Abstract

Background

Previous research has investigated utilization rates, who sees chiropractors, for what reasons, and the type of care that chiropractors provide. However, these studies have not been comprehensively synthesized. We aimed to give a global overview by summarizing the current literature on the utilization of chiropractic services, reasons for seeking care, patient profiles, and assessment and treatment provided.

Methods

Systematic searches were conducted in MEDLINE, CINAHL, and Index to Chiropractic Literature using keywords and subject headings (MeSH or ChiroSH terms) from database inception to January 2016. Eligible studies: 1) were published in English or French; 2) were case series, descriptive, cross-sectional, or cohort studies; 3) described patients receiving chiropractic services; and 4) reported on the following theme(s): utilization rates of chiropractic services; reasons for attending chiropractic care; profiles of chiropractic patients; or, types of chiropractic services provided. Paired reviewers independently screened all citations and data were extracted from eligible studies. We provided descriptive numerical analysis, e.g. identifying the median rate and interquartile range (e.g., chiropractic utilization rate) stratified by study population or condition.

Results

The literature search retrieved 14,149 articles; 328 studies (reported in 337 articles) were relevant and reported on chiropractic utilization (245 studies), reason for attending chiropractic care (85 studies), patient demographics (130 studies), and assessment and treatment provided (34 studies). Globally, the median 12-month utilization of chiropractic services was 9.1% (interquartile range (IQR): 6.7%-13.1%) and remained stable between 1980 and 2015. Most patients consulting chiropractors were female (57.0%, IQR: 53.2%-60.0%) with a median age of 43.4 years (IQR: 39.6-48.0), and were employed (median: 77.3%, IQR: 70.3%-85.0%). The most common reported reasons for people attending chiropractic care were (median) low back pain (49.7%, IQR: 43.0%-60.2%), neck pain (22.5%, IQR: 16.3%-24.5%), and extremity problems (10.0%, IQR: 4.3%-22.0%). The most common treatment provided by chiropractors included (median) spinal manipulation (79.3%, IQR: 55.4%-91.3%), soft-tissue therapy (35.1%, IQR: 16.5%-52.0%), and formal patient education (31.3%, IQR: 22.6%-65.0%).

Conclusions

This comprehensive overview on the world-wide state of the chiropractic profession documented trends in the literature over the last four decades. The findings support the diverse nature of chiropractic practice, although common trends emerged.

Similar content being viewed by others

Background

Chiropractors practice in over 100 countries, in which 90 have established national chiropractic associations [1]. Chiropractic has become one of the most commonly used complementary and alternative medicine (CAM) therapies in the United States and Europe [2, 3]. Chiropractors provide a substantial portion of care for patients with many health conditions including low back and neck pain [4, 5]. They are also a major stakeholder in the health care expenditures of the United States and Denmark [6,7,8]; for example, in the United States in 2015, chiropractors provided 18.6 million clinical services under Medicare [9] and overall spending for chiropractic services was estimated at USD $12.5 billion [10].

Very few knowledge syntheses have summarized the results of studies describing the profile of chiropractic services and patients who seek their care [11,12,13]. Available reviews have only reported partial descriptions of chiropractic services and patients, utilization rates [14, 15] or reasons for attending chiropractic care [16]. Stakeholders of the profession would benefit from a current synthesis of research that comprehensively describes the profile of chiropractic practice and services provided to help inform priorities in education, research and workforce development. These priorities can aim to address the most common presenting conditions, facilitate workforce planning, establish professional norms, and guide curriculum design, quality improvement and guideline initiatives.

The objective of this scoping review was to document the current state of knowledge on the: 1) utilization of chiropractic services; 2) reasons for attending chiropractic care; 3) demographic and health profiles of chiropractic patients; and 4) types of chiropractic assessment and treatment provided worldwide.

Methods

We used scoping review methodology to collect and organize relevant information to address our broad research question and provide a comprehensive examination of the existing body of literature [17]. We employed rigorous methods based on the recommended framework for scoping reviews by Arksey and O’Malley and Levac et al. [18, 19].

STEP 1: Identifying the research question

Our scoping review was guided by the following broad research question: What is known about the utilization rate of chiropractic services, reasons for seeking care, patient profiles, and assessment and treatment provided?

STEP 2: Identifying relevant studies

We searched MEDLINE, CINAHL, and the Index of Chiropractic Literature (ICL) from database inception to January 14, 2016 using a combination of keywords and subject headings (MeSH or ChiroSH terms) relevant to four themes; utilization rate of chiropractic services, reasons for seeking care, patient profiles, and assessment and treatment provided. These themes were selected by the author team a priori with each representing an essential element of chiropractic practice. We first developed the search strategy in MEDLINE and subsequently adapted it to the other databases (Additional file 1: Appendix A). We used the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-analyses (PRISMA)[20] flow chart to track the number of studies at each stage of the review.

STEP 3: Study selection

Inclusion and Exclusion Criteria

We included studies: 1) published in the peer-reviewed literature in English or French; 2) were case series, descriptive, cross-sectional, or cohort studies; 3) described patients who received chiropractic services; and 4) reported at least one of the following: utilization rates of chiropractic services; reasons for attending chiropractic care; profiles of chiropractic patients; and types of chiropractic assessment and treatment provided. Studies were excluded if the methodology was not reported, if they were cadaveric or animal studies, or if they solely assessed profiles of chiropractors and did not report patient data, or clinical outcomes related to chiropractic care.

Screening and Agreement

Pairs of independent review authors screened the search results in two phases. All studies were screened using titles and abstracts during the first phase (phase I) to identify relevant, possibly relevant, and irrelevant citations. In the second phase of screening (phase II), possibly relevant articles were screened in full text to determine eligibility. For both phase I and II, a third review author was available to resolve discrepancies when forming consensus.

STEP 4: Data Charting

We extracted the following data from relevant studies (when available): 1) description of the study (study design, number of patients, country of origin, and study population); 2) description of the patient population (demographic information including age, sex, and occupation); 3) reasons for attending chiropractic services (clinical condition); 4) utilization rate of chiropractic services; 5) diagnosis or assessment procedures used by chiropractors; and 6) chiropractic treatment provided. One review author (PB) extracted the data, which were checked by a second review author to minimize error.

STEP 5: Collating, summarizing, and reporting the results

Analyzing the Data

We descriptively summarized the charted data to include the following:

-

1.

Descriptive numerical analysis: The nature and distribution of the studies were analyzed with regards to the total number of studies, year of publication, study design, country where studies were conducted, and study population.

-

2.

Summary of included study findings: We analysed the studies by categorising them into four themes: utilization rates; reasons for attending chiropractic care; profiles of chiropractic patients; and, types of chiropractic assessment and treatment provided. Across all studies within each theme, we identified the median rate and interquartile range (e.g., chiropractic utilization rate), percentage of patients, stratified by study population or condition.

-

3.

Implication of the results: We report the review findings according to the four themes to ensure that the results would have practical implications for future clinical chiropractic practice, research, and policy.

Results

Descriptive numerical analysis

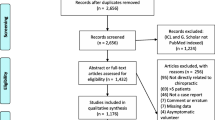

The search conducted on January 14th, 2016 yielded 14,149 publications, of which 12,000 were screened after removal of duplicates (Fig. 1). Phase I screening excluded 11,064 studies and a further 599 studies were excluded following phase II full text screening. A total of 337 articles (reported on 328 studies) were deemed relevant and were included in this review [11, 21,22,23,24,25,26,27,28,29,30,31,32,33,34,35,36,37,38,39,40,41,42,43,44,45,46,47,48,49,50,51,52,53,54,55,56,57,58,59,60,61,62,63,64,65,66,67,68,69,70,71,72,73,74,75,76,77,78,79,80,81,82,83,84,85,86,87,88,89,90,91,92,93,94,95,96,97,98,99,100,101,102,103,104,105,106,107,108,109,110,111,112,113,114,115,116,117,118,119,120,121,122,123,124,125,126,127,128,129,130,131,132,133,134,135,136,137,138,139,140,141,142,143,144,145,146,147,148,149,150,151,152,153,154,155,156,157,158,159,160,161,162,163,164,165,166,167,168,169,170,171,172,173,174,175,176,177,178,179,180,181,182,183,184,185,186,187,188,189,190,191,192,193,194,195,196,197,198,199,200,201,202,203,204,205,206,207,208,209,210,211,212,213,214,215,216,217,218,219,220,221,222,223,224,225,226,227,228,229,230,231,232,233,234,235,236,237,238,239,240,241,242,243,244,245,246,247,248,249,250,251,252,253,254,255,256,257,258,259,260,261,262,263,264,265,266,267,268,269,270,271,272,273,274,275,276,277,278,279,280,281,282,283,284,285,286,287,288,289,290,291,292,293,294,295,296,297,298,299,300,301,302,303,304,305,306,307,308,309,310,311,312,313,314,315,316,317,318,319,320,321,322,323,324,325,326,327,328,329,330,331,332,333,334,335,336,337,338,339,340,341,342,343,344,345,346,347,348,349,350,351,352,353,354,355,356,357,358]. Additional file 2: Appendix B summarizes the key aspects of each study into the four primary themes. Of the 328 relevant studies, 245 (74.7%) reported utilization rates of chiropractic services, 85 (25.9%) reported reasons for attending chiropractic care, 130 (39.6%) reported patient demographic information, 17 (5.2%) described assessment procedures provided, and 34 (11.0%) described types of chiropractic treatments provided.

Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-analyses (PRISMA) flow diagram of the scoping review. aOther reasons to exclude articles included issues with article reliability, responsiveness, and interpretability within the context of how the four themes were presented in our review. bSome articles reported more than one topic

We observed an increasing trend in the number of studies published between 1977 and January 2016, with 189 of the 328 studies (57.6%) published between 2005 and 2016 (Fig. 2). Most studies (291 of 328) were cross-sectional, 22 were retrospective cohort, 13 were prospective cohort, one was a chart review, and one was a descriptive study. The studies were most commonly conducted in the United States (n=183), Canada (n=47), Australia (n=41), United Kingdom (n=17), and Denmark (n=13).

