Abstract

Background

Evidence-based treatments (EBTs) are available for treating childhood behavioral health challenges. Despite EBTs’ potential to help children and families, they have primarily remained in university settings. Little empirical evidence exists regarding how specific, commonly used training and quality control models are effective in changing practice, achieving full implementation, and supporting positive client outcomes.

Methods/design

This study (NIMH RO1 MH095750; ClinicalTrials.gov Identifier: NCT02543359), which is currently in progress, will evaluate the effectiveness of three training models (Learning Collaborative (LC), Cascading Model (CM), and Distance Education (DE)) to implement a well-established EBT , Parent-Child Interaction Therapy, in real-world, community settings. The three models differ in their costs, skill training, quality control methods, and capacity to address broader implementation challenges. The project is guided by three specific aims: (1) to build knowledge about training outcomes, (2) to build knowledge about implementation outcomes, and (3) to test the differential impact of training clinicians using LC, CM, and DE models on key client outcomes. Fifty (50) licensed psychiatric clinics across Pennsylvania were randomized to one of the three training conditions: (1) LC, (2) CM, or (3) DE. The impact of training on practice skills (clinician level) and implementation/sustainment outcomes (clinic level) are being evaluated at four timepoints coinciding with the training schedule: baseline, 6 (mid), 12 (post), and 24 months (1 year follow-up). Immediately after training begins, parent–child dyads (client level) are recruited from the caseloads of participating clinicians. Client outcomes are being assessed at four timepoints (pre-treatment, 1, 6, and 12 months after the pre-treatment).

Discussion

This proposal builds on an ongoing initiative to implement an EBT statewide. A team of diverse stakeholders including state policy makers, payers, consumers, service providers, and academics from different, but complementary areas (e.g., public health, social work, psychiatry), has been assembled to guide the research plan by incorporating input from multidimensional perspective.

Trial registration

ClinicalTrials.gov: NCT02543359

Similar content being viewed by others

Background

Disruptive behavior disorders (DBDs) affect a substantial number of young children, have lifelong implications if left untreated (e.g., [1–7]), and represent the most common presenting problem to community mental health centers [8, 9]. Meta-analytic reviews of treatment outcomes for DBDs (e.g., [10]) demonstrate that there are EBTs for DBDs. Parent–Child Interaction Therapy (PCIT) is a nationally recognized EBT for families who have children with DBDs [11]. The program is unique in comparison to other EBTs for DBDs in that it involves coaching parents as they interact with their young child (ages 2.5 –7 years). For each of two treatment phases, parents attend one didactic parent-only session during which the PCIT therapist teaches parents specific skills that will be “coached” in vivo in subsequent sessions. Parents attend approximately 12–20 weekly, 1-hour clinic-based sessions with their child [12].

Treatment outcome data from multiple randomized trials indicate that PCIT decreases child behavior problems, increases parent skill, and decreases parent stress [12–14]. When compared to waitlist controls, treatment effect sizes for PCIT range from 0.61 to 1.45 (absolute values) for parent report of child behavior and 0.76 to 5.67 for behavior observations of parent skill improvements [14]. Behavior observations indicate pre-post changes in parent behavior such as increased rates of praise, descriptions, reflections, and physical proximity and decreased rates of criticism and sarcasm (e.g., [15]). Parents report lower parenting stress, more internal (rather than external) locus of control, and increased confidence in parenting skills after learning PCIT. Parents report that child behavior improves from the clinical range to within normal limits on multiple, standardized parent report measures [15–17]. Studies have been conducted to understand the maintenance of treatment benefits [18–21], finding the majority of children (69 %) maintained gains on measures of child behavior and activity level, and over half (54 %) remained free of DBD diagnoses at 2 years post-treatment) [19].

The majority of PCIT treatment outcome studies have been efficacy trials. However, a number of effectiveness studies have also been conducted and demonstrated the positive impact of PCIT on parent, child, and family outcomes for families who complete treatment (e.g., [22, 23, 24 ]). These initial PCIT effectiveness studies also highlight some concerns when providing PCIT in community-based settings, such as higher rates of treatment attrition compared to efficacy trials.

Despite EBTs’ potential to help children and families, EBTs have primarily remained in university settings, with several reports (e.g., [25, 26]) highlighting a lack of access to EBTs in community settings. EBTs seem to be valued in frontline practice, and there is a strong push to implement them; however, the field seems to not know how best to do it, especially at scale. Billions of dollars have been invested in developing EBT implementation initiatives, yet EBTs have yet to reach their intended populations. Perhaps this is related to the lack of empirical attention devoted to training models for EBTs [27]. Little empirical attention has been paid to those who provide community care and how to effectively train them [28]. A comprehensive, recent review [28] found that three training models that are increasingly commonly used are Learning Collaborative (LC), Cascading Model (CM), and Distance Education (DE).

With the support of substantial federal funds (i.e., budgets of $29 (FY07) and $33 million (FY08)), The National Child Traumatic Stress Network (NCTSN) has focused on the implementation of EBTs [27] via the LC model. The LC approach was modeled after the Institute for Healthcare Improvement’s Breakthrough Series Collaborative Model [29, 30] for use in mental health [31]. LCs target and include multiple levels within an organization (clinicians, supervisors, senior leaders) by structuring information for specific roles. LCs can involve episodic meetings to share implementation tactics, plans, and evaluation results across multiple organizations involving several staff from each. The LC model has been implemented within healthcare for a variety of purposes (e.g., [32–36]). Within mental health, the NCTSN has used the LC method for a decade to implement several EBTs across the USA; however, there is only one published study on these efforts [37]. Four studies have been published on the use of a LC to improve engagement in mental health services [38–41] which provide primary support for initiating [38] and sustaining [39] gains in initial appointment show rates. Only one randomized controlled trial (RCT) has been completed with LCs [42], which did not find favorable results (the remaining used pre-post designs). When 44 primary care clinics were randomized to either a LC or control condition, there were few statistically and no clinically significant differences in preventive service delivery rates [42]. LCs likely are costly to implement because of the staff and coordination time required.

Cascading training models (also commonly called train-the-trainer models) have the potential to be time- and cost-effective and are widely used in mental health [43, 44], addictions [45, 46], medicine [47–53], and prevention [54–60]; however, this method has received little rigorous examination. The CM involves an EBT expert providing extensive clinical training to a community-based clinician who in turn replicates that clinical training with other clinicians within her organization. Within mental health, three early studies, two single subjects [61, 62], and one [63] quasi-experimental design, indicate a “watering down” effect from supervisors to staff [62]. In the only published RCT including CM (compared to expert and self-study) few differences were found between CM and expert training on fidelity or competence in rated client sessions. In role-played sessions, participants in the expert training condition evidenced greater gains initially; by 12-week follow-up, there were no differences across conditions in client or role-play sessions [46]. Train-the-trainer models may rely heavily on the individual trainer, making them vulnerable to that person’s turnover or change of role. The trainer may serve as a local champion for the model, potentially troubleshooting the implementations of organizational needs but not to the degree inherent in the LC structure.

