Abstract

Maternal obesity is associated with significantly lower rates of breastfeeding initiation, duration and exclusivity. Increasing rates of obesity among reproductive-age women has prompted the need to carefully examine factors contributing to lower breastfeeding rates in this population. Recent research has demonstrated a significant impact of breastfeeding to reduce the risk of obesity in both mothers and their children. This article presents a review of research literature from three databases covering the years 1995 to 2014 using the search terms of breastfeeding and maternal obesity. We reviewed the existing research on contributing factors to lower breastfeeding rates among obese women, and our findings can guide the development of promising avenues to increase breastfeeding among a vulnerable population. The key findings concerned factors impacting initiation and early breastfeeding, factors impacting later breastfeeding and exclusivity, interventions to increase breastfeeding in obese women, and clinical considerations. The factors impacting early breastfeeding include mechanical factors and delayed onset of lactogenesis II and we have critically analyzed the potential contributors to these factors. The factors impacting later breastfeeding and exclusivity include hormonal imbalances, psychosocial factors, and mammary hypoplasia. Several recent interventions have sought to increase breastfeeding duration in obese women with varying levels of success and we have presented the strengths and weaknesses of these clinical trials. Clinical considerations include specific techniques that have been found to improve breastfeeding incidence and duration in obese women. Many obese women do not obtain the health benefits of exclusive breastfeeding and their children are more likely to also be overweight or obese if they are not breastfed. Further research is needed into the physiological basis for decreased breastfeeding among obese women along with effective interventions supported by rigorous clinical research to advance the care of obese reproductive age women and their children.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Data indicate that overweight and obesity among reproductive aged women has increased in the last decade and nearly 60 % of reproductive aged women in the US are overweight or obese. This contributes to the 31 % rate of overweight and obesity in US children aged 2–19 years [1–3].

Maternal pre-pregnancy obesity (Body mass index, BMI > 30) is associated with up to 13 % lower rates of breastfeeding initiation, and 20 % decreased likelihood of any breastfeeding at six months postpartum [4–15]. Breastfeeding has a dose-response-like effect to reduce the risk of childhood obesity by as much as 32 %, and significantly reduces the risk of obesity-associated co- morbidities such as diabetes, high blood pressure and elevated cholesterol in both mothers and their breastfed children [16–23]. Yet obese mothers are among the least likely to breastfeed as long or as exclusively as recommended [17, 19]. Dramatic differences exist in breastfeeding rates between countries and cultures; however there appears to be a significant effect of maternal obesity to reduce both breastfeeding initiation and duration independent of nation of study [24–34]. In the United States, studies have demonstrated between 7 and 13 % decreases in breastfeeding incidence among obese women [35–37]. Similarly, the Longitudinal Study of Australian Children [14] demonstrated that obese Australian women were 8 % less likely to initiate breastfeeding, and that increasing body mass index (BMI) over 30 had a dose-response-like effect to reduce breastfeeding incidence. Among those who initiated breastfeeding, obese mothers were 7 % less likely to continue breastfeeding to one week and almost 13 % less likely to be breastfeeding at six months [14]. A 2007 study in Danish women also demonstrated a dose-response-type of relationship between increasing BMI > 30 and lower incidence of breastfeeding [38]. Finding this association in societies that are supportive of breastfeeding (Denmark and Australia) suggests that socio-cultural issues may not be a major cause of decreased breastfeeding initiation in obese women [39, 40]. Even among those with known medical conditions (diabetes, pre-eclampsia) associated with lower breastfeeding rates, maternal obesity further increases the risk of early breastfeeding cessation [41–45].

Our objectives for this review were to summarize the existing research on potential causes of reduced breastfeeding incidence, exclusivity and duration in obese women, present the results of the existing breastfeeding interventions in this population, and discuss clinical considerations of relevance and future directions for research.

Methods

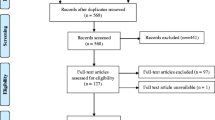

We performed a literature search of Web of Science, PubMed (Medline), and the Cochrane database with the search terms “breastfeeding” and “maternal obesity” from 1995 to August 2014, restricted to English (PubMed, Web of Science) and humans (PubMed) (see Fig. 1) [46]. Criteria for inclusion were peer reviewed original research reporting on breastfeeding initiation, exclusivity or duration, or factors related to breastfeeding initiation, exclusivity or duration in obese mothers (BMI ≥ 30) of term infants (37–42 weeks gestation). Authors screened abstracts with these criteria, and then accessed full text articles. From the full text articles, five meeting abstracts were removed, as were two articles with definitions of obesity that included groups categorized by the World Health Organization as overweight (BMI ≥26), and one article focusing on weight retention in obese mothers in relation to breastfeeding. The references of chosen articles and the authors’ libraries were also hand searched for relevant studies. Articles reporting only on obesity as a risk factor for non-initiation or early cessation of breastfeeding are incorporated into the article introduction. Those reporting on interventions or factors relating to breastfeeding outcomes in obese women are included in the body of the review.

Review

Factors impacting early breastfeeding

Mechanical factors/edema

Mechanical factors, such as additional body tissue, larger areolas and larger breasts that reduce lap area have often been cited as an impediment to breastfeeding in obese women [6, 7, 9, 40, 47, 48]. Despite the frequency of this suggestion, we found no published studies documenting a significant impact of mechanical factors on breastfeeding in obese mothers. There is evidence, however, that obese women are more likely to experience significant postpartum edema [12].

This can result in pooling of the fluid load in the breasts, flattening the nipples and making latch more difficult. Beyond this, some, although not all, obese women may be more likely to have larger breasts, which can make traditional breastfeeding positions more challenging [47].

