Abstract

Background

The Baltic countries–Lithuania, Latvia and Estonia–are characterized by a high rate of fully alcohol-attributable mortality, compared with Poland. Alcohol control policy measures implemented since 2001 in the Baltic countries included a restriction on availability and an increase in excise taxation, among others. The aim of the current study was to evaluate the relationship between alcohol control policy implementation and alcohol-attributable mortality in the Baltic countries and Poland.

Methods

Alcohol-attributable mortality data for 2001–2020 was defined by codes 100% alcohol-attributable for persons aged 15 years and older in the Baltic countries and Poland. Alcohol control policies implemented between 2001 and 2020 were identified, and their impact on alcohol-attributable mortality was evaluated using an interrupted time-series methodology by employing a generalized additive model.

Results

Alcohol-attributable mortality was significantly higher in the Baltic countries, compared with Poland, for both males and females. In the final reduced model, alcohol control policy significantly reduced male alcohol-attributable mortality by 7.60% in the 12 months post-policy implementation. For females, the alcohol control policy mean-shift effect was higher, resulting in a significant reduction of alcohol-attributable mortality by 10.77% in the 12 months post-policy implementation. The interaction effects of countries and policy tested in the full model were not statistically significant, which indicated that the impact of alcohol control policy on alcohol-attributable mortality did not differ across countries for both males and females.

Conclusions

Based on the findings of the current study, alcohol control policy in the form of reduced availability and increased taxation was associated with a reduction in alcohol-attributable mortality among both males and females.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Central and Eastern European countries have the highest alcohol per capita consumption in the European region and, in turn, also have a high alcohol-attributable disease burden [1]. Alcohol consumption has been causally linked to more than 200 diseases, injuries, and other health conditions, including alcoholic liver disease, alcoholic cardiomyopathy, specific cancers, and mental or behavioral disorders [2, 3]. In the case of Estonia, Latvia, and Lithuania–the Baltic countries (BC)–the mortality attributable to alcohol-related chronic liver and cardiovascular diseases (CVD) is particularly high [4,5,6,7], which is at least partly explained by specific alcohol consumption patterns (i.e., binge drinking) that characterize these countries, as demonstrated in previous studies [8, 9].

Over the past 30 years, the BC has undergone a societal transformation that has substantially impacted health outcomes and brought significant changes to people’s health behavior. Alcohol consumption is one such example. During the last two decades, alcohol consumption has been similar across the BC, with 10 to 15 L of absolute alcohol being consumed annually per person aged 15 years and older, much higher than the global average [10, 11]. Over the past two decades, some alcohol control policy (ACP) measures have been implemented in the BC [12], which were expected to influence both overall and alcohol-attributable mortality trends in these countries [13]. During those years, significant economic changes took place in the BC, such as the 2008–2009 global financial crisis, which reduced gross domestic product (GDP) and decreased people's ability to purchase certain products, including alcohol. Adopting effective ACP is important to reduce mortality from alcohol-attributable diseases [12]. The most cost-effective policies recommended by the World Health Organization (WHO) (commonly referred to as the “best buys”) include advertising bans, increasing taxes on alcoholic beverages, and reducing the availability of alcohol [14]. Of the three ACP measures, increased taxation and reduced availability are expected to have an immediate impact on alcohol consumption, while advertising bans are expected to have a lagged effect [15, 16].

The implementation of ACP in the BC has been shown to reduce alcohol consumption and change drinking habits [12, 13]. ACP measures, such as a ban on advertising, reduction in the availability of alcohol, and increase in excise taxes on alcohol, implemented in Lithuania have led to significant positive changes in overall mortality and life expectancy [13, 17].

The BC and Poland implemented several ACP measures at various times from 2001 to 2020. In the BC, the number of implemented ACP measures increased around 2008, following the “year of sobriety” in Lithuania and the start of the global economic crisis in all three of the BC, while in Poland, only two ACP enactments were observed [18]. There were also two instances when the alcohol excise tax was reduced (in Poland in 2002 and Estonia in 2019) [16]. In addition to all-cause mortality, which seems to have been the focus of several of the latest studies in Europe [13, 19, 20], alcohol-attributable mortality is undoubtedly the most important criterion for evaluating the impact of ACP measures, as it is necessary for establishing the causal pathway.

