Abstract

Background

Mosquito-borne flaviviruses are prime pathogens and have been a major hazard to humans and animals. They comprise several arthropod-borne viruses, including dengue virus, yellow fever virus, Japanese encephalitis virus, and West Nile virus. Culex flavivirus (CxFV) is a member of the insect-specific flavivirus (ISF) group belonging to the genus Flavivirus, which is widely distributed in a variety of mosquito populations.

Methods

Viral nucleic acid was extracted from adult mosquito pools and subjected to reverse transcriptase nested polymerase chain reaction (PCR) using target-specific primers for detecting CxFV nonstructural protein 5 (NS5). The PCR-positive samples were then sequenced, and a phylogenetic tree was constructed, including reference sequences obtained from GenBank.

Results

21 pools, belonging to Culex pipiens pallens (Cx. p. pallens) were found to be positive for the CxFV RNA sequence, with a minimum infection rate of 14.5/1000 mosquitoes. The phylogenetic analysis of the NS5 protein sequences indicated that the detected sequences were closely related to strains identified in China, with 95–98% sequence similarities.

Conclusion

Our findings highlight the presence of CxFV in Cx. p. pallens mosquito species in Jeju province, Republic of Korea. This is the first study reporting the prevalence of CxFV in Culex Pipiens (Cx. pipiens) host in the Jeju province, which can create possible interaction with other flaviviruses causing human and animal diseases. Although, mosquito-borne disease causing viruses were not identified properly, more detailed surveillance and investigation of both the host and viruses are essential to understand the prevalence, evolutionary relationship and genetic characteristic with other species.

Similar content being viewed by others

Background

Mosquito-borne flavivirus infection has been a major hazard to human health until the twenty-first century, particularly in tropical and subtropical regions [1]. The genus Flavivirus belongs to the family Flaviviridae, which comprises approximately 73 arthropod-borne viruses such as dengue virus (DENV), yellow fever virus (YFV), Japanese encephalitis virus (JEV), and West Nile virus (WNV), which infect rodents, pigs, humans, and other mammalian hosts. Flaviviruses are the most prevailing arthropod-borne viruses and among them many are identified as human pathogens. Flaviviruses shows similarity in genomic organizations but differ in transmissibility and their host ranges [2]. Most of them are dual-host flaviviruses that possess horizontal transmission between vertebrate hosts and arthropod vectors. However, not all flaviviruses are dual-host in nature; some are vertebrate-specific (No known vector virus) and others are insect-specific flavivirus (ISFs) that replicate only in insect cells and not in vertebrate cells [3].

Culex flavivirus (CxFV) is an ISF that was first identified in 2003–2004 in Culex species in Japan and Indonesia [4]. CxFV was later identified in field mosquito populations in many other countries which lead to the discovery of several distinct ISFs in the last few years [5, 6]. Though many flaviviruses are still endemic in tropical areas [7], the topographical alteration, rapid urbanization, and extensive deforestation have contributed to the increased prevalence of these pathogens in previously non-endemic areas [8, 9]. This, in turn, forms the basis for a wide variety of clinical indications, such as undifferentiated fever and encephalitis, which may potentially lead to death.

The objective of the study was to investigate the presence of flaviviruses in the mosquitoes of Jeju region using broad-spectrum primers targeting the NS5 gene. Further, we aimed to detect the presence of ISF CxFV in these mosquito species.

Here, we reported the abundance of vector mosquito Cx. pipiens, carrying the ISF CxFV in urban areas of Jeju province of the Republic of Korea (ROK) during 2018. This study could provide basis for further detailed investigation on the prevalence, evolutionary relationship and genetic characteristic with other species.

