Abstract

Background

Exclusive breastfeeding (EBF) improves infant health and survival. We tested the effectiveness of a home-based intervention using Community Health Workers (CHWs) on EBF for six months in urban poor settings in Kenya.

Methods

We conducted a cluster-randomized controlled trial in Korogocho and Viwandani slums in Nairobi. We recruited pregnant women and followed them until the infant’s first birthday. Fourteen community clusters were randomized to intervention or control arm. The intervention arm received home-based nutritional counselling during scheduled visits by CHWs trained to provide specific maternal infant and young child nutrition (MIYCN) messages and standard care. The control arm was visited by CHWs who were not trained in MIYCN and they provided standard care (which included aspects of ante-natal and post-natal care, family planning, water, sanitation and hygiene, delivery with skilled attendance, immunization and community nutrition). CHWs in both groups distributed similar information materials on MIYCN. Differences in EBF by intervention status were tested using chi square and logistic regression, employing intention-to-treat analysis.

Results

A total of 1110 mother-child pairs were involved, about half in each arm. At baseline, demographic and socioeconomic factors were similar between the two arms. The rates of EBF for 6 months increased from 2% pre-intervention to 55.2% (95% CI 50.4–59.9) in the intervention group and 54.6% (95% CI 50.0–59.1) in the control group. The adjusted odds of EBF (after adjusting for baseline characteristics) were slightly higher in the intervention arm compared to the control arm but not significantly different: for 0–2 months (OR 1.27, 95% CI 0.55 to 2.96; p = 0.550); 0–4 months (OR 1.15; 95% CI 0.54 to 2.42; p = 0.696), and 0–6 months (OR 1.11, 95% CI 0.61 to 2.02; p = 0.718).

Conclusions

EBF for six months significantly increased in both arms indicating potential effectiveness of using CHWs to provide home-based counselling to mothers. The lack of any difference in EBF rates in the two groups suggests potential contamination of the control arm by information reserved for the intervention arm. Nevertheless, this study indicates a great potential for use of CHWs when they are incentivized and monitored as an effective model of promotion of EBF, particularly in urban poor settings. Given the equivalence of the results in both arms, the study suggests that the basic nutritional training given to CHWs in the basic primary health care training, and/or provision of information materials may be adequate in improving EBF rates in communities. However, further investigations on this may be needed. One contribution of these findings to implementation science is the difficulty in finding an appropriate counterfactual for community-based educational interventions.

Trial registration

ISRCTN ISRCTN83692672. Registered 11 November 2012. Retrospectively registered.

Similar content being viewed by others

Background

The global strategy for infant and young child nutrition (IYCN) aims to revitalize efforts to protect, promote and support appropriate infant and young child feeding [1]. Bhutta et al. listed the promotion of breastfeeding and providing supportive strategies as one of the ten evidence-based high impact interventions for improvement of infant and child nutrition and survival [2]. Such strategies may include the Baby Friendly Hospital Initiative (BFHI), a global strategy which promotes breastfeeding in maternity wards around the time of delivery and has been shown to be effective in some settings particularly in the more developed countries [3, 4]. However, in less developed countries, where many deliveries do not occur in health facilities, [5] the effectiveness of the BFHI may be limited.

In Kenya, like in other low and middle income countries (LMICs), poor IYCN practices have been documented widely. To optimize IYCN practices in the country, the Government adapted the WHO/UNICEF global IYCN strategy into a national strategy, [1, 6] actualized through the BFHI. However, most activities have been hospital/clinic based with little extension of breastfeeding counselling and support to the mother in the community after discharge. Furthermore, many deliveries do not occur in health facilities, [7, 8] thereby limiting the impact of BFHI on breastfeeding and other infant feeding practices. Recognizing the need to also reach women at the community level, the Ministry of Health has proposed adoption of the Baby Friendly Community Initiative (BFCI), a global initiative, also developed by WHO and UNICEF, which extends the principles of BFHI at the community level, to complement the BFHI in promotion of optimal breastfeeding and other MIYCN practices (http://bit.ly/2iY7fvV).

The effectiveness of community-based interventions which use CHWs to promote health including optimal breastfeeding practices has been documented, especially among difficult-to-reach predominantly rural populations, but rarely among the urban poor [2, 9,10,11]. In sub-Saharan Africa (SSA), about 60% of urban residents live in slum settlements, [12] where social and health services are limited, and many women either deliver at home or at sub-standard private health facilities [13]. This means that many of these women may not benefit from the counselling on IYCN offered through the BFHI. In the urban slums of Nairobi, a study conducted in 2007 found that barely 2 % of infants were exclusively breastfed for the first six months. Close to half of children under the age of five in these settings were stunted [14]. The reasons given by mothers for poor breastfeeding and infant feeding practices were: lack of adequate breast milk; poor knowledge; lack of support from health professionals to lactating mothers; food insecurity; and women’s occupations that are incompatible with EBF [15, 16]. These findings reflect both individual and structural factors which can be addressed with targeted counselling and other support.

