Abstract

Background

Traditional ecological knowledge among indigenous communities plays an important role in retaining cultural identity and achieving sustainable natural resource management. Hundreds of millions of people mostly in developing countries derive a substantial part of their subsistence and income from plant resources. The aim of this study was to assess useful plant species diversity, plant use categories and local knowledge of both wild and cultivated useful species in the Eastern Cape province, South Africa.

Methods

The study was conducted in six villages in the Eastern Cape province, South Africa between June 2014 and March 2017. Data on socio-economic characteristics of the participants, useful plants harvested from the wild, managed in home gardens were documented by means of questionnaires, observation and guided field walks with 138 participants.

Results

A total of 125 plant species belonging to 54 genera were recorded from the study area. More than half of the species (59.2%) are from 13 families, Apiaceae, Apocynaceae, Araliaceae, Asparagaceae, Asphodelaceae, Asteraceae, Fabaceae, Lamiaceae, Malvaceae, Myrtaceae, Poaceae, Rosaceae and Solanaceae. More than a third of the useful plants (37.6%) documented in this study are exotic to South Africa. About three quarters of the documented species (74.4%) were collected from the wild, while 20.8% were cultivated and 4.8% were spontaneous. Majority of the species (62.4%) were used as herbal medicines, followed by food plants (30.4%), ethnoveterinary medicine (18.4%), construction timber and thatching (11.2%). Other minor plant use categories (1–5%) included firewood, browse, live fence, ornamentals, brooms and crafts.

Conclusion

This study demonstrated that local people in the Eastern Cape province harbour important information on local vegetation that provides people with food, fuel and medicines, as well as materials for construction and the manufacturing of crafts and many other products. This study also demonstrated the dynamism of traditional ecological knowledge, practices and beliefs of local people demonstrated by the incorporation of exotic plants in their diets and indigenous pharmacopoeia.

Similar content being viewed by others

Background

Plant biodiversity provide humans with four categories of ecosystem goods and services which are provisioning, regulating, supporting and cultural services [1]. Their direct provisioning services to humans are food, fodder, medicines, timber, fuelwood and grazing, while regulating services include moderating air and water quality and erosion control [2]. Plant species also play a vital role in supporting services such as soil formation, and nutrient and water cycling and in cultural services, including traditional human knowledge systems [2]. Therefore, plant biodiversity is required to fulfill various human daily livelihood needs. According to Uprety et al. [3] hundreds of millions of people, mostly in developing countries, derive a substantial part of their subsistence and income from wild plant products. Research by Sunderland [4] revealed that plant biodiversity provides an important safety net during times of food insecurity, particularly during times of low agricultural production, during other seasonal or cyclical food gaps or during periods of climate induced vulnerability. Plant resources collected from the wild are an important safety net and source of livelihood needs especially for the poor and those people who live in marginalized areas who rely on them for food, fuelwood, medicines and building materials. In sub-Saharan Africa, the loss of traditional ecological knowledge (TEK) among indigenous communities has been described as one of the greatest challenges to the continent for retaining cultural continuity and achieving sustainable natural resource management [5,6,7,8,9,10,11]. Berkes et al. [12] defined TEK as a cumulative body of knowledge, practice and belief, evolving by adaptive processes and handed down over generations by cultural transmission, about the relationships between living beings and their environment. Similarly, research by Harisha et al. [13] revealed that TEK is a key element of the social capital to produce food, primary healthcare and in shaping local visions and perceptions of the surrounding environment and society. Traditional ecological knowledge has contributed to conservation of biodiversity, rare species and protected areas as well as to sustainable natural resource use in several countries throughout the world [14].

Given the widespread decline of TEK about plant diversity in sub-Saharan Africa [6, 7, 9, 14], there is therefore, need to document this traditional knowledge which has accumulated over centuries and transferred orally from generation to generation. Van Wyk and Gericke [15] argued that changes in the socio-cultural and environmental landscapes over the past decades resulted in the erosion of TEK of local communities. Such changes include improved access to modern health care services, improved education system, shifts of populations from rural to urban centres, changes from subsistence farming to cash-crop production, reliance on migrant labour and unprecedented environmental degradation. Research by Van Wyk and Gericke [15] revealed that the use of plants by local people is still a relatively underdeveloped discipline in southern Africa and knowledge of indigenous plant use in the region needs urgent scientific documentation before it is irretrievably lost to future generations. It is within this context that assessment of plant diversity, use and local knowledge of both wild and cultivated species was carried out in the Eastern Cape province, South Africa.

