Abstract

Background

Accumulation of senescent cells has been associated with pro-inflammatory effects with deleterious consequences in different human diseases. The purpose of this study was to analyze cell senescence in human synovial tissues (ST), and its impact on the pro-inflammatory function of synovial fibroblasts (SF).

Results

The expression of the senescence marker p16INK4a (p16) was analyzed by immunohistochemistry in rheumatoid arthritis (RA), osteoarthritis (OA), and normal ST from variably aged donors. The proportion of p16(+) senescent cells in normal ST from older donors was higher than from younger ones. Although older RA and OA ST showed proportions of senescent cells similar to older normal ST, senescence was increased in younger RA ST compared to age-matched normal ST. The percentage of senescent SA-β-gal(+) SF after 14 days in culture positively correlated with donor’s age. Initial exposure to H2O2 or TNFα enhanced SF senescence and increased mRNA expression of IL6, CXCL8, CCL2 and MMP3 and proteins secretion. Senescent SF show a heightened IL6, CXCL8 and MMP3 mRNA and IL-6 and IL-8 protein expression response upon further challenge with TNFα. Treatment of senescent SF with the senolytic drug fenofibrate normalized IL6, CXCL8 and CCL2 mRNA expression.

Conclusions

Accumulation of senescent cells in ST increases in normal aging and prematurely in RA patients. Senescence of cultured SF is accelerated upon exposure to TNFα or oxidative stress and may contribute to the pathogenesis of synovitis by increasing the production of pro-inflammatory mediators.

Similar content being viewed by others

Background

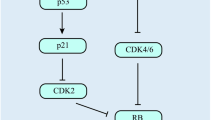

A common factor to aging associated diseases is a chronic, low-grade inflammation, that has been termed “inflammaging” [1, 2]. The cellular basis of this process consists of a cellular pro-inflammatory phenotype, referred to as “senescence-associated secretory phenotype” (SASP), characterized by enhanced production of cytokines, chemokines and matrix metalloproteinases that has been linked to cell senescence [3,4,5]. Senescent cells, characterized by the expression of p16INK4a and irreversible cell-cycle arrest, accumulate in tissues during normal aging, and are thought to contribute to organ dysfunction in different age-associated diseases [6,7,8,9,10]. This concept has been explored in osteoarthritis (OA), a joint disease tightly linked to aging. Increased senescent chondrocytes with a pro-inflammatory SASP phenotype have been demonstrated in OA cartilage and their transplant to normal joints induce joint damage similar to OA [11,12,13,14]. Removal of senescent cells by transgenic technology in an experimental OA model has also demonstrated their deleterious effects, providing the basis for senolysis as a potential therapy in OA [15].

The relationship between aging and arthritis is less clear in other chronic inflammatory joint conditions such as rheumatoid arthritis (RA). Epidemiology of RA shows that its incidence increases with aging, with the sharpest incidence rise between the fourth and sixth decades of life [16]. Aging of the T-cell compartment of the immune system may favor autoimmunity, and this mechanism has been proposed to explain the relationship between aging and RA [17, 18]. However, the potential participation of aging-associated cell changes in the local synovial environment has not been studied. Chronic inflammatory diseases are characterized by increased oxidative stress and ROS production, one of the most relevant contributors to the genomic and mitochondrial damage that characterizes the cellular aging process. It is therefore expected that local cell aging be present in the inflamed synovium. Tissue inflammation and cell senescence have been shown to synergize in the production of pro-inflammatory mediators such as IL-6 that, in turn, activates cellular reprogramming [19]. This reprogramming is interpreted as an attempt to repair tissue damage, but proof of this plasticity in synovitis or other human inflammatory tissues is lacking.

The main resident cells in RA synovial tissue (ST) are synovial fibroblasts (SF) which contribute to the pathogenesis of arthritis by synthesizing a variety of mediators that are very similar to those associated to the SASP, notably IL-6, MMPs and chemokines [20]. Fibroblast senescence has been observed in other normal aged tissues and in pathological tissues such as cancer or fibrosis [21, 22]. In normal skin, fibroblast senescence has been linked to aging and to the acquisition of a matrix degradation and pro-inflammatory phenotype [8, 23]. Here, we describe the accumulation of senescent cells in normal aged and arthritic ST and characterize the phenotype of senescent SF.

