Abstract

Background

Mutations in the TERT promoter, ALK rearrangement, and the BRAF V600E mutation are associated with aggressive clinicopathologic features in thyroid cancers. However, little is known about the impact of TERT promoter mutations and ALK rearrangement in thyroid cancer patients with a high prevalence of BRAF mutations.

Methods

We performed Sanger sequencing to detect BRAF V600E and TERT promoter mutations and both immunohistochemistry and fluorescence in situ hybridization to identify ALK rearrangement on 243 thyroid cancers.

Results

TERT promoter mutations were not present in 192 well-differentiated thyroid carcinomas (WDTC) without distant metastasis or in 9 medullary carcinomas. However, the mutations did occur in 40 % (12/30) of WDTC with distant metastasis, 29 % (2/7) of poorly differentiated carcinomas and 60 % (3/5) of anaplastic carcinomas. ALK rearrangement was not present in all thyroid cancers. The BRAF V600E mutation was more frequently found in WDTC without distant metastasis than in WDTC with distant metastasis (p = 0.007). In the cohort of WDTC with distant metastasis, patients with wild-type BRAF and TERT promoter had a significantly higher response rate after radioiodine therapy (p = 0.024), whereas the BRAF V600E mutation was significantly correlated with progressive disease (p = 0.025).

Conclusions

The TERT promoter mutation is an independent predictor for distant metastasis of WDTC, but ALK testing is not useful for clinical decision-making in Korean patients with a high prevalence of the BRAF V600E mutation. Radioiodine therapy for distant metastasis of WDTC is most effective in patients without BRAF V600E and TERT promoter mutations.

Similar content being viewed by others

Background

Thyroid cancer is the most common type of endocrine tumor, with an incidence that has significantly increased in the last few decades [1, 2]. Although well-differentiated thyroid carcinoma (WDTC) is one of the most curable of all cancers, approximately 10–20 % of patients with WDTC suffer from disease recurrence after surgery, and some eventually die from the disease [3–5]. Various risk stratification methods have been used for the proper management of patients with WDTC; however, none are completely accurate [6].

Molecular biomarkers have been used as an adjunct diagnostic marker of thyroid cancer and a predictor of patient prognosis [7, 8]. The BRAF V600E mutation is the most common mutation in thyroid cancer, particularly in papillary thyroid carcinoma (PTC), and plays an important role in tumorigenesis and progression [9–14]. In Korea, PTC comprises 97.3 % of all thyroid cancers according to new data from the 2014 annual report of cancer statistics in Korea (http://www.cancer.go.kr/). The BRAF V600E mutation is highly prevalent in Korean PTC patients [11]. Currently, there is controversy regarding whether the BRAF V600E mutation is associated with poor prognosis and aggressive clinicopathologic features in Korean PTC patients; therefore, additional prognostic biomarkers to predict a more aggressive disease are needed [9, 15–18].

Somatic mutations of the promoter region of the TERT gene have been reported in various cancers, including thyroid cancers, but are not found in normal cells [19–23]. The frequent cytosine-to-thymine transition of the TERT promoter region occurs at the following positions of chr5: 1 295 228 (C228T) and 1 295 250 (C250T), which correspond to nucleotide changes -124 bp (c.-124C > T) and -146 bp (c.-146C > T) upstream from the ATG start site, respectively (Fig. 1) [19–23]. These TERT promoter mutations stimulate TERT transcriptional activity in cancer cells [19–23]. In thyroid cancers, TERT promoter mutations were predominantly found in more aggressive disease, such as tall cell variant PTC, widely invasive follicular thyroid carcinoma (FTC), poorly differentiated carcinoma, and anaplastic carcinoma [13, 18, 21, 24, 25].

Structure of the wild-type TERT gene and representative sequencing electropherograms of the genomic DNA of the TERT promoter. The g.1295228 C > T (C228T) and g.1295250 C > T (C250T) mutations within the TERT promoter gene result in a cytosine-to thymine transition at 124 bp (c.-124C > T) and 146 bp (c.-146C > T) upstream of the ATG start codon, respectively. g.1295228 C > A (C228A) is a cytosine-to adenine transition at the 1 295 228 position of chr5

ALK gene rearrangements have recently been identified in thyroid cancer [26–30]. EML4, STRN, TFG, and GTF2IRD1 have been reported as ALK fusion partners [27, 28, 30–32]. The prevalence of ALK-rearranged PTCs has been reported to be up to 2.2 %, although the number of study cases is limited [26]. A previous study reported that ALK rearrangements were more frequently found in aggressive thyroid cancer, while another study found mutations only in unselected consecutive PTC cases and not in aggressive disease, such as PTCs with distant metastasis, poorly differentiated carcinomas and anaplastic carcinomas [26, 28].

