Abstract

Background

The use of neurorobotic devices may improve gait recovery by entraining specific brain plasticity mechanisms, which may be a key issue for successful rehabilitation using such approach. We assessed whether the wearable exoskeleton, Ekso™, could get higher gait performance than conventional overground gait training (OGT) in patients with hemiparesis due to stroke in a chronic phase, and foster the recovery of specific brain plasticity mechanisms.

Methods

We enrolled forty patients in a prospective, pre-post, randomized clinical study. Twenty patients underwent Ekso™ gait training (EGT) (45-min/session, five times/week), in addition to overground gait therapy, whilst 20 patients practiced an OGT of the same duration. All individuals were evaluated about gait performance (10 m walking test), gait cycle, muscle activation pattern (by recording surface electromyography from lower limb muscles), frontoparietal effective connectivity (FPEC) by using EEG, cortico-spinal excitability (CSE), and sensory-motor integration (SMI) from both primary motor areas by using Transcranial Magnetic Stimulation paradigm before and after the gait training.

Results

A significant effect size was found in the EGT-induced improvement in the 10 m walking test (d = 0.9, p < 0.001), CSE in the affected side (d = 0.7, p = 0.001), SMI in the affected side (d = 0.5, p = 0.03), overall gait quality (d = 0.8, p = 0.001), hip and knee muscle activation (d = 0.8, p = 0.001), and FPEC (d = 0.8, p = 0.001). The strengthening of FPEC (r = 0.601, p < 0.001), the increase of SMI in the affected side (r = 0.554, p < 0.001), and the decrease of SMI in the unaffected side (r = − 0.540, p < 0.001) were the most important factors correlated with the clinical improvement.

Conclusions

Ekso™ gait training seems promising in gait rehabilitation for post-stroke patients, besides OGT. Our study proposes a putative neurophysiological basis supporting Ekso™ after-effects. This knowledge may be useful to plan highly patient-tailored gait rehabilitation protocols.

Trial registration

Similar content being viewed by others

Background

Most of the patients with stroke experience a restriction of their mobility. Gait impairment after stroke mainly depends on deficits in functional ambulation capacity, balance, walking velocity, cadence, stride length, and muscle activation pattern, resulting in a longer gait cycle duration and lower than normal stance/swing ratio in the affected side, paralleled by a shorter gait cycle duration and a higher than normal stance/swing ratio in the unaffected side [1].

Conventional gait training often offers non-completely satisfactory results. Specifically, patients with stroke receiving intensive gait training with or without body weight support (BWS) may not improve in walking ability more than those who are not receiving the same treatment (with the exception of walking speed and endurance) [2,3,4,5]. Moreover, only patients with stroke who are able to walk benefit most from such an intervention [2,3,4,5]. Therefore, there is growing effort to increase the efficacy of gait rehabilitation for stroke patients by using advanced technical devices. Neurorobotic devices, including robotic-assisted gait training (RAGT) with BWS, result in a more likely achievement of independent walking when coupled with overground gait training (OGT) in patients with stroke. Specifically, RAGT combined with OGT has an additional beneficial effect on functional ambulation outcomes, although depending on the duration and intensity of RAGT [6, 7]. Further, RAGT requires a more active subject participation in gait training as compared to the traditional OGT, which is a vital feature of gait rehabilitation [7, 8].

Even though no substantial differences have been reported among the different types of RAGT devices [9], a main problem with neurorobotic devices is the provision for the patient of a real-world setting ambulation [10, 11]. To this end, wearable powered exoskeletons, e.g., the Ekso™ (Ekso™ Bionics, Richmond, CA, USA), have been designed to improve OGT in neurologic patients.

Notwithstanding, the efficacy of wearable powered exoskeletons in improving functional ambulation capacity (including gait pattern, step length, walking speed and endurance, balance and coordination) has not been definitively proven, and any further benefit in terms of gait performance remains to be confirmed. However, a recent study showed that Ekso™ could improve functional ambulation capacity in patients with sub-acute and chronic stroke [12]. Therefore, a first aim of our study was to assess whether Ekso™ is useful in improving functional ambulation capacity and gait performance in chronic post-stroke patients compared to conventional OGT.

The neurophysiologic mechanisms harnessed by powered exoskeletons to favor the recovery of functional ambulation capacity are still unclear. It is argued that the efficacy of neurorobotics in improving functional ambulation capacity depends on the high frequency and intensity of repetition of task-oriented movements [13]. This could guarantee a potentially stronger entrainment of the neuroplasticity mechanisms related to motor learning and function recovery following brain injury, including sensorimotor plasticity, frontoparietal effective connectivity (FPEC), and transcallosal inhibition, as compared to conventional therapy [14,15,16]. Moreover, the generation and strengthening of new connections supporting the learned behaviors, and the steady recruitment of these neural connections as preferential to the learned behaviors occur through these mechanisms, thus making the re-learned abilities long lasting [13, 14, 17,18,19,20,21,22,23].

Such neurophysiologic mechanisms have been tested in neurorobotic rehabilitation using stationary exoskeletons (e.g. Lokomat™) [13, 14]. Therefore, the second aim of our study was to assess whether there are specific neurophysiological mechanisms (among those related to sensorimotor plasticity, FPEC, and transcallosal inhibition) by which Ekso™ improves functional ambulation capacity in the chronic post-stroke phase. The importance of knowing these mechanisms is remarkable in order to implement patient-tailored rehabilitative training, given that any further advance in motor function recovery mainly relies on motor rehabilitation training, whereas spontaneous motor recovery occurs within 6 months of a stroke [24]. This is also the reason why we focused our study on patients with chronic stroke.

Methods

Patients

Eligible patients were selected among those who attended our Neurorobotic Rehabilitation Unit between May and August, 2017. They had to be aged ≥55 years (so as to avoid cases of young stroke), suffering from a first, single ischemic supra-tentorial stroke (that is a simple and basic model to study plasticity mechanisms following a stroke) occurred more than six months before the study inclusion, with a Muscle Research Council score of ≤3, a Mini-Mental State Examination of > 24, a Modified Ashworth Scale, MAS, of ≤2 of muscles of hip, knee, and ankle, and a Functional Ambulatory Categories of ≤ 4. Moreover, they had to meet the inclusion/exclusion criteria of the manufacturer’s recommendations. Clinic-demographic characteristics are reported in Table 1. The study was approved by our local Ethics Committee and was registered in ClinicalTrials.gov, NCT03162263. All participants gave their written informed consent to individual patient data reporting before participating in the study.

