Abstract

Study design

Single-centre, two-parallel group, methodological randomised controlled trial to assess blinding feasibility.

Background

Trials of manual therapy interventions of the back face methodological challenges regarding blinding feasibility and success. We assessed the feasibility of blinding an active manual soft tissue mobilisation and control intervention of the back. We also assessed whether blinding is feasible among outcome assessors and explored factors influencing perceptions about intervention assignment.

Methods

On 7–8 November 2022, 24 participants were randomly allocated (1:1 ratio) to active or control manual interventions of the back. The active group (n = 11) received soft tissue mobilisation of the lumbar spine. The control group (n = 13) received light touch over the thoracic region with deep breathing exercises. The primary outcome was blinding of participants immediately after a one-time intervention session, as measured by the Bang blinding index (Bang BI). Bang BI ranges from –1 (complete opposite perceptions of intervention received) to 1 (complete correct perceptions), with 0 indicating ‘random guessing’—balanced ‘active’ and ‘control’ perceptions within an intervention arm. Secondary outcomes included blinding of outcome assessors and factors influencing perceptions about intervention assignment among both participants and outcome assessors, explored via thematic analysis.

Results

24 participants were analysed following an intention-to-treat approach. 55% of participants in the active manual soft tissue mobilisation group correctly perceived their group assignment beyond chance immediately after intervention (Bang BI: 0.55 [95% confidence interval (CI), 0.25 to 0.84]), and 8% did so in the control group (0.08 [95% CI, −0.37 to 0.53]). Bang BIs in outcome assessors were 0.09 (−0.12 to 0.30) and −0.10 (−0.29 to 0.08) for active and control participants, respectively. Participants and outcome assessors reported varying factors related to their perceptions about intervention assignment.

Conclusions

Blinding of participants allocated to an active soft tissue mobilisation of the back was not feasible in this methodological trial, whereas blinding of participants allocated to the control intervention and outcome assessors was adequate. Findings are limited due to imprecision and suboptimal generalisability to clinical settings. Careful thinking and consideration of blinding in manual therapy trials is warranted and needed.

Trial registration

ClinicalTrials.gov: NCT05822947 (retrospectively registered)

Similar content being viewed by others

Background

Manual therapy (MT) remains a guideline-compliant therapeutic option for back pain [1]. Yet, maintaining methodological quality in randomised controlled trials (RCTs) of MT interventions of the back poses challenges, particularly with respect to: (a) the design of a control (’sham‘) intervention and (b) the blinding status of participants and outcome assessors [2,3,4]. These challenges—compounded by poor reporting and contested blinding reporting standards [5]—can compromise internal validity via performance and detection biases [3]. Optimal implementation of high-quality MT trials requires assessing the feasibility of blinding participants and outcome assessors. Methodological trials focused on the assessment of blinding remain an opportunity for advancement in the field of MT RCTs [6,7,8].

The following methodological trial was conducted within the setting of a practice-based doctoral-level epidemiology course at the University of Zurich, Switzerland. Practice-based teaching methods are gaining traction in epidemiology curricula to foster skills among junior researchers in academic settings [9], including the development of scientific questions, and the planning, conduct, and analysis of RCTs. A multidisciplinary group of junior researchers was formed and challenged to design and execute a methodological RCT of MT interventions in a ‘learning-by-doing’ assignment—from research question formulation to final report and presentation of findings.

The primary objective of this methodological trial was to assess the feasibility of blinding an active manual soft tissue mobilisation and a control intervention of the back after a one-time intervention session. The secondary objective was to assess the feasibility of blinding the above interventions among outcome assessors and explore factors influencing perceptions about intervention assignment among participants and outcome assessors.

Methods

Study design and participants

The trial protocol along with the statistical analysis plan are available in Supplementary Material 1. This study was a two-parallel arm (allocation ratio 1:1), single-centre methodological RCT conducted among graduate students to assess the feasibility of blinding an active manual soft tissue mobilisation and a control intervention of the back. No changes were made to the methods after the launch of the trial. This manuscript was prepared in accordance with the 2010 Consolidated Standards of Reporting Trials (CONSORT) checklist extension for pilot and feasibility trials (Supplementary Material 2) [10].

