Abstract

Background

Despite the importance of local markets as a source of medicinal plants in Colombia, comparatively little comparative research reports on the pharmacopoeiae sold. This stands in contrast to wealth of available information for other components of plant use in Colombia and other countries. The present provides a detailed inventory of the medicinal plant markets in the Bogotá metropolitan area, hypothesizing that the species composition, and medicinal applications, would differ across markets of the city.

Methods

From December 2014 to February 2016, semi-structured interviews were conducted with 38 plant vendors in 24 markets in Bogotá in order to elucidate more details on plant usage and provenance.

Results

In this study, we encountered 409 plant species belonging to 319 genera and 122 families. These were used for a total of 19 disease categories with 318 different applications. Both species composition and uses of species did show considerable differences across the metropolitan area—much higher in fact than we expected.

Conclusions

The present study indicated a very large species and use diversity of medicinal plants in the markets of Bogotá, with profound differences even between markets in close proximity. This might be explained by the great differences in the origin of populations in Bogotá, the floristic diversity in their regions of origin, and their very distinct plant use knowledge and preferences that are transferred to the markets through customer demand. Our study clearly indicated that studies in single markets cannot give an in-depth overview on the plant supply and use in large metropolitan areas.

Similar content being viewed by others

Background

Like in many tropical countries, traditional knowledge in Colombia is still under-documented [1,2,3], despite the fact that the country could be called the “cradle of modern ethnobotany”, due to the decade long research of Richard Evans Schultes [4]. General ethnobotanical studies in Colombia have frequently focused on individual interesting species [5,6,7,8,9,10,11,12,13], specific medicinal applications (e.g., antiviral and antitumor activity) [14, 15], leishmaniasis [16], snake bites [17,18,19,20,21], crops and economically important plants [10, 22,23,24,25], or specific plant families [26,27,28,29,30,31,32,33]. Individual ethnic groups were recently treated by a variety of authors [34,35,36,37,38]. Columbian medicinal plant use has even been studied overseas [39].

However, in contrast to neighboring countries like Peru and Bolivia [31, 40,41,42,43,44,45,46,47,48,49,50], although Lima et al. [51] provided a comparison of markets in the wider Amazon.

Thus, for Colombia there is very little comparative information available about which plants are sold in Colombian markets, under which vernacular name at any given time, for which indication, which dosage information, and what kind of information about side effects vendors provide to their clients. The present study attempts to remedy this situation by providing a detailed inventory of medicinal plant markets in the Bogotá metropolitan area. We hypothesized that, on the one hand, like in Peru and Bolivia [31, 40,41,42,43,44,45,46,47,48,49,50] the plant and use composition of different markets would vary depending on their location and customer population, but that, on the other hand, there would overall be a large overlap in plants between markets, and larger markets would comprise an almost complete inventory of all species available.

Methods

Ethnobotanical inventory

From December 2014 to February 2016, semi-structured interviews were conducted with 38 plant vendors in 24 markets in Bogotá in order to elucidate more details on plant usage and provenance. The markets were chosen to cover as many neighborhoods of Bogotá as possible, thus trying to represent the complete geography of the city and its ethnically diverse population. Plants were always sold in the regular mercados de abasto—the regular food supply markets. Within a neighborhood, we always chose the main market, in order to make data comparable. Semi-structured interviews following [49] are under consideration of the collection standards established by [52]. During the interviews, a complete sample of all plants sold in a respective market stall was bought and all available information for each species elucidated from the vendor. Vendor participants were self-selected: every vendor in the studied markets was asked if they wanted to participate in the study, and the vendors who agreed were then interviewed. Overall about one third of the vendors in the markets participated in the interviews. Interviews were conducted only after explaining the study to all participants and obtaining their oral prior informed consent. No further ethics approval was required. All work was carried out following the International Society for Ethnobiology Code of Ethics [53] and under the framework provided by the Nagoya Protocol on Access to Genetic Resources and Fair and equitable sharing of benefits arising from their use of the Convention on Biological Diversity; the interviewed vendors retain the copyright of their traditional knowledge. Any commercial use of any of the information requires prior consensus with the informants involved, and an agreement on the distribution of benefits.