We aimed to investigate the prevalence of TERT promoter and ALK mutations in thyroid cancer patients with a high prevalence of the BRAF V600E mutation and their potential contribution for the risk stratification of these patients.

Methods

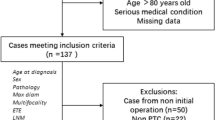

Patients

We retrospectively enrolled 243 patients who underwent thyroid surgery for thyroid cancer at Seoul St. Mary’s Hospital of The Catholic University of Korea with the approval of the Institutional Review Board. Informed consent was obtained from every patient. The thyroid cancers studied included 192 consecutive WDTCs without distant metastasis (consisting of 127 classic PTCs, 11 classic PTCs with tall cell features, 9 encapsulated follicular variant PTCs, 7 infiltrative follicular variant PTCs, 16 tall cell variant PTCs, 1 oncocytic PTC, 1 Warthin-like PTC, and 20 minimally invasive FTCs), 30 consecutive WDTCs with distant metastasis (consisting of 14 classic PTCs, 4 classic PTCs with tall cell features, 1 encapsulated follicular variant PTC, 1 macrofollicular variant PTC, 5 tall cell variant PTCs, 1 columnar cell variant PTC, 1 diffuse sclerosing variant PTC, 2 minimally invasive FTCs, and 1 widely invasive FTC), 7 poorly differentiated carcinomas, 5 anaplastic carcinomas, and 9 medullary carcinomas. PTC was defined as a classic type with tall cell features if it consisted of less than 50 % tall cells and as a tall cell variant if it consisted of 50 % or more tall cells [33].

Mutational analyses for BRAF and TERT promoter mutations

Genomic DNA was isolated from manually dissected 10-μm thick paraffin-embedded tissue sections using the RecoverAll™ Total Nucleic Acid Isolation Kit (Life Technologies, Carlsbad, CA, USA). Sanger sequencing was performed to detect the presence of BRAF V600E and TERT promoter mutations. Exon 15 of the BRAF gene was PCR-amplified as previously reported using the following forward primer (5′-TCATAATGCTTGCTCTGATAGGA-3′) and reverse primer (5′-GGCCAAAAATTTAATCAGTGGA-3′), resulting in a 224 bp PCR product [11, 33, 34]. A 193 bp fragment of the TERT promoter was amplified by PCR as previously reported using the following forward primer (5′-CACCCGTCCTGCCCCTTCACCTT-3′) and reverse primer (5′-GGCTTCCCACGTGCGCAGCAGGA-3′) [35]. All TERT promoter mutations were confirmed using another previously reported primer set that included the following forward primer (5′-AGTGGATTCGCGGGCACAGA-3′) and reverse primer (5′-CAGCGCTGCCTGAAACTC-3′) and resulted in a 235 bp PCR product [21].

Immunohistochemistry for ALK overexpression

Immunohistochemistry was performed on paraffin-embedded whole tissue sections of surgical specimens using the ALK antibody (clone p80, Novocastra Laboratories Ltd., Newcastle upon Tyne, UK) and the Polink-2 HRP plus anti-rabbit DAB detection kit (GBI Labs, Mukilteo, WA, USA). As a positive control, we used paraffin-embedded tissue sections from two lung adenocarcinomas with previously confirmed ALK rearrangement by fluorescence in situ hybridization (FISH).

FISH for ALK rearrangement

We performed FISH to detect ALK rearrangement using a ZytoLight SPEC ALK Dual Color Break Apart Probe and Kit (ZytoVision GmbH, Bremerhaven, Germany) according to the manufacturer’s protocol [29]. The positive criterion for ALK rearrangement was defined as > 15 % of split signal separation and/or isolated red signal in at least 100 tumor cells as previously described [26, 29].

Evaluation of response to radioiodine therapy

All 30 WDTC patients with distant metastasis underwent radioactive iodine (RAI) therapy. The response to RAI ablation was evaluated with a whole body iodine -131 scan, evaluation of serum thyroglobulin levels, and a computerized tomography scan. Clinical outcomes to RAI therapy were classified as complete remission (CR), partial response (PR), stable disease (SD), and progressive disease (PD) according to previously described criteria [36].

Statistical analysis

The Pearson’s chi-square test or Fisher’s exact test was used to assess the relationship between two nominal variables. The Student’s t-test and Mann–Whitney test were used to compare two different groups of continuous parametric or nonparametric data, respectively. For the multivariate analysis, parameters that were significant at p < 0.25 in the univariate analysis were included in a multiple logistic regression test. Two-sided tests with p < 0.05 were considered to be statistically significant. Statistical analysis was performed with SPSS ver. 21.0 software (SPSS Inc., Chicago, IL, USA) and SAS ver. 9.3 software (SAS Institute Inc., Cary, NC, USA).