The Eastern Cape province is approximately 170,000 km2 in area and is inhabited by about 6.7 million people, which equals about 13.8% of both the total population and the total land area of South Africa [16]. This province is predominantly inhabited by isiXhosa speaking people of Cape Nguni descent. The Eastern Cape province includes two of the former homeland areas, namely Ciskei and Transkei out of the 13 former racially-defined homelands or Bantustan areas of South Africa. One of the Apartheid government’s acts of segregation was the Bantu Authorities Act of 1951, which legalized the deportation of Black people into designated homelands. Black people were forcibly removed from urban areas and white farms to those areas demarcated as homelands. The Ciskei and Transkei are today characterized by landlessness, pervasive chronic poverty, low levels of education, economic activity, vulnerability, lack of basic services, a dearth of employment opportunities and high levels of dependency on welfare [17]. An estimated 72% of the population in the Eastern Cape province live below the poverty line, which is more than the national average of 60% and this is attributed to the legacies of Apartheid; where the Eastern Cape provincial administration inherited the largely impoverished and corrupt former Ciskei and Transkei homelands [18]. Research by Westaway [17] revealed that the majority of households in the Eastern Cape province spend most of their income on food and there is clear evidence of growing food insecurity as measured by the number of meals consumed and the quantity and variety of foods eaten. Most people in the province live in rural areas, the contribution of agriculture to local livelihoods is low in the entire province and has been in decline for several decades [19]. However, research by Shackleton et al. [20] revealed that local people’s livelihoods in the province are centred on grasslands and forests for fodder, wild foods, firewood, medicinal plants and fibre species for weaving. Therefore, the current study was undertaken to assess diversity of use and local knowledge of wild and cultivated plants in the Eastern Cape province. This study was carried out to gather support for the hypothesis that the Eastern Cape province is historically linked to peasant and indigenous people who derive their livelihoods from the surrounding plant resources contributing to TEK about plant biodiversity in the province. Other researchers, for example, Harisha et al. [13] and Irakiza et al. [14] argued that TEK is an expression of cultural diversity which has been instrumental in the characterization of plant biodiversity, promotion of resilience of ecosystems, conservation and management of natural resources and meeting basic livelihood needs of local communities. Therefore, insight on useful plant species diversity, plant use categories and TEK associated with such plant species in the Eastern Cape province was documented in this study.

Methods

Study area

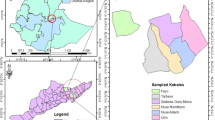

The study was conducted in six villages: Mpetsheni and Ngxoto villages (study site 1, see Fig. 1) in the Elundi Local Municipality; Colosa and Mangathi villages, study site 2 in the Mbhashe Local Municipality and Ngqele and KwaKhayalethu villages (study site 3, Fig. 1) in the Raymond Mhlaba Local Municipality. Study sites 1 and 2 are situated in the former Transkei homeland while study site 3 is situated in the former Ciskei homeland. Study sites 1 and 2 are predominantly rural with the dominant land use practise being rearing of livestock and dryland crop production. Major crops cultivated in the study area include maize (Zea mays L.), potatoes (Solanum tuberosum L.), cabbage (Brassica oleracea L.), spinach (Spinacia oleracea L.), beetroot (Beta vulgaris L.) and carrots (Daucas carota L.). The majority of the inhabitants (at least 87%) in the study sites are traditional isiXhosa speaking people who are highly dependent on natural resources for their livelihoods [21]. According to Chalmers and Fabricus [22], the vegetation of Mbhashe Local Municipality can best be described as grassland-woodland-forest mosaic, with a clear distinction between the boundaries of forests, woodland and grassland because of the effects of fire and clearing for cultivation. Mucina and Rutherford [23] described the vegetation of Ugie and Maclear, the two towns nearest to study site 1 as Drakensberg foothill moist grassland. This vegetation type occurs at an altitude of 880–1860 m above sea level with the landscape characterized by moderately rolling hills [23]. The grassland of both study sites 1 and 2 generally occurs on the high ridges, whereas the forest patches occur on the moist deeper soils in the protected valleys with the woodland in transition zone between the forest and the grassland. Study sites 1 and 2 are located in a climatic transition zone between the temperate south coast and the subtropical north coast of South Africa with average annual rainfall of 1069 mm, average winter and summer temperatures of 21.5 °C and 24 °C respectively [24].

The climate of study site 3 in the Raymond Mhlaba Local Municipality can be described as mild with unevenly distributed annual rainfall within the area with most rain falling during summer months from October to March. Annual rainfall ranges from 500 mm to 1000 mm, with mountainous areas receiving the highest rainfall and low to medium areas characterized by low to average annual rainfall [25, 26]. The climate varies from hot in summer to extreme cold in winter with heavy frost and snowfall along the hilly areas. The temperature ranges from of 4 °C in July to 38 °C in February [25, 26]. Raymond Mhlaba Local Municipality is characterized by a variety of land uses ranging from commercially oriented rangeland stock farming to small-scale vegetable and crop production and stock farming [25]. Other economic activities in the Raymond Mhlaba Local Municipality include tourism, forestry and sheep and wool production [26]. According to the vegetation classification of Mucina and Rutherford [23], the Raymond Mhlaba Local Municipality has grassland, succulent thicket and Acacia thornveld dominated by Acacia karroo Hayne, Aloe ferox Mill., Aloe aborescens Mill., Diospyros dichrophylla (Grand.) De Winter, Eragrostis curvula (Schrad.) Nees, Euphorbia spp., Melinis nerviglumis (Franch.) Zizka and Olea europaea L. ssp. africana (Mill.) P. S. Green.

