Abstract

Background

Approximately two thirds of stroke survivors maintain upper limb (UL) impairments and few among them attain complete UL recovery 6 months after stroke. Technological progress and gamification of interventions aim for better outcomes and constitute opportunities in self- and tele-rehabilitation.

Objectives

Our objective was to assess the efficacy of serious games, implemented on diverse technological systems, targeting UL recovery after stroke. In addition, we investigated whether adherence to neurorehabilitation principles influenced efficacy of games specifically designed for rehabilitation, regardless of the device used.

Method

This systematic review was conducted according to PRISMA guidelines (PROSPERO registration number: 156589). Two independent reviewers searched PubMed, EMBASE, SCOPUS and Cochrane Central Register of Controlled Trials for eligible randomized controlled trials (PEDro score ≥ 5). Meta-analysis, using a random effects model, was performed to compare effects of interventions using serious games, to conventional treatment, for UL rehabilitation in adult stroke patients. In addition, we conducted subgroup analysis, according to adherence of included studies to a consolidated set of 11 neurorehabilitation principles.

Results

Meta-analysis of 42 trials, including 1760 participants, showed better improvements in favor of interventions using serious games when compared to conventional therapies, regarding UL function (SMD = 0.47; 95% CI = 0.24 to 0.70; P < 0.0001), activity (SMD = 0.25; 95% CI = 0.05 to 0.46; P = 0.02) and participation (SMD = 0.66; 95% CI = 0.29 to 1.03; P = 0.0005). Additionally, long term effect retention was observed for UL function (SMD = 0.42; 95% CI = 0.05 to 0.79; P = 0.03). Interventions using serious games that complied with at least 8 neurorehabilitation principles showed better overall effects. Although heterogeneity levels remained moderate, results were little affected by changes in methods or outliers indicating robustness.

Conclusion

This meta-analysis showed that rehabilitation through serious games, targeting UL recovery after stroke, leads to better improvements, compared to conventional treatment, in three ICF-WHO components. Irrespective of the technological device used, higher adherence to a consolidated set of neurorehabilitation principles enhances efficacy of serious games. Future development of stroke-specific rehabilitation interventions should further take into consideration the consolidated set of neurorehabilitation principles.

Similar content being viewed by others

Background

Each year more than 1 million Europeans suffer from stroke and approximately two-thirds of survivors maintain upper limb (UL) paresis [1]. This number is expected to rise by 35% in upcoming years [2] leading to additional rehabilitation needs. To this date, few people attain complete UL recovery 6 months after stroke [3]. New interventions targeting the UL aim for better outcomes in activities of daily living (ADL), functional independence and quality of life. Alongside conventional therapies, recent developments offer possibilities in self- and tele-rehabilitation [4] which could help manage, cost-efficiently [5], increasing rehabilitation demands.

Technological improvements in robot assisted therapy (RAT) and virtual reality (VR) systems (VRS) enhance patient care and facilitate therapist assistance during UL rehabilitation [6, 7]. First, RAT promotes the use of the affected limb, intensifies rehabilitation through task repetition and offers task-specific practice [7]. Effectiveness of RAT is established for UL rehabilitation after stroke [8, 9]. Secondly, VRS provide augmented feedback, preserve motivation and are becoming cost-efficient [5]. Recent meta-analyses suggest a superior effect of VR-based interventions compared to conventional treatment on UL function and activity after stroke, especially if developed for this specific purpose [10–12]. Authors attributed these findings to the fact that VRS specifically developed for rehabilitation, as opposed to commercial video-games (CVG), fulfil numerous neurorehabilitation principles.

Typically, a common denominator of VRS and RAT is playful interventions by means of serious games [13, 14]. A serious game is defined as a game that has education or rehabilitation as primary goal. These games combine entertainment, attentional engagement and problem solving to challenge function and performance [15, 16]. Moreover, they comply with several motor relearning principles that constitute the basis of effective interventions in neurorehabilitation [11, 16]. For example, some devices adapt game difficulty to stimulate recovery and maintain motivation [15]. Others incorporate functional tasks mimicking ADL in virtual environments and provide performance feedback during and/or after task completion [17]. Characteristics of serious games differ depending on targeted rehabilitation purposes and technical specificities of the system they are implemented on.

Previous work on the efficacy of VR-based interventions indicated that serious games may enhance UL recovery after stroke [11, 12, 18]. However, why such interventions, specifically developed for rehabilitation purposes and implemented on various types of devices (such as robots, smartphones, tablets, motion capture systems, etc.), may constitute effective therapies for UL rehabilitation after stroke needs to be further investigated. Recent theoretical research proposed consolidation of commonly acknowledged neurorehabilitation principles [16]. Usually, serious games comply with several of these principles which creates an opportunity to evaluate clinical applicability of the consolidated set of principles. To this day, it remains unclear whether higher adherence to this consolidated set of neurorehabilitation principles enhances efficacy of interventions. In addition, it is not well known whether adherence to specific principles influences efficacy. Finally, rehabilitation effects on participation outcomes remain relatively unexplored. In this context, efficacy of interventions should be addressed in terms of all components of the World Health Organization’s International Classification of Function, Disability, and Health (ICF-WHO) model [19].

The main objective of this systematic review and meta-analysis was to address the following question in PICOS form: in adults after stroke (P), do serious games, implemented on various technological systems (I), show better efficacy than conventional treatment (C), to rehabilitate UL function and activity, and patient’s participation (O)? A secondary objective was to assess whether higher adherence to a consolidated set of neurorehabilitation principles enhances efficacy of games specifically designed for rehabilitation, irrespective of the technological device used.

Methods

Design

This systematic review followed the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analysis (PRISMA) guidelines [20]. The protocol was registered in International Prospective Register of Systematic Reviews (PROSPERO 2020, registration number: 156589).

Identification and study selection

A search strategy looking for relevant literature was developed for PubMed and adapted for the other databases, namely Scopus, Embase and Cochrane Library (Additional file 1). Authors received help from a professional librarian to set up the search strategy. Two investigators (GE and ID) independently retrieved studies. All references were stored in reference management software EndNote X9. After removal of duplicates, remaining references were first screened based on titles and abstracts.

Study eligibility was assessed according to the following criteria: (a) design of randomized controlled trials (RCT) (b) participants were adults undergoing stroke rehabilitation (c) the intervention consisted of games developed for neurorehabilitation purposes and implemented in the following technological devices: robotic systems, VRS, tablets, smartphones and motion capture systems (d) relevant outcomes were employed to assess UL function, UL activity and participation (e) studies were published in French or English before May 5th, 2020. All studies using additional therapeutic modalities such as brain stimulation, electrical stimulation or invasive treatments were excluded.