Review findings

Utilization rate of chiropractic services

The utilization rate of chiropractic services at the regional or national levels over a 12-month period was reported in 52 studies (Fig. 3). The reported use of chiropractic services generally decreased over time in in Australia from 18.0% to 14.5% and increased over time in Canada and the United States from 10% to 11.7% and from 7.2% to 10.7% respectively. However, no clear worldwide trend of either increased or decreased chiropractic use was observed between 1980 and 2015.

Globally across all 52 studies at the regional/national level that reported utilization, the median 12-month use of chiropractic services was 9.1% (IQR: 6.7%-13.1%) and lifetime utilization was 22.2% (IQR: 12.8%-40.0%) (Table 1). Active military members and veterans used chiropractic services at a similar rate to the general population. Women, patients with chronic pain, and those with back pain (13.0%, 16.1%, and 31.0% respectively), utilized chiropractic services more often than the general population, whereas the pediatric (≤18 years) and older population (≥55 years) used chiropractic services less than the general population. In addition, 40 studies reported chiropractic utilization among unique populations related to specific age groups or health conditions, including psychiatric conditions, multiple sclerosis, stroke, HIV, diabetes, and gastrointestinal conditions. Twelve-month utilisation rates among these populations varied from 0% to 29%

Reasons for attending chiropractic care

In the general population, musculoskeletal conditions were the predominant reason for attending chiropractic care. The most common reasons were low back or back conditions (median of 49.7% patients (IQR: 43.0%-60.2%)) and neck conditions (22.5% (IQR: 16.3%-24.5%)). In the paediatric population (aged ≤18 years), the most common reason for attending chiropractic care was musculoskeletal conditions, with a median of 44.0% (IQR: 34.7%-57.0%) (Table 2). Only 3.1% (IQR: 1.6%-6.1%) of the general population sought chiropractic care for visceral/non-musculoskeletal conditions (Table 3).

Profiles of chiropractic patients

People who sought chiropractic care were more likely to be female (median 57.0%, IQR: 53.2%-60.0%) with a median age of 43.4 years (IQR: 39.6-48.0) (Table 4). In general, 77.3% (IQR: 70.3%-85.0%) of the chiropractic patient population were employed, and a smaller proportion were either retired (median 10.7% (IQR: 7.5%-16.0%)), unemployed (median 9.0% (IQR: 2.4%-16.5%)), or students (median 4.0% (IQR: 2.6%-10.6%)). People with disabilities constituted only 1.4% (median IQR: 1.4%-3.0%) of chiropractic patients.

Types of chiropractic services (assessment and treatment)

For diagnosis or assessment, static palpation was the most commonly used assessment procedure, reportedly used by 89.3% (IQR: 88.4%-95.0%) of chiropractors (Table 5). Other commonly used assessment procedures included motion palpation (86.5%, IQR: 78.0%-88.5%), spinal examination (79.5%, IQR: 79.0%-80.0%), orthopedic tests (71.8%, IQR: 35.5%-85.2%), and neurological examination (64.6%, IQR: 54.0%-77.0%). A third of chiropractors reported using x-rays as an assessment tool (median 35.0% (IQR: 26.5%-59.0%)), while magnetic resonance imaging and computerized tomography were used by only 1.3% (IQR: 1.0%-2.2%) and 1.9% (IQR: 0.3%-1.9%) of chiropractors, respectively.

Nearly four out of every five people (79.3%, IQR: 55.4%-91.3%) who sought chiropractic care received spinal manipulation, which was the most common treatment provided by chiropractors (Table 6). Other common treatments provided by chiropractors included soft-tissue therapy (35.1%, IQR: 16.5%-52.0%), and formal patient education (31.3%, IQR: 22.6%-65.6%).

Discussion

This scoping review of the chiropractic literature, the most comprehensive that we are aware of, identified 328 discrete studies from 337 articles related to the utilization rate of chiropractic services, reasons for attending chiropractic care, demographic and health profiles of chiropractic patients, and types of chiropractic assessment and treatment provided. The majority of these studies were published in the last decade (between 2005 and 2015), used a cross-sectional design, and were conducted in the United States, Canada, and Australia.

Our review’s finding of a regional/national 12-month utilization rate of chiropractic services (median of 9.1% across studies) was comparable to that of previous systematic reviews by Lawrence and Meeker (2007) and Cooper et al. (2013), who reported chiropractic utilization rates ranging between 6% and 12% [14, 15]. However, the variability among reported utilization rates between studies makes interpretation of our findings difficult. Relatively high use of chiropractic services among middle-aged women has also been noted by several prior investigations [359,360,361]. Patients who had chronic pain and back pain reported higher chiropractic utilization (16.1% and 31.0% respectively), when compared to that of the general population. Higher reported chiropractic utilization was also found by two previous systematic reviews that assessed chiropractic utilization of those who experienced chronic pain and back pain [362, 363]. As most studies assessed chiropractic utilization in the United States, Canada, or Australia, further research is needed to assess utilization in other countries.

Reasons for attending chiropractic care varied between studies. Hestbaek and Stochkendahl (2010) conducted a systematic review of the literature pertaining to the reasons why patients aged between 2-18 years attended chiropractic care. The authors concluded that musculoskeletal conditions, specifically spinal pain, were the main reasons for pediatric patients attending a chiropractor [16]. Our review findings show that musculoskeletal conditions, specifically those of the back and neck regions, are the main reasons for patients of all ages to consult chiropractors.

Our review found that chiropractors offer many types of treatments to their patients, but spinal manipulation was the most common treatment provided. The United States National Center for Health Statistics found that manipulation was the most commonly used provider-based CAM therapy among adults and children [364]. While spinal manipulative therapy (SMT) is an effective strategy for managing back pain [365], recent clinical practice guidelines [366,367,368] recommend clinicians use multimodal care including patient education and advice, manual therapy (including SMT and mobilisation), supervised and home exercise to increase the likelihood of favourable health outcomes. Our findings suggest that many chiropractors do provide multimodal care, consistent with clinical practice guidelines. Such multimodal care includes SMT, formal patient education, soft-tissue therapy, mechanically-assisted manipulative therapy, nutritional supplements, exercise instruction, ice, heat, mobilization/manual traction, orthopedic supports, electrical stimulation, therapeutic ultrasound, and acupuncture. Therefore, chiropractic care should not be considered consisting exclusively of spinal manipulation.

Stakeholders of the chiropractic profession need to be aware of the current state of knowledge to help inform their decision-making processes, promote evidence-based research informed practice, and to best serve those who seek chiropractic care. This review presents a comprehensive overview on the state of the chiropractic profession and has documented trends in the literature over time.

Strengths and Limitations

A strength of our study was the systematic process used to collect and summarize the available evidence from a large and diverse body of literature. A scoping review is the most appropriate method to collect and organize diverse information and to develop a picture of the existing evidence base [17]. Rigorous scoping review methodology can be used to bring theory to practice, and to reduce bias when informing stakeholders [369, 370]. We employed rigorous methods based on the recommended framework for scoping reviews by Arksey and O’Malley and Levac et al. [18, 19]. Moreover, we conducted systematic searches of the literature using multiple databases, a combination of key words and subject headings, and without date restrictions. Study selection was based on a set of clear inclusion and exclusion criteria to ensure that consensus between review authors was transparent and reproducible. Finally, we ensured that the charted data from each relevant study was accurate through a second check of the data.

Our scoping review has limitations. While a robust methodology was used, scoping reviews are a relatively new approach for which there is not yet a universal study definition or established methods [371]. However, the framework for scoping reviews published by Arksey and O’Malley in 2005 and expanded by Levac et al. in 2010 is being increasingly used across many disciplines and fields of study [372]. Despite conducting independent screening of systematic searches of multiple databases to identify relevant studies, our review did not review reference lists of included studies or employ hand searching nor were searches conducted in EmBase or AMED. This may have resulted in relevant studies being missed. Studies were excluded if not published in English or French, which may have resulted in missing relevant studies. However, it has been noted that chiropractic journals publish in English, which is recognized as the standard language of science, thereby reducing this risk [373]. Finally, the lack of critical appraisal of the methodology of the included studies may limit this review’s ability to report accurate results due to the inclusion of lower quality research. The implied systematic bias of these individual lower quality studies, and lower overall confidence in our results when summarizing findings, may have resulted in larger/faulty associations and imprecision around the estimates. However, several authors of scoping reviews have argued that by not addressing the issue of quality appraisal, scoping reviews are able to deal with a greater range of study designs and methodologies [374, 375]. The emphasis of a scoping review is on comprehensive coverage rather than on a particular standard of evidence [374, 375].

Conclusion

We employed rigorous scoping review methodology to document the current state of knowledge on the utilization rate of chiropractic services, demographic and health profiles of people receiving chiropractic care, and the assessment undertaken and treatment provided by chiropractors. Our findings reaffirm that the profile of chiropractic services and patients are diverse, yet common trends emerged. Across different countries and regions, the average 12-month utilization rate of chiropractic services was 9.1% with little change between 1980 and 2015. Musculoskeletal conditions, such as back and neck pain, were the predominant reason for people attending chiropractic care. Typically, chiropractic patients were female, aged 43.4 years, and employed. Four out of five patients who consulted a chiropractor received spinal manipulation; however, chiropractors also commonly provided other treatments including soft-tissue therapy and formal patient education.

References

World Federation of Chiropractic: The Current Status of the Chiropractic Profession: Report to the World Health Organization from the World Federation of Chiropractic. 2012.

Lester M: Chiropractic : An Introduction. 2012.

CAMDOC Alliance: The Regulatory Status of Complementary and Alternative Medicine for Medical Doctors in Europe. 2010.

Druss BG, Rosenheck RA. Association between use of unconventional therapies and conventional medical services. JAMA. 1999;282:651–6.

Eisenberg DM, Davis RB, Ettner SL, Appel S, Wilkey S, Van Rompay M, Kessler RC. Trends in alternative medicine use in the United States, 1990-1997: results of a follow-up national survey. JAMA. 1998;280:1569–75.

Nielsen OL, Kongsted A, Christensen HW. The chiropractic profession in Denmark 2010–2014: a descriptive report. Chiropr Man Therap. 2015;23:27.

