Abstract

Background

Persistent human papillomavirus (HPV) infection is a key factor for the development and progression of cervical cancer. We sought to identify the type-specific HPV prevalence by cervical cytology and assess disease progression risk based on high-risk persistent HPV infection in South Korea.

Methods

To investigate the HPV prevalence by Pap results, we searched seven literature databases without any language or date restrictions until July 17, 2019. To estimate the risk of disease progression by HPV type, we used the Korea HPV Cohort study data. The search included the terms “HPV” and “Genotype” and “Korea.” Studies on Korean women, type-specific HPV distribution by cytological findings, and detailed methodological description of the detection assay were included. We assessed the risk of disease progression according to the high-risk HPV type related to the nonavalent vaccine and associated persistent infections in 686 HPV-positive women with atypical squamous cells of uncertain significance or low-grade squamous intraepithelial lesions from the Korea HPV Cohort Study. Type-specific HPV prevalence was the proportion of women positive for a specific HPV genotype among all HPV-positive women tested for that genotype in the systematic review.

Results

We included 23 studies in our review. HPV-16 was the most prevalent, followed by HPV-58, -53, -70, -18, and -68. In women with high-grade squamous intraepithelial lesions, including cancer, HPV-16, -18, and -58 were the most prevalent. In the longitudinal cohort study, the adjusted hazard ratio of disease progression from atypical squamous cells of uncertain significance to high-grade squamous intraepithelial lesions was significantly higher among those with persistent HPV-58 (increase in risk: 3.54–5.84) and HPV-16 (2.64–5.04) infections.

Conclusions

While HPV-16 was the most prevalent, persistent infections of HPV-16/58 increased the risk of disease progression to high-grade squamous intraepithelial lesions. Therefore, persistent infections of HPV-16 and -58 are critical risk factors for cervical disease progression in Korea. Our results suggest that equal attention should be paid to HPV-58 and -16 infections and provide important evidence to assist in planning the National Immunization Program in Korea.

Similar content being viewed by others

Background

Human papillomavirus (HPV) infection is the main cause of cervical cancer. Particularly, HPV type 16 (HPV-16) and HPV-18 cause 70% of cervical cancers and pre-cancerous cervical lesions [1, 2]. Approximately 570,000 cases of cervical cancer and 311,000 deaths from the disease were reported in 2018 [3]. In Korea, the incidence of cervical cancer has been steadily decreasing from 4,443 cases in 1999 (18.9 per 100,000) to 3,500 cases in 2018 (10.5 per 100,000); however, it remains the eighth most common cancer affecting women [4].

Most human papillomavirus (HPV) infections regress spontaneously, whereas 10–15% of them may progress to precancerous lesions and then cancer with persistent HPV infections. Persistent high-risk HPV (HR-HPV) infection is strongly and consistently associated with high-grade cervical lesions and causes cervical cancer progression in more than 99.7% of women [5, 6]. According to the most updated International Agency for Research on Cancer information, the prevalence of HPV infections is 68.0% in cervical cancer (6.3% in cervical lesions with normal cytology, 33.2% in low-grade lesions, and 46.7% in high-grade lesions) among the Korean population [7, 8].

Type-specific HPV prevalence varies in different countries. Globally, HPV-16, -31, -51, and -53 are the most prevalent HPV genotypes. HPV-33 is prevalent in Europe, while HPV-52 and -58 are predominant in Asia [9, 10]. HPV-16, which is globally the most common cause of HPV-associated cancers, is also the most common type seen in Korea. Moreover, in Korea, HPV-53, -58, and -52 are the other most common HR‐HPV types detected [11, 12]. Infection by a specific type of HPV is a major risk factor in the development of cervical diseases. The prevalence of different HPV types in cervical lesions has been studied extensively.

More recently, a short-term follow-up evaluation of the Korea HPV Cohort Study showed differences in the progression risk for abnormal cervical lesions associated with specific HPV types. The rate of progression from atypical squamous cells of uncertain significance (ASCUS) to low-grade or high-grade squamous intraepithelial lesions (LSIL or HSIL) and from LSIL to HSIL was generally 15% [11]. In comparison, it was significantly higher in HPV-16-positive women than in those positive for other HPV types (27% vs. 17%) [13]. Additionally, with abnormal cervical cytology and positivity for HR-HPV types, the rate of progression to CIN3 or cancer was 7.6% [11, 13, 14].