DE, with strategies that include an individual’s attempt to acquire information or skills by independently interacting with training materials (e.g., computer, videotape review; not simply reading materials), are a common way clinicians learn new treatments [64], have been rated favorably by learners [65] and found to be a cost-effective method to increase knowledge [66, 67]. However, when stringent assessment methods are used, DE has been found to work only for some therapists (e.g., [68]) and to be only slightly more effective than reading written materials at improving knowledge [66, 69]. Of note, when more sophisticated online training methods are used, DE has shown favorable effects as compared to written materials or workshop training with regard to increased knowledge, competence, and fidelity. Sophisticated DE methods have the advantage of being cost-effective and the potential to make a broader public health impact given that more clinicians could access an online system than could attend in-person training. However, they may be less able to address implementation challenges beyond practitioner skill training, which LCs specifically and directly address and which CM models may indirectly address via a local trainer as EBT champion within an organization. In sum, each of these models has a distinct balance of potential strengths and limitations across dimensions of cost, effort, organizational impact, resilience to turnover, and sustainment.

Methods/design

Within implementation science most conceptual frameworks acknowledge that implementation is a complex, interactive process in which clinician behavior (clinical practice) is influenced by individual and environmental characteristics as well as the quality of the intervention and the training design [70]. In this application (ClinicalTrials.gov Identifier: NCT02543359), we borrow from two frameworks: (1) the training transfer conceptual model [71] and (2) draft model of implementation research [72]. These frameworks were chosen because of their focus on training and transfer rather than broader competing frameworks.

Originally proposed by Baldwin and Ford [73], Ford and Weissbein [71] updated a conceptual model, the Training Transfer Conceptual Model, that was developed from an industrial/organizational psychology research review to articulate the conditions (training inputs) that impact training outcomes and training transfer (implementation). While the studies reviewed in these articles were not therapist/therapy studies, the conceptualization remains relevant. The review confirmed three types of training input factors that impact learning, retention, generalization, and maintenance of skills: trainee characteristics, training design, and work environment. In this study, the experimental manipulation has been at the Training Design level. The outputs of learning and retention are operationalized to include knowledge, skills, and attitude [74]. Transfer conditions include generalization and maintenance, which in this case, would include how clinicians apply the EBT in their setting and with families they treat (i.e., implementation and client outcomes).

Proctor and colleagues [72] have proposed a heuristic model that accounts for intervention strategies (EBT), implementation strategies (i.e., training models), and three distinct but interrelated set of outcomes within implementation research: implementation, service, and client outcomes. Using this taxonomy, we will use one intervention strategy (PCIT) to test three different training designs (LC, CM, DE) and will measure implementation and client outcomes to understand the conditions of transfer (generalization and maintenance). To understand the effectiveness of training methods, we will also measure training outcomes (outputs) articulated by Ford and Weissbein [71]. Measuring both implementation and client outcomes will help us to understand the success of the training condition for implementing an EBT in community settings [75]. Training outcomes (clinician level) are assessed using observational and self-report methods at four timepoints coinciding with the training schedule: baseline, 6 (mid), 12 (post), and 24 months (1 year follow-up). Immediately after clinician training began, parent–child dyads are recruited from the caseloads of participating clinicians. Client outcomes (parent–child dyad level) are assessed by parent report at four timepoints (pre-treatment, 1, 6, and 12 months after the pre-treatment). Implementation outcomes [75] (clinic level) are assessed using behavior observation, interview, and self-report measures with administrators, clinicians, and families at baseline, 6 (mid), 12 (post), and 24 months (1 year follow-up). This will include examining the overall penetration of the EBT (e.g., how extensively it is used) and whether the EBT is able to be diffused through the organization and sustained over the course of the study.

Participants and enrollment procedures

Clinics

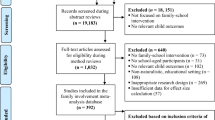

Highlighted in Fig. 1 (clinical enrollment flowchart), there are 508 licensed, psychiatric outpatient clinics across Pennsylvania. Given concerns about contamination across study condition, if one organization operated in multiple counties (e.g., an organization had outpatient clinics in neighboring counties), the organization was only able to participate in one county. This eliminated 201 clinics from inclusion. We excluded clinics that did not treat young children (eliminating 73 clinics), had previously participated in PCIT training (eliminating 33 clinics), and had a restricted service population (e.g., specialized in treating developmental disabilities or trauma; eliminating 34 clinics).

Because we randomized at the county level, we had to approach county administrators before clinic administrators. All 67 counties were approached; 40 agreed to informational meetings. Because 27 counties did not agree to informational meetings, 73 clinics were not given the opportunity to participate. Of the remaining 94 clinics eligible for participation, 50 agreed to participate. With the support of the state children’s mental health office, we gathered data on the clinics that were not interested in participating to understand potential selection bias (e.g., clinic size, population treated, county).

To be enrolled, clinics also met the following criteria: (a) willing to participate in PCIT training, (b) able to cover site preparation costs, and (c) agreeable to research participation.

Administrators

To be eligible, administrators were employed at a clinic selected to participate in training as an Executive Director, Chief Financial Officer, or other person responsible for daily operations.

Clinicians

To be eligible, clinicians were (a) currently employed at a clinic selected to participate in training, (b) a masters or doctoral level professional in the human services field (e.g., social work, psychology, education), (c) licensed in his/her field OR receiving supervision from a licensed individual, (d) actively seeing children and families who are appropriate for PCIT (e.g., age, behavior problem severity), (e) receptive to training but not previously trained in PCIT, and (f) amenable to study tasks (e.g., video taping, completing assessments).

Based on experience with implementation studies [76, 77] and high mental health workforce turnover [78, 79], we anticipated that few clinicians will leave the training or withdraw from the study (e.g., we had a retention rate of 96 % (187/195) for clinicians in a similar trial). However, we anticipate that up to 35 % of clinicians will leave their clinics (e.g., resign) or change jobs within their clinic during the course of the study [77]. Using an intent-to-train model, clinicians who leave their clinic will remain in the study, but we may lose some clinic and client level data unless the clinician goes to another clinic that is already participating in the study or providing PCIT. All efforts have been made to get full data, but clinic level ethical, fiscal, and logistical details (e.g., FWAs, IRB protocols) may prohibit full data collection at a new site.

Parent–child dyads

Clinicians were asked to refer all families on their caseload with whom they are using PCIT. Inclusion criteria include any parent–child dyad who the clinician enrolled in PCIT services. A child is excluded only if he/she is a ward of the state or living in state custody. Under the study state’s law, only the birth parent or a guardian with parental rights can provide informed consent.

Clinicians ask each parent participating in PCIT to sign a “permission to contact form.” Clinicians fax the form to the research team. A research assistant contacts the parent to confirm eligibility, review informed consent including permission to video tape, and complete the first of four assessments. Subsequent assessments are completed via phone, paper, or online (depending on parent preference).

We anticipate an 88 % retention rate based on experience in previous trials; a minimum of 253 parent–child dyads likely will complete all four assessments. We estimate that the clinician to enrolled family ratio will be approximately 1:1 though we will try to improve that ratio. In previous trials, we had estimated a 1:2 ratio; however, given clinician turnover and other challenges, 1:1 has been a more accurate estimate for recent child-focused, community-based trials [80, 81].