Meta-analysis of the proportion of TERT promoter mutations

We searched the literature for TERT promoter mutations in thyroid cancer using PubMed and Google up to November 2015, and selected eligible articles. We then conducted a meta-analysis of the proportion of TERT promoter mutations according to the histologic types of thyroid cancers. Cochran Q test and I2 values were employed to assess statistical heterogeneity among studies. If significant heterogeneity was observed (p < 0.10 or I2 > 50 %), the random effect model was used for meta-analysis. Otherwise, we used a fixed-effect model for the meta-analysis. Meta-analyses were performed using done using MedCalc version 13.0.2 software (MedCalc, Ostend, Belgium).

Results

Prevalence of TERT promoter mutations, the BRAF V600E mutation, and ALK rearrangement in thyroid cancers

TERT promoter mutations were found in 12 (40 %) of 30 WDTCs with distant metastasis, 2 (29 %) of 7 poorly differentiated carcinomas, and 3 (60 %) of 5 anaplastic carcinomas. However, no such mutations were present in the 192 WDTCs without distant metastasis or the 9 medullar carcinomas (Table 1). Among TERT promoter mutations, the most common type was C228T (76 %), followed by C250T (18 %) and C250A (6 %) (Table 1) (Fig. 1). Among 12 WDTCs with TERT promoter mutations, the most frequent histologic subtype was the tall cell variant of PTC (Table 1).

The BRAF V600E mutation was found in 142 (83 %) of 172 PTCs without distant metastasis, 15 (56 %) of 27 PTCs with distant metastasis, 1 (14 %) of 7 poorly differentiated carcinomas and 4 (80 %) of 5 anaplastic carcinomas (Table 1). However, the BRAF V600E mutation was not found in 23 FTCs and 9 medullary carcinomas.

None of the 243 thyroid cancers had positive ALK immunohistochemistry or ALK break apart FISH (Table 1).

Relationship between TERT promoter mutations and clinicopathologic features of WDTCs

In 222 patients with WDTC, the presence of TERT promoter mutations was associated with older age (p = 0.017), larger tumor size (p = 0.043), aggressive histologic subtypes (p < 0.001), advanced pathologic T stage (p = 0.014), extrathyroidal extension (p = 0.035), lymph node metastasis (p = 0.011), lateral lymph node metastasis (p < 0.001), distant metastasis (p < 0.001), and advanced AJCC stage (p < 0.001) (Table 2). There was no association between TERT promoter mutations and the BRAF V600E mutation (Table 2).

Relationship between clinicopathologic and molecular features and distant metastases of WDTCs

The mean follow-up period of the patients with WDTC was 36.1 months. In 14 patients, distant metastases were found within 6 months of first diagnosis. Distant metastases occurred in the lung (n = 24), bone (n = 3), lung and bone (n = 2), and brain (n = 1). Distant metastasis was associated with larger tumor size (p = 0.001), aggressive histologic subtype (p = 0.003), advanced pT stage (p < 0.001), extrathyroidal extension (p = 0.001), lymph node metastasis (p < 0.001), lateral lymph node metastasis (p < 0.001) and the TERT promoter mutation (p < 0.001). However, the BRAF V600E mutation was inversely associated with distant metastasis (p = 0.007).

In the multivariate analysis, the odds ratio (OR) for distant metastasis of WDTC in patients harboring tumors with TERT promoter mutations and lateral lymph node metastases was 155.298 (95 % confidence interval (CI) 3.362–999.990) and 11.159 (95 % CI 1.902–65.461), respectively (Table 3). The OR for distant metastases of WDTC in patients harboring tumors with the BRAF V600E mutation was 0.083 (95 % CI 0.021–0.327) (Table 3).

Impact of molecular genotypes on response of metastatic WDTCs to RAI therapy

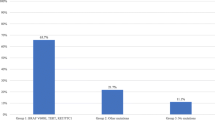

Of the 30 WDTCs with distant metastasis, 9 (30 %) had coexisting BRAF V600E and TERT promoter mutations and 12 (40 %), including follicular and diffuse sclerosing variants of PTC, had no mutations (Fig. 2a).