To date, three prophylactic vaccines target various HR-HPV types, including the bivalent (HPV-16/-18), quadrivalent (HPV-6/-11/-16/-18), and the nonavalent (HPV-6/-11/-16/-18/-31/-33/-45/-52/-58) vaccines. In 2016, the bivalent and quadrivalent HPV vaccines were included as part of the National Immunization Program (NIP) to vaccinate girls aged 12 years in Korea. A significant increase in the awareness of HPV infection (35.8%) and vaccination (36.9%) was observed in 2016 from 13.3 to 8.6% in 2007 [15]. It has been already 6 years since free HPV vaccination offered by NIP in Korea. But, there is still lack of clear understanding of HPV and NIP covered HPV vaccines in the public general [16].

Objective

This study sought to estimate the prevalence of HR-HPV and low-risk (LR)-HPV types in abnormal cervical lesions among Korean women using a systematic review of the literature. Based on the results, we analyzed the data from a 3-year follow-up to determine the disease progression in cases with persistent HR-HPV infections by genotypes related to the nonavalent vaccine. The goal was to assess the risk of progression associated with specific HR-HPV types in persistently infected women with ASCUS or LSIL using data from the Korea HPV Cohort Study from 2010 to 2019.

Methods

Systematic review

Eligibility criteria, information sources, search strategy

We followed the PRISMA guidelines for this systematic review. The study was designed using the PICO strategy as follows: P: patients who underwent cervical screening; I: intervention was HPV genotyping and cervical cytology test; C: comparator was pooled HPV type; and O: outcome was type-specific HPV prevalence based on Papanicolaou (Pap) test. We searched three international (EMBASE [Elsevier], PubMed, and Cochrane library) and four Korean (Korean Studies Information Service System, Korean Medical Database, KoreaMed [a service of the Korean Association of Medical Journal Editors], and National Digital Science Library) literature databases without any language or date restrictions. The search contained a combination of terms including “Human papillomavirus (HPV)” and “Genotype” and “Korea.” All reference lists of the articles were accessed by July 17, 2019, from the databases. Duplicate citations were removed.

Study selection

Studies on (1) Korean women, (2) type-specific HPV distribution by cytological findings, and (3) detailed methodological description of the detection assay were included in the analysis. Finally, full-text copies of potentially relevant papers were obtained.

Data extraction and assessment of the risk of bias

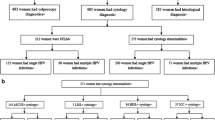

Three independent investigators extracted data from the selected articles to minimize the risk of bias, and discrepancies were resolved by forced consensus. Based on the above criteria, two reviewers independently reviewed the full texts for data abstraction, including the following information from each study: first author, year of publication, study design, case, age, genotyping assay, detected HPV types, and cervical cytology by Pap test when available (Additional file 1: Table S1). A total of 577 citations were retrieved, and 151 full articles were reviewed. Finally, 23 studies were included in the analysis (Fig. 1).

Based on diagnosis by cytology, cervical lesions were classified into five grades: (1) normal, (2) ASCUS+ (including ASCUS, atypical glandular cells of undetermined significance; AGUS, atypical squamous cells without excluding HSIL; ASC-H), (3) LSIL, (4) HSIL, and (5) HSIL+ (including carcinoma in situ, invasive cervical cancer, squamous cell carcinoma, adenocarcinoma, adenocarcinoma in situ, and cervical cancer). HPV-16, -18, -26, -31, -33, -35, -39, -45, -51, -52, -53, -56, -58, -59, -66, -68, -72, and -82 were considered HR-HPV genotypes, while HPV-6, -11, -40, -42, -43, -44, -54, -61, -70, -72, and -81 were considered LR-HPV genotypes [2].

Data synthesis

Type-specific HPV prevalence was defined as the proportion of women positive for a specific HPV genotype among all HPV-positive women tested for that genotype [(number of type-specific HPV-positive women/total number of women tested) * 100]. The overall type-specific HPV prevalence was calculated using the sum of all types based on Pap results. For type-specific HPV prevalence, only studies that tested for a particular HPV type contributed to the analysis of that type; therefore, sample sizes differed between the type-specific analyses. Multiple HPV infections were separated into constituent types; thus, type-specific prevalence represents both single and multiple infections as previously defined [17].

The Korea HPV cohort study

Cohort design

The Korea HPV Cohort Study has been in operation since 2010. It is a multicenter study funded by the Korea Disease Control and Prevention Agency. It was conducted at the obstetrics departments of six general hospitals across Korea to identify high-risk factors for cervical disease progression (until the stage of HSIL) among HPV-infected adult Korean women. This cohort registered participants who met the following inclusion criteria: (1) Korean women aged 20–60 years with a DNA test positive for HPV regardless of its genotype, and (2) diagnosed with ASCUS or LSIL by a Pap test. All participants provided written informed consent. All six hospitals obtained approval from their respective Institutional Review Board (IRB) to participate in the Korea HPV Cohort Study. The enrolled patients underwent HPV DNA typing and cytological examination every 6 months, and an electronic case report form was completed each time [18].

