Abstract

Background

Lack of respectful maternity care (RMC) is increasingly recognized as a human rights issue and a key deterrent to women seeking facility-based deliveries. Ensuring facility-based RMC is essential for improving maternal and neonatal health, especially in sub-Saharan African countries where mortality and non-skilled delivery care remain high.

Few studies have attempted to quantitatively identify patient and delivery factors associated with RMC, and none has modeled the influence of provider characteristics on RMC. This study aims to help fill these gaps through collection and analysis of interviews linked between clients and providers, allowing for description of both patient and provider characteristics and their association with receipt of RMC.

Methods

We conducted cross-sectional surveys across 61 facilities in Kigoma Region, Tanzania, from April to July 2016. Measures of RMC were developed using 21-items in a Principal Components Analysis (PCA). We conducted multilevel, mixed effects generalized linear regression analyses on matched data from 249 providers and 935 post-delivery clients. The outcomes of interest included three dimensions of RMC—Friendliness/Comfort/Attention; Information/Consent; and Non-abuse/Kindness—developed from the first three components of PCA. Significance level was set at p < 0.05.

Results

Significant client-level determinants for perceived Friendliness/Comfort/Attention RMC included age (30–39 versus 15–19 years: Coefficient [Coef] 0.63; 40–49 versus 15–19 years: Coef 0.79) and self-reported complications (reported complications versus did not: Coef − 0.41). Significant provider-level determinants included perception of fair pay (Perceives fair pay versus unfair pay: Coef 0.46), cadre (Nurses/midwives versus Clinicians: Coef − 0.46), and number of deliveries in the last month (11–20 versus < 11 deliveries: Coef − 0.35).

Significant client-level determinants for Information/Consent RMC included labor companionship (Companion versus none: Coef 0.37) and religiosity (Attends services at least weekly versus less often: Coef − 0.31). Significant provider-level determinants included perception of fair pay (Perceives fair pay versus unfair: Coef 0.37), weekly work hours (Coef 0.01), and age (30–39 versus 20–29 years: Coef − 0.34; 40–49 versus 20–29 years: Coef − 0.58).

Significant provider-level determinants for Non-abuse/Kindness RMC included the predictors of age (age 50+ versus 20–29 years: Coef 0.34) and access to electronic mentoring (Access to two mentoring types versus none: Coef 0.37).

Conclusions

These findings illustrate the value of including both client and provider information in the analysis of RMC. Strategies that address provider-level determinants of RMC (such as equitable pay, work environment, access to mentoring platforms) may improve RMC and subsequently address uptake of facility delivery.

Similar content being viewed by others

Explore related subjects

Find the latest articles, discoveries, and news in related topics.Plain English summary

Lack of respectful maternity care (RMC) discourages women from seeking facility-based deliveries. RMC is essential for improving maternal and newborn health in sub-Saharan African countries where rates of maternal deaths and non-skilled delivery care are high. We conducted surveys in 61 facilities in Kigoma Region, Tanzania from April to July 2016. Principal components analysis was used to identify three dimensions of RMC. Multilevel regression analyses were conducted on matched data from 249 providers and 935 post-delivery clients. Our outcomes of interest included three dimensions of RMC: 1) Friendliness, Comfort, and Attention, 2) Information and Consent, and 3) Non-abuse and Kindness. Client age, self-reported delivery complications, provider perception of fair pay, cadre, and number of deliveries attended were important factors for receipt of RMC related to Friendliness, Comfort, and Attention. Having a birth companion, client religiosity, provider perception of fair pay, and provider age were important factors for receipt of RMC related to Information/Consent. Provider age and access to electronic mentoring were important factors for receipt of RMC related to Non-abusive/Kindness. Strategies that promote equitable pay, give providers short-term respite away from maternity care, and increase access to mentoring opportunities may improve RMC and uptake of facility delivery.

Background

Worldwide maternal deaths remain common, with approximately 830 women dying each day from known and largely preventable causes [1]. Access to and use of skilled birth attendance is key to prevention of maternal mortality [2]. Approximately 75–80% [3,4,5,6,7] of maternal deaths worldwide result from obstetric complications and are preventable given access to appropriate interventions. Maternal mortality remains a particularly formidable challenge in Tanzania, where the maternal mortality ratio (556 maternal deaths per 100,000 live births) has demonstrated no detectable reduction over the past 10 years [8]. The percentage of women delivering at a health facility (63%) remains low despite ongoing efforts to increase facility-based delivery [8].

