic self-management treatment for chronic musculoskeletal conditions: a systematic review. Arch Phys Med Rehabil. 2015; doi:10.1016/j.apmr.2014.07.405.

Ryan RM, Deci EL. Self-determination theory and the facilitation of intrinsic motivation, social development, and well-being. Am Psychol. 2000; doi:10.1037/0003-066x.55.1.68.

Ng JYY, Ntoumanis N, Thogersen-Ntoumani C, Deci EL, Ryan RM, Duda JL, et al. Self-determination theory applied to health contexts: a meta-analysis. Perspect Psychol Sci. 2012; doi:10.1177/1745691612447309.

Delamater AM. Improving patient adherence. Clin Diabetes. 2006;24:71–7.

Hsu YT, Buckworth J, Focht BC, O'Connell AA. Feasibility of a self-determination theory-based exercise intervention promoting healthy at every size with sedentary overweight women: Project CHANGE. Psychol Sport Exerc. 2013;14:283–92.

Moustaka FC, Vlachopoulos SP, Kabitsis C, Theodorakis Y. Effects of an autonomy-supportive exercise instructing style on exercise motivation, psychological well-being, and exercise attendance in middle-age women. J Phys Act Health. 2012;9:138–50.

Silva MN, Vieira PN, Coutinho SR, Minderico CS, Matos MG, Sardinha LB, et al. Using self-determination theory to promote physical activity and weight control: a randomized controlled trial in women. J Behav Med. 2010; doi:10.1007/s10865-009-9239-y.

Silva MN, Marques MM, Teixeira PJ. Testing theory in practice: the example of self-determination theory-based interventions. Eur Health Psychol. 2014;16:171–80.

Knittle K, De Gucht V, Hurkmans E, Peeters A, Ronday K, Maes S, et al. Targeting motivation and self-regulation to increase physical activity among patients with rheumatoid arthritis: a randomised controlled trial. Clin Rheumatol. 2015; doi:10.1007/s10067-013-2425-x.

Williams GC, Grow VM, Freedman ZR, Ryan RM, Deci EL. Motivational predictors of weight loss and weight-loss maintenance. J Pers Soc Psychol. 1996;70:115–26.

Williams GC, Rodin GC, Ryan RM, Grolnick WS, Deci EL. Autonomous regulation and long-term medication adherence in adult outpatients. Health Psychol. 1998;17:269–76.

Williams GC, McGregor HA, Zeldman A, Freedman ZR, Deci EL. Testing a self-determination theory process model for promoting glycemic control through diabetes self-management. Health Psychol. 2004;23:58–66.

Lonsdale C, Hall AM, Williams GC, McDonough SM, Ntoumanis N, Murray A, et al. Communication style and exercise compliance in physiotherapy (CONNECT). A cluster randomized controlled trial to test a theory-based intervention to increase chronic low back pain patients' adherence to physiotherapists' recommendations: study rationale, design, and methods. BMC Musculoskel Dis. 2012; doi:10.1186/1471-2474-13-104.

Matthews J, Hall AM, Hernon M, Murray A, Jackson B, Taylor I, et al. A brief report on the development of a theoretically-grounded intervention to promote patient autonomy and self-management of physiotherapy patients: face validity and feasibility of implementation. BMC Health Serv Res. 2015; doi:10.1186/s12913-015-0921-1.

Murray A, Hall AM, Williams GC, McDonough SM, Ntoumanis N, Taylor IM, et al. Effect of a self-determination theory-based communication skills training program on physiotherapists' psychological support for their patients with chronic low back pain: a randomized controlled trial. Arch Phys Med Rehabil. 2015; doi:10.1016/j.apmr.2014.11.007.

Su Y, Reeve J. A meta-analysis of the effectiveness of intervention programs designed to support autonomy. Educ Psychol Rev. 2011;23:159–88.

Bowen DJ, Kreuter M, Spring B, Cofta-Woerpel L, Linnan L, Weiner D, et al. How we design feasibility studies. Am J Prev Med. 2009; doi:10.1016/j.amepre.2009.02.002.

Nolte S, Osborne RH. A systematic review of outcomes of chronic disease self-management interventions. Qual Life Res. 2013;22:1805–16.

Nolte S, Elsworth GR, Newman S, Osborne RH. Measurement issues in the evaluation of chronic disease self-management programs. Qual Life Res. 2013;22:1655–64.