Systematic reviews assessing effectiveness of VR-based rehabilitation and RAT in stroke recovery were also hand-searched looking for relevant references. Finally, a selection based on full-text was conducted by the same two reviewers. Disagreements were resolved through discussion.

Quality and risk of bias assessment

The PEDro checklist was used for methodological quality assessment of trials [21]. In addition, the Cochrane Collaboration’s Risk of Bias (RoB) tool was employed to conduct a critical appraisal of each trial’s internal validity [22].

Data extraction

The following data concerning patients, interventions, control groups and outcomes were extracted from each study: number of patients enrolled in each group, mean time since stroke, corresponding stroke stage classification (subacute: 7 days to 6 months after stroke, chronic: more than 6 months after stroke) [23], dosage and duration of the intervention, technological device used, type and duration of treatment for the control group, presence of a follow-up assessment and outcomes assessed in each timepoint evaluation.

Studies were also assessed in terms of the number of neurorehabilitation principles their intervention fulfilled as described in the review of Maier et al. [11]. These authors described a total of 11 principles presented in Table 1. The two reviewers, independently, investigated whether interventions of included studies fulfilled each one of the neurorehabilitation principles. For each clearly identified principle, one point was attributed to the study. In case available information was vague, missing or did not match the neurorehabilitation principle descriptive’ (as mentioned in Table 1), no point was accorded. Then, we calculated a total score out of 11 for each included study.

Outcome measurements

Outcome measures were selected in accordance to the ICF-WHO model [19]. In each category, assessment scales were chosen based on recent literature recommendations [24, 25]. The Fugl-Meyer Assessment (FMA) [26] was used for the body function domain. The Action Research Arm Test (ARAT) [27], the Box and Block Test (BBT) [28] and the Wolf Motor Function Test (WMFT) [29] were used for the activity domain. The social participation subscale of the Stroke Impact Scale (SIS) [30] was used for the participation domain.

When available, mean improvements in terms of change-from-baseline and their standard deviation (SD) were extracted for each time point. If not available, authors were contacted via email. In case of non-response, the mean improvement was calculated through subtraction between post-intervention mean score and pre-intervention mean score. Then, the SD was estimated by using a formula according to the Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions [31]. The value of the correlation coefficient was imputed by using data from other studies [17, 32, 33] included in the meta-analysis. Lastly, when only median and quartiles were available, the mean and SD were approximated using the method proposed by Wan et al. [34]. For studies using follow-up evaluations at least one month after the intervention, mean improvements in terms of change-from-baseline were calculated in order to assess long-term effect retention.

Data and statistical analysis

Articles scoring below 5/10 on the PEDro scale were excluded due to overall poor methodological quality [35]. In addition, only trials that described conventional therapy used in the comparison group as including occupational, physical or self-therapy were considered for statistical analysis. Statistical analyses were performed using the RevMan 5.3 software [36]. Since different rating scales were used for studied outcomes and results were reported in various ways, standardized mean difference (SMD) and 95% confidence interval (CI) were calculated. This method allowed standardization of results across studies. A random effects meta-analysis model was used for all analyses and statistical significance level was set at P < 0.05 [37]. Heterogeneity across trials was estimated using the I2 test. Heterogeneity was not considered to be significative for a I2 < 30% [30].

Subgroup analysis was conducted for RCT whose intervention met at least 8/11 neurorehabilitation principles compared to RCT whose intervention fulfilled less. Another subgroup analysis was performed according to stroke stage, comparing effects of interventions using serious games on subacute and chronic stroke patients. Subgroup analysis were only considered when at least two trials in each subgroup reported a given domain. Furthermore, long-term effect retention for trials that measured outcomes at follow-up was evaluated.

Publication bias was evaluated visually through funnel plot graphic representation. Sensitivity analyses was conducted to verify results robustness in case of funnel plot asymmetry, heterogeneity or presence of outliers. Additional sensitivity analyses were conducted using two different values for correlation coefficient [30]. GRADEpro program was used to assess the strength of the body evidence [38].

Finally, a Fischer’s exact test was used to compare differences in proportions among studies, depending on their results, regarding adherence to each neurorehabilitation principle.

Results

Study selection

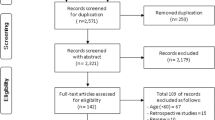

A total of 8141 trials were identified through search across all databases and 165 additional records through other sources. After removal of duplicates, 5131 articles were screened based on titles and abstracts. Among these, 5049 were excluded and 82 full-text articles were assessed for eligibility. 51 RCT were included in the qualitative synthesis. Finally, after quality assessment was performed, 42 RCT were considered for quantitative synthesis. Further details are illustrated in the study PRISMA flow chart (Fig. 1).

Study characteristics

A total of 2083 participants with a mean age ranging from 49.3 to 76.0 years were included in the qualitative synthesis. For each included study, we identified the mean age of the participants, the stroke stage classification and the type of device used for intervention (Table 2). Approximately one third (31%) of studies included stroke patients at subacute stage and two-thirds (69%) at chronic stage. Across trials, serious games were implemented on different types of devices: 26 (51%) used a motion capture system among which many low-cost systems (such as Microsoft Kinect for example), 10 (19%) used an end-effector type robot, 5 (9%) used motion capture gloves, 3 (7%) a robotic exoskeleton, 3 (6%) an immersive-VR system, 2 (4%) a smartphone or tablet, 1 (2%) a surface EMG-controlled sensor and 1 (2%) an arm support system.

For each trial, total treatment duration in terms of minutes per session, number of sessions per week and total number of weeks was identified. In addition, whether intervention and control groups were time-matched regarding these characteristics was verified (Table 3). Total number of weeks of treatment varied from 2 to 12 weeks with a mean of 5 weeks among trials. Daily duration of therapy varied widely among studies ranging from 30 to 225 min. In most trials (85%), total treatment duration was matched between the intervention and control groups (Table 3).

The number of neurorehabilitation principles fulfilled by serious games were identified through content analysis. This number varied from 4 to 11 (Table 3). For a total of 11 neurorehabilitation principles, 32 (63%) interventions met 8 or more, 17 (33%) met between 5 and 7 and 2 (4%) interventions met less than 5. Table 1 illustrates the percentage of studies included in meta-analysis that complied with each neurorehabilitation principle. In addition, Table 1 displays differences in adherence to each neurorehabilitation principle between studies with overall positive or negative results (based on each study SMD in quantitative synthesis results). Statistically significant differences were observed regarding the principle of explicit feedback. Indeed, the group of studies with overall positive results adheres more to this principle than the other group.

Regarding main outcomes, 44 trials (87%) assessed UL motor function, 30 (59%) assessed UL activity and 9 (17%) assessed participation (Table 3). Most trials (60%) reported significantly superior results in at least one ICF-WHO component in favour of interventions using serious games compared to conventional treatment.