This RCT included adults aged 18 years or older, enrolled in a practice-based doctoral-level epidemiology course at the University of Zurich (UZH), Switzerland. Research Electronic Data Capture (REDCap 12.5.14) was used to collect and store trial data.

Individuals were excluded if they reported pregnancy, had a serious pathology (i.e., cancer, severe scoliosis, inflammatory disease, infection, cauda equina syndrome or progressive motor deficit ≤ M3), a history of spine surgery, or an obvious contraindication to MT of the back (i.e., spinal fracture).

The independent research ethics committee of Canton Zurich (Kantonale Ethikkommission Zürich) deemed that approval was not required for this methodological trial of graduate students pursuant to Art. 2 (outside scope) of the Swiss Federal Act on Research involving Human Beings (Human Research Act, HRA). All participants provided electronic informed consent.

Randomisation and blinding

Randomisation was computer-generated using permuted blocks of sizes two and four and stratified by ‘previous experience with MT’—operationalised as lifetime experience either providing MT as a healthcare professional or receiving MT in a healthcare setting. The allocation list was created by an independent biostatistician [11], and concealed within REDCap [12].

Study participants remained blinded to the primary trial objective, as the study information and consent form (Supplementary Material 3) masked the blinding assessment study aim. The study information form stated that the study aimed ‘to evaluate the effect of a MT intervention on back function by juxtaposing an active and control intervention’.

By nature of the intervention, intervention providers could not be blinded to intervention assignment, but were kept in a separate room. Intervention providers did not disclose the assigned intervention to participants or trial team members and performed randomisation immediately before intervention delivery. Outcome assessors, as well as data analysts remained blinded to the assigned intervention until analyses had been completed.

Intervention procedures

Active manual soft tissue mobilisation and control interventions were designed to resemble each other in terms of participant-intervention provider interaction and duration (3 to 4 min). The active intervention involved a one-time session of mobilisation of the lumbar paraspinal musculature. With participants lying prone on a chiropractic table, the intervention provider applied hand-reinforced circumferential movements to six focal areas, using continuous ischemic compression strokes, and adjusting the pressure to participants’ tolerability (Supplementary Material 4, Figure S1). The active intervention was intentionally not designed to reflect a real-world clinical intervention by protocol. Yet, it contained an active element—a mechanical stimulus delivered to specific soft tissues with sufficient force and therapeutic intent [13]. The hypothesised mechanism of action at the soft tissue level was a decrease in muscle tone and stiffness leading to a potential increase in range of motion [13].

The control intervention included a one-time session of light touch to six distal, broad areas of the thoracic region, with a synchronised breathing exercise (Supplementary Material 4, Figure S1). The control intervention was not previously validated, although light touch in alternate areas is a common protocol in sham-controlled MT trials [3].

Both interventions were delivered by two members of the trial team after being trained in the intervention protocols by the corresponding author (JML, a Doctor of Chiropractic). Intervention providers were trained to standardise verbal and non-verbal cues (contextual effects) and followed a script for consistent interactions with participants.

Range of motion assessment procedures

Three outcome assessors—Assessors 1, 2, and 3—were trained to measure range of motion (ROM) immediately before and after the one-time intervention session. ROM was measured standing by placing a mobile phone device at T12 using the iOS application Measure® (iOS version 16.0.2, iPhone® model X, Apple Inc., California), a suggested valid and reliable method [14,15,16]. Assessors 1 and 2 (‘measuring outcome assessors’) identified T12 through palpation and held the ROM measuring device in place as participants completed movements. Measuring outcome assessors were visually shielded from the measurement reading. Assessor 3 (‘documenting outcome assessor’) recorded measurement readings and was the only outcome assessor to actually see the ROM measurement values. A summary of the prespecified Standard Operating Procedures of the trial can be found in Supplementary Material 5.