Thus, the aim of the current study was to evaluate the relationship between ACP measures (increased taxation and reduced availability) and alcohol-attributable mortality in the BC and Poland.

Methods

This observational study utilized monthly alcohol-attributable mortality data from 2001 to 2020 (n = 240 months) for the BC and from 2001 to 2019 for Poland (n = 228 months).

Alcohol control policy measures

The ACP measure was ascertained via a review of relevant legislation in different countries and following the previous work by Rehm et al. (2022) [16] and Miščikienė et al. (2020) [18]. During the period of investigation, the following 18 ACP implementation time points were evaluated: in Estonia – seven tax increases and one availability reduction, in Latvia – four tax increases and one availability reduction, in Lithuania – two tax increases and two availability reductions, and in Poland – one tax increase. All ACP measures implemented during the analyzed period in the BC and Poland are presented in detail in Table 1. The procedures used to select the ACP measures modeled are described in detail elsewhere [15, 16]. The alcohol excise tax policies were included if the increase resulted in reduced affordability compared to the previous year, and the availability restriction policies were included if they reduced alcohol availability by at least 20%.

Each ACP was assumed to have an immediate impact that lasted 12 months and thus, was assigned a dummy variable, which was set to zero before the implementation of the ACP, then set to one for 12 months after the ACP was implemented, and set back to zero following the 12 months. A combined ACP dummy variable was also considered for each country. It was constructed in the following way: if any of the country's ACPs were active in each month the dummy variable was set to one. Otherwise, this dummy variable was set to zero. This allowed us to collectively assess the impact of all ACPs enacted in all countries simultaneously.

Mortality data

The sex-specific monthly alcohol-attributable mortality data were obtained by request for Lithuania from Statistics Lithuania and the State Register of Deaths and its Causes at the Institute of Hygiene, for Latvia from the Center for Disease Prevention and Control, for Estonia from the Estonian Cause of Death Registry, and for Poland from the National Statistical Office. The mortality data were obtained for individuals aged 15 years and older.

In total, 27 alcohol-attributable causes of death (five main and 22 additional) based on 10th Revision International Classification of Diseases (ICD-10) codes [21] were selected (Table 2). The specified causes of death are those that are fully attributable to alcohol with an alcohol-attributable fraction (AAF) of 100%, where AAF denotes the proportion of a certain disease category that would not have occurred had there been no alcohol consumption [22].

The BC and Poland used ICD-10 codes and the same death coding principles, however, the procedures have slightly changed over the study period and varied by country. A death certificate was issued by physicians in each of the study countries both in outpatient and inpatient health institutions. When recording the cause of death of a deceased person on the death certificate, the physicians relied on the information contained in the outpatient and inpatient medical records. Only those codes on the death certificates that were indicated as the main cause of death were included in the current analysis.

Control variables

The economic recession was controlled for in each model and was defined by a decrease in GDP based on purchasing power parities (GDP-PPP) using data from OECD [10]. The respective variable was country-specific, as the economic recession affected each of the countries at slightly different time points (see Supplementary material, Annex 1, Table 1S).

Statistical analyses

For all four countries, monthly time series consisting of age-standardized alcohol-attributable mortality rates per 100,000 population were analyzed. The proportion of alcohol-attributable deaths among total deaths was estimated as a percentage. Age-standardization was done using the European standard population in 2013 for those 15 years and older [23]. Statistical significance was set at p < 0.05. All statistical analyses were performed using R version 3.6.3 [24].

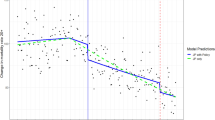

To test our hypothesis that ACP was associated with a reduction in alcohol-attributable mortality in BC and Poland, we performed interrupted time-series analyses by employing a generalized additive model (GAM) for both males and females [25]. All GAM models controlled for the economic recession using a dummy coded variable, coded as 1 during the months affected by the recession, and 0 for all other months. Countries were included and represented by a categorical variable, with Poland as the reference category. That is, the country of Poland was assigned a value of 0, and Estonia, Latvia and Lithuania were assigned values of 1, 2, and 3, respectively. Therefore, the coefficients of country effects are interpreted with respect to Poland. The log-transformed age-standardized alcohol-attributable mortality rates were approximately normally distributed, allowing for the use of linear models, and easily transformed into percentage change by exponentiating the coefficients, subtracting one from this number, and multiplying by 100 [26]. Seasonality was adjusted by adding smoothing splines representing monthly and yearly patterns. Residuals were examined with plots of the autocorrelation function and partial autocorrelation function to determine the autoregressive and moving average series orders (see Supplementary material, Annex 2).