To enhance participant recruitment and retention, incentives have been included at each level: (1) clinics receive free training for their clinicians as well as either a small stipend ($1000) to offset initial PCIT start-up costs (e.g., bug-in-the-ear) or a PCIT package including equipment (e.g., video cameras) necessary for the research and helpful for treatment; (2) administrators receive payment for assessment completion; (3) clinicians receive free training, Continuing Education Credits, and payment for time invested in assessment completion (not training); and (4) parent–child dyads receive payment for assessment completion. Top officials from several state offices and behavioral health managed care companies in Pennsylvania have endorsed and are substantively involved in this research, which also may positively impact participation.

Contact and monitoring procedures

Due to data collection occurring across levels of participants at multiple timepoints, we have implemented a variety of prompting and monitoring procedures to enhance participation. Specifically, participants are provided with choices related to the method of data collection (paper, online, or phone) as well as preferred contact method. The study team has utilized email, phone, postal mail, and text messaging to communicate with participants.

Procedures

Randomization

Counties with at least one participating clinic located in the county were randomized to study condition [82]. Randomization occurred at the county level for two reasons. First, the state in which the study is being conducted is a commonwealth that is “state administered and county controlled” meaning that there is considerable variability in how counties implement mental health policies. Given that this project, like any EBT implementation, will require clinics to develop new programs and possibly rely on the larger system/context of which they are a part of, there could be substantial variability for implementation across counties. For example, establishing a referral base likely will impact implementation outcomes and will be different across counties. Given that this variability would be difficult to quantify, our goal has been to balance across conditions through the randomization procedure. Second, it is not logistically or financially possible to train all clinics at once. If we were to randomize clinics to a condition it is probable that within one county, we would have multiple training conditions occurring at different times. This could affect the previous training condition, particularly for smaller counties where clinics might have close communication or even share clinicians. Similar to previous trials that have randomized at the county level [82, 83], randomization of county to condition was balanced on key covariates including population size (urban/ rural) and poverty level [84].

Training occurred through four waves because it would be impossible to train all clinics at the same time. Given these constraints, we used SAS to write a routine for the randomization. Within training wave 1, counties were randomized to one of two conditions. Within waves 2, 3, and 4, counties were randomized to one of three conditions. The two conditions implemented in wave 1 were randomly chosen from the three conditions. The reason for this change was because wave 1 occurred early in the study when recruitment was beginning, and fewer counties had agreed to participate by study deadlines. Wave 1 included 5 clinics located in 2 counties. Wave 2 included 18 clinics located in 12 counties. Wave 3 included 13 clinics located in 4 counties. Wave 4 included 14 clinics located in 12 counties.

Training conditions

The experimental manipulation in this study was within the Training Design of the Training Transfer Conceptual Model [71]. Table 1 highlights key similarities and differences across groups. Trainers were balanced across conditions. Consistent across each training condition was treatment content (i.e., treatment manual, coding manual, and workbook) and consultation with a trainer.

Learning collaborative

Consistent with the Institute for Healthcare Improvement [29] and NCTSN [31] protocols, the LC involved three phases: collaborative pre-work, learning sessions, and action periods. Pre-work activities were conducted prior to a face-to-face meeting to ensure that all participants come to the learning session with similar levels of PCIT knowledge. The pre-work “launch phase” (3 months) included readings, material review, and conference calls. Learning sessions included three 2-day, face-to-face meetings over a period of 9 months. Action periods occurred between learning sessions and were characterized by plan-do-study-act cycles, use of improvement data, use of technology to support learning, team meetings, and conference calls. Four people per clinic participated in the LC as part of a “core team,” including an administrator, supervisor, and two clinicians. Each LC included multiple clinic teams, was organized by a coordinator, and supported by faculty experts in PCIT and program development (e.g., financing, marketing, encouraging referrals, mobilizing clinic support). Components that make this training condition unique include the following: (1) addressing multiple organizational levels; (2) organizing “core teams”; (3) emphasizing collaborative, cross-site sharing; and (4) utilizing a quality improvement process focused on collecting implementation targets/data. After 1 year of intensive training, agencies selected one supervisor and one clinician to participate in additional training focused on training others within their organization. The inclusion of within-organization training in the LC is consistent with the intention of the training model to embed local expertise and promote sustainability. Those clinicians not involved in within-organization training continued phone consultation with the trainer at a reduced frequency (once per month) over a 6-month period (months 12 through 18 of training).

Cascading model

Consistent with the protocol recommended by the PCIT International Training Committee [85], this condition consisted of 40 hours of initial face-to-face contact with a PCIT trainer, an advanced live training (16 hours ) with real cases 6 months after the initial training, and bi-weekly contact with a trainer conducted over 12 months. After the end of the 12-month intensive training, trainees participated in 6 months of ongoing consultation and training, to begin training others within their organization. Each CM training group included 8 to 12 participants (two clinicians from each organization). Components that make CM unique include the following: (1) a “top-down,” hierarchical training approach; (2) strong and specific focus on two advanced clinicians; (3) extensive use of in vivo skill modeling, direct practice, observation, and feedback within the clinic setting; and (4) capacity for clinicians to return to organization as “in-house” or “within-organization” trainers to replicate clinical training with other clinicians within the organization. CM also focuses on trainers reviewing clinicians' videetaped sessions and providing them with feedback on treatment fidelity and competence. The clinicians trained by “in-house” trainers are also included in the study so that we can understand the impact of a cascading training.

Distance education (DE)

An online training similar to TF-CBT Web [86] was developed by the University of California, Davis Medical Center PCIT Team (SAMHSA grant; PI: Urquiza) and used in this study as part of the DE condition. The online training consisted of 11 modules/training topics, took clinicians approximately 10 hours to complete and included written materials, vignettes, videos, and quizzes for each topic. In this DE condition, the website was augmented for each participant with copies of the PCIT Treatment manual, Dyadic Parent–Child interaction Coding System (DPICS) Manual, and DPICS Workbook. Clinicians also participated in phone consultation with a trainer consistent with other training conditions.

Outcome measures and assessment procedures

The three primary outcomes of interest are training, implementation, and client outcomes. A review of outcomes measures across participants and timepoints is provided in Table 2.

Aim 1: determine the effects of training condition (CM, LC, DE) on training outputs (i.e., clinician knowledge, skill, and attitude)

Analyses

We hypothesize that the greatest improvements will be found for clinicians in the CM group followed by LC, clinic staff trained by clinicians in CM and LC groups, and DE (in that order). We will use the change scores on the following Ford-Weissbein [71] training outcomes: Coaches Quiz, Competence Check, and Coach Coding. Because training is at the clinician level, we will compute the change scores for each clinician and then compare the treatments using those changes. We recognize that the clinicians are nested within organization and will include that in our regression model, along with any other covariates that are associated with outcomes. We will use the one-way analysis of variance (ANOVA) to compare the change scores between the four groups. And because we have stated an ordered alternative (e.g., CM better than LC), we will use Bartholomew’s test which is powered for ordered alternatives unlike the usual F test, which is an omnibus test. Later, we will test the cascading effect of the CM model in comparing the performance of "second generation" CM clinicians to other clinicians in other conditions (CM-generation one, DE, LC).