Twenty-six of the participants were women, and 12 men, with ages ranging from 25 to 70 years. The ethnicity of the vendors was not disclosed. All interviews were conducted in Spanish.

Vouchers of all species were collected, and all plant material was identified at the National Herbarium of Colombia. No material whatsoever was exported from Colombia. The nomenclature of all species follows www.tropicos.org, under APG III [54].

Statistical analysis

Among markets we compared plant species reported as being used (unique Latin binomials, e.g., Aloe vera), plant uses (unique combinations of a species used for an ailment or illness, e.g., Aloe vera for eye irritation), and plant categories (unique combinations of a species used for a category of ailments, e.g., Aloe vera sensory system).

To compare the geographic/market structure of plants and plant uses, we extracted lists of unique and shared plants, plant uses, and plant categories in each market [55]. In addition to these raw counts, we also used Euclidian distance as a metric of the difference among markets.

To evaluate plant importance, we used the logarithmic informant consensus (LIC) index of [56]. Here, we considered markets as “occurrences,” so for a species:

where for each use of a species ICu = (FCu − NSu)/(FCu − 1), FCu is the total reports of that use and NSu is the number of species reported for the use.

To evaluate the diversity of uses across markets, we calculated, for each plant that occurs in at least two markets, the percent of its uses that are unique to each market.

All analyses were performed using the R program package [57].

Results

In this study, we encountered 409 plant species belonging to 319 genera and 122 families in all markets studied (Table 1). In all markets, the most common plant families used were Fabaceae (43 species, 10.5%), Asteraceae (34 species, 8.3%), Lamiaceae (24 species, 5.8%), Malvaceae (16 species, 3.9%), Solanaceae (15 species, 3.7%), and Euphorbiaceae (13 species, 3.1%). Almost all of all species were known only by their Spanish names.

Most remedies were taken orally as decoctions/infusions, and a much smaller number was applied as cataplasm. Applications involved preferentially leaves and aerial parts of the plant.

Four hundred two species were used for medicinal purposes. The most treated illness categories were Non-specific symptoms and general illnesses (223 species, 55.4%), Digestive system (208, 52%), Skin and subcutaneous tissue (142, 35.3%), Respiratory system (131, 32.6%), Urinary system (119, 29.6%), Blood and circulatory system (107, 26.6%), and Infections and infestations (100, 24.8%). Among the individual illnesses, indigestion (167 species, 41.5%) stood out as the most common illness, followed by diuretic uses (155, 38.5%), emmenagogues (125, 32%), and flatulence (123, 30.5%) and rheumatism, diarrhea, and use as laxative (120, 119, and 166 species, 30, 29.5, and 29%, respectively).

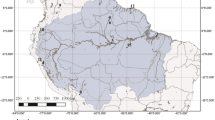

In the present study, almost without exception, the small markets contained much less species than the main markets. Markets in Bogotá had very large numbers of unique plants, and the difference between the plants they report is not explained by geographical factors (the main origin of a human population within different districts in Bogotá) (by 9 geographical zones: p = 0.37; by 15 localities: p = 0.41) or size (by number of species reported: p = 0.22) (Fig. 1). The proportion of unique plants in the markets of Bogotá was generally high and did not show relations to geography or market size (Fig. 2). Even the 11 plant species that were most widespread among all markets did in fact occurred only in relatively few markets (Fig. 3). Not surprisingly, while generally low informant consensus (IC) was highest for introduced species (Table 2).

Discussion

Overall, species richness encountered in Bogotá was considerably higher than reported in studies in Bolivia [50] but similar to what we encountered in Peru [40,41,42,43,44,45,46,47,48,49]. The numbers of species used for each illness was astonishingly high in comparison to the studies in Bolivia and Peru cited above. In contrast to studies in Peru [42, 43, 49], or even Bolivia [50], the species composition and plant use divergence in the markets of Bogotá were also very high. This was in contrast to both our initial hypotheses: While we had expected some discrepancy in plant composition and use in different markets, very much like in Peru [42, 43, 49] and Bolivia [50], the differences between the markets in Bogotá were much larger. Similarly, in contrast to the expectation that larger markets would contain all plant species found in smaller markets, essentially every market in Bogotá was unique. Rather than reflecting shared colonial heritage in plant use, the markets in Bogotá reflected much more the origin of the surrounding population, and each market focused more on the plant resources from the populations’ origin area. This might reflect that the human population of Bogotá, with migrants from all over Colombia, is much more diverse than the populations in the comparison areas (Trujillo-Chiclayo in Peru with mostly coastal population and Andean migrants; La Paz with a mixed population of Quechua and Mestizo origin).