Data collection

Data on diversity of use and local knowledge of wild and cultivated plants in six villages namely Colosa, KwaKhayalethu, Mangathi, Mpetsheni, Ngqele and Ngxoto in the former Ciskei and Transkei homelands (Fig. 1) were collected by means of questionnaires between June 2014 and March 2017. Participatory rural appraisal (PRA) methods were used [27, 28] aimed at incorporating the TEK and opinions of community members about useful plant species diversity and plant use categories species in the Eastern Cape province. Interviews and dialogue with the participants were an integral part of this research, enabling the researcher to understand a lot on the people’s resource use culture [27, 28]. The PRA exercises, though they are difficult to quantify, provide a valuable insight into the multiple meanings, dimensions and experiences of local people with plant resources around them. This research technique captures information that standard plant use assessment methods are likely to miss. Open-ended methods, such as unstructured interviews and discussion groups allow the emergence of issues and dimensions that are important to the community but not necessarily known to the researcher, thus allowing unanticipated themes to be explored by the interviewer [29].

One hundred and thirty eight (Table 1) randomly selected participants who took part in this study were requested to sign University of Fort Hare (MAR011) informed consent form and researchers also adhered to the ethical guidelines of the International Society of Ethnobiology (www.ethnobiology.net). The majority of these participants (65.9%) were females and their age range was from 19 to 81 years (Table 1). More than 80% of the participants live below the national poverty line and 62.3% of the households had total income of less than R1000.00 (US$87.00) per month (Table 1). Close to three quarters of the participants (73.9%) were unemployed, with 63.0% surviving on social grants (Table 1).

The aim and objectives of the study were presented to the participants before being interviewed. Results obtained via use of the questionnaires were complemented with personal observation, informal discussions and guided field walks or surveys with the participants. Interview discussions took place in the local language, isiXhosa and were translated into English with the help of an interpreter. During the interviews we documented information on names of useful plants, including species grown and managed in home gardens, uses, plant parts used and preparation of useful plants. Plant species were identified in the field and the taxon names conform to those of Germishuizen et al. [30]. Unknown plant species were collected, pressed, oven-dried and identified by taxonomists at the Giffen Herbarium (UFH) at the University of Fort Hare and Schonland Herbarium (GRA) at Rhodes University, Grahamstown, South Africa.

Data management and analysis

The data collected were entered in Microsoft Excel 2007 file and this data were used to determine frequencies and other descriptive statistical patterns. Box plots featuring medians, first and third quartiles and a range of plant use categories were computed using Palaeontological Statistics [31], version 3.06. The majority of the data collected in this study were descriptive and qualitative in nature, and therefore, were explained directly. Interview responses from participants were coded and sorted into themes, paying particular attention to inconsistencies and unique statements.

Results and discussion

Plant diversity

A total of 125 plant species were recorded in the Eastern Cape province (Table 2), with herbs, trees and shrubs having the most species (Fig. 2). Pteridophytes and gymnosperms were represented by a single species each, that is, Cheilanthes hirta (family Pteridaceae) and Podocarpus latifolius (family Podocarpaceae) respectively. A large number (59.2%, n = 74) of the plant species recorded in this study are from 13 families (Table 3). The other 41 families had less representation, between one and two species each. Plant families with the highest number of species were: Asteraceae (10 species), Fabaceae and Solanaceae (nine species each), Poaceae (eight species), Asphodelaceae (seven species), Rosaceae (five species), Apiaceae, Apocynaceae, Asparagaceae, Lamiaceae and Myrtaceae (four species each), Araliaceae and Malvaceae (three species each) (Table 3). All these plant families with the exception of Araliaceae are among the largest plant families in South Africa, characterized by more than 100 species each [30]. Of the 125 species identified in this study (Table 2), 93 species (74.4%) were collected from the wild, while 26 species (20.8%) were cultivated and six species (4.8%) were spontaneous. More than a third of the plant species (37.6%) documented in this study are exotic to South Africa, while the remainder (62.4%) are native plants.