Toomey E, Matthews J, Guerin S, Hurley DA. Development of a feasible implementation fidelity protocol within a complex physiotherapy-led self-management intervention. Phys Ther. 2016; Mar 3 [Epub ahead of print].

Yamato TP, Maher CG, Saragiotto BT, Moseley AM, Hoffmann TC, Elkins MR. The TIDieR checklist will benefit the physiotherapy profession. J Physiother. 2016; doi:10.1016/j.jphys.2016.02.015.

Du S, Yuan C, Xiao X, Chu J, Qiu Y, Qian H. Self-management programs for chronic musculoskeletal pain conditions: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Patient Educ Couns. 2011; doi:10.1016/j.pec.2011.02.021.

Oliveira VC, Ferreira PH, Maher CG, Pinto RZ, Refshauge KM, Ferreira ML. Effectiveness of self-management of low back pain: systematic review with meta-analysis. Arthritis Care Res (Hoboken). 2012; doi:10.1002/acr.21737.

Mansell G, Hill JC, Kamper SJ, Kent P, Main C, van der Windt DA. How can we design low back pain intervention studies to better explain the effects of treatment? Spine. 2014; doi:10.1097/BRS.0000000000000144.

Bandura A. Social foundations of thought and action: a social cognitive theory. New Jersey: Prentice-Hall; 1986.

Patrick H, Williams GC. Self-determination theory: its application to health behavior and complementarity with motivational interviewing. Int J Behav Nutr Phys Act. 2012; doi: 10.1186/1479-5868-9-18.

Halvari AEM, Halvari H, Bjornebekk G, Deci EL. Motivation and anxiety for dental treatment: testing a self-determination theory model of oral self-care behaviour and dental clinic attendance. Motiv Emot. 2010; doi:10.1007/s11031-010-9154-0.

Nolte S, Osborne RH. A systematic review of outcomes of chronic disease self-management interventions. Qual Life Res. 2013; doi:10.1007/s11136-012-0302-8.

French SD, Bennell KL, Nicolson PJ, Hodges PW, Dobson FL, Hinman RS. What do people with knee or hip osteoarthritis need to know? An international consensus list of essential statements for osteoarthritis. Arthritis Care Res (Hoboken). 2015; doi:10.1002/acr.22518.

Warburton DE, Nicol CW, Bredin SS. Health benefits of physical activity: the evidence. CMAJ. 2006;174:801–9.

Zhao G, Li C, Ford ES, Fulton JE, Carlson SA, Okoro CA, et al. Leisure-time aerobic physical activity, muscle-strengthening activity and mortality risks among US adults: the NHANES linked mortality study. Br J Sports Med. 2014; doi:10.1136/bjsports-2013-092731.

Callahan LF, Ambrose KR. Physical activity and osteoarthritis—considerations at the population and clinical level. Osteoarthritis Cartilage. 2015; doi:10.1016/j.joca.2014.09.027.

Lubar D, White PH, Callahan LF, Chang RW, Helmick CG, Lappin DR, et al. A national public health agenda for osteoarthritis 2010. Semin Arthritis Rheum. 2010; doi:10.1016/j.semarthrit.2010.02.002.

Hurley DA, Tully MA, Lonsdale C, Boreham CA, van Mechelen W, Daly L, et al. Supervised walking in comparison with fitness training for chronic back pain in physiotherapy: results of the SWIFT single-blinded randomized controlled trial (ISRCTN17592092). Pain. 2015; doi:10.1016/j.pain.0000000000000013.

Garber CE, Blissmer B, Deschenes MR, Franklin BA, Lamonte MJ, Lee IM,et al. American College of Sports Medicine position stand. Quantity and quality of exercise for developing and maintaining cardiorespiratory, musculoskeletal, and neuromotor fitness in apparently healthy adults: guidance for prescribing exercise. Med Sci Sports Exerc. 2011; doi:10.1249/MSS.0b013e318213fefb.

Bennell KL, Ahamed Y, Jull G, Bryant C, Hunt MA, Forbes AB, et al. Physical therapist-delivered pain coping skills training and exercise for knee osteoarthritis: randomized controlled trial. Arthritis Care Res (Hoboken). 2015; doi:10.1002/acr.22744.