Molecular genotypes and radioactive iodine therapy. a Molecular genotypes of 30 well-differentiated thyroid carcinomas with distant metastases based on TERT promoter mutations and BRAF V600E. b Structural response of distant metastatic disease to radioactive iodine therapy classified by molecular genotypes in 30 well-differentiated thyroid carcinoma patients with distant metastasis. PTC, papillary thyroid carcinoma; TCF, tall cell features; FTC, follicular thyroid carcinoma; TERT, TERT promoter mutations; BRAF, BRAF V600E; (+), mutation positive; (-), mutation negative

The structural response of distant metastatic disease to RAI was evaluated at least 6 months after RAI therapy. Of the 30 WDTC patients with distant metastasis, six (20 %) patients had PR and six (20 %) had SD after RAI ablation whereas none achieved CR and 18 (60 %) had PD. There was a significant correlation between tumors with the BRAF V600E mutation alone and the progression of distant metastatic disease after RAI therapy (p = 0.025), but TERT promoter mutations alone were not associated with PD (Fig. 2b). PR or SD after RAI therapy was significantly more likely in patients with wild-type BRAF and TERT promoter genes (p = 0.024) (Fig. 2b). However, other combinations of genetic mutations were not correlated with RAI response.

Meta-analysis of TERT promoter mutation prevalence in thyroid cancer

Our study and 13 articles were included for the meta-analysis of TERT promoter mutation prevalence in various thyroid cancers [17, 18, 21, 24, 25, 32, 37–43]. Significant heterogeneity was found in classic PTC, FTC, Hürthle cell carcinoma, and anaplastic carcinoma among the studies (Figs. 3 and 4). The mean frequencies of TERT promoter mutations in PTC, conventional FTC, Hürthle cell carcinoma, poorly differentiated carcinoma and anaplastic carcinoma were 11.3 % (95 % CI 9.3–13.5), 21.3 % (95 % CI 14.2–29.4), 6.7 % (95 % CI 0.2–21.4), 39.6 % (95 % CI 31.3–48.2), and 38.5 % (95 % CI 32.6–44.7), respectively (Figs. 3 and 4). When PTCs were stratified by histologic subtype, mean frequencies of TERT promoter mutations in classic, follicular, and tall cell variants were 8.8 % (95 % CI 6.8–11.1), 6.6 % (95 % CI 4.5–9.3), 27.5 % (95 % CI 21.0–34.7), respectively (Fig. 3). TERT promoter mutations were not found in a total of 132 medullary carcinoma patients including our case series [17, 21, 24, 25, 41].

Discussion

We found that TERT promoter mutations are prevalent in aggressive thyroid cancers and are associated with distant metastasis of WDTCs in Korean patients with a high prevalence of the BRAF V600E mutation. When we examined TERT promoter mutations in a consecutive series of 192 WDTC patients who had no distant metastasis during the follow-up period, none carried the mutation. However, TERT promoter mutations were found in 40 % of WDTC patients with distant metastasis. In all 222 WDTC patients, the overall prevalence of TERT promoter mutations was 5.4 %. These results are lower than those reported in other countries. The prevalence of TERT promoter mutations reported in the literature ranged from 7.3 to 25.5 % in PTC and from 4.3 to 36.4 % in FTC [17, 18, 21, 24, 25, 32, 37–43].

In our study, TERT promoter mutations were associated with older age, larger tumors, higher stage and distant metastases in WDTCs. These findings are consistent with those of previous reports indicating that TERT promoter mutations are associated with aggressive clinical behavior [21, 24]. In the stratified meta-analysis by histologic subtype of PTC, we found that the prevalence of TERT promoter mutations was correlated with the degree of tumor aggressiveness. The tall cell variant of PTC exhibits more aggressive behavior than classic PTC [27, 33], while clinical features of the follicular variant of PTC are between classic PTC and FTC [44]. The TERT promoter mutations were most frequently found in tall cell variant (27.5 %, 95 % CI 21.0–34.7), followed by classic PTC (8.8 %, 95 % CI 6.8–11.1) and follicular variant (6.6 %, 95 % CI 4.5–9.3). These results are consistent with findings of present study.

Many studies have shown the role of BRAF V600E in advanced clinical stage and distant metastasis of PTC [7, 45]. In contrast, we found that the BRAF V600E status was inversely correlated with the rate of distant metastasis in WDTCs. This contradiction may be related to case selection bias. Of 30 metastatic tumors enrolled in our study, 20 % included follicular and diffuse sclerosing variants of PTC and FTCs, which were all negative for the BRAF V600E mutation. It is well-known that the incidence of BRAF V600E is very low in the follicular and diffuse sclerosing variants of PTC, and no FTCs have the BRAF V600E mutation [11, 34, 46].