Results

p16 and NANOG expression in ST

Nuclear expression of the p16 senescent marker was detected by immunohistochemistry (IHC) in all OA, RA and normal ST groups (Fig. 1a). The proportion of biopsies showing presence of p16(+) cells was higher in RA (37/43, 86%) and OA (13/14, 92.9%) than in normal groups (10/15, 66.7%). Consistent with the older age of OA patients (69.9 ± 5.7 vs 40 ± 16.06 in control group and 54.4 ± 14.3 in RA group), OA synovia showed a significantly higher density of p16(+) cells (Fig. 1b). Since the mean and median age of the healthy donor population were 40 and 44 years old, respectively, we set up a cut-off age of 40 years to dissect the contribution of age to the abundance of p16 and NANOG. Expression of p16 in normal ST was higher in old (age > 40 years old) compared with young (age < 40 years old) donors. Younger RA patients showed a significant increase of p16(+) cell density compared with age-matched healthy donors, whereas older RA patients showed levels similar to the normal controls group (Fig. 1c). Scattered senescent p16(+) cells were observed both through lining and sublining areas in all normal and OA/RA groups. Double immunofluorescent (IF) labelling confirmed that most p16(+) nuclei colocalized to hsp47(+) SF [24] or CD68(+) macrophages (see in Additional file 1: Figure S1).

Expression of p16 and NANOG in ST. a IHC detection of p16 and NANOG in normal, OA and RA ST (Bar 50 μm). b Density of p16(+) and NANOG(+) cells in the different groups (*ANOVA). c Density of p16(+) and NANOG(+) cells in normal and RA ST stratified by age: under (< 40) and over (> 40) 40 years old (*Mann-Whitney)

Expression of the reprogramming marker NANOG, previously shown associated to cell senescence [19], was significantly increased in OA and RA groups compared to normal ST (Fig. 1a and b). No age-related differences in NANOG expression were observed in either normal or in RA ST groups (Fig. 1c).

Cell senescence in cultured SF

Replicative senescence was induced in SF from healthy donors after 14-day culture. Cultured SF usually reached confluence at day 8 after seeding and at day 14 most SF were arrested in G0/G1 phase but significant cell death was not observed (data not shown). To determine the proportion of senescent cells under these conditions in the different groups we detected lysosomal β-galactosidase activity [25, 26] (Fig. 2a). Frequency of SA-β-gal(+) senescent cells in SF cultures increased proportionally to the number of days in culture and was significantly higher at day 14 than at day 5 of culture (Fig. 2b). Under these conditions, we determined the proportion of senescent cells in SF cultures obtained from differently aged healthy donors. The percentage of SA-β-gal(+) cells in 14-day cultures positively correlated with age (r = 0.75/p = 0.008) and was significantly higher in old (> 40 years old) than in young healthy SF (Fig. 2c and d). SF cultures from old arthritic patients (OA or RA) showed a proportion of SA-β-gal(+) that was similar to the similarly aged (> 40 years old) group of healthy donors. Increased senescence of old normal SF compared to younger counterparts was confirmed by the mRNA expression of additional markers of senescence, i. e., enhanced CDKN1A and reduced LMNB1 [27, 28] (Fig. 2e).

Analysis of senescence in 14-day SF cultures. a SA-β-gal activity and DAPI staining. b Time-dependent expansion of SA-β-gal(+) in HSF cultures (n = 4) (*ANOVA). c Correlation between the frequency of SA-β-gal(+) SF and donor’s age (n = 11). d Frequency of SA-β-gal(+) from < 40 (n = 5) and > 40 (n = 6) HSF, and from > 40 OASF (n = 4) and > 40 RASF (n = 4) cultures (*Mann-Whitney). e CDKN1A and LMNB1 mRNA expression in < 40 (n = 3) and > 40 (n = 5) HSF cultures (*Mann-Whitney). f Frequency of SA-β-gal(+) from < 40 (n = 5) and > 40 (n = 6) HSF cultures treated with TNFα, H2O2 or untreated (CT) (*Friedman, ##Mann-Whitney)

To evaluate the influence of oxidative or inflammatory stress on SF senescence we developed a model of stress-induced senescence. To this aim, 14-day cultures of normal SF were briefly exposed to TNFα or H2O2 before the onset of senescence (day 2 for TNFα, day 5 for H2O2) and the presence of SA-β-gal(+) senescent cells was analyzed at the end of the experiment. Both TNFα and H2O2 significantly increased the proportion of senescent SA-β-gal(+) in young SF. Analysis of old SF confirmed an elevated proportion of senescent cells in basal conditions and showed that TNFα and H2O2 induced a more limited increase, only significant upon H2O2 exposure (Fig. 2f).

Collectively, these results show that SF cultures from younger individuals are highly susceptible to stress-induced senescence, whereas SF from older individuals show increased spontaneous senescence in 14-day cultures.

Expression of SASP mediators by senescent SF

Next, we used the model of SF stress-induced senescence as described above to analyze whether SF senescence is also paralleled by increased expression of the pro-inflammatory factors characteristic of the SASP.