Study design

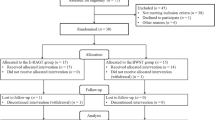

The present study was designed as a randomized clinical trial (prospective, assessor blinded, parallel group study). Forty out of 58 outpatients attending the Neurorobotic Rehabilitation Unit of our Institute were rated as eligible according to the abovementioned inclusion and exclusion criteria and were included in the study (Fig. 1).

The sample size estimate was based on extrapolations from previous studies examining the effects of exoskeletons on gait in patients with stroke [25,26,27,28,29]. Accordingly, we used the effect size (0.9) of the primary composite endpoint for calculations. Power was set at 80%, alpha at 5%; we accounted for a dropout rate of 10%. Using a relatively conservative estimation, a total of 40 subjects (20 per arm) would be required to detect a difference in the primary outcome getting the Minimally Clinically Important Difference (MCID) at the end of the training, assuming non-inferiority with moderate correlations among covariates (R-squared = 0.5).

The enrolled patients were equally randomized into the EGT or the OGT group, with a 1:1 allocation ratio. For randomization, sealed envelopes were prepared in advance and marked on the inside with a + (EGT) or – (OGT). Both the groups were provided with conventional physiotherapy training (including a 15-min warm-up and cool-down period), scheduled in five sessions per week for eight consecutive weeks, 60 min for each session. In addition to conventional physiotherapy training, EGT patients practiced 45-min session of Ekso™ training, while OGT patients underwent 45-min of conventional gait training, for all 8 weeks.

Before the training (TPRE), we evaluated some clinical parameters (10-m walk test, 10MWT, Rivermead Mobility Index, RMI, and timed up and go test, TUG), gait pattern (by recording surface electromyography –sEMG- from lower limbs), FPEC by using EEG, corticospinal excitability (CSE) and sensory-motor integration (SMI) by using Transcranial Magnetic Stimulation (TMS) paradigm over the affected and unaffected hemisphere. All these measures were repeated after the end of the gait training (TPOST), i.e., 8 weeks after starting the training. The experimenters who collected the various measures of plasticity, those who analyzed the data, and the therapists who performed the clinical tests were blind to patient allocation.

Gait training

Ekso™ is an exoskeleton framework for the lower limbs, equipped with (1) electric motors to power movement for the hip and knee joints, (2) passive spring-loaded ankle joints, (3) foot plates on which the user stands, and (4) a backpack that houses a computer, battery supply, and wired controller (Fig. 2). A rigid backpack is an integral structural component of the exoskeleton, which provides support from the posterior pelvis to the upper back, besides carrying the computer and batteries. The exoskeleton attaches to the user’s body with straps over the dorsum of the foot, anterior shin and thigh, abdomen, and anterior shoulders. The limb and pelvic segments are adjustable to the user’s leg and thigh length, and the segment across the pelvis is adjustable for hip width and hip abduction angle.

The user can stand up, sit down, and walk with the help of a front-wheeled walker and with the exoskeleton attached to a ceiling rail tether. A physical therapist initially provides assistance to maintain the user’s center of mass over the base of support to prevent falling (Fig. 2). At first, steps are initiated one at a time by the instructor, as the user is guided to a position of stance on one foot. The onboard computer coordinates the knee and hip movement needed, given the user’s physical size characteristics, to achieve the desired step. As the user learns to weight-shift to a stance position, the exoskeleton can be set to trigger steps automatically when the user hits preset targets for forwarding and lateral weight shifts onto the stance leg. Users also progress from standing up, walking, and sitting down with a front-wheeled walker to using Lofstrand crutches. Over time, instructors reduce the level of assistance they provide and increase the duration of walking during a session. An Ekso™-trained physiotherapist supervised patients’ cooperation and participation in the treatment.

The OGT group underwent sessions of assisted over-ground walking. The physiotherapist oversaw the entire session, guiding the patient to travel along the same walking lane used for the EGT group, using their habitual walking device (crutches, rollator), and shoes, and maintaining the same velocity with the Ekso™ device.

Outcome measures

The primary goal was to obtain an improvement in lower limb gait and balance at the end of the training getting the MCID for the 10MWT, RMI, and TUG scales (composite primary outcome). Secondary outcomes consisted of the modifications of FPEC, CSE, and SMI magnitude, overall gait quality, and hip and knee muscle activation.

TMS paradigm

CSE and SMI were probed using TMS pulses with a monophasic pulse configuration and peripheral nerve electric stimuli. Magnetic pulses were delivered to the affected and unaffected leg-M1 [30] using a standard figure-of-eight coil (diameter of each wing, 90 mm) connected with a high-power Magstim200 stimulator (Magstim Co, Ltd.; UK). The intensity of TMS pulses was adjusted to evoke a muscle response in relaxed abductor hallucis (AH) muscle with a peak-to-peak amplitude of approximately 0.5 mV [31]. SMI was studied using the conditioning-test protocol described by Bikmullina and colleagues [32]. Conditioning electrical stimuli (1 ms in duration and a stimulation intensity of 2.5 times the individual’s sensory perception threshold) were delivered to great toe and preceded the TMS test pulses to contralateral leg-M1 of 55 ms. The mean amplitude of 10 conditioned-MEP was expressed as a percentage of the mean amplitude of 10 unconditioned MEP. Then, we applied a 1 Hz-rTMS protocol over the unaffected M1-leg (1000 pulses at an intensity of 90% of the RMT from AH) [33], using the above-mentioned TMS setup. The overall modulation of MEP and SMI amplitude (from both hemispheres) induced immediately (T0), 30 min (T30), and 60 min (T60) after the rTMS protocol application was calculated as the ratio between the maximum and mean value (among T0, T30, and T60) and taken as a measure of CSE modulation.

Effective connectivity

EEG was recorded using a high-input impedance amplifier (referential input noise < 0.5μVrms @ 1÷20,000 Hz, referential input signal range 150-1000mVPP, input impedance >1GΩ, CMRR > 100 dB, 22bit ADC) of Brain Quick SystemPLUS (Micromed; Mogliano Veneto, Italy), wired to an EEG cap equipped with 21 Ag tin disk electrodes, positioned according to the international 10-20 system. An electrooculogram (EOG) (0.3-70 Hz band-pass) was also recorded. The recording occurred in the morning (about 11am) and lasted at least 10 min, with the eyes open (fixing a point in front of the patient). The EEG end EOG were sampled at 512 Hz, filtered at 0.3-70 Hz, and referenced to linked earlobes [34].

EEG recordings contaminated by blinking, eye movements, movements, and other artifacts were rejected off-line by visual inspection and based on independent component analysis (ICA) data.

