Abstract

Background

Recent hypotheses have suggested that schizophrenic patients are more likely to consume unhealthy foods, causing increased rates of mortality and morbidity associated with metabolic syndrome. This raises the need for more in-depth research on disordered eating behaviors (DEBs) in schizophrenic patients. This study, therefore, aimed to investigate biopsychosocial factors associated with DEBs in schizophrenia.

Methods

In this cross-sectional study, a total of 308 participants (including 83 subjects in the active phase of schizophrenia, 71 subjects in the remission phase of schizophrenia, and 154 control subjects) were recruited through convenience sampling among patients who referred to the Baharan Psychiatric hospital in Zahedan, Iran. Patients were assessed through Eating Attitudes Test (EAT-26), Beck Anxiety Inventory (BAI), Beck Depression Inventory (BDI-II), and Positive and Negative Syndrome Scale (PANSS). Data were analyzed using SPSS v25 software. Further, the statistical significance level was set at p < 0.05.

Results

The prevalence of DEBs was 41.5% in schizophrenic patients (vs. 10.3% in the control group, p = 0.012). No significant difference was observed in the EAT-26 scores based on gender and phases of schizophrenia. According to multiple linear regression analysis, lack of psychosocial rehabilitation, use of atypical antipsychotics, early stages of psychosis, high level of anxiety and depression, expression of more active psychotic symptoms, tobacco smoking, and suffering from type 2 diabetes were all associated with increased development of DEBs among schizophrenic patients.

Conclusions

Since the occurrence of DEBs is independent of different phases of schizophrenia, the risk of DEBs is required to be evaluated during the entire course of schizophrenia especially at earlier stages of schizophrenia. Moreover, the use of psychosocial interventions, treatment of affective disorders (i.e., anxiety and depression), antipsychotic medication switching, treatment of tobacco smoking and type 2 diabetes may reduce the risk of DEBs among schizophrenic patients. However, further investigations are required to prove the actual roles of the above factors in developing DEBs among schizophrenic patients.

Similar content being viewed by others

Background

As a convoluted topic, disordered eating behaviors (DEBs) need to be recognized and defined [1]. The manifestations of DEBs may include behaviors such as binge eating, food restriction, and purging that are commonly related to feeding and eating disorders (FEDs) [2]. Nevertheless, these symptoms are less frequent or at a lower level of severity and might not be as extreme as symptoms of diagnosable FEDs [1, 2]. Furthermore, subjects who exhibit these behaviors may be at risk, both physically and emotionally [2].

Recent hypotheses have implied that schizophrenic patients more probably consume unhealthy foods, provoking escalated rates of mortality and morbidity attributed to metabolic syndrome [3]. This emphasizes the need for further in-depth research into DEBs in schizophrenic patients. Patients with DEBs are often characterized by a lack of control over their eating behaviors, known as “voracious gorging”, or as a form of environmental automatism [2, 3]. Despite the introduction of disorganized and uncontrolled food intake by Kraepelin [4] and Bleuler [5] as one of the characteristics of schizophrenia in the nineteenth century, the literature on this problem is still scarce because no sole criterion has been presented to provide a definite diagnosis of DEBs [6,7,8]. This has caused DEBs to be a secondary concern for clinicians [9]. In this respect, a recent hypothesis has suggested that DEBs may be a physiological compensatory mechanism in reducing psychotic symptoms, as starvation induces psychosis in individuals [3]. The most famous illustration of starvation-induced psychosis is related to the Minnesota study, wherein two healthy male volunteers showed similar behaviors following 24 weeks of starvation to patients with schizophrenia and anorexia nervosa [3].

Although various studies have focused on schizophrenia with comorbidity of FEDs such as anorexia nervosa, bulimia nervosa, binge eating, and other specified feeding and eating disorders (especially night eating syndrome), the pathophysiology of DEBs in schizophrenia has remained unknown [6, 10]. Depression and/or anxiety, sleep disturbances, socioeconomic adversity, side effects of psychiatric medications, tobacco smoking, and type 2 diabetes have been believed to be the risk factors for DEBs in schizophrenic patients [11]. Consistent with these findings, recent studies have revealed that over 70% of individuals with DEBs have a history of depression and/or anxiety before or after the onset of problematic eating behaviors [2, 12]. Bruch [13], for instance, considered overeating as an adaptive defense against stress among schizophrenic patients, which is utilized for the maintenance of self-control. She claimed that heavier people would not develop psychosis and used Kallman’s [14] monozygotic twin study argument to support this hypothesis. However, these early descriptions fail to explain cognitive awareness or deliberate behavior.

Additionally, recent animal and clinical researches have suggested that antipsychotics can lead to changes in dietary habits and hyperphagic effects, thereby causing a lack of satiation and increased appetite [15,16,17]. This evidence is consistent with previous research on schizophrenia patients, indicating that the treatment with atypical antipsychotics is associated with more frequent DEBs compared to typical antipsychotics [18,19,20,21]. In this regard, Sallemi et al. [16] used the SCOFF questionnaire to examine 53 Tunisian patients and reported DEBs among 35.8% of participants (mostly women and those with the use of atypical neuroleptics). Besides, Sentissi et al. [21] evaluated eating behaviors of 153 schizophrenic patients using the Three-Factor Eating Questionnaire (TFEQ) and reported that DEBs in patients are influenced by gender and treatment with atypical antipsychotics. On the other hand, no correlation was observed between medication use, duration of psychosis, and TFEQ scores in the study conducted by Kouidrat et al. [22] on 66 French schizophrenic patients. Also, their findings revealed no significant difference in TFEQ mean scores between male and female adults.

