Abstract

Background

The most utilized soccer kicking method is the instep kicking technique. Decreased motion in spinal joint segments results in adverse biomechanical changes within in the kinematic chain. These changes may be linked to a negative impact on soccer performance. This study tested the immediate effect of lumbar spine and sacroiliac manipulation alone and in combination on the kicking speed of uninjured soccer players.

Methods

This 2010 prospective, pre-post experimental, single-blinded (subject) required forty asymptomatic soccer players, from regional premier league teams, who were purposively allocated to one of four groups (based on the evaluation of the players by two blinded motion palpators). Segment dysfunction was either localized to the lumbar spine (Group 1), sacroiliac joint (Group 2), the lumbar spine and sacroiliac joint (Group 3) or not present in the sham laser group (Group 4). All players underwent a standardized warm-up before the pre-measurements. Manipulative intervention followed after which post-measurements were completed. Measurement outcomes included range of motion changes (digital inclinometer); kicking speed (Speed Trac™ Speed Sport Radar) and the subjects’ perception of a change in kicking speed. SPSS version 15.0 was used to analyse the data, with repeated measures ANOVA and a p-value <0.05 (CI 95%).

Results

Lumbar spine manipulation resulted in significant range of motion increases in left and right rotation. Sacroiliac manipulation resulted in no significant changes in the lumbar range of motion. Combination manipulative interventions resulted in significant range of motion increases in lumbar extension, right rotation and right SI joint flexion. There was a significant increase in kicking speed post intervention for all three manipulative intervention groups (when compared to sham). A significant correlation was seen between Likert based-scale subjects’ perception of change in kicking speed post intervention and the objective results obtained.

Conclusions

This pilot study showed that lumbar spine manipulation combined with SI joint manipulation, resulted in an effective intervention for short-term increases in kicking speed/performance. However, the lack of an a priori analysis, a larger sample size and an unblinded outcome measures assessor requires that this study be repeated, addressing these concerns and for these outcomes to be validated.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

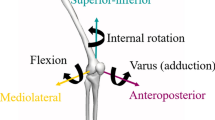

The instep kicking technique is the most commonly used kicking technique in soccer, which allows the development of an optimum kicking speed [1-3]. This kicking technique requires that the power is generated through the co-ordinated effort of the muscles and the motion of all the joints involved (viz. lumbar spine, sacroiliac joint, hip, knee and foot and ankle) [4,5]. Thus, this kicking technique’s biomechanics are seen as a segmented motion pattern sequence which initiates from the at the spine and moves distally down the open biomechanical chain [4-7]. As, the lumbar spine and sacroiliac joint are both proximal parts of this biomechanical chain, they form the basis for motion which follows the open chain movement pattern, and thus initiate the forward motion during kicking [2,5]. Thus musculoskeletal co-ordination forms the basis for the kicking action and closely controls the compression forces being transferred towards the spine, stabilising and keeping the upper body balanced and upright, whilst transmitting the requires forces down the kinematic chain [8].

To achieve the above, the player’s approach or backswing phase of the kicking technique requires that the lumbar spine rotates posteriorly and extends allowing the trunk to rotate towards the kicking leg [2,9,10]. At the end of the swing limb loading phase the lumbar spine is rotated and extended, in accordance with soccer technique, in order to appropriately load the thoraco-lumbar fascia for recoil and wind up prior to the kick. This increase in musculo-ligamentous torque during in the wind up, allows for maximum distance to be achieved when striking the ball. Once, the swing phase is initiated by the trunk, the lumbar spine rotates towards the supporting leg to transfer momentum from the larger proximal segments to the distal smaller ones, in order to accelerate the kicking limb into flexion at the hip [2,9,10], as it speeds towards the ball.

At this point Cohan [11] and Gilchrist et al., [8], concur that the hip and sacroiliac musculature are required to work together to effect movement of the pelvis (for example hip joint extension causes anterior pelvic tilt and extending the SI joint). Similarly, hip flexion is associated with posterior pelvic tilt and allows the SI joint to assume a flexed position [2]. By contrast, during the foot planting phase, the SI joint is active in absorbing and controlling the force being transmitted through the body and down the biomechanical chain, as a result of the ground reactive force acting on the limb [2].