For each sex, we presented a full model and a reduced model. Included in the full model were, in addition to the outcome, the linear time trend, ACP, economic recession, countries and the interactions between ACP and each of the countries, as well as the smooth terms. The outcome, alcohol-attributable mortality, was log-transformed to stabilize variance over time. Akaike Information Criterion (AIC) and R-squared were used to assist with selecting the most appropriate model [27]. A lower AIC value indicates a better fit; as such, the model with the lowest AIC was selected. The full model was further optimized to a reduced model by removing non-significant covariates if their inclusion did not improve model fit (as per the AIC or R-squared). Lastly, Chi-square difference tests were used to evaluate whether the full model fit significantly better than the reduced model [28]. All GAM models were conducted using the “mgcv” package in R [29].

To further investigate which ACPs were most effective, interventional Autoregressive Integrated Moving Average (ARIMA) models were developed to estimate the effect of individual ACP intervention while controlling for autocorrelation. ARIMA models were fitted using standard techniques, with AIC as an indicator of model fit. The seasonality was set to be 12 months due to the monthly data.

For each country and policy pair, a seasonal ARIMA model with exogenous variables was estimated (this is denoted as a SARIMAX(p,d,q)(P,D,Q)12 model, with specific values of (p,d,q) and (P,D,Q) selected to obtain the best fit to the data). Corrected Akaike’s Information Criterion (AICc) was used to evaluate the quality of the models, with lower values of AICc indicating a better fit to the data. The main parameter related to the impact of a given policy is the coefficient of the exogenous dummy variable corresponding to that specific policy (reported as the Policy effect coefficient). Assuming the effect is significant, a positive policy effect coefficient indicates an increase in mortality in the months following the policy’s implementation, while a negative value implies a congruent decrease in mortality [30]. All ARIMA models were done using the “forecast” package in R [31].

Results

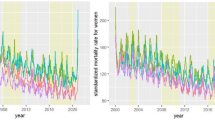

Figures 1 and 2 show the age-standardized alcohol-attributable mortality rates for males and females, respectively, over time. Both time series had some evidence of seasonal variation and non-linear trends over time.

During the study period, the average age-standardized alcohol-attributable mortality rate for males was 8.48 per 100,000 population in Estonia, 7.20 per 100,000 population in Latvia, 7.57 per 100,000 population in Lithuania, and 4.61 per 100,000 population in Poland. The age-standardized alcohol-attributable mortality rate for females was substantially lower compared to males in all four countries: 2.55, 2.21, 2.63, and 1.20 per 100,000 population in Estonia, Latvia, Lithuania, and Poland, respectively.

From 2001 to 2020, the average proportion of alcohol-attributable deaths of total deaths among males was 4.1% in Estonia, 3.1% in Latvia, 3.3% in Lithuania, and 2.5% in Poland. The proportion of alcohol-attributable deaths of total deaths among females was lower and accounted for 2.3%, 1.7%, 2.1%, and 1.1% in Estonia, Latvia, Lithuania, and Poland, respectively.

Effects of countries

For males, both the “full” model and “reduced” model showed that, on average, Estonia, Latvia, and Lithuania all had higher alcohol-attributable mortality rates than Poland. The reduced model showed that Estonia had an 83.68% (exp(0.616)-1) higher alcohol-attributable mortality rate than Poland, Latvia had a 58.10% higher rate, and Lithuania had a 59.35% higher rate. The impact of ACP did not differ by country, as the interaction effects of countries with ACP in the full model were not statistically significant (Table 3).

For females, similar effects were observed. All three of the BC had higher age-standardized alcohol-attributable mortality rates than Poland: Estonia had a rate that was 104.01% higher, Latvia had a rate that was 84.04% higher, and Lithuania had a rate that was 105.85% higher (Table 4). The interaction effects between countries and ACP in the full model were not statistically significant in the model for females, indicating that the association between ACP and alcohol-attributable mortality rates was not significantly different across countries.