Methodological quality and risk of bias assessment

PEDro scores of 51 included studies ranged from 5 to 8 with a mean (SD) of 6.33 (1.15) indicating an overall moderate to high methodological quality (Table 2). Detailed PEDro scale scoring for each trial is illustrated in Additional file 1: Table S1. In addition, the detailed analysis using the Cochrane Collaboration RoB tool is presented in Additional file 1: Fig. S1.

Effect of rehabilitation through serious games on UL motor function

In total, rehabilitation using serious games led to significantly better improvements, of moderate effect size, in UL motor function compared to conventional treatment (SMD = 0.47; 95% CI = 0.24 to 0.70; P < 0.0001) (Fig. 2). Subgroup analysis highlighted differences between results of trials using serious games fulfilling 8 or more neurorehabilitation principles and those that did not (P = 0.003). Indeed, only interventions that met 8 or more principles showed significant impact of moderate effect size on upper limb motor function (SMD = 0.62; 95% CI = 0.33 to 0.92; P = 0.0001). Although total results indicated considerable heterogeneity between studies (I2 = 76%), analysis using the GRADE approach led to a moderate certainty of evidence (Additional file 1: Fig. S2 illustrates detailed summary of findings).

Additional subgroup analysis was conducted based on the stroke stage of included participants across studies (Fig. 3). Results suggest that interventions using serious games were effective in improving UL motor function in both subacute (SMD = 0.35; 95% CI = 0.10 to 0.59; P = 0.006) and chronic stage after stroke (SMD = 0.57; 95% CI = 0.19 to 0.95; P = 0.003). Differences among subgroups did not reach statistical significance (P = 0.33).

Finally, in order to address heterogeneity, sensitivity analyses were performed in two ways. A first analysis was conducted by excluding outliers identified through funnel plot graphic representation (Additional file 1: Fig. S3). Then, a second analysis was carried out by using a different correlation coefficient value. In both cases, results indicate no significant differences in total estimates when compared to initial findings (Additional file 1: Figs. S4 and S5).

Effect of rehabilitation through serious games on UL activity

In total, rehabilitation using serious games led to significantly better improvements, of low effect size, in upper limb activity compared to conventional treatment (SMD = 0.25; 95% CI = 0.05 to 0.46; P = 0.02) (Fig. 4). In a similar way to results regarding UL function, subgroup analysis showed significantly better improvements, of moderate effect size, only for interventions that fulfilled 8 or more neurorehabilitation principles (SMD = 0.42; 95% CI = 0.12 to 0.72; P = 0.006). Differences among subgroups were statistically significant (P = 0.01). Total results indicated moderate heterogeneity between studies (I2 = 56%). Additional subgroup analysis based on stroke stage did not reach statistical significance for neither subacute or chronic stage after stroke (Additional file 1: Fig. S6).

Effect of rehabilitation through serious games on participation

In total, rehabilitation using serious games led to significantly better improvements, of large effect size, in participation compared to conventional treatment (SMD = 0.66; 95% CI = 0.29 to 1.03; P = 0.0005) (Fig. 5). No significant heterogeneity was present (I2 = 0%). All trials included in this analysis used a serious game that complied with 8 or more neurorehabilitation principles.

Analysis of follow-up data

Separate analyses were conducted regarding follow-up data for each ICF-WHO component. Only half of the studies included in the quantitative synthesis (50%) performed follow-up evaluations. Among them, length of follow-up period ranged from 1 to 6 months with a mean (SD) of 2.3 months (1.86). An overall tendency towards improvement for interventions using serious games regarding all ICF-WHO components was observed (Additional file 1: Figs. S7, S8 and S9). Total estimates concerning UL function indicate effect retention to follow-up in favour of the experimental group of moderate effect size (SMD = 0.42; 95% CI = 0.05 to 0.79; P = 0.03). Results did not reach statistical significance regarding UL activity and participation.

Discussion

Main results

This systematic review and meta-analysis showed results in favour of rehabilitation using, purpose-built, serious games on UL motor function, UL activity and participation after stroke compared to conventional treatment. Moreover, long term effect retention was significantly maintained regarding UL function. Irrespective of the technological device used, serious games that complied with more than 8 out of 11 neurorehabilitation principles showed better overall effects.

Previous studies on effectiveness of VRS/CVG for UL rehabilitation after stroke

Previous work on the use of VRS and CVG for UL rehabilitation after stroke demonstrated similar results [11, 17]. Yet, to date, usage and efficacy of game-based interventions for UL rehabilitation after stroke remain controversial [38–40]. Initially, a meta-analysis by Saposnik et al., combining observational studies and RCT, suggested improvements in UL strength and motor function after stroke [41]. However, this review focused on various VRS, including CVG designed by the entertainment industry, not specifically developed for rehabilitation. In addition, no statistically significant differences were observed concerning UL activity outcomes and no analysis was conducted regarding ICF-WHO participation component due to limited available data.

Two other groups conducted systematic reviews on a similar topic [42, 43]. However, both reviews included studies concerning not only UL rehabilitation but also gait and balance, making it difficult to draw conclusions regarding the UL. Palma et al., solely relying on qualitative synthesis, supported positive findings on function [42]. Results were inconclusive regarding activity and participation components and further interpretation was limited due to lack of quantitative synthesis. Then, a meta-analysis by Lohse et al. showed positive effects in favour of VR-based interventions regarding three ICF-WHO components [43]. However, analysis was restricted to therapies that did not include robotic assistance. Furthermore, analyses through meta-regressions did not point out significant differences in outcomes between commercially available and custom-built systems.

Two updated Cochrane reviews covered broader aspects of VR and robotics in UL rehabilitation after stroke [8, 10]. In the review by Mehrholz et al., high quality evidence supports better improvements in ADL, arm function and arm strength in favour of RAT [8]. Nonetheless, effects of robotic training performed in form of a serious game were not studied. Then, a review by Laver et al. on VR-based interventions, demonstrated equivalent improvements in UL function and activity when comparing time-matched interventions [10]. Notably, UL function and activity outcomes were pooled in one common analysis instead of distinguishing effects in terms of the two ICF-WHO components. Further analyses in subgroups suggested better results when specific systems designed for rehabilitation were employed compared to off-the-shelf CVG, although differences did not reach statistical significance.

Finally, two recent reviews showed improvements on both UL function and activity in groups receiving VR/gaming-based training after stroke [11, 18]. However, both reviews studied broader aspects of VR-based interventions and their scope was not delimited to specific use of serious games. Karamians et al. suggested that interventions with gaming components further promote recovery compared to those providing visual feedback only [18]. Then, Maier et al. distinguished VRS specifically built for rehabilitation purposes from others destined to generic use [11]. Results illustrated that, when compared to conventional therapy, interventions specifically designed based on elements enhancing neural plasticity led to significantly better results [11]. Additionally, it was suggested that custom-made interventions, in comparison to non-specific interventions, comply better with a series of neurorehabilitation principles.