It is therefore evident that the instep soccer kick is a complex maneuver, on which the outcome of a soccer game depends [12,13]. Thus, players are expected to perform this “routine action” at their maximum potential every time they kick the ball to score. This co-ordination of this components of this complex maneuver impacts on the kicking speed [direct result of a summation of forces created by the musculoskeletal basis of the kick and its generated momentum down the biomechanical chain] [2,4,5,8]. In addition, an increase in the distance over which the open kinematic chain can move, it is hypothesized that there will be an increase in the potential to achieve a higher foot speed at the point of impact [2,9,10,14].

This hypothesis concurs with the literature, which indicates that when immobilization or restricted motion exists within any of these joint segments, it results in adverse changes in the surrounding ligaments, tendons, muscular tissue and vascular elements [15-17]. It is through these functional impairments with a loss of tensile strength of ligaments, adhesions formation [15,16,18,19], loss of muscular or ligamentous flexibility and joint range of motion (ROM) decreases [17,19-22], that performance may be decreased . Therefore it is the opinion of several authors that improved spinal joint mobility and muscle flexibility can be achieved through the use of manipulation [15,16,22-25].

Thus the restoration of normal biomechanics and neurological input [26-29], increased flexibility and mobility of joints and surrounding tissues resulting from manipulation [23,30,31] may result in increased speed of the biomechanical chain during the kicking motion.

There is however, limited published literature on the immediate post manipulation effect of manipulation on the ROM of the low back joints in asymptomatic subjects. Therefore, this study determined whether manipulation of the lumbar spine and the sacroiliac joints increased the ROM at within these anatomical regions (measured goniometrically) and whether this was associated with changes in kicking speed and the subjective perception of the kicking ability.

Method

Recruitment and informed consent

On Institutional Research and Ethics Committee of the Durban University of Technology (034/10) approval of this study in 2010, the subjects were recruited after permission was received from the Highway Action Center. Players were informed of the study by the placement of advertisements at the arena and through word of mouth. In addition players in the regional premier league teams were approached by the researcher in order to request participation (convenience sampling) [32]. Subsequent interaction with the potential subjects required that the soccer players read and understood the letter of information and informed consent as approved by the IRB and agreed to participate by voluntarily signing the informed consent.

On agreement to participate the subjects were then required to undergo a clinical assessment (case history, physical and orthopedic examinations), which was administered at the Chiropractic Day Clinic, to ensure that the subjects complied with the inclusion criteria.

Sample size and allocation

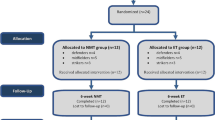

A sample size of 40, asymptomatic subjects was required for this study, resulting in ten subjects in each of four intervention groups. Due to the lack of access to national league teams, the researcher was limited to regional premier league teams. This resulted in a relatively small sample pool (approximately 75 soccer players) from which to draw subjects for this study. As a result the sample size was based on a pragmatic decision rather than a statistical evaluation of sample size (viz. a prior analysis).

The subjects were purposively assigned to one of four intervention groups, based on the level of the motion segment dysfunction. This was based on a standardised motion palpation protocol developed from Bergmann and Peterson [21], Schafer and Faye [33] and Bergmann, Peterson and Lawrence [34], of the lumbar spine and sacroiliac joints. This procedure was performed independently by both the researcher and the clinical supervisor [35]. The subjects were allocated to their respective group - lumbar spine (Group 1), sacroiliac joint (Group 2), the lumbar spine and sacroiliac joint (Group 3) - by those joint dysfunctions that were commonly agreed to by the researcher and the clinical supervisor. Those subjects with no joint dysfunction in the palpated joints were placed into Group 4.

Sample characteristics

Subjects were required to be males, between the ages of 18 to 35 and had to be soccer athletes (no distinction was made with regard to player position), as all players must be able to kick and due to the small numbers that were available. Subjects were required to have clinical signs of joint dysfunction (asymptomatic, e.g. pain) [21,34] in either the lumbar spine or the sacroiliac joints or both. Exclusion criteria included subjects who presented with contraindications to spinal manipulations [21,34].

