Abstract

Background

Outcome for mental health conditions is suboptimal, and care is fragmented. Evidence from controlled trials indicates that collaborative chronic care models (CCMs) can improve outcomes in a broad array of mental health conditions. US Department of Veterans Affairs leadership launched a nationwide initiative to establish multidisciplinary teams in general mental health clinics in all medical centers. As part of this effort, leadership partnered with implementation researchers to develop a program evaluation protocol to provide rigorous scientific data to address two implementation questions: (1) Can evidence-based CCMs be successfully implemented using existing staff in general mental health clinics supported by internal and external implementation facilitation? (2) What is the impact of CCM implementation efforts on patient health status and perceptions of care?

Methods/design

Health system operation leaders and researchers partnered in an iterative process to design a protocol that balances operational priorities, scientific rigor, and feasibility. Joint design decisions addressed identification of study sites, patient population of interest, intervention design, and outcome assessment and analysis. Nine sites have been enrolled in the intervention-implementation hybrid type III stepped-wedge design. Using balanced randomization, sites have been assigned to receive implementation support in one of three waves beginning at 4-month intervals, with support lasting 12 months. Implementation support consists of US Center for Disease Control’s Replicating Effective Programs strategy supplemented by external and internal implementation facilitation support and is compared to dissemination of materials plus technical assistance conference calls. Formative evaluation focuses on the recipients, context, innovation, and facilitation process. Summative evaluation combines quantitative and qualitative outcomes. Quantitative CCM fidelity measures (at the site level) plus health outcome measures (at the patient level; n = 765) are collected in a repeated measures design and analyzed with general linear modeling. Qualitative data from provider interviews at baseline and 1 year elaborate CCM fidelity data and provide insights into barriers and facilitators of implementation.

Discussion

Conducting a jointly designed, highly controlled protocol in the context of health system operational priorities increases the likelihood that time-sensitive questions of operational importance will be answered rigorously and that the outcomes will result in sustainable change in the health-care system.

Trial registration

NCT02543840 (https://www.clinicaltrials.gov/ct2/show/NCT02543840).

Similar content being viewed by others

Background

Collaborative chronic care models and mental health outcome

Mental health conditions affect 46.6 % of Americans during their lives and impact 26.6 % in any given year [1]. Outcome for mental health conditions is suboptimal, and care coordination is problematic, even in integrated health-care systems like the US Department of Veterans Affairs (VA) [2, 3]. Multicomponent care models that emphasize care coordination and evidence-based care have been shown to improve health outcomes for individuals across a variety of mental health conditions.

Specifically, collaborative chronic care models (CCMs) were initially articulated by Wagner and colleagues [4, 5] and elaborated as part of the Robert Wood Johnson Improving Chronic Illness Care initiative [6]. CCMs were initially developed for chronic medical illnesses, stimulated by the recognition that single-component interventions were insufficient to improve outcome in such conditions [4, 5]. CCMs consist of several or all of six components:

-

Work role redesign to support anticipatory, continuous care;

-

Patient self-management support;

-

Provider decision support through simplified practice guidelines and/or facilitated access to specialty consultation;

-

Use of clinical information systems for panel management and provider feedback;

-

Linkage to community resources; and

-

Health care leadership and organization support [4, 5, 7–9].

Examples of how CCM elements can be operationalized in practice are provided in Table 1.

Multiple randomized controlled trials have shown that CCMs improve outcomes for various chronic medical illnesses [7–9] and depression treated in primary care [10, 11]. CCM principles have informed patient-centered medical homes [12] as well as VA primary care-mental health integration efforts [13].

Additional work has extended CCM application to a variety of chronic mental health conditions treated in mental health clinics, with an evidence base for some complex conditions like bipolar disorder that is sufficient to warrant endorsement in national practice guidelines [14, 15] and listing on the SAMHSA National Registry of Evidence-Based Programs and Practices [16]. Overall, meta-analytic work indicates that CCMs have robust effects in a variety of mental health conditions and across both primary care and specialty care settings at no net cost [17, 18].

CCM implementation challenges and opportunities

However, innovations such as CCMs do not naturally diffuse into common practice, even in integrated health-care systems. For example, after highly successful randomized clinical trials of the CCM for bipolar disorder in two integrated health-care systems, despite designing the studies from the outset as effectiveness trials [19, 20], no participating site continued the model after the trial ended. Thus, not surprisingly, specific efforts are needed to move innovations into sustainable practice [21, 22].

The opportunity to implement CCMs on a system-wide, potentially sustainable basis developed when the VA Office of Mental Health Operations (OMHO) began a high priority effort to enhance care coordination in general mental health clinics by establishing multidisciplinary teams in every VA medical center. Beginning in 2013, this Behavioral Health Interdisciplinary Program (BHIP) initiative directed facilities to develop teams to provide continuous access to recovery-oriented, evidence-based treatment, emphasizing population-based care, consistent with the VA’s Handbook on Uniform Mental Health Services in Medical Centers and Clinics [23]. BHIP teams provide multidisciplinary care guided by a staffing model of 5–7 full-time equivalent staff caring for a panel of 1000 patients. Facilities are provided centralized guidance [24] to institute care processes that are consistent with broad BHIP principles, but they are given broad latitude to develop team practices based on local priorities, resources, and conditions. The advantage to this flexible approach is that individual facilities have latitude to respond to local conditions in pursuing national goals; however, the challenge is that while the overall goals are clear, there is no certainty that facilities will employ evidence-based care processes.

