Abstract

Background

About 25–60% of the homeless population is reported to have some form of mental disorder. To our knowledge, there are no studies aimed at the screening, diagnosis, treatment, care, rehabilitation, and support of homeless people with mental, neurologic, and substance use (MNS) disorders in general in Ethiopia. This is the first study of its kind in Africa which was aimed at screening, diagnosis, care, treatment, rehabilitation, and support of homeless individuals with possible MNS disorder.

Methods

Community-based survey was conducted from January to March 2015. Homeless people who had overt and observable psychopathology and positive for screening instruments (SRQ20, ASSIST, and PSQ) were involved in the survey and further assessed for possible diagnosis by structured clinical interview for DSM-IV diagnoses and international diagnostic criteria for seizure disorders for possible involvement in care, treatment, rehabilitation services, support, and training. The Statistical Program for Social Science (SPSS version 20) was used for data entry, clearance, and analyses.

Results

A total of 456 homeless people were involved in the survey. Majority of the participants were male (n = 402; 88.16%). Most of the homeless participants had migrated into Addis Ababa from elsewhere in Ethiopia and Eritrea (62.50%). Mental, neurologic, and substance use disorders resulted to be common problems in the study participants (92.11%; n = 420). Most of the participants with mental, neurologic, and substance use disorders (85.29%; n = 354) had psychotic disorders. Most of those with psychosis had schizophrenia (77.40%; n = 274). Almost all of the participants had a history of substance use (93.20%; n = 425) and about one in ten individuals had substance use disorders (10.54%; n = 48). Most of the participants with substance use disorder had comorbid other mental and neurologic disorders (83.33%; n = 40).

Conclusion and recommendation

Mental, neurologic, and substance use disorders are common (92.11%) among street homeless people in Ethiopia. The development of centers for care, treatment, rehabilitation, and support of homeless people with mental, neurologic, and substance use disorders is warranted. In addition, it is necessary to improve the accessibility of mental health services and promote better integration between mental and primary health care services, as a means to offer a better general care and to possibly prevent homelessness among mentally ill.

Similar content being viewed by others

Background

Homelessness problem is most often caused by multiple and interrelated individual structural depreciation. It leads to maladjustment and creates problems related to issues of social, economic, health, and starvation [1]. Homelessness is defined in various ways; in this study, homelessness indicates only those sleeping in designated shelters or public spaces. Broadly the term can include people living in marginal accommodation, as well as roofless people. Some studies include the former, while in others the definition includes only those sleeping in designated shelters or public spaces. The features of a definition of homelessness that are useful in any locality, however, are the lack of appropriate housing and the social marginalization of the individual [2, 3].

Majority of those people sleeping in designated shelters or public spaces have nationalities of the country of residence but some of them may be immigrants or nationality of other countries. The population of homeless persons is very diverse: it includes representatives from all ethnic groups, the young and the old, women and men, single persons and families, people from both urban and rural environments, and people with physical and/or mental problems [4, 5]. Most of the homeless individuals are between 31 and 50 years of age, are unmarried, and are unemployed [6,7,8,9,10].

Homeless people are more likely than the general population to have mental, neurologic, and substance use disorders. Evidence from different countries indicated that most of the homeless people suffer from mental illnesses such as depression, schizophrenia, substance abuse, psychotic disorders, and personality disorders. The prevalence of these disorders among homeless populations varies from country to country, and the precise cultural, national, psychosocial, and neurobiological determinants of these differences remain unclear. However, trends in mental disorders, homelessness, drug abuse, and crime suggest that Western industrial societies are becoming increasingly harmful to psychological and social well-being [11, 12].

According to different studies, 25–50% of the homeless population is reported to have some form of mental disorder [13,14,15] in high-income countries. This rises to about 60% among those who are street homeless. Severe mental disorders (SMD) and addictive or substance use disorders are the most common conditions among homeless individuals. In a meta-analysis of 29 studies conducted from 1979 to 2005, alcohol and drug dependence are the most common problems in homeless people with a pooled prevalence estimate of 38 and 24%, respectively, followed by psychosis with the pooled prevalence estimate of 13% [16]. Other studies indicated that 20–25% of the homeless population in the United States suffers from some form of severe mental illness. In comparison, only 6% of Americans are severely mentally ill [17]. In addition, in United States, mental illness was the third largest cause of homelessness [17].