Conclusions

The present study indicated a very large species and use diversity of medicinal plants in the markets of Bogotá, with profound differences existing even between markets in close proximity. This might be explained by the great differences in the origin of populations in Bogotá, the floristic diversity in their regions of origin, and their very distinct plant use knowledge and preferences that are transferred to the markets through customer demand. Our study clearly indicates that studies in single markets cannot give an in-depth overview on the plant supply and use in large metropolitan areas.

Abbreviations

- FCu:

-

Use reports for a specific use

- IC:

-

Informant consensus

- ICu:

-

Informant consensus for a specific use

- LIC:

-

Logarithmic informant consensus

- NSu:

-

Species for a specific use

References

Albuquerque UP, Silva JS, Campos JLA, Sousa RS, Silva TC, Alves RRN. The current status of ethnobiological research in Latin America: gaps and perspectves. J Ethnobiol Ethnobiomed. 2013;9(1) https://doi.org/10.1186/1746-4269-9-72.

Cámara-Leret R, Paniagua-Zambrana N, Balslev H, Macía MJ. Ethnobotanical knowledge is vastly under-documented in northwestern South America. PLoS One. 2014;9(1) https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0085794.

Cámara-Leret R, Paniagua-Zambrana N, Svenning J-C, Balslev H, Macía MJ. Geospatial patterns in traditional knowledge serve in assessing intellectual property rights and benefit-sharing in Northwest South America. J Ethnopharmacol. 2014;158(A):58–65. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jep.2014.10.009.

Bussmann RW. I know every tree in the forest: reflections on the life and legacy of Richard Evans Schultes. In: Ponman B, Bussmann RW, editors. Proceedings of the Botany 2011 Richard E Schultes Symposium. St. Louis: William L. Brown Center; 2012. p. 13–22.

Schultes ER, Plowman T. The ethnobotany of Brugmansia. J Ethnopharmacol. 1979;1(2):147–64.

Álvarez Salas LM, Turbay Ceballos S. El fríjol petaco (Phaseolus coccineus) y la maravilla (Phaedranassa sp.): Aspectos etnobotánicos de dos plantas alimenticias de origen Americano en el Oriente Antioqueño, Colombia. Agroaliment. 2009;15(29):101–13.

Alarcón JCP, Martinez DMR, Salazar-Ospina A. Propagación in vitro de Heliconia curtispatha p, planta utilizada contra la mordedura de serpientes por algunas comunidades campesinas de la región colombiana del Urabá. Vitae. 2011;18(3):271–8.

Dey A, Mukherjee A. Plumeria rubra L. (Apocynaceae): ethnobotany, phytochemistry and pharmacology: a mini review. J Pl Sci. 2015;10(2):54–62. https://doi.org/10.3923/jps.2015.54.62.

Sequeda-Castañeda LG, Célis C, Gutiérrez S, Gamboa F. Piper marginatum Jacq. (Piperaceae): phytochemical, therapeutic, botanical insecticidal and phytosanitary uses. Pharmacolog Onl. 2015;3:136–45.

Sequeda-Castañeda LG, Célis C, Gutiérrez S, Luengas-Caicedo PE. Berberis rigidifolia Kunth. (Berberidaceae) Colombian endemic plant. Pharmacolog Onl. 2016;4(1):134–8.

Sequeda-Castañeda LG, Célis C, Ortíz-Ardila AE. Phytochemical and therapeutic use of Cecropia mutisiana Mildbr. (Urticaceae) an endemic plant from Colombia. Pharmacolog Onl. 2015;3:146–8.

Sequeda-Castañeda LG, Célis C, Ortíz-Ardila AE. Phytochemical and therapeutic use of Cecropia mutisiana Mildbr. (Urticaceae) an endemic plant from Colombia. (2015). Pharmacolog Onl. 2015;3:62–4.