In 2014, OMHO leaders partnered with implementation researchers to review the evidence base for team-based mental health care, and in 2015, OMHO endorsed the CCM as the model to inform BHIP team formation. The partnership obtained funding through a national competitive program evaluation process sponsored by the VA Quality Enhancement Research Initiative (QUERI) [25] to conduct a randomized quality improvement program evaluation to investigate two overarching propositions: (a) BHIPs can demonstrate impact on patient health status by incorporating elements of the evidence-based CCM and (b) focused implementation support is needed to support local efforts to establish such teams.

The protocol responds to time-sensitive health system needs, with design elements collaboratively developed to balance operational priorities, scientific rigor, and real-world feasibility. This protocol is described in the next section, with further description of specific partnered design decisions found in the “Discussion” section.

Methods/design

Implementation models and evaluation proposals

We designed a hybrid type III implementation-effectiveness controlled program evaluation [26] in order to investigate both implementation and health outcomes in the context of implementing an innovation with established evidence. Notably, this project relies on existing facility staff rather than incorporating exogenous research-funded staff as has been typical in traditional randomized controlled trials.

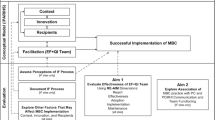

We chose an evidence-based implementation framework based on the US Center for Disease Control’s Replicating Effective Programs [27], augmented with internal and external implementation facilitation support [28] (called REP-F), which we have previously used jointly to implement the CCM in publicly funded health centers [29]. Analysis of the implementation effort is guided by the Integrated Promoting Action Research on Implementation in Health Services (i-PARIHS) framework, which proposes that successful implementation is a function of facilitation of an innovation with recipients who are supported and constrained within an inner and outer context [30].

We specifically hypothesize that, compared to technical assistance plus dissemination of CCM materials, REP-F-based implementation to establish CCM-based BHIPs will result in

H1a: increased veteran perceptions of CCM-based care,

H1b: higher rates of achieving national CCM fidelity measures, and

H1c: higher provider ratings of the presence of CCM elements (implementation outcomes), as well as

H2: improved veteran health status compared to BHIPs supported by dissemination material alone (intervention outcomes).

The overall model relating implementation strategy and CCM intervention to outcomes is diagrammed in Fig. 1.

Stepped-wedge trial design

To investigate these proposals, we utilize a stepped-wedge-controlled trial design. Stepped-wedge designs are randomized incomplete block designs which, though having a long history in scientific research [31, 32], have only recently been applied to controlled trials or program evaluations. Such designs provide the intervention of interest (REP-F in this protocol) to all participants, but stagger the timing of introduction [33–36]. The stepped-wedge design is increasingly used where all participants must receive the intervention for policy or ethical reasons [36] and has recently been used for CCM implementation in primary care [33]. In the current project, the stepped-wedge design confers two benefits: we can (a) extend implementation support to the maximal number of facilities and (b) enhance information from the formative evaluation of our implementation process.

We are utilizing a nested design, randomizing at the site level while using individual veterans as the unit of observation for primary quantitative outcome measures. Based on power calculations (see below), nine sites have been randomly assigned to receive REP-F support in one of three waves beginning at 4-month intervals, with REP-F support lasting 12 months (Fig. 2). The initial phase of REP-F implementation support lasts 6 months. In the second 6 months, the three sites that received REP-F gradually taper to step-down support (less frequent implementation meetings and consultation to the BHIP team on an as-needed basis). While waiting, sites will receive continued access to the extensive BHIP implementation materials on an internal VA website [24] and regular technical support conference calls, plus distribution of a workbook on incorporating CCM elements into existing BHIP teams.

This figure illustrates the stepped wedge for one of the three external facilitators, who will work with three facilities over the course of the study. Black dots represent times of health status assessment for patients. Provider interviews and administrative data measure collection occur at the beginning of implementation and at the end of the step-down period

Site selection and balance

Operations leaders asked in particular that we work with sites that have requested help to establish a BHIP team. We thus jointly developed these site inclusion criteria:

-

Self-identification of desire for assistance in developing a BHIP, as evidenced by invitation from the facility mental health service lead to concurrence of the facility director,

-

Prior identification of BHIP team members, and

-

Allocation of a staff member with quality improvement experience to serve as internal facilitator for 12 months at 10 % effort.

Facilities were recruited through a process involving cascading publicity from OMHO through the regional Veterans Integrated Service Networks (VISNs) to individual facility mental health service leaders.

Site-based randomization in any health-care system must face the reality that sites will never be completely matched on all relevant site characteristics, measured and unmeasured [37]. We therefore used a restricted selection method of randomization to balance key site characteristics across the three implementation waves [38]. We identified the following relevant site characteristics via OMHO-researcher consensus:

-

BHIP penetration rate, from national administrative measures;

-

Outpatient mental health service delivery characteristics, including average visits/year and telephonic vs. face-to-face care, from national administrative measures;

-

Prior success at the facility level with a mental health system redesign effort (penetration rate of primary care/mental health integration), from a national administrative measure;

-

Prior systems redesign experience for outpatient mental health staff, from a national provider survey;

-

Organizational climate with regard to civility and psychological safety in outpatient mental health, from a national provider survey;

-

Broader facility context including rurality and complexity rating, from national administrative measures; and

-

Administrative region (VISN).