Adherence to neurorehabilitation principles of interventions using serious games for UL rehabilitation after stroke

To this date, UL stroke recovery through games developed specifically for rehabilitation and implemented on diverse systems, has not been explicitly reviewed. In addition, most recent reviews delimit their scope in technological terms by considering interventions based on the devices being used [11, 12, 18]. Some authors characterise comparison between studies using different devices as difficult [44]. However, a holistic overview of serious games, regardless of the technology used, is important in order to better understand their added value in UL rehabilitation after stroke. Comparison between studies using systems with different technical specificities, mainly in hardware, is challenging. Nonetheless, interventions through serious games implemented on different devices may share similarities. Indeed, all studies included in our review perform non-invasive treatments. Then, gamification and adaptability of interventions, to the patients’ impairments and performance, aim to maintain motivation throughout therapy sessions [45]. Additionally, all these systems have the potential to give access to kinematic data allowing objective assessment, evaluating real-time performance and tracking UL recovery [46–48]. Finally, all interventions stimulate recovery through adherence to common neurorehabilitation principles. In fact, comparison across different types of technologies and treatment modalities leads to identification of common ‘active ingredients’ in terms of effective rehabilitation [11]. In accordance with recent literature, this review contributes to identifying a rationale regarding efficacy of interventions in UL rehabilitation after stroke. Our results point out that even in a group of interventions specifically developed for rehabilitation purposes, differences in outcomes may be explained depending on higher adherence to neurorehabilitation principles. Furthermore, even though most interventions seem to fulfil certain principles (task-specific practice, variable practice, massed practice), it seems that clusters of principles met among serious games may lead to differences in efficacy. For instance, our findings suggest that providing feedback during therapy appears to be an important characteristic that interventions using serious games should satisfy. Further, to what degree each individual principle contributes in efficacy is difficult to study. However, it appears that the more an intervention adheres to principles, the better the expected outcomes can be regarding motor recovery.

To the best of our knowledge, this systematic review is the first to address, in a non-fragmented way, efficacy of specifically designed gaming interventions in UL rehabilitation after stroke. Our results confirm current trends favouring custom-made rehabilitation systems and gamification of interventions. Positive findings concerning function and activity have already been reported in previous reviews [11, 18]. It is worth noting that this review shows encouraging results in participation outcomes indicating, therefore, improvements in three ICF-WHO components.

Strengths and limitations

In a rapidly emerging field, 40% of studies included in our review were published within the last 3 years. Quantitative synthesis was performed by only using RCT of moderate to high methodological quality. However, this was not feasible for two studies due to unavailable data. Additionally, even though our work was conducted according to PRISMA guidelines for systematic reviews, no methods were used to detect unpublished trials. Also, publication bias was only assessed through funnel plot graphic representation which nonetheless did not indicate asymmetry. Heterogeneity across studies was moderate to high regarding UL function and activity outcomes. This may be partially due to variation of elements such as patient characteristics, duration of interventions and evaluation timepoints. Heterogeneity was addressed by using a random effects model for meta-analyses and by conducting additional analyses. Even though heterogeneity levels remained moderate, our results were little affected by changes in methods or outliers, indicating robustness.

Perspectives

Our work offers some suggestions regarding clinical practice and future research. Interventions using serious games may be encouraged and integrated in upper limb rehabilitation programs during subacute and chronic stage after stroke. Specifications regarding dosage, duration and selection of patients that could benefit most from these treatments need further investigation. In addition, serious games should be explored in terms of ways to provide self- or tele-rehabilitation.

From a research point of view, new developments in gaming interventions can take into consideration adherence to neurorehabilitation principles. In accordance with our findings, future developments of interventions in UL stroke rehabilitation ought to comply with as many neurorehabilitation principles as possible. Future work should study how variations in clusters of these principles may influence differently specific aspects of motor or cognitive rehabilitation. Also, richness of kinematic data, accessible through technological devices on which games are implemented, open new perspectives in assessment and follow-up of stroke patients. In our review, only 11% of studies used kinematic data, complementary to clinical rating scales, for UL function evaluation. Finally, few studies (11%) included in our review reported cognitive outcomes. Since motor performance and functional recovery can be influenced by cognitive determinants [49, 50], combined assessment of all these aspects should be further considered in future work.

Conclusion

In conclusion, this systematic review and meta-analysis showed that post-stroke UL rehabilitation through serious games, implemented on various types of technological devices, showed better improvements, compared to conventional treatment, on three ICF-WHO components. Long term effect retention was maintained for UL function. Irrespective of the technological system used, serious games that complied with more than 8 out of 11 neurorehabilitation principles led to better overall effects. Our findings emphasize the importance of adherence to neurorehabilitation principles in order to improve efficacy of interventions in UL rehabilitation after stroke.

Availability of data and materials

All data generated or analysed during this study are included in this published article and its supplementary information files.

Abbreviations

- UL:

-

Upper limb

- ADL:

-

Activities of daily living

- VR:

-

Virtual reality

- VRS:

-

Virtual reality systems

- RAT:

-

Robot-assisted therapy

- CVG:

-

Commercial video-games

- ICF-WHO:

-

World Health Organization’s International Classification of Function, Disability, and Health

- RCT:

-

Randomized controlled trials

- FMA:

-

Fugl-Meyer assessment

- ARAT:

-

Action Research Arm Test

- BBT:

-

Box and block test

- SIS:

-

Stroke impact scale

- SMD:

-

Standardized mean difference

- CI:

-

Confidence interval

References

Béjot Y, Bailly H, Durier J, Giroud M. Epidemiology of stroke in Europe and trends for the 21st century. Presse Med. 2016;45(12 Pt 2):e391–8. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.lpm.2016.10.003.

Norrving B, Barrick J, Davalos A, Dichgans M, Cordonnier C, Guekht A, Caso V. Action plan for stroke in Europe 2018–2030. Eur Stroke J. 2018;3(4):309–36. https://doi.org/10.1177/2396987318808719.

Kwakkel G, Kollen BJ, van der Grond J, Prevo AJH. Probability of regaining dexterity in the flaccid upper limb: impact of severity of paresis and time since onset in acute stroke. Stroke. 2003;34:2181–6. https://doi.org/10.1161/01.STR.0000087172.16305.CD.

Perrochon A, Borel B, Istrate D, Compagnat M, Daviet JC. Exercise-based games interventions at home in individuals with a neurological disease: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Ann Phys Rehabil Med. 2019;62(5):366–78. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.rehab.2019.04.004.

Islam MK, Brunner I. Cost-analysis of virtual reality training based on the virtual reality for upper extremity in subacute stroke (VIRTUES) trial. Int J Technol Assess Health Care. 2019;35(5):373–8. https://doi.org/10.1017/S026646231900059X.