Effects of policy

In the final reduced model for males, ACP had a significant effect on the alcohol-attributable mortality rate (-0.079 (95% CI -0.120, -0.038; p < 0.001)), which translates to a reduction of 7.60%. Given the different populations in the countries, this corresponds to an average effect of about 29, 39, 41, and 650 alcohol-attributable deaths avoided for Estonia, Latvia, Lithuania, and Poland, respectively, within one year after introducing a policy. As per the non-significant interaction term, the ACP had a similar impact in all four countries (Table 3).

For the final reduced model for females, the ACP mean-shift effect was notably higher -0.114 (95% CI -0.169, -0.059; p < 0.001)), which translates to a 10.77% reduction in alcohol-attributable mortality rates. This corresponds to average effects of around 14, 19, 28, and 291 deaths avoided within one year of policy implementation for Estonia, Latvia, Lithuania, and Poland, respectively (Table 4). Similar to males, the impact of APC and the alcohol-attributable mortality rate among females did not differ by country.

The ARIMA models for individual policies (see Table 1S in Annex 1) indicated that most policies were associated with a decrease in alcohol-attributable mortality rates. The 2009 and 2019 tax increases were significantly associated with a reduction in the alcohol-attributable mortality rate among females in Latvia.

Discussion

Over the past two decades, age-standardized alcohol-attributable mortality rates for both males and females have decreased significantly in most countries of the WHO European Region, but there are still clear differences between individual European regions, with Eastern Europe and the BC standing out among them [32]. During 2001–2020, alcohol-attributable deaths in the BC and Poland varied between 2.5% and 4.1% of all causes of death for males and between 1.1% and 2.3% for females. This difference between males and females is likely dependent on the fact that the number of males who abuse alcohol in the countries under investigation is much higher than females, that males consume alcoholic beverages more often than females, and the amount of alcohol they drink is higher, which causes significantly greater harm of alcohol consumption [33, 34].

During 2001–2020, the BC had a higher level of alcohol consumption and alcohol-attributable mortality than Poland. In recent years the gap in alcohol consumption between the BC and Poland has declined [35]. However, compared to Poland, the alcohol-attributable mortality rate and proportions of alcohol-attributable deaths among all deaths in the BC remained high.

The different alcohol-attributable mortality rates in the BC and Poland could be partially related to differences in the coding of causes of death. A truly refined coding of the cause of death depends on anamnestic data, lifestyle, the clinical manifestation of existing diseases or pathological conditions, refined clinical diagnosis through various laboratory or instrumental tests, and after death through a pathoanatomical examination. Over the past two decades, the frequency of post-mortem examinations has decreased significantly, reaching only 10% in Lithuania in 2020, making it difficult to determine the exact cause of death [36]. Most physicians judge the final cause of death based on clinical findings or pre-existing conditions that were recently diagnosed. This may introduce some uncertainty into the assessment of the actual cause of death, especially when explaining rarer clinical conditions or causes of death. It should be noted that in our study we examined 27 fully alcohol-attributable causes of death, out of which five main causes accounted for more than 90% of all fully alcohol-attributable deaths in the BC and Poland. According to Rehm and colleagues, many more cause-of-death codes could be attributed to alcohol [22], such as partially alcohol-attributable or injuries [22, 37]. A previous study found that there has been a decline in Lithuanian male and female mortality from cardiovascular diseases over the past two decades, especially since 2008–2009 when ACPs were implemented [6].

Our study indicated that ACP was associated with a reduction in alcohol-attributable mortality by 7.60% on average among males within 12 months after the implementation of the ACP. The impact of ACP measures on alcohol-attributable mortality among females amounted to an average of 10.77% in the 12 months post-implementation. There are several explanations for why ACP had a greater impact on alcohol-attributable mortality rates among females in the BC compared to their male counterparts. For instance, in 2020, more than 75% of the population consuming harmful amounts of alcohol were males [33]. Males are diagnosed with alcohol use disorders four to five times more often than females, males consume more alcohol per drinking episode on average and are more prone to acute behavioral problems related to alcohol use compared to females [38]. However, in females, problematic alcohol consumption develops faster due to bio-physiological processes [39].