In our study, the BRAF V600E mutation was significantly associated with low response rate of metastatic WDTCs to RAI therapy. These results are consistent with previous studies that have demonstrated high frequency of BRAFV600E mutation in RAI-refractory metastatic thyroid cancers [1, 47]. However, there was no significant effect of TERT promoter mutations on distant metastasis of WDTCs. The most likely mechanism of resistance to RAI therapy is the impaired iodide-handling machinery in metastatic thyroid cancer [1]. Many studies have reported that BRAFV600E mutation reduces the expression of thyroid iodine-handling genes (sodium iodide symporter, thyroid-stimulating hormone receptor, thyroglobulin, and thyroperoxidase) in thyroid cancer [1, 47, 48]. However, mechanism underlying the RAI therapy resistance associated with TERT promoter mutations remains uncertain. Xing et al reported that coexisting BRAF V600E and TERT C228T mutations defined the most aggressive subgroup of PTC when analyzed in terms of clinicopathologic features, tumor recurrence and disease-free survival rate [18]. We did not observe this trend in our study (data not shown).

Two TERT C228T and C250T mutations create consensus binding motifs for the E-twenty-six (ETS)/ternary complex transcription factor (TCF) and increase the transcriptional activity of the TERT promoter [19, 23]. TERT promoter mutations in thyroid cancer and glioma were associated with increased mRNA expression and telomerase activity [17, 49]. BRAF V600E and TERT promoter mutations can activate the mitogen-activated protein kinase (MAPK) signaling pathway in thyroid cancer [21]. In previous studies, TERT promoter mutations were more frequently found in BRAF V600E mutation-positive PTCs, suggesting an incremental and synergistic effect of the coexisting two mutations in tumorigenesis [18, 21]. In our study, the TERT promoter mutation status was not associated with the incidence of the BRAF V600E mutation. These discrepancies may be associated with ethnic differences given that there is a higher prevalence of the BRAF V600E mutation and lower occurrence of TERT promoter mutations in Korean patients than in Western patients. Therefore, our study results cannot be generalized to other populations.

We found no TERT promoter mutations in medullary carcinoma. This finding is consistent with previous reports [21, 24]. Moreover, TERT promoter mutations were not found in benign thyroid nodules, whereas they were more prevalent in poorly differentiated or anaplastic carcinomas than in WDTCs [21, 24]. Therefore, it is suggested that TERT promoter mutations are involved only in the tumorigenesis of follicular-cell derived thyroid cancers, particularly in aggressive subtypes, and may occur as a late molecular-genetic event that induces dedifferentiation of WDTCs [21].

ALK gene rearrangements are mutually exclusive with all other known thyroid cancer driver mutations and have been reported in up to 2.2 % of PTCs, 4 % of poorly differentiated carcinomas, and 4 % of anaplastic carcinomas [26, 28, 32]. In our study, ALK rearrangement was not identified in any thyroid cancers.

The main limitations of our study were the relatively small sample size of metastatic cancers and the short follow-up period. Although the analyses for disease recurrence and survival of patients were not available, we could evaluate the therapeutic response to RAI based on the distant metastatic disease genotypes. We report for the first time the clinical impact of TERT promoter mutations on thyroid cancers that occur in a BRAF V600E prevalent area.

Conclusions

Our study demonstrated that Korean patients have a higher BRAF V600E prevalence and lower prevalence of the TERT promoter mutation and ALK rearrangement in thyroid cancers than do Western patients. TERT promoter mutation is associated with aggressive clinicopathologic features and is a strong predictor of distant metastasis of WDTC. In Korea, the BRAF V600E-negative WDTCs more frequently develop distant metastasis than BRAF V600E-positive tumors. When WDTC patients develop distant metastases, RAI therapy is most effective in patients without BRAF V600E and TERT promoter mutations. Further prospective evaluation that includes a larger sample size is needed.

Abbreviations

- CI:

-

confidence interval

- CR:

-

complete remission

- FISH:

-

fluorescence in situ hybridization

- FTC:

-

follicular thyroid carcinoma

- MAPK:

-

mitogen-activated protein kinase

- PD:

-

progressive disease

- PR:

-

partial response

- PTC:

-

papillary thyroid carcinoma

- RAI:

-

radioactive iodine

- SD:

-

stable disease

- WDTC:

-

well-differentiated thyroid carcinoma

References

Xing M. Molecular pathogenesis and mechanisms of thyroid cancer. Nat Rev Cancer. 2013;13(3):184–99. doi:10.1038/nrc3431.

Jemal A, Bray F, Center MM, Ferlay J, Ward E, Forman D. Global cancer statistics. CA Cancer J Clin. 2011;61(2):69–90. doi:10.3322/caac.20107.