Duret C, Grosmaire AG, Krebs HI. Robot-assisted therapy in upper extremity hemiparesis: overview of an evidence-based approach. Front Neurol. 2019;10:412. https://doi.org/10.3389/fneur.2019.00412.

Lee SH, Jung H-Y, Yun SJ, Oh B-M, Seo HG. Upper extremity rehabilitation using fully immersive virtual reality games with a head mount display: a feasibility study. J Injury Funct Rehabil. 2020;12:257–62. https://doi.org/10.1002/pmrj.12206.

Mehrholz J. Is electromechanical and robot-assisted arm training effective for improving arm function in people who have had a stroke: a cochrane review. Am J Phys Med Rehabil. 2019;98(4):339–40. https://doi.org/10.1097/phm.0000000000001133.

Veerbeek JM, Langbroek-Amersfoort AC, van Wegen EE, Meskers CG, Kwakkel G. Effects of robot-assisted therapy for the upper limb after stroke. Neurorehabil Neural Repair. 2017;31(2):107–21. https://doi.org/10.1177/1545968316666957.

Laver KE, Adey-Wakeling Z, Crotty M, Lannin NA, George S, Sherrington C. Telerehabilitation services for stroke. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2020;1:010255. https://doi.org/10.1002/14651858.CD010255.pub3.

Maier M, Rubio Ballester B, Duff A, Duarte Oller E, Verschure PFMJ. Effect of specific over nonspecific VR-based rehabilitation on poststroke motor recovery: a systematic meta-analysis. Neurorehabil Neural Repair. 2019;33(2):112–29. https://doi.org/10.1177/1545968318820169.

Aminov, et al. What do randomized controlled trials say about virtual rehabilitation in stroke? A systematic literature review and meta-analysis of upper-limb and cognitive outcomes. J Neuroeng Rehabil. 2018;15(1):29. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12984-018-0370-2.

Hung JW, Chou CX, Chang YJ, et al. Comparison of Kinect2Scratch game-based training and therapist-based training for the improvement of upper extremity functions of patients with chronic stroke: a randomized controlled single-blinded trial. Eur J Phys Rehabil Med. 2019;55(5):542–50. https://doi.org/10.23736/S1973-9087.19.05598-9.

Dehem S, Montedoro V, Edwards MG, et al. Development of a robotic upper limb assessment to configure a serious game. NeuroRehabilitation. 2019;44(2):263–74. https://doi.org/10.3233/NRE-182525.

Hocine N, Gouaïch A, Cerri SA, et al. Adaptation in serious games for upper-limb rehabilitation: an approach to improve training outcomes. User Model User-Adap Inter. 2015;25:65–98. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11257-015-9154-6.

Maier M, Ballester BR, Verschure PFMJ. Principles of neurorehabilitation after stroke based on motor learning and brain plasticity mechanisms. Front Syst Neurosci. 2019;13:74. https://doi.org/10.3389/fnsys.2019.00074.

Oh YB, Kim GW, Han KS, et al. Efficacy of virtual reality combined with real instrument training for patients with stroke: a randomized controlled trial. Arch Phys Med Rehabil. 2019;100(8):1400–8. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.apmr.2019.03.013.

Karamians R, Proffitt R, Kline D, Gauthier LV. Effectiveness of virtual reality- and gaming-based interventions for upper extremity rehabilitation poststroke: a meta-analysis. Arch Phys Med Rehabil. 2019. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.apmr.2019.10.195.

World Health Organization. International classification of functioning, disability and health: ICF. World Health Organization. 2001. https://apps.who.int/iris/handle/10665/42407.

Moher D, Liberati A, Tetzlaff J, Altman DG, The PRISMA Group. Preferred reporting items for systematic reviews and meta-analyses: the PRISMA statement. BMJ. 2009;2009(339):b2535. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmj.b2535.

de Morton NA. The PEDro scale is a valid measure of the methodological quality of clinical trials: a demographic study. Aust J Physiother. 2009;55(2):129–33. https://doi.org/10.1016/s0004-9514(09)70043-1.

Higgins JP, Altman DG, Gøtzsche PC, et al. The Cochrane Collaboration’s tool for assessing risk of bias in randomised trials. BMJ. 2011;343:d5928. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmj.d5928.

Stinear CM, Lang CE, Zeiler S, Byblow WD. Advances and challenges in stroke rehabilitation. Lancet Neurol. 2020;19(4):348–60. https://doi.org/10.1016/S1474-4422(19)30415-6.

Kwakkel G, Lannin NA, Borschmann K, English C, Ali M, Churilov L, Bernhardt J. Standardized measurement of sensorimotor recovery in stroke trials: consensus-based core recommendations from the stroke recovery and rehabilitation roundtable. Int J Stroke. 2017;12(5):451–61. https://doi.org/10.1177/1747493017711813.

Alt Murphy M, Resteghini C, Feys P, Lamers I. An overview of systematic reviews on upper extremity outcome measures after stroke. BMC Neurol. 2015;15:29. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12883-015-0292-6.

Fugl-Meyer AR, Jaasko L, Leyman I, Olsson S, Steglind S. The post-stroke hemiplegic patient. 1. A method for evaluation of physical performance. Scand J Rehabil Med. 1975;7(1):13–31.

Yozbatiran N, Der-Yeghiaian L, Cramer SC. A standardized approach to performing the action research arm test. Neurorehabil Neural Repair. 2008;22(1):78–90. https://doi.org/10.1177/1545968307305353.

Mathiowetz V, Volland G, Kashman N, Weber K. Adult norms for the box and block test of manual dexterity. Am J Occup Ther. 1985;39(6):386–91. https://doi.org/10.5014/ajot.39.6.386.

Wolf SL, Catlin PA, Ellis M, Archer AL, Morgan B, Piacentino A. Assessing wolf motor function test as outcome measure for research in patients after stroke. Stroke. 2001;32(7):1635–9. https://doi.org/10.1161/01.str.32.7.1635.

Duncan PW, Wallace D, Lai SM, Johnson D, Embretson S, Laster LJ. The stroke impact scale version 2..0 Evaluation of reliability, validity, and sensitivity to change. Stroke. 1999;30(10):2131–40. https://doi.org/10.1161/01.str.30.10.2131.

Higgins JPT, Thomas J, Chandler J, Cumpston M, Li T, Page MJ, Welch VA (editors). Cochrane handbook for systematic reviews of interventions version 6.0 (updated July 2019). Cochrane, 2019.

Kottink AI, Prange GB, Krabben T, Rietman JS, Buurke JH. Gaming and conventional exercises for improvement of arm function after stroke: a randomized controlled pilot study. Games Health J. 2014;3(3):184–91. https://doi.org/10.1089/g4h.2014.0026.