Procedure

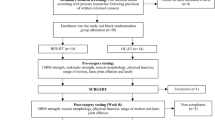

After subjects signed informed consent, inclusion into the study (at the initial consultation) and allocation to a group (at the data collection arena/subsequent consultation) was determined. All players were instructed through a standardized warm-up procedure prior to measurements being taken. Each player was taken through a standardized procedure required which included a warm up run around the outside of an indoor court, a seated self stretch of the hamstrings, a prone self stretch for the quadriceps femoris, a seated stretch for the adductor muscles, a supine stretch for the quadratus lumborum and a standing gastrocnemius and soleus [36].

After the completion of the warm up procedure the pre-intervention measurements were taken: lumbar (flexion, extension, lateral flexion, and rotation) and sacroiliac (flexion and extension) range of motion parameters. The player was then required to complete a maximum run-up distance of 3 meters (the angle of the run-up was not specified so as to not interrupt the subjects natural kicking technique [6]); whilst completing an instep kick performed at maximum power. All three kicks were required to be taken with the preferred foot only.

This was then followed by the group-appropriate intervention:

-

For lumbar SI, the lumbar roll technique was used as described by Szaraz [37].

-

For the sacroiliac manipulation, a side lying technique was used with pisiform, posterior superior iliac spine contact as described by Bergmann, Peterson, and Lawrence [34].

-

A combination of the above for the combination group.

-

Laser intervention for the sham group.

Manipulation of a dysfunctional joint was considered successful if on reassessment after the manipulation, the motion palpation of that joint [33,34] showed improvement post manipulation and there was agreement between the researcher and the clinical supervisor (blinded to manipulation).

After the intervention the post-intervention measures were administered immediately (in order of lumbar and sacroiliac range of motion, repeated kicking outcomes and the subjective perception of the kick (improved, the same or worse)).

Outcome measures

The range of motion was measured using a Saunders digital inclinometer [38]. Mayer, Kondraske, Beals and Gatchel [39], found that there was minimal error when using an inclinometer, however where error might be seen is on the examiners ability to locate bony anatomical landmarks (which was overcome in this study by marking the appropriate landmarks).

Lumbar range of motion: flexion, extension, lateral flexion and rotation motion was assessed according to the outlines provided in the manual by the Saunders Group [38] and Mayer, Kondraske, Beals and Gatchel [39].

Sacroiliac Range of Motion (only flexion motion was assessed), was assessed as outlined by Schafer and Faye [33], Bergmann, Peterson and Lawrence [34] and Saunders [38]. Calculations were done according to Arab et al., [40].

Performance was measured using the SpeedTrac™ Speed Sport Radar, which measured the kicking speed of the subjects. This device (EMG Companies, Wisconsin, USA) utilized Doppler signal processing to measure speeds of small projectiles. An internal antenna sends out radio waves at a specific frequency, so when a moving object, such as a kicked ball, enters the range of this signal it alters the frequency. The frequency of the reflected signal off the ball changes the frequency in proportion to the ball’s speed. The radar then displays the speed in the units of choice, in this case km/h. The signal transmitted is able to pass through netting without being affected. Therefore, a protective barrier can be placed between the moving object and the radar without affecting the accuracy of the measurements in any way. The speed range of the radar is 10-199 km/h, and the distance range is approximately nine meters. The accuracy of the radar is within 2-3 km/h [EMG Companies, Wisconsin, USA]. The SpeedTrac™ Speed Sport Radar was set up (specifically for this study), in the indoor arena behind the netting of the goal, so as to protect the unit; give the most accurate readings (7.5 meters away from the kicking point) and to give the subjects a target to assist aim.

In terms of the subjective outcomes of the study, subjects were all required to answer the following question post intervention, “Did you feel that your kicking speed increased or decreased or remained the same following the treatment?” (3 point Likert Scale).

Statistics

SPSS version 15.0 was used to analyse the data. A p value < 0.05 indicated statistical significance. Demographic characteristics were compared between the groups using ANOVA tests. Intra-group comparisons of outcomes over time were achieved using within-subjects repeated measures ANOVA. A significant time effect indicated a significant effect of the intervention where each subject was used as their own control. Intra and inter-group comparison of interventions was achieved using between and within groups repeated measures ANOVA. A significant time verses group effect indicated that the interventions produced different results over time. Comparison of subjective and objective change in kicking speed was assessed using cross tabulations and Pearson’s chi square tests [41]. Normalcy of data were computed utilizing the Kolmogorov’s Smirnov test and normal probability plots.