We then utilized a computer-based algorithm to balance site characteristics as closely as possible [39, 40] across the three waves. After excluding highly collinear characteristics, the algorithm generated 1680 possible site combinations, and we randomly selected a grouping from 1 % of the best balanced options.

REP-F implementation procedures

REP-F implementation is deployed across the four REP stages: assessing preconditions, pre-implementation preparation, implementation, and post-implementation maintenance. REP-F is operationalized in this program via the following activities:

-

In-depth pre-site visit evaluation and orientation to the facilitation process and the CCM, including surveys and/or telephone-based interviews with facility leadership and mental health service leaders, internal facilitator, BHIP team members, and key stakeholders

-

Kick-off site visit of approximately 1.5 days

-

Weekly videoconferences with the BHIP team and/or conference calls with the internal facilitator as well as ad hoc telephone and email communications

-

Step-down support during the second 6 months of facilitation

Our pilot work led us to recognize the difference between facilitating to establish a single process or time-limited project and the need to build an ongoing team that can not only establish CCM processes but also adapt them sustainably as local conditions change. We therefore organized our efforts according to three overarching facilitation tasks (Fig. 3):

-

Team-building,

-

Identification of specific CCM goals and processes based on local conditions, and

-

Process change support.

As outlined in the text, this application of REP-F emphasizes the steps of team-building, identification of common goals based on local and national priorities, and process redesign as keys to eventual sustainment of system change. The steps are illustrated sequentially, but the process is iterative and nonlinear [41, 42]

Note, however, that these activities must be considered iterative and not strictly chronological, since implementation progress is likely to be nonlinear [41, 42]. Team-building is a critical step toward change and sustainability, as recognized by complex adaptive system approaches, but not necessarily present in more focused and time-limited QI efforts [41, 42]. Goal-identification is conducted in light of both national BHIP process measures and local priorities. Finally, to achieve those goals, specific process changes must be identified and implemented using traditional quality improvement techniques that empower the team to make ongoing iterative changes to their processes to best adapt as local conditions change, e.g., using plan-do-study-act cycles [43]. We incorporate CCM elements into identifying and changing processes, and this also feeds back on team-building as work roles are redesigned.

Formative evaluation of the implementation process

We plan our formative evaluation process according to the i-PARIHS update of the original PARIHS model [44], including four types of formative evaluation [45]: developmental, implementation-focused, progress-focused, and interpretive formative evaluation. Developmental formative evaluation will make use of extensive pre-site visit assessment materials, including pre-site visit key informant interviews, meeting with BHIP team members and relevant stakeholders, and review of the site-balancing characteristics enumerated above. Implementation-focused evaluation will focus on methods of operationalizing the CCM elements in a specific medical center. Progress-focused evaluation will make use of multiple sources of input to identify the barriers and facilitators to implementation progress, considering each of the i-PARIHS domains; these sources include regular review of progress toward specified clinical process changes, assessment of team strength, and regular debriefing among internal and external facilitators. Summative evaluation, as outlined in hypotheses 1 and 2, will include both qualitative and quantitative implementation outcomes as detailed below.

Summative quantitative evaluation (H1a, H1b, H2)

Subject-level measures will be collected in a repeated measures design via telephone interview, at the beginning of implementation and at 6 and 12 months of implementation. Primary quantitative health status outcomes include the Patient Assessment of Chronic Illness Care (PACIC) [46] (H1a), site- and veteran-level indices of BHIP clinical fidelity measures (H1b), and the veteran-level mental component score (MCS) and physical component score (PCS) of the VR-12 [47] (H2). The evaluation is quantitatively powered for H2, specifically the VR-12 MCS (90 % power, alpha = 0.05, effect size = 0.20 [18]). We will also collect patient satisfaction data using the Satisfaction Index [48] and the recovery-oriented Quality of Life Enjoyment and Satisfaction Questionnaire [49] as secondary measures. Note that the sample size accommodates “early looks” at the data at the end of each wave, in order to inform operational partners of emerging results in an operationally relevant time frame.

We are enrolling a survey sample of 85 veterans at each of nine sites (n = 765 total) who have had at least two treatment contacts over the prior year in a BHIP clinic. The sole exclusion criterion will be an encounter for dementia within the prior year, since their ability to complete the battery accurately would be questionable. We will gather administrative dataset-based demographic and clinical data on all BHIP veterans through our recruitment procedure and so can identify and adjust for sampling biases and systematic differences across sites and time points. For instance, we can investigate possible population changes over the course of the protocol, e.g., the possibility that as BHIP teams become established, their sicker (or healthier) veterans are referred.

Veteran- and site-level fidelity measures that reflect the CCM (H1b) are being developed nationally by OMHO. These will be collected from operationally gathered performance data. This provides the advantage that we can benchmark all participating sites against national performance rates, ensures relevance of trial outcomes to operational priorities, and decreases project resources for data collection.