Moreover, comorbid medical and tobacco smoking are prevalent in schizophrenic patients [23]. For example, the risks of tobacco smoking and type 2 diabetes development in these patients were reported 58–90% [23] and 23.9% [24], respectively. In this point, recent evidence has suggested that tobacco smoking and type 2 diabetes may be associated with DEBs in schizophrenic patients [25, 26], e.g., DEBs in approximately 40% of schizophrenic patients with type 2 diabetes [26].

Despite these few and scattered findings, no study has yet comprehensively and specifically examined the biopsychosocial factors in DEBs among schizophrenic patients. Since DEBs occurrence in schizophrenic patients is an acute problem that accounts for the development of FEDs, complicate weight loss efforts, obesity, cardiometabolic disorders and their risk factors need to be identified for developing effective prevention and treatment strategies [1, 2, 6, 22]. Thus, the present study aims to investigate the biopsychosocial factors in DEBs among schizophrenic patients.

Methods

Participants

This cross-sectional study was conducted from May 2018 to November 2019. Based on the Green’s method [27], a total of 154 patients with schizophrenia (83 subjects in the active phase and 71 subjects in the remission phase) were selected by convenience sampling method among the people who referred to Baharan psychiatric hospital in Zahedan, Iran. Also, the control group was recruited from residents of the same geographical area through one-to-one matching (case:control ratio of 1:1; n = 154). The inclusion criteria were as follows: (1) a diagnosis of schizophrenia based on Structured Clinical Interviews for DSM-5 (Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, 5th Edition): Research Version (SCID-5-RV) by a psychiatrist; (2) aged between 18 and 70; (3) for the control group, getting a score of < 21 in the 28-item General Health Questionnaire (GHQ-28) and approved mental health based on SCID-5-RV by the psychiatrist, except evidences for DEBs and FEDs which were not exclusion criterion. Exclusion criteria were specified as follows: (1) intellectual disability; (2) a history of neurological disorder; (3) the use of antidepressants or mood stabilizers in the previous 3 months; (4) hearing loss; (5) failing to fill the questionnaires properly. The socio-demographic information of the participants is presented in Table 1 (N = 308).

Procedures

After obtaining the ethical approval from the Research Center of the Medicine Faculty and prior permission from the relevant Ethics Committee with IR.ZAUMS.REC.1398.210 code of ethics, the subjects were given the consent form to sign. The study was performed in compliance with the declaration of Helsinki, i.e., subjects were told that their participation would be optional and they could leave the study for any reason. After obtaining informed consent from the participants, the psychiatrist evaluated all of the participants using GHQ-28 and SCID-5-RV to identify the three study groups (including active phase group, remission phase group, and control group). Next, the 26-item Eating Attitudes Test (EAT-26), Beck Anxiety Inventory (BAI), Beck Depression Inventory (BDI-II), and Positive and Negative Syndrome Scale (PANSS) questionnaires were given to them. Then, schizophrenic patients with DEBs (i.e., earning an EAT-26 score of ≥ 20) were evaluated in terms of levels of anxiety and depression, type 2 diabetes (according to fasting blood sugar (FBS) ≥ 136 mg/dL on two separate tests), tobacco smoking (yes/no), duration of psychosis (i.e., from 6 months to 2 years, 2 to 5 years, 5 to 10 years, and greater than or equal to 10 years), phases of schizophrenia (active or remission phases), severity of psychosis, and category of antipsychotic medications (typical or atypical). The questionnaires were anonymous to preserve the participants’ information confidential.

Measures

EAT-26

A Persian version of the EAT-26 was used to measure DEBs among participants. The EAT-26 is a 26-item questionnaire that comprises questions on dieting, bulimia and food preoccupation, and oral control. The questions No. 1 to 25 were scored on a 6-point Likert scale, as 0 = never, 0 = rarely, 0 = sometimes, 1 = often, 2 = usually, and 3 = always. The only reverse-scoring item was question 26. The questionnaire scores may vary between 0 and 78, where a total score of ≥ 20 in the survey represents DEBs. A Cronbach’s alpha of 0.75 was obtained for this questionnaire, implying that this measure had acceptable validity and reliability [28]. In this study, the Cronbach’s alpha coefficient for the EAT-26 was 0.80.

BAI

Anxiety symptoms were assessed with the Persian version of the BAI, which is a self-report 21-item questionnaire scored based on a four-point (0 to 3) Likert scale. The minimum and maximum scores are 0 and 63, respectively. Kaviani et al. [29] reported acceptable reliability and validity for the Persian version of the questionnaire (Cronbach’s alpha = 0.92). In this study, the Cronbach’s alpha coefficient for the BAI was 0.90.

BDI-II

Depressive symptoms were assessed with the Persian version of the BDI-II, which is a self-report 21-item questionnaire scored based on a four-point (0 to 3) Likert scale. The minimum and maximum scores are 0 and 63, respectively. Ghassemzadeh et al. [30] showed acceptable reliability and validity for the Persian version of the questionnaire (Cronbach’s alpha = 0.87). In this study, the Cronbach’s alpha coefficient was 0.88 for the BDI-II.