We collected RNA and supernatants from control or senescent SF induced by H2O2 or TNFα in 14-day cultures. mRNA expression of the p16-encoding gene, CDKN2A, and CDKN1A confirmed increased SF senescence (Fig. 3a), and mRNA expression of pro-inflammatory SASP-associated factors: IL6 and CXCL8, monocyte recruitment chemokine CCL2 and matrix metallopeptidase protein MMP3 were determined. All these factors were up-regulated by TNFα- and, more variably, by H2O2-induced senescence (Fig. 3b). These findings were mirrored by a similar increase in the levels of secreted IL-6 and IL-8 proteins in culture supernatants, also more consistently with TNFα (Fig. 3c).

Analysis of senescent markers and SASP mediators in stress-induced senescent SF. HSF in 14-day cultures subjected to stress-induced senescence with H2O2 or TNFα. a Change in CDKN2A and CDKN1A mRNA expression (n = 8). b Change in IL6, CXCL8, MMP3 and CCL2 mRNA expression (n = 12). c Change in IL-6 and IL-8 protein levels (n = 8). (*Wilcoxon test)

Since the pro-inflammatory cytokine TNFα is a strong short-term inducer of these factors in SF, we examined the kinetics of cytokine expression upon TNFα treatment to confirm that the observed late up-regulation of inflammatory gene expression is associated to senescence rather than to a persistent transcriptional response to TNFα. Kinetics analysis indicated that expression of IL6 and CXCL8 was comparable between control and TNFα senescent SF after 8 days in culture, started to increase in TNFα-senescent cultures by day 11 in culture and reached the peak expression by day 14, the endpoint of senescent cultures. These findings rule out a direct contribution of the early TNFα challenge to the late SASP expression (see in Additional file 2: Figure S2).

These results indicate that stress-induced senescence enhanced the expression of factors characteristic of the SASP in SF, and that the up-regulation of the inflammatory genes is temporally associated to the acquisition of senescence rather than to persistent transcriptional effects. Under these circumstances, pharmacological targeting of senescent cells can provide a therapeutic opportunity to reduce senescence-associated inflammation. To test this hypothesis, we treated TNFα-induced senescent SF for 72 h with fenofibrate, a PPARα agonist recently been reported to have potent senolytic and senomorphic activity in senescent chondrocytes and tumour cell lines [29, 30]. Fenofibrate treatment of TNFα-senescent SF provoked a reduction of CDKN2A expression to levels comparable of control SF (Fig. 4). Fenofibrate did not induce increased cell death as assessed by microscopy or lactate dehydrogenase (LDH) activity in supernatants, thus pointing to a senomorphic rather that senolytic effect. This reduction in CDKN2A expression was accompanied by a significant decrease in the expression of IL6, CXCL8 and CCL2 but not that of MMP3 (Fig. 4).

Effect of fenofibrate treatment in TNFα-induced senescent SF. 14-day senescent (SEN) and control (CT) SF were treated with fenofibrate (FB, 25 μM) for 72 h. Graphics show the changes in CDKN2A and SASP factors IL6, CXCL8, MMP3 and CCL2 mRNA expression in relation to untreated CT SF (n = 7) (*Wilcoxon test)

To model the potential impact of senescence on the response of SF to the inflammatory environment of arthritic joints, TNFα-induced senescent SF were stimulated with a secondary challenge of TNFα for 24 h. TNFα re-stimulation induced a significant increase in the mRNA expression of the SASP components IL6, CXCL8 and CCL2 in senescent compared to control SF (Fig. 5a). Likewise, secretion of the cytokines IL-6 and IL-8 was enhanced in senescent SF after TNFα treatment (Fig. 5b).

Response to an acute inflammatory damage of TNFα-induced senescent SF. 14-day senescent (SEN) and control (CT) SF were treated with TNFα. Untreated CT was used as reference. a Change in IL6, CXCL8, MMP3 and CCL2 mRNA expression (n = 9). b Change in IL-6 and IL-8 protein levels (n = 6). (*Wilcoxon test)

Collectively, these findings indicate that the response of senescent SF to further inflammatory challenge is heightened, so that senescence potentiates the expression and production of inflammatory mediators.

Discussion

Tissue accumulation of senescent cells has been identified as a deleterious factor that promotes inflammation and tissue damage in different human diseases and animal models of aging related diseases. Regarding joint diseases, evidence of this concept has been only provided in human and experimental OA, with the main focus on chondrocytes and cartilage damage. Human cartilage and chondrocyte cultures from OA patients have shown increased number of senescent cells that contribute to cartilage degradation by increased IL-1, IL-6 and MMP-3 expression [12, 14].