Delayed onset of lactogenesis II

Lactogenesis II, or the onset of copious milk production, is triggered by transcription of prolactin-responsive genes following removal of placental progesterone [49]. For most mothers, lactogenesis II occurs within 72 h postpartum. Studies have demonstrated that maternal obesity is associated with delays in the onset of lactogenesis II (DOL) which can reduce the mother’s confidence that her milk is sufficient for her child, lead to early introduction of breast milk substitutes, and result in early cessation of breastfeeding [48]. A small observational study in a Swiss hospital found that obese mothers were more likely to use “breastfeeding aids” such as bottles, cups and maltodextrin supplementation [50], and this observation is consistent with the findings of larger studies indicating that obese mothers are less likely to be exclusively breastfeeding at hospital discharge, even among those who intend to breastfeed exclusively [51].

Research suggests that DOL in obese women may be due to several factors. Obesity increases the risk of significant postpartum edema, which is independently associated with DOL [12]. Obese mothers also have an increased incidence of longer and dysfunctional labor and higher rates of cesarean birth, which are also associated with DOL [52]. Moynihan et al. have suggested that the increase in dysfunctional labor and cesarean birth in obese mothers may be linked to a leptin-dependent blunting of oxytocin stimulated muscle contraction [53]. Leptin, an adipokine, is secreted by adipose tissue, and leptin levels increase with increasing BMI. In vitro, leptin inhibits oxytocin’s effect on muscle contractions, potentially contributing to increases in labor dysfunction observed in obese women [53]. As oxytocin is also necessary for the milk ejection reflex, elevated leptin levels in obese women may negatively influence milk availability. In addition, Rasmussen and Kjolhede showed in 2004 that obese women have reduced baseline levels of prolactin in the first 48 h postpartum, and reduced suckling-induced release of prolactin at 2–7 days postpartum, which may reduce the rate of milk synthesis during this time [54, 55]. Interestingly, Kitsantas and Pawloski found that obese mothers with no medical or labor complications were as likely to initiate breastfeeding as non-obese mothers, although they were 11 % more likely to stop breastfeeding each month thereafter [13]. As lactogenesis II generally occurs 24–72 h after birth and breastfeeding initiation, this finding is not inconsistent with observed delays in the onset of lactogenesis in obese mothers.

Several studies now suggest that insulin is required for lactogenesis II and an imbalance in insulin may directly influence the timing of lactogenesis II. Obese women have a less steep decline in insulin concentrations from the end of pregnancy to the initiation of lactation, perhaps leading to less glucose available for milk synthesis [56]. Nommsen-Rivers, Dolan, and Huang recently found that the insulin/glucose ratio measured at 26 weeks of gestation could predict the timing of lactogenesis II [57]. Similarly, RNA sequencing of the human milk fat layer demonstrated increased expression of protein tyrosine phosphatase receptor type F, a phosphatase known to down-regulate insulin signaling in a group of mothers with DOL [58].

Each of these factors may contribute to DOL in obese women.

Factors impacting longer breastfeeding duration and exclusivity in obese women

Androgens

In addition to alterations in prolactin and insulin, free androgens also increase with increasing BMI in women [59]. A recent study by Carlsen et al. found a negative correlation between mid-pregnancy androgen levels and breastfeeding duration at 3 and 6 months [60]. Some data also indicate that polycystic ovarian syndrome (PCOS) may play a role in reducing breastfeeding duration and exclusivity in obese women [61, 62]. PCOS is associated with elevated androgens, metabolic abnormalities and hypothyroidism, and PCOS often occurs alongside overweight or obesity [63]. A 2008 study by Vanky et al. found that in the first month of lactation mothers with PCOS were less likely to be exclusively breastfeeding [64]. The authors suggested this difference might be due to slightly elevated 3rd trimester levels of the androgen Dehydroepiandrosterone (DHEA) in mothers with PCOS [64].

Thyroid dysfunction

Obesity and overweight may result from subclinical and overt hypothyroidism, the symptoms of which (fatigue, weight gain, hair loss) may be dismissed as normal postpartum complaints [65]. Animal models have demonstrated the requirement for levothyroxine (T4) and liothyronine (T3) in initiation and maintenance of lactation, and human mothers with suboptimal levels may have lower milk supply and reduced oxytocin release in response to suckling [66].

Treatment with levothyroxine to bring maternal T4 and thyroid stimulating hormone (TSH) levels within normal range generally alleviates the problems hypothyroidism presents to lactation [67]. Multiple sources now recommend that serum TSH levels between 0.5 and 2.5 are optimal for pregnancy and perhaps lactation as well [68, 69].

Psychosocial factors

Several studies have linked obesity to psychosocial factors that independently reduce breastfeeding initiation, exclusivity and duration. In their 2014 study of 2824 American participants in the Infant Feeding Practices Study II (IFPSII), Hauff, Leonard and Rasmussen found that obese women demonstrated reduced confidence in their ability to reach their own breastfeeding goals (p < 0.0001), fewer close friends and relatives who had breastfed (p < 0.0001), and lower social influence to breastfeed (p < 0.02) [70]. Obese mothers in this study did not have reduced intention to breastfeed, but did have lower odds of ever breastfeeding, and were at greater risk of early breastfeeding discontinuation [70]. This finding agrees with that of Kronberg, Vaeth and Rasmussen, who found maternal obesity to be associated with lower maternal self-efficacy and a higher rate of early breastfeeding cessation in a study of 1597 Danish mothers [71]. In their study of 233 overweight and obese women, Hauff and Demerath reported obese women with body image concerns had a lower median duration of breastfeeding than normal weight women without body image concerns (38.6 weeks v 48.9 weeks, respectively; p = 0.01) [40]. The authors also reported the probability of obese women to breastfeed at six months at 66 % in comparison to 80 % for normal weight women [40]. They suggest that discomfort with their bodies may cause obese women to be hesitant to breastfeed [40]. By contrast, Zanardo et al. found that Italian obese mothers in a case-control study had higher scores on Eating Disorders Inventory (EDI-2) measures such as body dissatisfaction (p < 0.001), but were significantly less likely than non-obese mothers to stop breastfeeding before six months [71]. Another study with the same population found that the obese mothers were also more likely to report body image dissatisfaction [72]. Foster et al. reported in 1996 that women who intended to bottle feed had higher levels of body dissatisfaction (median 47.5 v 38.5, p = 0.004) and higher expressed concerns about shape/weight (median 1.05 v 0.29, p = 0.02) than those who intended to breastfeed, however, breastfeeding intention was not correlated with BMI in this small study [73]. Krause et al. found that unrealistic expectation of the effect of breastfeeding to reduce maternal weight may negatively impact breastfeeding duration among overweight and obese mothers [74].