Our analytic plan for H2 assesses veteran health status over time within subjects while minimizing respondent burden by using brief telephone interview at baseline and at 6 and 12 months of implementation. The primary evaluation compares the change from baseline to 12 months, the end of the implementation period (the implement and step-down periods in Fig. 1). Secondary evaluations will explore changes from baseline to 6 months and from 6 to 12 months to indicate if the effects tend to appear early or late in the 12-month period. The design allows evaluation of within-site changes in health status and quantitative process outcomes. Also, having staggered implementation but balancing site characteristics over time, we can assess the effects of secular trends at several calendar times with cross-sectional contrasts of a site undergoing implementation with a site awaiting implementation.

Our quantitative analyses will utilize repeated measures mixed effects general linear modeling (GLM) [50–52], with factors of intervention, site, time, and with subject within site as a random effects. GLM quantifies and apportions the variance in outcome (e.g., MCS) among relevant factors, thus isolating the change in outcome due to the primary contrast of interest (in this evaluation, REP-F implementation support vs. baseline). The mixed model accommodates repeated measures (within-subject correlation), random effects (subject), and moderate imbalance among independent factors (sites) and assumes that missing data are missing at random. We will explore results for patterns of unequal variance, relevant correlation structures, and variance component models to ensure that our results are robust. Additionally, the site sample sizes are large enough to explore various site-specific effects by adding site-interaction terms to the model.

Regarding missing data, we will test the robustness of results against nonrandom dropout patterns using Bayesian methods for the pattern mixture model [53, 54]. This systematically models the missing data using intensive Bayesian Monte Carlo Markov chain imputation to explore a wide range of potential non-missing mechanisms. These models for missing data dovetail with the proposed mixed model for the observed data allowing statistical tests of how explicit bias arising from nonrandom missingness alters the results of the primary analysis [54].

Additionally, secondary exploratory analyses will add covariates to determine the degree to which baseline factors explain the overall change. For instance, other independent variables include site characteristics and veteran characteristics such as demographics, mental health diagnoses, and history of mental health hospitalization.

A similar approach will be taken to analyze H1a, which proposes that veteran perceptions of CCM care, as measured by the PACIC, will be greater after REP-F implementation than at baseline. For H1b, we will also analyze those OMHO national BHIP process measures that are amenable to veteran-level measurement, comparing pre- to post-implementation status as above.

We will model response in a logistic regression model overall and by site to profile who responds and who does not using the covariates listed above as well as calendar time and status of implementation (pre or post). During the evaluation, we will also construct a propensity score for response with data from the entire general mental health clinic population at each medical center to predict future response and validate the primary analyses using propensity score weights as applied to clinical trials [55].

Summative qualitative evaluation (H1c)

Data from qualitative analyses will serve two purposes. First, directed content analysis [56] focusing on identification of CCM elements will provide data with which to assess fidelity to the intervention-dependent variable for H1c. Second, grounded thematic analysis [57] will contribute to interpretive formative evaluation [45] at the end of the evaluation, which could help explain unexpected implementation findings and refine facilitation steps to use in future efforts.

We will identify and consent four BHIP clinical staff per site, ensuring interdisciplinary representation across physicians, nurses, social workers, and psychologists. Interviews will be conducted via telephone, audio-recorded, and transcribed verbatim. There will be 72 total interviews: nine sites, four providers per site, and each interviewed pre- and post-implementation. Interviews will be de-identified, including information regarding the provider, site, and pre/post-implementation status of each interview.

We have oriented our qualitative analyses to complement our quantitative analyses, planning parallel data collection with integration post hoc [58]. For directed content analysis [56] to identify CCM elements, we will code data relevant to the presence or absence of each of the six CCM elements. Coded material will be summarized in narrative form (using principles of data reduction consistent with Miles and Huberman [57]). Based on coded data and summaries, each site’s fidelity to CCM elements will be rated on a scale of 0–4 to facilitate comparisons across sites and over time.

Our pilot work provided valuable methodologic data for our directed content analyses. We conducted semi-structured qualitative interviews with mental health providers at three medical centers with various levels of BHIP experience. We used an iterative procedure to develop a codebook for assessing the extent to which care at these three sites was consistent with each of the six CCM elements. Our codebook was organized according to the structure described by MacQueen and colleagues [59], featuring both brief and detailed definitions of each of the six CCM elements, as well as guidelines for when to apply (and not apply) each CCM element code, along with examples. We initially aimed to apply this codebook using rapid assessment [60] to identify individual quotes that were indicative of one or more CCM elements. We were unable to obtain adequate inter-rater reliability using this method, however, as we found that decontextualized quotes did not contain sufficient detail to identify CCM elements.

We therefore shifted to an approach in which interviews from each site were analyzed at the site level. We developed a separate site-level narrative that summarized care processes that were consistent (or not) with each of the six CCM elements. Whenever possible, this site narrative referred to specific quotes from the interviews but did not rely solely on such quotes taken out of the context of the individual interviews. We were able to quickly achieve consensus regarding site-level ratings using this method, distinguishing systematic differences among the three sites regarding consistency with CCM principles.