Given the ecological study design, it is important to note that causality cannot be established for the associations found in the current study. However, given the different time points of ACP implementation, the multiple control via other countries, and the similarity of effect sizes irrespective of time and countries of implementation make alternative explanations relatively implausible [40].

The interaction effects of countries with ACP were not statistically significant in the full model, indicating that the ACP impacts did not differ by country for both males and females. Similar findings were found when the association between ACP and all-cause mortality was evaluated in the BC and Poland [20]. Taxation increases and availability restrictions had an effect in all countries, on average significantly reducing the age-standardized all-cause mortality rate among males [20]. Other studies have also shown that a significant increase in alcohol excise duty is necessary to achieve rapid results in reducing alcohol-attributable mortality [41,42,43]. The positive changes in life expectancy over the past fifteen years were caused by a decrease in mortality from external causes of death, cardiovascular diseases, and alcohol-induced disorders [44, 45]. Changes in mortality from external causes of death among females had a lower association with alcohol use and therefore were less influenced by ACP [44].

The WHO recommends raising alcohol taxes to an appropriate level as one of the most effective ways to reduce alcohol-attributable mortality [46]. Thus, the most effective ACP interventions, which led to an immediate change in both overall mortality and alcohol-attributable mortality, were the WHO's so-called "best buys", and were mainly driven by significant increases in alcohol excise taxes [47, 48].

Limitations

There are a few limitations of the current study that must be acknowledged. First, as mentioned above, the assessment of causality is limited due to the ecological nature of the study. Second, the alcohol-attributable mortality rate may have been reduced in individual countries because of possible ethical principles in capturing other death codes not attributable to alcohol. Third, in some of the countries assessed, the low proportion of autopsies may have caused problems in verifying the diagnosis of death and the possible causes of death associated with alcohol exposure (the percentage of autopsies in the BC decreased 2–3 times over the last two decades). Fourth, over the last two decades, it has not been possible in the countries under investigation to accurately assess compliance with ACP. Fifth, other smaller groups of alcohol-attributable deaths may have brought some changes in the assessment of alcohol-attributable mortality and coding inaccuracies (in the Polish alcohol-related mortality database, among the 22 additional alcohol-related causes of death, only ten alcohol-related cause-of-death codes were completed).

Conclusions

Alcohol-attributable mortality was significantly higher in Estonia, Latvia and Lithuania, compared with Poland. Based on the findings of the current study, alcohol control policy in the form of reduced availability and increased taxation was associated with reduced alcohol-attributable mortality among both males and females. Further studies analyzing the effect of alcohol control policies on alcohol-attributable mortality in multiple countries are needed.

Availability of data and materials

The data that support the findings of this study are not openly available due to reasons of sensitivity and are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request. Data are located in controlled access data storage at the Health Research Institute of the Lithuanian University of Health Sciences.

Abbreviations

- AAM:

-

Alcohol-attributable mortality

- ACP:

-

Alcohol control policy

- BC:

-

Baltic countries

References

WHO. Global status report on alcohol and health-2018. 2018.

Rehm J, Gmel GE, Gmel G, Hasan OSM, Imtiaz S, Popova S, et al. The relationship between different dimensions of alcohol use and the burden of disease-an update. Addict Abingdon Engl. 2017;112(6):968–1001.

Rehm J, Hasan OSM, Imtiaz S, Neufeld M. Quantifying the contribution of alcohol to cardiomyopathy: a systematic review. Alcohol. 2017;61:9–15.

Bloomfield K, Grittner U, Kramer S, Gmel G. Social inequalities in alcohol consumption and alcohol-attributable problems in the study countries of the EU concerted action “Gender, Culture and Alcohol Problems: a Multi-national Study.” Alcohol Alcohol Suppl. 2006;41:i26–36.

Ramstedt M. Population drinking and liver cirrhosis mortality: is there a link in Eastern Europe? Addiction. 2007;102(8):1212–23.

Radisauskas R, Kim KV, Lange S, Liutkute-Gumarov V, Mesceriakova-Veliuliene O, Petkeviciene J, et al. Cardiovascular diseases mortality and alcohol control policy in Lithuania: exploring a possible link. BMC Public Health. 2021;21(1):2116.