We designed a cluster randomized controlled trial to test the effectiveness of personalized home-based nutritional counselling by CHWs on MIYCN practices, and consequently on morbidity and nutritional outcomes of infants in two Nairobi slums [17]. The focus of this paper is to determine the effectiveness of this intervention on EBF in the first six months.

Methods

The study protocol is already published [17]. For this paper we only detail methods relevant to the research question.

Study setting

The study was carried out in two slums of Nairobi, Kenya (Korogocho and Viwandani) where the African Population and Health Research Center (APHRC) operates the Nairobi Urban Health and Demographic Surveillance System (NUHDSS), covering close to 70,000 residents. The two slums are densely populated with roughly 60,000 inhabitants per square km and are characterized by poor housing, lack of basic infrastructure, violence, insecurity, high unemployment rates and poverty, food insecurity and poor health indicators including poor IYCN practices, high levels of malnutrition and mortality [14, 18,19,20,21,22].

Study design and randomization

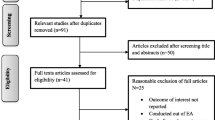

This was a cluster randomized controlled trial [23]. Randomization of the community units (CUs) to the intervention or control arm was computer-generated by a data analyst who was not a primary member of the study team. (A CU as defined by the Kenyan Community Health Strategy is geographically defined with an approximate population of 5000 people. Where the CUs did not exist, APHRC facilitated their set-up). Before randomization, clusters were stratified by slum of residence and the number of women of reproductive age in each cluster (large or small clusters). Fourteen CUs, eight in Korogocho and six in Viwandani were equally randomized into either intervention or control arm. Cluster randomization was preferred over individual-level randomization in order to minimize contamination and for pragmatic purposes as CHWs work in clusters. Figure 1 illustrates the outcome of the randomization process.

Randomization of Study participants to Intervention and Control Groups, MIYCN Study, Nairobi Slums. 1Excluded or dropped due to loss to follow-up during pregnancy due to migration or death of mother, giving birth before receiving the intervention and pregnancy loss (miscarriage/abortion or still birth). 2Lost to follow up after giving birth due to migration, or death of mother or the baby

Study subjects

Participants were recruited from any pregnant girls and women aged between 12 and 49 years, who were resident within the defined study area. Girls aged 12–14 years were included because close to 10% of girls below 15 years are sexually active, and from the qualitative work in the study areas young women reported that they need MIYCN counselling [16, 24]. The exclusion criteria were: (a) recruited women who gave birth before receiving the intervention; (b) women with disability that would make delivery of the intervention difficult e.g. intellectual impairment, or who bore a child with a disability that would make feeding difficult; (c) women who lost the pregnancy and/or had a still-birth after being recruited in the intervention; and (d) pregnant women who were lost to follow-up before they delivered.

Efforts to recruit all eligible women were made by using the routine NUHDSS rounds complemented by use of key community informants. All known pregnant women were invited to participate in the study. The target was to recruit the women as early as possible during pregnancy. After obtaining written informed consent, recruitment was done by the data collectors on a rolling basis from September 2012 to February 2014 until the desired sample size was achieved.

Sample size

The sample size calculation took into account clustering of women in the CUs. A minimum sample size for both intervention and control arms of 196 was estimated to have enough power to detect an increase in EBF for six months from baseline rate of 2% in the study setting [15] to 12%. We used a significance level of 5% and power of 80%. We adjusted for expected intra-cluster correlation (ICC) using a design effect of 3.2 based on an ICC of 0.05, according to previous research in the study area [25]. Allowing for a 20% potential attrition, the sample size of 780 mother-child pairs was estimated. To increase usefulness of the secondary outcomes analysis, we increased the sample size, ending up with a sample size of 1100 at the end of the follow-up.

Intervention

The experimental intervention involved personalized home-based nutritional counselling of women from the time of recruitment until the baby attained one year. Scheduled visits were: pregnancy - monthly until week 34, then weekly until delivery; mother and baby pairs – weekly in the first month then monthly until12 months. Frequency during the fifth month was biweekly to prepare mothers for complementary feeding. CHWs were given a visiting schedule (Appendix 3) with appropriate key messages at each visit depending on the pregnancy gestational age and age of baby. The expected number of scheduled visits were a total of 7 during pregnancy and 17 after delivery. For each visit the CHW was given a sheet detailing what information to ask for and specific message(s) to give to the mother. Nutritional counselling messages encompassed maternal nutrition, immediate initiation of breastfeeding after birth, breast positioning and attachment, exclusive breastfeeding, frequency and duration of breastfeeding, expressing breast milk, storage, handling and feeding of expressed breast milk and lactation management. It also included age-appropriate complementary feeding. Counselling was also informed by the stages of change model [26]. We did not establish or test the HIV status of participants in this study, but the CHWs in the intervention arm were trained on infant feeding in the context of HIV and were expected to incorporate this in the counselling, without establishing HIV status of the mother. Further, the CHWs were advised to counsel mothers to seek further counselling and support at the health facilities in the event they were HIV positive.