First, we identified the cortical activations induced by gait training from the EEG recordings by using Low-Resolution Brain Electromagnetic Tomography (LORETA; free release of LORETA-KEY alpha-software) [35,36,37,38,39].

The brain compartment of the three-shell spherical head model used in the LORETA was restricted to the cortical gray matter, Talairach co-registered [28], and had a resolution of 7 mm, thus obtaining 2394 voxels (i.e., equivalent current dipoles). Therefore, it can be assumed that localization accuracy is at worst in the order of 14 mm, given the 7 mm resolution of the current implementation of LORETA-Talairach with 21 electrodes [40]. The voxels of LORETA solutions were collapsed in 7 regions of interest (ROIs) (prefrontal, PF, supplementary motor, SMA, centroparietal, CP, and occipital, O, areas of both hemispheres) [41] determined according to the brain model coded into Talairach space, by using MATLAB.

Then, structural equation modeling (SEM) technique (or path analysis) was employed to measure the effective connectivity (that assesses the causal influence that one brain area, i.e., electrode-group, exerts over another, under the assumption of a given mechanistic model) [42, 43] among the cortical activations induced by gait trainings. SEM combines a network model supporting the putative connections linking sets of cortical activations and the inter-regional covariances of activity (i.e., the degree to which the activities of two or more regions, i.e., electrode-group, are related), to estimate the influence of one region (electrode set) on another through the putative connections linking the sets of (electrode) activation [41]. The network model, supporting inter-regional connectivity employed in our study, was defined according to a previous study and included the abovementioned ROIs [41]. The SEM model that was used began with zero paths and, from-time-to-time, added paths to improve the model’s stability until no further improvement in the model’s stability was found [44]. Therefore, the SEM generates linear equations that describe the relationship between the variables of interest (i.e., ROI activations), which can be described as paths (i.e., vectors indicating the direction of influence) and path-coefficients (i.e., values reflecting the strength of influence). In other words, an x → y path-coefficient indicates by how many SD units the y increases, corresponding to an increase of 1 SD unit of the x [45,46,47,48].

Gait data analysis

An eight-channel wireless sEMG device (BTS; Milan, Italy) was used to record the EMG activity (sampled at 1 kHz, filtered at 5-300 Hz) from eight muscles (both tibialis anterior -TA, soleus -S, rectus femoris -RF, and biceps femoris -BF). The device was also equipped with an accelerometer, which was set at lumbar level, to establish the gait phases. Gait analysis was conducted on a 10-m walkway and two gaits at a self-selected speed were collected. The following gait parameters for both the affected and unaffected lower limbs were measured [49]: (i) step cadence (number of steps per minute); (ii) gait cycle duration (time from one right heel strike -initial contact- to the next one -end of terminal swing); (iii) stance/swing ratio (ratio between stance from heel strike to toe-off, and swing phase duration from toe-off to heel strike); and (iv) the gait quality index, i.e., an overall gait performance score, reflecting an approximate 60:40% distribution of stance:swing phases. The unaffected and affected side values for each parameter were averaged from the two 10-m gaits and were used for subsequent analyses. In addition, the standard deviations (SD) of the gait variables for each participant were also obtained as a measure of gait variability. All parameters were measured before and after the gait training. The EMG signal was analyzed for root-mean-square (RMS) (a temporal parameter estimating muscle activation) to investigate lower-limb muscle activation modified by gait training [50].

Data analysis

Normal distribution and homogeneity of variance of data were assessed by using the Shapiro–Wilks and Levene test, respectively. Baseline differences were assessed by using t-tests. Gait training induced changes in any outcome measure were explored by repeated measures ANOVA or by the Wilcoxon test (W), where appropriate, with the factors group (two levels: EGT and OGT), time (two -TPRE and TPOST- or four levels –TPRE/TPOST, T0, T30, and T60), path-direction and path-coefficients (49 levels). A p-value < 0.05 was considered significant. Conditional on a significant F-value, post-hoc t-tests were performed with Bonferroni correction for multiple comparisons (α = 0.0055). Descriptive analysis was used to evaluate the effect size measures between the two independent groups (Cohen’s d calculation, p-value). Last, we implemented a multiple logistic regression model to calculate the prognostic accuracy of each electrophysiological outcome measure in the prediction of clinical recovery, considering composite primary outcome measure improvement as a dependent variable and electrophysiological outcome measures as predictive (independent) variables.

Results

All participants completed the training without any significant adverse events, except a mild skin bleachable erythema at the thigh and shank strap locations in seven patients of the EGT. Baseline data were normally distributed (p > 0.2) and homogeneous in variance (p > 0.1). Moreover, the two groups showed non-significant baseline differences concerning clinical-demographic, biomechanical, and electrophysiological parameters (all comparisons p > 0.05).

Both groups showed a reduced gait velocity, a high TUG, and a low RMI score, compared to the normative values from healthy controls [51, 52] (Fig. 3). In parallel, they got a low overall gait quality index, a longer than normal gait cycle duration and lower than normal stance/swing ratio in the affected side, paralleled by a shorter than normal gait cycle duration and a higher than normal stance/swing ratio in the unaffected side (Fig. 4). The alteration in velocity, stride length, and cadence were related to the abnormal average RMS values. We found a higher than normal activation of RF (more in the unaffected than affected side), a lower than normal activation of affected BF, a higher than normal activation of unaffected BF, a much lower than normal activation of S (more in the affected than unaffected side), and a lower than normal activation of both TA (Fig. 5). Altogether, these abnormalities in muscle activation led to reduced hip, knee, and ankle flexion during the swing phase, and a decreased extension of the hip during the stance phase.

Primary outcome measures (10MWT 10 m walk test, RMI Rivermead Mobility Index, TUG timed up and go test) assessed at TPRE and TPOST in the two groups (EGT and OGT). Minimally Clinically Important Difference (MCID) and Minimal Detectable Change (MDC) are reported as well. * refer to post-hoc p-values of within-group analysis (significant whether p < 0.016), whereas # refer to p-values of between-group analysis for TPOST-TPRE difference (p < 0.05). Vertical error bars refer to SD

Mean gait parameters of the affected and unaffected lower limbs at baseline (TPRE) and after gait training (TPOST) in Ekso™ (EGT) and overground gait training (OGT). Normative values are reported as well (black horizontal lines). * refer to p-values of within-group analysis (significant whether p < 0.008), whereas # refer to p-values of between-group analysis for TPOST-TPRE difference (p < 0.05). Vertical error bars refer to SD