Tran A, Jiang H, Lange S, Manthey J, Štelemėkas M, Badaras R, et al. Can alcohol control policies reduce cirrhosis mortality? An interrupted time-series analysis in Lithuania. Liver Int. 2022;42(4):765–74.

Stickley A, Leinsalu M, Andreev E, Razvodovsky Y, Vagero D, McKee M. Alcohol poisoning in Russia and the countries in the European part of the former Soviet Union, 1970–2002. Eur J Public Health. 2007;17:444–9.

Stumbrys D, Štelemėkas M, Jasilionis D, Rehm J. Weekly pattern of alcohol-attributable male mortality before and after imposing limits on hours of alcohol sale in Lithuania in 2018. Scand J Public Health. 2023:14034948231184288. https://doi.org/10.1177/14034948231184288.

OECD Statistics; https://data.oecd.org/healthrisk/alcohol-consumption.htm

Alcohol, total per capita (15+) consumption (in liters of pure alcohol) (SDG Indicator 3.5.2). Available from: https://www.who.int/data/gho/data/indicators/indicator-details/GHO/total-(recorded-unrecorded)-alcohol-per-capita-(15-)-consumption

Rehm J, Tran A, Gobiņa I, et al. Do alcohol control policies have the predicted effects on consumption? An analysis of the Baltic countries and Poland 2000–2020. Drug Alcohol Depend. 2022;241:109682.

Štelemėkas M, Manthey J, Badaras R, Casswell S, Ferreira-Borges C, Kalėdienė R, et al. Alcohol control policy measures and all-cause mortality in Lithuania: an interrupted time-series analyses. Addiction. 2021;116(10):2673–84.

Global status report on alcohol and health 2018. Available from: https://www.who.int/publications-detail-redirect/9789241565639

Rehm J, Štelemėkas M, Ferreira-Borges C, Jiang H, Lange S, Neufeld M, et al. Classifying Alcohol Control Policies with Respect to Expected Changes in Consumption and Alcohol-Attributable Harm: The Example of Lithuania, 2000–2019. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2021;18:2419.

Rehm J, Lange S, Gobiņa I, Janik-Koncewicz K, Miščikienė L, Reile R, et al. Classifying alcohol control policies enacted between 2000 and 2020 in Poland and the Baltic countries to model potential impact. Addiction. 2023;118(3):449–58.

Rehm J, Badaras R, Ferreira-Borges C, Galkus L, Gostautaite Midttun N, Gobiņa I et al. Impact of the WHO "best buys" for alcohol policy on consumption and health in the Baltic countries compared to Poland 2000–2020. Lancet Regional Health – Europe, 2023; https://doi.org/10.1016/j.lanepe.2023.100704.

Miščikienė L, Midttun NG, Galkus L, Belian G, Petkevičienė J, Vaitkevičiūte J, Štelemėkas M. Review of the Lithuanian Alcohol Control Legislation in 1990–2020. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2020;17(10):3454.

Neufeld M, Ferreira-Borges C, Gil A, Manthey J, Rehm J. Alcohol policy has saved lives in the Russian Federation. Int J Drug Policy. 2020;80:102636.

Vaitkevičiūtė J, Gobiņa I, Janik-Koncewicz K, Lange S, Miščikienė L, Petkevičienė J, et al. Alcohol control policies reduce all-cause mortality in Baltic Countries and Poland between 2001 and 2020. Sci Rep. 2023;13(1):6326.

ICD-10 codes; https://icd.who.int/browse10/2019/en#/IX.

Rehm J, Baliunas D, Borges GL, Graham K, Irving H, Kehoe T, et al. The relation between different dimensions of alcohol consumption and burden of disease: an overview. Addiction. 2010;105(5):817–43.

Revision of the European Standard Population Report of Eurostat's task force; https://ec.europa.eu/eurostat/documents/3859598/5926869/KS-RA-13-028-EN.PDF/e713fa79-1add-44e8-b23d-5e8fa09b3f8f

R Core Team. R: A language and environment for statistical computing Vienna, Austria: R Foundation for Statistical Computing; 2021. [cited 2022 Aug 3]. Available from: https://www.R-project.org/

Beard E, Marsden J, Brown J, Tombor I, Stapleton J, Michie S, et al. Understanding and using time–series analyses in addiction research. Addiction. 2019;114:1866–84.