Although most studies have found an independent association between maternal obesity and reduced breastfeeding incidence and duration, some have found sociodemographic characteristics to be more significant. In a prospective cohort study of 718 women in Hershey Pennsylvania, Bartok et al. found that obese mothers had a shorter duration of providing breast milk and an earlier introduction of formula than non-obese mothers. However, when the authors controlled for confounding variables, the association with BMI disappeared, and only education, marital status, planned breastfeeding duration, and rating of breastfeeding importance significantly impacted breastfeeding duration [75]. In addition, studies have not found maternal obesity to have a significant impact on breastfeeding incidence and duration in African American women [8, 37]. This finding may be related to low baseline levels of breastfeeding incidence in the African American population in general [76].

Mammary hypoplasia/insufficient glandular tissue

Some evidence from research in dairy cows and mice suggests that obesity in early life may negatively impact breast glandular development [77, 78]. This may put obese mothers at risk of insufficient glandular tissue and/or mammary hypoplasia [78, 79]. For example, a study of dairy cows fed a high energy diet during puberty demonstrated increased mammary adipose tissue and reduced mammary epithelium in adulthood [77]. Obese mice also show reductions in mammary gland development and the milk proteins β casein, whey acidic protein, and αlactalbumin, which are essential for milk production [78]. Classic markers for mammary hypoplasia in humans are wide intramammary space, breast asymmetry, stretch marks, and little or no breast growth in pregnancy [79]. However, insufficient glandular tissue may also be present without these physical characteristics [80]. In agreement with findings in animals, obese mothers are more likely to report characteristics consistent with insufficient milk supply than are non-obese mothers [81]. Mok et al. found that only 60 % of obese women perceived their milk supply to be adequate at one month postpartum compared with 94 % of normal weight controls [81]. Obese women are almost twice as likely to indicate they stopped breastfeeding due to insufficient milk (24 % vs. 13 %), and women with higher BMI report insufficient milk earlier than women with BMI in the normal range [82, 83]. In a study of breast milk expression using a breast pump or hand expression in the first two months postpartum, obese women were more likely to try to express milk, but less likely to be successful [84]. The significantly lower rate of exclusive breastfeeding among obese women also suggests obese mothers may feel they do not make sufficient breast milk to feed their babies, and need to supplement the infant’s diet to provide adequate calories [10, 81–83, 85]. Interestingly, in an analysis of IFPSII data, Leonard et al. found that the tendency of women with higher BMI to deliver heavier infants actually underestimates the magnitude of the negative impact of maternal obesity on breastfeeding duration, as heavier infants are breastfed for longer duration in the general population [86]. This may partially explain the unusual results of a retrospective cohort study in Ontario which found that mothers with Class III obesity (n = 249, BMI ≥ 40), who were significantly more likely to give birth to a baby that was large for gestational age (LGA), were as likely to initiate breastfeeding and be breastfeeding at hospital discharge as mothers with normal BMI (n = 446, BMI 18.5–24.9) [87].

Interventions to increase breastfeeding in obese women

In contrast to the many interventions conducted to increase breastfeeding in the general population, only four published interventions have focused on increasing breastfeeding duration and exclusivity specifically in obese women (see Table 1). The first two, published in 2011 by Rasmussen et al., were conducted in parallel based in rural Bassett Hospital in New York, called the Bassett Improving Breastfeeding Studies (BIBS) 1 and 2 [88]. The BIBS1 study protocol called for the intervention group (n = 19) to receive three telephone calls by one of three International Board Certified Lactation Consultants (IBCLC), one call prenatally and then at 48 and 72 h to educate, assist with and encourage breastfeeding. Mothers in the control group (n = 20) were also given a less detailed prenatal call. BIBS1 was poorly executed in that only 11 mothers in each of the control and intervention groups received the appropriate interventions.

Baseline data indicated that the intervention and control groups were non-equivalent in BMI at delivery. When adjusted for BMI at delivery, logistic regression found the probability of any breastfeeding at 30 days was significantly less in the intervention group (p < 0.04), and any breastfeeding was highly correlated with BMI at delivery at 90 days (p < 0.03) [88].

BIBS2 looked at the impact of the provision of a breast pump on breastfeeding duration in a similar population. Intervention group mothers were given a single manual or multiuser double electric breast pump and instructed to pump for 10 min after each of five breastfeeding sessions each 24 h for five days or until their milk came in [88]. When compared with the control group and analyzed as intent to treat, mothers given a pump breastfed for significantly shorter duration [88]. There were significant challenges in this study as well, as many mothers in the control group used a pump, and mothers in the intervention group used their own rather than a study pump [88]. When controlled for type of pump used, there was no difference in breastfeeding duration between mothers who used a manual or an electric pump [88]. Further analysis revealed that BMI at delivery was significantly associated with shorter breastfeeding at the 30 day time point (p < 0.03) [88]. When BMI at delivery was added to the logistic regression model, the differences in breastfeeding duration between pumping and control groups were no longer significant [88]. The lack of stratification for obesity and small sample size of both BIBS1 (n = 40) and BIBS2 (n = 39) limit the usefulness of these studies in designing future interventions [88].