PANSS

Symptoms severity of schizophrenic patients was assessed with the Persian version of the PANSS, which is a 30-item questionnaire scored based on a 5-point Likert scale (1 = absent, 2 = minimal, 3 = moderate, 4 = severe, and 5 = extreme). The scores of the items were summed up, resulting in the minimum and maximum scores of 30 and 150, respectively. Cronbach’s alpha of this scale was estimated at 77%, and its validity was approved based on the factor analysis results [31]. In this study, the Cronbach’s alpha coefficient was 0.75 for the PANSS.

SCID-5-RV

SCID-5-RV is a semi-structured interview for major DSM-5 diagnoses, which is performed by a trained clinician or health expert familiar with the diagnostic criteria and classification of disorders in DSM-5. Several studies have reported acceptable reliability and validity of SCID-5-RV [32].

GHQ-28

GHQ-28 is a 28-item questionnaire wherein items are scored on a 0 to 3 scale. The overall scores range between 0 and 84. A score of ˂ 21 indicates a person’s mental health [33]. In this study, the Cronbach’s alpha coefficients for the GHQ-28 subscales of somatic symptoms, anxiety and insomnia, social dysfunction, and severe depression were 0.75, 0.75, 0.70, and 0.85, respectively, while it was 0.88 for the total scale.

Statistical analysis

Descriptive statistics were obtained for data analysis. The Chi-square test and Kruskal–Wallis test were performed for a socio-demographic comparison among the study groups. Moreover, independent t-test and analysis of variance (ANOVA) were carried out to compare the EAT-26 scores among schizophrenic patients with DEBs based on biopsychosocial factors. Also, ANOVA was used to compare outcomes’ mean scores of EAT-26, BAI, and BDI-II between three study groups. In ANOVA, the Scheffé test was applied to post hoc analysis. The point-biserial correlation coefficient, Pearson correlation coefficient, and Spearman’s rank correlation coefficient were used to assess the correlations between DEBs and biopsychosocial factors among schizophrenic patients with DEBs (i.e., getting an EAT-26 score of ≥ 20). The multiple linear regression analysis was performed to examine the linear relationship between the response (i.e., DEBs) and explanatory variables (i.e., biopsychosocial factors). Data were analyzed using SPSS v25 software, and the statistical significance level was set at p < 0.05.

Results

Preliminary analysis

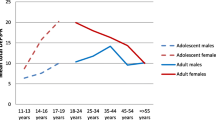

The DEBs were observed in 41.5% (n = 64) of schizophrenic patients (vs. 10.3% in the control group, p = 0.012), using the EAT-26. There was no significant difference in the EAT-26 scores regarding gender (t(62) = − 1.20, p = 0.231) and the phases of schizophrenia (t(62) = 1.16, p = 0.250). However, there were large differences in the EAT-26 scores concerning psychosocial rehabilitation (t(62) = − 3.43, p = 0.001), duration of psychosis (F(3, 60) = 11.34, p < 0.001), type of antipsychotic medications (t(42.20) = − 7.42, p < 0.001), tobacco smoking (t(16.90) = − 3.25, p = 0.005), and type 2 diabetes (t(14.16) = − 4.26, p = 0.001), as shown in Table 2. Comparisons of mean EAT-26, BAI, and BDI-II scores revealed significant differences among the three study groups including active phase group, remission phase group, and control group (F(2, 305) = 116.14, p < 0.001; F(2, 305) = 116.84, p < 0.001; F(2, 305) = 94.26, p < 0.001, respectively), such that the active phase group accounted for the highest scores of BAI (Fig. 1).

Clustered bar mean of Eating Attitudes Test (EAT-26), Beck Anxiety Inventory (BAI), and Beck Depression Inventory (BDI-II) by groups (error bars: 95% CI, ± 1 SD; N = 308). Analysis of variance (ANOVA). EAT-26: F(2, 305) = 116.14, p < 0.001; post hoc test: active phase, remission phase > control. BAI: F(2, 305) = 116.84, p < 0.001; post hoc test: active phase > remission phase > control. BDI-II: F(2, 305) = 94.26, p ˂ 0.001; post hoc test: active phase, remission phase > control

The correlations between DEBs and biopsychosocial factors

Significant correlations were found between DEBs (EAT-26 score of ≥ 20) and psychosocial rehabilitation (r = 0.40, p = 0.001), duration of psychosis (r = − 0.59, p < 0.001), category of antipsychotic medications (r = 0.67, p < 0.001), anxiety (r = 0.54, p < 0.001), depression (r = 0.48, p < 0.001), severity of psychosis (r = 0.53, p < 0.001), tobacco smoking (r = 0.51, p < 0.001), and type 2 diabetes (r = 0.59, p < 0.001), as can be seen in Table 3.