Legorreta AP, Metz DR, Nelson CF, Ray S, Chermicoff HO, DiNubile NA. Comparative Analysis of Individuals With and Without Chiropractic Coverage: Patient Characteristics, Utilization, and Costs. Arch Intern Med. 2004;164:1985.

Haas M, Sharma R, Stano M. Cost-effectiveness of medical and chiropractic care for acute and chronic low back pain. J Manipulative Physiol Ther. 2005;28:555–63.

Whedon JM, Song Y, Davis MA. Trends in the use and cost of chiropractic spinal manipulation under Medicare Part B. Spine J. 2013;13:1449–54.

Association AC: American Chiropractic Association: 2015 Media Kit. Arlington, VA; 2015(October 2014).

Rupert RL, Manello D, Sandefur R. Maintenance care: health promotion services administered to US chiropractic patients aged 65 and older, part II. J Manipulative Physiol Ther. 2000;23:10–9.

Dunn A, Passmore S. Consultation Request Patterns, Patient Characteristics, and Utilization of Services within a Veterans Affairs Medical Center Chiropractic Clinic. Mil Med. 2008;173:599–603.

Gleberzon BJ. A narrative review of the published chiropractic literature regarding older patients from 2001-2010. J Can Chiropr Assoc. 2011;55:76–95.

Lawrence DJ, Meeker WC. Chiropractic and CAM utilization: a descriptive review. Chiropr Osteopat. 2007;15:2.

Cooper KL, Harris PE, Relton C, Thomas KJ. Prevalence of visits to five types of complementary and alternative medicine practitioners by the general population: A systematic review. Complement Ther Clin Pract. 2013;19:214–20.

Hestbaek L, Stochkendahl MJ. The evidence base for chiropractic treatment of musculoskeletal conditions in children and adolescents: The emperor’s new suit. Chiropr Osteopat. 2010;18:15.

Armstrong R, Hall BJ, Doyle J, Waters E. “Scoping the scope” of a cochrane review. J Public Health (Bangkok). 2011;33:147–50.

Arksey H, O’Malley L. Scoping studies: Towards a methodological framework. Int J Soc Res Methodol. 2005;8:19–32.

Levac D, Colquhoun H, O’Brien KK. Scoping studies: advancing the methodology. Implement Sci. 2010;5:1–9.

Moher D, Liberati A, Tetzlaff J, Altman DG, Grp P. Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses: The PRISMA Statement (Reprinted from Annals of Internal Medicine). Phys Ther. 2009;89:873–80.

Adams D, Whidden A, Honkanen M, Dagenais S, Clifford T, Baydala L, King WJ, Vohra S. Complementary and alternative medicine: a survey of its use in pediatric cardiology. C Open. 2014;2:E217–24.

Adams D, Schiffgen M, Kundu A, Dagenais S, Clifford T, Baydala L, King WJ, Vohra S. Patterns of Utilization of Complementary and Alternative Medicine in 2 Pediatric Gastroenterology Clinics. J Pediatr Gastroenterol Nutr. 2014;59:334–9.

Adams J, Sibbritt D, Broom A, Loxton D, Pirotta M, Humphreys J, Lui C-W. A comparison of complementary and alternative medicine users and use across geographical areas: A national survey of 1427 women. BMC Complement Altern Med. 2011;11:85.

Adams J, Sibbritt D, Broom A, Loxton D, Wardle J, Pirotta M, Lui CW. Complementary and alternative medicine consultations in urban and nonurban areas: A national survey of 1427 Australian women. J Manipulative Physiol Ther. 2013;36:12–9.

Adams J, Sibbritt D, Lui C-W. The use of complementary and alternative medicine during pregnancy: a longitudinal study of Australian women. Birth. 2011;38:200–6.

Aickin M, McCaffery A, Pugh G, Tick H, Ritenbaugh C, Hicks P, Pelletier KR, Cao J, Himick D, Monahan J. Description of a clinical stream of back-pain patients based on electronic medical records. Complement Ther Clin Pract. 2013;19:158–76.

Ailliet L, Rubinstein SM, De Vet HCW. Characteristics of chiropractors and their patients in Belgium. J Manipulative Physiol Ther. 2010;33:618–25.

Alcantara J. The presenting complaints of pediatric patients for chiropractic care: Results from a practice-based research network. Clin Chiropr. 2009;11:193–8.

Alcantara J, Ohm J, Kunz K, Alcantara JD. The Characterisation and Response to Care of Pregnant Patients Receiving Chiropractic Care within a Practice-based Research Network. Chiropr J Aust. 2012;42:60–7.

Al-Windi A. Determinants of complementary alternative medicine (CAM) use. Complement Ther Med. 2004;12:99–111.

Astin JA, Pelletier KR, Marie A, Haskell WL: Complementary and Alternative Medicine Use Among Elderly Persons : One-Year Analysis of a Blue Shield Medicare Supplement. 2000, 55:4–9.

Ayers SL, Kronenfeld JJ. Using factor analysis to create complementary and alternative medicine domains: an examination of patterns of use. Heal. 2010;14:234–52.

Bartlett E. Benchmarking the Clinical and Financial Characteristics of Chiropractic Offices. Top Clin Chiropr. 2001;8:13–9.

Berecki-Gisolf J, Collie A, McClure R. Reduction in health service use for whiplash injury after motor vehicle accidents in 2000-2009: Results from a defined population. J Rehabil Med. 2014;45:1034–41.

Blum C, Globe G, Terre L, Mirtz TA, Greene L, Globe D. Multinational survey of chiropractic patients: reasons for seeking care. J Can Chiropr Assoc. 2008;52:175–84.

Boon H, Stewart M, Kennard MA, Gray R, Sawka C, Brown JB, Mcwilliam C, Gavin A, Baron RA, Aaron D, Haines-kamka T. Use of Complementary/Alternative Medicine by Breast Cancer Survivors in Ontario : Prevalence and Perceptions. Am Soc Clin Oncol. 2000;18:2515–21.

Branson RA. Hospital-Based Chiropractic Integration Within a Large Private Hospital System in Minnesota: A 10-Year Example. J Manipulative Physiol Ther. 2009;32:740–8.

Breen AC. Chiropractors and the Treatment of Back Pain. Rheumatol Rehabil. 1977;16:46–53.

Bringsli M, Berntzen A, Olsen DB, Hestbæk L, Leboeuf-Yde C. The Nordic Maintenance Care Program: Maintenance care - what happens during the consultation? Observations and patient questionnaires. Chiropr Man Therap. 2012;20:25.

Broom AF, Kirby ER, Sibbritt DW, Adams J, Refshauge KM. Back pain amongst mid-age Australian women: A longitudinal analysis of provider use and self-prescribed treatments. Complement Ther Med. 2012;20:275–82.

Broom AF, Kirby ER, Sibbritt DW, Adams J, Refshauge KM. Use of complementary and alternative medicine by mid-age women with back pain: a national cross-sectional survey. BMC Complement Altern Med. 2012;12:1114.

Brown BT, Bonello R, Fernandez-Caamano R, Eaton S, Graham PL, Green H. Consumer characteristics and perceptions of chiropractic and chiropractic services in Australia: Results from a cross-sectional survey. J Manipulative Physiol Ther. 2014;37:219–29.

Brown BT, Bonello ROD, Fernandez-caamano R, Petra L, Eaton S, Green H. C hirop ractic in A ustralia : A S urv ey of the G eneral Public. 2013;43

Brunelli B, Gorson KC. The use of complementary and alternative medicines by patients with peripheral neuropathy. J Neurol Sci. 2004;218:59–66.

Bryant S, Atkins B, Bull P. Demographics and Diagnostic Profile of Patients Presenting to a University Chiropractic Outpatient Clinic. Chiropr J Aust. 2003;33:89–92.

Bryner P, Staeker P. Indigestion and Heartburn: A Descriptive Study of Prevalence in Persons Seeking Care from Chiropractors. J Manipulative Physiol Ther. 1996;19:317–23.

Cambron JA, Cramer GD, Winterstein J. Patient Perceptions of Chiropractic Treatment for Primary Care Disorders. J Manipulative Physiol Ther. 2007;30:11–6.

Carey TS, Garrett J, Jackman A, McLaughlin C, Fryer J, Smucker DR. The outcomes and costs of care for acute low back pain among patients seen by primary care practitioners, chiropractors, and orthopedic surgeons. The North Carolina Back Pain Project. N Engl J Med. 1995;333:913–7.

Carey T, Garrett JM, Jackman A. Recurrence and Care Seeking after Acute Back Pain : Results of a Long-Term Follow-Up Stud. Med Care. 1999;37:157–64.

Carey TS, Evans AT, Hadler NM, Kalsbeek WD, McLaughlin C, Fryer JG. Care-Seeking Among Individuals With Chronic Low Back Pain. Spine (Phila Pa 1976). 1995;20:312–7.

Carey TS, Evans AT, Hadler NM, Lieberman G, Kalsbeek WD, Jackman AM, Fryer JG, McNutt RA. Acute Severe Low Back Pain: A Population-based Study of Prevalence and Care-seeking. Spine. 1996;

Chao M, Wade C, Kronenberg F. Disclosure of Complementary and Alternative Medicine to Conventional Medical Providers: Variation by Race/Ethnicity and Type of CAM. J Natl Med Assoc. 2008;100:1341–9.

Cherkin DC, Deyo RA, Sherman KJ, Hart LG, Street JH, Hrbek A, Davis RB, Cramer E, Milliman B, Booker J, Mootz R, Barassi J, Kahn JR, Kaptchuk TJ, Eisenberg DM. Characteristics of Visits to Licensed Acupuncturists, Chiropractors, Massage Therapists, and Naturopathic Physicians. J Am Board Fam Pr. 2002;15:463–72.

Cheung CK, Wyman JF, Halcon LL. Use of Complementary and Alternative Therapies in Community-Dwelling Older Adults. J Altern Complement Med. 2007;13:997–1006.

Cleary PD. Chiropractic Use: A Test of Several Hypotheses. Am J Public Health. 1982;72:727–30.