Mean muscle activity of the paretic (aff) and non-paretic (unaff) muscles (TA tibialis anterior; S soleus; RF rectus femoris; BF biceps femoris) during gait at baseline (TPRE) and after gait training (TPOST) in EGT and OGT. Normative values are reported as well (black horizontal lines). Vertical error bars refer to SD

Regarding neurophysiologic measures at baseline, we found a low MEP amplitude paralleled by a high SMI strength (i.e., conditioned MEP amplitude decrease) in the affected hemisphere, and a low SMI strength (i.e., conditioned MEP amplitude increase) in the unaffected hemisphere (Fig. 6). The rTMS had weak aftereffects, i.e., a mild MEP amplitude increase and a SMI strength decrease in the affected hemisphere, and a mild MEP amplitude decrease and a SMI strength increase in the unaffected hemisphere (Fig. 6). Finally, brain connectivity was characterized by a globally deteriorated effective connectivity among PF, SMA, and CP, paralleled by a hyperconnectivity among CP, O, and SMA (Fig. 8).

rTMS outcome measures assessed at TPRE and TPOST in the two groups (EGT and OGT). Left and right columns illustrate the rTMS findings (MEP -motor evoked potential- and SMI -sensory-motor integration- in the affected -aff- and unaffected -unaff- hemispheres) before and after gait training, respectively. * refer to post-hoc p-values of within-group analysis (significant whether p < 0.008), whereas # refer to p-values of between-group analysis for TPOST-TPRE difference (p < 0.05). Vertical error bars refer to SD

All EGT patients met the composite primary outcome, i.e., getting the MCID for the 10MWT, RMI, and TUG scales at the end of the training (reflecting an improvement in lower limb gait and balance). This was not the case of OGT. Further, patients belonging to EGT got the Minimal Detectable Change (MDC) in each outcome measure, whereas those belonging to OGT did not get the MDC for 10MWT (Fig. 3) (time×group interaction 10MWT F(1,38) = 13, p = 0.001; TUG F(1,38) = 3.5,p = 0.04; RMI F(1,38) = 4.4, p = 0.04). Specifically, there was a large effect size for 10MWT (d = 0.9, p < 0.001) and a mild-to-moderate one for TUG (0.5, p = 0.02) and RMI (0.6, p = 0.03). Indeed, the EGT showed greater changes than OGT, and got the MCID for every primary outcome measure, differently from OGT (Fig. 3).

The more evident clinical improvement in EGT patients was paralleled by a similar enhancement of the gait parameters. Specifically, the gait quality index (time×group F(1,38) = 43, p < 0.001, d = 0.9) and the step cadence (time×group F(1,38) = 17, p < 0.001, d = 0.9) improved more in the EGT than OGT (Fig. 4). Also, we observed a more evident reduction of the gait cycle duration (time×group F(1,38) = 17, p < 0.001, d = 0.9) and a more evident increase in stance/swing ratio (time×group F(1,38) = 8.6, p = 0.008, d = 0.8) in the affected limb in EGT than OGT. In parallel, we found a more evident shortening of gait cycle duration (time×group F(1,38) = 12, p < 0.001, d = 0.9) and a decrease of stance/swing ratio in the unaffected limb (time×group F(1,38) = 14, p < 0.001, d = 0.9) in EGT than OGT.

These changes were associated to the modification of muscle activation (Fig. 5). Gait training significantly modified the EMG averaged amplitudes of both limbs (time×muscle×side×group F(3,114) = 6.8, p < 0.001) but with specific differences among groups and muscles. In particular, the EMG amplitude of paretic muscles over the entire gait cycle at TPOST were affected more in EGT (time×muscle F(3,57) = 4.3, p = 0.007, d = 0.8) than OGT group (time×muscle F(3,57) = 2.8, p = 0.04, d = 0.6), as compared to the non-paretic ones. Specifically, we found a significant RMS decrease in the affected and unaffected RF and the unaffected BF, and a magnitude increase in the affected BF and the affected and unaffected S (Fig. 5; post-hoc p-values significant when p < 0.008). Both TA muscles showed non-significant changes, except a trend to an increased activation in the paretic TA muscle in the EGT group (p = 0.01).

Last, we probed sensorimotor plasticity and CSE by means of TMS to assess whether EGT may harness one or more of the abovementioned mechanisms of plasticity to induce clinical-biomechanical changes. Following rTMS, MEP amplitude in the affected hemisphere increased more in EGT than OGT (time×group F(3,114) = 5.7, p = 0.001; d = 0.8), whilst SMI strength equally decreased (i.e., conditioned MEP amplitude increased) in both groups (time×group p = 0.4), given that SMI strength was different between the groups already at the TPOST baseline. MEP amplitude in the unaffected hemisphere slightly decreased only in the EGT group (time×group F(3,114) = 4, p = 0.01, d = 0.6), whilst SMI strength increased more (i.e., conditioned MEP amplitude decreased) in EGT than OGT (time×group F(3,114) = 5.8, p = 0.001, d = 0.8), despite SMI strength being different between the groups already at the TPOST baseline (Fig. 6). Anyway, such a baseline difference was not correlated with the magnitude of rTMS aftereffects (Fig. 7). Altogether, EGT induced a rebalance of the SMI of the affected and unaffected hemispheres, in parallel to CSE interhemispheric remodulation, whereas OGT acted more on the affected than unaffected hemisphere. The post-hoc t-tests are summarized in Fig. 5 (significant whether p < 0.008).

Effective connectivity data are summarized in Fig. 8. A three-way ANOVA analysis returned a significant time×group×path interaction (F(48,1824) = 1.8, p = 0.001, d = 0.6), suggesting that both groups modified FPEC but differently in extent and time. In detail, only EGT increased PF-SMA connectivity in the unaffected hemisphere (time×group F(1,38) = 4.6, p = 0.03, d = 0.7), the ipsilateral (time×group F(1,38) = 18, p < 0.001, d = 0.9) and contralateral PF-P (time×group F(1,38) = 8.5, p = 0.006, d = 0.8) and the contralateral PF-O connectivity within the unaffected hemisphere (time×group F(1,38) = 7.8, p = 0.008, d = 0.9). EGT induced a more evident improvement in ipsilateral and contralateral PF-CP (time×group F(1,38) = 13, p = 0.001, d = 0.9) and PF-SMA in the affected hemisphere (time×group F(1,38) = 26, p < 0.001, d = 0.9) as compared to OGT. Both groups equally improved the remaining deteriorated connectivities found at baseline (all time×group interactions p > 0.1) and reduced the abnormal hyperconnectivity within SMA, CP, and O ROIs.