Analysis of disease progression to HSIL

Between 2010 and 2019, of the 1709 registered HPV-positive women in the Korea HPV Cohort Study, 686 with (1) the HR-HPV type related to the nonavalent vaccine or (2) LR-HPV with ASCUS or LSIL were selected to be examined for the risk of disease progression to HSIL. Of the 686 selected women, 335 presented persistent infections of a genotype related to the nonavalent vaccine. Finally, we evaluated the risk of 57 women whose disease had progressed to HSIL within 36 months (Fig. 2). To confirm the potential risk of the HPV type at baseline, we examined the risk of disease progression to HSIL. Additionally, we estimated the risk of disease progression based on the type-specific HPV persistent infections. The characteristics of the women in the Korea HPV Cohort Study are shown in Additional file 2: Table S2.

We used HSIL as our primary endpoint since HSIL was the treatment threshold in the Korea HPV Cohort Study. For disease progression from ASCUS or LSIL to HSIL, all time-to-event analyses were performed from the index visit date to the date when a cytological transition to HSIL was first detected. Women who either dropped out of the study or experienced disease progression after 36 months were censored at the time of their last recorded visit. A persistent type-specific HPV infection was defined as one that was detected at two or more consecutive examinations during disease progression after HPV genotyping at baseline. Multiple HPV infections were separated into their constituent types. The risk of progression to HSIL was estimated using the Kaplan–Meier method and compared using the log-rank test. The Cox regression model was used for statistical adjustments. The hazard ratio and 95% confidence interval (95% CI) were calculated. The women’s ages and HPV genotypes were included in the multivariate model for adjustments. The analysis was conducted using SAS 9.4 (SAS Institute Inc., Cary, NC, USA) and R version 4.0.0 (www.r-project.org). A P value of < 0.05 was considered statistically significant. We obtained approval from the Korea Disease Control and Prevention Agency IRB for this study (approved no. 2018-06-02-P-A).

Results

Systematic review

Study selection

This systematic review included 23 studies that met the eligibility criteria. According to the cervical cytology, 17, 18, 17, 14, and 13 studies described cases with normal cytology, ASCUS+, LSIL, HSIL, and HSIL+, respectively [13, 19,20,21,22,23,24,25,26,27,28,29,30,31,32,33,34,35,36,37,38,39,40].

Type-specific HPV prevalence by cervical cytology

In this study, HPV-16, -58, -53, -70, -18, and -68 were the six most prevalent genotypes, and HPV-16 was the most prevalent (19.4%) among HPV-infected women. In cases with normal cytology, HPV-16 (13.8%) was the most common followed by HPV-53 (13.1%), -70 (10.6%), -58 (10.1%), and -52 (9.8%). In cases with HSIL cytology, HPV-16 was the most common type (35.3%) followed by HPV-58 (17.0%) and HPV-52 (9.0%). In cases with HSIL+ including cancer, HPV-16 was the most prevalent (54.2%), followed by HPV-18 (10.5%) and HPV-58 (7.6%). While the prevalence of HPV-68 was 9.1% in cases with normal cytology, it gradually decreased to 0.8% as the disease progressed to HSIL+ (Table 1).

The Korea HPV cohort study

Risk of disease progression by HPV type

During the follow-up period, the disease progressed to HSIL in 105 out of 686 women. The probability of ASCUS progression (at baseline) to HSIL within 36 months was 17.6% (60 out of 441 women; 95% CI = 13.3–21.7). In the type-specific analysis, after adjusting for age and genotype, using the LR-HPV-infected women as the control group, the aHR (adjusted hazard ratio) for disease progression to HSIL was significantly higher for HPV-16 (aHR = 2.64; 95% CI = 1.18–5.90), HPV-31 (aHR = 3.96; 1.43–10.94), and HPV-58 (aHR = 3.54; 1.66–7.55). Depending on the type-specific HPV persistent infection, the probability of disease progression increased from 17.6 to 30.7%. The highest risk of disease progression was seen with persistent HPV-58 infection (aHR = 5.84; 1.83–18.67), followed by persistent HPV-16 infection (aHR = 5.04; 1.40–18.11) (Table 2).