Park M, Ko MH, Oh SW, Lee JY, Ham Y, Yi H, Shin JH. Effects of virtual reality-based planar motion exercises on upper extremity function, range of motion, and health-related quality of life: a multicenter, single-blinded, randomized, controlled pilot study. J Neuroeng Rehabil. 2019;16(1):122. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12984-019-0595-8.

Wan X, Wang W, Liu J, Tong T. Estimating the sample mean and standard deviation from the sample size, median, range and/or interquartile range. BMC Med Res Methodol. 2014;14:135. https://doi.org/10.1186/1471-2288-14-135.

Armijo-Olivo S, da Costa BR, Cummings GG, Ha C, Fuentes J, Saltaji H, Egger M. PEDro or cochrane to assess the quality of clinical trials? A meta-epidemiological study. PLoS ONE. 2015;10(7):e0132634. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0132634.

Review Manager Web (RevMan Web). The Cochrane Collaboration, 2019. revman.cochrane.org.

DerSimonian R, Laird N. Meta-analysis in clinical trials. Control Clin Trials. 1986;7(3):177–88. https://doi.org/10.1016/0197-2456(86)90046-2.

GRADEpro GDT: GRADEpro guideline development tool [Software]. McMaster University, 2015 (developed by Evidence Prime, Inc.). Available from gradepro.org

Norouzi-Gheidari N, Hernandez A, Archambault PS, Higgins J, Poissant L, Kairy D. Feasibility, safety and efficacy of a virtual reality exergame system to supplement upper extremity rehabilitation post-stroke: a pilot randomized clinical trial and proof of principle. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2019;17(1):113. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph17010113.

Brunner I, Skouen JS, Hofstad H, et al. Virtual reality training for upper extremity in subacute stroke (VIRTUES): a multicenter RCT. Neurology. 2017;89(24):2413–21. https://doi.org/10.1212/WNL.0000000000004744.

Saposnik G, Levin M, Outcome Research Canada (SORCan) Working Group. Virtual reality in stroke rehabilitation: a meta-analysis and implications for clinicians. Stroke. 2011;42(5):1380–6. https://doi.org/10.1161/STROKEAHA.110.605451.

Palma GC, Freitas TB, Bonuzzi GM, et al. Effects of virtual reality for stroke individuals based on the international classification of functioning and health: a systematic review. Top Stroke Rehabil. 2017;24(4):269–78. https://doi.org/10.1080/10749357.2016.1250373.

Lohse KR, Hilderman CG, Cheung KL, Tatla S, Van der Loos HF. Virtual reality therapy for adults post-stroke: a systematic review and meta-analysis exploring virtual environments and commercial games in therapy. PLoS ONE. 2014;9(3):e93318. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0093318.

Laffont I, Froger J, Jourdan C, et al. Rehabilitation of the upper arm early after stroke: video games versus conventional rehabilitation. A randomized controlled trial. Ann Phys Rehabil Med. 2020;63(3):173–80. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.rehab.2019.10.009.

da Silva CM, Bermúdez I Badia S, Duarte E, Verschure PF. Virtual reality based rehabilitation speeds up functional recovery of the upper extremities after stroke: a randomized controlled pilot study in the acute phase of stroke using the rehabilitation gaming system. Restor Neurol Neurosci. 2011;29(5):287–98. https://doi.org/10.3233/RNN-2011-0599.

Kiper P, Szczudlik A, Agostini M, et al. Virtual reality for upper limb rehabilitation in subacute and chronic stroke: a randomized controlled trial. Arch Phys Med Rehabil. 2018;99(5):834-842.e4. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.apmr.2018.01.023.

Piron L, Turolla A, Agostini M, et al. Motor learning principles for rehabilitation: a pilot randomized controlled study in poststroke patients. Neurorehabil Neural Repair. 2010;24(6):501–8. https://doi.org/10.1177/1545968310362672.

Carpinella I, Lencioni T, Bowman T, et al. Effects of robot therapy on upper body kinematics and arm function in persons post stroke: a pilot randomized controlled trial. J Neuroeng Rehabil. 2020;17(1):10. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12984-020-0646-1.

Gottesman RF, Hillis AE. Predictors and assessment of cognitive dysfunction resulting from ischaemic stroke. Lancet Neurol. 2010;9(9):895–905. https://doi.org/10.1016/S1474-4422(10)70164-2.

Langhorne P, Bernhardt J, Kwakkel G. Stroke rehabilitation. Lancet. 2011;377(9778):1693–702. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0140-6736(11)60325-5.

Adomavičienė A, Daunoravičienė K, Kubilius R, Varžaitytė L, Raistenskis J. Influence of new technologies on post-stroke rehabilitation: a comparison of armeo spring to the kinect system. Medicina (Kaunas). 2019. https://doi.org/10.3390/medicina5504009.

Ang KK, Guan C, Phua KS, Wang C, Zhou L, Tang KY, Chua KS. Brain-computer interface-based robotic end effector system for wrist and hand rehabilitation: results of a three-armed randomized controlled trial for chronic stroke. Front Neuroeng. 2014;7:30. https://doi.org/10.3389/fneng.2014.00030.

Aprile I, Germanotta M, Cruciani A, Loreti S, Pecchioli C, Cecchi F, Montesano A, Galeri S, Diverio M, Falsini C, Speranza G, Langone E, Papadopoulou D, Padua L, Carrozza MC. FDG robotic rehabilitation group. Upper limb robotic rehabilitation after stroke: a multicenter, randomized clinical trial. J Neurol Phys Ther. 2020;44(1):3-14. https://doi.org/10.1097/NPT.0000000000000295.

Aşkın A, Atar E, Kocyiğit H, Tosun A. Effects of Kinect-based virtual reality game training on upper extremity motor recovery in chronic stroke. Somatosens Mot Res. 2018;35(1):25–32. https://doi.org/10.1080/08990220.2018.1444599.

da Silva Cameirao M, Bermudez I Badia S, Duarte E, Verschure PF. Virtual reality based rehabilitation speeds up functional recovery of the upper extremities after stroke: a randomized controlled pilot study in the acute phase of stroke using the rehabilitation gaming system. Restor Neurol Neurosci. 2011;29(5):287–98. https://doi.org/10.3233/rnn-2011-0599.

Cameirao MS, Badia SB, Duarte E, Frisoli A, Verschure PF. The combined impact of virtual reality neurorehabilitation and its interfaces on upper extremity functional recovery in patients with chronic stroke. Stroke. 2012;43(10):2720–8. https://doi.org/10.1161/STROKEAHA.112.653196.

Cho KH, Song WK. Robot-assisted reach training with an active assistant protocol for long-term upper extremity impairment poststroke: a randomized controlled trial. Arch Phys Med Rehabil. 2019;100(2):213–9. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.apmr.2018.10.002.