Illustrates the connectivity paths at baseline and following gait training (EGT and OGT). Red color indicates a path-coefficient increase (significant whether p < 0.0001), while blue color a decrease at TPOST as compared to TPRE. Line thickness indicates whether the TPOST-TPRE changes were detectable only following EGT –thick-, greater following EGT than OGT –medium- or equally significant in both groups –thin. Legend: l left hemisphere; O occipital areas; CP centroparietal areas; PF prefrontal areas; r right hemisphere; SMA supplementary motor area

Finally, the multiple regression analysis, with composite clinical outcome measure improvement as a dependent variable, indicated the weakening of SMI in the affected hemisphere (OR 8.5, CI 1.86-38.81, p = 0.008, especially in the EGT, Odds 4), the strengthening of SMI in the unaffected hemisphere (OR 36, CI 5.79-223.55, p < 0.001, especially in the EGT, Odds 9), and the recovery of PF-CP connectivity (OR 27, CI 4.56-159.66, p < 0.001, especially in the EGT, Odds 4) as predictive (independent) variables of clinical improvement. Univariate scattergrams are reported in Fig. 9.

Discussion

Ekso™ training safely induced a greater improvement in gait velocity, balance, coordination, and performance than conventional gait training. In fact, patients belonging to EGT group got all primary outcomes (namely, the MCID in 10MWT, TUG, and RMI, with medium-to-large effect size), whereas those belonging to OGT got only an MDC. The fact that only Ekso™ significantly improved 10MWT scores is of non-negligible importance, given that walking speed is a cardinal indicator of post-stroke gait performance [53].

These clinical changes were supported by a wide modification of gait measures, including overall gait quality (improved), stance/swing ratio and gait cycle duration (reduced limb asymmetries), and knee flexion (enhanced, as indicated by the amplitude features of RF and BF muscles).

At baseline, patients showed a lower/higher stance/swing ratio in the affected/unaffected limb and an insufficient knee flexion in the paretic side (due to the low activity of BF) paralleled by an abnormal knee flexion in the unaffected side (due to the high activity of non-paretic RF). These changes in sEMG amplitude (which reflects the recruitment and discharge rates of the active motor units and serves as an index of neuromuscular function) represent a compensatory mechanism that maintains the functioning of the paretic limb by increasing the firing rate of the non-paretic muscles, and are aimed to avoid the single support of the paretic side and to increase forward acceleration [54].

Such abnormal patterns were improved more by EGT than OGT. We may argue that Ekso™ positively affected gait by acting onto the terminal stance phase (which has an important role in the knee kinematic control), given that paretic BF and non-paretic RF activations improved significantly in EGT [55]. However, sEMG improvements were limited to proximal muscle whereas both S and TA did not show significant changes. This may depend on the degree of movements provided by the Ekso, which are greater within hip and knee joints.

Therefore, our work confirms previous data on the importance of Ekso™ as an additional treatment to conventional gait training to improve ambulatory functions in chronic post-stroke patients [12]. Indeed, the authors showed that the hip and the total score of Motricity Index, the Functional Ambulation Category, the walking velocity, the distance covered in six minutes, and the number of patients performing the 6MWT and 10MWT improved significantly with the Ekso™ usage. Different from our work, no changes were observed at the knee level, and the improvements in velocity and distance were below the MCID for stroke patients. Nonetheless, there are some differences between ours and the study by Molteni et al. [12] that could account for such discrepancies, including patient sampling, randomization, number, duration and intensity of sessions (higher in our study), and motor task selection.

Other studies using exoskeletons provided contradicting results in patients with chronic stroke [27], showing that EGT is equivalent to traditional therapy for chronic stroke patients, while sub-acute patients may experience added benefit from EGT [56]. In detail, some trials indicated no significant differences in improvement between wearable exoskeleton and overground training groups concerning gait speed, TUG, 6MWT, and 10MWT [26, 56,57,58,59]. However, some studies used exoskeleton-stationary rather than exoskeleton-overground walking systems. The strengths of the latter as compared to the former are represented by the high degree of freedom of movement, a lesser extent of the constrainment to the sagittal plane of leg movements, the possibility of multidirectional body movements into the space and of navigating over different surfaces, the different amount of sensory information (including visual, proprioceptive, tactile, and vestibular), and the need that the patient actively interfaces with the exoskeleton to control balance and maintain the trunk [12, 60]. It is, therefore, hypothesizable that exoskeleton-overground walking systems provide the patient with a definitely greater motor control stimulation, multisensory plasticity amount, and required effort to perform the gait training [12].

Other studies indicated that wearable exoskeletons led to a greater improvement then conventional gait training in TUG, 6MWT, and 10MWT [28, 61,62,63,64]. Such discrepancies may depend on non-homogeneity in stroke duration, sample clinical-demographic characteristics (e.g., ambulant on ambulant/non-ambulant patients), the device used (AlterG, HAL) and its design (unilateral/bilateral), training period, main walking outcome measures adopted, randomization, and study type (RCT, pre-post study) [27, 56]. Therefore, multicenter randomized controlled trials comparing robotic and conventional over-ground gait training are necessary to confirm that a powered exoskeleton such as the Ekso™ can improve clinical outcome in chronic post stroke patients by finely tuning the gait cycle kinematic.

Our study offers evidence for possible neurophysiological mechanisms harnessed by Ekso™ to induce such clinical improvement. Unilateral brain damage recovery following stroke largely depends on a reshaping of the interhemispheric balance between the CSE and SMI of the affected and unaffected hemispheres mediated by transcallosal inhibition [65,66,67,68], and by adaptive changes in FPEC within PF, SMA, and CP regions, including a hyperconnectivity among SMA, CP, and O regions [69], so as to vicariate the loss of neural pathways and to restore the impaired function. Indeed, such regions are all included in the network models supporting motor planning and execution. They include SMA (that plans the coordination of self-paced movements), PF (that oversee motor planning and initiation of motor execution), and CP areas (that are related to the representation and execution of motor programs) [70,71,72].