Formal statistical analyses of directed content analysis data are not appropriate [61]. However, our a priori proposal (H1c) is that for each site, CCM scores will increase from pre- to post-implementation, and we will be able to describe the degree to which this occurred within and across sites. Additionally, we will assess individual elements from provider’s ratings in each site to identify patterns of implementation across sites for individual CCM elements, which would add internal consistency validity to our conclusions; that is, common patterns would support (though not prove [56]) generalizability of implementation strategy effects.

For the interpretive formative evaluation [45], we will code interviews using our grounded thematic analysis [57] coding, paying particular attention to factors that might be barriers or facilitators to future implementation efforts [62]. These analyses will also be used to contextualize and explain our directed content analyses above.

Cost analysis

We will conduct a cost analysis based on time-motion assessments as in our previous work [63]. Specifically, we will choose random weeks to have external facilitators log all implementation-related activities during the first and second 6 months of implementation, including calls, emails, meetings, and product development. This, plus initial site visit time and travel cost, will provide a stable estimate of external facilitation expenses. For each site, we will also estimate the internal facilitator’s time in the same manner and estimate the time spent by clinical and support BHIP team members via scheduling analysis focusing on meetings related to team development (but not clinical activities). This will provide OMHO and facility leaders in the field with a reasonable estimate of the personnel and related costs of this implementation strategy.

Limitations and anticipated challenges

Despite utilizing pilot funding to make various design decisions in an evidence-based manner, several limitations warrant consideration. First, our clinical intervention is a multicomponent model, the CCM, rather than a single-process intervention. The complex adaptive systems [41, 42] perspective predicts that such a flexibly implemented multicomponent model will have greater success in improving health outcomes than focusing on a single process. While we have considered this carefully both conceptually and operationally, we recognize that the manner in which the six CCM elements will be deployed will be diverse across sites. We have developed a qualitative analysis strategy that will accommodate this diversity by allowing each element to be assessed individually, but in the context of CCM expectations, by directed content analysis. Moreover, we utilize a dual approach to maximize information yield from qualitative data, combining directed content analysis [59, 61] to identify CCM elements with grounded thematic analysis [57] to elucidate key facilitator and barriers to provide data to support OMHO’s plan for subsequent BHIP implementation.

Second, we have designed our quantitative veteran-level health status assessment as a within-subjects design, following individual veterans at three assessments over 12 months. We anticipate the need for replacement as veterans leave care or decline further participation. Based on our extensive experience with long-term clinical trial outcomes monitoring [19, 20], we have designed a very low-burden follow-up assessment procedure to minimize dropout, but plan to replace veterans who drop out and conduct sensitivity analyses to determine the degree to which conclusions are affected by including original participants with those who enter later.

Despite its advantages, the nested stepped-wedge design also has some limitations. As with any site-level intervention, subjects cannot be randomized to intervention or control condition nor can intervention precede nonintervention. Implementation in waves over time introduces possible time trends, and we cannot perfectly balance site characteristics over time, although our design allows us to identify such trends. Clustering and missing values that might produce dropout bias require us to make strong assumptions to analyze the data. These unavoidable issues call for the sensitivity analyses described above.

Finally, as with all hybrid designs, this work requires a multidisciplinary evaluation team. Additionally, the effort requires a multi-faceted project management plan that includes both parallel and serial tasks. The fact that this project is supported by both competitive grant funding and operations support means that each of the study tasks must be completed in the context of an evolving clinical and operational context. Success will require drawing on our diverse experience as operations experts, implementation scientists, clinical trialists, qualitative researchers, and managers of multi-site evaluation projects.

Trial status

This project includes both a quality improvement program evaluation component and a research component and has been approved as such by the VA Central Institutional Review Board. Specifically, the initiative to implement CCM-based BHIP is considered a quality improvement program evaluation project for which medical center leadership volunteers their facility, and individual consent of providers for this process is not obtained. In contrast, the participation of providers in the qualitative interviews is fully voluntary (and kept confidential from facility leadership) and considered research and therefore subject to informed consent. Similarly, veteran health status and care perception assessment are considered research, and informed consent is obtained. The investigators’ home sites are considered “engaged in research,” while the participating sites are not, since they are identifying the population of providers and veterans from which to recruit but are not themselves recruiting the subjects.

An advisory board has been constituted, including health system operational leaders, researchers, and a veteran representative. It has met regularly to design the protocol and will continue to meet to monitor study conduct and results.

Site recruitment using cascading publicity from OMHO to VISN mental health leads to facility mental health leadership was very successful, within 2 months exceeding the enrollment target of nine facilities. Nine sites have been formally enrolled with three additional sites which volunteered to receive facilitation support outside of the formal trial. At the time of this writing, the first wave of sites has been engaged in REP pre-implementation assessment.

Discussion

This project results from the collaborative work of health system operations partners and a multidisciplinary group of researchers, supported by competitive funding from the VA’s innovative QUERI program [25]. To review all the substantive discussions and decision-making processes that informed protocol design is precluded by space limitations. Nevertheless, the most salient or widely relevant discussions and design decisions are summarized in Table 2.