Kahan BC, Diaz-Ordaz K, Homer K, Carnes D, Underwood M, Taylor SJ, et al. Coping with persistent pain, effectiveness research into self-management (COPERS): statistical analysis plan for a randomised controlled trial. Trials. 2014; doi:10.1186/1745-6215-15-59.

Toomey E, Currie-Murphy L, Matthews J, Hurley DA. Implementation fidelity of physiotherapist-delivered group education and exercise interventions to promote self-management in people with osteoarthritis and chronic low back pain: a rapid review part II. Man Ther. 2015; doi:10.1016/j.math.2014.10.012.

Oosterom-Calo R, Te Velde SJ, Stut W, Brug J. Development of motivate4change using the intervention mapping protocol: an interactive technology physical activity and medication adherence promotion program for hospitalized heart failure patients. JMIR Res Protoc. 2015; doi:10.2196/resprot.4282.

Sleddens EF, Kroeze W, Kohl LF, Bolten LM, Velema E, Kaspers P, et al. Correlates of dietary behavior in adults: an umbrella review. Nutr Rev. 2015; doi:10.1093/nutrit/nuv007.

Lakerveld J, van der Ploeg HP, Kroeze W, Ahrens W, Allais O, Andersen LF, et al. Towards the integration and development of a cross-European research network and infrastructure: the determinants of diet and physical activity (DEDIPAC) knowledge hub. Int J Behav Nutr Phys Act. 2014; doi:10.1186/s12966-014-0143-7.

Warsi A, Wang PS, LaValley MP, Avorn J, Solomon DH. Self-management education programs in chronic disease—a systematic review and methodological critique of the literature. Arch Intern Med. 2004;164:1641–9.

Chodosh J, Morton SC, Mojica W, Maglione M, Suttorp MJ, Hilton L, et al. Meta-analysis: chronic disease self-management programs for older adults. Ann Intern Med. 2005;143:427–38.

Devos-Comby L, Cronan T, Roesch SC. Do exercise and self-management interventions benefit patients with osteoarthritis of the knee? A meta-analytic review. J Rheumatol. 2006;33:744–56.

Walsh N, Mitchell H, Reeves B, Hurley M. Integrated exercise and self-management programmes in osteoarthritis of the hip and knee: a systematic review of effectiveness. Phys Ther Rev. 2006; doi:10.1179/108331906x163432

Zwar N, Harris M, Griffiths R, Roland M, Dennis S, Powell Davies G, et al. A systematic review of chronic disease management. Research Centre for Primary Health Care and Equity, School of Public Health and Community Medicine, University of New South Wales, Sydney. 2006. http://files.aphcri.anu.edu.au/research/final_25_zwar_pdf_85791.pdf. Accessed 15 April 2016.

Foster G, Taylor S, Eldridge S, Ramsay J, Griffiths CJ. Self-management education programmes by lay leaders for people with chronic conditions. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2007;4:CD005108.

Reid MC, Papaleontiou M, Ong A, Breckman R, Wethington E, Pillemer K. Self-management strategies to reduce pain and improve function among older adults in community settings: a review of the evidence. Pain Med. 2008;9:409–24.

Nunez DE, Keller C, Ananian CD. A review of the efficacy of the self-management model on health outcomes in community-residing older adults with arthritis. Worldviews Evid Based Nurs. 2009;6:130–48.

New Zealand Guidelines Group. RapidE: chronic care: a systematic review of the literature on health behaviour change for chronic care. Wellington: Ministry of Health; 2011.

Clark NM, Becker MH, Janz NK, Lorig K, Rakowski W, Anderson L. Self-management of chronic disease by older adults a review and questions for research. J Aging Health. 1991;3:3–27.

Lorig KR, Holman HR. Self-management education: history, definition, outcomes, and mechanisms. Ann Behav Med. 2003;26:1–7.

Barlow J, Wright C, Sheasby J, Turner A, Hainsworth J. Self-management approaches for people with chronic conditions: a review. Patient Educ Couns. 2002;48:177–87.

Clark NM. Management of chronic disease by patients. Annu Rev Publ Health. 2003;24:289–313.

Johnston S, Liddy C, Ives S, Soto E. Literature review on chronic disease self-management. The Champlain local health integration network; 2008.

Coster S, Norman I. Cochrane reviews of educational and self-management interventions to guide nursing practice: a review. Int J Nurs Stud. 2009;46:508–28.

May S. Self-management of chronic low back pain and osteoarthritis. Nat Rev Rheumatol. 2010;6:199–209.