Choi YH, Ku J, Lim H, Kim YH, Paik NJ. Mobile gamebased virtual reality rehabilitation program for upper limb dysfunction after ischemic stroke. Restor Neurol Neurosci. 2016;34(3):455–63. https://doi.org/10.3233/rnn-150626.

Crosbie JH, Lennon S, McGoldrick MC, McNeill MD, McDonough SM. Virtual reality in the rehabilitation of the arm after hemiplegic stroke: a randomized controlled pilot study. Clin Rehabil. 2012;26(9):798–806. https://doi.org/10.1177/0269215511434575.

Duff M, Chen Y, Cheng L, Liu SM, Blake P, Wolf SL, Rikakis T. Adaptive mixed reality rehabilitation improves quality of reaching movements more than traditional reaching therapy following stroke. Neurorehabil Neural Repair. 2013;27(4):306–15. https://doi.org/10.1177/1545968312465195.

Henrique PPB, Colussi EL, De Marchi ACB. Effects of exergame on patients’ balance and upper limb motor function after stroke: a randomized controlled trial. J Stroke Cerebrovasc Dis. 2019;28(8):2351–7. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jstrokecerebrovasdis.2019.05.031.

Housman SJ, Scott KM, Reinkensmeyer DJ. A randomized controlled trial of gravity-supported, computer-enhanced arm exercise for individuals with severe hemiparesis. Neurorehabil Neural Repair. 2009;23(5):505–14. https://doi.org/10.1177/1545968308331148.

Jang SH, You SH, Hallett M, Cho YW, Park CM, Cho SH, Kim TH. Cortical reorganization and associated functional motor recovery after virtual reality in patients with chronic stroke: an experimenter blind preliminary study. Arch Phys Med Rehabil. 2005;86(11):2218–23. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.apmr.2005.04.015.

Jo K, Yu J, Jung J. Effects of virtual reality-based rehabilitation on upper extremity function and visual perception in stroke patients: a randomized control trial. J Phys Ther Sci. 2012;24(11):1205–8.

Kim WS, Cho S, Park SH, Lee JY, Kwon S, Paik NJ. A low cost kinect-based virtual rehabilitation system for inpatient rehabilitation of the upper limb in patients with subacute stroke: a randomized, doubleblind, sham-controlled pilot trial. Medicine (Baltimore). 2018;97(25):e11173. https://doi.org/10.1097/md.0000000000011173.

Kiper P, Piron L, Turolla A, Stożek J, Tonin P. The effectiveness of reinforced feedback in virtual environment in the first 12 months after stroke. Neurol Neurochir Pol. 2011;45(5):436–44. https://doi.org/10.1016/s0028-3843(14)60311-x.

Kiper P, Agostini M, Luque-Moreno C, Tonin P, Turolla A. Reinforced feedback in virtual environment for rehabilitation of upper extremity dysfunction after stroke: preliminary data from a randomized controlled trial. Biomed Res Int. 2014;2014:752128. https://doi.org/10.1155/2014/752128.

Klamroth-Marganska V, Blanco J, Campen K, Curt A, Dietz V, Ettlin T, Riener R. Three-dimensional, task-specific robot therapy of the arm after stroke: a multicentre, parallel-group randomised trial. Lancet Neurol. 2014;13(2):159–66. https://doi.org/10.1016/S1474-4422(13)70305-3.

Kwon JS, Park MJ, Yoon IJ, Park SH. Effects of virtual reality on upper extremity function and activities of daily living performance in acute stroke: a double-blind randomized clinical trial. NeuroRehabilitation. 2012;31(4):379–85. https://doi.org/10.3233/nre-2012-00807.

Lee M, Son J, Kim J, Pyun S-B, Eun S-D, Yoon B. Comparison of individualized virtual reality- and group-based rehabilitation in older adults with chronic stroke in community settings: a pilot randomized controlled trial. Eur J Integr Med. 2016;8(5):738–46. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.eujim.2016.08.166.

Lee S, Kim Y, Lee BH. Effect of virtual reality-based bilateral upper extremity training on upper extremity function after stroke: a randomized controlled clinical trial. Occup Ther Int. 2016;23(4):357–68. https://doi.org/10.1002/oti.1437.

Lee MJ, Lee JH, Lee SM. Effects of robot-assisted therapy on upper extremity function and activities of daily living in hemiplegic patients: a single-blinded, randomized, controlled trial. Technol Health Care. 2018;26(4):659–66. https://doi.org/10.3233/THC-181336.

Levin MF, Snir O, Liebermann DG, Weingarden H, Weiss PL. Virtual reality versus conventional treatment of reaching ability in chronic stroke: clinical feasibility study. Neurol Ther. 2012;1(1):3. https://doi.org/10.1007/s40120-012-0003-9.

Liao WW, Wu CY, Hsieh YW, Lin KC, Chang WY. Effects of robot-assisted upper limb rehabilitation on daily function and realworld arm activity in patients with chronic stroke: a randomized controlled trial. Clin Rehabil. 2012;26(2):111–20. https://doi.org/10.1177/0269215511416383.

Mugler EM, Tomic G, Singh A, Hameed S, Lindberg EW, Gaide J, Slutzky MW. Myoelectric computer interface training for reducing co-activation and enhancing arm movement in chronic stroke survivors: a randomized trial. Neurorehabil Neural Repair. 2019;33(4):284–95. https://doi.org/10.1177/1545968319834903.

Nijenhuis SM, Prange-Lasonder GB, Stienen AH, Rietman JS, Buurke JH. Effects of training with a passive hand orthosis and games at home in chronic stroke: a pilot randomised controlled trial. Clin Rehabil. 2017;31(2):207–16. https://doi.org/10.1177/0269215516629722.

Ogun MN, Kurul R, Yaşar MF, Turkoglu SA, Avci Ş, Yildiz N. Effect of leap motion-based 3D immersive virtual reality usage on upper extremity function in ischemic stroke patients. Arq Neuropsiquiatr. 2019;77(10):681–8. https://doi.org/10.1590/0004-282x20190129.

Piron L, Turolla A, Agostini M, Zucconi C, Cortese F, Zampolini M, Tonin P. Exercises for paretic upper limb after stroke: a combined virtual-reality and telemedicine approach. J Rehabil Med. 2009;41(12):1016–102. https://doi.org/10.2340/16501977-0459.

Prange GB, Kottink AI, Buurke JH, Eckhardt MM, van Keulen- Rouweler BJ, Ribbers GM, Rietman JS. The effect of arm support combined with rehabilitation games on upper-extremity function in subacute stroke: a randomized controlled trial. Neurorehabil Neural Repair. 2015;29(2):174–82. https://doi.org/10.1177/1545968314535985.