Several overarching themes in establishing partner-based evaluation projects [64, 65] can also be highlighted. First, it is the priorities of the operational partners that make this type of evaluation project possible. These include not only the relative importance of the initiative but also the tangible resources and limitations that impact the project. An example of this is also found in the DIAMOND project [66], which was made possible not only by a shared sense of importance of improving depression treatment in Minnesota but also by the removal of fiscal barriers to establishing CCM-based procedures in a fee-for-service system [67, 68].

Second, an appreciation by all partners for the distinct skillsets each brings to the implementation process is essential. Related to this, at the sustainability and spread stage, both groups of partners must carefully knit their perspectives together to form a cohesive, consistent message in producing materials to guide the field—all of which must be articulated with the audience of end-users in mind.

Third, there must be a realistic appreciation of the distinct business cases for the operational and academic success the partners work within. For operational partners, this often requires measurable impacts on performance over relatively short time frame, while for researchers, academic productivity is assessed in terms of publications and presentations over a longer time horizon. Overall, the level of collaboration must go beyond a nodding appreciation to a willingness to incorporate diverse perspectives into the products, in the service of the highest quality, most feasible, most relevant project attainable.

Abbreviations

- BHIP:

-

Behavioral Health Interdisciplinary Program

- CCM:

-

chronic care model

- GLM:

-

general linear model

- i-PARIHS:

-

Integrated Promoting Action Research on Implementation in Health Services

- MCS:

-

mental component score

- OMHO:

-

VA Office of Mental Health Operations

- PACIC:

-

Patient Assessment of Chronic Illness Care

- PCS:

-

physical component score

- QUERI:

-

VA Quality Enhancement Research Initiative

- REP-F:

-

Replicating Effective Programs

- VA:

-

Department of Veterans Affairs

- VISN:

-

Veterans Integrated Service Network

References

Kessler RC, Wang PS. The descriptive epidemiology of commonly occurring mental disorders in the United States. Ann Rev Public Health. 2008;29:115–29.

Hogan MF. New freedom commission report: the President’s new freedom commission: recommendations to transform mental health care in America. Psychiatr Serv. 2003;54:1467–74.

Watkins KE, Pincus HA, Paddock S, Smith B, Woodroffe A, Farmer C, et al. Care for veterans with mental and substance use disorders: good performance, but room to improve on many measures. Health Aff. 2011;30:2194–203.

Wagner EH, Austin BT, Von Korff M. Organizing care for patients with chronic illness. Milbank Q. 1996;74:511–44.

Von Korff M, Gruman J, Schaefer J, Curry SJ, Wagner EH. Collaborative management of chronic illness. Ann Intern Med. 1997;127:1097–102.

Chronic illness management. https://www.grouphealthresearch.org/our-research/research-areas/chronic-illness-management/. Accessed 9/25/2015.

Bodenheimer T, Wagner EH, Grumbach K. Improving primary care for patients with chronic illness: the chronic care model, part 1. JAMA. 2002;288:1775–9.

Bodenheimer T, Wagner EH, Grumbach K. Improving primary care for patients with chronic illness: the chronic care model, part 2. JAMA. 2002;288:1909–14.

Coleman K, Austin BT, Brach C, Wagner EH. Evidence on the chronic care model in the new millennium. Health Aff. 2009;28:75–85.

Badamgarav E, Weingarten SR, Henning JM, Knight K, Hasselblad V, Gano Jr A, et al. Effectiveness of disease management programs in depression. Am J Psychiatry. 2003;160:2080–90.

Gilbody S, Bower P, Fletcher J, Richards D, Sutton AJ. Collaborative care for depression: a cumulative meta-analysis and review of longer-term outcomes. Arch Intern Med. 2006;166:2314–21.

Croghan TW, Brown JD. Integrating mental health treatment into the patient centered medical home. Rockville (MD): Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality; 2010. AHRQ Publication No. 10-0084-EF.

Rubenstein LV, Chaney EF, Ober S, Felker B, Sherman SE, Lanto A, et al. Using evidence-based quality improvement methods for translating depression collaborative care research into practice. Fam Syst Health. 2010;28:91–113.

Yatham LN, Kennedy SH, O’Donovan C, Parikh SV, MacQueen G, McIntyre RS, et al. Canadian network for mood and anxiety treatments (CANMAT) guidelines for the management of patients with bipolar disorder: update 2007. Bipolar Disord. 2006;8:721–39.

Department of Veterans Affairs, Department of Defense. Clinical practice guidelines for management of bipolar disorder in adults, version 2.0. Washington (DC): Department of Veterans Affairs Office of Quality and Performance & US Army MEDCOM Quality Management Division; 2009.

USDHHS substance abuse and mental health administration national registry of evidence-based programs and practices (NREPP). http://www.nrepp.samhsa.gov/. Accessed 21 Aug 2014.

Woltmann E, Grogan-Kaylor A, Perron B, Georges H, Kilbourne AM, Bauer MS. Comparative effectiveness of collaborative chronic care models for mental health conditions across primary, specialty, and behavioral health settings: systematic review and meta-analysis. Am J Psychiatry. 2012;169:790–804.

Miller CJ, Grogan Kaylor A, Perron BP, Woltmann E, Kilbourne AM, Bauer MS. Collaborative chronic care models for mental health conditions: cumulative meta-analysis and meta-regression to guide future research and implementation. Med Care. 2013;51:922–30.