To help in the adaptation of the counselling messages and to inform the design of the intervention, a qualitative study was conducted before the roll-out of the intervention [16, 17]. Additionally, consultations were held with key institutions including the Ministry of Health, UNICEF and other organizations working on MIYCN issues in the community.

Intervention CHWs within the study area recruited from the Community Units in the Community Health Strategy were trained using the Community Infant and Young Child Feeding (IYCF) Counselling Package developed by UNICEF and other partners. This package has been adopted by the Kenya Ministry of Health (http://uni.cf/1QavG2g), based on the WHO IYCF integrated course [27]. Each CHW was given a copy of the counselling cards; brightly colored illustrations that depict key infant and young child feeding concepts. For the intervention CHWs, two follow up training workshops with case discussions were also done. The CHWs were also directly observed intermittently while they counselled women in the households and given feedback.

CHWs in the control arm were not trained on MIYCN but were trained (through the regular government facilitated training) together with the intervention CHWs on standard care, which included ante-natal and post-natal care, family planning, water, sanitation and hygiene, delivery with skilled attendance, immunization and community nutrition. We optimized standard care by ensuring that the intended standard care happened. We therefore facilitating the government to set up Community Units where they did not exist through recruitment of CHWs into the units and offering the CHWs with basic training in order to provide standard counselling. We also provided incentives for CHVs as intended in the Community Health Strategy.

Community health workers in the control arm were expected to visit the mothers according to the standard practice prescribed in the Community Health Strategy, which is defined by need, but generally about once a month per household, and usually more frequent around the time of birth. No specific schedule was given to them.

All recruited pregnant women, whether in the intervention or control arm, received standard care which included counselling from CHWs on primary health care and antenatal and postnatal care and information materials regarding MIYCN.

A total of 30 CHWs across the intervention and control arms were involved in the study. The CHWs in both arms were given a monthly incentive of KES 3500 (approx. USD 35), which is within the government’s approved monthly incentive for CHWs but is rarely implemented. Routine monitoring and supervision of the CHWs was conducted primarily by an Intervention Monitor, and sometimes by other members of the project team, and government officers from the community health strategy. In addition midline and endline qualitative studies involving in-depth interviews and focus group discussion with mothers and CHWs were done among both intervention and control group.

An outline of what was given to intervention vs. control group is given on Table 1. The main differences between the intervention and control arms were that in the intervention arm, the CHWs were given specific training on MIYCN and given counselling cards, while in the control group CHWs were not trained on MIYCN. Also, the in the intervention arm, CHWs were given a specific work schedule to follow up mothers, while no schedule was given to the CHWs in the control group. The CHVs in both intervention and control arms had at least primary level education.

Data collection

Interviewer administered questionnaires were used to collect breastfeeding data and information on control variables as described below.

Outcome measure

Data on breastfeeding practices were collected every two months until the infant’s first birthday. We used the WHO definition of EBF as “no other food or drink”, not even water, except breast milk for 6 months of life, but allowing the infant to receive ORS, drops and syrups (vitamins, minerals and medicines) [28]. In terms of measuring this, we used a three day recall to determine if the child had been initiated on other foods. Questions that were asked to establish exclusive breastfeeding included: (i) If the child was given anything other than breast milk in the first three days of life; then at each visit (ii) we asked if the child was given anything other than breast milk in the last three days; (iib) If yes to ii, we asked what the child was given and the age of starting the food/drink; (iii) If no to ii, we asked if the child has ever been given food/drink other than breast milk; (iiib) If yes to iii, we asked what the child was given and the age of starting the food/drink. To determine if the child was exclusively breastfed since birth, we used questions i, ii, and iii. So any mother who reported any deviation from the definition was relegated to a nonexclusive breastfeeding group. To determine at what age the child was given anything other than breast milk, we used questions i, iib, and iiib.

Control variables

Control variables collected at baseline and at birth (for example place of delivery) included: household food security assessed using the household food insecurity access scale (HIAS) [29], maternal demographic and socio-economic status; household wealth status; proxy for knowledge on EBF defined by mothers’ knowledge that foods/drinks (other than breast milk) should be introduced at six months, and no pre-lacteal feeds in the first three days of birth; and place of delivery, categorized into two: either at a health facility or other (home or TBA facility). This information is summarized in Table 2.

Statistical analysis

We used the Chi-square test, and adjusted for the cluster study design, baseline differences to compare the proportions of mother-child pairs practicing exclusive breastfeeding (EBF) for two, four and six months The attrition rate was variable between the intervention and control groups (22% versus 17%), and to account for any potential bias from selective attrition we used logistic regression and the baseline characteristics to provide adjusted odds ratios. The cluster study design was taken into account for both the adjusted and unadjusted odds ratios. Intention to treat analysis [30] was applied as appropriate. Among those who were lost to follow-up, last observation carried forward (LOCF) was applied for those whose status as “not EBF” had been determined in the previous rounds of observation. For those whose status was not already established for any time point say two, four or six months (still exclusively breastfeeding in the last observation), LOCF was only used for the point that it was conclusively established, but was not used for latter points. Such an observation was considered as right-censored [31]. Quantitative data analysis was done using Stata version 12.1 (StataCorp LP, College Station, Texas, USA). Statistical significance was assessed with alpha = 0.05 (95% CI).