Outcomes

The prespecified primary outcome was blinding among participants immediately after a one-time intervention session, as measured by the Bang blinding index (see Table S1 in Supplementary Material 6 for relevant equations for Bang BI point estimate and variance) [17]. Data for the primary outcome were collected at the end of the post-intervention questionnaire, by asking participants: ‘To what extent do you know which intervention (active intervention or control intervention) you received?’. Possible responses were: ‘I strongly believe that I received the active intervention’, ‘I somewhat believe that I received the active intervention’, ‘I somewhat believe that I received the control intervention’, ‘I strongly believe that I received the control intervention’, and ‘I do not know’. The Bang BI ranges from –1 (complete opposite perception of intervention received) to 1 (complete correct perception of intervention received), with 0 indicating ‘random guessing’—balanced perceptions of ‘active’ and ‘control’ intervention received within an intervention arm. It can be interpreted as the proportion of participants who correctly perceived their intervention assignment within an intervention arm beyond chance. ‘Adequate blinding’ was operationalised as a Bang BI between –0.2 and 0.2 [18].

The arm-specific Bang BI point estimates and variances can be summed (BIactive + BIcontrol) to measure the between-arm difference in proportions of the same intervention perception—obtaining a measure of study-level blinding. A summed Bang BI of 0 is desirable and generally implies an equal proportion of participants in both arms perceiving they received active intervention [19]. Values between –0.3 and 0.3 may suggest ‘adequate blinding’ (personal communication with Prof. Heejung Bang, 2 February 2023), although summed Bang BIs vary across interventions [19].

The first secondary outcome was blinding of participants, measured by the James BI [20]—an alternative measure of study-level blinding [7]—and calculated from the same data as the primary outcome. The James BI ranges from 0 (complete correct perceptions of intervention received) to 1 (complete ‘do not know’ perceptions), where 0.5 corresponds to 50% of perceptions being correct, and 50% incorrect. Lack of ‘adequate blinding’ is suggested when the upper bound of the two-sided confidence interval of the James BI is less than 0.5.

The next secondary outcome was blinding of outcome assessors immediately after the one-time intervention session following the Bang approach [17]. Data were collected by asking outcome assessors: ‘To what extent do you know which intervention (active intervention or control intervention) the participant received?’. Possible responses were: ‘I strongly believe that they received the active intervention’, ‘I somewhat believe that they received the active intervention’, ‘I somewhat believe that they received the control intervention’, ‘I strongly believe that they received the control intervention’, and ‘I do not know’.

Factors contributing to perceived intervention arm assignment among study participants and outcome assessors were explored with an open-ended question. Other outcomes were added to keep participants unaware of the blinding assessment trial objective. These included back function, operationalised as four items about ‘ache, pain, or discomfort’ (Cornell Musculoskeletal Discomfort Questionnaire), and self-reported back flexibility (International Fitness Scale) [21, 22]. Additionally, we incorporated a measure of maximum ROM in flexion and extension of the back.

Statistical analysis

Given that the maximum sample size was fixed at the total number of students enrolled in the course (n = 26), a precision-based approach was used to consider sample size (i.e., width of the 95% confidence interval [CI]) for the arm-specific Bang BI estimates [23]. For a sample size of 26 participants, the 95% CI was the observed BI point estimate ± 0.315 points (0.63 points width of the 95% CI) for the group-specific Bang BI, according to Thompson’s method (Eq. 1) as described by Landsman and colleagues [24].

A concise statistical analysis plan was specified and developed a priori (Supplementary Material 1, section 10). To address the primary objective of the trial, blinding was analysed following an intention-to-treat approach. Descriptive statistics (medians and interquartile ranges for quantitative data and counts and percentages for categorical data) were calculated for all primary and secondary outcomes. No formal statistical tests of between-group differences were performed for back function or ROM outcomes, as this did not align with our primary objective. Factors contributing to perceptions about intervention arm assignment among study participants, as well as outcome assessors, were qualitatively analysed using an inductive approach. Following a pragmatic thematic analysis, three trial team members with experience in qualitative methods independently collated the responses and subsequently grouped them thematically by consensus [25]. All analyses were conducted using R [26], with use of the R package BI version 1.1.0 [27] to calculate BIs—both Bang and James.