In women with LSIL at baseline (n = 245), the probability of progression to HSIL within 36 months was 25.7% (95% CI = 18.3–32.3). Compared to the LR-HPV group, the risk of disease progression was highest for HPV-16 (aHR = 4.71; 2.02–11.02), followed by HPV-58 (aHR = 4.37; 1.84–10.41), HPV-33 (aHR = 4.17; 1.25–13.94), and HPV-52 (aHR = 3.42; 1.23–9.52). In women with LSIL and type-specific persistent infections, the probability of disease progression increased to 38.8%. Using the LR-HPV persistently infected women as the control group, those with HPV-33 (aHR = 4.56; 1.16–18.04), -16 (aHR = 4.24; 1.49–12.10), and -58 (aHR = 4.18; 1.54–11.33) were found to be at a significantly higher risk of disease progression (Table 3). We found no association between the age or type of infection (single/multiple) and disease progression in this study.

As shown in Tables 2 and 3, in 182 women with persistent HR-HPV infections, who were characterized by ASCUS or LSIL cytology, HPV-16 (n = 42, 23.1% of HR persistent infection), -52 (n = 46, 25.3% of HR persistent infection), and -58 (n = 53, 29.1% of HR persistent infection) were found to be the most prevalent HR-HPV strains. Furthermore, the estimated progression time (to HSIL) was 19 months for 49 lesions. The median time needed for progression was 18.9, 17.9, and 12.4 months for HPV-16, -18, and -52, respectively. HR-HPVs related to HPV-16, including HPV-31, -33, and -58, required approximately 20 months. HPV-58 was an HR genotype with a high probability of progressing to HSIL within 36 months in cases with ASCUS (61.7%) and LSIL (50.3%).

From data on persistent HPV infections, we graphed the cumulative risk of disease progression to HSIL during 36 months of follow-up after the baseline infection using the Kaplan–Meier survival method. The cumulative probability of progression to HSIL from ASCUS or LSIL was 30.7% (95% CI = 14.6–43.7) and 38.8% (22.4–51.7), respectively. The survival curve was significantly different depending on the baseline cytology (log-rank test; P = 0.042) (Fig. 3a). We also analyzed the cumulative risk of disease progression according to the type-specific persistent infection based on baseline cytology. In women with ASCUS at baseline, the cumulative risk of HPV-58, -16, and LR-HPV was 61.7% (6.1–84.4), 29.2% (5.2–47.1), and 6.6% (0.0–12.9), respectively (log-rank test; P = 0.0044) (Fig. 3b). In contrast, in women with LSIL at baseline, the disease progression risks for HPV-16, -33- 52, and LR-HPV were 66.6% (20.5–85.9), 70.0% (0.0–93.7), and 50.3% (17.0–70.3), respectively (Fig. 3c).

Cumulative risk of disease progression to HSIL within 36 months. Shown is the cumulative risk of disease progression a overall, b from ASCUS to HSIL by HPV genotype, and c from LSIL to HSIL by HPV genotype. A Kaplan–Meier plot was used to estimate the cumulative risk of disease progression to HSIL within 36 months. Shown is the cumulative risk of disease progression a by cervical cytology at baseline, b from ASCUS to HSIL by HPV persistent infection, and c from LSIL to HSIL by HPV persistent infection. Results in Fig. 3b and c represent only significant HPV genotypes in the multivariate analysis. P value was calculated by a log-rank test. ASCUS: Atypical squamous cells of uncertain significance; HSIL: High- grade squamous intraepithelial lesion; LSIL: Low-grade squamous intraepithelial lesion; HPV: human papillomavirus

Discussion

Main findings

We first performed a systematic review to analyze the prevalence of clinically relevant HPV types in Korea. We also determined the progression risk based on type-specific persistent infections in women with ASCUS or LSIL using data from a prospective cohort study in Korea. We found that HPV-16, -58, -53, -52, and -18 were the prevalent HPV types based on clinical cervical cytology. HPV-16 was the dominant genotype, with an overall prevalence of 19.4%. It was the most predominant type in patients with HSIL and worse (HSIL+). Although the prevalence of HPV-18 was lower than that of HPV-53 and HPV-58, it was dominant in HSIL+ patients. In cases with HSIL+, the most prevalent genotypes were HPV-16, -18, and -58. In this review, which was conducted using a systematic analysis of the prevalence of HPV types in cervical lesions, HPV-58, which is included in the nonavalent vaccine, was frequently found in lesions with normal cytology (10.1%), ASCUS (11.4%), LSIL (11.0%), HSIL (17.0%), and HSIL+ (7.6%). Thus, more attention should be paid to HPV-50s infections, especially HPV-58.

Furthermore, based on the 3-year observational cohort, we found that while the risk of persistent infection by HPV-16 was 5.04, it was 5.84 by HPV-58, suggesting that in addition to HPV-16 and HPV-18, vaccines against HPV-52 and HPV-58 will also be beneficial for Korean women.