We have studied cell senescence in variably aged normal ST and found an increased proportion of p16(+) cells in aged donors in the absence of inflammatory pathology, and at levels that parallel those observed in similarly aged OA or RA tissues. Furthermore, cultured normal SF exhibit levels of senescence that correlate well with the age of the donors and that are also significantly increased in the > 40 year-old group. Similar observations have previously been described in mouse and human skin fibroblasts, where senescence was associated to defective repair and a pro-inflammatory SASP, but its implications in skin disease have not been studied [31,32,33]. Lung fibrosis fibroblasts also show senescent features and a profibrotic and SASP phenotype that contributes to experimental lung fibrosis [22]. The contribution of senescence of other cell lineages such as macrophages, chondrocytes or cardiomyocytes, to different aging pathologies such as arteriosclerosis, OA or cardiomyopathy has also been demonstrated by senolytic intervention in animal models [15, 34, 35]. Although typical SASP cytokines and other pro-inflammatory factors are commonly represented in different cell types, cell and tissue-specific differences occur that may explain the different pathological consequences of senescence such as defective repair, fibrosis or inflammatory damage [36, 37].

Our observations suggest that synovial senescent SF accumulation occurs progressively along normal aging, from relatively early ages, and preceding the age of peak prevalence of RA. Interestingly, in old OA or RA diseased synovium no further increase was observed in the proportion of p16 senescent cells or in ex vivo cultured senescent SF compared to age-matched normal synovial tissues. Only in RA synovium from young (< 40 years old) individuals, an increased proportion of senescent cells was observed. A potential limitation of our study is that the number of control biopsies was relatively low due to their origin, i. e., healthy donors, but the sample size allowed statistical comparisons that showed significant changes. Another limitation is the limited availability of RA tissues from patients under 40 years-old. Only histological samples but not SF cultures from patients under this age were available.

We have also confirmed the capacity of oxidative stress and TNFα to induce SF senescence ex vivo. Therefore, SF senescence may be a consequence of inflammatory cell damage in younger RA patients but could also be interpreted as premature synovial cell aging preceding and contributing to RA development. The observed senescent SF phenotype includes enhanced expression of typical SASP factors with relevant roles in the pathogenesis of RA such as IL-6, IL-8, MCP-1 and MMP-3, as well as an enhanced response to further TNFα stimulation. In endothelial cells, a similar positive feedback mechanism has been described by which TNFα-mediated senescence activates the secretion of factors that sustain senescence and cytokine production via JAK/STAT pathway activation [38].

To further explore the potential of senolytic intervention to reduce the expression of pro-inflammatory factors in SF, we treated senescent SF cultures with fenofibrate, an agent that we found able to reduce cell senescence in chondrocytes. Fenofibrate reduced the expression of the senescence marker CDKN2A in SF cultures, confirming previous findings in tumour cell lines [29], although the mechanism is still unclear since we did not observe increased death in fenofibrate-treated senescent SF. Such reduction of CDKN2A expression was associated to a reduction of pro-inflammatory factors. Further studies are needed to confirm the relevance of this process in the development and progression of RA and to develop senescence based therapies.

Another process, mechanistically linked to senescence and inflammation, is the activation of a reparative program by reprograming cells with stem pluripotent capacity. This has been explored in animal models by the expression of the NANOG pluripotency marker. Mosteiro et al have elegantly described the link between senescence and reprogramming, and proposed that the senescent cells send signals to neighboring cells to promote reprogramming, with IL-6 being of particular relevance [19]. Multilineage-differentiating NANOG(+) cells have been isolated from human synovial tissues [39, 40].

Interestingly, we observed an increase of NANOG expression in inflammatory OA and RA tissues compared to control ST providing evidence of the link between this factor and the inflammatory process. However, in normal older tissues, in spite of the accumulation of senescent cells, NANOG expression was not increased which suggests that higher inflammatory, i.e. IL-6, levels are required to activate reprogramming and regeneration.

In summary, our data describe the kinetics of senescent SF accumulation in synovial tissue along normal aging and in inflammatory joint disease, and confirm the potential of these cells to contribute to the RA pathology by producing inflammatory mediators.

Conclusions

This study provides evidence showing that senescent cells accumulate in synovial tissues in normal aging and prematurely in RA. We demonstrate that senescent SF show enhanced pro-inflammatory and tissue-damaging mediators that may contribute to the pathogenesis of RA. Therefore, removal of senescent cells or senolytic strategies could be a potential intervention to prevent or reduce synovial inflammation in RA. This adds RA and possibly other chronic arthritides to the group of diseases associated to increased tissue cell senescence where senolytic/senomorphic pharmacological interventions should be further investigated.