Conboy L, Patel S, Kaptchuk TJ, Gottlieb B, Eisenberg D, Acevedo-Garcia D. Sociodemographic determinants of the utilization of specific types of complementary and alternative medicine: an analysis based on a nationally representative survey sample. J Altern Complement Med. 2005;11:977–94.

Côté P, Cassidy JD, Carroll L. The treatment of neck and low back pain: who seeks care? who goes where? Med Care. 2001;39:956–67.

Coulter ID, Hurwitz EL, Adams AH, Genovese BJ, Hays R, Shekelle PG. Patients using chiropractic in North America: who are they, and why are they in chiropractic care? Spine (Phila Pa 1976). 2002;27:291–7.

Coulter ID, Shekelle PG. Chiropractic in North America: A Descriptive Analysis. J Manipulative Physiol Ther. 2005;28:83–9.

Coulter ID, Hurwitz EL, Aronow HU, Cassata DM, Beck JC. Chiropractic Patients in a Comprehensive Home-Based Geriatric Assessment, Follow-up and Health Promotion Program. Top Clin Chiropr. 1996;3:46–55.

Davis MA, Sirovich BE, Weeks WB. Utilization and expenditures on chiropractic care in the United States from 1997 to 2006. Health Serv Res. 2010;45:748–61.

Deyo RA, Tsui-Wu YJ. Descriptive epidemiology of low-back pain and its related medical care in the United States. Spine. 1987:264–8.

Dimmock S, Troughton PR, Bird HA. Factors predisposing to the resort of complementary therapies in patients with fibromyalgia. Clin Rheumatol. 1996;15:478–82.

Doering JH, Reuner G, Kadish NE, Pietz J, Schubert-Bast S. Pattern and predictors of complementary and alternative medicine (CAM) use among pediatric patients with epilepsy. Epilepsy Behav. 2013;29:41–6.

D’Onise K, Haren MT, Misan GMH, McDermott RA. Who uses complementary and alternative therapies in regional South Australia? Evidence from the Whyalla Intergenerational Study of Health. Aust Heal Rev. 2013;37:104–11.

Drivdahl CE, Miser WF. The use of alternative health care by a family practice population. J Am Board Fam Pract. 1998;11:193–9.

Druss BG, Marcus SC, Olfson M, Tanielian T, Pincus HA. Trends in care by nonphysician clinicians in the United States. N Engl J Med. 2003;348:130–7.

Dunn AS, Passmore SR. Consultation request patterns, patient characteristics, and utilization of services within a Veterans Affairs medical center chiropractic clinic. Mil Med. 2008;173:599–603.

Dunn AS, Towle JJ, McBrearty P, Fleeson SM. Chiropractic Consultation Requests in the Veterans Affairs Health Care System: Demographic Characteristics of the Initial 100 Patients at the Western New York Medical Center. J Manipulative Physiol Ther. 2006;29:448–54.

Eaves ER, Sherman KJ, Ritenbaugh C, Hsu C, Nichter M, Turner JA, Cherkin DC. A qualitative study of changes in expectations over time among patients with chronic low back pain seeking four CAM therapies. BMC Complement Altern Med. 2015;15:12.

Ebrall P. A Descriptive Report of the Case-Mix within Australian Chiropractic Practice, 1992. Chiropr J Aust. 1993;23:92–7.

Eirikstoft H, Kongsted A. Patient characteristics in low back pain subgroups based on an existing classification system. A descriptive cohort study in chiropractic practice. Man Ther. 2014;19:65–71.

Eisenberg DM, Davis RB, Ettner SI, Appel S, Wilkey S, Rompay MV, RC K. Trends in alternative medicine use in the United States, 1990 - results of a follow-up national survey. Jama. 1997;280:1569–75.

Eisenberg DM, Kessler RC, Foster C, Norlock FE, Calkins DR, Delbanco TL. Unconventional Medicine in the United States. N Engl J Med. 1993;328:246–52.

Elder C, DeBar L, Ritenbaugh C, Vollmer W, Deyo RA, Dickerson J, Kindler L. Acupuncture and chiropractic care: utilization and electronic medical record capture. Am J Manag Care. 2015;21:e414–21.

Elder NC, Gillcrist A, Minz R. Use of Alternative Health Care by Family Practice Patients. Arch Fam Med. 1997;6:181–4.

Elkins G, Rajab MH, Marcus J. Complementary and alternative medicine use by psychiatric inpatients. Psychol Rep. 2005;96:163–6.

Ellis WB, Bonello RP. A Comparison of the Patient Demographics of Victorian Chiropractic and Osteopathic Clinics: A Pilot Study. COMSIG Rev. 1994;3:48–53.

Emslie MJ, Campbell MK, Walker KA. Changes in public awareness of, attitudes to, and use of complementary therapy in North East Scotland: Surveys in 1993 and 1999. Complement Ther Med. 2002;10:148–53.

Engel RM, Brown BT, Swain MS, Lystad RP. The provision of chiropractic, physiotherapy and osteopathic services within the Australian private health-care system: a report of recent trends. Chiropr Man Therap. 2014;22:1–7.

Enyinnaya EI, Anderson JG, Merwin EI, Taylor AG. Chiropractic use, health care expenditures, and health outcomes for rural and nonrural individuals with arthritis. J Manipulative Physiol Ther. 2012;35:515–24.

Ernst E, White A. The BBC survey of complementary medicine use in the UK. Complement Ther Med. 2000;8:32–6.

Evans A, Duncan B, McHugh P, Shaw J, Wilson C. Impatients’ use, understanding, and attitudes towards traditional, complementary and alternative therapies at a provincial New Zealand hospital. N Z Med J. 2008;121:21–34.

Factor-Litvak P, Cushman L, Kronenberg F, Wade C, Kalmuss D. Use of complementary and alternative medicine among women in New York City: a pilot study. J Altern Complement Med. 2001;7:659–66.

Fadanelli G, Vittadello F, Martini G, Zannin ME, Zanon G, Zulian F. Complementary and Alternative Medicine (CAM) in paediatric rheumatology: a European perspective. Clin Exp Rheumatol. 2012;30:132–6.

Fautrel B, Adam V, St-Pierre Y, Joseph L, Clarke AE, Penrod JR. Use of complementary and alternative therapies by patients self-reporting arthritis or rheumatism: Results from a nationwide Canadian survey. J Rheumatol. 2002;29:2435–41.

Fawcett J, Sidney JS, Hanson MJ, Riley-Lawless K. Use of alternative health therapies by people with multiple sclerosis: an exploratory study. Holistic nursing practice. 1994:36–42.

Featherstone C, Godden D, Selvaraj S, Emslie M, Took-Zozaya M. Characteristics associated with reported CAM use in patients attending six GP practices in the Tayside and Grampian regions of Scotland: A survey. Complement Ther Med. 2003;11:168–76.

Feinglass J, Lee C, Rogers M, Temple LM, Nelson C, Chang RW. Complementary and Alternative Medicine Use for Arthritis Pain in 2 Chicago Community Areas. Clin J Pain. 2007;23:744–9.

Feldman DE, Duffy C, De Civita M, Malleson P, Philibert L, Gibbon M, Ortiz-Alvarez O, Dobkin PL. Factors associated with the use of complementary and alternative medicine in juvenile idiopathic arthritis. Arthritis Rheum. 2004;51:527–32.

Feldman RH. The Use of Complementary and Alternative Medicine Practices Among Australian University Students. Complement Health Pract Rev. 2004;9:173–9.

Fernandez CV, Stutzer CA, MacWilliam L, Fryer C. Alternative and complementary therapy use in pediatric oncology patients in British Columbia: prevalence and reasons for use and nonuse. J Clin Oncol. 1998;16:1279–86.

Feuerstein M, Marcus SC, Huang GD. National trends in nonoperative care for nonspecific back pain. Spine J. 2004;4:56–63.

Fitzcharles M-A, Esdaile JM. Nonphysician Practitioner Treatments and Fibromyalgia Syndrome. J Rheumatol. 1997;24:937–40.

Flaherty JH, Takahashi R, Teoh J, Kim JI, Habib S, Ito M, Matsushita S. Use of alternative therapies in older outpatients in the United States and Japan: prevalence, reporting patterns, and perceived effectiveness. J Gerontol A Biol Sci Med Sci. 2001;56:M650–5.

Fleming S, Rabago DP, Mundt MP, Fleming MF. CAM therapies among primary care patients using opioid therapy for chronic pain. BMC Complement Altern Med. 2007;7:15.

Fong DPS, Fong LKS. Usage of complementary medicine among children. Aust Fam Physician. 2002;31:388–91.

Fortier MA, Gillis S, Gomez SH, Wang S-M, Tan ET, Kain ZN. Attitudes toward and use of complementary and alternative medicine among Hispanic and white mothers. Altern Ther Health Med. 2014;20:13–9.

Foster DF, Phillips RS, Hamel MB, Eisenberg DM. Alternative medicine use in older Americans. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2000;48:1560–5.

Fouladbakhsh J, Stommel M. Comparative analysis of complementary and alternative medicine (CAM) use in the US cancer and noncancer populations. Eur J Integr Med. 2008;1S:S9–41.

Fouladbakhsh JM, Stommel M, Given BA, Given CW. Predictors of Use of Complementary and Alternative Therapies Among Patients With Cancer. Oncol Nurs Forum. 2005;32:1115–22.

Fox P, Butler M, Coughlan B, Murray M, Boland N, Hanan T, Murphy H, Forrester P, O’Brien M, O’Sullivan N. Using a mixed methods research design to investigate complementary alternative medicine (CAM) use among women with breast cancer in Ireland. Eur J Oncol Nurs. 2013;17:490–7.

Frawley J, Adams J, Sibbritt D, Steel A, Broom A, Gallois C. Prevalence and determinants of complementary and alternative medicine use during pregnancy: Results from a nationally representative sample of Australian pregnant women. Aust New Zeal J Obstet Gynaecol. 2013;53:347–52.

French SD, Charity MJ, Forsdike K, Gunn JM, Polus BI, Walker BF, Chondros P, Britt HC. Chiropractic Observation and Analysis Study (COAST): providing an understanding of current chiropractic practice. Med J Aust. 2012;199:687–91.