Toniato A, Boschin I, Casara D, Mazzarotto R, Rubello D, Pelizzo M. Papillary thyroid carcinoma: factors influencing recurrence and survival. Ann Surg Oncol. 2008;15(5):1518–22. doi:10.1245/s10434-008-9859-4.

Mazzaferri EL, Jhiang SM. Long-term impact of initial surgical and medical therapy on papillary and follicular thyroid cancer. Am J Med. 1994;97(5):418–28.

Tuttle RM, Ball DW, Byrd D, Dilawari RA, Doherty GM, Duh QY, et al. Thyroid carcinoma. J Natl Compr Canc Netw. 2010;8(11):1228–74.

Melck AL, Yip L, Carty SE. The utility of BRAF testing in the management of papillary thyroid cancer. Oncologist. 2010;15(12):1285–93. doi:10.1634/theoncologist.2010-0156.

Kim TH, Park YJ, Lim JA, Ahn HY, Lee EK, Lee YJ, et al. The association of the BRAF(V600E) mutation with prognostic factors and poor clinical outcome in papillary thyroid cancer: a meta-analysis. Cancer. 2012;118(7):1764–73. doi:10.1002/cncr.26500.

Xing M, Haugen BR, Schlumberger M. Progress in molecular-based management of differentiated thyroid cancer. Lancet. 2013;381(9871):1058–69. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(13)60109-9.

Kim TY, Kim WB, Song JY, Rhee YS, Gong G, Cho YM, et al. The BRAF mutation is not associated with poor prognostic factors in Korean patients with conventional papillary thyroid microcarcinoma. Clin Endocrinol (Oxf). 2005;63(5):588–93. doi:10.1111/j.1365-2265.2005.02389.x.

Fukushima T, Suzuki S, Mashiko M, Ohtake T, Endo Y, Takebayashi Y, et al. BRAF mutations in papillary carcinomas of the thyroid. Oncogene. 2003;22(41):6455–7. doi:10.1038/sj.onc.1206739.

Cho U, Oh WJ, Bae JS, Lee S, Lee YS, Park GS, et al. Clinicopathological features of rare BRAF mutations in Korean thyroid cancer patients. J Korean Med Sci. 2014;29(8):1054–60. doi:10.3346/jkms.2014.29.8.1054.

Xing M. BRAF mutation in thyroid cancer. Endocr Relat Cancer. 2005;12(2):245–62. doi:10.1677/erc.1.0978.

Xing M, Westra WH, Tufano RP, Cohen Y, Rosenbaum E, Rhoden KJ, et al. BRAF mutation predicts a poorer clinical prognosis for papillary thyroid cancer. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2005;90(12):6373–9. doi:10.1210/jc.2005-0987.

Davies H, Bignell GR, Cox C, Stephens P, Edkins S, Clegg S, et al. Mutations of the BRAF gene in human cancer. Nature. 2002;417(6892):949–54. doi:10.1038/nature00766.

Nam JK, Jung CK, Song BJ, Lim DJ, Chae BJ, Lee NS, et al. Is the BRAF(V600E) mutation useful as a predictor of preoperative risk in papillary thyroid cancer? Am J Surg. 2012;203(4):436–41. doi:10.1016/j.amjsurg.2011.02.013.

Ito Y, Yoshida H, Maruo R, Morita S, Takano T, Hirokawa M, et al. BRAF mutation in papillary thyroid carcinoma in a Japanese population: its lack of correlation with high-risk clinicopathological features and disease-free survival of patients. Endocr J. 2009;56(1):89–97.

Vinagre J, Almeida A, Populo H, Batista R, Lyra J, Pinto V, et al. Frequency of TERT promoter mutations in human cancers. Nat Commun. 2013;4:2185. doi:10.1038/ncomms3185.

Xing M, Liu R, Liu X, Murugan AK, Zhu G, Zeiger MA, et al. BRAF V600E and TERT promoter mutations cooperatively identify the most aggressive papillary thyroid cancer with highest recurrence. J Clin Oncol. 2014;32(25):2718–26. doi:10.1200/JCO.2014.55.5094.

Horn S, Figl A, Rachakonda PS, Fischer C, Sucker A, Gast A, et al. TERT promoter mutations in familial and sporadic melanoma. Science. 2013;339(6122):959–61. doi:10.1126/science.1230062.

Liu X, Wu G, Shan Y, Hartmann C, von Deimling A, Xing M. Highly prevalent TERT promoter mutations in bladder cancer and glioblastoma. Cell Cycle. 2013;12(10):1637–8. doi:10.4161/cc.24662.

Liu X, Bishop J, Shan Y, Pai S, Liu D, Murugan AK, et al. Highly prevalent TERT promoter mutations in aggressive thyroid cancers. Endocr Relat Cancer. 2013;20(4):603–10. doi:10.1530/erc-13-0210.