Strengths and limitations

We investigated the HPV prevalence by Pap results and the risk of disease progression by persistent HPV types. Hence, we used two methodologies: a systematic review and a prospective cohort analysis. Our study's major strength is that it combines and summarizes the results of independent case–control studies and a 3-year follow-up cohort.

Our systematic review has some limitations. First, as this study included HPV-positive Korean women, the results cannot be generalized to other populations. Second, due to the non-standardized HPV typing and Pap testing methods used across the studies, the results might be biased. Third, we did not conduct meta-analysis because of the differences in study setting, participants, and detection assay methods.

There were also several limitations in the longitudinal cohort study. First, because the Korea HPV Cohort Study aimed to investigate HPV infections in women with ASCUS or LSIL, we could not include HPV-negative women or women with normal cytology as a control group. Therefore, assessing the risk of progression of persistent LR-HPV infections was not possible. Second, since women diagnosed with CIN II+ or HSIL were treated by conization during the follow-up period of the Korea HPV Cohort Study, we could not include women with HSIL+. Finally, our study lacked a sufficient sample size. Had the study population been larger, we could have potentially revealed a more significant risk of disease progression by HPV genotype.

Comparison with existing literature

In the systematic review, we found that HPV-16, -58, -53, -52, and -18 were the prevalent HPV types based on clinical cervical cytology. It was known that the distribution of HPV type varies by region. HPV-16, -52, and -56 were prevalent in European region, HPV-53, -62, and -58 were prevalent in South American region, and HPV-16, -58, and -82 were prevalent in Eastern Mediterranean region [41]. Compared with other Asian countries, Korea has a higher prevalence of HPV-53 and -58 and incidence of cervical cancer associated with HPV-52 and -58 [42]. Although, HPV-45 which is most closely related to HPV-18, is an HR oncogenic genotype in sub-Saharan Africa [10], it seems to be less influenced in the Korean population (1.9%). HPV-66 and -68 showed a higher prevalence in normal and low-grade cervical lesions, decreasing with disease progression. These results indicate that a cervix disease is closely related to the HPV type, and its genotype distribution differs regionally.

In our prospective study, the highest risk for disease progression to HSIL was noted with persistent HPV-58 and HPV-16 infections. In the clinical trial, risk of disease progression associated with persistent infection of the same type was significantly higher for oncogenic types than for non-oncogenic types. Hazard ratios for progression of CIN2+ to HPV-16, -33, 31, 45, and -18 were 10.4, 9.6, 5.6, 5.3, and 3.8, respectively [43].

Some studies point to an association between multiple types of HPV and persistent infections [42, 44, 45]. Compared to a single infection, multiple HR-HPV infections place an individual at a higher risk of developing cervical cancer. However, there is no general agreement on this. Consistent with the results of previous studies [46], we found no significant increase in the risk of disease progression with multiple persistent infections (P = 0.986) (Additional file 3: Table S3). We also found that age had no significant effect on the risk of disease progression.

Conclusions

We assessed the association between disease progression and persistent HR-HPV infection with the nonavalent vaccine-related genotypes. Particularly, we found that the risk of disease progression from ASCUS to HSIL was higher with persistent HPV-58 and HPV-16 infections. Therefore, equal attention should be paid to these two genotypes. However, regardless of persistent infections, patients going from LSIL to HSIL did not show differences in disease progression risk. Because ASCUS was regarded as the relatively initial stage based on cytology, it appears that persistent infections of HR-HPV types can affect disease progression from ASCUS to HSIL. We believe that our findings will provide scientific data to assist in detailed planning for the HPV NIP. Further studies with a larger sample size and longer follow-up periods are required to understand better the role of HPV and vaccination in cancer development.

In 2016, Korea initiated bivalent and quadrivalent vaccines as a part of the NIP to vaccinate girls aged 12 years. Both the vaccines are preventive against the HPV-16/18 genotypes that cause 70% of cervical cancers. Knowing the prevalence and genotypes of HPV in a vaccinated population is critical for monitoring the vaccines' efficacy; however, there is no official data on the HPV vaccination in Korean adult women. We recently reported the status of HPV vaccination and its effectiveness in HPV-infected women aged 20–60 years with an HPV vaccine history in Korea. In 1300 women, the prevalence ratio of HPV-16/18 in the 335 vaccinated women (greater than 12 months beforehand) was 0.51 (95% CI = 0.29–0.88) compared with that in the unvaccinated women, which was significant, thereby indicating the positive impact of vaccination [47].