Results

Figure 1 outlines the flow of subjects through the study, based on the procedure outlined in the methodology. In terms of the baseline (pre-intervention) measurements between the groups there was no significant differences in terms of the subjects age, height and weight (demographic data) (Table 1).

In terms of the pre-post intervention measures (using the Wilks Lambda tests), statistically significant increases in right and left lumbar spine rotation ranges of motion (Group 1) and lumbar spine extension, right and left lumbar spine rotation and sacroiliac joint flexion range of motion (Group3) were reflected. No significant changes were seen with Group 2 and Group 4 (Table 2).

In the intergroup comparisons Table 3 reflects the outcomes between the groups. This Table agrees with the outcomes of Table 2, where the significant differences seen pre-post for the individual groups are also the same reasons for the significant differences between the groups. Additionally all three manipulative Groups showed statistically significant increases in kicking speeds (Table 4) with the sham laser intervention no effect post intervention for kicking speed. Further, a significant relationship between perception of improved performance and the improvement in kicking speed was noted (Table 5 (average kicking speed)/Table 6 (maximum kicking speed)), but there was no correlation between in the improved kicking speed and range of motion of either the lumbar spine or the sacroiliac joints.

Discussion

Due to the fact that in all four Groups the subjects were aware that they were being studied, it was considered that the full effects of the Hawthorne principles were negated as each group would have had a similar exposure to these effects and thus they would have been negated in the inter-group comparisons [32,42].

In light of the above, the results seem to suggest that, manipulation of the lumbar spine alone or in conjunction with the sacroiliac joint, seems to result in the most significant results in soccer players, with regards to kicking speed. This outcome may be attributed to the nature of the lumbar spine manipulation (rotation) used, coupled with slight extension [29], which lends itself to the recorded results where the only statistically significant differences were noted in the rotation and extension motions during inter-group comparisons (Table 2).

Additionally, the lumbar spine and sacroiliac joint combination manipulation group achieved the highest rate of improvement followed by the sacroiliac joint manipulation and then lumbar spine manipulation groups. This outcome concurs with the results obtained by Sood [43], where it was found that combination groups (thoracic and lumbar manipulation) resulted in the greatest degree of improvement and significant (p < 0.000) improvement for action cricket fast bowlers’ bowling speed. This is however in contrast to the findings of Le Roux [44] in amateur golfers where no significant improvements were seen in participants that received combination manipulation interventions. The difference may lie in the fact that Sood [43] and this study utilized athletes specialized roles as opposed to the amateur athletes in the study by Le Roux [44]. This is supported by Gowan et al. [45], Shrier et al. [46] and Lauro and Mouch [47].

It may however also need to be considered that athletes respond differently to manipulation when combined with another modality, as found in the study by Costa et al. [48], where a combination of manipulation and stretching improved the overall outcome for the athletes. This concept of muscle stretch may have adversely affected the outcomes of this study as athletes were placed in the lumbar roll position for the sacro-iliac and lumbar spine manipulation procedures and not for the sham laser intervention. This would have predisposed the intervention groups to muscle stimulation that may not have been present in the sham laser intervention group. Further, different responses to manipulation may be sport specific, position specific or perception specific in terms of the athlete, but may also be related to the definition of the musculoskeletal dysfunction and the intervention combinations/chiropractic care utilized [49], as well as the known neurophysiological effects of manipulation [50].

In this study, the performance results can only be due to the fact that athletes responded biomechanically (only range of motion was measured) to manipulation due to the effect of the manipulation on the joints and surrounding anatomical structures [26]. These outcomes therefore support and suggest that the biomechanical [2] role of the lumbar spine and sacroiliac joint manipulation does affect the instep kicking technique, through mechanisms suggested by Herzog, [23] and Pickar, [26]. Additionally, this concurs with results found in sports related research [30,51,52], indicating that increased movement of the biomechanical chain could increase the ball speed following foot-ball impact. Studies show that manipulative interventions (with controlled external conditions) resulted in players acquiring appropriate balance [2] between the musculoskeletal structures [20] leading to the improvements in performance.