Materials and methods

Collection of mosquitoes

Adult mosquitoes were collected monthly from March to November 2018 using BL (black light trap) and BG (Biogents' Sentinel 2 Mosquito Trap) traps at several locations in the Jeju region: Hado-ri (33.5150° N, 126.8818° E on Jeju Island), Seohong-ro (33.2671° N, 126.5486° E on Jeju Island), Yeongcheon-dong (33.2688° N, 126.5870° E on Jeju Island), and Jungang-dong (33.2507° N, 126.5651° E). The region was divided into cattle sheds, habitats of migratory birds, and downtown areas (Fig. 1).

Following field trapping, all collected mosquitoes were examined visually and microscopically to identify female mosquitoes, and kept at 6ºC until being transferred to the laboratory [10, 11]. The mosquitoes were divided into several pools according to their species, date, and place of collection. The identification and confirmation of the female mosquitoes were done morphologically with the help of specialized taxonomic keys [12, 13]

A total of 1877 mosquitoes were grouped into 207 mosquito pools (1–40 mosquitoes in each pool) belonging to 13 distinct species of the genera Culex, Ochlerotatus, Anopheles, Mansonia, Armigeres, and Aedes. The mosquito samples were stored at − 80 °C before being processed for further molecular detection.

Nucleic acid extraction and polymerase chain reaction (PCR) amplification

A BioSpec Mini-BeadBeater 16 (Bio Spec Products Inc.; Bartlesville, OK, USA) was used to homogenize the sample pools with glass beads. Sterile phosphate-buffered saline (PBS, 800 µl) was added to each sterile micro beading tube (2 mL) containing a sample pool and homogenized. The homogenates were then centrifuged at 13,000 rpm for 1 min and 140 µL supernatant was used for viral RNA extraction using the QIAamp 96 Virus QIAcube HT kit (QiagenSciences; Germantown, MD, USA) in accordance with the manufacturer’s instructions.

Then, cDNA was synthesized using the extracted RNA as a template. The synthesized cDNA was then used in reverse transcription-based nested PCR (RT-nPCR) with primers detecting the NS5 partial gene specific to the flavivirus (212 bp) [14]. Two sets of primers were used: PanF-NS5-1373F and PanF-NS5-2481R for the initial amplification, and FL-F1, FL-R3, and FL-R4 to obtain a 212 bp product.

An AB thermal cycler (Applied Biosystems; Foster City, CA, USA) was used for PCR amplification. The reaction mixture comprised 20 μL solution including AccuPowerR PCR PreMix (Bioneer Corp.), 1 μL 10 pmol/μL primers (forward and reverse), 2 μL template cDNA (for the first PCR) or first PCR product (for the second PCR), and 16 μL sterile distilled water. A suitable positive control (DENV, Zika virus, YFV, and tick-borne encephalitis virus) and molecular grade water (as a negative control) were included in each run.

All primers used for the specific target gene and PCR cycling conditions along with the product sizes are given in Table 1.

A consensus region of the NS5 gene was targeted by two sets of flavivirus-specific primers [14] for the detection of all flaviviruses. Here, the amplification products were expected to be 212 bp long. The amplicons were separated by electrophoresis using a 1.5% agarose gel and visualized by ethidium bromide staining. Furthermore, all PCR-positive products were subjected to nucleotide sequencing.

Nucleotide sequencing, phylogenetic analysis, and calculation of the minimum infection rate (MIR)

To sequence the nucleotides of the amplified region for flaviviruses, PCR-positive samples were purified using a QIAquick Gel Extraction Kit (QIAGEN; Hilden, Germany). The amplicons from mosquito samples were sequenced by Cosmo Genetech (Daejeon, ROK). The Basic Local Alignment Search Tool (BLAST) was used to compare the obtained sequences to the GenBank deposited sequences. Default search parameters were used [15].

