Abstract

Background

The clinicopathological features and Epstein-Barr virus (EBV) infection status of lymphoma in children and adolescents in South China is under-researched. South China is a well-known high-incidence area of EBV-associated nasopharyngeal carcinoma.

Methods

A cohort of 662 consecutive children and adolescents’ lymphomas was retrospectively analyzed and Epstein-Barr virus encoded RNAs (EBERs) in situ hybridization was performed to detect the EBV infection.

Results

The majority (501/662, 75.7%) of lymphomas in children and adolescents was Non-Hodgkin lymphoma (NHL). One hundred sixty one cases (24.3%) were Hodgkin lymphoma (HL). Of the NHL, precursor cell lymphoma, mature B-cell lymphoma and peripheral T/NK-cell lymphoma accounted for 32.0%, 41.1% and 26.9% respectively. The five common subtypes were lymphoblastic lymphoma (32.0%), Burkitt lymphoma (BL) (21.0%), anaplastic large-cell lymphoma (ALCL) (14.2%), diffuse large B-cell lymphoma (DLBCL) (13.8%) and extranodal NK/T-cell lymphoma, nasal type (ENKTCL) (6.2%). EBV infection was detected in 58.9% classical Hodgkin lymphomas (CHLs), 21.4% mature B-cell lymphomas and 52.4% peripheral T/NK-cell lymphomas. Moreover, EBV was associated with high grade NHL including ENKTCL (100.0%), BL (30.5%) and DLBCL (17.6%).

Conclusion

The high proportion of peripheral T/NK-cell lymphomas in children and adolescents in South China are presented in this study and compared to western countries due to the high percentage of ENKTCL. ENKTCL is firmly associated with EBV infection, while more than half of HL, a portion of BL and DLBCL are related to EBV infection. This study conclusively demonstrates that EBV infection is more prevalent in children and adolescents with lymphomas in South China compared to western countries.

Similar content being viewed by others

Background

Lymphoid neoplasms are the most common neoplasms in children and adolescents worldwide and represent a major cause of tumor death in China [1, 2]. Generally, malignant lymphomas have been grouped into two categories: Hodgkin’s lymphoma (HL) and Non-Hodgkin’s lymphoma (NHL). HL is one of the most curable forms of cancer with an estimated 5-year survival rate exceeding 98% [3]. However, NHL is more complex and has been classified by the World Health Organization (WHO) based on phenotype (B vs T vs NK-cell lineage) and differentiation (i.e. Precursor vs mature) [4].

Most reports of NHLs in children and adolescents are high grade lymphomas, including Burkitt’s lymphoma (BL), diffuse large B-cell lymphoma (DLBCL), lymphoblastic lymphoma (LBL) and anaplastic large cell lymphoma (ALCL) [5,6,7]. The occurrence and clinicopathologic features of low grade lymphomas in children and adolescents have not been well characterized and are not up to date.

It is well established that Epstein-Barr virus (EBV) plays an important role in some subtypes of lymphomas, such as CHL, extranodal NK/T cell lymphoma (ENKTCL) and BL [8,9,10]. In addition, South China is a high-incidence area of EBV-associated nasopharyngeal carcinoma, thus the clinicopathological features and Epstein-Barr virus (EBV) infection status of lymphoma in children and adolescents in South China is worthy of investigation. In this study, a cohort of 662 consecutive lymphomas in children and adolescents were retrospectively analyzed in which Epstein-Barr virus encoded RNAs (EBERs) in situ hybridization was performed to detect EBV infection.

Methods

Patient selection

A total of 662 cases of lymphoma in children and adolescents (≦20 years old) were obtained retrospectively from the Department of Pathology at Sun Yat-sen University Cancer Center during the period of January 2010 to January 2014. A diagnostic criterion was established according to the 4th revised edition of the WHO classification of Tumours of Haematopoietic and Lymphoid Tissues [11]. Diagnosis was confirmed by two hematopathologists.

Clinical characteristics analysis

The clinical data, including gender, age, and tumor localization (biopsy site) were analyzed. Slides and images were reviewed including biopsy of the lymph node or mass, computed tomography (CT) scan of the chest, abdominopelvic ultraso-nography, and bone marrow biopsies in selected cases.