Killela PJ, Reitman ZJ, Jiao Y, Bettegowda C, Agrawal N, Diaz Jr LA, et al. TERT promoter mutations occur frequently in gliomas and a subset of tumors derived from cells with low rates of self-renewal. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2013;110(15):6021–6. doi:10.1073/pnas.1303607110.

Huang FW, Hodis E, Xu MJ, Kryukov GV, Chin L, Garraway LA. Highly recurrent TERT promoter mutations in human melanoma. Science. 2013;339(6122):957–9. doi:10.1126/science.1229259.

Melo M, da Rocha AG, Vinagre J, Batista R, Peixoto J, Tavares C, et al. TERT promoter mutations are a major indicator of poor outcome in differentiated thyroid carcinomas. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2014;99(5):E754–65. doi:10.1210/jc.2013-3734.

Liu T, Wang N, Cao J, Sofiadis A, Dinets A, Zedenius J, et al. The age- and shorter telomere-dependent TERT promoter mutation in follicular thyroid cell-derived carcinomas. Oncogene. 2014;33(42):4978–84. doi:10.1038/onc.2013.446.

Chou A, Fraser S, Toon CW, Clarkson A, Sioson L, Farzin M, et al. A detailed clinicopathologic study of ALK-translocated papillary thyroid carcinoma. Am J Surg Pathol. 2015;39(5):652–9. doi:10.1097/pas.0000000000000368.

Demeure MJ, Aziz M, Rosenberg R, Gurley SD, Bussey KJ, Carpten JD. Whole-genome sequencing of an aggressive BRAF wild-type papillary thyroid cancer identified EML4-ALK translocation as a therapeutic target. World J Surg. 2014;38(6):1296–305. doi:10.1007/s00268-014-2485-3.

Kelly LM, Barila G, Liu P, Evdokimova VN, Trivedi S, Panebianco F, et al. Identification of the transforming STRN-ALK fusion as a potential therapeutic target in the aggressive forms of thyroid cancer. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2014;111(11):4233–8. doi:10.1073/pnas.1321937111.

Park G, Kim TH, Lee HO, Lim JA, Won JK, Min HS, et al. Standard immunohistochemistry efficiently screens for anaplastic lymphoma kinase rearrangements in differentiated thyroid cancer. Endocr Relat Cancer. 2015;22(1):55–63. doi:10.1530/erc-14-0467.

Perot G, Soubeyran I, Ribeiro A, Bonhomme B, Savagner F, Boutet-Bouzamondo N, et al. Identification of a recurrent STRN/ALK fusion in thyroid carcinomas. PLoS One. 2014;9(1):e87170. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0087170.

McFadden DG, Dias-Santagata D, Sadow PM, Lynch KD, Lubitz C, Donovan SE, et al. Identification of oncogenic mutations and gene fusions in the follicular variant of papillary thyroid carcinoma. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2014;99(11):E2457–62. doi:10.1210/jc.2014-2611.

Network TCGAR. Integrated genomic characterization of papillary thyroid carcinoma. Cell. 2014;159(3):676–90. doi:10.1016/j.cell.2014.09.050.

Oh WJ, Lee YS, Cho U, Bae JS, Lee S, Kim MH, et al. Classic papillary thyroid carcinoma with tall cell features and tall cell variant have similar clinicopathologic features. Korean J Pathol. 2014;48(3):201–8. doi:10.4132/KoreanJPathol.2014.48.3.201.

Jung CK, Im SY, Kang YJ, Lee H, Jung ES, Kang CS, et al. Mutational patterns and novel mutations of the BRAF gene in a large cohort of Korean patients with papillary thyroid carcinoma. Thyroid. 2012;22(8):791–7. doi:10.1089/thy.2011.0123.

Liu T, Brown TC, Juhlin CC, Andreasson A, Wang N, Backdahl M, et al. The activating TERT promoter mutation C228T is recurrent in subsets of adrenal tumors. Endocr Relat Cancer. 2014;21(3):427–34. doi:10.1530/erc-14-0016.

Sabra MM, Dominguez JM, Grewal RK, Larson SM, Ghossein RA, Tuttle RM, et al. Clinical outcomes and molecular profile of differentiated thyroid cancers with radioiodine-avid distant metastases. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2013;98(5):E829–36. doi:10.1210/jc.2012-3933.

Landa I, Ganly I, Chan TA, Mitsutake N, Matsuse M, Ibrahimpasic T, et al. Frequent somatic TERT promoter mutations in thyroid cancer: higher prevalence in advanced forms of the disease. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2013;98(9):E1562–6. doi:10.1210/jc.2013-2383.