Ethical approval

Ethical approval was granted by the Kenya Medical Research Institute (KEMRI) Ethical Review Committee (Reference number: KEMRI/RES/7/3/1). Written informed consent was obtained from all participants. Proxy consent for children was obtained from their mothers.

Results

As shown in Fig. 1 (CONSORT diagram), a total of 1613 pregnant women were approached for recruitment, 799 in the intervention and 814 in the control clusters. Of these, 58 (4%) refused to be recruited into the study. Of those recruited, 242 (31%) in the intervention group and 203 (26% in the control group) were excluded because they lost the pregnancy, moved away from the study area, died, or because they gave birth before they received the intervention. Therefore, 1110 mother-child pairs were included in the study, 529 in the intervention and 581 in the control group. Of these, 210 (18.9%) were lost to follow-up at different time points in the study after delivery, 114 (22%) in the intervention and 96 (17%) in the control group, but were included in the analysis with respect to the intention to treat principle [30]. The high level of attrition may be attributed to high mobility rates in slum settings, facilitated by search for employment, with 22.5% out-migration annually [21].

Baseline characteristics

The baseline distribution of the participants by demographic and socioeconomic variables between the intervention and control arms of the study is presented in Table 2. The distributions show no significant difference in basic socio-demographic factors between the two arms. At baseline the majority of mothers (63% in the control and 62% in the intervention arms) knew about the proper timing of introduction of complementary foods. The majority of the children, 94% in the intervention and 96% in the control groups were born at health facilities (see Table 2).

As illustrated in Appendices 1 and 2, there was no difference in the baseline characteristics between the intervention and control arms among those who were excluded from the study due to loss to follow except for one variable (parity). A higher proportion (38%) of women excluded in the intervention group had no children compared to those excluded in the control group (29%), p = 0.04 (see Appendix 1). Comparison of characteristics of women who were included and those who were excluded showed that there were no differences except in religion and household food security. A lower proportion of those included was Muslim (9.5%) compared to those who were excluded (13%), while a higher proportion of those included was from food secure households (28%) compared to those excluded (21.5%). P < 0.001 (see Appendix 2).

Exclusive breastfeeding

Table 3 shows the proportions of children that were exclusively breastfed for two, four and six months, measured longitudinally.

A slightly higher proportion of children were breastfed exclusively for at least two months in the intervention group at 83.5% (95% CI 79.8–86.6) compared to the control group at 79.7% (95% CI 76.0–82.9), but the difference was not statistically significant. The prevalence of exclusive breastfeeding reduced with age: EBF for 0–4 months was 70.1% (95% CI 65.6–74.2) for the intervention group and 69.4% (95% CI 65.2–73.3) for the control group, while for 0–6 months this was 55.2% (95% CI 50.4–59.9) in the intervention group and 54.6% (95% CI 50.0–59.1) in the control group. There was no statistically significant difference in the rates of EBF by intervention status at all the points.

Regression analysis for exclusive breastfeeding

The unadjusted odds of EBF were slightly higher in the intervention arm compared to the control arm but there was no statistically significant difference. At two months (OR 1.29, 95% CI 0.62 to 2.69; p = 0.467); four months (OR 1.03; 95% CI 0.48 to 2.25; p = 0.929); and six months (OR 1.03, 95% CI 0.48 to 2.20; p = 0.941). The adjusted odds of EBF(after adjusting for baseline characteristics) were also slightly higher in the intervention arm compared to the control arm but not significantly different: for two months (OR 1.27, 95% CI 0.55 to 2.96; p = 0.550); four months (OR 1.15; 95% CI 0.54 to 2.42; p = 0.696), and six months (OR 1.11, 95% CI 0.61 to 2.02; p = 0.718). Adjusted odds ratios of EBF by selected characteristics are shown in Table 4.

Discussion

This cluster randomized controlled trial to determine the effectiveness of personalized home-based counselling by CHWs on exclusive breastfeeding for six months did not find a difference between the intervention and control arms. However, there was a large increase in both groups from a baseline of 2%, [15] to 55% in both arms. The study suggests that the basic nutritional training given to CHWs in the basic primary health care training, and/or provision of information materials may be adequate in improving EBF rates in communities significantly. However, further investigations to conclude on this may be needed.