From 2006–2009, Chapman et al. conducted a randomized controlled trial using breastfeeding education and support provided both in person and by phone by peer counselors [89]. Two hundred and six low income overweight and obese women (BMI ≥ 27) who delivered in a Baby Friendly Hospital in Connecticut were randomized to either a control group which included three prenatal visits, phone access, daily in hospital support, and up to seven home visits from a breastfeeding peer counselor, or an intervention group which included three prenatal visits, daily in-hospital support, and up to 11 postpartum home visits from a specialized breastfeeding peer counselor who had 20 h of obesity-specific breastfeeding training [89]. The intervention group did not demonstrate a significant increase in breastfeeding duration or exclusivity at 1, 3 or 6 months. Further analysis showed that at two weeks postpartum, mothers in the intervention had greater odds of continuing any breastfeeding (adjusted odds ratio (AOR) 3.76; 95 % confidence interval (CI): 1.07, 13.22), and of giving at least 50 % of feeding as breast milk (AOR 4.47; 95 % CI: 1.38, 14.5) [89]. Infants of intervention mothers were also less likely to be hospitalized during the first six months of age (AOR 0.24; 95 % CI: 0.07, 0.86) [89]. The authors suggest that the limited effects on breastfeeding duration seen with this population may be due to the fact that mothers in the control group were already receiving a significant amount of breastfeeding support [89].

The most recent intervention study provided breastfeeding support via phone calls by an International Board-Certified Lactation Consultant (IBCLC) [90]. The study by Carlsen et al. included 207 obese (BMI ≥ 30) women delivering singleton infants in Hvidovre Hospital in Copenhagen, Denmark who were participating in the Treatment of Obese Pregnant Study (TOPS) to reduce weight gain during pregnancy (gestational weight gain goal < 5 kg) [90].

Mothers in the TOPS study had been assigned to one of 3 groups: 1) exercise alone, 2) exercise and diet, or 3) control [90]. Mothers and their newborns were consecutively recruited into the breastfeeding support intervention without regard to their TOPS study group, allocated into the breastfeeding support intervention or control group [90]. Mothers in the support intervention (n = 105) were offered a minimum of nine telephone consultations by a single IBCLC during the first six months so long as they continued to breastfeed [90]. The initial contact was made within the first week postpartum, and two more contacts were made that month, followed by phone calls every two weeks until eight weeks, then monthly until six months [90]. Extra calls were made for specific difficulties, and all mothers in the intervention group had the direct telephone number to the study IBCLC, available seven days per week [90]. Mothers in the control group (n = 102) had access to usual care, which included contact with a breastfeeding supportive pediatric nurse within one week of birth, and standard breastfeeding support at the study hospital [90]. Both groups were equivalent in BMI prenatally [90]. In contrast to previous studies discussed above, provision of phone call support in this intervention significantly increased breastfeeding duration and exclusivity [90]. Mothers in the intervention group breastfed exclusively for a median of 120 days (25th–75th percentiles: 14–142 days) compared with 41 days for control mothers (3–133 days, p = 0.003) [90]. Those given the support intervention also had increased duration of any breastfeeding (median 184 days (92–185 days) compared with those in the control group (median 108 days (16–185 days) p = 0.002) [90]. Support increased the adjusted odds ratio for exclusive breastfeeding at three months (AOR 2.45; 95 % CI: 1.36, 4.41; p = 0.003) and partial breastfeeding at six months (OR 2.25; 95 % CI: 1.24, 4.08; p = 0.008) [90]. An impact on breastfeeding duration was evident even before the phone calls began, indicating that the Hawthorne effect may have played a role [90, 91].

It is of interest that this most recent support intervention [90] resulted in increased breastfeeding duration and exclusivity, in contrast to previous support interventions in obese mothers [89, 90]. As the execution and design of the BIBS studies were flawed, we cannot use them to draw accurate conclusions; however, both Carlsen et al. and Chapman et al. delivered a support intervention to obese mothers [88–90]. Several key differences between these two studies may have impacted the outcome. First, the populations studied were quite dissimilar. Chapman et al. was conducted with a group of low income, > 80 % Latina mothers in the United States, while the Carlsen et al. population was comprised of a group of Danish mothers of unknown socioeconomic status or ethnicity who were already participating in a study to reduce weight gain in pregnancy [89, 90]. The mothers in the Carlsen et al. study had received education about adiposity and healthy lifestyle during pregnancy, and were likely already highly motivated [90]. In addition to differences in ethnicity, socioeconomic status and participation in another lifestyle intervention, the mothers in the Carlsen et al. study were an average of eight years older, and had two years more education than those in the Chapman et al. study [89, 90]. Socioeconomic status, age, and years of education have all been shown to have significant effects on breastfeeding duration and exclusivity [92, 93]. Denmark also provides a full 52 weeks of maternity leave to employed mothers, while the more than 30 % of mothers employed prenatally in the Chapman et al. study may have had access to little or no maternity leave [89, 90]. In the larger (non-obese) population, support interventions have shown an increased treatment effect on exclusive breastfeeding in areas where background breastfeeding rates are high [94]. Breastfeeding initiation, duration, and exclusivity are significantly higher in Denmark than in the US, which may have increased the effectiveness of the support intervention on this outcome measure [95].

The interventions themselves also differed in several ways that may have impacted the study outcome. The Chapman et al. study began prenatally while Carlsen et al. began at three days postpartum [89, 90]. All of the interactions in the Carlsen et al. study were by phone, versus a mixture of phone and in person visits in the Chapman et al. study. This is of interest as a 2012 Cochrane review on breastfeeding support interventions concluded that regular scheduled support was more effective at increasing breastfeeding duration and exclusivity than support that required mothers to ask for help [94]. The design of the Carlsen et al. study included 7 phone calls at regularly scheduled intervals, which may have been easier to implement on a predictable schedule for mothers. In addition, the Carlsen et al. study used a single IBCLC to deliver all contacts, while the Chapman et al. study used multiple peer counselors [89, 90]. The use of a single support person for all mothers rather than multiple contacts with varying communication styles, counseling skills and personal breastfeeding experience may have increased the fidelity of the intervention.

Clinical considerations

Many clinicians are unaware of research showing that obese women have lower rates of breastfeeding or of the proposed causes [54]. Our efforts to help obese mothers reach their breastfeeding goals are limited both by an incomplete knowledge of the biological factors that may impact breastfeeding success in obese women, and by the small number of interventions targeting this population. In Table 2, we have provided some clinical considerations to be aware of when helping obese mothers to breastfeed.