Aim 2: explore implementation outcomes, including acceptability, adoption, appropriateness, feasibility, fidelity, penetration, sustainability, and cost across training conditions

Analyses

Using the taxonomy of implementation outcomes defined by Proctor et al. [87], data will be collected on acceptability, adoption, appropriateness, feasibility, fidelity, penetration, and sustainability. We have four main hypotheses related to implementation outcomes. First, we hypothesize that rates of acceptability and appropriateness of PCIT will be high and equal across groups. Without doing a formal hypothesis test, we will examine the rates of acceptability and appropriateness. Second, we hypothesize that rates of adoption, fidelity, and feasibility will be the highest among the more active training conditions (LC, CM). As in Aim 1, we will compare these measures using a one-way ANOVA, with Bartholomew’s test for the ordered alternative. Third, we hypothesize that implementation costs will be lowest for the DE and highest for LC. We will compare the costs per clinician for the various treatments using ANOVA comparing the three once again. Measurement and analysis of cost will be supported by a consulting health economist. Finally, we hypothesize that participants in the LC will evidence greater penetration and sustainability of PCIT within the service settings. Because penetration is a proportion, we will first stabilize variances using the arcsin transform; we will then use one-way ANOVA as in Aim 1.

Aim 3: evaluate improvement for parent–child dyads treated by clinicians across training conditions, and explore the influence of multi-level moderators (clinician characteristics, work environment) and mediators (fidelity) of treatment gains

Analyses

We hypothesize that improvements will be greater for parent–child dyads treated by clinicians in the CM condition followed by LC, clinic staff trained by clinicians in the CM group, and DE (in that order). Our basic approach will be to use ANOVA methods as in Aim 1 but with proper accounting of the nesting of dyads. We expect, on average, approximately one dyad per clinician; however, whenever we have more than one dyad for a clinician we will use the data from those dyads to estimate the associated variance component, which in turn we can use to test the fit of our model. In order to examine multi-level moderators and mediators of treatment, we will use the standard framework of Baron and Kenney [88] and as elaborated by Kraemer et al. [89] to test for moderators and mediators. We regard these analyses as exploratory because tests of interactions are often not as powerful as those for main effects.

Proposed statistical analyses

After collecting and organizing the data, we will begin with simple graphical and numerical summaries to (for example) check for unusual observations and to assess patterns of missing data. We will then address the main aims beginning with the simplest version of the hypotheses, which in this case, will typically require an ANOVA (paying attention to the nested design) to compare training conditions. We will then do a more nuanced study of the data using appropriate (e.g., linear, logistic) regression models to relate the outcomes to both features that we used to balance the randomization, covariates such as those we balance on (population size, poverty level) and other covariates that appear to be related to differences between training conditions.

Nesting

An important feature of this study is that it is a nested design: the clinicians are nested within clinic, and the parent–child dyad is nested within a clinician. Thus, the models that we will use to compare outcomes across treatment groups will incorporate that feature, and tests of hypotheses will involve a careful study of the resulting variance components. As a simple example at the dyad level, consider the CBCL total outcome: the model that we will consider models is Y(ijk) = m + t(i) + s(j) + c(k(j)) + error(ijk), where m is the grand mean, t(i) is the effect of training condition i, s(j) is the effect of clinic (k), c(k(j)) is the effect of clinician j, who is nested in site k, and error (ijk) is the variation unaccounted for by the covariates in the model. We will consider the use of random effects to model the (likely presence of) correlation between measures within a clinic. To fit these models and to test our hypotheses, we will use PROC MIXED in SAS.

Missing data

We recognize that missing data will occur because of attrition and other reasons. We will use an intent-to-treat approach: that is, a participant (e.g., clinician or dyad) who is randomized to a particular training condition will be included in the analysis whether they drop out or not. Our general approach to missing data will follow that of Little and Rubin [90]. Because the reasons for missingness may be difficult to ascertain, we will use sensitivity analysis.

Trial status

To date, all four waves of training have been initiated. Training efforts and clinical consultation will continue through 2016. County and clinic recruitment is now complete, with 50 clinics, representing 37 randomization units enrolled in the study, which is lower than the originally predicted enrollment of 72 clinics [91]. From participating agencies, 100 clinicians, 50 supervisors, and 50 administrators have been enrolled. Additionally, 26 “second generation” clinicians have been enrolled and will continue to be enrolled as the study progresses. At the time of the manuscript acceptance (9/16/15), 203 families had consented to participate in the study; 198 families had completed the baseline assessment. Family enrollment is expected to continue through December 31, 2016, and it is anticipated that family enrollment will surpass the target of 288. Thus far, retention rates have varied across participant types but have remained high. As indicated above, we anticipate a 96 % retention rate for professional participants; to date, 94 % of professionals have been retained. We anticipate an 88 % retention rate for families; to date, 95 % of families have been retained. Likewise, data collection thus far has yielded assessment completion rates of 93 % for professional participants and 86 % for families. A few study team decisions have influenced these rates: (1) we kept in the study all clinicians who left their original agencies and (2) (if possible) we included families from these clinicians who were seen in new agencies. We recognize that these rates currently are within or surpass the expected range; however, it is early in the study timeline, and many things likely will affect final rates.

Discussion

Innovation and anticipated contribution

This study offers a direct comparison of the effectiveness of three training models to implement PCIT, a well-establish EBT, within community settings. As indicated above, several reports (e.g., [25, 26]) note a lack of access to EBTs within community settings. The field’s lack of successful implementation may be related to a lack of empirical attention devoted specifically to training models. To date, the most common way to train community therapists has been to ask them to read written materials or attend workshops. There is little to no evidence that these “train and hope” approaches [92] will result in increases in skill and competence [28, 93]. Although the examined training methods are becoming more commonly used to implement EBTs in community settings, limited data exist for each training method. No trials were found that included a comparison of these training conditions, and few studies [94] have directly compared active training conditions. In order to implement each training condition, great strides were taken to study and operationalize each training protocol (e.g., [95]. This study will explore outcomes at several levels (i.e., administrators, supervisors, clinicians, and families) and across training conditions (i.e., Learning Collaborative (LC), Cascading Model (CM), and Distance Education (DE)). In turn, the study protocol and findings are anticipated to contribute substantially to the literature and field by examining the effectiveness of training practices of EBTs for professionals working in real-world, community settings, connecting training models to client outcomes, and examining broader public health implications by exploring the cost, feasibility, and far-reaching impact of each training model on community systems.

Practical and operational issues

Although this trial offers an innovative exploration of the implementation of an EBT within community settings, this strength also brings unique challenges. The context of the current study required frequent and thoughtful consideration of the methodological challenges that real-world circumstances presented over the course of the study.