As compared to general populations, homeless persons suffer from a high prevalence of physical disease, mental illness, and substance abuse [18,19,20,21,22,23,24,25,26,27,28]. Homelessness is associated with an increased risk of infections such as tuberculosis and human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) disease [29,30,31,32,33,34]. Among the homeless, access to health care is often suboptimal [35,36,37,38,39]. Homeless persons also experience severe poverty and often come from disadvantaged minority communities, factors that are independently associated with poor health [40,41,42,43,44,45].

Evidences from different studies have shown that the presence of mental disorders homeless people increases likelihood that the person spends longer periods as homeless [46], increased risk of mortality from general medical causes, suicide [47,48,49] and drug-related causes [50] and also increases vulnerability of the homeless person, including violent victimization [51] and criminality [52,53,54].

Evidence from studies in China [55], Nigeria [56], and Ethiopia [57] in people with schizophrenia revealed prevalence estimates of homelessness, i.e., 7.8, 4, and 7%, respectively. To our knowledge, there are no studies aimed at the screening, diagnosis, treatment, care, rehabilitation, and support of homeless people with mental, neurologic, and substance use (MNS) disorders in general in Ethiopia. This is the first study of its kind in Ethiopia, probably in Africa which aimed at screening, diagnosis, care, treatment, rehabilitation, and support of homeless individuals with possible MNS disorder. Furthermore, this study was aimed at creating continued rehabilitation, training, and other support for homeless people with MNS disorder in Ethiopia.

Methods

Study setting and design

Community-based survey was conducted from January to March 2015, at Addis Ababa, Ethiopia. Addis Ababa is the capital and largest city of Ethiopia. It has a population of 3,384,569 according to the 2015 population census, with annual growth rate of 3.8%. This number has been increased from the originally published 2,738,248 figure and appears to be still largely underestimated [58, 59]. As a chartered city, Addis Ababa has the status of both a city and a state. It is where the African Union is and its predecessor the OAU was based. It also hosts the headquarters of the United Nations Economic Commission for Africa (ECA) and numerous other continental and international organizations. Addis Ababa is therefore often referred to as “the political capital of Africa” due to its historical, diplomatic, and political significance for the continent [60]. In Ethiopia, particularly in major cities, homelessness is a manifest problem. In Addis Ababa, for example, the city administration estimates the number of homeless individuals to be around 50,000. A total of 456 homeless individuals were participated in the survey.

Study population

A total of 456 homeless people (homelessness) equated with street homelessness (rooflessness) were included in the survey. All homeless people are included from Addis Ababa, Ethiopia.

Sampling procedures

Study participants were included using multistage cluster sampling technique. We randomly selected 30 wards (kebeles) from a total of 98 in Addis Ababa, and everyone within the chosen wards (kebeles) who fulfilled the inclusion criteria was sampled.

Inclusion and exclusion criteria

Homeless people who had overt and observable psychopathology and positive for screening instruments (SRQ20, ASSIST and PSQ) were involved in the survey and further assessed for possible diagnosis by structured clinical interview for DSM-IV diagnoses and international diagnostic criteria for seizure disorders for possible involvement for care, treatment, rehabilitation service, support, and trainings.

Data collection, processing, and analyses

Data were collected by trained psychiatry professionals. The SRQ20, ASSIST, and PSQ were used for screening for possible problems, and Structured Clinical Interview of DSM-IV (SCID) was administered by psychiatry professionals and used to assess mental, neurologic, and substance use disorders. The Statistical Program for Social Science (SPSS version 20) was used for data entry, clearance, and analyses. Sociodemographic and clinical factors (diagnosis, history of alcohol, cannabis, nicotine, and khat abuse or dependence) were analyzed and reported using words, tables, and charts.