Although the neurological effect of the manipulation was not measured in this study, it may have played a role in attaining the positive outcomes (increased kicking performance and increased range of motion). This possibility is supported by Pickar [26], Murphy [27]; Herzog [28], Symons [29] and Suter et al. [30], whose collective literature suggests that the outcome of a complex motion is most likely related to improved neurological co-ordination. This would suggest that an increased limb swinging speed and thus resultant kicking speed would result in improved performance.

The majority of the subjects’ perception was that the kicking speed had increased following the intervention. The perception of increase was matched with 96% of the subjects actually increasing the average kicking speeds and 92% increasing the maximum kicking speeds post intervention. There was, therefore, a statistically significant association between changes in kicking speeds immediately post intervention and the subjects’ perception of change in kicking speed.

Limitations

One of the major limitations in this study was that of sample size.

Future research

Future research needs to measure the neurological effect of manipulation and its impact in all forms of sport, but particularly soccer players to substantiate the outcomes of this study. Outcomes measures should include of measures neurological function, as it has been shown that manipulation results in neurological change in the cervical spine [52,53], which may also impact on biomechanical outcomes achieved.

Further research could also explore the effects of ipsilateral and contra lateral manipulation of the lumbar spine in combination with sacroiliac joint manipulation and how this would alter outcomes on kicking speed. Also, research on the effect of manipulation of the joints both lower down and higher up the kinematic chain be considered – either in isolation or in combination. Both of the above studies would benefit from utilizing professional players that have position specific training, which may increase the ability to detect smaller variances in range of motion and other outcome measures, as their kicking performance would be more consistent.

Conclusions

This pilot study has demonstrated that lumbar spine and SI joint manipulation, when combined are an effective intervention for a short-term increase in kicking speed after one intervention. These outcomes are however only generalizable to those subjects that had improved motion of the dysfunctional motion segment on motion palpation after manipulation. Additionally, the use of a larger sample calculated on an a priori analysis would assist in validating the outcomes of this study and reduce the risk of type II error. This along with improved measures, obtained by utilizing a blinded assessor for the outcome measures; increase frequency of the intervention may assist in conclusively supporting or refuting the results obtained in this study.

References

Ingley B, Harris B. Soccer kick biomechanics [online]. Available at: http://www.ultimatesoccercoaching.com/soccer-kick/soccer-kick-biomechanics.html. 2001. Accessed 18 November 2009.

Kellis E, Katis A. Biomechanical characteristics and determinants of instep soccer kick. J Sports Sci Med. 2007;6:154–65.

Nunome H, Georgakis A, Shinkai H, Suito H, Tsujimoto N and Ikegami Y. Impact phase kinematics of side-foot and instep soccer kick. J Biomech 2007;40(S2).

Lees A. Biomechanics applied to soccer skills. In: Reilly T, editor. Science and soccer. London: E and FN Spon; 1996.

Lees A, Nolan L. The biomechanics of soccer: a review. J Sports Sci. 1998;16:211–34.

Dørge H, Bull Andeersen T, Sørensen H, Simonsen T. Biomechanical differences in soccer kicking with the preferred and the non-preferred leg. J Sports Sci. 2002;20:293–9.

Luhtanen P. Kinematics and kinetics of maximal instep kicking in junior soccer players. In: Reilly T, Lees A, Davids K, Murphy W, editors. Science and football. London: E and FN Spon; 1998.

Gilchrist R, Frey M, Nadler S. Muscular control of the lumbar spine. Pain Physician. 2003;6:361–8.

Barfield W, Kirkendall D, Yu B. Kinematic instep kicking differences between elite female and male soccer players. J Sports Sci Med. 2002;1:72–9.

Ishmail A, Mansor M, Ali M, Jaafar S, Johar M. Biomechanics analysis for right leg instep kick. J Appl Sci. 2010;10(13):1286–92.

Cohan S. Sacroiliac joint pain: a comprehensive review of anatomy, diagnosis, and treatment. Anaesth Analg. 2005;101:1440–53.

Sterzing T, Henning E. The influence of friction properties of shoe upper materials on kicking velocity in soccer. J Biomech. 2007;40(2):195.

Bir C, Cassatta J, Janda D. An analysis and comparison of soccer shin guards. Clin J Sports Med. 1995;5(2):95–9.