NS5 gene sequences were obtained from GenBank, and phylogenetic trees were constructed using Mega X [16] based on the alignments of positive gene sequences using the maximum likelihood (ML) method [17]. The tree is drawn to scale, with branch lengths measured in the number of substitutions per site. The percentage of replicate trees in which nodes were recovered under the bootstrap analysis (1,000 replicates) was calculated. Minimum infection rate (MIR) was calculated which was used as virus activity index in mosquito populations. The MIR was calculated using equation [18]:

Results

A total of 1877 mosquitoes belonging to 13 different species, including four species of Culex, two species of Anopheles and Aedes, three species of Ochlerotatus, and single species of Mansonia and Armigeres were captured using BG and BL traps at four trapping sites on Jeju Island, ROK between March and November 2018 (Table 2).

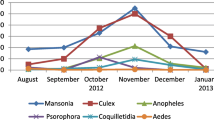

Most mosquitoes were captured in June, August, and October (Fig. 2). The most predominant species detected were Culex species (77.2%). All trapped mosquitoes were female.

The collected mosquitoes were grouped into 207 pools based on their species, date, and place of collection. Each of the mosquito pools was tested by PCR for the presence of flaviviruses and the only flavivirus that was detected was the ISF CxFV from the host Cx. p. pallens. A total of 21 pools were found positive for CxFV. The details are shown in Table 3. These mosquitoes were collected mainly from fields, nests of migrating birds, and ground water, mostly in the Jungang-dong area and several other locations in the Hado-ri and Seohong-ro areas of Jeju. The CxFVs from Cx. p. pallens were identified using species-specific RT-PCR targeting NS5 gene. The remaining pools with 12 other mosquito species were negative for flaviviruses using RT-PCR. The nucleotide sequences detected in all the RT-PCR positive samples were found to be 96–98% similar with sequences retrieved from GenBank (181–212 nucleotides). An NCBI BLAST analysis for each sequence showed that the top-ranking hit was that of CxFVs from Cx. p. pallens hosts (Table 4). One sample that tested positive for CxFV showed 95% similarity to Cx. p. pallens strain DG5, which was first reported in China in 2011 (GenBank accession no. JQ409191). A phylogenetic tree was also constructed based on NS5 (212 bp) gene sequences, which indicated that most of the CxFV isolates were clustering together forming a sister lineage which has common ancestral origin (Fig. 3). One of the isolate 4Mos P5 (MZ444122) was identified as a distant single divergent sequence (Fig. 3).

Phylogenetic tree was constructed based on the NS5 target gene (212 bp) of mosquito samples positive for Culex flavivirus (filled circle) and flavivirus sequences from GenBank.. See Table 4 for the GenBank accession numbers of Culex flavivirus sequences (Jeju, ROK).The tree was inferred by using the Maximum Likelihood method (ML) and General Time Reversible model (GTR). The tree is drawn to scale, with branch lengths measured in the number of substitutions per site. Evolutionary analyses were conducted in MEGA X. Scale bar indicates 0.01 (nucleotide substitution per site) sequence distance

Discussion

Recently, several flaviviruses have been sequenced, characterized, and identified in arthropods. The slow transition of the Korean climate from temperate to subtropical may also render the Korean Peninsula an ideal biological environment for the proliferation of mosquitoes as disease vectors in the near future [19]. In this study we aimed to investigate the presence of flaviviruses in the mosquitoes, and detected the presence of ISF CxFV in Culex species in the urban areas of Jeju province of the ROK.

CxFV from Cx. pipiens was the first ISF reported in Japan (2003–2004) [3] and China (2012) [20]. Since then, several other strains of CxFV have been documented [21, 22]. The Cx. pipiens vector plays the crucial rule in transmitting number of viruses which can cause not only bancroftian filariasis and Japanese encephalitis [23], but also other human and animal diseases, such as Rift Valley fever, Zika, St Louis encephalitis, and dog heartworm [24, 25].

Presently, vivax malaria and DENV infections are the most common mosquito-borne infectious diseases present in ROK, and almost 1171 clinical cases of dengue fever have been reported from 2015–2019 [19]. Additionally, 129 cases of JEV infection and 33 cases of Zika virus infection were also reported during 2015–2019 [20]. Furthermore, the Cx. pipiens species, a vector of WNV, was also found throughout ROK [26, 27]. Thus, monitoring these disease vectors is necessary to identify the possible interaction with other flaviviruses significant to public health [26, 28, 29].