Ethical consideration

The survey was led by Amanuel Mental Specialized Hospital and was collaborative work with the Federal Ministry of Health of Ethiopia and Addis Ababa Health Bureau. Ethical approval was obtained from Amanuel Mental Specialized Hospital and Addis Ababa Health bureau Research Ethics Committee (REC). Written informed consent was obtained from each study participant and they were informed about their rights to interrupt the interview at any time. Confidentiality was maintained at all levels of the survey. The survey or research team facilitated admission, in collaboration with the district administration and Amanuel Mental Specialized Hospital, for those who had possible mental, neurologic, and substance use disorders and considered at immediate risk, including admission to a rehabilitation unit. All homeless people with possible mental, neurologic, and substance use disorders were evaluated by a specialist for diagnosis and further management and most of them were treated in inpatient unit at primary-, secondary-, and tertiary-level health institutions for 3–6 months.

Results

Sociodemographic characteristics of participants

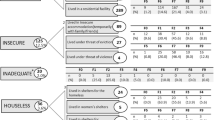

A total of 456 homeless people were involved in the survey. Majority of the participants were male (n = 402; 88.16%). Most of the homeless participants had migrated into Addis Ababa from elsewhere in Ethiopia and Eritrea (62.50%). Most homeless participants were chronically homeless, with over three-fourths (79.61%) having been homeless for 2 years or longer; only 20.39% of participants were homeless for less than 2 years (Table 1).

Magnitude and types of specific disorders among homeless people with mental, neurologic, and substance use disorders

In general, a majority of the participants included in the survey had some form of MNS disorder (92.11%; n = 420), and more than three-fourths of cases (85.29%; n = 354) were psychotic disorders. Most of those with psychosis had schizophrenia (77.40%; n = 274). Almost all of the participants had a history of substance use (93.20%; n = 425) and about one in ten individuals had substance use disorders (10.54%; n = 48). Most of the substance use disorder was comorbid with other mental and neurologic disorders (83.33%; n = 40) (Table 2).

Discussion

The current survey revealed that a significant portion of homeless study participants had mental, neurologic, and substance use disorders and the high burden of mental, neurologic, and substance use disorders among street homeless in Ethiopia. To our knowledge, there are no studies aimed at screening, diagnosis, treatment care, rehabilitation, and establishment of continued support and networks for homeless people with MNS disorder in general in Ethiopia.

This study revealed that the homeless people have very diverse sociodemographic characteristics in Ethiopia; this was comparable to that seen in homeless people in high-income country settings [4, 5]. In this survey majority, the participants had some form of MNS disorder (92.11%; n = 420), and more than three-fourths of cases (85.29%; n = 354) had psychotic disorders. Most of those with psychosis had schizophrenia (77.40%; n = 274). These findings were higher than the findings of Brazil (49%) [61] and other high-income countries (60%) [13]. The possible reason for the higher rate of mental disorder in our survey may be because in our study those who had overt and observable psychopathology and positive by screening instruments were involved, who are known to have higher rates of mental, neurologic, and substance use disorders.

The findings of the current study revealed that most of those homeless people with psychosis had schizophrenia (77.40%; n = 274). This finding was higher than the study done in high-income countries which revealed 20–25% of the homeless population in the United States suffers from some form of severe mental illness including schizophrenia [17]. The possible reason for the higher rate of schizophrenia in our survey may be because in our study those who had overt and observable psychopathology and positive by screening instruments were involved, who are known to have higher rates of mental, neurologic, and substance use disorders.

In addition, we found that one in ten individuals had substance use disorders (10.54%; n = 48). These results are lower than a report from a meta-analysis of 29 studies conducted from 1979 to 2005, which revealed pooled prevalence estimate alcohol and drug dependence, i.e, 38 and 24%, respectively, among homeless individuals [16]. The possible reason for this difference might be due to the instrument they used, socioeconomic and cultural difference, and the sample included in the study.

Limitation of the study

In our study, those who had overt and observable psychopathology and positive by screening instruments were involved, who are known to have higher rates of mental, neurologic and substance use disorders.