Plant use categories

Most of the identified species were used as herbal medicines (62.4%), followed by food plants (30.4%), ethnoveterinary medicine (18.4%), construction timber and thatching (11.2%) (Fig. 3). PRA exercises with participants revealed that TEK about food plants in the Eastern Cape province was much higher than medicinal plants and other use categories (Fig. 4). These results corroborate previous research by Turreira-García et al. [32] which revealed that food plants are characterized by high direct-use values as they are used by households on a daily basis, diversity of food plants provide households with important sources of nutrients, help to reduce the need of buying marketed alternatives and play an important role in achieving household food security. The majority of recorded plant species (70.4%) in the Eastern Cape province had only one use, 23.2% had two uses and 6.4% had at least three uses. Multipurpose plant species mentioned by at least 15% of the participants included Acacia karroo browsed by livestock and wild animals, used as ethnoveterinary medicine, firewood and herbal medicine, Aloe ferox (ethnoveterinary medicine, herbal medicine), Bulbine latifolia (ethnoveterinary medicine, herbal medicine), Capsicum annuum (edible fruits, herbal medicine), Citrus limon (edible fruits, herbal medicine), Elephantorrhiza elephantina (ethnoveterinary medicine, herbal medicine), Gunnera perpensa (ethnoveterinary medicine, herbal medicine), Opuntia ficus-indica (edible fruits, herbal medicine, ornamental) and Psidium guajava (edible fruits, herbal medicine). These results corroborate earlier research findings which recognized Acacia karroo [33], Aloe ferox [34], Bulbine latifolia [35], Capsicum annuum [36], Citrus limon [37], Elephantorrhiza elephantina [38], Gunnera perpensa [39], Opuntia ficus-indica [40] and Psidium guajava [41] as multipurpose plant species.

Medicinal plants

Plants used as ethnoveterinary and herbal medicines constituted 18.4% (23 species) and 62.4% (78 species) respectively of the total number of species recorded in this study. Plants used as ethnoveterinary and herbal medicines are culturally important plant use categories in the Eastern Cape province. The Xhosa people which constitute more than 80% of the population in the Eastern Cape province [21], is a cultural group known to use medicinal plants for cultural and religious practices [35, 42,43,44,45,46]. Previous research by Masika et al. [42] estimated that 75% of resource limited livestock farmers in the Eastern Cape province use traditional medicines to treat their animals and these farmers have a long history of treating and managing livestock diseases and ailments using ethnoveterinary medicines [43]. Masika and Afolayan [45] argued that this ethnoveterinary practice is an integral part of the Xhosa culture, a position that is unlikely to change to any significant degree in the coming years. About a third of species used as herbal medicines recorded in this study (30.8%) are highly valued medicinal plants in South Africa, their plant parts have potential in the development of new medicinal products with commercial value [47, 48], see Table 4. Therefore, some of plants used as herbal medicines in the Eastern Cape province have potential in the development of pharmaceutical products and drugs according to van Wyk [47] and van Wyk et al. [48]. Future research should attempt to correlate some of the documented ethnomedicinal uses of the species to their phytochemistry and pharmacological properties.

The plant parts used for preparing ethnoveterinary and herbal medicines were the bark, bulbs, fruits, leaf gel, leaves, rhizomes, roots, sap, seeds and whole plant (Table 2). The leaves were the most frequently used plant parts (50.6%), followed by roots and rhizomes (26.5%), bark (10.8%), bulb and leaf gel and sap (8.4% each), fruits and seed (3.6%) and whole plant (2.4%) (Fig. 5). However, harvesting of bark, bulbs, rhizomes, roots and whole plants is not sustainable, particularly if such harvested plants are herbaceous. Such harvesting methods threaten the survival of the same plants used to treat human and animal diseases and ailments in the Eastern Cape province. It is well recognized by conservationists that medicinal plants primarily valued for their root parts and those which are intensively harvested for their bark, bulbs, rhizomes, roots or whole plants uprooted often tend to be the most threatened by over-exploitation [49]. Eight species widely used as ethnoveterinary and herbal medicines (9.6%) in the Eastern Cape province are threatened with extinction mainly because they are over-exploited for traditional medicine trade [44, 50]. These species include Alepidea amatymbica, Boophone disticha, Bowiea volubilis ssp. volubilis, Clivia miniata, Gunnera perpensa, Hypoxis hemerocallidea, Ilex mitis and Prunus africana [50]. The IUCN Red List Categories and Criteria version 3.1 of threatened species (http://www.iucnredlist.org) was used by Raimondo et al. [50] to assess the conservation status of these eight species, categorizing Boophone disticha, Gunnera perpensa, Hypoxis hemerocallidea and Ilex mitis as declining, Alepidea amatymbica (Endangered, A2d), Bowiea volubilis ssp. volubilis (Vulnerable, VUA2ad), Clivia miniata (Vulnerable, A2abcd) and Prunus africana (Vulnerable, A4acd, C1 + 2ai). According to Victor and Keith [51] and von Staden et al. [52], a species categorized as Least Concern (LC) under the IUCN Red List Categories and Criteria version 3.1 can additionally be flagged as of conservation concern either as rare, critically rare or declining, hence Boophone disticha, Gunnera perpensa, Hypoxis hemerocallidea and Ilex mitis were categorized as declining by Raimondo et al. [50]. All these eight species which are threatened are also harvested for the medicinal plant trade in the Eastern Cape province [44]. Other species used as ethnoveterinary and herbal medicines that are traded in the Eastern Cape province herbal medicine (muthi) markets include: Asparagus africanus, A. asparagoides, Bulbine abyssinica, B. latifolia, Elephantorrhiza elephantina, Helichrysum odoratissimum, Pentanisia prunelloides ssp. prunelloides, Rhoicissus digitata, Tulbaghia alliacea and Xysmalobium undulatum [44].