Sequeda-Castañeda LG, Modesti Costa G, Celis C, Gamboa F, Gutiérrez S, Luengas P. Ilex guayusa loes (Aquifoliaceae): Amazon and Andean native plant. Pharmacolog Onl. 2016;3:193–202.

Betancur-Galvis LA, Morales GE, Forero JE, Roldan J. Cytotocxic and antiviralactivties of Colombian medicinal plant extracts of the Euphorbia genus. Mem Inst Osw Cruz. 2002;97(4):541–6.

Betancur-Galvis LA, Saez J, Granados H, Salazar A, Ossa JE. Antitumor and antiviral activity of Colombian medicinal plant extracts. Mem Inst Osw Cruz. 1999;94(4):531–5. https://doi.org/10.1590/S0074-02761999000400019.

Bernal Gutiérrez JM, López Ortiz AF, Perea EM, Jairo Méndez J. Wild medicinal plants used by Colombian Kofan Indians to treat cutaneous leishmaniasis. Rev Cub Plant Med. 2014;19(4):407–20.

Otero R, Fonnegra R, Jiménez SL, Núñez V, Evans N, Alzate SP, García ME, Saldarriaga M, Del Valle G, Osorio RG, Díaz A, Valderrama R, Duque A, Vélez HN. Snakebites and ethnobotany in the northwest region of Colombia. Part I: traditional use of plants. J Ethnopharmacol. 2000;71(3):493–504. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0378-8741(00)00243-9.

Otero R, Núñez V, Barona J, Fonnegra R, Jiménez SL, Osorio RG, Saldarriaga M, Díaz A. Snakebites and ethnobotany in the northwest region of Colombia. Part III: neutralization of the haemorrhagic effect of Bothrops Atrox venom. J Ethnopharmacol. 2000;73(1–2):233–41. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0378-8741(00)00321-4.

Otero R, Núñez V, Jiménez SL, Fonnegra R, Osorio RG, García ME, Díaz A. Snakebites and ethnobotany in the northwest region of Colombia. Part II: neutralization of lethal enzymatic effects Bothrops Atrox venom. J Ethnopharmacol. 2000;71(3):505–11. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0378-8741(99)00197-X.

Vásquez J, Alarcón JC, Jiménez SL, Jaramillo GI, Gómez-Betancur IC, Rey-Suárez JP, Jaramillo KM, Muñoz DC, Marín DM, Romero JO. Main plants used in traditional medicine for the treatment of snake bites n the regions of the Department of Antioquia, Colombia. J Ethnopharmacol. 2015;170:58–166. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jep.2015.04.059.

Vásquez J, Jiménez SL, Gómez IC, Rey JP, Henao AM, Marín DM, Romero JO, Alarcón JC. Snakebites and ethnobotany in the eastern region of Antioquia, Colombia—the traditional use of plants. J Ethnopharmacol. 2013;146(2):449–55. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jep.2012.12.043.

B. 1999. Dispersion and ethnobotany of the cacao tree and other Amerindian crop plants. J Appl Bot 1999;73(3–4):128–137.

Frausin G, Trujillo E, Correa MA, Gonzalez VH. Seeds used in handicrafts manufactured by an Emberá-Katío indigenous population displaced by violence in Colombia. Caldasia. 2008;30(2):315–23.

Clement CR, Zizumbo-Villarreal D, Brown CH, Ward RG, Alves-Pereira A, Harries HC. Coconuts in the Americas. Bot Rev. 2013;79(3):342–70. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12229-013-9121-z.

Pinzón-Rico YA, Raz L. Commercialization of Andean wild yam species (Dioscorea L.) for medicinal use in Bogotá, D.C., Colombia. Econ Bot. 2017;71(1):45–57. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12231-017-9371-5.

Macía MJ, Armesilla PJ, Cámara-Leret R, Paniagua-Zambrana N, Villalba S, Balslev H, Pardo-de-Santayana M. Palm uses in northwestern South America: a quantitative review. Bot Rev. 2011;77(4):462–570. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12229-011-9086-8.