In conclusion, persistent infection of not only HPV-16 but also HPV-58 is a critical risk factor for the progression of cervical disease in Korea. Persistent infections by HR-HPV genotypes, including those in the nonavalent vaccine, provide clues regarding disease progression to HSIL/HSIL+. In this 36-month longitudinal study, we found that the risk of progression in patients with persistent infections varied considerably depending on HR genotypes. We believe that our findings will provide scientific data to assist the detailed planning for the National Immunization Program for HPV.

Availability of data and materials

The datasets supporting the conclusions of this article are included within the article and its additional file.

Abbreviations

- HPV:

-

Human papilloma virus

- HR-HPV:

-

High-risk HPV

- LR-HPV:

-

Low-risk HPV

- ASCUS:

-

Atypical squamous cells of uncertain significance

- LSIL:

-

Low-grade squamous intraepithelial lesions

- HSIL:

-

High-grade SIL

- NIP:

-

National immunization program

- IRB:

-

Institutional review board

- CI:

-

Confidence interval

- aHR:

-

adjusted Hazards ratio

- pap:

-

Papanicolaou

References

de Martel C, Plummer M, Vignat J, Franceschi S. Worldwide burden of cancer attributable to HPV by site, country and HPV type. Int J Cancer. 2017;141:664–70.

Muñoz N, Bosch FX, de Sanjosé S, Herrero R, Castellsagué X, Shah KV, et al. Epidemiologic classification of human papillomavirus types associated with cervical cancer. N Engl J Med. 2003;348:518–27.

Arbyn M, Weiderpass E, Bruni L, de Sanjosé S, Saraiya M, Ferlay J, Bray F. Estimates of incidence and mortality of cervical cancer in 2018: a worldwide analysis. Lancet Glob Health. 2020;8:e191-203.

Korea Central Cancer Registry, National Cancer Center. Annual report of cancer statistics in Korea in 2018, Ministry of Health and Welfare, 2020.

Vintermyr OK, Andersland MS, Bjørge T, Skar R, Iversen OE, Nygård M, Haugland HK. Human papillomavirus type specific risk of progression and remission during long-term follow-up of equivocal and low-grade HPV-positive cervical smears. Int J Cancer. 2018;143:851–60.

Graham SV. The human papillomavirus replication cycle, and its links to cancer progression: a comprehensive review. Clin Sci (Lond). 2017;131:2201–21.

WHO Global Cancer Observatory [Internet]. [cited 2019] https://gco.iarc.fr/.

Kim YT, Serrano B, Lee JK, Lee H, Lee SW, Freeman C, et al. Burden of human papillomavirus (HPV)-related disease and potential impact of HPV vaccines in the Republic of Korea. Papillomavirus Res. 2019;7:26–42.

Vonsky M, Shabaeva M, Runov A, Lebedeva N, Chowdhury S, Palefsky JM, Isaguliants M. Carcinogenesis associated with human papillomavirus infection. Mechanisms and potential for immunotherapy Biochemistry (Mosc). 2019;84:782–99.

Araldi RP, Sant’Ana TA, Módolo DG, de Melo TC, Spadacci-Morena DD, de Cassia Stocco R, et al. The human papillomavirus (HPV)-related cancer biology: an overview. Biomed Pharmacother 2018;106:1537–56.

So KA, Kim MJ, Lee KH, Lee IH, Kim MK, Lee YK, et al. The impact of high-risk HPV genotypes other than HPV 16/18 on the natural course of abnormal cervical cytology: a Korean HPV cohort study. Cancer Res Treat. 2016;48:1313–20.

Ouh YT, Min KJ, Cho HW, Ki M, Oh JK, Shin SY, et al. Prevalence of human papillomavirus genotypes and precancerous cervical lesions in a screening population in the Republic of Korea, 2014–2016. J Gynecol Oncol 2018;29:e14.

So KA, Kim SA, Lee YK, Lee IH, Lee KH, Rhee JE, et al. Risk factors for cytological progression in HPV 16 infected women with ASC-US or LSIL: the Korean HPV cohort. Obstet Gynecol Sci. 2018;61:662–8.

Pretorius RG, Peterson P, Azizi F, Burchette RJ. Subsequent risk and presentation of cervical intraepithelial neoplasia (CIN) 3 or cancer after a colposcopic diagnosis of CIN 1 or less. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2006;195:1260–5.

Oh JK, Jeong BY, Yun EH, Lim MK. Awareness of and attitudes toward human papillomavirus vaccination among adults in Korea: 9-year changes in nationwide surveys. Cancer Res Treat. 2018;50:436–44.

Lee KE. Issues on current HPV vaccination in Korea and proposal statement. Korean J Women Health Nurs. 2019;25:359–64.