Using data obtained through a parallel observation study on comparable women who gave birth in the surveillance area, but were not recruited into this study, EBF rates for 6 months were about 3% [32]. This shows that there was no noticeable change in the low EBF rates in these slums for the mother-baby pairs who were not part of this study. The large difference between the study groups and the comparison group in the parallel observation study may be attributed to regular CHWs’ visits for counselling and support and distribution of information materials to the mothers in both intervention and control groups, motivated by incentivizing CHWs to visit mothers in the study setting, and supervising them, hence optimizing the proposed standard primary health care that is hampered by lack of CHW motivation. However, there was some differences in the design of the two studies (intervention study and the observational study) that could result in difference in the outcomes. Though similar questions were asked to the mothers to establish exclusive breastfeeding in the two studies, mothers in the intervention study were recruited during pregnancy and followed up more regularly, while mothers in the observational study were recruited after birth and had fewer follow-up visits, meaning there would be longer recall periods to remember when exclusive breastfeeding ceased.

Given the nature of the intervention, it was not possible to blind the CHWs. Anecdotal evidence from the fieldworkers suggests that once the CHWs in the control group found out that the intervention group CHWs had received extra training and extra counselling materials (i.e. counselling cards), they vowed to work so hard that the women in their arm would perform better. While we did not train CHWs in the control arm on MIYCN, we discovered (through endline evaluation) that the two groups had similar levels of knowledge of MIYCN. For ethical reasons, both groups were given the standard government MIYCN information materials which may have enhanced the knowledge of the mothers and CHWs in both intervention and control groups. We also provided the same monetary incentives to the CHWs in both groups and routine supervision, which could have motivated the CHWs in both groups to visit the mothers, although we did not specifically explore this.

Nationally, there are campaigns to encourage mothers to practice EBF for six months which may be responsible for the improved national EBF rate from 32% in 2008 to 61% reported in the KDHS in 2014 [8]. Another key change that occurred was the adoption of the free maternity care policy in public health facilities (http://bit.ly/1QsLuZ2) since June 2013. This increased health facility deliveries nationally [8]. The free maternity policy could have led to the promotion of breastfeeding through counselling of mothers during antenatal care or delivery at the health facilities by health care workers. However, while free maternity care might have affected initiation rates, sustaining EBF for six months requires dedication and adequate support. Urban poor settings remain unreached due to poor access to health care and social services [16]. We believe that the regular follow up by CHWs in our study made a difference since the rate of EBF among mothers in the slums who were not in the study remained low during the study period, despite the changes nationally [32]. Other studies have found that regular CHW visits to mothers provide support and encouragement which are needed to overcome social barriers to EBF [33]. It is worth noting that our results may not be directly comparable to the results of the KDHS as the KDHS is a cross-sectional study which uses a 24 h recall method, while our study was a longitudinal one and used a more strict definition of EBF, reporting exclusive breastfeeding from birth to six months as described in the methods section.

Our study found a high level of improvement in EBF rates in both the control and intervention arms. Increases in EBF following home-based counselling have also been documented in other studies in Kenya and other LMICs, [11, 34, 35]. In a randomized controlled trial in urban poor settings in Nairobi, Kenya, Ochola et al... (2012) found that EBF in the group that received home-based intensive counselling (seven visits; one prenatally and six post-natally) by trained peers was 23.6% compared to the facility based arm that only received one counselling (pre-natally) (9.2%) and control group that did not receive counselling (5.6%). The home-based intensive counselling group had significantly higher (four times) likelihood of EBF compared to the control group (RR 4.01; 95% CI 2.30, 7.01; p = 0.001) [35]. A cluster randomized trial in Dhaka Bangladesh reported a prevalence of EBF at five months of 70% in the intervention compared to 6% in the control group which was over 10-fold increase in EBF [11]. The intervention group in the Dhaka study received counselling visits by trained lay counselors during the last trimester and post-partum until the child was five months, but no visits were reported for the control group. Wangalwa et al’s uncontrolled pre and post study in an agrarian rural setting in Kenya increased EBF from 20% to 52% through CHWs counselling [36]. Our findings are in line with the results of a systematic review in LMICs that found that community-based peer support decreased the risk of discontinuing EBF significantly as compared to control (RR: 0.71; 95% CI: 0.61–0.82), [34] and another systematic review of 20 trials which found that interventions with a post-natal component were effective in improving breastfeeding practices [37]. While studies have also documented a remarkable effect of hospital-based breastfeeding support around the time of birth on EBF, [4, 38] there is a significant drop in continued exclusive breastfeeding shortly after discharge from the hospital in the absence of continued support at the community level [38].

This study contributes to implementation science knowledge, but the lack of appropriate counterfactual in our study is a key limitation in accurately assessing the effect of the intervention. However, the lack of improvement in EBF among women who were not part of our study helps to explain the potential effect of our intervention [32]. Other limitations in this study may include potential bias in reporting of the primary outcome (exclusive breastfeeding), often associated with self-reported outcomes, particularly due to social desirability in the context of an intervention. However, the fact that we asked several questions longitudinally to determine EBF gives us confidence in the estimates. High mobility in the urban slums [21] meant that some of the participants were lost to follow-up. To minimize attrition bias, we used intention-to-treat analysis [30]. We can also not rule out a Hawthorne effect since mothers who were in the control group knew that they were part of the study because of the frequent measurements on the infants that we took at given time points. Finally, the results from our study show an intra-cluster correlation coefficient (ICC) of about12%. In our sample size calculation we assumed an ICC of 5% which is lower than the true value. The implications of this are that with a higher ICC, we would have needed a bigger sample size than we estimated but given that the change in the outcome variable (2% to 55%) found in this study is much higher than we had estimated (2% to 12%) the under-estimation of the ICC is not problematic. This would have been a problem if the change in EBF prevalence had been small. Given the similar improvements in the percentage of infants being breastfed in both groups, it is unlikely that a larger sample would have led to different findings.