Results

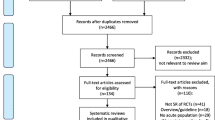

26 students were approached and assessed for eligibility on November 7, 2022. 24 participants (active manual soft tissue mobilisation [n = 11]: median age [IQR], 28 [27 to 30] years, 64% women; control [n = 13]: median age [IQR], 28 [28 to 32] years, 77% female) were enrolled, randomised, and received their allocated intervention on November 8, 2022. There were no losses or exclusions after randomisation (Fig. 1). There were no missing data in the primary outcome. Both groups were comparable in most baseline characteristics (Table 1). Compared to the active manual soft tissue mobilisation, the control group had one more participant with MT experience and three more participants with self-reported ‘good or very good’ back flexibility (Table 1). Participants spent a median of 3.5 min (IQR, 3.2 to 4.1 min) receiving interventions and a median of 10.2 min (IQR, 9.9 to 10.3) for all trial procedures.

Blinding

Blinding of participants

Participant perceptions about intervention arm assignment, resulted in a Bang BI of 0.55 (95% CI, 0.25 to 0.84) in the active manual soft tissue mobilisation arm, and 0.08 (95% CI, -0.37 to 0.53) in the control arm (Table 2). These indices suggested that 55% of the active manual soft tissue mobilisation group correctly perceived their assigned intervention beyond chance, compared to 8% in the control group. Hence, the summed Bang BI was 0.63 (0.09 to 1.17). The James BI yielded an estimate of 0.53 (95% CI, 0.35 to 0.72). Full results of the blinding assessment in participants are provided in Supplementary Material 7, Table S2. Table S3 presents full results by levels of MT experience.

Blinding of outcome assessors

Bang BIs in outcome assessors were 0.09 (-0.12 to 0.30) and –0.10 (-0.29 to 0.08) for perceived assignment of active and control participants, respectively. The summed Bang BI for outcome assessors was –0.01 (-0.29 to 0.27). At the individual outcome assessor level, Bang BI estimates varied. Assessor 1 marked all responses as ‘I do not know’—this prevented any Bang BI calculation (mathematically undefinable). However, the interpretation of James BI for this assessor is compatible with optimal blinding (complete ambivalence). Assessor 2 had Bang BI estimates of 0.27 (95% CI, -0.09 to 0.64) and –0.23 (95% CI, -0.54 to 0.08) for the active and control arms, respectively. Assessor 3 had Bang BI estimates of 0.00 (95% CI, -0.50 to 0.50) and –0.08 (95% CI, -0.53 to 0.37). Table 2 presents BI estimates for outcome assessors. Full results of the blinding assessment in outcome assessors are provided in Supplementary Material 7, Table S4.

Range of motion, back discomfort, and self-perceived flexibility

There were no between-group differences in any of the ROM outcomes (Table 2). Changes in back discomfort and self-perceived flexibility were comparable by levels of actual and perceived intervention assignment (Supplementary Material 7, Table S5).

Factors contributing to perceived intervention assignment

Participants reported uncertainty regarding their perceived intervention assignment. Some mentioned that the applied manual pressure during the intervention as well as a perceived immediate intervention effect informed their justification of perceived intervention arm assignment. Other influencing factors included the use of breathing and contextual elements, such as the atmosphere during intervention delivery (Table 3).

Assessors 1 and 2 lacked certainty to justify their perceptions of intervention assignment among participants. In some instances, these assessors rationalised their choice based on participants’ verbal cues, speed or ease of movement, and perceived ROM. Assessor 3 justified most responses based on recorded ROM measurement readings.