Osborne J. Notes on the use of data transformations. Pract Assess Res Eval. [cited 2022 Dec 9]; 8 (Article 6). Available from: https://scholarworks.umass.edu/pare/vol8/iss1/6/

Boisbunon A, Canu S, Fourdrinier D, Strawderman W, Wells MT. Akaike’s Information Criterion, Cp and Estimators of Loss for Elliptically Symmetric Distributions. Int Stat Rev. 2014;82(3):422–39.

Satorra A, Bentler PM. Ensuring Positiveness of the Scaled Difference Chi-square Test Statistic. Psychometrika. 2010;75(2):243–8.

Wood SN. Generalized Additive Models: An Introduction with R. Chapman and Hall/CRC Press. 2006.

Schaffer AL, Dobbins TA, Pearson SA. Interrupted time series analysis using autoregressive integrated moving average (ARIMA) models: a guide for evaluating large-scale health interventions. BMC Med Res Methodol. 2021;21(1):1–12.

Hyndman RJ. and Khandakar Y. Automatic time series forecasting: The forecast package for R. Journal of Statistical Software, 2008; 27: 1–22. https://doi.org/10.18637/jss.v027.i03

Pruckner N, Hinterbuchinger B, Fellinger M, König D, Waldhoer T, Lesch OM, et al. Alcohol-related mortality in the WHO European region: sex-specific trends and predictions. Alcohol Alcohol. 2019;54:593–8.

Degenhardt L, Charlson F, Ferrari A, Santomauro D, Erskine H, Mantilla-Herrara A, et al. The global burden of disease attributable to alcohol and drug use in 195 countries and territories, 1990–2016: a systematic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2016. Lancet Psychiatry. 2018;5(12):987–1012.

WHO. Regional Office for Europe. Making the WHO European Region SAFER: developments in alcohol control policies, 2010–2019. World Health Organization. Regional Office for Europe; 2021, 51 p. Available from: https://apps.who.int/iris/handle/10665/340727

WHO HFA-DB. Pure alcohol consumption, litres per capita, age 15+. https://gateway.euro.who.int/en/indicators/hfa_426-3050-pure-alcohol-consumption-litres-per-capita-age-15plus/visualizations/#id=19443&tab=graph.

Health Information Centre of Institute of Hygiene. Causes of death 2020. Vilnius; 2021 p. 194. Available from: https://hi.lt/uploads/pdf/leidiniai/Statistikos/Mirties_priezastys/Mirties_priezastys_2020.pdf.

Radisauskas R, Prochorskas R, Grabauskas V, Bernotiene G, Tamosiunas A, Veryga A. Recent heavy alcohol consumption at death certified as ischaemic heart disease: correcting mortality data from Kaunas (Lithuania). Alcohol Alcohol. 2011;46(5):614–9.

Erol A, Karpyak VM. Sex and gender-related differences in alcohol use and its consequences: Contemporary knowledge and future research considerations. Drug Alcohol Depend. 2015;156:1–13.

Johnson PB, Richter L, Kleber HD, McLellan AT, Carise D. Telescoping of Drinking-Related Behaviors: Gender, Racial/Ethnic, and Age Comparisons. Subst Use Misuse. 2005;40(8):1139–51.

Shadish WR, Cook TD, Campbell DT. Experimental and Quasi-experimental designs for generalized causal inference. New York, US: Houghton Mifflin Company; 2002.

Grigoriev P, Bobrova A. Alcohol control policies and mortality trends in Belarus. Drug Alcohol Rev. 2020;39(7):805–17.

Stockwell T, Churchill S, Sherk A, Sorge J, Gruenewald P. How many alcohol-attributable deaths and hospital admissions could be prevented by alternative pricing and taxation policies? Modeling impacts on alcohol consumption, revenues and related harms in Canada. Health Promot Chronic Dis Prev Can. 2020;40(5–6):153–64.