Lack of respectful maternity care (RMC), which includes disrespect and abuse (D&A), has been increasingly recognized [9,10,11,12,13,14] and demonstrably identified as a key deterrent for women seeking facility-based deliveries [2, 9, 10, 15,16,17,18,19,20,21,22,23,24,25,26,27,28]. Lack of RMC decreases patient satisfaction with services and mediates lack of access to skilled maternity care by reducing the likelihood that patients will return to skilled care for future deliveries [13, 26,27,28], and by building distrust of facility-based delivery at the community level [29, 30]. Furthermore, lack of RMC may reduce access to appropriate intervention even among patients already within a facility for delivery care by reducing patient-provider communication [31].

The presence of provider-client interpersonal barriers is increasingly suspected to interfere with attempts to increase skilled birth attendance. Bowser and Hill’s review describes seven manifestations of D&A which constitute the current typology in the D&A literature: physical abuse, non-consented care, non-dignified care (including verbal abuse), discrimination, abandonment, and detainment in facilities [11]. Such behaviors are widely recognized to violate patients’ basic human rights. The White Ribbon Alliance (WRA) completed a review of international and multinational human rights instruments related to maternal health rights and the domains of D&A. The resulting Respectful Maternity Care Charter defined seven rights of childbearing women [32] (Table 1): Freedom from harm and ill treatment; Right to information, informed consent and refusal, and respect for choices and preferences, including the right to companionship of choice whenever possible; Confidentiality, privacy; Dignity, respect; Equality, freedom from discrimination, equitable care; Right to timely health care and to the highest attainable level of health; and Liberty, autonomy, self-determination, and freedom from coercion.

Worldwide, an alarmingly high prevalence of women have reported mistreatment according to these typologies of D&A, with reports ranging from 20 to 78% [12, 13, 22, 31, 33]. Understanding facilitators of and barriers to RMC is critical to the design of interventions to promote RMC in these contexts.

Qualitative studies have identified several potential patient factors associated with lack of RMC. These include the following: race/ethnicity and religion, depending upon context [34,35,36,37]; age, with unmarried adolescents [38, 39] and older women of high parity [40, 41] thought to be at particular risk; socioeconomic status (SES), with poor women at perceived higher risk of D&A [42,43,44,45]; and medical conditions, with women with HIV thought to face multiple forms of discrimination [35, 46, 47].

While qualitative studies have identified factors associated with RMC, few studies have quantitatively examined the associations between individual patient characteristics and report of D&A. In Tanzania, women who had attended secondary education or greater, primiparous women, those with experience of low mood in the past year, and those with a personal history of physical abuse or rape were more likely to report experiences of D&A during their delivery; married women were less likely to report D&A [33]. In a follow-up community survey, poor women, women who reported low mood at the time of exit interview, and more educated women were again more likely to report D&A during their delivery, whereas grand multiparas (given birth five or more times) and women with Cesarean sections were less likely to report D&A. Abuya et al., in their exploration of specific forms of D&A during childbirth in Kenya, demonstrated that older women were less likely than younger women to experience non-confidential care, that women of higher parity were more likely to be detained for lack of payment and more likely to have bribes demanded, that married women were less likely to be detained but more likely to be neglected, and that women without a companion were less likely to experience demands for bribes or detention [13].

To our knowledge, published research to date has not modeled relationships between health care provider demographic or practice characteristics and provision of RMC. Qualitative studies, however, including in-depth interviews with providers of maternity care, have generated several hypotheses. Provider training itself is thought to create “distancing” and separation between providers and patients, potentially generating insensitivity toward women in childbirth [39, 48] through lack of attention to patient-provider dynamics, or even through direct rationalization of D&A [49]. Poor provider pay is thought to contribute to lack of RMC provision [17, 50, 51], as is lack of encouragement by facility leadership [17]. Provider demoralization and “moral distress” due to weak health systems, limited supplies, and understaffing have also been well described in relationship to lacking RMC [10, 17, 26, 49].