Future direction

Carlsen et al.’s intervention methods led to an increase in breastfeeding duration and exclusivity in a population of older, educated Danish mothers [90]. Future studies should work to reproduce and fine tune this intervention in other populations of obese mothers, including those with lower background breastfeeding rates than those observed in Denmark. As the authors point out, although their intervention did significantly increase rates of breastfeeding in obese women, a full 15 % of the obese women in the intervention group did not successfully establish breastfeeding, and an even larger percentage did not establish exclusive breastfeeding, far below the rates of non-obese Danish women. This suggests that there may be another, perhaps physiological component that is not modifiable by support interventions. Many aspects of lactation are hormonally controlled. As obesity has been shown to alter levels and action of a large number of hormones, tracking the levels and activity of hormones known to impact lactation (such as prolactin, thyroid hormone, TSH, androgens, leptin and insulin) along with breastfeeding status at several time points postpartum in obese mothers may provide us with critical information. Animal studies also suggest that overfeeding during puberty may impair normal glandular development. A study evaluating the incidence of markers of insufficient glandular tissue/breast hypoplasia in obese mothers would be a potential first step in investigating a role for maternal obesity in impaired glandular development in humans. Given the impact of breastfeeding on both infant and maternal health, it is of critical importance that we focus future research on improving breastfeeding rates in this population.

Conclusions

Obesity is a major risk factor for reduced initiation, duration and exclusivity of breastfeeding. We concluded that much of the evidence at this stage points to physiological factors such as difficult birth, delayed onset of lactogenesis II, and imbalances of hormones and adipokines as likely contributors to lower breastfeeding rates in obese women. Although we found four published breastfeeding interventions in this population, only a single intervention providing scheduled support by an IBCLC has shown a significant effect to increase breastfeeding duration and exclusivity in obese mothers. Further research is needed to identify modifiable behavioral and physiological variables that may lead to increased breastfeeding exclusivity and duration in obese mothers.

Abbreviations

- BMI:

-

Body mass index

- DOL:

-

Delayed onset of lactogenesis II

- PCOS:

-

Polycystic ovarian syndrome

- T4:

-

Levothyroxine

- TSH:

-

Thyroid stimulating hormone

- BIBS:

-

Bassett improving breastfeeding studies

- IBCLC:

-

International Board Certified Lactation Consultant

References

Ogden CL, Carroll MD, Flegal KM. Prevalence of obesity and trends in body mass index among us children and adolescents, 1999–2010. JAMA. 2012;307(5):483–90.

Hillemeier MM, Weisman CS, Chuang C, Downs DS, McCall-Hosenfeld J, Camacho F. Transition to overweight or obesity among women of reproductive age. J Womens Health. 2011;20(5):703–10.

Flegal KM, Carroll MD, Ogden CL, Curtin LR. Prevalence and trends in obesity among us adults, 1999–2008. JAMA. 2010;303(3):235–41.

Wojcicki JM. Maternal prepregnancy body mass index and initiation and duration of breastfeeding: a review of the literature. J Womens Health. 2011;20(3):341–7.

Jevitt C, Hernandez I, Groer M. Lactation complicated by overweight and obesity: supporting the mother and newborn. J Midwifery Womens Health. 2007;52(6):606–13.

Donath SM, Amir LH. Does maternal obesity adversely affect breastfeeding initiation and duration? J Peadiatr Child Health. 2000;36(5):482–6.

Hilson JA, Rasmussen KM, Kjolhede CL. Maternal obesity and breast-feeding success in a rural population of white women. Am J Clin Nutr. 1997;66(6):1371–8.

Kugyelka JG, Rasmussen KM, Frongillo EA. Maternal obesity is negatively associated with breastfeeding success among Hispanic but not black women. J Nutr. 2004;134(7):1746–53.

Li R, Jewell S, Grummer-Strawn L. Maternal obesity and breast-feeding practices. Am J Clin Nutr. 2003;77(4):931–6.

Hilson JA, Rasmussen KM, Kjolhede CL. High prepregnant body mass index is associated with poor lactation outcomes among white, rural women independent of psychosocial and demographic correlates. J Hum Lact. 2004;20(1):18–29.

Turcksin R, Bel S, Galjaard S, Devlieger R. Maternal obesity and breastfeeding intention, initiation, intensity and duration: a systematic review. Matern Child Nutr. 2012;10(2):166–83.

Nommsen-Rivers LA, Chantry CJ, Peerson JM, Cohen RJ, Dewey KG. Delayed onset of lactogenesis among first-time mothers is related to maternal obesity and factors associated with ineffective breastfeeding. Am J Clin Nutr. 2010;92(3):574–84.

Kitsantas P, Pawloski LR. Maternal obesity, health status during pregnancy, and breastfeeding initiation and duration. J Matern Fetal Neonatal Med. 2010;23(2):135–41.

Donath SM, Amir LH. Maternal obesity and initiation and duration of breastfeeding: data from the longitudinal study of Australian children. Matern Child Nutr. 2008;4(3):163–70.

Oddy WH, Li J, Landsborough L, Kendall GE, Henderson S, Downie J. The association of maternal overweight and obesity with breastfeeding duration. J Pediatr. 2006;149(2):185–91.

Arenz S, Ruckerl R, Koletzko B, von Kries R. Breast-feeding and childhood obesity–a systematic review. Int J Obes Relat Metab Disord. 2004;28(10):1247–56.

U.S. Department of Health and Human Services. The Surgeon General’s call to action to support breastfeeding. Washington, DC: U.S: Department of Health and Human Services, Office of the Surgeon General; 2011.

Ip S, Chung M, Raman G, Chew P, Magula N, DeVine D, et al. Breastfeeding and maternal and infant health outcomes in developed countries. Evidence Report/Technology Assessment No. 153 (Prepared by Tufts-New England Medical Center Evidence-based Practice Center, under Contract No. 290-02-0022). AHRQ Publication No. 07-E007. Rockville, MD: AHRQ; 2007.

Institute of Medicine of the National Academies. Early childhood obesity prevention policies: goals, recommendations and potential actions. Washington, D.C: Institution of Medicine; 2011.