Distribution of lymphoma subtypes and EBV detection

The data were available on a standard panel of immunochemistry stains using antibody anti-CD20, CD79, PAX-5, CD2, CD3, CD4, CD5, CD7, CD8, CD30, CD56, CD15, ALK (anaplastic large cell lymphoma kinase), and on a fluorescence in situ hybridization (FISH) for the chromosomal translocation juxtaposing the c-myc oncogene and immunoglobulin locus regulatory element of it (8;14) in the dedicated diagnosis of BL [12]. IgH and/or TCR gene rearrangement detection using polymerase chain reaction (PCR) was performed in the diagnosis of uncertain cases by routine histopathologic and immunophenotypic evaluation. Subtype distribution of lymphoma was analyzed according to the WHO criteria. EBV was detected using the EBV Probe In Situ Hybridization Kit (TRIPLEX INTERNATIONAL BIOSCIENCES, CHINA, CO. LTD).

Statistical analysis

Data were statistically described using means±standard deviation (SD), range, frequencies (number of cases) and percentages when appropriate. All statistical calculations were carried out using the Statistical Package for the Social Sciences software (SPSS), version 19.

Results

Clinical features

The median age was 13 years old and the ratio of male to female was 1.68:1. Most lymphomas showed a male predominance including classical Hodgkin’s lymphoma (CHL) (M/F = 1.68), BL (M/F = 5.56), ALCL (M/F = 1.84) and LBCL (M/F = 1.47), while ENKTCL showed a slight female predominance (M/F = 0.82) (Additional file 1: Table S1 and Table 1).

The biopsy site of HL in children and adolescent was assessed in this study. Most HL occurred in the lymph node (Table 2). Extranodal site involvement in HL was uncommon (Table 2). 59.6% of NHL presented an extranodal site involvement at the time of diagnosis. The most common extranodal site of NHL involved the gastrointestinal tract (GI) (32.8%), skin (17.2%) and areas of the head and neck (16.2%) (Table 3).

Subtype distribution of lymphoma in children and adolescents

The majority (501/662, 75.7%) of lymphoma were NHL (Additional file 1: Table S1). One hundred sixty one cases (24.3%) were HL (Table 1). Of the NHL, the proportion of precursor cell lymphomas (TLBL/BLBL) was 32.0%, while the proportion of mature B-cell lymphomas and peripheral T/NK-cell lymphomas was 41.1% and 26.9%, respectively. The five common NHLs observed in children and adolescents were LBL (32.0%), BL (21.0%), ALCL (14.2%), DLBCL (13.8%) and ENKTCL (6.2%).

EBV infection status of lymphoma in children and adolescents

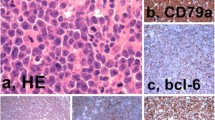

Ninety seven HLs were detected by EBERs in situ hybridization in this study, including 90 cases of CHL and 7 cases of Nodular lymphocyte predominant Hodgkin lymphoma (NLPHL). 58.9% cases of CHL (53/90) were EBV positive. No cases (0/7) of NLPHL were positive for EBERs. Among CHLs, mixed cellularity classical Hodgkin lymphoma (MC-CHL) showed the highest rate of positivity for EBERs (20/26, 76.9%), followed by Lymphocyte-rich classical Hodgkin lymphoma (LR-CHL) (11/16, 68.8%) (Table 1, Fig. 1). We also detected EBV in 256 NHLs, including 60 cases of LBL, 112 cases of mature B-cell lymphomas as well as 84 cases of peripheral T/NK-cell lymphomas. EBV infection was detected in 21.4% of mature B-cell lymphomas and 52.4% of peripheral T/NK-cell lymphomas. Hydroa vacciniforme-like lymphoproliferative disease (HVLLPD) also showed a strong association with EBV infection (11/11, 100%) (Additional file 1: Table S1). EBV was associated with high grade NHL including ENKTCL (100.0%), BL (30.5%) and DLBCL (17.6%) (Table 4, Fig. 2, Fig. 3, Fig. 4). No EBV infection was detected in ALCL (0/28). All lymphoblastic lymphomas were negative for EBERs (0/60).

EBV infection in CHL (NS type) in children and young adolescents. a Mononuclear Hodgkin cells and mutinucleated Reed-Sternberg cells are seen in a cellular background rich in lymphocytes and some eosinophils (H&E, 400x). The neoplastic cells are positive for PAX-5 (b), CD30 (c) and EBERS in situ hybridization (d)

Discussion

Lymphoid neoplasms represent the dominant type of malignancy in children and adolescents worldwide, with the distribution of subtypes varying geographically. Major progression has been made in understanding the pathological characteristics of lymphoid neoplasms in the last 5 years, hence the WHO’s expanded spectrum of EBV related lymphomas [9, 10].