Biopsychosocial factors associated with DEBs among schizophrenic patients

According to multiple linear regression analysis, the biopsychosocial factors associated with DEBs among schizophrenic patients included psychosocial rehabilitation (β = 0.15, p = 0.042), duration of psychosis (β = − 0.18, p = 0.022), category of antipsychotic medications (β = 0.17, p = 0.045), anxiety (β = 0.16, p = 0.043), depression (β = 0.23, p = 0.003), severity of psychosis (β = 0.14, p = 0.047), tobacco smoking (β = 0.24, p = 0.007), and type 2 diabetes (β = 0.18, p = 0.035; F(8, 55) = 28.19, R2 = 0.80, p < 0.001), as presented in Table 4.

Discussion

The findings of the present study can be divided into five major parts. As the first part, the DEBs prevalence was 41.5% among schizophrenic patients (vs. 10.3% in the control group), using the EAT-26. However, the prevalence of DEBs among schizophrenic patients was 35.8% in the study by Sallemi et al. [16] through the SCOFF questionnaire, and 30% in the study conducted by Fawzi et al. [34] using the 40-item Eating Attitudes Test (EAT-40). The disparity in the frequency of DEBs between the present study and the studies by Sallemi et al. [16] and Fawzi et al. [34] may be due to the type of questionnaires, the number of participants, socio-demographic characteristics, and disregarding schizophrenic patients with type 2 diabetes and/or currently smoking patients. However, the above results confirmed the hypothesis that the prevalence of DEBs in schizophrenic patients is higher compared to the general population.

As the second part, no considerable difference was found in the EAT-26 scores based on gender. This finding is consistent with the results obtained by Kouidrat et al. [22], suggesting no significant gender difference in uncontrolled eating. However, a significantly higher risk of DEBs in the female gender was reported by Sallemi et al. [16] and Sentissi et al. [21]. Regardless of the results of Sallemi et al. [16] and Sentissi et al. [21], the present study together with wider literature proposed that DEBs were equally evident in men and women with schizophrenia, which is contrary to the general population that females are typically more affected [6]. Nevertheless, since EAT-26 is not specific to any FEDs (not even atypical or subthreshold ones), these findings should be used with caution.

As the third part, there were significant differences in the EAT-26 scores regarding the duration of psychosis and category of antipsychotic medications, which are consistent with the findings of Sallemi et al. [16], Sentissi et al. [21], Kouidrat et al. [6], Blouin et al. [18], and Fawzi et al. [34]. These results, however, are inconsistent with the results obtained by Kouidrat et al. [22] that showed no significant differences between TFEQ scores, category of antipsychotic medications, and duration of psychosis. These contradictory findings suggest that DEBs may represent a feature of schizophrenia regardless of medication use, such as antipsychotics [34]. Therefore, antipsychotic medication switching (as a strategy for reducing metabolic problems in schizophrenic patients) might not necessarily yield a better outcome [35]. In what follows, significant differences were observed in the EAT-26 scores regarding tobacco smoking and type 2 diabetes. These findings agree with those obtained by Essawy et al. [36] and García-Mayor et al. [26]. In this respect, tobacco smoking can increase the risk of internalizing, externalizing, and total behavioral problems (such as DEBs) by exacerbating interpersonal conflict and violence [25]. Further, in a similar direction, type 2 diabetes can raise the risk of developing DEBs due to dietary regimens, overweight, or obesity [26]. As an additional finding, the results of this study showed that psychosocial rehabilitation in schizophrenic patients was associated with a decrease in EAT-26 scores (discussed later).

As the fourth part, no significant difference was found in the EAT-26 scores concerning the phases of schizophrenia (active or remission phases). This finding was inconsistent with the results obtained by Khalil et al. [37], who demonstrated that DEBs decrease with psychotic episodes and recur when the psychotic episode remits. In this regard, DEBs may be a comorbid condition or part of the broad spectrum of psychotic disorders [8]. In other words, based on functional profiling of phenotypic manifestations, there may be a potential biologic overlap between subgroups of schizophrenia and DEBs. This caused DEBs to become phase-independent in some schizophrenic patients [8]. However, this hypothesis should be followed by a search for genetic correlates of variability.

As the fifth part, the results of the multiple linear regression analysis indicated that lack of psychosocial rehabilitation, use of atypical antipsychotics, an early stage of psychosis, high level of anxiety and depression, expression of more active psychotic symptoms, tobacco smoking, and type 2 diabetes were associated with increased development of DEBs among schizophrenic patients. These findings proposed that psychosocial rehabilitation accelerated the recovery from DEBs in schizophrenia. SAMHSA [38] defined recovery as “A process of change through which individuals improve their health and wellness, live a self-directed life, and strive to reach their full potential”. Accordingly, the following four domains support a recovering life: (1) health, i.e., overcoming and managing the disease while living in a physically and emotionally healthy manner; (2) home, i.e., a stable, constant, and safe place for living; (3) purpose, i.e., meaningful daily activities such as job, school, volunteerism, as well as creative endeavors, income, and resources, and (4) community, that involves communications and social networks providing support, friendship, love, and hope [38]. On this point, psychosocial interventions including Assertive Community Treatment (ACT), Supported Employment (SE), illness self-management training, family-based services, and Wellness Recovery Action Planning (WRAP) can mitigate stress and control DEBs in schizophrenic patients through rapid access to health services, medication management, job creation, as well as improvement in self-esteem, crisis intervention, emotional support, social interactions, and community reintegration. Furthermore, increasing the duration of psychosis through adaptation to a new reality of the illness can alleviate stress and, consequently, reduce overeating as an adaptive defense [39, 40]. However, it just might be a sign of the natural history of schizophrenia and FEDs—that FEDs usually happen earlier in life and schizophrenia is more prevalent later [41].