Wagenaar AC, Tobler AL, Komro KA. Effects of alcohol tax and price policies on morbidity and mortality: a systematic review. Am J Public Health. 2010;100(11):2270–8.

Grigoriev P, Jasilionis D, Stumbrys D, Stankūnienė V, Shkolnikov VM. Individual- and area-level characteristics associated with alcohol-related mortality among adult Lithuanian males: A multilevel analysis based on census-linked data. PLoS ONE. 2017;12(7):e0181622.

Stumbrys D, Telksnys T, Jasilionis D, Liutkutė Gumarov V, Galkus L, Goštautaitė-Midttun N, Štelemėkas M. Alcohol-related male mortality in the context of changing alcohol control policy in Lithuania 2000–2017. Drug Alcohol Rev. 2020;39(7):818–26.

Neufeld M, Rovira P, Ferreira-Borges C, Kilian C, Sassi F, Veryga A, Rehm J. Impact of introducing a minimum alcohol tax share in retail prices on alcohol-attributable mortality in the WHO European Region: A modeling study. Lancet Reg Health Eur. 2022;15: 100325.

WHO. ‘Best buys’ and other recommended interventions for the prevention and control of noncommunicable diseases. Updated (2021) Appendix 3 of the global action plan for the prevention and control of noncommunicable diseases 2013–2020. 2021. Available at: https://www.who.int/ncds/management/WHO_Appendix_BestBuys.pdf

Chisholm D, Moro D, Bertram M, Pretorius C, Gmel G, Shield K, Rehm J. Are the “best buys” for alcohol control still valid? An update on the comparative cost-effectiveness of alcohol control strategies at the global level. J Stud Alcohol Drugs. 2018;79(4):514–22.

Acknowledgements

This research was conducted as part of the project "Evaluation of the impact of alcohol control policies on morbidity and mortality in Lithuania and other Baltic states" and we would like to thank the whole team for their input to wider discussions in generating the research reported in this paper.

Funding

This work was supported by the National Institute on Alcohol Abuse and Alcoholism of the National Institutes of Health (NIAAA), grant number 1R01AA028224-01, and was conducted as part of the project "Evaluation of the impact of alcohol control policies on morbidity and mortality in Lithuania and other Baltic states". Content is the responsibility of the authors and does not reflect the official positions of NIAAA or the National Institutes of Health.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Ri.Ra., M.S., J.P., J.R., and H.J. completed the primary analysis and interpretation of data for this analysis and wrote the original manuscript draft. Ri.Ra., M.S., J.P., J.T., I.G., R.S., Ra.Re., K.J.K., and W.Z. contributed to data collection and manuscript writing. T.T. and H.J. performed the data analysis and prepared the Tables and Figures and wrote the methods section of the manuscript. The draft background and discussion sections were prepared by Ri.Ra., M.S., J.P., J.T., L.M., I.G., R.S., Ra.Re., K.J.K., W.Z., S.L., and A.T. Ri.Ra. wrote the first draft of the results section. All authors reviewed and approved this version of the manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

The study was conducted according to the guidelines of the Declaration of Helsinki.

All study protocols were approved by the Research Ethics Board of the Centre for Addiction and Mental Health, Institute for Mental Health Policy Research, Toronto, Canada on April 17, 2020, and renewed on March 30, 2021 (REB decision letter no. 050/2020).

The Lithuanian Bioethics Committee has confirmed that anonymized mortality data is not subject to the requirements of the Law on the Ethics of Biomedical Research in Lithuania (certificate no. 6B-17–91).

All methods were carried out in accordance with relevant guidelines and regulations.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary Information

Additional file 1: Annex 1.

Table 1S. Single-policy models for Baltic countries and Poland by sex and alcohol control policies.

Additional file 2: Annex 2.

ACF and PACF curves.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/. The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver (http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/) applies to the data made available in this article, unless otherwise stated in a credit line to the data.

About this article

Cite this article

Radišauskas, R., Štelemėkas, M., Petkevičienė, J. et al. Alcohol-attributable mortality and alcohol control policy in the Baltic Countries and Poland in 2001–2020: an interrupted time-series analysis. Subst Abuse Treat Prev Policy 18, 65 (2023). https://doi.org/10.1186/s13011-023-00574-7

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s13011-023-00574-7