To date, there is no standardized or widely agreed upon way to define or measure either RMC or D&A. Scales for measurement of RMC have recently been proposed in Ethiopia [52] and in the USA and Canada [53], however, the tools are not yet validated in other contexts. Few studies have attempted to quantitatively identify patient and delivery factors associated with RMC. No identified studies have matched patient and provider interviews or any other form of modeling inclusive of linked patient and provider experience.

This novel study utilizes interviews linked between clients and providers from hospitals, health centers, and dispensaries to describe receipt and delivery of RMC, allowing for description of both patient and provider characteristics and their association with receipt of RMC. This study also contributes to the science around RMC by constructing measures of RMC based on domains from the WRA RMC Charter.

Methods

Study design and setting

We conducted cross-sectional surveys consisting of facility-based client exit interviews and provider interviews across 61 facilities (6 hospitals, 25 health centers, and 30 dispensaries) in Kigoma Region, Tanzania from April 30 to July 1, 2016.

Kigoma Region covers 45,066 km2 and is located in the northwest corner of Tanzania, bordering Lake Tanganyika, the Democratic Republic of Congo, and Burundi. Kigoma Region’s population in 2012 was 2,127,930 with an annual growth rate of 2.4% and 370,374 households [54]. Approximately 83% of the population live in rural areas where farming is the primary economic activity [54]. Nine out of 10 adults in Kigoma Region have attained a primary school education [54]. Less than two-thirds of births (62.8%) in Kigoma region occur in a health facility [55].

During our study, the Ministry of Health, Community Development, Gender, the Elderly and Children (MoHCDGEC) was implementing a number of efforts to improve maternal health in Tanzania. These efforts included the National Roadmap Strategic Plan to Accelerate Reduction of Maternal, Newborn and Child Deaths in Tanzania 2008–2015, the Big Results Now (BRN) initiative, and Wazazi Nipendeni (“Parents Love Me”; a safe motherhood multimedia campaign). Additionally, since 2006, the Project to Reduce Maternal Deaths in Tanzania has worked in Kigoma Region with the aim of decreasing maternal mortality.

Sampling and data collection

Facility sampling

All hospitals (n = 6) and non-refugee camp health centers (n = 25) in Kigoma Region were included in the study. A sample of 30 dispensaries (of the approximately 163 dispensaries conducting deliveries in the region) was selected using the following criteria: 1) had an estimated 180 or more births per year; 2) had two or more onsite health providers; 3) was a site for BRN or project partner facility improvements, 4) referred patients to one of the 25 health centers; and 5) to maximize geographic distribution.

Provider sampling

The sampling frame for the provider survey comprised a list of all health care providers in the selected facilities. Providers were recruited if they were available during the study period and routinely provided labor and delivery care services. Providers were categorized into three cadres: 1) clinicians [Assistant Medical Officers/Clinical Officers/Assistant Clinical Officers], nurses/midwives [Nurse Officers/Assistant Nurse Officers/Registered Nurses/Midwives/Enrolled Nurses], other staff [Medical Attendants/Maternal and Child Health Aides]). Medical Doctors and specialists were excluded from participation due to the small number in the region. A sample of 189 provider interviews was needed to detect a 5% relative mean change in key variables of interest with 90% power and an alpha of 0.05.

Client sampling

Convenience sampling was used to enroll women as they exited delivery care services. Clients were eligible if they were 15 to 49 years of age and received delivery care services at the facility. Due to the focus of the project on routine labor and delivery care, clients were excluded if they delivered at home or on the way to the facility, had a cesarean section delivery, or experienced a stillbirth or neonatal death. A sample of 908 client interviews was needed to detect a 15% absolute difference in the variables of interest 90% power and an alpha of 0.05 (assuming a 50% reference proportion).