Concerning category of antipsychotic medications, the majority of the literature has suggested that uncontrolled eating behaviors are mostly influenced by treatment with atypical antipsychotics [18,19,20,21, 34]. This could partly explain the higher weight gain often reported in these patients in response to altered appetite sensations and increased susceptibility to hunger [18, 21]. On this detail, some mechanisms for gaining weight and increasing food intake related to antipsychotics are: (i) direct impacts on antipsychotics receptors; (ii) direct/indirect impacts on neuronal circuits (hypothalamus) that control satiety and food intake; (iii) disruption of the hypothalamic–pituitary–adrenal axis; (iv) direct influence on insulin secretion and sensitivity; (v) impacts on gastrointestinal hormones contained within food intake; (vi) diminished physical activity and reduced basal metabolism [6]. In fact, antipsychotic drugs are able to impact many neurotransmitter systems and take antagonistic actions on serotonin, dopamine, muscarinic, histamine, and adrenergic receptors [42]. All former neurotransmitters have had involvements (directly or indirectly) in the pathways related to regulating food intake [43], weight balance [44, 45], and metabolism [46, 47]. Blockades of serotonin (5HT2c), dopamine (D2 and D3), histamine (H1) [48], and muscarinic (M2 and M3) receptors have been found to raise appetite [49, 50]. Moreover, using endocrine/metabolic mechanisms, antipsychotics are able to directly trigger the hypothalamus–pituitary–adrenal axis activation [51], insulin secretion deficits [52], and gastrointestinal hormones changes [53]. Some other studies proposed a relationship between the antipsychotic drug-induced increased food intake and variations in melatonin, leptin, opioid, and endocannabinoid signaling [54].

As another finding, schizophrenic patients with higher total scores in PANSS were discovered with higher total scores in EAT-26. In other words, the presence of DEBs among schizophrenic patients was related to a more severe expression of active psychotic symptoms. In detail, this finding hypothesized that comorbidity of DEBs was associated with more severe schizophrenia psychopathology. Although there is very little evidence to support this finding, an explanatory model can be obtained from the dopamine hypothesis [55]. In fact, evidence implies that the dopaminergic system is a key mediator of appetitive conditioning [56].

Additionally, anxiety and depression were regarded as a risk factor for a variety of DEBs. On this matter, a recent hypothesis has suggested that DEBs may serve as a method whereby some subjects cope with anxiety and depression. In this regard, cognitive avoidance theory supports the role of anxiety and depression in the DEBs process by suggesting that patients with affective disorders engage in DEBs episodes to escape from this state [12]. The role of tobacco smoking and type 2 diabetes in the development of DEBs was previously discussed as well.

Limitations of the study

This study has suffered some limitations. Firstly, the cross-sectional design avoided the precise understanding of relationships’ nature, especially causality. Next, self-reporting questionnaires cannot confirm a diagnosis, and it usually overestimates the prevalence of DEBs. It is possibly more prominent among schizophrenic patients, who may easily exaggerate or minimize the scorings. These limitations can be markedly resolved by designing longitudinal studies and interviewing individual participants. Thirdly, the results cannot be generalized to other regions since the sample size was limited to a single geographic region with unique individual, social, and cultural characteristics. Therefore, more extensive research needs to be carried out in other regions across the world. The fourth limitation is the absence of a standardized assessment concerning the study of DEBs among schizophrenic patients. EAT-26 has not been designed to make a diagnosis of any FEDs (not even atypical or subthreshold ones). Thus, it should not be used in place of any professional diagnosis as it has low positive predictive value due to denial and social desirability, as well as for the possible confounding role of comorbid factors [57]. So, it hampers an accurate evaluation of the frequency of DEBs.

Conclusions

It is essential to identify DEBs among schizophrenic patients as an important cause of cardiometabolic disorders [6, 22]. Since DEBs occurrence is independent of different phases of schizophrenia, it becomes more critical to evaluate the risk of DEBs during the entire course of schizophrenia. Moreover, the use of psychosocial interventions, treatment of affective disorders (i.e., anxiety and depression), antipsychotic medication switching, treatment of tobacco smoking and type 2 diabetes may reduce the risk of DEBs among schizophrenic patients owing to the association between DEBs and psychosocial rehabilitation, category of antipsychotic medications, anxiety, depression, tobacco smoking, and type 2 diabetes. Additionally, the role of duration of psychosis in the development of DEBs indicated the need for a more precise examination of such behaviors at earlier stages of schizophrenia. Nevertheless, further studies (in particular longitudinal and empirical research) are required to prove the actual roles of the above factors in developing DEBs among schizophrenic patients.

Availability of data and materials

The datasets generated and analyzed during the current study are not publicly available because no consent was obtained from the participants in this regard. However, the data are available from the corresponding author on a reasonable request.