Bauer MS, McBride L, Williford WO, Glick HA, Kinosian B, Altshuler L, et al. Collaborative care for bipolar disorder: parts I&II. Intervention and implementation in a randomized effectiveness trial. Psychiatr Serv. 2006;57:927-36 & 937-45.

Simon GE, Ludman EJ, Bauer MS, Unützer J, Operskalski B. Long-term effectiveness and cost of a systematic care program for bipolar disorder. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2006;63:500–8.

Westfall JM, Mold J, Fagnan L. Practice-based research—“blue highways” on the NIH roadmap. JAMA. 2007;297:403–6.

Proctor EK, Landsverk J, Aarons G, Chambers D, Glisson C, Mittman B. Implementation research in mental health services: an emerging science with conceptual, methodological, and training challenges. Admin Policy Ment Health. 2009;36:24–34.

Veterans Health Administration. Uniform mental health services handbook. Washington (DC): The Administration; 2008.

BHIP technical assistance sharepoint. VA Office of Mental Health Operations, 2013. https://vaww.portal.va.gov/sites/OMHS/BHIP/default.aspx Accessed. 21 Aug 2014.

Stetler CB, Mittman BS, Francis J. Overview of the VA Quality Enhancement Research Initiative (QUERI) and QUERI theme articles: QUERI series. Implement Sci. 2008;3:8.

Curran GM, Bauer MS, Mittman BS, Pyne JM, Stetler CB. Effectiveness-implementation hybrid designs: combining elements of clinical effectiveness and implementation research to enhance public health impact. Med Care. 2012;50:217–26.

Neumann MS, Sogolow ED. Replicating effective programs: HIV/AIDS prevention technology transfer. AIDS Educ Prev. 2000;12 Suppl 5:35–48.

Kirchner JE, Ritchie MJ, Pitcock JA, Parker LE, Curran GM, Fortney JC. Outcomes of a partnered facilitation strategy to implement primary care-mental health. J Gen Intern Med. 2014;29 Suppl 4:904–12.

Kilbourne AM, Neumann MS, Pincus HA, Bauer MS, Stall R. Implementing evidence-based interventions in health care: application of the replicating effective programs framework. Implement Sci. 2007;2:42.

Harvey G, Kitson A. Implementing evidence-based practice in healthcare: a facilitation guide. London: Routledge; 2015.

Yates MA. Incomplete randomized blocks. Annals of Eugenics. 1936;7:121–40.

Fisher RA. An examination of the different possible solutions of a problem in incomplete blocks. Annals of Eugenics. 1940;10:52–75.

Parchman ML, Noel PH, Culler SD, Lanham HJ, Leykum LK, Romero RL, et al. A randomized trial of practice facilitation to improve the delivery of chronic illness care in primary care. Implement Sci. 2013;8:93.

Hussey MA, Hughes JP. Design and analysis of stepped wedge cluster randomized trials. Contemp Clin Trials. 2007;28:182–91.

Brown CA, Lilford RJ. The stepped wedge trial design: a systematic review. BMC Med Res Methodol. 2006. doi:10.1186/1471-2288-6-54.

King G, Gakidou E, Ravishankar N, Moore RT, Lakin J, Vargas M, et al. A “politically robust” experimental design for public policy evaluation, with application to the Mexican universal health insurance program. J Policy Anal and Manage. 2007;26:479–506.

Kazis LE, Miller DR, Skinner KM, Lee A, Ren XS, Clark JA, et al. Applications of methodologies of the Veterans Health Study in the VA health care system: conclusions and summary. J Ambul Care Manage. 2006;29:182–8.

Simon R. Restricted randomization designs in clinical trials. Biometrics. 1979;35:503–12.

Pocock SJ, Simon R. Sequential treatment assignment with balancing for prognostic factors in the controlled clinical trial. Biometrics. 1975;31:103–15.

Suresh KP. An overview of randomization techniques: an unbiased assessment of outcome in clinical research. J Hum Reprod Sci. 2011;4:8–11.

Jordan ME, Lanha HJ, Crabtree BF, Nutting PA, Miller WL, Stange KC, et al. The role of conversation in health care interventions: enabling sensemaking and learning. Implement Sci. 2009;4:15.

Plesk P. Redesigning health care with insights from the science of complex adaptive systems. In: Institute of Medicine. Crossing the Quality Chasm: A new health system for the 21st century. Washington, DC: National Academy Press; 2001. p. 309–22.

Varkey P, Reller M, Resar R. Basics of quality improvement in health care. Mayo Clinic Proc. 2007;82:735–9.

Stetler CB, Damschroder LJ, Helfrich CD, Hagedorn HJ. A guide for applying a revised version of the PARiHS framework for implementation. Implement Sci. 2011;6:99.

Stetler CB, Legro MW, Wallace CM, Bowman C, Guihan M, Hagedorn H, et al. The role of formative evaluation in implementation research and the QUERI experience. J Gen Intern Med. 2006;21 Suppl 2:s1–8.

Gugiu PC, Coryn C, Clark R, Kuehn A. Development and evaluation of the short version of the patient assessment of chronic illness care instrument. Chronic Illn. 2009;5:268–76.