As anticipated, movement and turnover of professional participants (i.e., administrators, supervisors, and clinicians) occurred throughout the course of the study, although this movement may impact the collection of client level data; to date, the rate of staff turnover has been lower (19 % within a one year time frame) than anticipated (35 % or higher) [120, 121]. By using an intent-to-train model, the study design allows for the continued tracking of professionals, as they change employment location or status. Through this design, we are able to continually collect data on clinician use of PCIT, as well as family outcomes, regardless of staff movement. Participating professionals were not replaced at the clinic level. This allowed for data collection to remain consistent over time while providing information about the frequency and nature of staff movement occurring in community mental health settings.

Demands unrelated to the study were placed on agencies during the study timeframe. For example, agencies reported experiencing an increasing number of audits, monitoring, and site visits from payer organizations and regulating bodies. In addition, several agencies reported administrative restructuring or clinic reorganization, which often resulted in staff turnover. One clinic reported that reorganizing resulted in about 30 % of staff leaving the organization within a few weeks, which impacted the roles and demands of participating team members.

The scale of this community-based study spanning across 50 agencies in 37 mental health systems led to additional considerations specific to project implementation. For example, study commitment was variable across participating professionals, organizations, and counties and has changed over time. The nature of receiving free training and support may have impacted the engagement of professionals over time. Other organization initiatives (e.g., implementing other EBTs, developing a new program) over the course of the study may have also contributed. Several components of data collection (e.g., fidelity monitoring, evaluation of clinician, and parent skill) relied on clinicians submitting video recordings of treatment sessions, and clinicians expressed a variety of barriers to successful submission of session recordings, including difficulty with technology, lack of access to computers, limited time, and reluctance to be recorded.

Challenges also exited for our research team such as the need for experienced personnel (e.g., trainers), extensive travel, and broad scale recruitment and retention efforts made this an expensive trial. Also, an online data collection system was developed because participants were located across a large geographic area, which changed many of our team’s established recruitment and retention strategies.

Conclusions

This trial is a novel exploration of the effectiveness of three training models (Learning Collaborative (LC), Cascading Model (CM), and Distance Education (DE)) to implement a well-established EBT in real-world, community settings. The project is guided by three specific aims: (1) to build knowledge about training outcomes, (2) to build knowledge about implementation outcomes, and (3) to understand the impact of training clinicians using LC, CM, and DE models on client outcomes. This study will provide timely and relevant information to the field of implementation science, while also contributing to the broader public health impact by providing training, support, and resources to an existing workforce of service providers as well as increasing the availability of an EBT for families served in existing communities.

Abbreviations

- CM:

-

Cascading Model training

- DBDs:

-

disruptive behavior disorders

- DE:

-

Distance Education training

- EBTs:

-

evidence-based treatments

- LC:

-

Learning Collaborative

- PCIT:

-

Parent–Child Interaction Therapy

References

Lavigne JV, Gibbons RD, Christoffel KK, Rosenbaum D, Binns H, Dawson N, et al. Prevalence rates and correlates of psychiatric disorders among preschool children. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 1996;35(2):204–14.

Tremblay RE, Pihl RO, Vitaro F, Dobkin PL. Predicting early onset of male antisocial behavior from preschool behavior. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 1994;51(9):732–6.

Block J, Block JH, Keyes S. Longitudinally foretelling drug usage in adolescence: early childhood personality and environmental precursors. Child Dev. 1988;59(2):336–55.

Caspi A, Moffitt TE, Newman DL, Silva PA. Behavioral observations at age 3 years predict adult psychiatric disorders. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 1996;53:1033–9.

Egger H. Toddler with temper tantrums: A careful assessment of a dysregulated preschool child. In: Galanter CA, Jensen P, editors. DSM-IV-TR casebook and treatment guide for child mental health. Arlington, VA, US: Am Psychiatr US; 2009. p. 365–84.

Campbell SB. Behavior problems in preschool children: a review of recent research. J Child Psychol Psychiatry. 1995;36:113–49.

Kessler RC, Berglund P, Demler O, Jin R, Merikangas KR, Walers RR. Lifetime prevalence and age-of-onset distributions of DSM-IV disorders in the National Comorbidity Survey Replication. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2005;62:593–603.

Kazdin AE. Conduct disorders in childhood and adolescence. 2nd ed. Thousand Oaks: Sage; 1995.

Schumann E, Durning P, Eyberg SM, Boggs SR. Screening for conduct problem behavior in pediatric settings using the Eyberg Child Behavior Inventory. Ambul Child Health. 1996;2:35–41.

Brestan EV, Eyberg SM. Effective pscyhosocial treatments of conduct-disordered children and adolescents: 29 years, 82 studies, and 5,272 kids. J Clin Psychol. 1998;27(2):180–9.

Eyberg SM. Members of the Child Study Laboratory. Parent–child Interaction Therapy: integrity checklists and session materials. 1999.

Herschell AD, Calzada EJ, Eyberg SM, McNeil CB. Parent–child interaction therapy: new directions in research. Cogn Behav Pract. 2002;9:9–16.

Gallagher N. Effects of Parent–child Interaction Therapy on young children with disruptive behavior disorders. Bridges Practice-Based Res Syntheses. 2003;1:1–17.

Thomas R, Simmer-Gembeck MJ. Behavioral outcomes of Parent–child Interaction Therapy and Triple P-Positive Parenting Program: a review and meta-analysis. J Abnorm Child Psychol. 2007;35:475–95.

Eisenstadt TH, Eyberg SM, McNeil CB, Newcomb K, Funderburk B. Parent–child interaction therapy with behavior problem children: relative effectiveness of two stages and overall treatment outcome. J Clin Child Psychol. 1993;22:42–51.

McNeil CB, Clemens-Mowrer L, Gurwitch RH, Funderbunk BW. Assessment of a new procedure to prevent timeout escape in preschoolers. Child Fam Behav Ther. 1994;16(3):27–35.

Schuhmann E, Foote R, Eyberg SM, Boggs SR, Algina J. Parent–child interaction therapy: interim report of a randomized trial with short-term maintenance. J Clin Child Psychol. 1998;27:34–45.

Boggs SR, Eyberg SM, Edwards DL, Rayfield A, Jacobs J, Bagner D, et al. Outcomes of Parent–child Interaction Therapy: a comparison of treatment completers and study dropouts one to three years later. Child Fam Behav Ther. 2004;26:1–22.

Eyberg SM, Funderbunk BW, Hembree-Kigin T, McNeil CB, Querido JG, Hood KK. Parent–child interaction therapy with behavior problem children: one and two year maintenance of treatment effects in the family. Child Fam Behav Ther. 2001;23:1–20.

Funderburk B, Eyberg SM, Newcomb K, McNeil CB, Hembree-Kigin T, Capage L. Parent–child Interaction Therapy with behavior problem children: maintenance of treatment effects in the school setting. Child Fam Behav Ther. 1998;20:17–38.

Hood KK, Eyberg SM. Outcomes of Parent–child Interaction Therapy: mothers’ reports of maintenance three to six years after treatment. J Clin Child Adolesc Psychol. 2003;32(3):419–29.

Chaffin M, Silovsky JF, Funderburk B, Valle LA, Brestan EV, Balachova T, et al. Parent–child interaction therapy with physically abusive parents: efficacy for reducing future abuse reports. J Consult Clin Psychol. 2004;72:500–10.