Abbreviations

- ACT:

-

Assertive community treatment

- ANOVA:

-

Analysis of variance

- BAI:

-

Beck Anxiety Inventory

- BDI-II:

-

Beck Depression Inventory

- DEBs:

-

Disordered eating behaviors

- DSM-5:

-

Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, 5th Edition

- EAT-26:

-

The 26-item Eating Attitudes Test

- EAT-40:

-

The 40-item Eating Attitudes Test

- FEDs:

-

Feeding and eating disorders

- GHQ-28:

-

The 28-item General Health Questionnaire

- PANSS:

-

Positive and Negative Syndrome Scale

- SCID-5-RV:

-

Structured Clinical Interviews for DSM-5: Research Version

- SE:

-

Supported employment

- TFEQ:

-

Three-Factor Eating Questionnaire

- WRAP:

-

Wellness recovery action planning

References

Tanofsky-Kraff M, Yanovski SZ. Eating disorder or disordered eating? Non-normative eating patterns in obese individuals. Obes Res. 2004;12(9):1361–6. https://doi.org/10.1038/oby.2004.171.

Gottlieb C. Disordered eating or eating disorder: What’s the difference? More subtle forms of disordered eating can also be dangerous. Eat Disord. 2015;2014(29):449–55.

Yum SY. The starved brain: eating behaviors in schizophrenia. Psychiatr Ann. 2005;35(1):82–9. https://doi.org/10.3928/00485713-20050101-10.

Kraepelin E. Dementia Praecox and Paraphrenia. Edinburgh: Thoemmes Press; 2002. p. 87 (original published 1919).

Bleuler E. Textbook of psychiatry. New York: Macmillan Co; 1924. p. 149 (original published 1911).

Kouidrat Y, Amad A, Lalau JD, Loas G. Eating disorders in schizophrenia: implications for research and management. Schizophr Res Treat. 2014;2014:791573. https://doi.org/10.1155/2014/791573.

Hoff P. Eugen Bleuler’s concept of schizophrenia and its relevance to present-day psychiatry. Neuropsychobiology. 2012;66(1):6–13. https://doi.org/10.1159/000337174.

Yum SY, Hwang MY, Halmi KA. Eating disorders in schizophrenia. Psychiatr. Times. 2006;23(7):10.

Yum SY, Caracci G, Hwang MY. Schizophrenia and eating disorders. Psychiatr Clin North Am. 2009;32(4):809–19. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.psc.2009.09.004.

Foulon C. Schizophrenia and eating disorders. Encephale. 2003;29(5):463–6.

Lundgren JD, Rempfer MV, Brown CE, Goetz J, Hamera E. The prevalence of night eating syndrome and binge eating disorder among overweight and obese individuals with serious mental illness. Psychiatry Res. 2010;175(3):233–6. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.psychres.2008.10.027.

Rosenbaum DL, White KS. The role of anxiety in binge eating behavior: a critical examination of theory and empirical literature. Health Psychol Res. 2013;1(2):e19. https://doi.org/10.4081/hpr.2013.e19.

Bruch H. Eating disorders and schizophrenia. In: Usdin G, editor. Psychoneurosis and schizophrenia. Philadelphia: Lippincott; 1966. p. 113–24.

Kallmann FJ. The genetic theory of schizophrenia: an analysis of 691 schizophrenic twin index families. Am J Psychiatry. 1946;103(3):309–22. https://doi.org/10.1176/ajp.103.3.309.

Fernø J, Varela L, Skrede S, Vázquez MJ, Nogueiras R, Diéguez C, et al. Olanzapine-induced hyperphagia and weight gain associate with orexigenic hypothalamic neuropeptide signaling without concomitant AMPK phosphorylation. PLoS ONE. 2011;6(6):e20571. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0020571.

Sallemi R, Hentati S, Feki I, Masmoudi J, Moala M. Eating disorders in schizophrenia. Eur Psychiatry. 2017;41:S284.

Ryu S, Nam HJ, Oh S, Park T, Lim M, Choi JS, Baek JH, Jang JH, Park HY, Kim SN, Joo YH. Eating-behavior changes associated with antipsychotic medications in patients with schizophrenia as measured by the drug-related eating behavior questionnaire. J Clin Psychopharmacol. 2013;33(1):120–2. https://doi.org/10.1097/JCP.0b013e31827c2e2d.

Blouin M, Tremblay A, Jalbert ME, Venables H, Bouchard RH, Roy MA, et al. Adiposity and eating behaviors in patients under second generation antipsychotics. Obesity. 2008;16(8):1780–7. https://doi.org/10.1038/oby.2008.277.

Brömel T, Blum WF, Ziegler A, Schulz E, Bender M, Fleischhaker C, Remschmidt H, Krieg JC, Hebebrand J. Serum leptin levels increase rapidly after initiation of clozapine therapy. Mol Psychiatry. 1998;3(1):76–80. https://doi.org/10.1038/sj.mp.4000352.

Gebhardt S, Haberhausen M, Krieg JC, Remschmidt H, Heinzel-Gutenbrunner M, Hebebrand J, Theisen FM. Clozapine/olanzapine-induced recurrence or deterioration of binge eating-related eating disorders. J Neural Transm. 2007;114(8):1091–5. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00702-007-0663-2.

Sentissi O, Viala A, Bourdel MC, Kaminski F, Bellisle F, Olié JP, et al. Impact of antipsychotic treatments on the motivation to eat: preliminary results in 153 schizophrenic patients. Int Clin Psychopharmacol. 2009;24(5):257–64. https://doi.org/10.1097/YIC.0b013e32832b6bf6.