Conclusion and recommendations

Mental, neurologic, and substance use disorders resulted to be common problems in the study participants (92.11%; n = 420). Most of the participants with mental, neurologic, and substance use disorders (85.29%; n = 354) had psychotic disorders. Most of those with psychosis had schizophrenia (77.40%; n = 274). Almost all of the participants had a history of substance use (93.20%; n = 425) and about one in ten individuals had substance use disorders (10.54%; n = 48). In the current study, it was found that comorbid substance use disorder with other mental and neurologic disorders was a more frequent phenomenon among homeless people and that majority of those who have mental and neurologic disorders have co-occurring substance use disorders as compared to those who have no mental and neurologic disorders. Our findings indicate that attention needs to be given to screen and assess mental, neurologic, and substance use disorders in homeless people. The development of centers for care, treatment, rehabilitation, and support of homeless people with mental, neurologic, and substance use disorders is warranted. In addition, it is necessary to improve the accessibility of mental health services and promote better integration between mental and primary health care services, as a means to offer a better general care and to possibly prevent homelessness among mentally ill.

References

Kuhn R, Culhane DP. Applying cluster analysis to test a typology of homelessness by pattern of shelter utilization: Results from the analysis of administrative data. American Journal of community psychology. 1998;26(2):207–32.

Scott J. Homelessness and mental illness. Br J Psychiatry. 1993;162:314–24.

Arce AA, Vergare MJ. Identifying and characterizing the mentally ill among the homeless. In: Lamb HR, editor. The homeless mentally ill: a task force report of the American Psychiatric Association. Washington: American Psychiatric Association; 1984. p. 75–89.

Burt MR. Over the edge: the growth of homelessness in the 1980s. New York: Russell Sage Foundation; 1992.

Robertson MJ, Greenblatt M. Homelessness: a national perspective. New York: Plenum Press; 1992.

Brandt P, Munk-Jorgensen P. Homeless in Denmark. In: Bughra D, editor. Homelessness and mental health. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press; 1996. p. 189–96.

Fernandez J. Homelessness: an Irish perspective. In: Bughra D, editor. Homelessness and mental health. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press; 1996. p. 209–29.

Koegel P, Burnam MA, Baumohl J. The causes of homelessness. In: Baumohl J, editor. Homeless in America. New York: Oryx Press; 1996.

O’ Flaherty B. Making room: the economics of homelessness. Cambridge: Harvard University Press; 1996.

Rossler W, Salize HJ. Continental European experience: Germany. In: Bughra D, editor. Homelessness and mental health. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press; 1996. p. 197–208.

Eckersley R. Failing a generation: the impact of culture on the health and well-being of youth. J Paediatr Child Health. 1993;29(Suppl. 1):16–9.

Fazel S, Khosla V, Doll H, Geddes J. The prevalence of mental disorders among the homeless in western countries: systematic review and meta-regression analysis. PLoS Med. 2008;5(12):e225. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pmed.0050225.

Scott J. Homelessness and mental illness. Br J Psychiatry. 1993;162:314–24.

Breakey WR, Fischer PJ, Kramer M. Health and mental health problems of homeless men and women living in Baltimore. JAMA. 1989;262:1352–7.

Gelberg L, Linn LS. Demographic differences in health status of homeless adults. J Gen Intern Med. 1992;7:601–8.

Koegel P, Burnam MA. Alcoholism among homeless adults in the innercity of Los Angeles. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 1988;45:1011–8.

Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration, Center for Mental Health Services. Homelessness. http://mentalhealth.samhsa.gov/cmhs/Homelessness/. Accessed Jun 11, 2009.

Breakey WR, Rischer PJ, Kramer M, et al. Health and mental health problems of homeless men and women in Baltimore. JAMA. 1989;262:1352–7.

Bassuk EL, Rubin L, Lauriat A. Is homelessness a mental health problem? Am J Psychiatry. 1984;141:1546–50.

Koegel P, Burnam A, Farr RK. The prevalence of specific psychiatric disorders among homeless individuals in the inner city of Los Angeles. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 1988;45:1085–92.

Koegel P, Burnam MA. Alcoholism among homeless adults in the inner city of Los Angeles. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 1988;45:1011–8.

Susser E, Struening EL, Conomver S. Psychiatric problems in homeless men. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 1989;46:845–50.