Interview procedures and study tools

Interview guides were developed in English and translated into Swahili. Questionnaires were pre-tested in January 2016. Final questionnaires were translated from English to Swahili and back-translated to English. Informed consent was obtained from each respondent and confirmed with the respondent’s thumbprint. All client and provider interviews were administered face-to-face by an interviewer in Swahili. Interviews were conducted at the facility on the day of discharge, most commonly on the same day of delivery or the following day. The Client Post-Delivery Exit Interview Questionnaire captured sociodemographic characteristics, perceptions of and satisfaction with services, and pregnancy history and intention. The Provider Interview Questionnaire and Self-administered Knowledge Test were designed to capture information about provider demographic characteristics, education and training, supervision and mentorship, clinical knowledge, perceptions of the work environment, and current labor and delivery practices.

Development of respectful maternity care measure

An initial 29 items were taken from the survey data to develop the RMC measure; these items were chosen based on domains from the WRA Respectful Maternity Care Charter and previously published research on RMC [11,12,13,14, 19,20,21, 33, 40]. The RMC items are described in detail in Table 1. Items representing disrespect (rather than respect) were reverse coded prior to inclusion. In initial scale reliability testing, no items were found to be redundant or negatively associated with the scale. Four items with low item-to-scale correlations were dropped (Discharge time, Facility supplies, Facility cleanliness, and Wait time). The remaining 25-item measure displayed strong internal consistency with Cronbach’s alpha of 0.83 and an inter-item correlation of 0.17. In support of criterion validity, Spearman testing found that the RMC measure was positively associated with the variable Client satisfaction with care (rho = 23.8, p-value < 0.001).

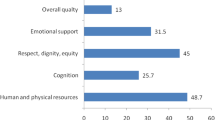

The 25 items were then entered into a Principal Components Analysis (PCA) to establish dimensionality of the scale with the aim of retaining the maximum amount of variance possible. The mean Kaiser-Meyer-Olkin measure of sampling adequacy was 0.81 and all individual item measures were greater than 0.68, indicating strong relationships among scale items [56]. Visualization of the scree plot supported a three-component solution for RMC (Fig. 1); client RMC scores were calculated for each of the first three components.

Items that loaded highest on the first principal component included Advise on comfort measures, Friendliness, Visit regularly, and Pay close attention. This first component was therefore termed the RMC Dimension 1 (RMC-D1), defined by the domains of Friendliness, Comfort, and Attention. Items that loaded highest on the second principal component included Consent before procedures/exams, Explain what will happen, Explain procedures/exams beforehand, and Post-delivery counseling index. This second component was therefore termed RMC Dimension 2 (RMC-D2), defined by the domains of Information and Consent. Items that loaded highest on the third principal component included Absence of physical abuse, Absence of emotional abuse, Encouragement, and Kindness. This component was therefore termed RMC Dimension 3 (RMC-D3), defined by Non-abuse and Kindness.

Outcome variables

The outcome variables of interest included the continuous variables RMC-D1 score, RMC-D2 score, and RMC-D3 score to represent receipt of three dimensions of RMC.

Independent variables

Client-level

The client-level variables of interest included:

-

Client age: 15 to 19, 20 to 29, 30 to 39, 40 to 49 years of age, age unknown by client;

-

Literacy: Able to read and write, Unable to both read and write;

-

Highest education attended: No education, primary, secondary, college or university;

-

Total live births: Two or fewer, three or more;

-

Marital status: Not in union, in union;

-

Frequency of attendance at religious services: Less than once a week, once a week or more often;

-

Companion in labor: No, yes;

-

Companion at time of delivery: No, yes;

-

Self-reported delivery complicationsFootnote 1: No, yes; and

-

SESFootnote 2: Low, low middle, middle, high middle, high wealth.

Provider-level

The provider-level variables of interest included:

-

Provider age: 20 to 29, 30 to 39, 40 to 49, 50 years or older;

-

Sex: Male, female;

-

Highest education completed: Primary, secondary, college or university;

-

Cadre: Clinicians, nurses/midwives, other staff;

-

Years in cadre: Continuous;

-

Years at the facility: Continuous;

-

Work hours per week: Continuous;

-

Number of deliveries attended in last month: One to 10, 11 to 20, 21 to 30, 31 or more, Don’t know;

-

Has on-site supervisor: No, yes;

-

Job satisfaction: Very satisfied, a little satisfied, neither satisfied nor dissatisfied, a little dissatisfied, very dissatisfied;