Adverse events

There was one mild adverse event reported in the control group immediately after the intervention—a transient exacerbation of an existing left subscapular complaint, which was deemed unrelated to the intervention.

Discussion

Major findings

In the present methodological trial, we assessed the feasibility of blinding an active manual soft tissue mobilisation and a control intervention of the back. We found that 55% of participants allocated to the active soft tissue intervention correctly identified their intervention assignment beyond chance level—suggesting that blinding in this group was not feasible. Our findings suggest that blinding of participants allocated to the control intervention and outcome assessors was adequate in our study.

The reported factors contributing to perceptions of the assigned intervention indicate that various aspects may influence blinding, including immediate intervention effects and manual pressure. These factors may vary based on trial roles.

Comparison with existing evidence

Our Bang BI estimates for participants were similar to those of a recent meta-analysis of back pain RCTs [19]. Sham-controlled trials of MT for the back [28,29,30,31] have varied in their design of control interventions, including a range of light touch, drop table, and detuned instruments. Recent studies have also varied in their timing and blinding assessment methods, with a recent high-quality trial of MT [32] using the credibility/expectancy questionnaire [33].

Ethical considerations

Methodological trials of blinding feasibility face ethical challenges with respect to the design of study information forms. In our study, the blinding assessment objective was not disclosed to participants until the end of the trial, which could have been considered a minor form of deception by some. However, by masking the study objective, the risk for positive or social desirability bias was mitigated [34]. Since the two interventions entailed minimal risks and full disclosure was provided at trial closure, we believe that according to Article 18 of the Swiss Human Research Act [35], the trial procedures were unlikely to be classified as involving incomplete study information. In addition, the research ethics committee of Canton Zurich deemed that approval was not required for this methodological trial pursuant to Art. 2 (outside scope) of the Swiss Federal Act on Research involving Human Beings (Human Research Act, HRA).

Strengths and limitations

Our study has strengths. First, our RCT design maximised comparability between groups at baseline. Second, we maintained high quality during trial implementation and execution by concealing the allocation sequence, having no deviations from our prespecified protocol, benefitting from no missing data in our primary outcome, choosing a validated and following a standardised method for outcome measurement, analysing our trial results in accordance with our prespecified statistical analysis plan, and reporting on all of our prespecified outcomes [36]. Third, our assessment of blinding extended beyond participants and included outcome assessors, who are often neglected in blinding assessments. Fourth, to our knowledge, this is the first study to include a qualitative exploration of factors influencing perceptions about intervention assignment—an approach that can help to inform the design and procedures of future MT trials.

Our study has limitations. First, we were restricted to a small sample of doctoral students, which limited the precision and generalisability of our BI estimates. Second, our methodological trial was conducted in a non-clinical setting and interventions were delivered by persons with minimal MT training. Future blinding feasibility trials of MT should expand this preliminary work in clinical populations and settings [37]. Third, by conducting a single intervention session and assessing blinding at one time point, we were unable to evaluate possible temporal effects on blinding. Despite their potential added value, longitudinal assessments of blinding may be prone to evolving ‘hunches’ (i.e., perceptions about intervention assignment influenced by multiple treatment sessions and effects) [6, 38]. Fourth, our control intervention was not validated and the possibility that it contained active therapeutic components cannot be ruled out. The appropriateness of our control intervention may have been influenced by our beliefs about what constituted the active element of the manual soft tissue mobilisation intervention [39]. Fifth, our blinding assessment was restricted to the evaluation of perceptions about intervention assignment and did not capture other recommended constructs (e.g., credibility or expectancy [33]) relevant in sham-controlled trials [40].

Conclusion

Blinding of participants allocated to an active soft tissue mobilisation of the back was not feasible in this methodological trial. However, blinding of participants allocated to the control intervention and outcome assessors was adequate. Factors contributing to perceptions about intervention assignment provide valuable information for future trial methods and blinding approaches. Careful consideration and assessment of blinding in MT trials is warranted and needed.