Cx. pipiens is also the most common mosquito species in ROK [30]. The high feeding rates of mosquitoes on mammalian hosts, including humans [31], create an urgent need to study the role of Cx. pipiens in flavivirus transmission. Furthermore, continuous globalization and drastic climate change are also crucial factors for the spread of mosquito-borne diseases in the Jeju region, and therefore render these mosquitoes a threat for local inhabitants [32].

In this study, we collected the mosquito samples and the most predominant mosquito species identified was Cx. p. pallens, which accounted for 77.2% of the total population of 1,877 mosquitoes, followed by Aedes albopictus (8.7%), Chinese Anopheles sinensis (4.9%), and finally Culex tritaeniorhynchus (1.6%), a vector of JEV. Previously, Lee and Hwang [33] also reported similar prevalence for Cx. pipiens and Aedes albopictus; however, the prevalence of A. sinensis in this study was different from their results. Culex tritaeniorhynchus prevalence was also lower than the values reported by them (0.4%). The differences in topography, climate, and environment of the chosen areas in the two studies may explain the discrepancy in the reported results [32].

Total 207 pools were tested among which only 21 pools showed positive result for CxFV using RT-nPCR. The percentage of positive samples is low, only 10.15% (21/207 pools). The limited number of positive samples is closely related to those reported by Bryan et al. (2005) in Vietnam (26/1122 pools, 2.3%) and Ochieng et al. (2007–2012) in Kenya where only 0.3% pools were positive for CxFV [34, 35]. Additionally, Morais-Bronzoni et al. also reported the sensitivity of nested PCR assay for flaviviral detection of low viral load samples [36].

The positive pools were identified from the Cx. p. pallens host at the migratory bird’s nest, field and ground water area. No other ISF and pathogenic flaviviruses were detected in our study which is very similar to those reported by Bahk et al. [37]. The abundance of Cx. p. pallens was mostly observed in the Jungang-dong area of Jeju that shows the predominance of this species in the urban region [37].

The host of CxFV usually shows great diversity which could influence their phylogeny. CxFV has been detected from wide range of mosquitoes such as Cx. pipiens, Culex quinquefasciatus, and other mosquito species around the world [38, 39]. In this study a phylogenetic analysis was performed which showed two main clades with dissimilar branch length. The first clade was mainly associated with strains/isolates from Asia and USA. Cx. Pipiens species (in particular Cx. p. pallens) was the most common host identified from this clade. All of the sequences identified in our study showed more phylogenetical resemblance with this clade. The phylogenetic analysis revealed that all the newly isolated sequences were clustered together forming a single sister lineage, but the isolates were distinct from the Chinese isolates such as ZCB10 (MK422516), DG1064 (JQ308188). Among all the newly isolated sequences only 4Mos P5 (MZ444122) isolate showed the single divergent nature. Additionally, other CxFV host such as Anopheles sinensis (JQ308188) [38] and Culex quinquefasciatus (HQ634596, HQ634594, HQ634598, and FJ502995) were also reported in this group.

The second clade group of CxFV was mostly associated with strains/isolates from Asia, America, and Africa where Culex quinquefasciatus (JX897906, AB488433, AB639348, KY349933, EU879060, MH719098, and GQ165808) was reported as a main host [38, 39]. Additionally, Culex tritaeniorhynchus (JX897904) and Culex erraticus (KM081647) were also reported as a host. Nevertheless, it's crucial to note, that these genotypes are mainly based on the phylogenetic study of the viral polyprotein and envelope (E) gene, whereas our phylogenetic research was done with the NS5 gene.