Lanier P, Kohl PL, Benz J, Swinger D, Mousette P, Drake B. Parent–child interaction therapy in a community setting: examining outcomes, attrition, and treatment setting. Res Soc Work Pract. 2011;24(1):689–98.

Lyon AR, Budd KS. A community mental health implementation of Parent–child interaction therapy. J Child Fam Stud. 2010;19:654–68.

U.S. Public Health Service US Department of Health and Human Services, Office of the Surgeon General. Mental health. A report of the Surgeon General. Rockville, MD: Author; 2009.

President’s New Freedom Commission on Mental Health. Report of the President’s New Freedom Commission on Mental Health. 2004.

McHugh RK, Barlow DH. The dissemination and implementation of evidence-based psychological treatments: a review of the current efforts. Am Psychol. 2010;65(2):73–84.

Herschell AD, Kolko DJ, Baumann BL, Davis AC. The role of therapist training in the implementation of psychosocial treatments: a review and critique with recommendations. Clin Psychol Rev. 2010;30:448–66.

Institute for Healthcare Improvement. The breakthrough series: IHI’s collaborative model for achieveing breakthrough improvement in innovation series. Boston: Institute for Healthcare Improvement; 2003.

Kilo CM. A framework for collaborative improvement: lessons from the Institute for Healthcare Improvement’s breakthrough series. Qual Manag Health Care. 1998;6:1–13.

Markiewicz J, Ebert L, Ling D, Amaya-Jackson L, Kisiel C. Learning collaborative toolkit. National Center for Child Traumatic Stress: Los Angeles, CA and Durham, NC; 2006.

Flamm BL, Berwick DM, Kabcenall AI. Reducing cesarean section rates safely: lessons learned from a “breakthrough series” collaborative. Birth. 1998;25:117–24.

Lendon BE, Wilson IB, McInnes K, Landrum B, Hirschhon L, Marsden PV, et al. Effects of a quality improvement collaborative on the outcome care of patients with HIV infection: the EQHIV study. Ann Intern Med. 2004;140:887–96.

Glasgow RE, Funnell MM, Bonomi AE, Davis C, Beckham V, Wagner EH. Self-management aspects of the improving chronic illness care breakthrough series: Implementation with diabetes and heart failure. Ann Behav Med. 2002;24:80–7.

Cretin S, Shortell SM, Keller EB. An evaluation of collaborative interventions to improve chronic illness care: framework and study design. Eval Rev. 2004;28(1):28–51.

Young PC, Glade GB, Stoddard GJ, Norlin C. Evaluation of a learning collaborative to improve the delivery of preventive services by pediatric practices. Pediatrics. 2006;117(5):1469–79.

Ebert L, Amaya-Jackson L, Markiewicz J, Kisiel C, Fairbank J. Use of the breakthrough series collaborative to support broad and sustained use of evidence-based trauma treatment for children in community practice settings. Adm Policy Ment Health. 2011:1–13. doi:10.1007/s10488-011-0347-y.

Cavaleri MA, Gopalan G, McKay M, Appel A, Bannon Jr WM, Bigley MF, et al. Impact of a learning collaborative to improve child mental health service use among low-income urban youth and families. Best Pract Ment Health. 2006;2(2):67–79.

Cavaleri MA, Franco LM, McKay M, Appel A, Bannon Jr WM, Bigley MF, et al. The sustainability of a learning collaborative to improve mental health service use among low-income urban youth and families. Best Pract Ment Health. 2007;3(2):52–61.

Cavaleri MA, Perez M, Burton G, Penn M, Beharie N, Hoagwood KE. Developing the Support, Teambuilding, and Referral (STAR) Intervention: a research/community partnership. Child Adolesc Ment Health. 2010;15(1):56–9.

Rutkowski BA, Gallon S, Rawson RA, Freese TE, Bruehl A, Crevecoeur-MacPhail D, et al. Improving client engagement and retention in treatment: The Los Angeles County experience. J Subst Abuse Treat. 2010;39:78–86.

Solberg LI, Kottke TE, Brekke ML, Magnan S, Davidson G, Calomeni CA, et al. Failure of a continuous quality improvement intervention to increase the delivery of preventative services: a randomized trial. Eff Clin Pract. 2000;3(3):105–15.

Rogers ES, Cohen BF, Danley KS, Hutschinson D, Anthony WA. Training mental health workers in psychiatric rehabilitation. Schizophr Bull. 1986;12(4):709–19.

Chamberlain P, Price J, Reid J, Landsverk J. Cascading implementation of a foster and kinship parent intervention. Child Welfare. 2008;87(5):27.

Hein D, Litt LC, Cohen L, Miele GM, Campbell A. Preparing, training, and integrating staff in providing integrated treatment. In: Trauma services for women in substance abuse: an integrated approach. Washington D.C: American Psychological Association; 2009. p. 143–61.

Martino S, Brigham GS, Higgins C, Gallon S, Freese TE, Albright LM, et al. Partnerships and pathways of dissemination: the NIDA-SAMHSA Blending Initiative in the Clinical Trials Network. J Subst Abuse Treat. 2010;38 Suppl 1:S31–43.

Coogle CL. The families who care project: meeting educational needs of African American and rural family caregivers dealing with dementia. Educ Gerontol. 2002;28(1):59–71.

Gabel LL, Pearsol JA. The twin epidemics of substance use and HIV: a state-level response using a train-the-trainer model. Fam Pract. 1993;10(4):400–5.

Jason LA, Lapp C, Kenney KK, Lupton T. An innovative approach in training health care workers to diagnose and manage patients with CFS. In: Alexandra AM, editor. Advances in pyschology research. Hauppauge, NY: Nova Science Publishers; 2008. p. 273–81.

Nyamathi A, Vatsa M, Khakha DC, McNeese-Smith D, Leake B, Fahey JL. HIV knowledge improvement among nurses in India: using a train-the-trainer program. JANAC. 2008;19(6):443–9.

Pullum JD, Sanddal ND, Obbink K. Training for rural prehospital providers: a retrospective analysis from Montana. Prehosp Emerg Care. 1999;3(3):231–8.

Tibbles LR, Smith AE, Manzi SC. Train-the-trainer for hospital-wide safety training. J Nurs Staff Dev. 1993;9(6):266–9.

Virani R, Malloy P, Ferrell BR, Kelly K. Statewide efforts in promoting palliative care. J Palliat Med. 2008;11(7):991–6.

Booth-Kewley S, Gilman PA, Shaffer RA, Brodine SK. Evaluation of sexually transmitted disease/human immunodeficiency virus prevention train-the-trainer program. Mil Med. 2001;166(4):304–10.

Coogle CL, Osgood NJ, Parham IA. A statewide model detection and prevention program for geriatric alcoholism and alcohol abuse: increased knowledge among service providers. Community Ment Health J. 2000;36(2):137–48.

Gadomski AM, Wolff D, Tripp M, Lewis C, Short LM. Changes in health care providers’ knowledge, attitudes, beliefs, and behaviors regarding domestic violence, following a multifaceted intervention. Acad Med. 2001;76(10):1045–52.