Selim AJ, Rogers W, Fleishman JA, Qian SX, Fincke BG, Rothendler JA, et al. Updated http://www.queri.research.va.gov/ciprs/TDM_Module.pdf Qual Life Res. 2009;18:43-52.

Nabati L, Shea N, McBride L, Gavin C, Bauer MS. Adaptation of a simple patient satisfaction instrument to mental health: psychometric properties. Psychiatry Res. 1998;77:51–6.

Stevanovic D. Quality of Life Enjoyment and Satisfaction Questionnaire—short form for quality of life assessments in clinical practice: a psychometric study. J Psychiatr and Ment Health Nurs. 2011;18:744–50.

Diggle P, Heagerty P, Liang K-Y, Zeger S. Analysis of longitudinal data. 2nd ed. New York: Oxford Statistical Science; 2013.

Fitzmaurice G, Davidian M, Verbeke G, Molenberghs G, editors. Longitudinal data analysis. Boca Raton: Taylor & Francis; 2009.

Verbeke G, Molenberghs G. Linear mixed models for longitudinal data. New York: Springer; 2009.

Daniels MJ, Hogan W. Missing data in longitudinal studies. Boca Raton: Chapman & Hall; 2008.

Rybin D, Doros G, Rosenheck R, Lew RA. The impact of missing data on results of a schizophrenia study. Pharm Stat. 2015;14:4–10.

D’Agostino RB. Propensity score methods for bias reduction in the comparison of a treatment to a non-randomized control group. Stat Med. 1998;17:2265–81.

Hsieh HF, Shannon SE. Three approaches to qualitative content analysis. Qual Health Res. 2005;15:1277–88.

Miles MB, Huberman AM. Qualitative data analysis: an expanded sourcebook. Thousand Oaks: Sage; 1994.

Fetters MD, Curry LA, Creswell JW. Achieving integration in mixed methods designs-principles and practices. Health Serv Res. 2013;48:2134–56.

MacQueen KM, McLellan E, Kay K, et al. Codebook development for team-based qualitative analysis. Cultural Anthropology Methods. 1998;10:31–6.

Utarini A, Winkvist A, Pelto GH. Appraising studies in health using rapid assessment procedures (RAP): eleven critical criteria. Hum Organ. 2001;60:390–400.

Maguire E, Elwy AR, Bokhour BG, Gifford AL, Asch SM, Wagner TH, et al. Communicating large scale adverse events: lessons from media reactions to risk. Providence, RI: American Academy on Communication in Healthcare Forum; 2012.

Powell BJ, McMillen JC, Proctor EK, Carpenter CR, Griffey RT, Bunger AC, et al. A compilation of strategies for implementing clinical innovations in health and mental health. Med Care Res Rev. 2012;69:123–57.

Glick HA, Kinosian B, McBride L, Williford WO, Bauer MS. Clinical nurse specialist care managers’ time commitments in a disease management program for bipolar disorder. Bipolar Disord. 2004;6:452–9.

Charns MP, Egede LE, Rumsfeld JS, McGlynn GC, Yano EM. Advancing partnered research in the VA healthcare system: the pursuit of increased research engagement, responsiveness, and impact. J Gen Intern Med. 2014;29 Suppl 4:s811–3.

Selby JV, Slutsky JR. Practicing partnered research. J Gen Intern Med. 2014;29 Suppl 4:s814–6.

Solberg LI, Crain AL, Jaeckels N, Ohnsorg KA, Margolis KL, Beck A, et al. The DIAMOND initiative: implementing collaborative care for depression in 75 primary care clinics. Implement Sci. 2013;8:135.

Wolff JL, Boult C. Moving beyond round pegs and square holes: restructuring Medicare to improve chronic care. Ann Intern Med. 2005;143:439–45.

Bao Y, Casalino LP, Ettner SL, Bruce ML, Solberg LI, Unutzer J. Designing payment for collaborative care for depression in primary care. Health Serv Res. 2011;46:1436–51.

Bauer MS, Williford WO, Dawson EE, Akiskal HS, Altshuler L, Fye C, et al. Principles of effectiveness trials and their implementation in VA Cooperative Study #430: ‘reducing the efficacy-effectiveness gap in bipolar disorder’. J Affect Dis. 2001;67:61–78.

Acknowledgements

This work is supported by grants from the Department of Veterans Affairs Quality Enhancement Research Initiative (QUERI), #RRP-13-237 and QUE-15-289. The authors wish to gratefully acknowledge the assistance of Ms. Allyson Gittens in preparing this manuscript.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

Competing interests

MSB receives royalties from Springer Publishing and New Harbinger Publishing for publication of manuals related to the collaborative chronic care model.

Authors’ contributions

All authors contributed to the design of the protocol and the writing of the manuscript. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made. The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver (http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/) applies to the data made available in this article, unless otherwise stated.

About this article

Cite this article

Bauer, M.S., Miller, C., Kim, B. et al. Partnering with health system operations leadership to develop a controlled implementation trial. Implementation Sci 11, 22 (2015). https://doi.org/10.1186/s13012-016-0385-7

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s13012-016-0385-7