Data availability

The collected data files and other materials are available on reasonable request from the corresponding author.

Abbreviations

- BI:

-

Blinding index

- MT:

-

Manual therapy

- ROM:

-

Range of motion

- UZH:

-

University of Zurich

References

Qaseem A, Wilt TJ, McLean RM, Forciea MA. Noninvasive treatments for acute, subacute, and chronic low back pain: a clinical practice guideline from the American College of Physicians. Ann Intern Med. 2017;166:514–30.

Rubinstein SM, Zoete A, van de, Middelkoop M, Assendelft WJJ, de Boer MR, van Tulder MW. Benefits and harms of spinal manipulative therapy for the treatment of chronic low back pain: systematic review and meta-analysis of randomised controlled trials. BMJ. 2019;364:l689.

Puhl AA, Reinhart CJ, Doan JB, Vernon H. The quality of placebos used in randomized, controlled trials of lumbar and pelvic joint thrust manipulation—a systematic review. Spine J. 2017;17:445–56.

Lavazza C, Galli M, Abenavoli A, Maggiani A. Sham treatment effects in manual therapy trials on back pain patients: a systematic review and pairwise meta-analysis. BMJ Open. 2021;11:e045106.

Nejstgaard CH, Boutron I, Chan A-W, Chow R, Hopewell S, Masalkhi M et al. A scoping review identifies multiple comments suggesting modifications to SPIRIT 2013 and CONSORT 2010. J Clin Epidemiol. 2023;S0895435623000033.

Sackett DL. Turning a blind eye: why we don’t test for blindness at the end of our trials. BMJ. 2004;328:1136.

Bang H, Flaherty SP, Kolahi J, Park J. Blinding assessment in clinical trials: a review of statistical methods and a proposal of blinding assessment protocol. Clin Res Regul Aff. 2010;27:42–51.

Hohenschurz-Schmidt D, Draper-Rodi J, Vase L, Scott W, McGregor A, Soliman N, et al. Blinding and sham control methods in trials of physical, psychological, and self-management interventions for pain (article II): a meta-analysis relating methods to trial results. Pain. 2023;164:509–33.

Abraham A, Gille D, Puhan MA, ter Riet G, von Wyl V, for the International Consortium on Teaching Epidemiology. Defining core competencies for epidemiologists in academic settings to tackle tomorrow’s health research challenges: a structured, multinational effort. Am J Epidemiol. 2021;190:343–52.

Eldridge SM, Chan CL, Campbell MJ, Bond CM, Hopewell S, Thabane L, et al. CONSORT 2010 statement: extension to randomised pilot and feasibility trials. BMJ. 2016;355:i5239.

Snow G. blockrand: randomization for block random clinical trials [Internet]. 2013. Available from: https://CRAN.R-project.org/package=blockran.

Harris PA, Taylor R, Thielke R, Payne J, Gonzalez N, Conde JG. Research electronic data capture (REDCap)—a metadata-driven methodology and workflow process for providing translational research informatics support. J Biomed Inform. 2009;42:377–81.

Bialosky JE, Beneciuk JM, Bishop MD, Coronado RA, Penza CW, Simon CB, et al. Unraveling the mechanisms of manual therapy: modeling an approach. J Orthop Sports Phys Ther. 2018;48:8–18.

de Brito Macedo L, Borges DT, Melo SA, da Costa KSA, de Oliveira Sousa C, Brasileiro JS. Reliability and concurrent validity of a mobile application to measure thoracolumbar range of motion in low back pain patients. J Back Musculoskelet Rehabil. 2020;33:145–51.

Pourahmadi MR, Taghipour M, Jannati E, Mohseni-Bandpei MA, Ebrahimi Takamjani I, Rajabzadeh F. Reliability and validity of an iPhone(®) application for the measurement of lumbar spine flexion and extension range of motion. PeerJ. 2016;4:e2355.