Ogembo RK, Gona PN, Seymour AJ, Park HS, Bain PA, Maranda L, Ogembo JG. Prevalence of human papillomavirus genotypes among African women with normal cervical cytology and neoplasia: a systematic review and meta-analysis. PLoS ONE 2015;10:e0122488.

Lee WC, Lee SY, Koo YJ, Kim TJ, Hur SY, Hong SR, et al. Establishment of a Korea HPV cohort study. J Gynecol Oncol. 2013;24:59–65.

Park HK, Kang YM, Park JM, Choi YJ, Kim YN, Jeong DH, Kim KT. Prevalence and genotyping of HPV in different grades of cervical intraepithelial neoplasia and cervical cancer. Korean J Gynecol Oncol Colposc. 2003;14:12332.

Cho EJ, Do JH, Kim YS, Bae S, Ahn WS. Evaluation of a liquid bead array system for high-risk human papillomavirus detection and genotyping in comparison with hybrid capture II, DNA chip and sequencing methods. J Med Microbiol. 2011;60:162–71.

Lee D, Kim S, Park S, Jin H, Kim TU, Park KH, Lee H. Human papillomavirus prevalence in Gangwon province using reverse blot hybridization assay. Korean J Pathol. 2011;45:34853.

Kyeong HE, Ha SY, Chung DH, Kim NR, Park S, Cho HY. The usefulness of the HPV DNA microchip test for women with ASC-US. Korean J Pathol. 2009;43:2549.

Hwang HS, Park M, Lee SY, Kwon KH, Pang MG. Distribution and prevalence of human papillomavirus genotypes in routine pap smear of 2,470 Korean women determined by DNA chip. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev. 2004;13:2153–6.

Kwon JE, Kim YS, Kim SJ, Na YJ, Kim IH, Lee SY, et al. Establishment of general primers and oligo-DNA chip for the detection and typing of human papillomavirus. Korean J Gynecol Oncol Colposc. 2004;15:2319.

Kahng J, Lee HJ. Clinical efficacy of HPV DNA chip test in the era of HPV vaccination: 1,211 cases, a single institution study. Korean J Lab Med. 2008;28:70–8.

Kim MJ, Kim JJ, Kim S. Type-specific prevalence of high-risk human papillomavirus by cervical cytology and age: data from the health check-ups of 7,014 Korean women. Obstet Gynecol Sci. 2013;56:110–20.

Lee KO, Jeong SJ, Park MY, Seong HS, Shin ES, Choi KH, et al. Prevalence of human papillomavirus genotypes in routine Pap smear of 2,562 Korean women determined by PCR-DNA sequencing. J Bacteriol Virol. 2009;39:337–44.

Lee B, Suh DH, Kim K, Kim YB. Utility of human papillomavirus genotyping for triage of patients with atypical squamous cells of undetermined significance by cervical cytology. Anticancer Res. 2015;35:4197–202.

Park MS, Cho HW, Kim JG, Bae NY, Oh DS, Park HH. Genotype analysis of human papilloma virus infection in accordance with cytological diagnoses. Korean J Clin Lab Sci. 2015;47:39–45.

Nah EH, Cho S, Kim S, Cho HI. Human papillomavirus genotype distribution among 18,815 women in 13 Korean cities and relationship with cervical cytology findings. Ann Lab Med. 2017;37:426–33.

Oh JK, Alemany L, Suh JI, Rha SH, Muñoz N, Bosch FX, et al. Type-specific human papillomavirus distribution in invasive cervical cancer in Korea, 1958–2004. Asian Pac J Cancer Prev. 2010;11:993–1000.

Park TC, Kim CJ, Koh YM, Lee KH, Yoon JH, Kim JH, et al. Human papillomavirus genotyping by the DNA chip in the cervical neoplasia. DNA Cell Biol. 2004;23:119–25.

Seo HH, Kim YJ, Jeong MS, Hong SR, Lee IH, So KA, et al. Combined SYBR Green real-time polymerase chain reaction and microarray method for the simultaneous determination of human papillomavirus loads and genotypes. Obstet Gynecol Sci. 2016;59:489–97.

Shin HR, Lee DH, Herrero R, Smith JS, Vaccarella S, Hong SH, et al. Prevalence of human papillomavirus infection in women in Busan. South Korea Int J Cancer. 2003;103:413–21.

Chung S, Shin S, Yoon JH, Roh EY, Seoung SJ, Kim GP, Kim E. Prevalence and genotype of human papillomavirus infection and risk of cervical dysplasia among asymptomatic Korean women. Ann Clin Microbiol. 2013;16:87–91.