The population of South China is believed to have been be exposed to, or have a genetic susceptibility to EBV [13]. In this study, the clinicopathological features and EBV infection status of 662 cases of children and adolescents with lymphoma in South China were reviewed and analyzed.

The proportion of HL in children and adolescents in this study is 24.3% higher than that observed in western countries (11%-15%) [14]. Most HL patients showed lymphadenopathy which coordinates with other published data [15]. However, the majority of children and adolescents’ lymphomas was NHL. More than half of NHL (59.6%) patients were presented with extranodal site involvement at diagnosis which might make it difficult to detect the disease at an earlier stage [6].

Distribution of lymphoma subtypes is presented in this report. Compared to adult lymphoma MC-CHL has been reported as the most common subtype of CHL [2], in this study of children and adolescents, nodular sclerosis type CHL (NS-CHL) was more frequent than other subtypes of CHL, which is consistent with reports from other areas [7]. Peripheral T/NK cell lymphomas comprised of 26.9% of NHLs in South China, which is higher than that observed in western countries (15%-20%) [11]. LBL has been reported as the most common lymphoid neoplasms in children and adolescents (32.0% of NHLs in this study) with the dominant type of TLBL (70.0% in this study) [16]. BL accounted for 21.0% of NHLs, similar to other reports in western countries (20.0%-40.0%) [17], but it occurred more frequently compared to other areas of Asia (9-12%) [6]. The incidence of anaplastic large-cell lymphoma (ALCL) differs significantly worldwide (2%-20%) [6, 18]. In this study, ALCL was the third most common NHL in children and adolescents. Moreover, ENKTCL accounted for 22.9% of peripheral T/NK-cell lymphomas, indicating its prevalence in areas of East Asia [10, 19, 20]. HVLLPD, the nomenclature and definition changed from hydroa vacciniforme-like lymphoma (HVLL) to lymphoproliferative disorder due to its relationship with chronic active EBV infection and clinical course, comprised 8.1% of mature T/NK-cell neoplasms in this study. HVLLPD is extremely rare in western countries. Recurrent skin lesions with T-cell or NK-cell type in children and adolescents from Asian and Latin American countries have been described [11, 21]. Our data suggest CAEBV of T/NK-cell, perhaps persists only in genetically predisposed individuals.

Significant advancement in recent years has been made in better understanding MYC alterations of DLBCL [22] and the updated WHO classification of high grade B-cell lymphoma [11, 23]. Clinically, DLBCL in young patients is very aggressive and commonly treated with similar regimens to BL [24]. The proportion of this kind of lymphoma in our research is 13.8% which is similar to results found in the literature [16].

EBV is a ubiquitous lymphotropic gammaherpesvirus that infects > 90% of the world population, usually without adverse health consequences. However, EBV is associated with malignancies of B-cell origin, NK/T-cell origin, and epithelial malignancies, such as endemic BL, ENKTCL, HL and nasopharyngeal carcinoma (NPC).

The pooled prevalence of EBV infection in CHLs of children and adolescents was 58.9% in this study which was higher than that reported in western countries (fewer than 40%) [25, 26]. Specifically, EBV infection was detected in MC-CHL (76.9%), followed by lymphocyte-rich LR-CHL (75.0%) and NS-CHL type (44.7%). EBV infection showed no association with NLPHL which is in accordance with other reports [27].

The role of EBV in the pathogenesis of NHL has been observed in this study, 52.4% of peripheral T/NK-cell lymphomas and 21.4% of mature B-cell lymphomas were EBV positive. Moreover, EBV was associated with high grade NHL including ENKTCL, BL and DLBCL. No EBV was detected in LBL or ALCL.

It has been consistently documented that ENKTCL is associated with EBV infection [28, 29]. Other risk factors and the pathogenesis of ENKTCL are not well understood. Recently, a major breakthrough in the field of genetic research for ENKTCL has been found from southern China. The study shows that the susceptibility gene of ENKTCL is the HLA-DPB1 gene, suggesting that ENKTCL have distinct pathogenic mechanisms with NPC or HL [30].