Kouidrat Y, Amad A, Stubbs B, Louhou R, Renard N, Diouf M, et al. Disordered eating behaviors as a potential obesogenic factor in schizophrenia. Psychiatry Res. 2018;269:450–4. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.psychres.2018.08.083.

Ayano G. Co-occurring medical and substance use disorders in patients with schizophrenia: a systematic review. Int J Ment Health. 2019;48(1):62–76. https://doi.org/10.1080/00207411.2019.1581047.

Annamalai A, Kosir U, Tek C. Prevalence of obesity and diabetes in patients with schizophrenia. World J Diabetes. 2017;8(8):390–6. https://doi.org/10.4239/wjd.v8.i8.390.

Anzengruber D, Klump KL, Thornton L, Brandt H, Crawford S, Fichter MM, Halmi KA, Johnson C, Kaplan AS, LaVia M, Mitchell J. Smoking in eating disorders. Eat Behav. 2006;7(4):291–9. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.eatbeh.2006.06.005.

García-Mayor RV, García-Soidán FJ. Eating disorders in type 2 diabetic people: brief review. Diabetes Metab Syndrome. 2017;11(3):221–4. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.dsx.2016.08.004.

Burmeister E, Aitken LM. Sample size: How many is enough? Aust Crit Care. 2012;25(4):271–4. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.aucc.2012.07.002.

Gargari BP, Khadem-Haghighian M, Taklifi E, Hamed-Behzad M, Shahraki M. Eating attitudes, self-esteem and social physique anxiety among Iranian females who participate in fitness programs. J Sports Med Phys Fitness. 2010;50(1):79–84.

Kaviani H, Mousavi AS. Psychometric properties of the Persian version of Beck Anxiety Inventory (BAI). Tehran Univ Med J . 2008;66(2):136–40 (Persian).

Ghassemzadeh H, Mojtabai R, Karamghadiri N, Ebrahimkhani N. Psychometric properties of a Persian-language version of the Beck Depression Inventory-Second edition: BDI-II-PERSIAN. Depress Anxiety. 2005;21(4):185–92. https://doi.org/10.1002/da.20070.

Heshmati RM. Exploration of the factor structure of positive and negative syndrome scale in schizophrenia spectrum disorders. J Clin Psychol. 2010;2:6 (Persian).

First MB, Williams JB, Karg RS, Spitzer RL. User’s guide for the SCID-5-CV: structured clinical interview for DSM-5 disorders, clinician version. Arlington: American Psychiatric Association; 2016.

Taghavi S. Validity and reliability of the general health questionnaire (GHQ-28) in college students of Shiraz University. J Psychol. 2002;5(4):381–98 (Persian).

Fawzi MH, Fawzi MM. Disordered eating attitudes in Egyptian antipsychotic naive patients with schizophrenia. Compr Psychiatry. 2012;53(3):259–68. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.comppsych.2011.04.064.

Mukundan A, Faulkner G, Cohn T, Remington G. Antipsychotic switching for people with schizophrenia who have neuroleptic-induced weight or metabolic problems. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2010. https://doi.org/10.1002/14651858.CD006629.pub2.

Essawy HI, Elghonemy SH, Mahmoud DA, Arafa AM. The relationship between disturbed eating behavior and substance abuse in an Egyptian sample. QJM. 2020. https://doi.org/10.1093/qjmed/hcaa054.013.

Khalil RB, Hachem D, Richa S. Eating disorders and schizophrenia in male patients: a review. Eat Weight Disord. 2011;16(3):e150–6. https://doi.org/10.1007/bf03325126.

Hennessy KD, Green-Hennessy S. A review of mental health interventions in SAMHSA’s National Registry of Evidence-Based Programs and Practices. Psychiatr Serv. 2011;62(3):303–5. https://doi.org/10.1176/ps.62.3.pss6203_0303.

Dixon LB, Dickerson F, Bellack AS, Bennett M, Dickinson D, Goldberg RW, et al. The 2009 schizophrenia PORT psychosocial treatment recommendations and summary statements. Schizophr Bull. 2010;36(1):48–70. https://doi.org/10.1093/schbul/sbp115.

Cook JA, Copeland ME, Jonikas JA, Hamilton MM, Razzano LA, Grey DD, et al. Results of a randomized controlled trial of mental illness self-management using Wellness Recovery Action Planning. Schizophr Bull. 2012;38(4):881–91. https://doi.org/10.1093/schbul/sbr012.

American Psychiatric Association. Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders. 5th ed. Arlington, VA: American Psychiatric Publishing; 2013.

Starrenburg FC, Bogers JP. How can antipsychotics cause diabetes mellitus? Insights based on receptor-binding profiles, humoral factors and transporter proteins. Eur Psychiatry. 2009;24(3):164–70. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.eurpsy.2009.01.001.

Weston-Green K, Huang XF, Han M, Deng C. The effects of antipsychotics on the density of cannabinoid receptors in the dorsal vagal complex of rats: implications for olanzapine-induced weight gain. Int J Neuropsychopharmacol. 2008;11(6):827–35. https://doi.org/10.1017/S1461145708008560.