Methods

Patients and synovial biopsies

ST were obtained by arthroscopic knee biopsies from patients who fulfilled the American Rheumatism Association revised criteria for RA (n = 43) [41]. All patients had active disease characterized by inflammation of at least one knee joint. OA synovial tissues were obtained by synovectomy at prosthetic join replacement surgery (n = 18) and histologically normal synovial tissues from healthy individuals without joint disease at elective arthroscopy for minor traumatic lesions, excluding those tissues with significant inflammatory cell infiltration (n = 15). All patients signed a written informed consent, and the study was approved by ethics committees of Hospital Clinic, Barcelona, and Hospital 12 de Octubre, Madrid (N° CEI:17/085).

Immunolabelling of synovial tissues

Immunohistochemical staining was performed using a standard indirect avidin-biotin peroxidase method using EnVision System-HRP Labelled Polymer (DAKO, Carpinteria, CA, USA). The following antibodies and matched isotype controls were used: anti-CDKN2A/p16INK4a (EPR1473 IgG clone, Abcam, Cambridge, UK) and anti-NANOG mAb (D73G4 IgG clone, Cell Signaling). Pretreatment included microwave heating for 15 min in Tris EDTA Tween 20 pH 9. One representative section for each synovial tissue was photographed and digitalized using a Zeiss Axiocam ERc5s camera and Zen 2012 software (Zeiss, Jena, Germany) on a Zeiss Axio Scope.A1 microscope and the number of p16 and NANOG positive cells per synovium area (mm2) was quantified.

Double hsp47 (anti-hsp47 mAb M16.10A1 IgG2b clone, Assay Designs, Ann Arbor, MI, USA) or CD68 (anti-CD68 mAb KP1 IgG1 clone, DAKO) and p16 labelling by IF was also performed using sequential incubation with anti-goat IgG Alexa-Fluor 594 (red) and anti-mouse IgG1 Alexa-Fluor 488 (green) secondary antibodies (Invitrogen Molecular Probes, Eugene, OR, USA) respectively.

Sections were counterstained with haematoxylin or 4′,6-diamidino-2-phenylindole (DAPI) as indicated.

SF cultures

SF cultures were established by explant growth of small biopsy fragments in Dulbecco’s modified Eagle’s medium (DMEM) supplemented with 10% heat inactivated fetal bovine serum (FBS) (Lonza, Verviers, Belgium) and used after 3rd passage.

For a model of stress-induced senescence, SF (5000 cells/cm2) were cultured for a total of 14 days and treated with a short course of oxidative stress with H2O2 (200 μM) (Sigma-Aldrich, Madrid, Spain) for 1 h on day 5, or exposure to TNFα (100 ng/ml) (PreproTech, Rocky Hill, NJ, USA) for 72 h on day 2. Medium was changed every other day and, on day 13, it was replaced by 0.5% FBS. RNA and culture supernatants were collected to analyze senescence and SASP mediators. Aditionally, 14-days-cultured SF were treated with fenobribrate (25 μM, 72 h) (Secalip™, Lacer SA, Spain) or TNFα (20 ng/ml, 24 h).

Cell cycle analysis

SF (n = 3) were seeded in a density of 5000 cells/cm2 and grown for 14 days. After trypsinization SF were fixed with cold ethanol 70% and stained with propidium iodide (20 pg/ml) in presence of RNase A (Roche, Brandford, USA) 100 μg/ml at 37 °C for 30 min [42]. Finally, SF were analyzed by flow cytometry on a BD FACSCalibur instrument (Becton Dickinson, San José, CA, USA).

Senescence-associated beta-galactosidase (SA-β-gal) assay

Quantification of senescence SF in cultures was determined by SA-β-gal assay. The assay was performed as described Debacq-Chainiaux et al [25]. Cells nuclei were counterstained with DAPI. Three to five random fields for each condition were photographed and digitalized by a Nikon Eclipse TE 2000-S microscope using the 100x objective. The total number of SF in the cultures was quantified by DAPI(+) nucleus using ImageJ software (http://rsb.info.nih.gov/ij), and percentage of senescent SA-β-gal(+) SF was determined.

Quantitative real time-PCR (qRT-PCR) analyses

Total RNA was extracted using TRI Reagent (Invitrogen) according to the manufacturer’s protocol. For the quantification of mRNA, 1μg was used for first strand cDNA synthesis with High Capacity cDNA Transcription Kit (Applied Biosystems, Foster City, CA, USA).