The possible contribution of EBV to BL pathogenesis is mainly unknown. In one hypothesis, it has been suggested that EBV may be associated with all of the cases by a mechanism of hit-and-run [31]. Early during oncogenesis, viral genes potentiate tumor development. Progressively, viral genome is lost to escape the immune system, and proto-oncogene mutations promote tumor progression. The expression of EBV-encoded miRNAs by miRNA profiling can be observed in BL case including EBERs negative cases [32]. The “hit and run” model could explain why some cases of endemic BL are negative for latent EBV genomes.

EBV can be detected in more than 95% of endemic BL cases and approximately 20-30% of sporadic BL by EBERs. Molecular profiles and significant pathways of endemic BL and sporadic BL are different [33]. Endemic and HIV-related BL cases may derive from a later developmental stage of B cells, i.e. post-germinal centre/memory B cells [34]. In sporadic BL, the intrinsic activation of BCR pathway due to the mutations of TCF3/ID3 genes may further allow neoplastic cells to grow with or without EBV [35].

EBV related BL is more prevalent in this study (30.5%) compared to that of western countries [36]. The higher prevalence of EBV positive BL cases in children and adolescents in South China might result from early EBV infection [37].

EBV-positive DLBCL has been observed in younger patients and led to substituting the modified “elderly” with “not otherwise specified” (EBV+ DLBCL, NOS) in the updated classification [38]. The incidence of EBV infection among DLBCL from Asian or Latin American patients (elderly) ranges from 8% to 15%, less than 5% in western countries [39]. Our study showes the incidence of EBV infection in DLBCL in children and adolescents was 17.6%. Yet, further studies are needed to explore whether this incidence is different from that of adults in South China.

Conclusions

The high proportion of peripheral T/NK-cell lymphomas in children and adolescents in South China is presented in this study and compared to western countries due to the high percentage of ENKTCL. ENKTCL is firmly associated with EBV infection, while more than half of HL, a portion of BL and DLBCL are related to EBV infection. This study conclusively demonstrates that EBV infection is more prevalent in children and adolescents with lymphomas in South China compared to western countries.

Abbreviations

- ALCL:

-

Anaplastic large-cell lymphoma

- ALK:

-

Anaplastic large cell lymphoma kinase

- BL:

-

Burkitt lymphoma

- CHL:

-

Classical Hodgkin lymphoma

- CHL-LD:

-

Lymphocyte-depleted classical Hodgkin lymphoma

- CHL-LR:

-

Lymphocyte-rich classical Hodgkin lymphoma

- CHL-MC:

-

Mixed cellularity classical Hodgkin lymphoma

- CHL-NS:

-

Nodular sclerosis classical Hodgkin lymphoma

- CT:

-

Computed tomography

- DLBCL:

-

Diffuse large B cell lymphoma

- EBERS:

-

In situ hybridization for Epstein-Barr virus encoded RNAs

- EBV:

-

Epstein Barr virus

- ENKTCL:

-

Extranodal NK/T-cell lymphoma, nasal type

- HL:

-

Hodgkin lymphoma

- HVLLPD:

-

Hydro vaceinifomle-like cutaneous T-cell lymphoproliferative disorders/lymphoma

- NHL:

-

Non-Hodgkin lymphoma

- NLPHL:

-

Nodular lymphocyte predominant Hodgkin lymphoma

- NPC:

-

Nasopharyngeal carcinoma

- TLBL/BLBL:

-

Lymphoblastic lymphoma (precursor T-and precursor B-cell lymphoma

- WHO:

-

The World Health Organization

References

Linet MS, Brown LM, Mbulaiteye SM, et al. International long-term trends and recent patterns in the incidence of leukemias and lymphomas among children and adolescents ages 0-19 years. Int J Cancer. 2016;138:1862–74.

Yang QP, Zhang WY, Yu JB, et al. Subtype distribution of lymphomas in Southwest China: analysis of 6,382 cases using WHO classification in a single institution. Diagn Pathol. 2011;6:77.

Castellino SM, Geiger AM, Mertens AC, et al. Morbidity and mortality in long-term survivors of Hodgkin lymphoma: a report from the childhood cancer survivor study. Blood. 2011;117:1806–16.

Jaffe ES, Harris NL, Stein H, et al. Classification of lymphoid neoplasms: the microscope as a tool for disease discovery. Blood. 2008;112:4384–99.