Hatsu IEMD, Anderson AK. Effect of infant feeding on maternal body composition. Int Breastfeed J. 2008;3:18.

Baker JL, Gamborg M, Heitmann BL, Lissner L, Sorensen TI, Rasmussen KM. Breastfeeding reduces postpartum weight retention. Am J Clin Nutr. 2008;88(6):1543–51.

Dewey KG. Impact of breastfeeding on maternal nutritional status. Adv Exp Med Biol. 2004;554:91–100.

Natland ST, Nilsen TI, Midthjell K, Andersen LF, Forsmo S. Lactation and cardiovascular risk factors in mothers in a population-based study: the HUNT- study. Int Breastfeed J. 2012;7:8.

Thompson LA, Zhang S, Black E, Das R, Ryngaert M, Sullivan S, et al. The association of maternal pre-pregnancy body mass index with breastfeeding initiation. Matern Child Health J. 2013;17(10):1842–51.

Plewma P. Prevalence and factors influencing exclusive breast-feeding in Rajavithi Hospital. J Med Asooc Thai. 2013;96 Suppl 3:S94–9.

Visram H, Finkelstein SA, Feig D, Walker M, Yasseen A, Tu X, et al. Breastfeeding intention and early post-partum practices among overweight and obese women in Ontario: a selective population-based cohort study. J Matern Fetal Neonatal Med. 2013;26(6):611–5.

Kronborg H, Vaeth M, Rasmussen KM. Obesity and early cessation of breastfeeding in Denmark. Eur J Public Health. 2013;23(2):316–22.

Manios Y, Grammatikaki E, Kondaki K, Ioannou E, Anastasiadou A, Birbilis M. The effect of maternal obesity on initiation and duration of breast-feeding in Greece: the GENESIS study. Public Health Nutr. 2009;12(4):517–24.

Donath SM, Amir LH. Does maternal obesity adversely affect breastfeeding initiation and duration? Breastfeed Rev. 2000;8(3):29–33.

Nohr EA, Timpson NJ, Andersen CS, Smith GD, Olsen J, Sørensen TIA. Severe obesity in young women and reproductive health: the Danish national birth cohort. PLoS One. 2009;4(12), e8444.

Kehler HL, Chaput KH, Tough SC. Risk factors for cessation of breastfeeding prior to six months postpartum among a community sample of women in Calgary, Alberta. Can J Public Health. 2009;100(5):376–80.

Sebire NJ, Jolly M, Harris JP, Wadsworth J, Joffe M, Beard RW, et al. Maternal obesity and pregnancy outcome: a study of 287 213 pregnancies in London. Int J Obes Relat Metab Disord. 2001;25(8):1174–82.

Jain NJ, Denk CE, Kruse LK, Dandolu V. Maternal obesity: can pregnancy weight gain modify risk of selected adverse pregnancy outcomes? Am J Perinatol. 2007;24(5):291–8.

Ahluwalia IB, Morrow B, Hsia J. Why do women stop breastfeeding? Findings from the pregnancy risk assessment and monitoring system. Pediatrics. 2005;116(6):1408–12.

Li R, Ogden C, Ballew C, Gillespie C, Grummer-Strawn L. Prevalence of exclusive breastfeeding among US infants: the third National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey (Phase II, 1991–1994). Am J Public Health. 2002;92(7):1107–10.

Hilson JA, Rasmussen KM, Kjolhede CL. Excessive weight gain during pregnancy is associated with earlier termination of breast-feeding among white women. J Nutr. 2006;136(1):140–6.

Liu J, Smith MG, Dobre MA, Ferguson JE. Maternal obesity and breast-feeding practices among white and black women. Obesity (Silver Spring). 2010;18(1):175–82.

Baker JL, Michaelsen KF, Sorensen TI, Rasmussen KM. High prepregnant body mass index is associated with early termination of full and any breastfeeding in Danish women. Am J Clin Nutr. 2007;86(2):404–11.

Mehta UJ, Siega-Riz AM, Herring AH, Adair LS, Bentley ME. Maternal obesity, psychological factors, and breastfeeding initiation. Breastfeed Med. 2011;6(6):369–76.

Hauff LE, Demerath EW. Body image concerns and reduced breastfeeding duration in primiparous overweight and obese women. Am J Hum Biol. 2012;24(3):339–49.

Soltani H, Arden M. Factors associated with breastfeeding up to 6 months postpartum in mothers with diabetes. J Obstet Gynecol Neonatal Nurs. 2009;38(5):586–94.

Youngwanichsetha S. Factors related to exclusive breastfeeding among postpartum Thai women with a history of gestational diabetes mellitus. J Reprod Infant Psychol. 2013;31(2):208–17.

Matias SL, Dewey KG, Quesenberry Jr CP, Gunderson EP. Maternal prepregnancy obesity and insulin treatment during pregnancy are independently associated with delayed lactogenesis in women with recent gestational diabetes mellitus. Am J Clin Nutr. 2014;99(1):115–21.

Cordero L, Valentine CJ, Samuels P, Giannone PJ, Nankervis CA. Breastfeeding in women with severe preeclampsia. Breastfeed Med. 2012;7(6):457–63.

Cordero L, Gabbe SG, Landon MB, Nankervis CA. Breastfeeding initiation in women with gestational diabetes mellitus. J Neonatal Perinatal Med. 2013;6(4):303–10.

Moher D, Liberati A, Tetzlaff J, Altman DG, The PRISMA Group (2009). Preferred reporting items for systematic reviews and meta-analyses: the PRISMA statement. Open Med. 2009;3(3):123–30.

Katz KA, Nilsson I, Rasmussen KM. Danish health care providers’ perception of breastfeeding difficulty experienced by women who are obese, have large breasts, or both. J Hum Lact. 2010;26(2):138–47.

Chapman DJ, Perez-Escamilla R. Identification of risk factors for delayed onset of lactation. J Am Diet Assoc. 1999;99(4):450–4.