Jang Y, Yoo H. Self-management programs based on the social cognitive theory for Koreans with chronic disease: a systematic review. Contemp Nurse. 2012;40:147–59.

Department of Health and Children. Health in Ireland Key Trends 2013 [Press release]. http://health.gov.ie/?s=key+trends+2013. Accessed 20 July 2014.

Smith J, Firth J. Qualitative data analysis: the framework approach. Nurse Res. 2011;18:52–62.

Pope C, Ziebland S, Mays N. Qualitative research in health care: analysing qualitative data. BMJ. 2000;320:114.

Butler DS, Moseley GL. Explain pain. 2nd ed. Adelaide: NOI Group Publications; 2013.

Roland M. The back book: the best way to deal with back pain: get back active. Norwich: The Stationery Office; 2002.

National Institute for Health and Care Excellence: PH44 - Physical activity: brief advice for adults in primary care. 2013. https://www.nice.org.uk/guidance/ph44. Accessed 10 June 2015.

Department of Health: UK Physical Activity Guidelines. 2011. https://www.gov.uk/government/publications/uk-physical-activity-guidelines. Accessed 10 June 2015.

National Institute for Health and Care Excellence: PH41—walking and cycling: local measures to promote walking and cycling as forms of travel or recreation. 2012. https://www.nice.org.uk/ph41. Accessed 10 June 2015.

National Institute for Health and Care Excellence: NG7—maintaining a healthy weight and preventing excess weight gain among adults and children. 2015. https://www.nice.org.uk/guidance/ng7. Accessed 10 June 2015.

National Institute for Health and Care Excellence: PH53—managing overweight and obesity in adults—lifestyle weight management services. 2014. https://www.nice.org.uk/guidance/ph53. Accessed 10 June 2015.

Acknowledgements

The authors wish to thank the patients and physiotherapists in the HSE primary community and continuing care services who gave their time and worked with us throughout this process, Dr Sarah Dean, Dr Lou Atkins and Alison Keogh who reviewed and provided feedback on the behaviour change technique content and William Fox for assistance with manuscript preparation.

The paper presents independent research funded by the Health Research Board in Ireland through the Health Research Awards 2012 Scheme (Grant No. HRA_HSR/2012/24). The views expressed in this paper are those of the author(s) and not necessarily the Health Research Board or the Health Services Executive.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Authors’ contributions

DAH conceived and designed the study, contributed to analysis and interpretation of all data and drafted and critically revised the manuscript. LCM contributed to the design, data collection, analysis and interpretation of the needs assessment and drafted an earlier version of the manuscript. DH analysed the focus group and manager interview data and helped to draft the manuscript. AMH contributed to the design of the study, the identification of the determinants of SM behaviour, outcomes, performance objective and change objectives and helped to critically revise the manuscript. ET contributed to the design, data collection and analysis of the patient interviews and helped to critically revise the manuscript. SMcD contributed to the design of the study and interpretation of data and helped to critically revise the manuscript. CL contributed to the design of the behaviour change process of the intervention and helped to critically revise the manuscript. NW contributed to the adaptation of the FASA intervention and helped to critically revise the manuscript. SG contributed to the design and data collection of the focus group, physiotherapist and patient interview studies and interpretation of the resultant data and helped to critically revise the manuscript. JM contributed to the design of the study and interpretation of all data and helped to draft and critically revise the manuscript. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Additional files

Additional file 1:

Interview guides for semi-structured interviews and focus groups. (DOCX 71 kb)

Additional file 3:

Primary care physiotherapy services resource capacity checklist results. (DOCX 18 kb)

Additional file 6:

Results of feasibility analysis - focus groups. (DOCX 26 kb)

Additional file 7:

Matrix of change objectives for self-management behaviour. (DOCX 19 kb)

Additional file 8:

Matrix of change objectives for adoption and implementation. (DOCX 18 kb)

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made. The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver (http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/) applies to the data made available in this article, unless otherwise stated.

About this article

Cite this article

Hurley, D.A., Murphy, L.C., Hayes, D. et al. Using intervention mapping to develop a theory-driven, group-based complex intervention to support self-management of osteoarthritis and low back pain (SOLAS). Implementation Sci 11, 56 (2015). https://doi.org/10.1186/s13012-016-0418-2

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s13012-016-0418-2