Sherief LM, Elsafy UR, Abdelkhalek ER, et al. Disease patterns of pediatric non-Hodgkin lymphoma: a study from a developing area in Egypt. Mol Clin Oncol. 2015;3:139–44.

Allen CE, Kelly KM, Bollard CM. Pediatric lymphomas and Histiocytic disorders of childhood. Pediatr Clin N Am. 2015;62:139–65.

Sandlund JT, Martin MG. Non-Hodgkin lymphoma across the pediatric and adolescent and young adult age spectrum.Hematology am soc Hematol Educ program. Hematology Am Soc Hematol Educ Program. 2016;2016:589–97.

Dojcinov SD, Venkataraman G, Pittaluga S, et al. Age-related EBV-associated lymphoproliferative disorders in the western population: a spectrum of reactive lymphoid hyperplasia and lymphoma. Blood. 2011;117:4726–35.

Said J. The expanding spectrum of EBV+ lymphomas. Blood. 2015;126:827–8.

Vose J, Armitage J, Weisenburger D. International peripheral T-cell and natural killer/T-cell lymphoma study: pathology findings and clinical outcomes. J Clin Oncol. 2008;26:4124–30.

Swerdlow SH, Campo E, Harris NL, et al. WHO classification of Tumours of Haematopoietic and lymphoid tissues (IARC WHO classification of Tumours) revised 4th edition. Lyon: IARC Press; 2017.

Love C, Sun Z, Jima D, et al. The genetic landscape of mutations in Burkitt lymphoma. Nat Genet. 2012;44:1321–5.

Young LS, Yap LF, Murray PG. Epstein-Barr virus: more than 50 years old and still providing surprises. Nat Rev Cancer. 2016;16:789–802.

Bigenwald C, Galimard J-E, Quero L, et al. Hodgkin lymphoma in adolescent and young adults: insights from an adult tertiary single-center cohort of 349 patients. Oncotarget. 2017;8:80073–82.

Ambrosio MR, Rocca BJ, Barone A, et al. Primary anorectal Hodgkin lymphoma: report of a case and review of the literature. Hum Pathol. 2014;45:648–52.

Minard Colin V, Brugières L, Reiter A, et al. Non-Hodgkin lymphoma in children and adolescents: progress through effective collaboration, current knowledge, and challenges ahead. J Clin Oncol. 2015;33:2963–74.

Miles RR, Arnold S, Cairo MS. Risk factors and treatment of childhood and adolescent Burkitt lymphoma/leukaemia. Br J Haematol. 2012;156:730–43.

Han JY, Suh JK, Lee SW, et al. Clinical characteristics and treatment outcomes of children with anaplastic large cell lymphoma: a single center experience. Blood Res. 2014;49:246–52.

Anonymous. The world health organization classification of malignant lymphomas in Japan: incidence of recently recognized entities. Lymphoma study Group of Japanese Pathologists. Pathol Int. 2000;50:696–702.

Pillai V, Tallarico M, Bishop MR, et al. Mature T- and NK-cell non-Hodgkin lymphoma in children and young adolescents. Br J Haematol. 2016;173:573–81.

Quintanilla-Martinez L, Ridaura C, Nagl F, et al. Hydroa vacciniforme-like lymphoma: a chronic EBV+ lymphoproliferative disorder with risk to develop a systemic lymphoma. Blood. 2013;122(18):3101–10.

Karube K, Campo E. MYC alterations in diffuse large B-cell lymphomas. Semin Hematol. 2015;52:97–106.

Swerdlow SH. Diagnosis of ‘double hit’ diffuse large B-cell lymphoma and B-cell lymphoma, unclassifiable, with features intermediate between DLBCL and Burkitt lymphoma: when and how, FISH versus IHC. Hematology Am Soc Hematol Educ Program. 2014;2014:90–9.

Oschlies I, Burkhardt B, Salaverria I, et al. Clinical, pathological and genetic features of primary mediastinal large B-cell lymphomas and mediastinal gray zone lymphomas in children. Haematologica. 2011;96:262–8.

Armstrong AA, Alexander FE, Paes RP, etal. Association of Epstein-Barr Virus with pediatric hodgkin' disease. AM J Pathol. 1993;142(6):1683–8.