Hong SR, Kim IS, Kim DW, Kim MJ, Kim AR, Kim YO, et al. Prevalence and genotype distribution of cervical human papillomavirus DNA in Korean women: a multicenter study. Korean J Pathol. 2009;43:342–50.

Kim S, Lee D, Kim Y, Kim GH, Park SJ, Choi YI, et al. Clinical evaluation of human papillomavirus DNA genotyping assay to diagnose women cervical cancer. J Exp Biomed Sci. 2012;18:123–30.

Tong SY, Lee YS, Park JS, Namkoong SE. Human papillomavirus genotype as a prognostic factor in carcinoma of the uterine cervix. Int J Gynecol Cancer. 2007;17:1307–13.

Lee WS, Park JT, Lee GH, Seong SJ, Jung SE, Lee NW, Lee KW. The efficacy of HPV DNA chip test in the atypical squamous cell of undetermined significance. Korean J Gynecol Oncol. 2005;16:323–32.

An HJ, Cho NH, Lee SY, Kim IH, Lee C, Kim SJ, et al. Correlation of cervical carcinoma and precancerous lesions with human papillomavirus (HPV) genotypes detected with the HPV DNA chip microarray method. Cancer. 2003;97:1672–80.

Wu J, Ding C, Liu X, Zhou Y, Tian G, Lan L, et al. Worldwide burden of genital human papillomavirus infection in female sex workers: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Int J Epidemiol. 2021;50:527–37.

Li M, Du X, Lu M, Zhang W, Sun Z, Li L, et al. Prevalence characteristics of single and multiple HPV infections in women with cervical cancer and precancerous lesions in Beijing. China J Med Virol. 2019;91:473–81.

Jaisamrarn U, Castellsagué X, Garland SM, Naud P, Palmroth J, Del Rosario-Raymundo MR, et al. Natural history of progression of HPV infection to cervical lesion or clearance: analysis of the control arm of the large, randomised PATRICIA study. PLoS ONE 2013;8:e79260.

Ho GY, Burk RD, Klein S, Kadish AS, Chang CJ, Palan P, et al. Persistent genital human papillomavirus infection as a risk factor for persistent cervical dysplasia. J Natl Cancer Inst. 1995;87:1365–71.

Liaw KL, Hildesheim A, Burk RD, Gravitt P, Wacholder S, Manos MM, et al. A prospective study of human papillomavirus (HPV) type 16 DNA detection by polymerase chain reaction and its association with acquisition and persistence of other HPV types. J Infect Dis. 2001;183:8–15.

Kay P, Soeters R, Nevin J, Denny L, Dehaeck CM, Williamson AL. High prevalence of HPV 16 in South African women with cancer of the cervix and cervical intraepithelial neoplasia. J Med Virol. 2003;71:265–73.

Seong J, Ryou S, Yoo M, Lee J, Kim K, Jee Y, et al. Status of HPV vaccination among HPV-infected women aged 20–60 years with abnormal cervical cytology in South Korea: a multicenter, retrospective study. J Gynecol Oncol 2020;31:e4.

Acknowledgements

The authors thank the staff of the Korea HPV Cohort Study and the six hospitals involved in the study.

Funding

This study was funded by the Chronic Infectious Disease Cohort Study (4800-4859-304) from the Korea Disease Control and Prevention Agency (KDCA) and an Intramural Research Fund (2019-NI-068-01) from the Korea National Institute of Health (KNIH).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Consortia

Contributions

JS drafted the manuscript, contributed to the data collection for systematic review and data analyses. SR contributed to the manuscript revision, data collection, and interpretation. JGL and MY contributed to data collection and analyses. SH administrated the Korea HPV Cohort Study and data collection. BSC designed and conceived the study, supervised all aspects of its implementation, coordinated funding for the project, and critically reviewed the manuscript. All the authors reviewed and approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

We obtained approval from the IRB of the Korea Disease Control and Prevention Agency (KDCA) for this study (approved no. 2018–06-02-P-A). All participants in the Korea HPV Cohort Study provided written informed consent.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary Information

Additional file 1

. Characteristics of the studies included in the systematic review.

Additional file 2

. Basic characteristics of women at baseline in the Korea HPV Cohort Study (n = 1,664).

Additional file 3

. Risk of disease progression to HSIL by persistent HPV infections (single/multi-infection).

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/. The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver (http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/) applies to the data made available in this article, unless otherwise stated in a credit line to the data.

About this article

Cite this article

Seong, J., Ryou, S., Lee, J. et al. Enhanced disease progression due to persistent HPV-16/58 infections in Korean women: a systematic review and the Korea HPV cohort study. Virol J 18, 188 (2021). https://doi.org/10.1186/s12985-021-01657-2

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s12985-021-01657-2