Mesa-C LI, Galeano G. Uso y manejo de las palmas (Arecaceae) por los piapoco del norte de la amazonia Colombiana. Act Bot Venezuel. 2013;36(1):15–38.

Ledezma-Rentería ED, Galeano G. Usos de las palmas en las tierras bajas del Pacífico Colombiano. Caldasia. 2014;36(1):71–84.

Paniagua-Zambrana, N, Cámara-Leret, R, Bussmann, RW, Macía, MJ. Understanding transmission of traditional knowledge across North-Western South America: a cross-cultural study in palms (Arecaceae). Bot J Linn Soc 2′16;182(2):480–504. DOI: https://doi.org/10.1111/boj.12418.

Paniagua-Zambrana N, Cámara-Leret R, Macía MJ. Patterns of medicinal use of palms across northwestern South America. Bot Rev. 2015;81(4):317–415. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12229-015-9155-5.

Paniagua-Zambrana NY, Bussmann, RW, Macia, MJ. Changing markets, changing uses—the example of Euterpe precatoria Mart. and E. oleracea Mart. in Bolivia and Peru. J Ethnobiol Ethnobiomed. 2017;13(32). https://doi.org/10.1186/s13002-017-0160-0.

Paniagua-Zambrana, NY, Camara-Lerét, R, Bussmann, RW, Macía, MJ. The influence of socioeconomic factors on traditional knowledge: A cross scale comparison of palm use in northwestern South America. Ecol Soc. 12014;9(4). DOI: https://doi.org/10.5751/ES-06934-190409

Laureto LMO, Cianciaruso MV. Palm economic and traditional uses, evolutionary history and the IUCN red list. Biodivers Conserv. 2017;26(7):1587–600. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10531-017-1319-7.

Galeano G. Forest use at the Pacific coast of Choco, Colombia: a quantitative approach. Econ Bot. 2000;54(3):358–76. https://doi.org/10.1007/BF02864787.

Estupiñán-González AC, Jiménez-Escobar ND. Uso de las plantas por grupos campesinos en la franja tropical del parque nacional natural paramillo (Córdoba, Colombia). Caldasia. 2010;32(1):21–38.

Jiménez-Escobar ND, Rangel-Ch JO. La abundancia, la dominancia y sus relaciones con el uso de la vegetación arbórea en la bahía de cispatá, caribe Colombiano. Caldasia. 2012;34(2):347–66.

Carbonó-Delahoz E, Dib-Diazgranados JC. Plantas medicinales usadas por los Cogui en el río Palomino, Sierra Nevada de Santa Marta (Colombia). Caldasia. 2013;35(2):333–50.

Rengifo-Salgado E, Rios-Torres S, Malaverri LF, Vargas-Arana G. Saberes ancestrales sobre el uso de flora y fauna en la comunidad indígena Tikuna de Cushillo Cocha, zona fronteriza Perú-Colombia-Brasil. Rev Per Biol. 2017;24(1):67–78. https://doi.org/10.15381/rpb.v24i1.13108.

Ceuterick M, Vandebroek I, Torry B, Pieroni A. Cross-cultural adaptation in urban ethnobotany: the Colombian folk pharmacopoeia in London. J Ethnopharmacol. 2008;120(3):342–59. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jep.2008.09.004.

Bussmann RW. The globalization of traditional medicine in northern Peru—from shamanism to molecules. Ev Bas Compl Alt Med. 2013;291903 https://doi.org/10.1155/2013/291903.

Bussmann RW, Sharon D, Vandebroek I, Jones A, Revene Z. Health for sale: the medicinal plant markets in Trujillo and Chiclayo, northern Peru. J Ethnobiol Ethnobiomed. 2007;3:37.

Bussmann RW, Sharon D, Garcia M. From chamomile to aspirin? Medicinal plant use among clients at Laboratorios Beal in Trujillo, Peru. Ethnobot Res Appl. 2009;7:399–407.

Bussmann RW, Sharon D. Markets, healers, vendors, collectors—the sustainability of medicinal plant use in northern Peru. Mt Res Dev. 2009;29(2):128–34.

Bussmann RW, Sharon D, Ly J. From garden to market? The cultivation of native and introduced medicinal plant species in Cajamarca, Peru and implications habitat conservation. Ethnobot Res Appl. 2008;6:351–61.