The majority of the plant species used as herbal medicines (39.7%) had a single therapeutic use, with 20 species (25.6%) used in the treatment of two diseases, 11 species (14.1%) treating three diseases, ten species (12.8%) treating four diseases and four species (5.1%) treating at least five diseases or ailments (Table 2). A total of 38 medical conditions were treated using remedies made from medicinal plants documented in this study. Wounds and injuries, dermatological, cold, cough, sore throat and gastro-intestinal problems, tuberculosis (TB), cancer, pregnancy, birth and menstrual pain, abdominal pain and inflammations, headache, HIV and AIDS opportunistic infections, diabetes and sexually transmitted infections (STIs) were treated with the highest number of medicinal plant species (Fig. 6). High usage of traditional medicines against TB and HIV and AIDS opportunistic infections is not surprising as these are leading causes of death in the Eastern Cape province [53]. Recent research by Statistics South Africa [54] also revealed that TB, diabetes mellitus and HIV and AIDS opportunistic infections are among the top ten leading causes of death in South Africa. The use of herbal and alternative medicine is increasing in South Africa, it is estimated that about 27% of the population use herbal remidies [55]. Therefore, this inventory of herbal medicines used in the Eastern Cape is a crucial starting point in trying to identify widely used herbal medicines for primary health care in the management of human and animal diseases. Such plant species are important candidates for further research aimed at developing effective drugs and pharmaceutical products for the treatment and management of human and animal diseases and ailments. One of the possible approaches to finding novel therapeutic agents is the screening of medicinal plants that are widely used in local communities to treat and manage human and animal diseases and ailments.

Food plants

A variety of food plants were recorded in the Eastern Cape province, mainly edible fruits (21 species), leafy vegetables (10 species) and edible bulbs, roots or tubers (seven species) (Table 2). The majority of food plants documented in this study (71.1%) are exotic to South Africa (Table 2), widely cultivated in home gardens and agricultural fields in the Eastern Cape province as food plants. Exotic species which were collected from the wild included Amaranthus hybridus, Bidens pilosa, Chenopodium album, Sonchus asper, S. oleraceus and Taraxacum officinale (Table 2). Previous research by Jansen van Rensburg et al. [56, 57] and van der Hoeven et al. [58] showed that these five weedy species are widely collected as leafy vegetables in the wild in South Africa. With the exception of Centella coriacea, majority of indigenous food plants recorded in this study were fruit trees, which included Carissa bispinosa, Dovyalis caffra and Harpephyllum caffrum (Table 2). Some food plants such as Allium sativum, Bidens pilosa, Capsicum annuum, Centella coriacea, Citrus limon, Harpephyllum caffrum, Opuntia ficus-indica, Persea americana, Prunus persica and Psidium guajava were also used as herbal medicines. Important food plants mentioned by more than 20% of the participants included Allium cepa (onion), Brassica oleracea (cabbage), Capsicum annuum (pepper), Cucurbita maxima (pumpkin), Cucurbita moschata (butter-nut), Daucas carota (carrot), Ipomoea batatas (sweet potato), Lycopersicon esculentum (tomato), Opuntia ficus-indica (prickly pear), Phaseolus vulgaris (bean), Solanum tuberosum (potato), Spinacia oleracea (spinach) and Zea mays (maize). High frequencies associated with food plants in comparison with other plant use categories such as ethnoveterinary and herbal medicines (Fig. 4) corroborate research findings by Avila et al. [59] that the main purposes of agricultural environments of traditional communities is to produce food and the high agrobiodiversity found in these areas increases the nutritional diversity and quality of family diets.

Other plant use categories

Interviews with participants in the Eastern Cape province revealed that Acacia baileyana, A. caffra, A. dealbata, A. mearnsii, Bruguiera gymnorrhiza, Eucalyptus camaldulensis, E. grandis and Schotia latifolia were used to construct huts, fence and different types of enclosures (Table 2). Grass species which included Cymbopogon nardus, Hyparrhenia hirta, Miscanthus capensis, Phragmites australis, Sporobolus africanus and Sporobolus fimbriatus were harvested to thatch traditional structures such as huts and enclosures (Table 2). Five species, namely A. dealbata, A. karroo, A. mearnsii, Eucalyptus camaldulensis and E. grandis were used as fuelwood and for space heating. Previous research by Chirwa et al. [60] on bioenergy use in the Eastern Cape province revealed that despite the high level of electrification in the province, firewood is still used in most households for cooking while electricity was mostly used for lighting. These authors argued that firewood is preferred for cooking food that takes a long time to prepare, while more convenient sources of energy such as electricity is used for short periods of cooking and re-heating of food. Similarly, Dold and Cocks [44] argued that fuelwood is still preferred in the Eastern Cape province for cooking traditional leafy vegetables because of the particular flavour it adds. Research by Dold and Cocks [35] revealed that food prepared for religious rituals must always be cooked with fuelwood, notably Acacia karroo. Agave americana, Catharanthus roseus, Opuntia ficus-indica and Phoenix reclinata were cultivated as live fence and ornamental plants by some households (Table 2). Phoenix reclinata and Typha capensis were used for making crafts such as mats and baskets. Phoenix reclinata leaves were shredded and bound together to make brooms. Leaves of Acacia karroo, Combretum erythrophyllum, Cynodon dactylon and Diospyros lycioides were browsed by livestock, mainly cattle and goats.