Young W, Clothier P, Otago L, Bruce L, Liddell D. Acute effects of static stretching on hip flexor and quadriceps flexibility, range of motion and foot speed in kicking a football. J Sci Med Sport. 2004;7(1):23–31.

Cramer GD, Tuck NR, Knudsen JT, Fonda SD, Schliesser JS, Fournier JT, et al. Effects of side posture positioning and side posture adjusting on the lumbar zygopophyseal joints as evaluated by magnetic resonance imaging: a before and after study with randomisation. J Manipulative Physiol Ther. 2000;23:380–94.

Cramer CG, Gregerson DM, Knudsen JT, Hubbard BB, Ustas JA, Cantu JA. The effects of side posture positioning and spinal adjusting on the lumbar Z joints: a randomised controlled trial with sixty four subjects. Spine. 2002;27(22):2459–66.

Mooney V, Robertson J. The facet syndrome. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 1976;115:149–56.

Paris S. Anatomy as related to function and pain. symposium on evaluation and care of lumbar spine problems. Orthop Clin North Am. 1983;14:476–89.

Jortikka MO, Inkinen RI, Tammi MI, Parkkinen JJ, Haapala J, Kiviranta I, et al. Immobilisation causes longlasting matrix changes both in the immobilised and contralateral joint cartilage. Ann Rheum Dis Suppl. 1997;56(4):255–61.

Appell HJ. Muscular trophy following immobilisation. A review. Sports Med. 1990;10(1):42–58.

Redwood D. Spinal adjustment for low back pain. Semin Integr Med. 2003;1(1):42–52.

Bergmann TF, Peterson DH. Chiropractic technique: 3rd ed. St. Louis, Missouri, United States of America: Elsevier Health Science; 2010.

Herzog W. The mechanical, neuromuscular and physiologic effects produced by the spinal manipulation. In: Herzog W, editor. Clinical biomechanics of spinal manipulation. New York: Churchill Livingstone; 2000.

Gatterman MI, Cooperstein R, Lantz C, Perle SM, Schneider MJ. Rating specific chiropractic technique procedures for common low back conditions. J Manipulative Physiol Ther. 2001;24(7):449–56.

Ianuzzi A, Khalsa PS. Comparison of human lumbar facet joint capsule strains during simulated high velocity, low amplitude spinal manipulation versus physiological motions. Spine J. 2005;5:277–90.

Pickar J. Neurophysiological effects of spinal manipulation. Spinal J. 2002;2(5):357–71.

Murphy BA, Dawson NJ, Slack JR. Sacroiliac joint manipulation decreases the h-reflex. Electroencephalogr Clin Neuro Physiol. 1995;35:87–94.

Herzog W, Scheele D, Conway PJ. Electromyographic responses of back and limb muscles associated with spinal manipulative therapy. Spine. 1999;24:146–53.

Symons BP, Herzog W, Leonard T, Nguyen H. Reflex responses associated with activator treatment. J Manipulative Physiol Ther. 2000;23:155–9.

Suter E, McMorland G, Herzog W, Bray R. Conservative lower back treatment reduces inhibition in knee-extensor muscles: a randomized controlled trial. J Manipulative Physiol Ther. 2000;25(2):76–80.

Fox M. Effect on hamstring flexibility of hamstring stretching compared to hamstring stretching and sacroiliac joint manipulation. Clin Chiropractic. 2006;9:21–32.

Mouton J. Understanding social research. 3rd ed. Pretoria: Van Shaik Publishers; 1996.

Schafer R, Faye J. Motion palpation and chiropractic technique. 2nd ed. Huntington Beach, California, United States of America: The Motion Palpation Institute; 1990.

Bergmann T, Peterson D, Lawrence D. Chiropractic Technique. New York, New York, United States of America: Churchill Livingstone Inc; 1993.

Marcotte J, Normand MC, Black P. Kinematics of motion palpation and its effect on the reliability for cervical spine rotation. J Manipulative Physiol Ther. 2002;25(7):E7.

Travell JG, Simons DG. Myofascial pain and dysfunction: the trigger point manual. Baltimore: Williams and Wilkins; 1983.