For PCR amplification we used cDNA and primers added to Power Sybr Green PCR Master Mix (Applied Biosystems). The sequences of PCR primers used are listed in additional table (see Additional file 3: Table S1). β-ACTIN was used as an endogenous reference. qRT-PCRs were performed on an Applied Biosystems 7500 Fast Real-Time PCR System (Applied Biosystems). For relative quantification we compared the amount of target normalized to the endogenous reference using 2-∆∆Ct formula (Ct = threshold cycle).

Enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA)

Measurement of IL-6 and IL-8 in culture supernatants were determined by single specific ELISA (Biolegend Inc., San Diego, CA, USA) according to the manufacturer protocols. The read-out for all ELISAs was carried out with a MultiskanEX plate reader (ThermoScientific).

Statistical analysis

Data were analyzed using GraphPad Prism software v6.0 (GraphPad Software, San Diego, CA, USA). Correlation was analysed by Pearson’s test. Means were compared by one-way ANOVA with Holm-Sidak’s post hoc test, Friedman test with Dunn’s multiple comparisons, Mann-Whitney test or Wilcoxon test as appropriate. A p value < 0.05 was considered statistically significant (*p < 0.05, **p < 0.01, ***p < 0.001).

Availability of data and materials

Data generated or analyzed during this study are included in this published article and its supplementary information files. Data not shown are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

Abbreviations

- DAPI:

-

4′,6-diamidino-2-phenylindole

- DMEM:

-

Dulbecco’s modified Eagle’s medium

- ELISA:

-

Enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay

- FBS:

-

Fetal bovine serum

- IF:

-

Immunofluorescence

- IHC:

-

Immunohistochemistry

- LDH:

-

Lactate dehydrogenase

- OA:

-

Osteoarthritis

- p16:

-

p16INK4a

- qRT-PCR:

-

quantitative real time-PCR

- RA:

-

Rheumatoid arthritis

- SASP:

-

Senescence-associated secretory phenotype

- SF:

-

Synovial fibroblasts

- ST:

-

Synovial tissues

References

Franceschi C, Campisi J. Chronic inflammation (Inflammaging) and its potential contribution to age-associated diseases. J Gerontol A Biol Sci Med Sci. 2014;69:S4–9.

Franceschi C, Bonafè M, Valensin S, Olivieri F, De Luca M, Ottaviani E, et al. Inflamm-aging. An evolutionary perspective on immunosenescence. Ann N Y Acad Sci. 2000;908:244–54.

Frasca D, Blomberg BB. Inflammaging decreases adaptive and innate immune responses in mice and humans. Biogerontology. 2016;17:7–19.

Coppé J-P, Patil CK, Rodier F, Sun Y, Muñoz DP, Goldstein J, et al. Senescence-Associated Secretory Phenotypes Reveal Cell-Nonautonomous Functions of Oncogenic RAS and the p53 Tumor Suppressor. Downward J, editor. PLoS Biol. 2008;6:e301.

Campisi J. Senescent cells, tumor suppression, and organismal aging: good citizens. Bad Neighbors Cell. 2005;120:513–22.

Baker DJ, Wijshake T, Tchkonia T, LeBrasseur NK, Childs BG, van de Sluis B, et al. Clearance of p16Ink4a-positive senescent cells delays ageing-associated disorders. Nature. 2011;479:232–6.

López-Otín C, Blasco MA, Partridge L, Serrano M, Kroemer G. The hallmarks of aging. Cell. 2013;153:1194–217.

Waaijer MEC, Parish WE, Strongitharm BH, van Heemst D, Slagboom PE, de Craen AJM, et al. The number of p16INK4a positive cells in human skin reflects biological age: p16INK4a in human skin reflects biological age. Aging Cell. 2012;11:722–5.

Salama R, Sadaie M, Hoare M, Narita M. Cellular senescence and its effector programs. Genes Dev. 2014;28:99–114.

Baker DJ, Childs BG, Durik M, Wijers ME, Sieben CJ, Zhong J, et al. Naturally occurring p16Ink4a-positive cells shorten healthy lifespan. Nature. 2016;530:184–9.

Xu M, Bradley EW, Weivoda MM, Hwang SM, Pirtskhalava T, Decklever T, et al. Transplanted Senescent Cells Induce an Osteoarthritis-Like Condition in Mice. J Gerontol A Biol Sci Med Sci. 2016;glw154.

Diekman BO, Sessions GA, Collins JA, Knecht AK, Strum SL, Mitin NK, et al. Expression of p16 INK 4a is a biomarker of chondrocyte aging but does not cause osteoarthritis. Aging Cell. 2018;17:e12771.

Greene MA, Loeser RF. Aging-related inflammation in osteoarthritis. Osteoarthr Cartil. 2015;23:1966–71.