Conclusion

PRA exercises with participants and observations made on main livelihood attributes in the study area seem to suggest that the TEK, practices and beliefs of the Xhosa people are dynamic and adaptive. This can be seen in the incorporation of exotic plant species to South Africa in the indigenous pharmacopoeia and indigenous diet of local people in the Eastern Cape province. Some exotic plants which are now part of the indigenous pharmacopoeia in the study area include Agave americana, Catharanthus roseus, Ficus carica, Opuntia ficus-indica, Psidium guajava and Sonchus asper. Research by Palmer [61] argued that the medicinal plant composition of a community is the product of experimentations conducted throughout the history of a community and represents an adaptation of this culture over time. While Alencar et al. [62] argued that any indigenous medical system is not a static social institution that is not evolving, as there is evidence of insertions and deletions of plants that compose it, with the addition of exotic plants as herbal medicines. Therefore, results of the current study corroborate an earlier observation that TEK systems are a reservoir of experiential knowledge that can provide important insights for the design of adaptation and mitigation strategies to cope with global environmental change [63].

References

MEA (Millennium Ecosystem Assessment): Ecosystems and human well-being: a framework for assessment. Washington DC: Island Press; 2003.

Khan SM, Page SE, Ahmad H, Harper DM. Sustainable utilization and conservation of plant biodiversity in montane ecosystems: the western Himalayas as a case study. Annals Bot. 2013;112:479–501.

Uprety Y, Poudel RC, Shrestha KK, Rajbhandary S, Tiwari NN, Shrestha UB, Asselin H. Diversity of use and local knowledge of wild edible plant resources in Nepal. J Ethnobiol Ethnomed. 2012;8:16.

Sunderland TCH. Food security: why is biodiversity important? Int Forestry Rev. 2011;13:265–74.

Bruyere BL, Trimarco J, Lemungesi S. A comparison of traditional plant knowledge between students and herders in northern Kenya. J Ethnobiol Ethnomed. 2016;12:48.

Maroyi A, Cheikhyoussef A. Traditional knowledge of wild edible fruits in southern Africa: comparative use patterns in Namibia and Zimbabwe. Indian J Trad Knowl. 2017;16:385–92.

Roué M, Césard N, Yao YCA, Oteng-Yeboah A: Knowing our lands and resources: indigenous and local knowledge of biodiversity and ecosystem services in Africa. Paris: Knowledges of Nature 8, UNESCO; 2017.

Ketlhoilwe MJ, Jeremiah K. The role of traditional ecological knowledge in natural resources management: a case study of village communities in eastern part of Botswana. European J Ed Stud. 2016;2:29–43.

Maroyi A, Rasethe MT. Comparative use patterns of plant resources in rural areas of South Africa and Zimbabwe. Phyton: Int J Exp Bot. 2015;84:288–97.

Rim-Rukeh A, Irerhievwie G, Agbozu IE. Traditional beliefs and conservation of natural resources: evidences from selected communities in Delta state, Nigeria. Int J Biod Cons. 2013;5:426–32.

Mannetti L. Understanding plant resource use by the ≠Khomani bushmen of the southern Kalahari. MSc dissertation. Cape Town: University of Stellenbosch; 2011.

Berkes F, Colding J, Folke C. Rediscovery of traditional ecological knowledge as adaptive management. Ecol Appl. 2000;10:1251–62.

Harisha RP, Padmavathy S, Nagaraja BC. Traditional ecological knowledge (TEK) and its importance in south India: perspecive from local communities. Appl Ecol Environmental Res. 2016;14:311–26.

Irakiza R, Vedaste M, Elias B, Nyirambangutse B, Serge NJ, Marc N. Assessment of traditional ecological knowledge and beliefs in the utilisation of important plant species: the case of Buhanga sacred forest. Rwanda Koedoe. 2016;58:1.

van Wyk B-E, Gericke N. People’s plants: A guide to useful plants of Southern Africa. Pretoria: Briza Publications; 2007.

ECSECC (Eastern Cape Socio Economic Consultative Council): Eastern Cape socio-economic atlas 2012: a visual tour of the Eastern Cape physical and social terrain; 2012. Http: www.ecsecc.org.

Westaway A. Rural poverty in the eastern Cape Province: legacy of apartheid or consequence of contemporary segregation? Develop Southern Afr. 2012;29:115–25.

Thornton A. Pastures of plenty? Land rights and community-based agriculture in Peddie, a former homeland town in South Africa. Appl Geogr. 2009;29:12–20.