Conclusions

This study indicates potential effectiveness of home-based nutritional counselling by CHWs in improving EBF. The study also suggests that the basic nutritional training given to CHWs in the basic primary health care training, and/or provision of information materials may be adequate in improving EBF rates in communities significantly. This raises the question on the need to have additional MIYCN training for CHWs as well as the intensive scheduled home-based nutritional counselling visits, which may not adequately be answered in this study, and may need further investigation. In line with findings from other studies, [34,35,36,37,38] the study provides evidence of the importance of antenatal, perinatal and post-natal home-based breastfeeding support. The decision by the Kenyan government to scale-up the BFHI and to adopt the BFCI is likely to be effective in promoting EBF in Kenya. While this study contributes to implementation science knowledge, it demonstrates the difficulty of finding an appropriate counterfactual for community-based educational interventions. Nevertheless, this study indicates a great potential for use of CHWs when they are incentivized and monitored as an effective model of promotion of EBF, particularly in urban poor settings [15, 16]. The results of this study are relevant for sub-Saharan African countries which are implementing or likely to implement the BFCI.

Abbreviations

- APHRC:

-

African Population and Health Research Center

- BFCI:

-

Baby Friendly Community Initiative

- BFHI:

-

Baby-friendly Hospital Initiative

- CHW:

-

Community Health Worker

- CI:

-

Confidence interval

- CONSORT:

-

Consolidated Standards of Reporting Trials

- CU:

-

Community Unit

- EBF:

-

Exclusive breastfeeding

- HIAS:

-

Household food insecurity access scale

- ICC:

-

Intra-cluster correlation

- IYCF:

-

Infant and young child feeding

- IYCN:

-

Infant and young child nutrition

- KEMRI:

-

Kenya Medical Research Institute

- KES:

-

Kenya shilling

- LMICs:

-

LOCF, last observation carried forward; Low- and middle-income countries

- MIYCN:

-

Maternal, infant and young child nutrition

- NUHDSS:

-

Nairobi Urban Health and Demographic System

- OR:

-

Odds Ratio

- RR:

-

Relative risk

- SSA:

-

Sub-Saharan Africa

- TBA:

-

Traditional birth attendant

- UNICEF:

-

United Nations Children’s Fund

- USA:

-

United States of America

- USD:

-

United States Dollar

- WHO:

-

World Health Organization

References

WHO: Global strategy for infant and young child feeding. In. Geneva: WHO 2003.

Bhutta ZA, Das JK, Rizvi A, Gaffey MF, Walker N, Horton S, et al. Evidence-based interventions for improvement of maternal and child nutrition: what can be done and at what cost? Lancet. 2013;382(9890):452–77.

Perez-Escamilla R. Evidence based breast-feeding promotion: the baby-friendly hospital initiative. J Nutr. 2007;137(2):484–7.

Martens PJ. What do Kramer’s baby-friendly hospital initiative PROBIT studies tell us? A review of a decade of research. J Hum Lact. 2012;28(3):335–42.

Montagu D, Yamey G, Visconti A, Harding A, Yoong J. Where do poor women in developing countries give birth? A multi-country analysis of demographic and health survey data. PLoS One. 2011;6(2):e17155.

Ministry of Public Health and Sanitation: National Strategy on Infant and Young Child Feeding Strategy 2007–2010. Ministry of Public Health and Sanitation, Kenya. Nairobi, 2007. URL: http://bit.ly/212WAw1; Accessed on 18th November 2015.

Kenya National Bureau of Statistics (KNBS), ICF Macro: Kenya Demographic and Health Survey 2008–09: Calverton, Maryland: KNBS and ICF Macro; 2009. URL: http://dhsprogram.com/pubs/pdf/fr229/fr229.pdf; Accessed on 18th November 2015.

Kenya National Bureau of Statistics, Ministry of Health, National AIDS Control Council, Kenya Medical Research Institute, National Council for Population and Development: Kenya Demographic and Health Survey 2014: Key Indicators Report. Nairobi; 2015. URL: https://dhsprogram.com/pubs/pdf/PR55/PR55.pdf; Accessed on 18th November 2015.

Bhutta AZ, Lassi ZS, Pariyo G, Huicho L: Global experience of community health workers for delivery of health related Millennium Development Goals: a systematic review, country case studies and recommendation for integration into national health systems. In. Geneva: World Health Organization: Global Health Workforce Alliance; 2010. URL: http://www.who.int/workforcealliance/knowledge/resources/chwreport/en/; Accessed on 18th November 2015.