Moon RY, Calabrese T, Aird L. Reducing the risk of sudden infanct death syndrome in child care and changing provider practices: lessons learned from a demonstration project. Pediatrics. 2008;122(4):788–98.

Tziraki C, Graubard BI, Manley M, Kosary C, Moler JE, Edwards BK. Effect of training on adoption of cancer prevention nutrition-related activities by primary care practices: results of a randomized, controlled study. JGIM. 2000;15(3):155–62.

Well M, Stokols D, McMahan S, Clitheroe C. Evaluation of a worksite injury and illness prevention program: do the effects of the REACH OUT training program reach the employees? J Occup Health Psychol. 1997;2(1):25–34.

Zapata LB, Coreil J, Entrekin N. Evaluation of triple touch: an assessment of program delivery. Cancer Pract. 2001;9 Suppl 1:S23–30.

Demchak M, Browder DM. An evaluation of the pyramid model of staff training in group homes for adults with severe handicaps. Educ Train Ment Retard. 1990;25(2):150–63.

Shore BA, Iwata BA, Vollmer TR, Lerman DC, Zarcone JR. Pyramidal staff training in the extension of treatment for severe behavior disorders. J Appl Behav Anal. 1995;28(3):323–30.

Anderson SE, Youngson SC. Introduction of a child sexual abuse policy in a health district. Child Soc. 1990;4:401–19.

Miller WR, Sorenson JL, Selzer JA, Brigham GS. Disseminating evidence-based practices in substance abuse treatment: a review with suggestions. J Subst Abuse Treat. 2006;31(1):25–39.

Worrall JM, Fruzzetti A. Improving peer supervision ratings of therapist performance in dialectical behavior therapy: an internet-based training system. Psychother Theory Res Pract Train. 2009;46(4):476–9.

Sholomskas DE, Syracuse-Siewert G, Rounsaville BJ, Ball SA, Nuro KF. We don’t train in vain: a dissemination trial of three strategies of training clinicians in cognitive behavioral therapy. J Consult Clin Psychol. 2005;73(1):106–15.

National Crime Victims Research & Treatment Center. TF-CBT web: first year report. Charleston, SC: Medical University of South Carolina; 2007.

Suda KT, Miltenberger RG. Evaluation of staff management strategies to increase positive interactions in a vocational setting. Behav Res Treat. 1993;8(2):69–88.

Miller WR, Yahne CE, Moyers TB, Martinez J, Pirritano M. A randomized trial of methods to help clinicians learn motivational learning. J Consult Clin Psychol. 2004;72(6):1050–62.

Sanders MR, Turner KMT, Markie-Dadds C. The development and dissemination of the Triple P-Positive Parenting Program: a multilevel, evidence-based system of parenting and family support. Prev Sci. 2002;3:173–89.

Ford JK, Weissbein DA. Training of transfer: an updated review. Perform Improv Q. 1997;10:22–41.

Proctor EK, Landsverk J, Aarons G, Chambers D, Glisson C, Mittman B. Implementation research in mental health services: an emerging science with conceptual, methodological, and training challenges. Adm Policy Ment Health. 2009;36:24–34.

Baldwin T, Ford JK. Transfer of training: a review and directions for future research. Pers Psychol. 1988;41:63–105.

Kraiger K, Ford JD, Salas E. Application of cognitive, skill-based, and affective theories of learning outcomes to new methods of training evaluation. J Appl Psychol. 1993;78:311–28.

Proctor EK, Silmere H, Raghavan R, Hovmand P, Aarons G, Bunger A et al. Outcomes for implementation research: conceptual distinctions, measurement challenges, and research agenda. Adm Policy Ment Health. 2010. doi:10.1007/s10488-010-0319-7.

Herschell AD, Kogan JN, Celedonia KL, Lindhiem O, Stein BD. Evaluation of an implementation initiative for embedding dialectical behavior therapy in community settings. Eval Program Plann. 2014;43:55–63.

Kolko DJ, Baumann BL, Herschell AD, Hart JA, Holden EA, Wisniewski SR. Implementation of AF-CBT with community practitioners serving child welfare and mental health: a randomized trial. Child Maltreat. in press.

Rollins AL, Salyers MP, Tsai J, Lydick JM. Staff turnover in a statewide implementation of ACT: Relationship with ACT fidelity and other team characteristics. Admin Policy Mental Health Mental Health Serv Res. 2010;37:417–26.

Woltmann EM, Whitley R, McHugo GJ, Brunette M, Torrey WC, Coots L, et al. The role of staff turnover in the implementation of evidence-based practices in mental health care. Psychiatr Serv. 2008;59(7):732–7.

Southam-Gerow MA, Weisz JR, Chu BC, McLeod BD, Gordis EB, Connor-Smith JK. Does cognitive behavioral therapy for youth anxiety outperform usual care in community clinics? An initial effectiveness test. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 2010;49(10):1043–52.

Weisz JR, Gordis EB, Chu BC, McLeod BD, Updegraff A, Southam-Gerow MA, et al. Cognitive-behavioral therapy versus usual clinical care for youth depression: an Initial test of transportability to community clinics and clinicians. J Consult Clin Psychol. 2009;77(3):383–96.

Chamberlain P, Brown CH, Saldana L, Reid J, Wand W, Marsenich L, et al. Engaging and recruiting counties in an experiment on implementing evidence-based practice in California. Adm Policy Ment Health. 2008;35:250–60.

Aarons GA, Wells RS, Zagursky K, Fettes DL, Palinkas LA. Implementing evidence-based practice in community mental health agencies: a multiple stakeholder analysis. Am J Public Health. 2009;99(11):2087–95. doi:10.2105/ajph.2009.161711.

Wang W, Saldana L, Brown CH, Chamberlain P. Factors that influenced county system leaders to implement an evidence-based program: a baseline survey within a randomized controlled trial. Implement Sci. 2010;5:72.

Eyberg SM, Funderburk B, McNeil CB, Niec L, Urquiza AJ, Zebbell NM. Training guidelines for parent–child interaction therapy. 2009.

TF-CBT web: a web-based learning course for trauma-focused cognitive-behavioral therapy. http://tfcbt.musc.edu (2005) Assessed 30 March 2015.

Proctor E, Silmere H, Raghavan R, Hovmand P, Aarons G, Bunger A, et al. Outcomes for implementation research: conceptual distinctions, measurement challenges, and research agenda. Admin Policy Mental Health Mental Health Serv Res. 2011;38(2):65–76.

Baron RM, Kenny DM. The moderator-mediator variable distinction in social psychological research: conceptual, strategic and statistical considerations. J Pers Soc Psychol. 1986;51:1173–82.

Kraemer HC et al. Mediators and moderators of treatment effects in randomized clinical trials. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2002;59:877–83.

Little R, Rubin D. Statistical analysis with missing data. John Wiley & Sons, Inc. Hoboken,NJ: 2002.

Cohen J. Statistical power analysis for the behavioral sciences. Hillsdale, NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum Associates, Inc; 1998. p. 2.