The prevalence of Cx. p. pallens was relatively higher than that of other species. The MIR of CxFV in Cx. p. pallens was 14.5/1000 mosquitoes. A study by Kulasekera et al., (New York, 2000) also reported the MIR of WNV 8–14/1000 mosquitoes (Cx. pipiens and Cx. restuans) [40]. The pairwise nucleotide sequence identity results for the samples tested positive for CxFV were also clearly in accordance with the recommended flavivirus identification criteria (> 84%) based on the conserved region of the partial NS5 gene [41]. The detected sequences showed 95–98% sequence identity and clustered together within CxFV clade. These results confirm the presence of CxFV in Cx. pipiens species on Jeju Island. A significant limitation of this study is that only partial sequences (212 bp) of conserved NS5 region were used for phylogenetic analysis. However, this study reports significant findings that we believe can provide better understanding to perform further research in this area.

Conclusion

Previous surveys based on the Jeju area consistently showed no domestic cases of mosquito-borne flaviviruses [33, 42]. Thus, this study reports for the first time the presence of CxFV in Cx. p. pallens in the Jeju province of ROK. The abundance of this species in the Jeju area also indicates the possible interaction with other flaviviruses causing human and animal diseases like WNV, Rift Valley fever. Therefore, intensified monitoring and long-term surveillance studies of both the vectors and viruses are essential to elucidate interaction effect. Future studies should be performed to detect more CxFV in Jeju and other region of ROK to understand the diversity, evolutionary relationship and their genetic characteristic with other species.

Availability of data and materials

Data and materials are available upon request to the corresponding author.

Change history

20 August 2021

A Correction to this paper has been published: https://doi.org/10.1186/s12985-021-01639-4

Abbreviations

- BG:

-

Biogents' Sentinel 2 Mosquito Trap

- BL:

-

Black light trap

- BLAST:

-

Basic Local Alignment Search Tool

- CxFV:

-

Culex Flavivirus

- DENV:

-

Dengue virus

- ISFs:

-

Insect-specific flaviviruses

- JEV:

-

Japanese encephalitis virus

- MIR:

-

Minimum infection rate

- NCBI:

-

National Center for Biotechnology Information

- N-J:

-

Neighbor-joining

- NS5:

-

Nonstructural gene 5

- PBS:

-

Phosphate-buffered saline

- PCR:

-

Polymerase chain reaction

- ROK:

-

Republic of Korea

- RT-NPCR:

-

Reverse transcription-based nested PCR

- WNV:

-

West Nile virus

References

Susan L. Hills, Marc Fischer in, Principles and Practice of Pediatric Infectious Diseases (Fifth Edition), 2018.

Blitvich BJ, Firth AE. Insect-specific flaviviruses: a systematic review of their discovery, host range, mode of transmission, superinfection exclusion potential and genomic organization. Viruses. 2015;7(4):1927–59.

Cook S, et al. Molecular evolution of the insect-specific flaviviruses. J Gen Virol. 2012;93:223–34.

Hoshino K, Isawa H, Tsuda Y, Yano K, Sasaki T, Yuda M, Takasaki T, Kobayashi M, Sawabe K. Genetic characterization of a new insect flavivirus isolated from Culex pipiens mosquito in Japan. Virology. 2007;359:405–14.

Colmant AMG, Hobson-Peters J, Bielefeldt-Ohmann H, et al., A New Clade of Insect-Specific Flaviviruses from Australian Anopheles Mosquitoes Displays Species-Specific Host Restriction. mSphere 2017; 2(4), e00262-17

Gravina HD, Suzukawa AA, Zanluca C, et al. Identification of insect-specific flaviviruses in areas of Brazil and Paraguay experiencing endemic arbovirus transmission and the description of a novel flavivirus infecting Sabethes belisarioi. Virology. 2019;527:98–106.

Amaral DC, et al. Intracerebral infection with dengue-3 virus induces meningoencephalitis and behavioral changes that precede lethality in mice. J Neuroinflamm. 2011;8:23.

Shi, P-Y (editor) (2012). Molecular Virology and Control of Flaviviruses. Caister Academic Press. ISBN 978-1-904455-92-9.