Haines A, Sanders D, Lehmann U, Rowe AK, Lawn JE, Jan S, Walker DG, Bhutta Z. Achieving child survival goals: potential contribution of community health workers. Lancet. 2007;369(9579):2121–31.

Haider R, Ashworth A, Kabir I, Huttly S. Effect of community-based peer counsellors on exclusive breastfeeding practices in Dhaka, Bangladesh: a randomised controlled trial. Lancet. 2000;356:1643–7.

UNHABITAT. State of the World's cities 2010/2011: bridging the urban divide. London: UNHABITAT; 2008.

Fotso JC, Ezeh A, Madise N, Ziraba A, Ogollah R. What does access to maternal care mean among the urban poor? Factors associated with use of appropriate maternal health services in the slum settlements of Nairobi, Kenya. Matern Child Health J. 2009;13(1):130–7.

Kimani-Murage EW, Muthuri SK, Oti SO, Mutua MK, van de Vijver S, Kyobutungi C. Evidence of a double burden of malnutrition in urban poor settings in Nairobi, Kenya. PLoS One. 2015;10(6):e0129943.

Kimani-Murage E, Madise N, Fotso J-C, Kyobutungi C, Mutua K, Gitau T, et al. Patterns and determinants of breastfeeding and complementary feeding practices in urban informal settlements, Nairobi Kenya. BMC Public Health. 2011;11(396)

Kimani-Murage EW, Wekesah F, Wanjohi M, Kyobutungi C, Ezeh AC, Musoke RN, et al. Factors affecting actualisation of the WHO breastfeeding recommendations in urban poor settings in Kenya. Matern Child Nutr. 2014;

Kimani-Murage EW, Kyobutungi C, Ezeh AC, Wekesah F, Wanjohi M, Muriuki P, et al. Effectiveness of personalised, home-based nutritional counselling on infant feeding practices, morbidity and nutritional outcomes among infants in Nairobi slums: study protocol for a cluster randomised controlled trial. Trials. 2013;14:445.

Kimani-Murage EW, Schofield L, Wekesah F, Mohamed S, Mberu B, Ettarh R, et al. Vulnerability to food insecurity in urban slums: experiences from Nairobi, Kenya. J Urban Health. 2014;91:1098–113.

Kimani-Murage EW, Fotso JC, Egondi T, Abuya B, Elungata P, Ziraba AK, et al. Trends in childhood mortality in Kenya: the urban advantage has seemingly been wiped out. Health Place. 2014;29C:95–103.

Mberu BU, Ciera JM, Elungata P, Ezeh AC. Patterns and determinants of poverty transitions among poor urban households in Nairobi. Afr Dev Rev. 2014;26:172–85.

Beguy D, Elung'ata P, Mberu B, Oduor C, Wamukoya M, Nganyi B, et al. Health & Demographic Surveillance System Profile: the Nairobi urban health and demographic surveillance system (NUHDSS). Int J Epidemiol. 2015;44(2):462–71.

Emina J, Beguy D, Zulu EM, Ezeh AC, Muindi K, Elung’ata P, et al. Monitoring of health and demographic outcomes in poor urban settlements: evidence from the Nairobi urban health and demographic surveillance system. J Urban Health. 2011;88(Suppl 2):S200–18.

Campbell MK, Elbourne DR, Altman DG. CONSORT statement: extension to cluster randomised trials. BMJ. 2004;328(7441):702–8.

Ndugwa RP, Kabiru CW, Cleland J, Beguy D, Egondi T, Zulu EM, et al. Adolescent problem behavior in Nairobi's informal settlements: applying problem behavior theory in sub-Saharan Africa. J Urban Health. 2011;88(Suppl 2):S298–317.

Fotso JC, Madise N, Baschieri A, Cleland J, Zulu E, Mutua MK, et al. Child growth in urban deprived settings: does household poverty status matter? At which stage of child development? Health Place. 2012;18(2):375–84.

Prochaska JO, Velicer WF. The transtheoretical model of health behavior change. Am J Health Promot. 1997;12(1):38–48.

WHO: Infant and Young Child Feeding Counselling: An Integrated Course. Geneva: WHO Document Production Services; 2006.

World Health Organization: Indicators for assessing breastfeeding practices: reprinted report of an informalmeeting 11–12 June, 1991. In. Geneva: World Health Organization; 1991. URL: http://apps.who.int/iris/bitstream/10665/62134/1/WHO_CDD_SER_91.14.pdf; Accessed on 18th November 2015.

Coates J, Anne S, Paula B. Household Food Insecurity Access Scale (HFIAS) for Measurement of Household Food Access: Indicator Guide (v. 3). Washington, D.C: Food and Nutrition Technical Assistance Project, Academy for Educational Development, 2007. URL: http://www.fao.org/fileadmin/user_upload/eufao-fsi4dm/doc-training/hfias.pdf; Accessed on 18th November 2015.