Prime DK, Geddes DT, Hartmann PE. Oxytocin: milk ejection and maternal-infant well-being. In: Hale T, Hartmann PE, editors. Textbook of Human Lactation. 1st ed. Amarillo: Hale Publishing; 2007. p. 141–58.

Gubler T, Krähenmann F, Roos M, Zimmermann R, Ochsenbein-Kölble N. Determinants of successful breastfeeding initiation in healthy term singletons: a Swiss university hospital observational study. J Perinat Med. 2013;41(3):331–9.

Perrine CG, Scanlon KS, Li R, Odom E, Grummer-Strawn LM. Baby-friendly hospital practices and meeting exclusive breastfeeding intention. Pediatrics. 2012;130(1):54–60.

Bogaerts A, Witters I, Van den Bergh BRH, Jans G, Devlieger R. Obesity in pregnancy: altered onset and progression of labour. Midwifery. 2013;29(12):1303–13.

Moynihan AT, Hehir MP, Glavey SV, Smith TJ, Morrison JJ. Inhibitory effect of leptin on human uterine contractility in vitro. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2006;195(2):504–9.

Rasmussen KM, Kjolhede CL. Prepregnant overweight and obesity diminish the prolactin response to suckling in the first week postpartum. Pediatrics. 2004;113(5):e465–71.

Rasmussen KM. Association of maternal obesity before conception with poor lactation performance. Annu Rev Nutr. 2007;27(1):103–21.

Lovelady CA. Is maternal obesity a cause of poor lactation performance. Nutr Rev. 2005;63(10):352–5.

Nommsen-Rivers LA, Dolan L, Huang B. Timing of stage II lactogenesis is predicted by antenatal metabolic health in a cohort of primiparas. Breastfeed Med. 2012;7(1):43–9.

Lemay DG, Ballard OA, Hughes MA, Morrow AL, Horseman ND, Nommsen-Rivers LA. RNA sequencing of the human milk fat layer transcriptome reveals distinct gene expression profiles at three stages of lactation. PLoS One. 2013;8(7), e67531.

Michalakis K, Mintziori G, Kaprara A, Tarlatzis BC, Goulis DG. The complex interaction between obesity, metabolic syndrome and reproductive axis: a narrative review. Metabolism. 2013;62(4):457–78.

Carlsen SM, Jacobsen G, Vanky E. Mid-pregnancy androgen levels are negatively associated with breastfeeding. Acta Obstet Gynecol Scand. 2010;89(1):87–94.

West D, Marasco L. Is it your hormones? In: West D, Marasco L, editors. The Breastfeeding Mother’s Guide to Making More Milk. New York: McGraw Hill; 2009. p. 133–6.

Marasco L, Marmet C, Shell E. Polycystic ovary syndrome: a connection to insufficient milk supply? J Hum Lact. 2000;16(2):143–8.

Sridhar G, Nagamani G. Hypothyroidism presenting with polycystic ovary syndrome. J Assoc Physicians India. 1993;41(2):88–90.

Vanky E, Isaksen H, Moen MH, Carlsen SM. Breastfeeding in polycystic ovary syndrome. Acta Obstet Gynecol Scand. 2008;87(5):531–5.

Åsvold BO, Bjøro T, Vatten LJ. Association of serum TSH with high nody mass differs between smokers and never-smokers. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2009;94(12):5023–7.

Hapon MB, Simoncini M, Via G, Jahn GA. Effect of hypothyroidism on hormone profiles in virgin, pregnant and lactating rats, and on lactation. Reproduction. 2003;126(3):371–82.

Speller E, Brodribb W, McGuire E. Breastfeeding and thyroid disease: a literature review. Breastfeed Rev. 2012;20(2):41–7.

Carney LA, Quinlan JD, West JM. Thyroid disease in pregnancy. Am Fam Physician. 2014;89(4):273–8.

Stagnaro-Green A, Abalovich M, Alexander E, Azizi F, Mestman J, Negro R, et al. Guidelines of the American Thyroid Association for the diagnosis and management of thyroid disease during pregnancy and postpartum. Thyroid. 2011;1(10):1081–125.

Hauff LE, Leonard SA, Rasmussen KM. Associations of maternal obesity and psychosocial factors with breastfeeding intention, initiation, and duration. Am J Clin Nutr. 2014;99(3):624–34.

Zanardo V, Straface G, Benevento B, Gambina I, Cavallin F, Trevisanuto D. Symptoms of eating disorders and feeding practices in obese mothers. Early Hum Dev. 2014;90(2):93–6.

Zanardo V, Gambina I, Nicoló ME, Giustardi A, Cavallin F, Straface G, et al. Body image and breastfeeding practices in obese mothers. Eat Weight Disord. 2014;19(1):89–93.

Foster SF, Slade P, Wilson K. Body image, maternal fetal attachment, and breast feeding. J Psychosom Res. 1996;41(2):181–4.

Krause KM, Lovelady CA, Østbye T. Predictors of breastfeeding in overweight and obese women: data from Active Mothers Postpartum (AMP). Matern Child Health J. 2011;15(3):367–75.

Bartok CJ, Schaefer EW, Beiler JS, Paul IM. Role of body mass index and gestational weight gain in breastfeeding outcomes. Breastfeed Med. 2012;7(6):448–56.

Reeves EA, Woods-Giscombé CL. Infant-feeding practices among African American women: Social-ecological analysis and implications for practice. J Transcult Nurs. 2014;26(3):219–26.

Sejrsen K, Purup S, Vestergaard M, Foldager J. High body weight gain and reduced bovine mammary growth: physiological basis and implications for milk yield potential. Domest Anim Endocrinol. 2000;19(2):93–104.

Flint DJ, Travers MT, Barber MC, Binart N, Kelly PA. Diet-induced obesity impairs mammary development and lactogenesis in murine mammary gland. Am J Physiol Endocrinol Metab. 2005;288(6):E1179–87.

Huggins K, Petok E, Mireles O. Markers of lactation insufficiency: a study of 34 mothers. Curr Issues Clin Lact. 2000;1:25–35.