McLean BJ, et al. A novel insect-specific flavivirus replicates only in Aedes-derived cells and persists at high prevalence in wild Aedes vigilax populations in Sydney, Australia. Virology. 2015;486:272–83.

Barraud PJ. The Fauna of British India Including Ceylon and Burma. Diptera. Volume V. Family Culicidae. Tribes Megarhinini and Culicini. Taylor and Francis (1934).

Reuben R, et al. Illustrated keys to species of Culex (Culex) associated with Japanese encephalitis in Southeast Asia (Diptera: Culicidae). Mosq Syst. 1994;26:75–96.

Ree HI. Taxonomic review and revised keys of the Korean mosquitoes (Diptera: Culicidae). Korean J Entomol. 2003;33(1):39–52.

Lee KW. A revision of the illustrated taxonomic keys to genera and species of mosquito larvae of Korea. Department of the Army, 5th Medical Detachment, 18th Medical Command; 1999

Yang CF, et al. Screening of mosquitoes using SYBR Green I-based real-time RT-PCR with group-specific primers for detection of flaviviruses and alphaviruses in Taiwan. J Virol Methods. 2010;168:147–51.

Altschul SF, et al. Gapped BLAST and PSI-BLAST: a new generation of protein database search programs. Nucleic Acids Res. 1997;25:3389–402.

Kumar S, Stecher G, Li M, Knyaz C, Tamura K. MEGA X: molecular evolutionary genetics analysis across computing platforms. Mol Biol Evol. 2018;35:1547–9.

Nei M, Kumar S. Molecular evolution and phylogenetics. New York: Oxford University Press; 2000.

Bernard KA, et al. West Nile virus infection in birds and mosquitoes, New York State, 2000. Emerg Infect Dis. 2001;7(4):679–85.

Yeom JS. Current status and outlook of mosquito-borne diseases in Korea. J Korean Med Assoc. 2017;60(6):468–74.

Wang H, et al. Isolation and identification of a distinct strain of Culex flavivirus from mosquitoes collected in mainland China. Virol J. 2012;9:73.

Liang W, et al. Distribution and phylogenetic analysis of Culex flavivirus in mosquitoes in China. Arch Virol. 2015;160:2259–68.

An S, et al. Isolation of the Culex flavivirus from mosquitoes in Liaoning Province. China Chin J Virol. 2012;28:511–6.

Wu-chun C, Jin-fan X, Zheng-xuan R. Epidemiological surveillance of filariasis after its control in Shandong Province, China. Southeast Asian J Trop Med Public Health. 1994;25:714–8.

Kim N-J, Chang K-S, Lee W-J, Ahn Y-J. Monitoring of insecticide resistance in field-collected populations of Culex pipiens pallens (Diptera: Culicidae). J Asia Pac Entomol. 2007;10:257–61.

Cui J, Li S, Zhao P, Zou F. Flight capacity of adult Culex pipiens pallens (Diptera: Culicidae) in relation to gender and day-age. J Med Entomol. 2013;50:1055–8.

Korea Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (KCDC) (2016) Disease Web Statistic System [in Korean]. 2016 [cited 2017 Jul 20].

Bae W, Kim JH, Kim J, Lee J, Hwang ES. Changes of epidemiological characteristics of Japanese encephalitis viral infection and birds as a potential viral transmitter in Korea. J Korean Med Sci. 2018;33:e70.

Chang KS, et al. Monitoring and control of Aedes albopictus, a vector of Zika virus, near residences of imported Zika virus patients during 2016 in South Korea. Am J Trop Med Hyg. 2018;98:166–72.

Park S, Cho E. National infectious diseases surveillance data of South Korea. Epidemiol Health. 2014;36:e2014030.

Tanaka K, Mizusawa K, Saugstad ES. A revision of the adult and larval mosquitoes of Japan (including the Ryukyu Archipelago and the Ogasawara Islands) and Korea (Diptera: Culicidae). Contrib Am Ent Inst. 1979; 16: vii + 1–987.