Gelberg L, Linn LS, Usatine RP, Smith MH. Health, homelessness, and poverty: a study of clinic users. Arch Intern Med. 1990;150:2325–30.

Ferenchick GS. Medical problems of homeless and nonhomeless persons attending an inner-city health clinic. Am J Med Sci. 1991;301:379–82.

Fischer PJ, Breakey WR. The epidemiology of alcohol, drug, and mental disorders among homeless persons. Am Psychol. 1991;46:1115–28.

Centers for Disease Control (CDC). Characteristics and risk behaviors of homeless black men seeking services from the community homeless assistance plan—Dade County, Florida, August 1991. MMWR. 1991;40:865–8.

Gelberg L, Linn LS. Demographic differences in health status of homeless adults. J Gen Intern Med. 1992;7:601–8.

Gelberg L, Leake BD. Substance use among impoverished medical patients: the effect of housing status and other factors. Med Care. 1993;31:757–66.

Brudney K, Dobkin J. Resurgent tuberculosis in New York City. Am Rev Respir Dis. 1991;144:745–9.

Concato J, Rom WN. Endemic tuberculosis among homeless men in New York City. Arch Intern Med. 1994;154:2069–73.

Barnes PF, El-Hajj H, Preston-Martin S, et al. Transmission of tuberculosis among the urban homeless. JAMA. 1996;275:305–7.

Torres RA, Mani S, Altholz J, Brickner PW. Human immunodeficiency virus infection among homeless men in a New York City shelter. Arch Intern Med. 1990;150:2030–5.

Allen DM, Lehman JS, Green TA, et al. HIV infection among homeless adults and runaway youth, United States, 1989–1992. AIDS. 1994;8:1593–8.

Zolopa AR, Hahn JA, Gorter R, et al. HIV and tuberculosis infection in San Francisco’s homeless adults. JAMA. 1994;272:455–61.

Elvy A. Access to care. In: Brickner PW, Scharer LK, Conanan B, et al., editors. Health care of homeless people. New York: Springer Publishing Co; 1985. p. 223–31.

Brickner PW, Scanlan BC, Conanan B, et al. Homeless persons and health care. Ann Intern Med. 1986;104:405–9.

Robertson MJ, Cousineau MR. Health status and access to health services among the urban homeless. Am J Public Health. 1986;76:561–3.

Stark LR. Barriers to health care for homeless people. In: Jahiel RI, editor. Homelessness: a prevention oriented approach. Baltimore: Johns Hopkins University Press; 1992. p. 151–64.

Gelberg L, Gallagher TC, Andersen RM. KoegelP. Competing priorities as a barrier to medical care among homeless adults in Los Angeles. Am J Public Health. 1997;87:217–20.

Fein O. The influence of social class on health status. J Gen Intern Med. 1995;10:577–86.

Bucher HC, Ragland DR. Socioeconomic indicators and mortality from coronary heart disease and cancer. Am J Public Health. 1995;85:1231–6.

McDonough P, Duncan GJ, Williams D, House J. Income dynamics and adult mortality in the United States, 1972 through 1989. Am J Public Health. 1997;87:1476–83.

Lantz PM, House JS, Lepkowski JM, et al. Socioeconomic factors, health behaviors, and mortality. JAMA. 1998;279:1703–8.

Geronimus AT, Bound J, Waidmann TA, et al. Excess mortality among blacks and whites in the United States. N Engl J Med. 1996;335:1552–8.

Singh GK, Yu SM. Trends and differentials in adolescent and young adult mortality in the United States, 1950 through 1993. American Journal of Public Health. 1996;86(4):560–4.

Morse G, Shields NM, Hanneke CR, McCall GJ, Calsyn RJ, Nelson B. St. Louis’ homeless: mental health needs, services, and policy implications. Psychosoc Rehabil J. 1986;9:39–50.

Babidge NC, Buhrich N, Butler T. Mortality among homeless people with schizophrenia in Sydney, Australia: a 10 year follow-up. Acta Psychiatr Scand. 2001;103:105–10.

Hwang SW. Mortality among men using homeless shelters in Toronto, Ontario. JAMA. 2000;283:2152–7.