Such mechanisms of recovery occur spontaneously and are harnessed by conventional and robotized gait training [14, 15, 73]. However, EGT showed some peculiar neurophysiologic mechanisms. In particular, EGT induced a reshape of CSE of both hemispheres, whereas OGT aftereffects mainly pertained the affected CSE. Moreover, EGT induced a more evident remodulation of SMI between the hemispheres as compared to OGT, given that SMI at TPOST was more balanced following EGT than OGT and that rTMS aftereffects were more evident following EGT than OGT, regardless of the baseline TPOST difference between the groups (that did not affect the magnitude of rTMS aftereffects). These changes were supported by specific variations in FPEC within the unaffected hemisphere, found only in EGT group, with particular regard to the PF-CP and PF-SMA connections, whereas both groups showed an improvement in PF-PF, SMA-CP, CP-CP, and a reduction the of the hyperconnectivity within and toward the posterior regions. Altogether, these effects are in keeping with the specific top-down control of FPEC and the bilateral sensorimotor plasticity exerted by EGT as compared to OGT concerning motor function recovery, with a notable involvement of the unaffected hemisphere [74,75,76]. The significance of the specific modulations of FPEC and of the rebalance between the SMI concerning the clinical-biomechanical improvement is suggested by the strong correlations among the changes in FPEC, SMI balance, and 10MWT. Moreover, FPEC and SMI balance at baseline predicted 10MWT improvement.

The greater magnitude of the neurophysiological changes induced by EGT, as compared to OGT, may depend on the intrinsic properties of such a wearable device, including a different amount of the sensory inputs (including visual, proprioceptive, tactile, and vestibular). Such a variety of bottom-up information during gait training may significantly affect the top-down modulation of FPEC raised by EGT [77].

There are some limitations to acknowledge. The main limitation consists of the lack of long-term follow-up evaluation. Nevertheless, we have acknowledge that the neurophysiologic mechanisms shaped by neurorobotic rehabilitation may make the re-learned abilities long lasting [13, 14, 17,18,19,20,21,22,23], as proven for different RAGT [78]. It is therefore reasonable that powered exoskeletons, including Ekso™, may also offer long-lasting results. This assertion deserves however confirmation in larger follow-up studies, and thus, we have to be cautious in generalizing the results of our study, even though the data are promising.

One may be concerned about the high dose of therapy administered to the patients, which could be a confounding factor when comparing study protocols. However, the dose of the therapy we adopted was the same used in our previous works on RAGT [13, 14].

Conclusions

Our study suggests that Ekso™ could be useful to promote mobility in persons with stroke owing to mechanisms of brain plasticity and connectivity re-modulation that are specifically entrained by the robotic device, as compared to conventional OGT. Characterizing how top-down connectivity and interhemispheric balance are shaped by neurorobotic therapies could be of remarkable importance to implement patient-tailored rehabilitative training.

References

Den Otter AR, Geurts AC, Mulder T, Duysens J. Abnormalities in the temporal patterning of lower extremity muscle activity in hemiparetic gait. Gait Posture. 2007;25:342–52.

Belda-Lois J-M, Mena-del Horno S, Bermejo-Bosch I, et al. Rehabilitation of gait after stroke: a review towards a top-down approach. J Neuroeng Rehabil. 2011;8:66.

Moseley AM, Stark A, Cameron ID. Pollock a treadmill training and body weight support for walking after stroke. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2005;4:CD002840.

States RA, Pappas E, Salem Y. Overground physical therapy gait training for chronic stroke patients with mobility deficits. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2009;3:CD006075.

Mehrholz J, Thomas S. Elsner B treadmill training and body weight support for walking after stroke. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2017;8:CD002840.

Schwartz I, Meiner Z. Robotic-assisted gait training in neurological patients: who may benefit? Ann Biomed Eng. 2015;43(5):1260–9.

Tefertiller C, Pharo B, Evans N, Winchester P. Efficacy of rehabilitation robotics for walking training in neurological disorders: a review. J Rehabil Res Dev. 2013;48:387.

Pennycott A, Wyss D, Vallery H, Klamroth-Marganska V, Riener R. Towards more effective robotic gait training for stroke rehabilitation: a review. J Neuroeng Rehabil. 2012;9:65.

Bing C, Hao M, Lai-Yin Q, Fei G, Kai-Ming C, Sheung-Wai L, Ling Q, Wei-Hsin L. Recent developments and challenges of lower extremity exoskeletons. J Orthop Translat. 2016;5:26–37.

Janice J, Pei FT. Gait training strategies to optimize walking ability in people with stroke: a synthesis of the evidence. Expert Rev Neurother. 2007;7:1417–36.

Bruni MF, Melegari C, De Cola MC, Bramanti A, Bramanti P, Calabrò RS. What does best evidence tell us about robotic gait rehabilitation in stroke patients: a systematic review and meta-analysis. J Clin Neurosci. 2018;48:11–7.

Molteni F, Gasperini G, Gaffuri M, Colombo M, Giovanzana C, Lorenzon C, et al. Wearable robotic exoskeleton for over-ground gait training in sub-acute and chronic hemiparetic stroke patients: preliminary results. Eur J Phys Rehabil Med. 2017;53:676–84.

Calabrò RS, Naro A, Russo M, Leo A, De Luca R, Balletta T, et al. The role of virtual reality in improving motor performance as revealed by EEG: a randomized clinical trial. J Neuroeng Rehabil. 2017;14:53.

Calabrò RS, Cacciola A, Bertè F, Manuli A, Leo A, Bramanti A, Naro A, Milardi D, Bramanti P. Robotic gait rehabilitation and substitution devices in neurological disorders: where are we now? Neurol Sci. 2016;37:503–14.

Takeuchi N, Izumi S. Rehabilitation with post-stroke motor recovery: a review with a focus on neural plasticity. Stroke Res Treat. 2013;2013:128641.

Hara Y. Brain plasticity and rehabilitation in stroke patients. J Nippon Med Sch. 2015;82(1):4–13.

Turner DL, Ramos-Murguialday A, Birbaumer N, Hoffmann U, Luft A. Neurophysiology of robot-mediated training and therapy: a perspective for future use in clinical populations. Front Neurol. 2013;4:184.

Warraich Z, Kleim JA. Neural plasticity: the biological substrate for neurorehabilitation. PM&R. 2010;2(12 Suppl 2):S208–19.

Schmidt RA, Lee TD. Motor control and learning: a behavioral emphasis. Champaign, IL: Human Kinetics Publishers; 2005.

Kleim JA, Jones TA. Principles of experience-dependent neural plasticity: implications for rehabilitation after brain damage. J Speech Lang Hear Res. 2008;51(1):S225–39.

Langhorne P, Bernhardt J, Kwakkel G. Stroke rehabilitation. Lancet. 2011;377(9778):1693–702.

Hosp JA, Luft AR. Cortical plasticity during motor learning and recovery after ischemic stroke. Neural Plast. 2011;2011:871296.

Feydy A, Carlier R, Roby-Brami A, et al. Longitudinal study of motor recovery after stroke: recruitment and focusing of brain activation. Stroke. 2002;33:1610–7.