Lee JH, Kim Y, Choi JW, et al. Prevalence and prognostic significance of Epstein-Barr virus infection in classical Hodgkin'slymphoma: a meta-analysis. Arch Med Res. 2014;45:417–31.

Huppmann AR, Nicolae A, Slack GW, et al. EBV may be expressed in the LP cells of nodular lymphocyte-predominant Hodgkin lymphoma (NLPHL) in both children and adults. Am J Surg Pathol. 2014;38:316–24.

Zaheen A, Delabie J, Vajpeyi R, et al. The first report of a previously undescribed EBV-negative NK-cell lymphoma of the GI tract presenting as chronic diarrhoea with eosinophilia. BMJ Case Rep. 2015;2015 https://doi.org/10.1136/bcr-2015-212103.

Chiang AK, Chan AC, Srivastava G, et al. Nasal T/natural killer (NK) -cell lymphomas are derived from Epstein-Barr virus-infected cytotoxic lymphocytes of both NK- and T-cell lineage. Int J Cancer. 1997;73:332–8.

Li Z, Xia Y, Feng LN, et al. Genetic risk of extranodal natural killer T-cell lymphoma: a genome-wide association study. Lancet Oncol. 2016;17:1240–7.

Ambinder RF. Gammaherpesviruses and “hit-and-run”Oncogenesis. Am J Pathol. 2000;156:1–3.

Mundo L, Ambrosio MR, Picciolini M, et al. Unveiling another missing piece in EBV-driven Lymphomagenesis: EBV-encoded MicroRNAs expression in EBER-negative Burkitt lymphoma cases. Front Microbiol. 2017;8:229.

Ambrosio MR, Lo Bello G, Amato T, et al. The cell of origin of Burkitt lymphoma: germinal centre or not germinal centre? Histopathology. 2016;69:885–6.

Abate F, Ambrosio MR, Mundo L, et al. Distinct viral and mutational Spectrum of endemic Burkitt lymphoma. PLoS Pathog. 2015;11(10):e1005158.

Amato T, Abate F, Piccaluga P, et al. Clonality analysis of immunoglobulin gene rearrangement by next-generation sequencing in endemic Burkitt lymphoma suggests antigen drive activation of BCR as opposed to sporadic Burkitt lymphoma. Am J Clin Pathol. 2016;145:116–27.

Rowe M, Fitzsimmons L, Bell AI. Epstein-Barr virus and Burkitt lymphoma. Chin J Cancer. 2014;33(12):609–19.

Magrath I. Epidemiology: clues to the pathogenesis of Burkitt lymphoma. Br J Haematol. 2012;156:744–56.

Nicolae A, Pittaluga S, Abdullah S, et al. EBV-positive large B-cell lymphomas in young patients: a nodal lymphoma with evidence for a tolerogenic immune environment. Blood. 2015;126:863–72.

Cohen M, Narbaitz M, Metrebian F, et al. Epstein-Barr virus-positive diffuse large B-cell lymphoma association is not only restricted to elderly patients. Int J Cancer. 2014;135:2816–24.

Acknowledgements

We thank Christopher Lavender for editing the manuscript.

Funding

This study was supported by Sister Institution Network Fund of the University of Texas MD Anderson Cancer Center (to Huilan Rao) and the Medical Scientific Research Foundation of Guangdong Province, China (A2017009).

Availability of data and materials

The datasets generated during and/or analyzed for this study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

HYH and QCF equally contributed to the work. RHL, HYH and QCF designed the study, and QCF drafted the manuscript. FYF and HYH contributed to the diagnoses. LM and GN assisted in patient selection and figure preparation. RHL guided the whole study and revised the manuscript. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

This study was ethically approved by Sun Yat-sen University Cancer Center IRB (Approval No: YB2017-030), and has been granted exemption from requiring informed consent to participate from participants.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Additional file

Additional file 1:

Table S1. Distribution of NHL subtypes in children and adolescents in South China (Ν = 501). (DOCX 19 kb)

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made. The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver (http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/) applies to the data made available in this article, unless otherwise stated.

About this article

Cite this article

Qin, C., Huang, Y., Feng, Y. et al. Clinicopathological features and EBV infection status of lymphoma in children and adolescents in South China: a retrospective study of 662 cases. Diagn Pathol 13, 17 (2018). https://doi.org/10.1186/s13000-018-0693-0

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s13000-018-0693-0