Martin JA, Buckwalter JA. Telomere Erosion and senescence in human articular cartilage chondrocytes. J Gerontol A Biol Sci Med Sci. 2001;56:B172–9.

Jeon OH, Kim C, Laberge R-M, Demaria M, Rathod S, Vasserot AP, et al. Local clearance of senescent cells attenuates the development of post-traumatic osteoarthritis and creates a pro-regenerative environment. Nat Med. 2017;23:775–81.

Alarcón GS. Epidemiology of rheumatoid arthritis. Rheum Dis Clin N Am. 1995;21:589–604.

Li Y, Goronzy JJ, Weyand CM. DNA damage, metabolism and aging in pro-inflammatory T cells. Exp Gerontol. 2018;105:118–27.

Goronzy JJ, Matteson EL, Fulbright JW, Warrington KJ, Chang-Miller A, Hunder GG, et al. Prognostic markers of radiographic progression in early rheumatoid arthritis. Arthritis Rheum. 2004;50:43–54.

Mosteiro L, Pantoja C, Alcazar N, Marión RM, Chondronasiou D, Rovira M, et al. Tissue damage and senescence provide critical signals for cellular reprogramming in vivo. Science. 2016;354:aaf4445.

Bartok B, Firestein GS. Fibroblast-like synoviocytes: key effector cells in rheumatoid arthritis. Immunol Rev. 2010;233:233–55.

Laberge R-M, Awad P, Campisi J, Desprez P-Y. Epithelial-Mesenchymal transition induced by senescent fibroblasts. Cancer Microenviron. 2012;5:39–44.

Schafer MJ, White TA, Iijima K, Haak AJ, Ligresti G, Atkinson EJ, et al. Cellular senescence mediates fibrotic pulmonary disease. Nat Commun. 2017;8:14532.

Ressler S, Bartkova J, Niederegger H, Bartek J, Scharffetter-Kochanek K, Jansen-Durr P, et al. p16 INK4A is a robust in vivo biomarker of cellular aging in human skin. Aging Cell. 2006;5:379–89.

Izquierdo E, Cañete JD, Celis R, Del Rey MJ, Usategui A, Marsal S, et al. Synovial fibroblast hyperplasia in rheumatoid arthritis: Clinicopathologic correlations and partial reversal by anti-tumor necrosis factor therapy. Arthritis Rheum. 2011;63:2575–83.

Debacq-Chainiaux F, Erusalimsky JD, Campisi J, Toussaint O. Protocols to detect senescence-associated beta-galactosidase (SA-βgal) activity, a biomarker of senescent cells in culture and in vivo. Nat Protoc. 2009;4:1798–806.

Dimri GP, Lee X, Basile G, Acosta M, Scott G, Roskelley C, et al. A biomarker that identifies senescent human cells in culture and in aging skin in vivo. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1995;92:9363–7.

Hernandez-Segura A, Brandenburg S, Demaria M. Induction and Validation of Cellular Senescence in Primary Human Cells. J Vis Exp [Internet]. 2018 [cited 2019 Jan 22]; Available from: https://www.jove.com/video/57782/induction-and-validation-of-cellular-senescence-in-primary-human-cells

Freund A, Laberge R-M, Demaria M, Campisi J. Lamin B1 loss is a senescence-associated biomarker. Magin TM, editor. Mol Biol Cell. 2012;23:2066–75.

You B-J, Hour M-J, Chen L-Y, Luo S-C, Hsu P-H, Lee H-Z. Fenofibrate induces human hepatoma Hep3B cells apoptosis and necroptosis through inhibition of thioesterase domain of fatty acid synthase. Sci Rep [Internet]. 2019 [cited 2019 Aug 5];9. Available from: http://www.nature.com/articles/s41598-019-39778-y

Nogueira-Recalde U, Lorenzo-Gómez I, Blanco FJ, Loza MI, Grassi D, Shirinsky V, et al. Fibrates as drugs with senolytic and autophagic activity for osteoarthritis therapy. EBioMedicine. 2019;45:588–605.

Demaria M, Desprez PY, Campisi J, Velarde MC. Cell autonomous and non-autonomous effects of senescent cells in the skin. J Invest Dermatol. 2015;135:1722–6.

Waldera Lupa DM, Kalfalah F, Safferling K, Boukamp P, Poschmann G, Volpi E, et al. Characterization of skin aging–associated secreted proteins (SAASP) produced by dermal fibroblasts isolated from intrinsically aged human skin. J Invest Dermatol. 2015;135:1954–68.

Brun C, Jean-Louis F, Oddos T, Bagot M, Bensussan A, Michel L. Phenotypic and functional changes in dermal primary fibroblasts isolated from intrinsically aged human skin. Exp Dermatol. 2016;25:113–9.