French SD, Densley K, Charity MJ, Gunn J. Who uses Australian chiropractic services? Chiropr Man Therap. 2013;21:31.

Frenkel M, Ben Arye E, Carlson C, Sierpina V. Integrating Complementary and Alternative Medicine Into Conventional Primary Care: The Patient Perspective. Explor J Sci Heal. 2008;4:178–86.

Friedman T, Slayton WB, Allen LS, Pollock BH, Dumont-Driscoll M, Mehta P, Graham-Pole J. Use of alternative therapies for children with cancer. Pediatrics. 1997;100:E1.

Furler MD, Einarson TR, Walmsley S, Millson M, Bendayan R. Use of complementary and alternative medicine by HIV-infected outpatients in Ontario, Canada. AIDS Patient Care STDS. 2003;17:155–68.

Furlow ML, Patel DA, Sen A, Liu JR. Physician and patient attitudes towards complementary and alternative medicine in obstetrics and gynecology. BMC Complement Altern Med. 2008;8:35.

Gaedeke RM, Tootelian DH, Holst C. Alternative medicine among college students. J Hosp Mark. 1999;13:107–18.

Gaffney L, Smith C. The Views of Pregnant Women Towards the Use of Complementary Therapies and Medicines. Birth Issues. 2004;13:43–50.

Ganguli SC, Cawdron R, Irvine EJ. Alternative Medicine Use by Canadian Ambulatory Gastroenterology Patients: Secular Trend or Epidemic? Am J Gastroenterol. 2004;99:319–26.

Garrow D, Egede LE. National patterns and correlates of complementary and alternative medicine use in adults with diabetes. J Altern Complement Med. 2006;12:895–902.

Gaumer G, Gemmen E. Chiropractic Users and Nonusers: Differences in Use, Attitudes, and Willingness to Use Nonmedical Doctors for Primary Care. J Manipulative Physiol Ther. 2006;29:529–39.

George S, Jackson JL, Passamonti M. Complementary and alternative medicine in a military primary care clinic: a 5-year cohort study. Mil Med. 2011;176:685–8.

Gerasimidis K, Mcgrogan P, Hassan K, Edwards CA. Dietary modifications, nutritional supplements and alternative medicine in paediatric patients with inflammatory bowel disease. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2008;27:155–65.

Geva H, Bar-Sela G, Dashkowsky Z, Mashiach T, Robinson E. The use of complementary and alternative therapies by cancer patients in northern Israel. Isr Med Assoc J. 2005;7:243–7.

Gkolfinopoulos V, Byfield D, Phil M, McCarthy PW. A survey of low back pain patients in chiropractic practices in South Wales. Eur J Chiropr. 2003;49:289–94.

Goertz C, Marriott BP, Finch MD, Bray RM, Williams TV, Hourani LL, Hadden LS, Colleran HL, Jonas WB. Military Report More Complementary and Alternative Medicine Use than Civilians. J Altern Complement Med. 2013;19:509–17.

Goldman AW, Cornwell B. Social network bridging potential and the use of complementary and alternative medicine in later life. Soc Sci Med. 2015;140:69–80.

Goldstein MS, Brown ER, Ballard-Barbash R, Morgenstern H, Bastani R, Lee J, Gatto N, Ambs A. The use of complementary and alternative medicine among California adults with and without cancer. Evidence-based Complement Altern Med. 2005;2:557–65.

Goldstein MS, Lee JH, Ballard-barbash R, Brown ER. The use and perceived benefit of complementary and alternative medicine among Californians with cancer. Psychooncology. 2008;17:19–25.

Gore M, Tai KS, Sadosky A, Leslie D, Stacey BR. Use and Costs of Prescription Medications and Alternative Treatments in Patients with Osteoarthritis and Chronic Low Back Pain in Community-Based Settings. Pain Pract. 2012;12:550–60.

Gore-felton C, Vosvick M, Power R, Koopman C, Ashton E, Bachmann MH, Israelski D, Spiegel D. Alternative Therapies: A Common Practice Among Men and Women Living With HIV. AIDS Care. 2003;14:17–27.

Graham ME, Brake MK, Taylor SM, Flowerdew G, Hong P. Complementary and alternative medicine use among patients presenting to a pediatric otolaryngology clinic. Int J Pediatr Otorhinolaryngol. 2013;77:721–5.

Graham RE, Ahn AC, Davis RB, O’Connor BB, Eisenberg DM, Phillips RS. Use of complementary and alternative medical therapies among racial and ethnic minority adults: results from the 2002 National Health Interview Survey. J Natl Med Assoc. 2005;97:535–45.

Gray CM, Tan AW, Pronk NP. Complementary and alternative medicine use among health plan members. A cross-sectional survey. Eff Clin Pract. 2002;5:17–22.

Gray RE, Fitch M, Goel V, Franssen E, Labrecque M. Utilization of Complementary/Alternative Services by Women with Breast Cancer. J Health Soc Policy. 2003;16:75–84.

Greenfield SM, Innes MA, Allan TF, Wearn AM. First year medical students’ perceptions and use of complementary and alternative medicine. Complement Ther Med. 2002;10:27–32.

Grossoehme DH, Cotton S, McPhail G. Use and Sanctification of Complementary and Alternative Medicine by Parents of Children with Cystic Fibrosis. J Health Care Chaplain. 2013;19:22–32.

Grzywacz JG, Suerken CK, Quandt SA, Bell RA, Lang W, Arcury TA. Older Adults’ Use of Complementary and Alternative Medicine for Mental Health: Findings from the 2002 National Health Interview Survey. J Altern Complement Med. 2006;12:467–73.

Gulla J, Singer AJ. Use of alternative therapies among emergency department patients. Ann Emerg Med. 2000;35:226–8.

Habermann TM, Thompson CA, Laplant BR, Brent A, Janney CA, Clark MM, Rummans TA, Maurer MJ, Sloan JA, Geyer SM, Cerhan JR. Complementary and alternative medicine use among long-term survivors: a pilot study. Am J Hematol. 2009;84:795–8.

Hagen LEM, Schneider R, Stephens D, Modrusan D, Feldman BM. Use of complementary and alternative medicine by pediatric rheumatology patients. Arthritis Rheum. 2003;49:3–6.

Hall HR, Jolly K. Women’s use of complementary and alternative medicines during pregnancy: A cross-sectional study. Midwifery. 2014;30:499–505.

Hamm E, Muramoto M, Howerter A, Floden L, Govindarajan L. Use of Provider-Based Complementary and Alternative Medicine by Adult Smokers in the United States: Comparison From the 2002 and 2007 NHIS Survey. Am J Heal Promot. 2014;29:127–31.

Hanley MA, Ehde DM, Campbell KM, Osborn B, Smith DG. Self-reported treatments used for lower-limb phantom pain: Descriptive findings. Arch Phys Med Rehabil. 2006;87:270–7.

Hann DM, Baker F, Roberts CS, Witt C, McDonald J, Livingston M, Ruiterman J, Ampela R, Crammer C, Kaw O. Use of Complementary Therapies Among Breast and Prostate Cancer Patients During Treatment: A Multisite Study. Integr Cancer Ther. 2005;4:294–300.

Hann D. Long-term Breast Cancer Survivors’ Use of Complementary Therapies: Perceived Impact on Recovery and Prevention of Recurrence. Integr Cancer Ther. 2005;4:14–20.

Hansen JP, Futch DB. Chiropractic Services in a Staff Model HMO: Utilization and Satisfaction. HMO Pract. 1997;11:39–42.

Hanssen B, Grimsgaard S, Launsø L, Fønnebø V, Falkenberg T, Rasmussen NK. Use of complementary and alternative medicine in the scandinavian countries. Scand J Prim Health Care. 2005;23:57–62.

Harding S, Swait G, Johnson I, Cunliffe C. Utilisation of CAM by runners in the UK: A retrospective survey among non-elite marathon runners. Clin Chiropr. 2009;12:61–6.

Harrigan R, Mbabuike N. Use of Provider Delivered Complementary and Alternative Therapies in Hawai â€TM i : Results of the Hawai â€TM i Health Survey. Hawaii Med J. 2006;65:130–51.

Harrington JW, Rosen L, Garnecho ANA, Patrick PA. Parental perceptions and use of complementary and alternative medicine practices for children with autistic spectrum disorders in private practice. J Dev Behav Pediatr. 2006;27(2 Suppl):S156–61.

Hartmann N, Neininger MP, Bernhard MK, Syrbe S, Nickel P, Merkenschlager A, Kiess W, Bertsche T, Bertsche A. Use of complementary and alternative medicine (CAM) by parents in their children and adolescents with epilepsy - Prevelance, predictors and parents’ assessment. Eur J Paediatr Neurol. 2016;20:11–9.

Hartvigsen J, Bolding-Jensen O, Hviid H, Grunnet-Nilsson N. Danish chiropractic patients then and now - A comparison between 1962 and 1999. J Manipulative Physiol Ther. 2003;26:65–9.

Hartvigsen J, Sorensen LP, Graesborg K, Grunnet-Nilsson N. Chiropractic patients in Denmark: A short description of basic characteristics. J Manipulative Physiol Ther. 2002;25:162–7.

Hawk C, Long CR, Boulanger KT. Prevalence of nonmusculoskeletal complaints in chiropractic practice: Report from a practice-based research program. J Manipulative Physiol Ther. 2001;24:157–69.

Hawk C, Byrd L, Jansen RD, Long CR. Use of complementary healthcare practices among chiropractors in the United States: A survey. Altern Ther Health Med. 1999;5:56–62.

Hawk C, Dusio M. A Survey of 492 U.S. Chiropractors on Primary Care and Prevention-Related Issues. J Manipulative Physiol Ther. 1995;18:57–64.

Hawk C, Long CR. Factors Affecting Use of Chiropractic Services in Seven Midwestern States of the United States. J Rural Heal. 1999;15:233–9.

Hawk C, Long CR, Boulanger KT, Morschhauser E, Fuhr AW. Chiropractic Care for Patients Aged 55 Years and Older: Report from a Practice-Based Research Program. JAGS. 2000;48:534–45.

Hayden J, Mior S, Verhoef M. Evaluation of chiropractic management of pediatric patients with low back pain: A prospective cohort study. J Manipulative Physiol Ther. 2003;26:1–8.