Lett TA, Wallace TJ, Chowdhury NI, Tiwari AK, Kennedy JL, Müller DJ. Pharmacogenetics of antipsychotic-induced weight gain: review and clinical implications. Mol Psychiatry. 2012;17(3):242–66. https://doi.org/10.1038/mp.2011.109.

Reynolds GP, Kirk SL. Metabolic side effects of antipsychotic drug treatment–pharmacological mechanisms. Pharmacol Ther. 2010;125(1):169–79. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.pharmthera.2009.10.010.

Sharpe JK, Stedman TJ, Byrne NM, Wishart C, Hills AP. Energy expenditure and physical activity in clozapine use: implications for weight management. Aust N Z J Psychiatry. 2006;40(9):810–4. https://doi.org/10.1080/j.1440-1614.2006.01888.x.

Sharpe JK, Byrne NM, Stedman TJ, Hills AP. Resting energy expenditure is lower than predicted in people taking atypical antipsychotic medication. J Am Diet Assoc. 2005;105(4):612–5. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jada.2005.01.005.

Kim SF, Huang AS, Snowman AM, Teuscher C, Snyder SH. Antipsychotic drug-induced weight gain mediated by histamine H1 receptor-linked activation of hypothalamic AMP-kinase. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2007;104(9):3456–9. https://doi.org/10.1073/pnas.0611417104.

Coccurello R, Moles A. Potential mechanisms of atypical antipsychotic-induced metabolic derangement: clues for understanding obesity and novel drug design. Pharmacol Ther. 2010;127(3):210–51. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.pharmthera.2010.04.008.

Correll CU, Lencz T, Malhotra AK. Antipsychotic drugs and obesity. Trends Mol Med. 2011;17(2):97–107. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.molmed.2010.10.010.

Baptista T, Zarate J, Joober R, Colasante C, Beaulieu S, Paez X, Hernandez L. Drug induced weight gain, an impediment to successful pharmacotherapy: focus on antipsychotics. Curr Drug Targets. 2004;5(3):279–99. https://doi.org/10.2174/1389450043490514.

Chintoh AF, Mann SW, Lam L, Lam C, Cohn TA, Fletcher PJ, Nobrega JN, Giacca A, Remington G. Insulin resistance and decreased glucose-stimulated insulin secretion after acute olanzapine administration. J Clin Psychopharmacol. 2008;28(5):494–9. https://doi.org/10.1097/JCP.0b013e318184b4c5.

Palik E, Birkas KD, Faludi G, Karadi I, Cseh K. Correlation of serum ghrelin levels with body mass index and carbohydrate metabolism in patients treated with atypical antipsychotics. Diabetes Res Clin Pract. 2005;68:S60–4. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.diabres.2005.03.008.

Nasrallah HA. Atypical antipsychotic-induced metabolic side effects: insights from receptor-binding profiles. Mol Psychiatry. 2008;13(1):27–35. https://doi.org/10.1038/sj.mp.4002066.

Kapur S, Mamo D. Half a century of antipsychotics and still a central role for dopamine D2 receptors. Prog Neuropsychopharmacol Biol Psychiatry. 2003;27(7):1081–90. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.pnpbp.2003.09.004.

Martin-Soelch C, Linthicum J, Ernst M. Appetitive conditioning: neural bases and implications for psychopathology. Neurosci Biobehav Rev. 2007;31(3):426–40. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.neubiorev.2006.11.002.

Garfinkel PE, Newman A. The eating attitudes test: twenty-five years later. Eat Weight Disord. 2001;6(1):1–24. https://doi.org/10.1007/BF03339747.

Acknowledgements

The author hereby thanks the patients, who aided in conducting the present study.

Funding

The author received no specific funding for this work.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

M-KH designed the study, collected the data, conducted the data analysis, drafted the manuscript and interpreted the results. The author read and approved the final manuscript.

Authors’ information

Mohsen Khosravi obtained MD degree in 2012 from Isfahan University of Medical Sciences, Iran; and completed his psychiatry residency training successfully at Zahedan University of Medical Sciences, Iran in 2016. Since 2017, he has been working as assistant professor and clinical psychiatrist at Zahedan University of Medical sciences. He translated “Sims’ Symptoms in the Mind: An Introduction to Descriptive Psychopathology-5th Edition” into Persian in 2018 and also compiled a book for psychiatrists and psychologists entitled “Clinical Interviewing in Psychiatric Disorders: A Practical Approach [Based on DSM-5]” in 2019. He published numerous articles in different international psychiatric journals. His interests are more in the research field of borderline personality disorder and its comorbidities.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

The study was approved by the ethics committee of the Medical Faculty of the ZAUMS Zahedan (IR.ZAUMS.REC.1398.210), and all procedures were in accordance with the latest version of the Declaration of Helsinki. Prior to participation, written informed consent was obtained from all participants and their parents/legal guardians after a comprehensive explanation of the study procedures.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The author declares that he has no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/. The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver (http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/) applies to the data made available in this article, unless otherwise stated in a credit line to the data.

About this article

Cite this article

Khosravi, M. Biopsychosocial factors associated with disordered eating behaviors in schizophrenia. Ann Gen Psychiatry 19, 67 (2020). https://doi.org/10.1186/s12991-020-00314-2

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s12991-020-00314-2