Jørgensen HS, Nakayama H, Raaschou HO, Vive-Larsen J, Støier M, Olsen TS. Outcome and time course of recovery in stroke. Part II: time course of recovery. The Copenhagen stroke study. Arch Phys Med Rehabil. 1995;76(5):406–12.

Kawamoto H, Taal S, Niniss H, Hayashi T, Kamibayashi K, Eguchi K, Sankai Y. Voluntary motion support control of robot suit HAL triggered by bioelectrical signal for hemiplegia, 32nd annual international conference of the IEEE engineering in medicine and biology society. Buenos Aires: EMBC; 2010.

Stein J, Bishop L, Stein DJ, Wong CK. Gait training with a robotic leg brace after stroke: a randomized controlled pilot study. Am J Phys Med Rehabil. 2014;93:987–94.

Federici S, Meloni F, Bracalenti M, De Filippis ML. The effectiveness of powered, active lower limb exoskeletons in neurorehabilitation: a systematic review. NeuroRehabilitation. 2015;37(3):321–40.

Nilsson A, Vreede KS, Häglund V, Kawamoto H, Sankai Y, Borg J. Gait training early after stroke with a new exoskeleton – the hybrid assistive limb: a study of safety and feasibility. J Neuroeng Rehabil. 2014;11:92.

Watanabe H, Tanaka N, Inuta T, Saitou H, Yanagi H. Locomotion improvement using a hybrid assistive limb in recovery phase stroke patients: a randomized controlled pilot study. Arch Phys Med Rehabil. 2014;95:2006–12.

Sivaramakrishnan A, Tahara-Eckl L, Madhavan S. Spatial localization and distribution of the TMS-related 'hot spot' of the tibialis anterior muscle representation in the healthy and post-stroke motor cortex. Neurosci Lett. 2016;627:30–5.

Kobayashi M, Pascual-Leone A. Transcranial magnetic stimulation in neurology. Lancet Neurol. 2003;2:145–56.

Bikmullina R, Bäumer T, Zittel S, Münchau A. Sensory afferent inhibition within and between limbs in humans. Clin Neurophysiol. 2009;120:610–8.

Naghdi S, Ansari NN, Rastgoo M, Forogh B, Jalaie S, Olyaei G. A pilot study on the effects of low frequency repetitive transcranial magnetic stimulation on lower extremity spasticity and motor neuron excitability in patients after stroke. J Bodyw Mov Ther. 2015;19:616–23.

Wagner J, Solis-Escalante T, Grieshofer P, Neuper C, Müller-Putz G, Scherer R. Level of participation in robotic-assisted treadmill walking modulates midline sensorimotor EEG rhythms in able-bodied subjects. NeuroImage. 2012;63:1203–11.

Basile LF, Yacubian J, Castro CC, Grattaz WF. Widespread electrical cortical dysfunction in schizophrenia. Schizophr Res. 2004;69:255–66.

Fuchs M, Drenckhahn R, Wischmann HA, Wagner M. An improved boundary element method for realistic volume-conductor modeling. IEEE Trans Biomed Eng. 1998;45:980–97.

Fuchs M, Kastner J, Wagner M, Hawes S, Ebersole JS. A standardized boundary element method volume conductor model. Clin Neurophysiol. 2002;113:702–12.

Pascual-Marqui RD, Michel CM, Lehmann D. Low resolution electromagnetic tomography: a new method for localizing electrical activity in the brain. Int J Psychophysiol. 1994;18:49–65.

Yao J, Dewald JP. Evaluation of different cortical source localization methods using simulated and experimental EEG data. NeuroImage. 2005;25:369–82.

Pascual-Marqui RD, Lehmann D, Koenig T, Kochi K, Merlo MCG, Hell D, Koukkou M. Low resolution brain electromagnetic tomography (LORETA) functional imaging in acute, neuroleptic-naive, first-episode, productive schizophrenics. Psychiatry Res. 1999;90(3):169–79.

Babiloni F, Cincotti F, Basilisco A, Maso E, Bufano M, Babiloni C, et al. Frontoparietal cortical networks revealed by structural equation modeling and high resolution EEG during a short term memory task. Neural engineering, conference proceedings 2003.

Friston W, Ungerleider LG, Jezzard P, Turner R. Characterizing modulatory interactions between V1 and V2 in human cortex with i34R.I. Hum Brain Map. 1995;2:211–24.

McIntosh AR, Gonzalez-Lima F. Structural equation modeling and its application to network analysis in functional brain imaging. Hum Brain Map. 1994;2:2–22.

Craggs JG, Price DD, Verne GN, Perlstein WM, Robinson MM. Functional brain interactions that serve cognitive-affective processing during pain and placebo analgesia. NeuroImage. 2007;38(4):720–9.

James GA, Lu ZL, VanMeter JW, Sathian K, Hu XP, Butler AJ. Changes in resting state effective connectivity in the motor network following rehabilitation of upper extremity post-stroke paresis. Top Stroke Rehabil. 2009;16(4):270–81.

Zhuang J, LaConte S, Peltier S, Zhang K, Hu X. Connectivity exploration with structural equation modeling: an fMRI study of bimanual motor coordination. Neurolmage. 2005;25(2):462–70.

Shipley B. Cause and correlation in biology: a User's guide to path analysis, structural equations and causal inference: Cambridge University Press; 2000.

Solodkin A, Hlustik P, Chen EE, Small SL. Fine modulation in network activation during motor execution and motor imagery. Cereb Cortex. 2004;14(11):1246–55.

Jonsdottir J, Recalcati M, Rabuffetti M, Casiraghi A, Boccardi S, Ferrarin M. Functional resources to increase gait speed in people with stroke: strategies adopted compared to healthy controls. Gait Posture. 2009;29:355–9.

Boe SG, Rice CL, Doherty TJ. Estimating contraction level using root mean square amplitude in control subjects and patients with neuromuscular disorders. Arch Phys Med Rehabil. 2008;89(4):711–8.

Hollman JH, McDade EM, Petersen RC. Normative spatiotemporal gait parameters in older adults. Gait Posture. 2011;34(1):111–8.

Oberg T, Karsznia A, Oberg K. Basic gait parameters: reference data for normal subjects, 10-79 years of age. J Rehabil Res Dev. 1993;30(2):210–23.

Dickstein R. Rehabilitation of gait speed after stroke: a critical review of intervention approaches. Neurorehabil Neural Repair. 2008;22(6):649–60.

Boudarham J, Hameau S, Pradon D, Bensmail D, Roche N, Zory R. Changes in electromyographic activity after botulinum toxin injection of the rectus femoris in patients with hemiparesis walking with a stiff-knee gait. J Electromyogr Kinesiol. 2013;23(5):1036–43.