Hazra M, Noh S, Boon H, Taylor A, Moss K, Mamo DC. Complementary and alternative medicine in psychotic disorders. J Complement Integr Med. 2010;7:1–15.

Heathcote JD, West JH, Cougar Hall P, Trinidad DR. Religiosity and Utilization of Complementary and Alternative Medicine Among Foreign-Born Hispanics in the United States. Hisp J Behav Sci. 2011;33:398–408.

Helyer LK, Chin S, Chui BK, Fitzgerald B, Verma S, Rakovitch E, Dranitsaris G, Clemons M. The use of complementary and alternative medicines among patients with locally advanced breast cancer--a descriptive study. BMC Cancer. 2006;6:1–25.

Henderson JW, Donatelle RJ. Complementary and alternative medicine use by women after completion of allopathic treatment for breast cancer. Altern Ther Heal Med. 2004;10(Jan):52–7.

Hestbaek L, Jørgensen A, Hartvigsen J. A Description of Children and Adolescents in Danish Chiropractic Practice: Results from a Nationwide Survey. J Manipulative Physiol Ther. 2009;32:607–15.

Hestbaek L, Munck A, Hartvigsen L, Jarbøl DE, Søndergaard J, Kongsted A. Low back pain in primary care: a description of 1250 patients with low back pain in danish general and chiropractic practice. Int J Family Med 2014. 2014:106102.

Hilsden R. Complementary and alternative medicine use by Canadian patients with inflammatory bowel disease: results from a national survey. Am J Gastroenterol. 2003;98:1563–8.

Hirsh AT, Kratz AL, Engel JM, Jensen MP. Survey Results of Pain Treatments in Adults with Cerebral Palsy. Am J Phys Med Rehabil. 2011;90:207–16.

Ho DV, Nguyen J, Liu MA, Nguyen AL, Kilgore DB. Use of and Interests in Complementary and Alternative Medicine by Hispanic Patients of a Community Health Center. J Am Board Fam Med. 2015;28:175–83.

Ho KY, Jones L, Gan TJ. The effect of cultural background on the usage of complementary and alternative medicine for chronic pain management. Pain Physician. 2009;12:685–8.

Hodges BR, Cambron JA, Klein RM, Madigan DM. Prevalence of nonmusculoskeletal versus musculoskeletal cases in a chiropractic student clinic. J Chiropr Educ. 2013;27:130611135952007.

Hollyer T, Boon H, Georgousis A, Smith M, Einarson A. The use of CAM by women suffering from nausea and vomiting during pregnancy. BMC Complement Altern Med. 2002;2:5.

Holt K, Beck R. Chiropractic Patients Presenting to the New Zealand College of Chiropractic Teaching Clinic: A Short Description of Patients and Patient Complaints. Chiropr J Aust. 2005;35:122–4.

Honda K, Jacobson JS. Use of complementary and alternative medicine among United States adults: The influences of personality, coping strategies, and social support. Prev Med (Baltim). 2005;40:46–53.

Hori S, Mihaylov I, Vasconcelos JC, McCoubrie M. Patterns of complementary and alternative medicine use amongst outpatients in Tokyo. Japan. BMC Complement Altern Med. 2008;8:14.

Hsiao A-F, Wong MD, Kanouse DE, Collins RL, Liu H, Andersen RM, Gifford AL, McCutchan A, Bozzette SA, Shapiro MF, Wenger NS. Complementary and Alternative Medicine Use and Substitiution for Conventional Therapy by HIV-Infected Patients. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr. 2003;33:157–65.

Hsu MC, Creedy D, Moyle W, Venturato L, Tsay SL, Ouyang WC. Use of Complementary and Alternative Medicine among adult patients for depression in Taiwan. J Affect Disord. 2008;111:360–5.

Hughes SC, Wingard DL. Children’s Visits to Providers of Complementary and Alternative Medicine in San Diego. Ambul Pediatr. 2006;6:293–6.

Humpel N, Jones SC. Development of a Comprehensive Questionnaire of Complementary and Alternative Medicine Use Among Cancer Patients and Survivors. Complement Health Pract Rev. 2005;10:163–74.

Humphreys BK, Peterson CK, Muehlemann D, Haueter P. Are Swiss chiropractors different than other chiropractors? Results of the job analysis survey 2009. J Manipulative Physiol Ther. 2010;33:519–35.

Hung A, Kang N, Bollom A, Wolf JL, Lembo A. Complementary and Alternative Medicine Use Is Prevalent Among Patients with Gastrointestinal Diseases. Dig Dis Sci. 2015;60:1883–8.

Hunt KJ, Coelho HF, Wider B, Perry R, Hung SK, Terry R, Ernst E. Complementary and alternative medicine use in England: Results from a national survey. Int J Clin Pract. 2010;64:1496–502.

Hunter D, Oates R, Gawthrop J, Bishop M, Gill S. Complementary and alternative medicine use and disclosure amongst Australian radiotherapy patients. Support Care Cancer. 2014;22:1571–8.

Hurvitz EA, Leonard C, Ayyangar R, Nelson VS. Complementary and alternative medicine use in families of children with cerebral palsy. Dev Med Child Neurol. 2003;45:364–70.

Hurwitz EL, Coulter ID, Adams AH, Genovese BJ, Shekelle PG. Use of chiropractic services from 1985 through 1991 in the United States and Canada. Am J Public Health. 1998;88:771–6.

Hurwitz EL, Chiang L-M. A comparative analysis of chiropractic and general practitioner patients in North America: findings from the joint Canada/United States Survey of Health, 2002-03. BMC Health Serv Res. 2006;6:49.

Ivanova JI, Birnbaum HG, Schiller M, Kantor E, Johnstone BM, Swindle RW. Real-world practice patterns, health-care utilization, and costs in patients with low back pain: the long road to guideline-concordant care. Spine J. 2011;11:622–32.

Jacob T, Zeev A, Epstein L. Low back pain--a community-based study of care-seeking and therapeutic effectiveness. Disabil Rehabil. 2003;25:67.

Jacobs P, Schopflocher D, Klarenbach S, Golmohammadi K, Ohinmaa A. A health production function for persons with back problems: results from the Canadian Community Health Survey of 2000. Spine (Phila Pa 1976). 2004;29:2304–8.

Jacobson BH, Gemmell HA. A Survey of Chiropractors in Oklahoma. J Chiropr Educ. 1999;13:137–42.

Jacobson IG, White MR, Smith TC, Smith B, Wells TS, Gackstetter GD, Boyko EJ. Self-Reported Health Symptoms and Conditions Among Complementary and Alternative Medicine Users in a Large Military Cohort. Ann Epidemiol. 2009;19:613–22.

James FR, Large RG. Chronic pain and the use of health services. N Z Med J. 1992;105:196–8.

Jamison JR. Dietary diversity: A case study of fruit and vegetable consumption by chiropractic patients. J Manipulative Physiol Ther. 2003;26:383–9.

Jamison JR. Self-care: An Australian case study of chiropractic patients. J Chiropr Med. 2002;1:49–53.

Jamison JR, Davies N. Paediatric Patients Seeking Chiropractic Care: An Australian Case Study. Chiropr J Aust. 2005;35:143–6.

Jawahar R, Yang S, Eaton CB, McAlindon T, Lapane KL. Gender-Specific Correlates of Complementary and Alternative Medicine Use for Knee Osteoarthritis. J Women’s Heal. 2012;21:1091–9.

Jean D, Cyr C. Use of Complementary and Alternative Medicine in a General Pediatric Clinic. Pediatrics. 2007;120:e138–41.

Jensen KM, Rasmussen LR. Children in Danish chiropractic clinics: a descriptive questionnaire study. Eur J Chiropr. 1989;37:117–24.

Jordan JM, Bernard SL, Callahan LF, Kincade JE, Konrad TR, DeFriese GH. Self-reported arthritis-related disruptions in sleep and daily life and the use of medical, complementary, and self-care strategies for arthritis: the National Survey of Self-care and Aging. Arch Fam Med. 2000;9:143–9.

Jordan KM, Sawyer S, Coakley P, Smith HE, Cooper C, Arden NK. The use of conventional and complementary treatments for knee osteoarthritis in the community. Rheumatology. 2004;43:381–4.

Kaboli PJ, Doebbeling BN, Saag KG, Rosenthal GE. Use of complementary and alternative medicine by older patients with arthritis: a population-based study. Arthritis Rheum. 2001;45:398–403.

Kaeser M, Hawk C, Anderson M. Patient characteristics upon initial presentation to chiropractic teaching clinics: A descriptive study conducted at one university. J Chiropr Educ. 2014;28:146–51.

Kalaaji AN, Wahner-Roedler DL, Sood A, Chon TY, Loehrer LL, Cha SS, Bauer BA. Use of complementary and alternative medicine by patients seen at the dermatology department of a tertiary care center. Complement Ther Clin Pract. 2012;18:49–53.

Karakurum Göksel B, Coşkun O, Ucler S, Karatas M, Ozge A, Ozkan S. Use of complementary and alternative medicine by a sample of Turkish primary headache patients. Aǧrı Ağrı Derneği’nin Yayın organıdır = J Turkish Soc Algol. 2014;26:1–7.

Kassak K. The Pracitce of Chiropractic in South Dakota: A Survey of Chiropractors. J Manipulative Physiol Ther. 1994;17:523–9.

Katz P, Lee F. Racial/ethnic differences in the use of complementary and alternative medicine in patients with arthritis. J Clin Rheumatol. 2007;13:3–11.

Keegan L. Use of Alternative Therapies Among Mexican Americans in the Texas Rio Grande Valley. J Holist Nurs. 1996;14:277–94.

Keenan NL, Mark S, Fugh-Berman A, Browne D, Kaczmarczyk J, Hunter C. Severity of menopausal symptoms and use of both conventional and complementary/alternative therapies. Menopause. 2003;10:507–15.

Kelner M, Wellman B. Who Seeks Alternative Health Care? A Profile of the Users of Five Modes of Treatment. J Altern Complement Med. 1997;3:127–40.