Hebinck P, Lent P. Livelihoods and landscape: the people of Guquka and Koloni and their resources. Leiden/Boston: Brill Academic Publishers; 2007.

Shackleton CM, Timmermans HG, Nongwe N, Hamer N, Palmer RCG. Direst-use value of non-timber forest products from two areas on the Transkei wild coast. Agrekon. 2007;46:135–55.

Hamann M, Tuinder V. Introducing the eastern cape: a quick guide to its history, diversity and future challenges. Stockholm: Stockholm Resilience Centre, Stockholm University; 2012.

Chalmers N, Fabricius C. Expert and generalist local knowledge about land-cover change on South Africa’s wild coast: can local ecological knowledge add value to science? Ecol Soc. 2007;12:10.

Mucina L, Rutherford MC. The Vegetation of South Africa, Lesotho and Swaziland. Strelizia 19. Pretoria: South African National Biodiversity Institute; 2006.

Palmer R, Timmermans H, Fay D. From conflict to negotiation: nature-based development on South Africa’s wild coast. Human Science Research Council: Grahamstown; 2000.

Jari B, GCG F. Unlocking markets to smallholders: lessons from South Africa. In: van Schalkwyk HD, Groenewald JA, GCG F, Obi A, van Tilburg A, editors. Influence of institutional and technical factors on market choices of smallholder farmers in the Kat River valley. Wageningen: Wageningen Academic Press; 2012. p. 59–89.

Manyevere A, Muchaonyerwa P, Laker MC, Mnkeni PNS. Farmers’ perspectives with regard to crop production: an analysis of Nkonkobe municipality, South Africa. J Agr Rural Develop Tropics Subtropics. 2014;115:41–53.

Chambers R. The origins and practice of participatory rural appraisal (PRA). World Develop. 1994;22:953–69.

Cunningham AB. Applied ethnobotany: people, wild plant use and conservation. Sterling, VA: Earthscan Publications; 2001.

Miles MB, Huberman AM. Qualitative data analysis: an expanded source book. 2nd ed. London: Sage; 1994.

Germishuizen G, Meyer NL, Steenkamp Y, Keith M: A checklist of South African plants. Pretoria: Southern African Botanical Diversity Network Report (SABONET) No. 41; 2006.

Hammer Ø, Harper DAT, Ryan RD. PAST: palaeontological statistics software package for education and data analysis. Palaeontol Electron. 2001;4:1–9.

Turreira-García N, Theilade I, Meilby H, Sørensen M. Wild edible plant knowledge, distribution and transmission: a case study of the Achí Mayans of Guatemala. J Ethnobiol Ethnomed. 2015;11:52.

Maroyi A. Acacia karroo Hayne: Ethnomedicinal uses, phytochemistry and pharmacology of an important medicinal plant in southern Africa. Asian Pacific J Trop Med. 2017;10:351–60.

Chen W, van Wyk B-E, Vermaak I, Viljoen AM. Cape aloes: a review of the phytochemistry, pharmacology and commercialisation of Aloe ferox. Phytochem Lett. 2012;5:1–12.

Dold T, Cocks M: Voices from the forest: celebrating nature and culture in Xhosaland. Johannesburg: Jacana Media (Pty) Ltd; 2012.

Grubben GJH, El Tahir IM. In: GJH G, Denton OA, editors. Capsicum annuum L. in Plant resources of tropical Africa 2: vegetables. Wageningen: PROTA Foundation, Backhuys Publishers; 2004. p. 154–63.

Rao MR, Rajeswara Rao RB. In: Kumar BM, PKR N, editors. Medicinal plants in tropical homegardens. In Tropical homegardens: a time-tested example of sustainable agroforestry. Dordrecht: Springer; 2006. p. 205–32.

Maroyi A. Elephantorrhiza elephantina: traditional uses, phytochemistry and pharmacology of an important medicinal plant species in southern Africa. Evidence-Based Compl Altern Med. 2017:6856154. doi:10.1155/2017/6403905.

Maroyi A. From traditional usage to pharmacological evidence: systematic review of Gunnera perpensa L. Evidence-Based Compl Altern Med. 2016;Volume 2016:1720123.

Brutsch MO, Zimmermann HG. The prickly pear (Opuntia Ficus-Indica [Cactaceae]) in South Africa: utilization of the naturalized weed, and of the cultivated plant. Econ Bot. 1993;47:154–62.

Sharma S, Rajat K, Prasad R, Vasuderian P. Biology and potencial of Psidium guajava. J Sci Industrial Res. 1999;58:414–21.

Masika PJ, van Averbeke W, Sonandi A. Use of herbal remedies by small-scale farmers to treat livestock diseases in the eastern Cape Province, South Africa. J S Afri Vet Ass. 2000;71:87–91.

Dold AP, Cocks ML. Traditional veterinary medicine in the Alice district of the eastern Cape Province, South Africa. S Afr J Sci. 2001;97:1–5.

Dold AP, Cocks ML. The trade in medicinal plants in the eastern Cape Province, South Africa. S Afr J Sci. 2002;98:589–97.