Kolber MJ, Pizzini M, Robinson A, Yanez D, Hanney WJ. The reliability and concurrent validity of measurements used to quantify lumbar spine mobility: an analysis of an iphone® application and gravity based inclinometry. Int J Sports Phys Ther. 2013;8:129–37.

Bang H, Ni L, Davis CE. Assessment of blinding in clinical trials. Control Clin Trials. 2004;25:143–56.

Moroz A, Freed B, Tiedemann L, Bang H, Howell M, Park JJ. Blinding measured: a systematic review of randomized controlled trials of acupuncture. Evid-Based Complement Altern Med ECAM. 2013;2013:708251.

Freed B, Williams B, Situ X, Landsman V, Kim J, Moroz A, et al. Blinding, sham and treatment effects in randomized controlled trials for back pain in 2000–2019: a review and meta-analytic approach. Clin Trials. 2021;18:361–70.

James KE, Bloch DA, Lee KK, Kraemer HC, Fuller RK. An index for assessing blindness in a multi-centre clinical trial: disulfiram for alcohol cessation — a VA cooperative study. Stat Med. 1996;15:1421–34.

Hedge A, Morimoto S, Mccrobie D. Effects of keyboard tray geometry on upper body posture and comfort. Ergonomics. 1999;42:1333–49.

Ortega FB, Ruiz JR, España-Romero V, Vicente-Rodriguez G, Martínez-Gómez D, Manios Y, et al. The International Fitness Scale (IFIS): usefulness of self-reported fitness in youth. Int J Epidemiol. 2011;40:701–11.

Bland JM. The tyranny of power: is there a better way to calculate sample size? BMJ. 2009;339:b3985.

Landsman V, Fillery M, Vernon H, Bang H. Sample size calculations for blinding assessment. J Biopharm Stat. 2018;28:857–69.

Braun V, Clarke V. Using thematic analysis in psychology. Qual Res Psychol. 2006;3:77–101.

R Core Team. R: a language and environment for statistical computing. Vienna, Austria: R Foundation for Statistical Computing; Available from: https://www.R-project.org/.

Schwartz M, Mercaldo N. BI: blinding assessment indexes for randomized, controlled, clinical trials [Internet]. 2022. Available from: https://CRAN.R-project.org/package=BI.

Hoiriis KT, Pfleger B, McDuffie FC, Cotsonis G, Elsangak O, Hinson R, et al. A randomized clinical trial comparing chiropractic adjustments to muscle relaxants for subacute low back pain. J Manipulative Physiol Ther. 2004;27:388–98.

Hawk C, Long CR, Rowell RM, Gudavalli MR, Jedlicka J. A randomized trial investigating a chiropractic manual placebo: a novel design using standardized forces in the delivery of active and control treatments. J Altern Complement Med N Y N. 2005;11:109–17.

Bialosky JE, George SZ, Horn ME, Price DD, Staud R, Robinson ME. Spinal manipulative therapy-specific changes in pain sensitivity in individuals with low back pain. J Pain. 2014;15:136–48.

Walker BF, Hebert JJ, Stomski NJ, Losco B, French SD. Short-term usual chiropractic care for spinal pain: a randomized controlled trial. Spine. 2013;38:2071–8.

Nguyen C, Boutron I, Zegarra-Parodi R, Baron G, Alami S, Sanchez K, et al. Effect of osteopathic manipulative treatment vs sham treatment on activity limitations in patients with nonspecific subacute and chronic low back pain: a randomized clinical trial. JAMA Intern Med. 2021;181:620–30.

Devilly GJ, Borkovec TD. Psychometric properties of the credibility/expectancy questionnaire. J Behav Ther Exp Psychiatry. 2000;31:73–86.

Richman WL, Kiesler S, Weisband S, Drasgow F. A meta-analytic study of social desirability distortion in computer-administered questionnaires, traditional questionnaires, and interviews. J Appl Psychol. 1999;84:754–75.

Swiss Federal Council. Federal act on research involving human beings (human research act). Available from: https://www.admin.ch/opc/en/classified-compilation/20061313/index.html.