Jung H, Ko C, Kim JS, Lee B, Lim D. Alterations of relative muscle contribution induced by hemiplegia: straight and turning gaits. Int J Precis Eng Man. 2015;16(10):2219–27.

Louie Dennis R, Eng JJ. Powered robotic exoskeletons in poststroke rehabilitation of gait: a scoping review. J Neuroeng Rehabil. 2016;13:53.

Buesing C, Fisch G, O’Donnell M, Shahidi I, Thomas L, Mummidisetty CK, et al. Effects of a wearable exoskeleton stride management assist system (SMA®) on spatiotemporal gait characteristics in individuals after stroke: a randomized controlled trial. J NeuroEng Rehabil. 2015;12:69.

Kawamoto H, Kamibayashi K, Nakata Y, Yamawaki K, Ariyasu R, Sankai Y, et al. Pilot study of locomotion improvement using hybrid assistive limb in chronic stroke patients. BMC Neurol. 2013;13:141.

Hidler J, Nichols D, Pelliccio M, Brady K, Campbell DD, Kahn JH, Hornby TG. Multicenter randomized clinical trial evaluating the effectiveness of the Lokomat in subacute stroke. Neurorehabil Neural Repair. 2009;23(1):5–13.

Israel JF, Campbell DD, Kahn JH, Hornby TG. Metabolic costs and muscle activity patterns during robotic- and therapist-assisted treadmill walking in individuals with incomplete spinal cord injury. Phys Ther. 2006;86:1466–78.

Yoshimoto T, Shimizu I, Hiroi Y, Kawaki M, Sato D, Nagasawa M. Feasibility and efficacy of high-speed gait training with a voluntary driven exoskeleton robot for gait and balance dysfunction in patients with chronic stroke: non-randomized pilot study with concurrent control. Int J Rehabil Res. 2015;38:338–43.

Bortole M, Venkatakrishnan A, Zhu F, Moreno JC, Francisco GE, Pons JL, et al. The H2 robotic exoskeleton for gait rehabilitation after stroke: early findings from a clinical study. J NeuroEng Rehabil. 2015;12:54.

Byl NN. Mobility training using a bionic knee orthosis in patients in a post- stroke chronic state: a case series. J Med Case Rep. 2012;6:216.

Wong CK, Bishop L, Stein J. A wearable robotic knee orthosis for gait training: a case-series of hemiparetic stroke survivors. Prosthetics Orthot Int. 2012;36:113–20.

Grefkes C, Eickhoff SB, Nowak DA, Dafotakis M, Fink GR. Dynamic intra and interhemispheric interactions during unilateral and bilateral hand movements assessed with fMRI and DCM. NeuroImage. 2008a;41:1382–94.

Grefkes C, Nowak DA, Eickhoff SB, Dafotakis M, Kust J, Karbe H, Fink GR. Cortical connectivity after subcortical stroke assessed with functional magnetic resonance imaging. Ann Neurol. 2008b;63:236–46.

Wang L, Yu C, Chen H, Qin W, He Y, Fan F, et al. Dynamic functional reorganization of the motor execution network after stroke. Brain. 2010;133:1224–38.

Priori A, Hallett M, Rothwell JC. Repetitive transcranial magnetic stimulation or transcranial direct current stimulation? Brain Stimulation. 2009;2:241–5.

Boyd LA, Hayward KS, Ward NS, et al. Biomarkers of stroke recovery: consensus-based core recommendations from the stroke recovery and rehabilitation roundtable. Int J Stroke. 2017;12(5):480–93.

Debaere F, Swinnen SP, Beatse E, Sunaert S, Van HP, Duysens J. Brain areas involved in interlimb coordination: a distributed network. NeuroImage. 2001;14:947–58.

Solodkin A, Hlustik P, Chen EE, Small SL. Fine modulation in network activation during motor execution and motor imagery. Cereb Cortex. 2004;14:1246–55.

Walsh RR, Small SL, Chen EE, Solodkin A. Network activation during bimanual movements in humans. NeuroImage. 2008;43:540–53.

Xu Y, Hou Q, Russell SD, et al. Neuroplasticity in post-stroke gait recovery and noninvasive brain stimulation. Neural Regen Res. 2015;10(12):2072–80.

Buetefisch CM. Role of the Contralesional hemisphere in post-stroke recovery of upper extremity motor function. Front Neurol. 2015;6:214.

Bütefisch CM, Wessling M, Netz J, Seitz RJ, Hömberg V. Relationship between interhemispheric inhibition and motor cortex excitability in subacute stroke patients. Neurorehabil Neural Repair. 2008;22:4–21.

Li W, Li Y, Zhu W, Chen X. Changes in brain functional network connectivity after stroke. Neural Regen Res. 2014;9:51–60.

Eng JJ. Strength training in individuals with stroke. Physiother Can. 2004;56:189–201.

Morone G, Iosa M, Bragoni M, De Angelis D, Venturiero V, Coiro P, Riso R, Pratesi L, Paolucci S. Who may have durable benefit from robotic gait training?: a 2-year follow-up randomized controlled trial in patients with subacute stroke. Stroke. 2012;43(4):1140–2.

Acknowledgements

we would like to thank Prof. Anthony Pettignano for having revised English language.

Availability of data and materials

The datasets used and/or analyzed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

AN, RSC, MR, PB: Substantial contributions to the conception and design of the work, and interpretation of data; revising the work critically for important intellectual content; Final approval of the version to be published; Agreement to be accountable for all aspects of the work in ensuring that questions related to the accuracy or integrity of any part of the work are appropriately investigated and resolved. AC, SP, AB, RDL Acquisition and analysis of data; Drafting the work; Final approval of the version to be published; Agreement to be accountable for all aspects of the work in ensuring that questions related to the accuracy or integrity of any part of the work are appropriately investigated and resolved.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

All procedures performed in studies involving human participants were in accordance with the ethical standards of the institutional and/or national research committee and with the 1964 Helsinki declaration and its later amendments or comparable ethical standards. Our Local Ethic Committee approved the study. All the patients gave their written informed consent to study participation.

Consent for publication

All the patients gave their written informed consent for publication of any individual person’s data in any form.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made. The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver (http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/) applies to the data made available in this article, unless otherwise stated.

About this article

Cite this article

Calabrò, R.S., Naro, A., Russo, M. et al. Shaping neuroplasticity by using powered exoskeletons in patients with stroke: a randomized clinical trial. J NeuroEngineering Rehabil 15, 35 (2018). https://doi.org/10.1186/s12984-018-0377-8

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s12984-018-0377-8