Roos CM, Zhang B, Palmer AK, Ogrodnik MB, Pirtskhalava T, Thalji NM, et al. Chronic senolytic treatment alleviates established vasomotor dysfunction in aged or atherosclerotic mice. Aging Cell. 2016;15:973–7.

Anderson R, Lagnado A, Maggiorani D, Walaszczyk A, Dookun E, Chapman J, et al. Length-independent telomere damage drives post-mitotic cardiomyocyte senescence. EMBO J. 2019;38:e100492.

Hudgins AD, Tazearslan C, Tare A, Zhu Y, Huffman D, Suh Y. Age- and Tissue-Specific Expression of Senescence Biomarkers in Mice. Front Genet [Internet]. 2018 [cited 2019 Mar 13];9. Available from: http://journal.frontiersin.org/article/10.3389/fgene.2018.00059/full

Liu J-Y, Souroullas GP, Diekman BO, Krishnamurthy J, Hall BM, Sorrentino JA, et al. Cells exhibiting strong p16 INK4a promoter activation in vivo display features of senescence. Proc Natl Acad Sci. 2019;116:2603–11.

Kandhaya-Pillai R, Miro-Mur F, Alijotas-Reig J, Tchkonia T, Kirkland JL, Schwartz S. TNFα-senescence initiates a STAT-dependent positive feedback loop, leading to a sustained interferon signature, DNA damage, and cytokine secretion. Aging. 2017;9:2411–35.

Arufe MC, De la Fuente A, Fuentes I, de Toro FJ, Blanco FJ. Chondrogenic potential of subpopulations of cells expressing mesenchymal stem cell markers derived from human synovial membranes. J Cell Biochem. 2010;111:834–45.

Toyoda E, Sato M, Takahashi T, Maehara M, Nakamura Y, Mitani G, et al. Multilineage-differentiating stress-enduring (muse)-like cells exist in synovial tissue. Regen Ther. 2019;10:17–26.

Arnett FC, Edworthy SM, Bloch DA, McShane DJ, Fries JF, Cooper NS, et al. The American rheumatism association 1987 revised criteria for the classification of rheumatoid arthritis. Arthritis Rheum. 1988;31:315–24.

Chen N, Guo D, Guo Y, Sun Y, Bi H, Ma X. Paclitaxel inhibits cell proliferation and collagen lattice contraction via TGF-β signaling pathway in human tenon’s fibroblasts in vitro. Eur J Pharmacol. 2016;777:33–40.

Acknowledgements

We are grateful to the Servicio de Traumatología y Cirugía Ortopédica (Hospital 12 de Octubre, Madrid, Spain) for synovial biopsies and to Vanessa Miranda for technical assistance.

Funding

This work was supported by the Fondo de Investigación Sanitaria, Instituto de Salud Carlos III (FIS 16/00032, RETICS RD16/0012 RIER) cofinanced by European Regional Development Fund (FEDER).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

MJD, AV, GC and JLP conceived and designed the experiments. MJD, AV, AU, SE, EM and CM performed the research, collected and analyzed data. JDC, FJB and JLP provided samples. MJD, AV, GC and JLP interpreted data and wrote the paper. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

All patients signed a written informed consent, and the study was approved by ethics committees of Hospital Clinic, Barcelona, and Hospital 12 de Octubre, Madrid (N° CEI:17/085).

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing financial interests. A.V. is currently working as editor at Springer Healthcare Iberica SL, Madrid, Spain and declares competing non-financial interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary information

Additional file 1: Figure S1.

Double hsp47/p16 and CD68/p16 labelling of synovial tissues. Representative images of synovial tissues labelled for hsp47 and CD68 (red), p16 (green) and merge. Arrows indicate senescent double positive cells for each label.

Additional file 2: Figure S2.

Kinetics of IL6 and CXCL8 mRNA expression in senescent SF. SF were culture for 14 days and subjected to TNFα-induced senescence. Graphics show IL6 and CXCL8 mRNA levels in senescent (SEN) and control (CT) SF at the indicated time-points (n = 2).

Additional file 3: Table S1.

Primer sequences used for quantitative real-time PCR analysis.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made. The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver (http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/) applies to the data made available in this article, unless otherwise stated.

About this article

Cite this article

Del Rey, M.J., Valín, Á., Usategui, A. et al. Senescent synovial fibroblasts accumulate prematurely in rheumatoid arthritis tissues and display an enhanced inflammatory phenotype. Immun Ageing 16, 29 (2019). https://doi.org/10.1186/s12979-019-0169-4

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s12979-019-0169-4