Prigerson HG, Desai RA, Liu-Mares W, Rosenheck RA. Suicidal ideation and suicide attempts in homeless mentally ill persons: age-specific risks of substance abuse. Soc Psychiatry Psychiatr Epidemiol. 2003;38:213–9.

Barrow SM, Herman DB, Cordova P, Struening EL. Mortality among homeless shelter residents in New York City. Am J Public Health. 1999;89:529–34.

Walsh E, Moran P, Scott C, McKenzie K, Burns T, Creed F, Tyrer P, Murray RM, Fahy T. Prevalence of violent victimisation in severe mental illness. Br J Psychiatry. 2003;183:233–8.

Brennan P, Mednick S, Hodgins S. Major mental disorders and criminal violence in a Danish birth cohort. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2000;57:494–500.

Fazel S, Grann M. The population impact of severe mental illness on violent crime. Am J Psychiatry. 2006;163:1397–403.

Gelberg L, Linn LS, Leake BD. Mental health, alcohol and drug use, and criminal history among homeless adults. Am J Psychiatry. 1988;145:191–6.

Ran MS, Chan CLW, Chen EYH, Xiang MZ, Caine ED, Conwell Y. Homelessness among patients with schizophrenia in rural China: a 10-year cohort study. Acta Psychiatr Scand. 2006;114:118–23.

Gureje O, Bamidele R. Thirteen-year social outcome among Nigerian outpatients with schizophrenia. Soc Psychiatry Psychiatr Epidemiol. 1999;34:147–51.

Kebede D, Alem A, Shibre T, Negash A, Fekadu A, Fekadu D, Deyassa N, Jacobsson L, Kullgren G. Onset and clinical course of schizophrenia in Butajira-Ethiopia—a community-based study. Soc Psychiatry Psychiatr Epidemiol. 2003;38:625–31.

Central Statistical Agency of Ethiopia. “Census 2007, preliminary (pdf-file)” (PDF). Archived (PDF) from the original on 18 December 2008. Retrieved 7 Dec 2008.

Givental E. Addis Ababa Urbanism: Indigenous Urban Legacies and Contemporary Challenges. J Geography Geology. 2017;9(1):25.

“United Nations Economic Commission for Africa”. UNECA. Accessed 5 May 2012.

Lovisi GM, Mann AH, Coutinho E, Morgado AF. Mental illness in an adult sample admitted to public hostels in the Rio de Janeiro metropolitan area. Braz Soc Psychiatry Psychiatr Epidemiol. 2003;38:496–501.

Authors’ contributions

GA conceived the study and was involved in the study design, reviewed the article, analysis, report writing, and drafted the manuscript, DA, KH, AC, ZY, HS, MA, BT, KH, MS, SD, and LB were involved in the study design and analysis and drafted the manuscript. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Acknowledgements

The authors acknowledge the Federal Ministry of Health, Ethiopia for funding the study. The authors appreciate the study participants for their cooperation in providing the necessary information.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Consent for publication

Not applicable

Ethics approval and consent to participate

Ethical approval was obtained from Amanuel Mental Specialized Hospital and Addis Ababa Health bureau Research Ethics Committee (REC). Confidentiality was maintained at all levels of the survey. The survey or research team facilitated admission, in collaboration with the district administration and Amanuel Hospital, for those who had possible mental, neurologic, and substance use disorders and considered at immediate risk, including admission to a rehabilitation unit. All homeless people with possible mental, neurologic, and substance use disorders were evaluated by specialist for diagnosis and further management and most of them were treated at inpatient unit at primary-, secondary-, and tertiary-level health institutions for 3–6 months.

Funding

This research work is funded by the Federal Ministry of Health of Ethiopia.

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made. The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver (http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/) applies to the data made available in this article, unless otherwise stated.

About this article

Cite this article

Ayano, G., Assefa, D., Haile, K. et al. Mental, neurologic, and substance use (MNS) disorders among street homeless people in Ethiopia. Ann Gen Psychiatry 16, 40 (2017). https://doi.org/10.1186/s12991-017-0163-1

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s12991-017-0163-1