Kessler RC, Soukup J, Davis RB, Foster DF. Wilkey S a, Van Rompay MI, Eisenberg DM: The use of complementary and alternative therapies to treat anxiety and depression in the United States. Am J Psychiatry. 2001;158:289–94.

Kilbourne A, Copeland L, Zeber J, Bauer M, Lasky E, Good C. Determinants of Complementary and Alternative Medicine Use by Patients with Bipolar Disorder. Gen Psychiatry. 2007;40:104–15.

Kim HA, Seo Y. Il: Use of complementary and alternative medicine by arthritis patients in a university hospital clinic serving rheumatology patients in Korea. Rheumatol Int. 2003;23:277–81.

Kim J, Chan MM. Factors Influencing Preferences for Alternative Medicine by Korean Americans. Am J Chin Med. 2004;32:321–9.

King MO, Pettigrew AC. Complementary and alternative therapy use by older adults in three ethnically diverse populations: a pilot study. Geriatr Nurs. 2004;25:30–7.

Kinge JM, Knudsen AK, Skirbekk V, Vollset SE. Musculoskeletal disorders in Norway: prevalence of chronicity and use of primary and specialist health care services. BMC Musculoskelet Disord. 2015;16:75.

Kirby E, Broom A, Sibbritt D, Adams J, Refshauge K. A national cross-sectional survey of back pain care amongst Australian women aged 60-65. Eur J Integr Med. 2012;5:36–43.

Kirby ER, Broom AF, Sibbritt DW, Refshauge KM, Adams J. Health care utilisation and out-of-pocket expenditure associated with back pain: A nationally representative survey of Australian women. PLoS One. 2013;8

Kleiman MB, Francis RG, Moore HA. Chiropractic utilisation in the United States. N Z Med J. 1981;93:43–5.

Kopansky-giles D, Fccs C, Papadopoulos C: a profile of Canadian chiropractors. Practice 1997, 41(C).

Kozma CM, Provenzano D, Slaton T, Patel A, Benson C. Complexity of Pain Management Among Patients with Nociceptive. J Manag Care Pharm. 2014;20:455–66.

Krauss HH, Godfrey C, Kirk J, Eisenberg DM. Alternative health care: its use by individuals with physical disabilities. Arch Phys Med Rehabil. 1998;79(November):1440–7.

Kronenberg F, Cushman LF, Wade CM, Kalmuss D, Chao MT. Race/ethnicity and women’s use of complementary and alternative medicine in the United States: Results of a national survey. Am J Public Health. 2006;96:1236–42.

Lafferty WE, Bellas A, Baden AC, Tyree PT, Standish LJ, Patterson R. The Use of Complementary and Alternative Medical Providers by Insured Cancer Patients in Washington State. Cancer. 2004;100:1522–30.

Leboeuf-Yde C, Grønstvedt A, Borge JA, Lothe J, Magnesen E, Nilsson Ø, Røsok G, Stig L-C, Larsen K. The Nordic Back Pain Subpopulation Program: Demographic and Clinical Predictors for Outcome in Patients Receiving Chiropractic Treatment for Persistent Low–Back Pain. J Manipulative Physiol Ther. 2004;27:493–502.

Leboeuf-Yde C, Pedersen EN, Bryner P, Cosman D, Hayek R, Meeker WC, Shaik JJ, Terrazas O, Tucker J, Walsh M. Self-reported Nonmusculoskeletal Responses to Chiropractic Intervention: A Multination Survey. J Manipulative Physiol Ther. 2005;28:294–302.

Lee A, Li D, Kemper K. Chiropractic care for children. Arch Pediatr adolesc med. 2000;154:401–7.

Lee P, Helewa A, Smythe HA, Bombardier C, Goldsmith CH. Epidemiology of Musculoskeletal Disorders (Complaints) and Related Disability in Canada. J Rheumatol. 1985;12:1169–73.

Legorreta AP: Comparative Analysis of Individuals With and Without Chiropractic Coverage<subtitle>Patient Characteristics, Utilization, and Costs</subtitle>. Arch Intern Med 2004, 164:1985.

Lewis D, Paterson M, Beckerman S, Sandilands C. Attitudes toward integration of complementary and alternative medicine with hospital-based care. J Altern Complement Med. 2001;7:681–8.

Lim A, Cranswick N, Skull S, South M. Survey of complementary and alternative medicine use at a tertiary children’s hospital. J Paediatr Child Heal. 2005;41:424–7.

Lim KL, Jacobs P, Klarenbach S. A population-based analysis of healthcare utilization of persons with back disorders - Results from the Canadian Community Health Survey 2000-2001. Spine (Phila Pa 1976). 2006;31:212–8.

Lind BK, Diehr PK, Grembowski DE, Lafferty WE. Chiropractic use by urban and rural residents with insurance coverage. J Rural Heal. 2009;25:253–8.

Lind B, Lafferty W, Tyree P, Diehr P, Grembowski D. Use of Complementary and Alternative Medicine Providers by Fibromyalgia Patients Under Insurance Coverage. Arthritis Rheum. 2007;57:71–6.

Lind BK, Lafferty WE, Grembowski DE, Diehr PK. Complementary and alternative provider use by insured patients with diabetes in Washington State. J Altern Complement Med. 2006;12:71–7.

Lind BK, Lafferty WE, Tyree PT, Sherman KJ, Deyo RA, Cherkin DC. The role of alternative medical providers for the outpatient treatment of insured patients with back pain. Spine (Phila Pa 1976). 2005;30:1454–9.

Liow K, Ablah E, Nguyen JC, Sadler T, Wolfe D, Tran KD, Guo L, Hoang T. Pattern and frequency of use of complementary and alternative medicine among patients with epilepsy in the midwestern United States. Epilepsy Behav. 2007;10:576–82.

Lishchyna N, Mior S. Demographic and Clinical Characteristics of New Patients Presenting to a Community Teaching Clinic. J Chiropr Educ. 2012;26:161–8.

Loera J, Reyes-Ortiz C, Kuo Y. Predictors of complementary and alternative medicine use among older Mexican Americans. Complement Ther Clin Pract. 2007;13:224–31.

Mackenzie ER, Taylor L, Bloom BS, Hufford DJ, Johnson JC. Ethnic minority use of complementary and alternative medicine (CAM): A national probability survey of CAM users. Altern Ther Health Med. 2003;9:50–6.

MacLennan AH, Myers SP, Taylor AW. The continuing use of complementary and alternative medicine in South Australia: Costs and beliefs in 2004. Med J Aust. 2006;184:27–31.

MacPherson H, Newbronner E, Chamberlain R, Hopton A. Patients’ experiences and expectations of chiropractic care: a national cross-sectional survey. Chiropr Man Therap. 2015;23:3.

Madsen H, Andersen S, Nielsen RG, Dolmer BS, Høst A, Damkier A. Use of complementary/alternative medicine among paediatric patients. Eur J Pediatr. 2003;162:334–41.

Malmqvist S, Leboeuf-Yde C. Chiropractors in Finland - a demographic survey. Chiropr Osteopat. 2008;16:9.

Marchand AM. Chiropractic Care of Children from Birth to Adolescence and Classification of Reported Conditions: An Internet Cross-Sectional Survey of 956 European Chiropractors. J Manipulative Physiol Ther. 2012;35:372–80.

Marrie RA, Hadjimichael O, Vollmer T. Predictors of alternative medicine use by multiple sclerosis patients. Mult Scler. 2003;9:461–6.

Marsh J, Hager C, Havey T, Sprague S, Bhandari M, Bryant D. Use of alternative medicines by patients with oa that adversely interact with commonly prescribed medications. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 2009;467:2705–22.

Martel D, Bussières J-F, Théorêt Y, Lebel D, Kish S, Moghrabi A, Laurier C. Use of alternative and complementary therapies in children with cancer. Pediatr Blood Cancer. 2005;44:660–8.

Martin BI, Gerkovich MM, Deyo RA, Sherman KJ, Cherkin DC, Lind BK, Goertz CM, Lafferty WE. The association of complementary and alternative medicine use and health care expenditures for back and neck problems. Med Care50 (pp 1029-1036), 2012Date Publ December 2012. 2012;50:1029–36.

Martinez DA, Rupert RL, Ndetan HT. A demographic and epidemiological study of a Mexican chiropractic college public clinic. Chiropr Osteopat. 2009;17:4.

McEachrane-Gross FP, Liebschutz JM, Berlowitz D. Use of selected complementary and alternative medicine (CAM) treatments in veterans with cancer or chronic pain: a cross-sectional survey. BMC Complement Altern Med. 2006;6:34.

McHardy AJ, Pollard HP, Luo K. Golf-related lower back injuries: an epidemiological survey. J Chiropr Med. 2007;6:20–6.

Metcalfe A, Williams J, McChesney J, Patten SB, Jetté N. Use of complementary and alternative medicine by those with a chronic disease and the general population--results of a national population based survey. BMC Complement Altern Med. 2010;10:58.

Millar WJ. Use of alternative health care practitioners by Canadians. Can J Public Heal. 1997;88:154–8.

Millar WJ. Patterns of Use - Alternative Health Care Practitioners. Heal Reports/Statistics Canada. 2001;13:9–21.

Miller J. Demographic survey of pediatric patients presenting to a chiropractic teaching clinic. Chiropr Osteopat. 2010;18:33.

Mior SA, Laporte A. Economic and Resource Status of the Chiropractic Profession in Ontario, Canada: A Challenge or an Opportunity. J Manipulative Physiol Ther. 2008;31:104–14.

Montalto CP. Use of Complementary and Alternative Medicine by Older Adults: An Exploratory Study. Complement Health Pract Rev. 2006;11:27–46.

Montgomery M, Huang S, Cox CL, Leisenring WM, Oeffinger KC, Hudson MM, Ginsberg J, Armstrong GT, Robison LL, Ness KK. Physical therapy and chiropractic use among childhood cancer survivors with chronic disease: Impact on health-related quality of life. J Cancer Surviv. 2011;5:73–81.

Mootz RD, Cherkin DC, Odegard CE, Eisenberg DM, Barassi JP, Deyo R a. Characteristics of Chiropractic Practitioners, Patients, and Encounters in Massachusetts and Arizona. J Manipulative Physiol Ther. 2005;28:645–53.