Sainani KL. Making sense of intention-to-treat. PM R. 2010;2(3):209–13.

Lydersen S. Statistical review: frequently given comments. Ann Rheum Dis. 2015;74(2):323–5.

Kimani-Murage EW, Norris SA, Mutua MK, Wekesah FM, Wanjohi M, Muhia N, et al. Potential effectiveness of community health strategy to promote exclusive breastfeeding in urban poor settings in Nairobi, Kenya: a quasi-experimental study. J Dev Orig Health Dis. 2015;28:1–13.

Perry M, Becerra F, Kavanagh J, Serre A, Vargas E. V. B: community-based interventions for improving maternal health and for reducing maternal health inequalities in high-income countries: a systematic map of research. Glob Health. 2015;

Sudfeld CR, Fawzi WW, Lahariya C. Peer support and exclusive breastfeeding duration in low and middle-income countries: a systematic review and meta-analysis. PLoS One. 2012;7(9):e45143.

Ochola SA, Labadarios D, Nduati RW. Impact of counselling on exclusive breast-feeding practices in a poor urban setting in Kenya: a randomized controlled trial. Public Health Nutr. 2013;16(10):1732–40.

Wangalwa G, Cudjoe B, Wamalwa D, Machira Y, Ofware P, Ndirangu M, et al. Effectiveness of Kenya's community health strategy in delivering community-based maternal and newborn health care in Busia County, Kenya: non-randomized pre-test post test study. Pan Afr Med J. 2012;13(Suppl 1):12.

Sikorski J, Renfrew MJ, Pindoria S, Wade A. Support for breastfeeding mothers: a systematic review. Paediatr Perinat Epidemiol. 2003;17(4):407–17.

Coutinho SB, de Lira PI, de Carvalho Lima M, Ashworth A. Comparison of the effect of two systems for the promotion of exclusive breastfeeding. Lancet. 2005;366(9491):1094–100.

Acknowledgements

We are grateful to the Unit of Nutrition and Dietetics and the Unit of Community Health Services of the Ministry of Health, Kenya, for their guidance in the design of the intervention and their continued support of the implementation of the project including in identification and training of Community Health Workers and provision of educational materials for the intervention. We would also like to thank UNICEF, Concern World Wide, Makadara and Embakasi sub-County Health Management Teams, the National Maternal Infant and Young Child Nutrition Steering Committee, the Urban Nutrition Working Group, and the Nutrition Information Working Group, among other agencies/NGOs/groups for their contribution to the design and/or implementation of this study. We thank the APHRC Research Staff for their technical support in the design of the study. PG is supported by a British Academy mid-career fellowship (Ref: MD120048). The authors are highly indebted to the data collection and management team and the study participants.

Funding

This study was funded by the Wellcome Trust, Grant # 097146/Z/11/Z. We also acknowledge core funding for APHRC from The William and Flora Hewlett Foundation and the Swedish International Cooperation Agency (SIDA); and funding for the NUHDSS from the Bill and Melinda Gates Foundation.

Availability of data and materials

Data related to this article would be available upon request through the online micro-data portal http://aphrc.org/catalog/microdata/index.php/catalog/87.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

EWK-M: Was the principal investigator and directed the study, designed the study, had full access to all the data in the study and reviewed the analysis, wrote the manuscript and gave the final approval for submission of the manuscript for publication; PLG: Designed the study, reviewed data analysis, guided the writing of the manuscript, reviewed the manuscript and approved the manuscript for submission; FMW, MW, NM, and PM: Designed the study, supervised field work, reviewed the manuscript and approved the manuscript for submission; TE: Analyzed the data, reviewed the manuscript and approved the manuscript for submission; CK, ACE, RNM: Designed the study, reviewed the manuscript and approved the manuscript for submission, trained the CHWs; STM: Guided the writing of the manuscript, reviewed the manuscript and approved the manuscript for submission; SAN: Designed the study, guided the writing of the manuscript, reviewed the manuscript and approved the manuscript for submission; NJM: Designed the study, reviewed data analysis, guided the writing of the manuscript, reviewed the manuscript and approved the manuscript for submission.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

Ethical approval was granted by the Kenya Medical Research Institute (KEMRI) Ethical Review Committee (Reference number: KEMRI/RES/7/3/1). Written informed consent was obtained from all participants. Proxy consent for children was obtained from their mothers.

Consent for publication

No individual person data is included in this manuscript.

Competing interests

The authors have no competing interests to declare.

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Appendices

Appendix 1

Appendix 2

Appendix 3

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made. The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver (http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/) applies to the data made available in this article, unless otherwise stated.

About this article

Cite this article

Kimani-Murage, E.W., Griffiths, P.L., Wekesah, F. et al. Effectiveness of home-based nutritional counselling and support on exclusive breastfeeding in urban poor settings in Nairobi: a cluster randomized controlled trial. Global Health 13, 90 (2017). https://doi.org/10.1186/s12992-017-0314-9

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s12992-017-0314-9