Szaraz ZT. Compendium of chiropractic technique. 2nd ed. Toronto: Vivian L.R. Associates Ltd. Technical Publications; 1990.

Saunders H. Saunders digital inclinometer users guide. 4250 Norex Dr, Chaska, Minnesota, 55318-3047: The Saunders Group, Inc; 1998.

Mayer TG, Kondraske G, Beals SB, Gatchel RJ. Spinal range of motion. Accuracy and sources of error with inclinometric measurement. Spine. 1997;22(17):1976–84.

Arab A, Abdollahi I, Joghataei M, Golafshani Z, Kazemnejad A. Inter- and intra-examiner reliability of single and composites of selected motion palpation and pain provocation tests for sacroiliac joint. Man Ther. 2009;14:213–21.

Esterhuizen T. (Private communications), 16 August 2010, 14:06 PM.

McCarney R, Warner J, Iliffe S, Van Haselen R, Griffin M, Fisher P. The hawthorne effect: a randomised, controlled trial. BMC Med Res Methodol. 2007;7:30.

Sood K. The immediate effect of lumbar spine manipulation, thoracic spine manipulation, combination lumbar and thoracic spine manipulation and sham laser on bowling speed in action cricket fast bowlers. Durban: Master’s Degree in Chiropractic, Durban University of Technology; 2008.

Le Roux S. The immediate and short term effect of spinal manipulative therapy (SMT) on asymptomatic amateur golfers in terms of performance indicators. Durban: Master’s Degree in Chiropractic, Durban University of Technology; 2008.

Gowan ID, Jobe FW, Tibone JE, Perry J, Moynes DR. A comparative electromyographic analysis of the shoulder during pitching: professional versus amateur pitchers. Am J Sports Med. 1987;15(6):586–90.

Shrier I, MacDonald D, Uchacz G. A pilot study on the effects of pre-event manipulation on jump height and running velocity. Br J Sports Med. 2006;40:947–9.

Lauro A, Mouch B. Chiropractic effects on athletic ability. J Chiropractic Res Invest. 1991;6(4):84–7.

Costa SMV, Chibana YET, Giavarotti L, Compagnoni DS, Shiono AH, Satie J, et al. Effect of spinal manipulative therapy with stretching compared with stretching alone on full-swing performance of golf players: a randomised pilot trial. J Chiropractic Med. 2009;8:165–70.

Greenstein JS. Chiropractic enhancement of sports performance. Adv Chiropractic. 1997;4:295–320.

Leach R. The chiropractic theories: a textbook of scientific research. 4th ed. Philadelphia, Pennsylvania: Lippincott Williams and Wilkins. ISBN 978-0683307474

Bicalho E, Setti J, Macagnan J, Cano J, Manffra E. Immediate effects of a high-velocity spine manipulation in paraspinal muscles activity of nonspecific chronic low-back pain subjects. Man Ther. 2010;15:469–75.

Botelho MB, Andrade BB. Effect of cervical spine manipulative therapy on judo athletes’ grip strength. J Manipulative Physiol Ther. 2012;35(1):38–44.

Cramer G, Brudgell B, Henderson C, Khalsa P, Pickar J. Basic science research related to chiropractic spinal adjusting: the state of the art and recommendations revisited. J Manipulative Physiol Ther. 2006;29(9):726–60.

Funding

The study was funded through a grant from the Durban University of Technology.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Authors’ contributions

KCD principle researcher, who obtained his Master in Technology of Chiropractic degree. ADJ supervisor of the masters study. CMK presenter of study at Federation Internationale de Chiropractique du Sport symposium as well as manuscript preparation, co-ordination and update. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Rights and permissions

This article is published under an open access license. Please check the 'Copyright Information' section either on this page or in the PDF for details of this license and what re-use is permitted. If your intended use exceeds what is permitted by the license or if you are unable to locate the licence and re-use information, please contact the Rights and Permissions team.

About this article

Cite this article

Deutschmann, K.C., Jones, A.D. & Korporaal, C.M. A non-randomised experimental feasibility study into the immediate effect of three different spinal manipulative protocols on kicking speed performance in soccer players. Chiropr Man Therap 23, 1 (2015). https://doi.org/10.1186/s12998-014-0046-3

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s12998-014-0046-3