Neifert MR, Seacat JM, Jobe WE. Lactation failure due to insufficient glandular development of the breast. Pediatrics. 1985;76(5):823–8.

Mok E, Multon C, Piguel L, Barroso E, Goua V, Christin P, et al. Decreased full breastfeeding, altered practices, perceptions, and infant weight change of prepregnant obese women: a need for extra support. Pediatrics. 2008;121(5):e1319–24.

Guelinckx I, Devlieger R, Bogaerts A, Pauwels S, Vansant G. The effect of pre- pregnancy BMI on intention, initiation and duration of breast-feeding. Public Health Nutr. 2012;15(5):840–8.

Segura-Millan S, Dewey KG, Perez-Escamilla R. Factors associated with perceived insufficient milk in a low-income urban population in Mexico. J Nutr. 1994;124(2):202–12.

Leonard SA, Labiner-Wolfe J, Geraghty SR, Rasmussen KM. Associations between high prepregnancy body mass index, breast-milk expression, and breast-milk production and feeding. Am J Clin Nutr. 2011;93(3):556–63.

Fernandes TA, Werneck GL, Hasselmann MH. Prepregnancy weight, weight gain during pregnancy, and exclusive breastfeeding in the first month of life in Rio de Janeiro, Brazil. J Hum Lact. 2012;28(1):55–61.

Leonard SA, Rasmussen KM. Larger infant size at birth reduces the negative association between maternal prepregnancy body mass index and breastfeeding duration. J Nutr. 2011;141(4):645–53.

Gaudet L, Tu X, Fell D, El-Chaar D, Wen SW, Walker M. The effect of maternal class III obesity on neonatal outcomes: a retrospective matched cohort study. J Maternal Fetal Neonatal Med. 2012;25(11):2281–6.

Rasmussen KM, Dieterich CM, Zelek ST, Altabet JD, Kjolhede CL. Interventions to increase the duration of breastfeeding in obese mothers: the Bassett Improving Breastfeeding Study. Breastfeed Med. 2011;6(2):69–75.

Chapman DJ, Morel K, Bermúdez-Millán A, Young S, Damio G, Pérez-Escamilla R. Breastfeeding education and support trial for overweight and obese women: a randomized trial. Pediatrics. 2013;131(1):e162–70.

Carlsen EM, Kyhnaeb A, Renault KM, Cortes D, Michaelsen KF, Pryds O. Telephone- based support prolongs breastfeeding duration in obese women: a randomized trial. Am J Clin Nutr. 2013;98(5):1226–32.

Franke RH, Kaul JD. The Hawthorne experiments: first statistical interpretation. Am Sociol Rev. 1978;43:623–43.

Dennis CL. Breastfeeding initiation and duration: a 1990–2000 literature review. J Obstet Gynecol Neonatal Nurs. 2002;31(1):12–32.

McLeod D, Pullon S, Cookson T. Factors influencing continuation of breastfeeding in a cohort of women. J Hum Lact. 2002;18(4):335–43.

Renfrew MJ, McCormick FM, Wade A, Quinn B, Dowswell T. Support for healthy breastfeeding mothers with healthy term babies. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2012;5:CD001141.

Kronborg H, Væth M. The influence of psychosocial factors on the duration of breastfeeding. Scand J Public Health. 2004;32(3):210–6.

McGrath SK, Kennell JH. A randomized controlled trial of continuous labor support for middle-class couples: effect on cesarean delivery rates. Birth. 2008;35(2):92–7.

Hodnett ED, Gates S, Hofmeyr GJ, Sakala C. Continuous support for women during childbirth. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2007;3:CD003766.

Chen DC, Nommsen-Rivers L, Dewey KG, Lonnerdal B. Stress during labor and delivery and early lactation performance. Am J Clin Nutr. 1998;68(2):335–44.

Dewey KG, Nommsen-Rivers LA, Heinig MJ, Cohen RJ. Risk factors for suboptimal infant breastfeeding behavior, delayed onset of lactation, and excess neonatal weight loss. Pediatrics. 2003;112(3 Pt 1):607–19.

Dewey KG. Maternal and fetal stress are associated with impaired lactogenesis in humans. J Nutr. 2001;131(11):3012S–5.

Cotterman KJ. Reverse pressure softening: a simple tool to prepare areola for easier latching during engorgement. J Hum Lact. 2004;20(2):227–37.

Colson SD, Meek JH, Hawdon JM. Optimal positions for the release of primitive neonatal reflexes stimulating breastfeeding. Early Hum Dev. 2008;84(7):441–9.

Brown D, Baker G, Hoover K. Breastfeeding tips for women with large breasts. J Hum Lact. 2013;29(2):261–2.

ABM Clinical Protocol #3. Hospital guidelines for the use of supplementary feedings in the healthy term breastfed neonate, Revised 2009. Breastfeed Med. 2009;4:3175–82.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported in part by an NIH grant (NIDDK-1R01DK096488-01A1) to ER and an International Lactation Consultant Association Research Grant to JB and ER.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Authors’ contributions

JB devised the original concept for the review, and carried out the bulk of the literature search and writing for the manuscript. ER devised the original concept for the review, and aided in the revision of multiple drafts. EM devised the original concept for the review, and aided in the revision of multiple drafts. MWM aided with the literature search, making edits to multiple drafts of the paper, and formatting for final submission. YRD aided in the conception of the paper and in the revision of multiple drafts. All authors approved the final draft of this manuscript.

Rights and permissions

This article is published under an open access license. Please check the 'Copyright Information' section either on this page or in the PDF for details of this license and what re-use is permitted. If your intended use exceeds what is permitted by the license or if you are unable to locate the licence and re-use information, please contact the Rights and Permissions team.

About this article

Cite this article

Bever Babendure, J., Reifsnider, E., Mendias, E. et al. Reduced breastfeeding rates among obese mothers: a review of contributing factors, clinical considerations and future directions. Int Breastfeed J 10, 21 (2015). https://doi.org/10.1186/s13006-015-0046-5

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s13006-015-0046-5