Masika PJ, Afolayan AJ. An ethnobotanical study of plants used for the treatment of livestock diseases in the eastern Cape Province, South Africa. Pharm Biol. 2003;41:16–21.

Bhat RB. Medicinal plants and traditional practices of Xhosa people in the Transkei region of eastern cape, South Africa. Indian J Trad Knowl. 2014;13:292–8.

van Wyk B-E. The potential of south African plants in the development of new medicinal products. S Afr J Bot. 2011;77:812–29.

van Wyk B-E, van Oudtshoorn B, Gericke N. Medicinal plants of South Africa. Pretoria: Briza Publications; 2013.

Mander M, Ntuli L, Diedrichs N, Mavundla K. Economics of the traditional medicine trade in South Africa. FutureWorks Report for Ezemvelo KZN Wildlife: Durban; 2007.

Raimondo D, von Staden L, Foden W, Victor JE, Helme NA, Turner RC, Kamundi DA, Manyama PA: Red list of South African plants. Pretoria: Strelitzia 25, South African National Biodiversity Institute, Pretoria; 2009.

Victor JE, Keith M. The orange list: a safety net for biodiversity in South Africa. S Afr J Sci. 2004;100:139–41.

von Staden L, Raimondo D, Foden W. Red list of south African plants. In: Raimondo D, von Staden L, Foden W, Victor JE, Helme NA, Turner RC, Kamundi DA, Manyama PA, editors. Approach to red list assessments. Pretoria: Strelitzia 25, South African National Biodiversity Institute; 2009. p. 6–16.

Makiwane MB, Chimere-Dan DOB. The people matter: the state of the population in the eastern cape. Research and Population Unit, Eastern Cape Department of Social Development: East London; 2010.

Statistics South Africa. Mortality and causes of death in South Africa, 2015: findings from death notification. Pretoria: Government Printers; 2017.

Afolayan AJ, Sunmono TO. In vivo studies on antidiabetic plants used in south African herbal medicine. J Clin Biochem Nutr. 2010;47:98–106.

Jansen van Rensburg WS, Cloete M, Gerrano AS, Adebola PO. Have you considered eating your weeds? American J Pl Sci. 2014;5:1110–6.

Jansen van Rensburg WS, van Averbeke W, Slabbert R, Faber M, van Jaarsveld P, van Heerden I, Wenhold F, Oelofse A. African leafy vegetables in South Africa. Water SA. 2007;33:317–26.

van der Hoeven M, Osei J, Greeff M, Kruger A, Faber M, Smuts CM. Indigenous and traditional plants: south African parents’ knowledge, perceptions and uses and their children’s sensory acceptance. J Ethnobiol Ethnomed. 2013;9:78.

Ávila JVC, de Mello AS, Beretta ME, Trevisan R, Fiaschi P, Hanazaki N. Agrobiodiversity and in situ conservation in Quilombola home gardens with different intensities of urbanization. Acta Bot Brasilica. 2017;31:1–10.

Chirwa PW, Ham C, Maphiri S. Bioenergy use and food preparation practices of two communities in the eastern Cape Province of South Africa. J Energy Southern Afr. 2010;21:26–31.

Palmer CT. The inclusion of recently introduced plants in the Hawaiian ethnopharmacopoeia. Econ Bot. 2004;58:280–93.

Alencar NL, Santoro FR, Albuquerque UP. What is the role of exotic medicinal plants in local medical systems? A study from the perspective of utilitarian redundancy. Revista Bras Farmacog. 2014;24:506–15.

Gómez-Baggethun E, Corbera E, Reyes-Garcia V. Traditional ecological knowledge and global environmental change: research findings and policy implications. Ecol Soc. 2013;18:72.

Acknowledgements

Matthew Mamera, Pelisa Ngcaba, Mercy H Nqandeka, Mandla Nxele, Thabo Ntabeni and Keith Obose assisted with field work and data gathering.

Funding

The author would like to express his gratitude to the Water Research Commission (WRC), National Research Foundation (NRF) and Govan Mbeki Research and Development Centre (GMRDC), University of Fort Hare for financial support to conduct this research.

Availability of data and materials

Raw data is contained in questionnaire forms and cannot be shared in this form.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

This study was approved by the University of Fort Hare’s Research Ethics Committee (UREC) on 25 February 2014, and ethics clearance code is MAR011. Before conducting interviews, all participants signed the prior informed consent form.

Consent for publication

This manuscript does not contain any individual person’s data and therefore, no further consent is required for publication.

Competing interests

The author declares that he has no conflict of interest.

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made. The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver (http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/) applies to the data made available in this article, unless otherwise stated.

About this article

Cite this article

Maroyi, A. Diversity of use and local knowledge of wild and cultivated plants in the Eastern Cape province, South Africa. J Ethnobiology Ethnomedicine 13, 43 (2017). https://doi.org/10.1186/s13002-017-0173-8

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s13002-017-0173-8