Hamer GL, et al. Culex pipiens (Diptera: Culicidae): a bridge vector of West Nile virus to humans. J Med Entomol. 2008;45:125–8.

Lee SH, et al. The effects of climate change and globalization on mosquito vectors: evidence from Jeju Island, South Korea on the potential for Asian tiger mosquito (Aedes albopictus) influxes and survival from Vietnam rather than Japan. PLoS ONE. 2013;8(7):e68512.

Lee CW, Hwang KK. Mosquito distribution and detection of flavivirus using real time RT-PCR in Jeju island 2017. Korean J Appl Entomol. 2018;57:177–83.

Bryant JE, Crabtree MB, Nam VS, Yen NT, Duc HM, Miller BR. Isolation of arboviruses from mosquitoes collected in northern Vietnam. Am J Trop Med Hyg. 2005;73(2):470–3.

Ochieng C, Lutomiah J, Makio A, Koka H, Chepkorir E, Yalwala S, et al. Mosquito-borne arbovirus surveillance at selected sites in diverse ecological zones of Kenya; 2007–2012. Virol J. 2013;10:140.

de Morais Bronzoni RV, Baleotti FG, Ribeiro Nogueira RM, Nunes M, Moraes Figueiredo LT. Duplex reverse transcription-PCR followed by nested PCR assays for detection and identification of Brazilian alphaviruses and flaviviruses. J Clin Microbiol. 2005;43(2):696–702.

Young YB, Seo HP, Myung-Deok K-J. Monitoring Culicine Mosquitoes (Diptera: Culicidae) as a Vector of Flavivirus in Incheon Metropolitan City and Hwaseong-Si, Gyeonggi-Do, Korea, during 2019. Korean J Parasitol. 2020;58(5):551–8.

Liang W, He X, Liu G, Zhang S, Fu S, Wang M, et al. Distribution and phylogenetic analysis of Culex flavivirus in mosquitoes in China. Arch Virol. 2015;160(9):2259–68.

Bittar C, Machado DC, Vedovello D, Ullmann LS, Rahal P, Araujo Junior JP, et al. Genome sequencing and genetic characterization of Culex Flavirirus (CxFV) provides new information about its genotypes. Virol J. 2016;13(1):158.

Kulasekera VL, Kramer L, Nasci RS, et al. West Nile virus infection in mosquitoes, birds, horses, and humans, Staten Island, New York, 2000. Emerg Infect Dis. 2001;7(4):722–5.

Kuno G, et al. Phylogeny of the genus Flavivirus. J Virol. 1998;72(1):73–83.

Seo MY, Chung KA. Density and Distribution of the Mosquito Population Inhabiting Jeju Region, 2018. Korean J Clin Lab Sci. 2019;51(3):336–43.

Acknowledgements

None.

Funding

This research was supported by a grant from the Korea Health Technology R&D Project through the Korea Health Industry Development Institute (KHIDI), funded by the Ministry of Health & Welfare, Republic of Korea (grant number: HI20C0369).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

SC performed the experiment, collected data, wrote the manuscript, and revised the draft during submission. CMK and NRY revised the draft and were responsible for the experiment and data collection. DMK designed and coordinated the study and drafted and reviewed the manuscript during submission. SHJ and CKA revised the draft and analyzed the data. All authors have read and approved the final version of the manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

Not applicable.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors have no conflicts of interest to declare.

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/. The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver (http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/) applies to the data made available in this article, unless otherwise stated in a credit line to the data.

About this article

Cite this article

Chatterjee, S., Kim, CM., Yun, N. et al. Molecular detection and identification of Culex flavivirus in mosquito species from Jeju, Republic of Korea. Virol J 18, 150 (2021). https://doi.org/10.1186/s12985-021-01618-9

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s12985-021-01618-9