Sterne JAC, Savović J, Page MJ, Elbers RG, Blencowe NS, Boutron I, et al. RoB 2: a revised tool for assessing risk of bias in randomised trials. BMJ. 2019;366:l4898.

Muñoz Laguna J, Kurmann A, Hofstetter L, Nyantakyi E, Clack L, Bang H et al. Feasibility of blinding spinal manual therapy interventions among participants and outcome assessors: protocol for a blinding feasibility trial [under review 2023]. https://www.researchsquare.com/article/rs-3397311/v1

Sackett DL, Commentary. Measuring the success of blinding in RCTs: don’t, must, can’t or needn’t? Int J Epidemiol. 2007;36:664–5.

Hancock MJ, Maher CG, Latimer J, McAuley JH. Selecting an appropriate placebo for a trial of spinal manipulative therapy. Aust J Physiother. 2006;52:135–8.

Hohenschurz-Schmidt D, Vase L, Scott W, Annoni M, Ajayi OK, Barth J, et al. Recommendations for the development, implementation, and reporting of control interventions in efficacy and mechanistic trials of physical, psychological, and self-management therapies: the CoPPS Statement. BMJ. 2023;381:e072108.

Acknowledgements

The authors gratefully acknowledge Dr. Sarah Haile and Dr. Julia Braun for statistical support and thoughtful comments. The authors also acknowledge the doctoral students at the University of Zurich who kindly participated in the study.

Funding

No funding was provided for this study.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

CAH and JML had full access to all the data and take responsibility for data integrity and accuracy of the data analysis. CAH conceived the study idea, and CAH and JML managed and coordinated the planning and execution of the study within the setting of a practice-based doctoral-level course. TR, MAP, and CAH provided study resources and supervision. CAH, JML, EN, UB, KB, MD, FKLK, ML, AR, and MW participated in the design and execution of the study. MD, FKLK, and ML performed data curation and co-led the quantitative analysis. EN, KB, and MW performed the qualitative analysis. JML produced the first draft of the manuscript, with input from EN and CAH. All authors contributed to the reviewing, editing, and approval of the final version of the manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

The local independent research ethics committee of Canton Zurich (Kantonale Ethikkommission Zürich) deemed that ethical approval was not required for this methodological study of Swiss graduate students pursuant to Art. 2 (outside scope) of the Swiss Federal Act on Research involving Human Beings (Human Research Act, HRA). All participants provided voluntary electronic informed consent.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

CAH is an Associate Editor of Chiropractic & Manual Therapies. The editorial management system automatically blinded him from the submitted manuscript and he had no part in the editorial or peer-review process of this manuscript. CAH reports grants from the Swiss National Science Foundation (SNSF) and the European Centre for Chiropractic Research Excellence (ECCRE) outside the submitted work. JML reports funding from the European Cooperation in Science and Technology (COST) and the Graduate Campus of the University of Zurich outside the submitted work. All other authors report no financial relationships with any organisations that might have an interest in the submitted work in the previous three years. All authors report no other relationships or activities that could appear to have influenced the submitted work.

Additional information

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Electronic supplementary material

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Supplementary Material 1:

Trial protocol

Supplementary Material 2:

2010 CONSORT checklist

Supplementary Material 3:

Study information and consent form

Supplementary Material 4:

Figure S1

Supplementary Material 5:

Standard Operating Procedures

Supplementary Material 6:

Table S1

Supplementary Material 7:

Tables S2, S3, S4, and S5

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/. The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver (http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/) applies to the data made available in this article, unless otherwise stated in a credit line to the data.

About this article

Cite this article

Muñoz Laguna, J., Nyantakyi, E., Bhattacharyya, U. et al. Is blinding in studies of manual soft tissue mobilisation of the back possible? A feasibility randomised controlled trial with Swiss graduate students. Chiropr Man Therap 32, 3 (2024). https://doi.org/10.1186/s12998-023-00524-x

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s12998-023-00524-x