Liu X, Qu S, Liu R, Sheng C, Shi X, Zhu G, et al. TERT promoter mutations and their association with BRAF V600E mutation and aggressive clinicopathological characteristics of thyroid cancer. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2014;99(6):E1130–6. doi:10.1210/jc.2013-4048.

Dettmer MS, Schmitt A, Steinert H, Capper D, Moch H, Komminoth P, et al. Tall cell papillary thyroid carcinoma: new diagnostic criteria and mutations in BRAF and TERT. Endocr Relat Cancer. 2015;22(3):419–29. doi:10.1530/erc-15-0057.

Gandolfi G, Ragazzi M, Frasoldati A, Piana S, Ciarrocchi A, Sancisi V. TERT promoter mutations are associated with distant metastases in papillary thyroid carcinoma. Eur J Endocrinol. 2015;172(4):403–13. doi:10.1530/eje-14-0837.

Muzza M, Colombo C, Rossi S, Tosi D, Cirello V, Perrino M, et al. Telomerase in differentiated thyroid cancer: promoter mutations, expression and localization. Mol Cell Endocrinol. 2015;399:288–95. doi:10.1016/j.mce.2014.10.019.

Qasem E, Murugan AK, Al-Hindi H, Xing M, Almohanna M, Alswailem M, et al. TERT promoter mutations in thyroid cancer: a report from a Middle Eastern population. Endocr Relat Cancer. 2015;22(6):901–8. doi:10.1530/erc-15-0396.

Shi X, Liu R, Qu S, Zhu G, Bishop J, Liu X, et al. Association of TERT promoter mutation 1,295,228 C > T with BRAF V600E mutation, older patient age, and distant metastasis in anaplastic thyroid cancer. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2015;100(4):E632–7. doi:10.1210/jc.2014-3606.

Yu XM, Schneider DF, Leverson G, Chen H, Sippel RS. Follicular variant of papillary thyroid carcinoma is a unique clinical entity: a population-based study of 10,740 cases. Thyroid. 2013;23(10):1263–8. doi:10.1089/thy.2012.0453.

Hong AR, Lim JA, Kim TH, Choi HS, Yoo WS, Min HS, et al. The frequency and clinical implications of the BRAF(V600E) mutation in papillary thyroid cancer patients in Korea over the past two decades. Endocrinol Metab (Seoul). 2014;29(4):505–13. doi:10.3803/EnM.2014.29.4.505.

Pillai S, Gopalan V, Smith RA, Lam AK. Diffuse sclerosing variant of papillary thyroid carcinoma--an update of its clinicopathological features and molecular biology. Crit Rev Oncol Hematol. 2015;94(1):64–73. doi:10.1016/j.critrevonc.2014.12.001.

Zhang Z, Liu D, Murugan AK, Liu Z, Xing M. Histone deacetylation of NIS promoter underlies BRAF V600E-promoted NIS silencing in thyroid cancer. Endocr Relat Cancer. 2014;21(2):161–73. doi:10.1530/erc-13-0399.

Yang K, Wang H, Liang Z, Liang J, Li F, Lin Y. BRAFV600E mutation associated with non-radioiodine-avid status in distant metastatic papillary thyroid carcinoma. Clin Nucl Med. 2014;39(8):675–9. doi:10.1097/rlu.0000000000000498.

Huang DS, Wang Z, He XJ, Diplas BH, Yang R, Killela PJ, et al. Recurrent TERT promoter mutations identified in a large-scale study of multiple tumour types are associated with increased TERT expression and telomerase activation. Eur J Cancer. 2015;51(8):969–76. doi:10.1016/j.ejca.2015.03.010.

Acknowledgement

This research was supported by Basic Science Research Program through the National Research Foundation of Korea (NRF) funded by the Ministry of Science, ICT and future planning (2013R1A2A2A01068570).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Authors’ contributions

JB and CJ participated in the design of the study and drafted the manuscript. JB, YK, SJ, SK, SL, MK, DL and YL collected patient material and revised the manuscript critically for important intellectual content. YK, SJ, SK, TK, YL and CJ performed the experiments. JB, TK, SL, MK, DL, YL and CJ participated in data analysis. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made. The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver (http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/) applies to the data made available in this article, unless otherwise stated.

About this article

Cite this article

Bae, J.S., Kim, Y., Jeon, S. et al. Clinical utility of TERT promoter mutations and ALK rearrangement in thyroid cancer patients with a high prevalence of the BRAF V600E mutation. Diagn Pathol 11, 21 (2016). https://doi.org/10.1186/s13000-016-0458-6

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s13000-016-0458-6