Murthy V, Sibbritt D, Adams J, Broom A, Kirby E, Refshauge KM. Consultations with complementary and alternative medicine practitioners amongst wider care options for back pain: A study of a nationally representative sample of 1,310 Australian women aged 60-65 years. Clin Rheumatol. 2014;33:253–62.

Najm W, Reinsch S, Hoehler F, Tobis J. Use of Complementary and Alternative Medicine among the Ethnic Elderly. Altern Ther Health Med. 2003;9:50–7.

National Center for Complementary and Alternative Medicine National Institutes of Health. American Adult Use of Complementary and Alternative Medicine. J Altern Complement Med. 2005;18:111–4.

Nayak S, Matheis RJ, Agostinellie S, Shiflett SC. The Use of Complementary and Alternative Therapies for Chronic Pain Following Spinal Cord Injury: A Pilot Survey. J Spinal Cord Meicine. 2001;24:54–62.

Nayak S, Matheis RJ, Schoenberger NE, Shiflett SC. Use of unconventional therapies by individuals with multiple sclerosis. Clin Rehabil. 2003;17:181–91.

Ndetan H, Evans MW, Bae S, Felini M, Rupert R, Singh KP. The health care provider’s role and patient compliance to health promotion advice from the user’s perspective: Analysis of the 2006 national health interview survey data. J Manipulative Physiol Ther. 2010;33:413–8.

Newton KM, Buist DS, Keenan NL, Anderson L a, Lacroix a Z. Use of Alternative Therapies for Menopause Symptoms: Results of a Population-Based Survey. [Article]. Obstet Gynecol. 2002;100:18–25.

Nichols AW, Harrigan R. Complementary and Alternative Medicine Usage by Intercollegiate Athletes. Clin J Sport Med. 2006;16:232–7.

Nyiendo J, Haldeman S. A prospective study of 2,000 patients attending a chiropractic college teaching clinic. Med Care. 1987;25:516–27.

Nyiendo J, Phillips R, Meeker W, Konsler G, Jansen R, Menon M. A Comparison of Patients and Patient Complaints at Six Chiropractic College Teaching Clinics. J Manipulative Physiol Ther. 1989;12:79–85.

Nyiendo J, Haas M, Goldberg B, Sexton G. Patient characteristics and physicians’ practice activities for patients with chronic low back pain: A practice-based study of primary care and chiropractic physicians. J Manipulative Physiol Ther. 2001;24:92–100.

Nyiendo J, Olsen E. Visit Characteristics of 217 Children Attending a Chiroprctic College Teaching Clinic. J Manipulative Physiol Ther. 1988;11:78–84.

Opheim R, Bernklev T, Fagermoen MS, Cvancarova M, Moum B. Use of complementary and alternative medicine in patients with inflammatory bowel disease: results of a cross-sectional study in Norway. Scand J Gastroenterol. 2012;47:1436–47.

Paramore LC: Use of alternative therapies: Estimates from the 1994 Robert Wood Johnson Foundation National Access to Care Survey. J Pain Symptom Manage 1997, 13:83–89.

Pedersen P, Kleberg PK, Walker K. A pilot survey of patients and chiropractors in European chiropractic practices: sociodemographic, anamnestic and management procedures. Eur J Chiropr. 1993;41:5–19.

Pedersen P. A survey of chiropractic practice in Europe. Eur J Chiropr. 1994;42:3–28.

Pedersen P, Breen AC. An Overview of European Chiropractic Practice. J Manipulative Physiol Ther. 1994;17:228–37.

Phillips RB, Mootz RD, Nyiendo J, Cooperstein R, Konsler J, Mennon M. The Descriptive Profile of Low Back Pain Patients of Field Practicing Chiropractors Contrasted with Those Treated in the Clinics of West Coast Chiropractic Colleges. J Manipulative Physiol Ther. 1992;15:512–7.

Piérard E. Substitutes or complements? An exploration of the effect of wait times and availability of conventional care on the use of alternative health therapies in Canada. Complement Ther Med. 2012;20:323–33.

Pledger MJ, Cumming J, Burnette M. THE NEW ZEALAND MEDICAL JOURNAL Health service use amongst users of complementary and alternative medicine. J New Zeal Med Assoc NZMJ. 2010;123:26–35.

Post-White J, Fitzgerald M, Hageness S, Sencer SF. Complementary and Alternative Medicine Use in Children With Cancer and General and Specialty Pediatrics. J Pediatr Oncol Nurs. 2008;26:7–15.

Poulsen E, Christensen HW, Overgaard S, Hartvigsen J. Prevalence of hip osteoarthritis in chiropractic practice in Denmark: A descriptive cross-sectional and prospective study. J Manipulative Physiol Ther. 2012;35:263–71.

Quan H, Lai D, Johnson D, Verhoef M, Musto R. Complementary and alternative medicine use among Chinese and white Canadians. Can Fam Physician. 2008;54:1563–9.

Reinhard MJ, Nassif TH, Bloeser K, Dursa EK, Barth SK, Benetato B. CAM Utilization Among OEF / OIF Veterans of US Veterans. Med Care. 2014;52:45–9.

Rivera JO, Ortiz M, Lawson ME, Verma KM. Evaluation of the Use of Complementary and Alternative Medicine in the Largest United States-Mexico Border City. Pharmacotherapy. 2002;22:256–64.

Robinson A, Chesters J, Cooper S. Beyond a Generic Complementary and Alternative Medicine: The Holistic Health Care-Conventional Medicine Continuum. Complement Health Pract Rev. 2009;14:153–63.

Robinson A, Chesters J, Cooper S. People’s choice: complementary and alternative medicine modalities. Complement Health Pract Rev. 2007;12:99–119.

Rosen JE, Gardiner P, Saper RB, Filippelli AC, White LF, Pearce EN, Gupta-Lawrence RL, Lee SL. Complementary and alternative medicine use among patients with thyroid cancer. Thyroid. 2013;23:1238–46.

Rosenfeld L. Chiropractic Versus Nonchiropractic Patients in North Carolina: A Comparison of Demographic Characteristics and Perceptions of Health Care Providers. Dig Chiropr Econ. 1987:22–5.

Ross LE, Fletcher A, Anderson MC, Meade SA, Powe BD, Howard D. Complementary and alternative medicine (CAM) use among men with a history of prostate cancer. J Cult Divers. 2012;19:143–50.

Rubinstein S, Pfeifle CE, Van Tulder MW, Assendelft WJJ. Chiropractic patients in the Netherlands: A descriptive study. J Manipulative Physiol Ther. 2000;23:557–63.

Ryder PT, Wolpert B, Orwig D, Carter-Pokras O, Black SA. Complementary and Alternative Medicine Use among Older Urban African Americans: Individual and Neighborhood Associations. J Natl Med Assoc. 2008;100(Oct):1186–92.

Sandnes KF, Bjørnstad C, Leboeuf-Yde C, Hestbaek L. The Nordic maintenance care program--time intervals between treatments of patients with low back pain: how close and who decides? Chiropr Osteopat. 2010;18:5.

Sarris J, Robins Wahlin T-B, Goncalves DC, Byrne GJ. Comparative use of complementary medicine, allied health, and manual therapies by middle-aged and older Australian women. J Women Aging. 2010;22:273–82.

Sawni-Sikand A, Schubiner H, Thomas RL. Use of Complementary/Alternative Therapies Among Children in Primary Care Pediatrics. Ambul Pediatr. 2002;2:99–103.

Sawyer C, Stewart L. Demographic, Clinical, and Utilization Characteristics of Chiropractic Teaching Clinic Patients: Implications for Clinical and Epidemiological Investigation. ACA J Chiropr. 1984;18:59–66.

Sawyer C, Ramlow J. Attitudes of Chiropractic Patients: A Preliminary Survey of Patients Receiving Care in a Chiropractic Teaching Clinic. J Manipulative Physiol Ther. 1984;7:157–63.

Saxe G A, Madlensky L, Kealey S, Wu DPH, Freeman KL, Pierce JP: Disclosure to physicians of CAM use by breast cancer patients: findings from the Women’s Healthy Eating and Living Study. Integr Cancer Ther 2008, 7:122–129.

Schwarz S, Messerschmidt H, Völzke H, Hoffmann W, Lucht M, Dören M. Use of complementary medicinal therapies in West Pomerania: a population-based study. Climacteric. 2008;11(June):124–34.

Scott JA, Kearney N, Hummerston S, Molassiotis A. Use of complementary and alternative medicine in patients with cancer: A UK survey. Eur J Oncol Nurs. 2005;9:131–7.

Shah SH, Engelhardt R, Ovbiagele B. Patterns of complementary and alternative medicine use among United States stroke survivors. J Neurol Sci. 2008;271:180–5.

Shakeel M, Newton J, Wong Ah-See K. Complementary and Alternative Medicine Use among Patients Undergoing Otolaryngologic Surgery. J Otolaryngol. 2009;38:355–61.

Shakeel M, Trinidade A, Ah-See KW. Complementary and alternative medicine use by otolaryngology patients: A paradigm for practitioners in all surgical specialties. Eur Arch Oto-Rhino-Laryngology. 2010;267:961–71.

Sharma R, Haas M, Stano M. Patient Attitudes, Insurance, and Other Determinants of Self-Referral to Medical and Chiropractic Physicians. Am J Public Health. 2003;93:2111–7.

Shekelle PG, Brook RH. A community-based study of the use of chiropractic services. Am J Public Health. 1991;81:439–42.

Sherman KJ, Cherkin DC, Connelly MT, Erro J, Savetsky JB, Davis RB, Eisenberg DM. Complementary and alternative medical therapies for chronic low back pain: What treatments are patients willing to try? BMC Complement Altern Med. 2004;4:9.

Sherwood P. Patterns of use of complementary medicines in health services in the south-west of Western Australia. Aust J Rural Heal. 2000;8:194–200.

Simon GE, Cherkin DC, Sherman KJ, Eisenberg DM, Deyo RA, Davis RB. Mental health visits to complementary and alternative medicine providers. Gen Hosp Psychiatry. 2004;26:171–7.