Bussmann RW, Glenn A, Meyer K, Rothrock A, Townesmith A. Herbal mixtures in traditional medicine in northern Peru. J Ethnobiol Ethnobiomed. 2010;6:10. https://doi.org/10.1186/1746-4269-6-10.

Revene Z, Bussmann RW, Sharon D. From sierra to coast: tracing the supply of medicinal plants in northern Peru—a plant collector’s tale. Ethnobot Res Appl. 2008;6:15–22.

Bussmann RW, Sharon D. Medicinal plants of the Andes and the Amazon—the magic and medicinal flora of northern Peru. St. Louis: William L. Brown Center; 2015.

Bussmann RW, Sharon D. Plantas medicinales de los Andes y la Amazonía—La flora mágica y medicinal del Norte de Peru. St. Louis: William L. Brown Center; 2015.

Bussmann RW, Sharon D. Traditional plant use in northern Peru: tracking two thousand years of healing culture. J Ethnobiol Ethnobiomed. 2006;2:47.

Bussmann RW, Paniagua Zambrana NY, Moya Huanca LA, Hart RE. Changing markets—medicinal plants in the markets of La Paz and El Alto, Bolivia. J Ethnopharmacol. 2016;193:76–95.

Lima PGC, Coelho–Ferreira M, da Silva Santos R. Perspectives on medicinal plants in public markets across the Amazon: a review. Econ Bot. 2016;70(1):64–78. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12231-016-9338-y.

Cook, FGM. 1995. Economic botany data collection standard. Royal Botanical Gradens Kew. Kent; 1995.

International Society of Ethnobiology. International Society of Ethnobiology Code of Ethics (with 2008 additions). 2006; http://www.ethnobiology.net/what-we-do/core-programs/ise-ethics-program/code-of-ethics/code-in-english/. Accessed 07/01/2018.

Angiosperm Phylogeny Group. An update of the angiosperm phylogeny group classification for the orders and families of flowering plants: APG III. Bot J Linn Soc. 2009;161(1):105–21.

Wilkinson, L. 2011. Venneuler: Venn and Euler diagrams. R package version 1.1–0. http://CRAN.R-project.org/package=venneuler

Dudney K, Warren S, Sills E, Jacka J. How study design influences the ranking of medicinal plant importance: a case study from Ghana, West Africa. Econ Bot. 2015;30:1–12.

Oksanen J, Blanchet FG, Kindt R, Legendre P, Minchin PR, O’Hara RB, Simpson GL, Solymos P, Henry M, Stevens H, Wagner H. Vegan: community ecology package. <https://CRAN.R-project.org/package=vegan>; 2016.

Acknowledgements

We gratefully acknowledge the participation of the market vendors in Bogotá, and the Herbario Nacional de Colombia for access to comparative plant material.

Funding

This study was funded endowment funds of the William L. Brown Center at Missouri Botanical Garden, for which we are grateful.

Availability of data and materials

The raw data without names of participants are available from the authors.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

RWB and NYPZ designed the study; CR conducted the fieldwork; RHE conducted the main statistical analysis; RBU, NYPZ, CM, and RHE analyzed the data and wrote the manuscript. All authors read, corrected, and approved the manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

Before conducting interviews, the individual prior informed consent was obtained from all participants. No further ethics approval was required. All work conducted was carried out under the stipulations of the Nagoya Protocol on Access to Genetic Resources and the Fair and Equitable Sharing of Benefits Arising from their Utilization to the Convention on Biological Diversity. The right to use and authorship of any traditional knowledge of all participants is maintained, and any use of this information, other than for scientific publication, does require additional prior consent of the traditional owners, as well as a consensus on access to benefits resulting from subsequent use.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made. The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver (http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/) applies to the data made available in this article, unless otherwise stated.

About this article

Cite this article

Bussmann, R.W., Paniagua Zambrana, N.Y., Romero, C. et al. Astonishing diversity—the medicinal plant markets of Bogotá, Colombia. J Ethnobiology Ethnomedicine 14, 43 (2018). https://doi.org/10.1186/s13002-018-0241-8

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s13002-018-0241-8