Rogers JM, Duckworth J, Middleton S, Steenbergen B, Wilson PH. Elements virtual rehabilitation improves motor, cognitive, and functional outcomes in adult stroke: evidence from a randomized controlled pilot study. J Neuroeng Rehabil. 2019;16(1):56. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12984-019-0531-y.

Schuster-Amft C, Eng K, Suica Z, Thaler I, Signer S, Lehmann I, Kiper D. Effect of a four-week virtual reality-based training versus conventional therapy on upper limb motor function after stroke: a multicenter parallel group randomized trial. PLoS ONE. 2018;13(10):e0204455. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0204455.

Shin JH, Ryu H, Jang SH. A task-specific interactive gamebased virtual reality rehabilitation system for patients with stroke: a usability test and two clinical experiments. J Neuroeng Rehabil. 2014;11:32. https://doi.org/10.1186/1743-0003-11-32.

Shin JH, Bog Park S, Ho Jang S. Effects of game-based virtual reality on health-related quality of life in chronic stroke patients: a randomized, controlled study. Comput Biol Med. 2015;63:92–8. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.compbiomed.2015.03.011.

Shin JH, Kim MY, Lee JY, Jeon YJ, Kim S, Lee S, Choi Y. Effects of virtual reality-based rehabilitation on distal upper extremity function and health-related quality of life: a single-blinded, randomized controlled trial. J Neuroeng Rehabil. 2016;13:17. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12984-016-0125-x.

Subramanian SK, Lourenco CB, Chilingaryan G, Sveistrup H, Levin MF. Arm motor recovery using a virtual reality intervention in chronic stroke: randomized control trial. Neurorehabil Neural Repair. 2013;27(1):13–23. https://doi.org/10.1177/1545968312449695.

Thielbar KO, Lord TJ, Fischer HC, Lazzaro EC, Barth KC, Stoykov ME, Kamper DG. Training finger individuation with a mechatronic-virtual reality system leads to improved fine motor control post-stroke. J Neuroeng Rehabil. 2014;11:171. https://doi.org/10.1186/1743-0003-11-171.

Thielbar KO, Triandafilou KM, Barry AJ, Yuan N, Nishimoto A, Johnson J, Kamper DG. Home-based upper extremity stroke therapy using a multiuser virtual reality environment: a randomized trial. Arch Phys Med Rehabil. 2020;101(2):196–203. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.apmr.2019.10.182.

Tomic TJ, Savic AM, Vidakovic AS, Rodic SZ, Isakovic MS, Rodriguez-de-Pablo C, Konstantinovic LM. ArmAssist robotic system versus matched conventional therapy for poststroke upper limb rehabilitation: a randomized clinical trial. Biomed Res Int. 2017;2017:7659893. https://doi.org/10.1155/2017/7659893.

Wolf SL, Sahu K, Bay RC, Buchanan S, Reiss A, Linder S, Alberts J. The HAAPI (home arm assistance progression initiative) trial: a novel robotics delivery approach in stroke rehabilitation. Neurorehabil Neural Repair. 2015;29(10):958–68. https://doi.org/10.1177/1545968315575612.

Yin CW, Sien NY, Ying LA, Chung SF, Tan May Leng D. Virtual reality for upper extremity rehabilitation in early stroke: a pilot randomized controlled trial. Clin Rehabil. 2014;28(11):1107–14. https://doi.org/10.1177/0269215514532851.

Zondervan DK, Friedman N, Chang E, Zhao X, Augsburger R, Reinkensmeyer DJ, Cramer SC. Home-based hand rehabilitation after chronic stroke: randomized, controlled single-blind trial comparing the MusicGlove with a conventional exercise program. J Rehabil Res Dev. 2016;53(4):457–72. https://doi.org/10.1682/jrrd.2015.04.0057.

Acknowledgements

We would like to thank the Région Wallonne, the SPW-Economie-Emploi-Recherche and the Win 2 Wal Program (convention n°1810108) for their support. We would like to thank Christine Detrembleur, professor at UCLouvain, for her availability and guidance regarding the data analyses aspects. Also, we would like to thank Sophie Patris, professional librarian at UCLouvain, for her help in the elaboration of the search strategy.

Funding

Région Wallonne, SPW-Economie-Emploi-Recherche, Win2Wal Program (convention n°1810108).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

ID and GE conducted the study selection process, retrieved data and performed analyses. GE contributed to writing the manuscript. TL and SD contributed to data interpretation and manuscript revisions. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

Not applicable.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary Information

Additional file 1: Table S1.

Detailed PEDro scale scoring for each study. Figure S1. Detailed analysis using the Cochrane collaboration risk of bias tool. Figure S2. Detailed summary of findings using the GRADEpro approach. Figure S3. Funnel plot graphical representation. Figure S4. Sensitivity analysis without outliers. Figure S5. Sensitivity analysis: use of different correlation coefficient value (0.9). Forest plot of upper limb motor function as measured by the FMA-UE: studies using a serious game fulfilling ≥ 8 Npr versus studies using a serious game fulfilling < 8 Npr. Abbreviations; FMA-UE, upper extremity subscale of the Fugl Meyer Assessment; Npr, Neurorehabilitation principles. Figure S6. Forest plot of upper limb activity as measured by the ARAT, BBT, WMFT: studies in the subacute phase after stroke versus studies in the chronic phase after stroke. Abbreviations; ARAT, Action Research Arm Test; BBT, Box and Block test; WMFT, Wolf Motor Function Test; Npr, Neurorehabilitation principles. Figure S7. Follow-up evaluation. Forest plot of upper limb motor function as measured by the FMA-UE: studies using a serious game fulfilling ≥ 8 Npr versus studies using a serious game fulfilling < 8 Npr. Abbreviations; FMA-UE, upper extremity subscale of the Fugl Meyer Assessment; Npr, Neurorehabilitation principles. Figure S8. Follow-up evaluation. Forest plot of upper limb activity as measured by the ARAT, BBT, WMFT: studies using a serious game fulfilling ≥ 8 Npr versus studies using a serious game fulfilling < 8 Npr. Abbreviations; ARAT, Action Research Arm Test; BBT, Box and Block test; WMFT, Wolf Motor Function Test; Npr, Neurorehabilitation principles. Figure S9. Follow-up evaluation. Forest plot of participation as measured by the social participation subscale of the SIS. Abbreviations; SIS, Stroke Impact Scale.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/. The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver (http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/) applies to the data made available in this article, unless otherwise stated in a credit line to the data.

About this article

Cite this article

Doumas, I., Everard, G., Dehem, S. et al. Serious games for upper limb rehabilitation after stroke: a meta-analysis. J NeuroEngineering Rehabil 18, 100 (2021). https://doi.org/10.1186/s12984-021-00889-1

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s12984-021-00889-1