Henggeler SW, Schoenwald SK, Liao JG, Letourneau EJ, Edwards DL. Transporting efficacious treatments to field settings: the link between supervisory practices and therapist fidelity in MST programs. J Clin Child Adolesc Psychol. 2002;31(2):155–67.

Beidas RS, Kendall PC. Training therapists in evidence-based practice: a critical review of studies from a systems-contextual perspective. Clin Psychol Sci Pract. 2010;17(1):1–30.

Martino S, Ball S, Nich C, Canning-Ball M, Rounsaville B, Carroll K. Teaching community program clinicians motivational interviewing using expert and train-the-trainer strategies. Addiction. 2010;106(2):428–41.

Scudder AB, Herschell AD. Building an evidence-base for the training of evidence-based treatments: use of an expert informed approach. Child Youth Serv Rev. 2015;55:84–92.

Funderburk B, Nelson M. PCIT Coaches Quiz. 2014.

Funderburk B, Gurwitch R, Shanley J, Chase R, Nelson M, Bard E, et al. FIRST Coach Coding System for CDI Coaching Manual. 2014.

Kolko DJ. Treatment of child physical abuse: an effectiveness trial. 2012.

Herschell AD, McNeil CB, Urquiza AJ, McGrath JM, Zebbell NM, Timmer SG, et al. Evaluation of a treatment manual and workshops for disseminating, Parent–child Interaction Therapy. Admin Policy Mental Health Mental Health Serv Res. 2009;36:63–81.

Chafouleas SM, Briesch AM, Riley-Tillman TC, McCoach DB. Moving beyond assessment of treatment acceptability: an examination of the factor structure of the Usage Rating Profile—Intervention (URP-I). Sch Psychol Q. 2009;24:36–47.

Addis ME, Krasnow AD. A national survey of practicing psychologists’ attitudes toward psychotherapy treatment manuals. J Consulting Clin Psychol. 2000;68(2):331–9.

Schoenwald SK et al. A survey of the infrastructure for children’s mental health services: implications for the implementation of empirically supported treatments. Adm Policy Ment Health. 2008;35:84–97.

Hoagwood K, Schoenwald SK, Chapman JE. Dimensions of organizational readiness—revised (DOOR-R). Unpublished Instrument. 2003

Lehman WE, Greener JM, Simpson DD. Assessing organizational readiness for change. J Subst Abuse Treat. 2002;22(4):197–209.

Kolko DJ, Herschell AD, Baumann BL. Treatment Implementation Feedback Form. Unpublished Manuscript. Pittsburgh PA: University of Pittsburgh School of Medicine. 2006.

Kolko DJ, Dorn LD, Burkstein OG, Pardini D, Holden EA, Hart JD. Community vs. clinic-based modular treatment of children with early-onset ODD or CD: a clinical trial with three-year follow-up. J Abnorm Child Psychol. 2009;37:591–609.

Eyberg S, Funderburk B. Parent–Child Interaction Therapy protocol. PCIT International, Inc. Gainsville, FL: 2011.

Herschell AD. Translating an evidence-based treatment into community practice: implementing parent–child interaction therapy in an urban domestic violence shelter. 2011.

Olmstead T, Carroll K, Canning-Ball M, Martino S. Cost and cost-effectiveness of three strategies for training clinicians in motivational interviewing. in press.

Aarons GA. Evidence-based practice implementation: the impact of public versus private sector organization type on organizational support, provider attitudes, and adoption of evidence-based practice. Impl Sci. 2009;4:83.

Eyberg SM, Pincus D. Eyberg Child Behavior Inventory and Sutter-Eyberg Behavior Inventory: revised professional manual. Odessa, FL: Psychological Assessment Resources, Inc.; 2000.

Wolraich ML, Lambert W, Doffing MA, Bickman L, Simmons T, Worley K. Psychometric properties of the Vanderbilt ADHD diagnostic parent rating scale in a referred population. J Pediatr Psychol. 2003;28(8):559–68.

Frick PJ, Hare RD. Antisocial process screening device: APSD. Toronto: Multi-Health Systems; 2001.

Kroenke K, Spitzer RL, Williams JB. The Phq‐9. JGIM. 2001;16(9):606–13.

Spitzer RL, Kroenke K, Williams JB, Löwe B. A brief measure for assessing generalized anxiety disorder: the GAD-7. Arch Intern Med. 2006;166(10):1092–7.

Elgar FJ, Waschbusch DA, Dadds MR, Sigvaldason N. Development and validation of a short form of the Alabama Parenting Questionnaire. J Child Fam Stud. 2007;16(2):243–59.

Kazdin AE, Holland L, Crowley M, Breton S. Barriers to treatment participation scale: evaluation and validation in the context of child outpatient treatment. J Child Psychol Psychiatry. 1997;38(8):1051–62.

Brestan EV, Jacobs JR, Rayfield AD, Eyberg SM. A consumer satisfaction measure for parent–child treatments and its relation to measures of child behavior change. Behav Ther. 2000;30(1):17–30.

Gyamfi P, Walrath C, Burns BJ, Stephens RL, Geng Y, Stambaugh L. Family education and support services in systems of care. J Emotion Behav Disord. 2009;18(1):14–26.

Ben-Dror R. Employee turnover in community mental health organizations: A developmental stages study. Community Ment Health J. 1994;30:14.

Sheidow AJ, Schoenwald SK, Wagner HR, Allred CA, & Burns BJ. Predictors of workforce turnover in a tranposted treatment program. Adm Policy Ment Health and Ment Health Serv Res. 2007;34(1):45–56.

Acknowledgements

This project has been guided by a statewide steering committee. We gratefully acknowledge the substantial contribution of the following steering committee members: Harriet Bicksler, Darlene Black, Kimberly Blair, Diana Borges, Brian Bumbarger, Amanda Clouse, Leigh Carlson-Hernandez, Judy Dogin, Susan Dougherty, Robert Gallen, Jim Gavin, Jennifer Geiger, Gordon Hodas, Jill Kachmar, Donna Mick, Doug Muetzel, Denise Namowicz, Connell O’Brien, Andrea Richardson, Ronnie Rubin, Doug Spencer, Michele Walsh, and Priscilla Zorichak.

This project also has benefitted by the feedback provided by the following PCIT Experts: Rhea Chase, Sheila Eyberg, Cheryl McNeil, and Melanie Nelson. We also acknowledge Abigail Reed for her role in helping to prepare the grant application.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Authors’ contributions

AH, the study principal investigator, conceived of the study and participated in the design, execution, and write-up of the study. She also is responsible for study oversight. DK participated in the design, execution, and write-up of the study. AS, ST, and KS participated in operationalizing procedures, training, and writing. SH participated in operationalizing procedures, coordinating the study, and recruiting participants. SI, MC, and SM participated in the design, execution, and write-up of the study. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made. The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver (http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/) applies to the data made available in this article, unless otherwise stated.

About this article

Cite this article

Herschell, A.D., Kolko, D.J., Scudder, A.T. et al. Protocol for a statewide randomized controlled trial to compare three training models for implementing an evidence-based treatment. Implementation Sci 10, 133 (2015). https://doi.org/10.1186/s13012-015-0324-z

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s13012-015-0324-z