-

Perception paid fairly for job duties: No, yes;

-

Perception of adequacy of training for job duties: No, yes;

-

Perception in-service training has helped job performance: No, yes;

-

Access to Electronic mentoring opportunities: Access to zero, one, two, or three opportunities related to e-learning, emergency call system, and teleconference;

-

Recent complications summative index: Has dealt with zero, one, two, three, or four types of complications in the last month related to hemorrhage, eclampsia, obstructed labor, and puerperal sepsis;

-

Delivery ever-training summative indexFootnote 3: Pre- or in-service delivery training in 25 items, continuous;

-

Delivery pre-service summative index3: Pre-service delivery training in 25 items, continuous;

-

Delivery in-service summative index3: In-service delivery training in 25 items, continuous;

-

Recent delivery practice summative index3: Provision of delivery services in 25 items in the last 3 months, continuous; and

-

Clinical knowledge test score: Percent correct on 64 knowledge questions on the topics of antenatal care, routine delivery, newborn, complications, partograph, and postpartum.

Analytic approach

Client and provider data were matched by asking providers on duty at the time of the delivery and by asking clients which provider most commonly provided their care; only matched client and provider interviews were included in the analysis. Data analyses were conducted using Stata 14.1. Bivariate analyses were conducted to identify client and provider variables associated with the outcome variables of interest; variables with a significant unadjusted relationship (p < 0.10) with the dependent variables were included in multivariate modeling. Multilevel, mixed-effects generalized linear models were fitted for the first three RMC PCA scores (RMC-D1 score, RMC-D2 score, and RMC-D3 score) to identify variables with a significant adjusted relationship (p < 0.05). Clustering of data by facility was further accounted for through inclusion of a facility identification cluster variable.

Results

From April 30–July 1, 2016, a total of 960 delivery clients and 361 providers (Clinicians n = 72, Nurses/midwives n = 188, Other staff n = 98) were interviewed. Following exclusion of data from non-matched clients and providers, data from 935 delivery clients and 249 providers (Clinicians n = 69, Nurses/midwives n = 176, Other staff n = 85) were used in the analysis.

Descriptive characteristics

Half of clients were 20 to 29 years of age (50.3%) and received care at a health center (50.6%). The majority of clients included in the study were married (91.0%), attended at least weekly religious services (86.4%), and have attended primary school education (67.3%). Nearly 45% of clients reported having a birth companion with them during labor (44.7%), while only 12% reported having a birth companion with them at the time of delivery. About 13% of clients reported that they experienced delivery complications (12.9%). (Table 2).

With respect to characteristics of RMC, nearly all clients reported that they were greeted respectfully upon admission (96.3%), while less than half reported that the provider introduced themselves (45.6%). Two-thirds of clients reported the provider explained what to expect in labor (63.0%). Regarding procedures and exams, most clients reported that the provider asked for consent (80.4%), explained the procedures and exams ahead of time (70.7%), and gave them the results (87.5%). One-third of clients reported the provider encouraged them to have a companion (32.7%). About three-quarters of clients reported feeling comfortable asking the provider questions (75.4%) and reported believing the information they gave to the provider would remain confidential (77.2%). Nearly all clients reported receiving privacy during exams and counseling (94.2%), although a few reported that other clients could overhear their conversations with the provider (7.9%). On average, clients received 6.7 out of 12 post-delivery counseling elements (Tables 1 and 3).

Most clients reported that the provider was friendly (94.3%), and about three-quarters of clients reported the provider was very kind (76.0%) and very encouraging (79.4%). Nearly nine of 10 clients reported the provider advised them about comfort measures (88.7%); however, receipt of comfort measures from the provider was low at an average of less than two out of six comfort measures (1.3). Clients overwhelmingly reported the provider paid close attention to them during labor (93.5%) and came when they called for them (97.7%). Physical and emotional abuse was reported infrequently by clients at 1.3% and 2.7%, respectively. (Table 3).

Four in 10 providers were 20 to 29 years of age (41.0%), while one-fifth of providers were 50 years or older (21.7%). The majority of providers included in the study were female (64.7%), college/university educated (66.7%), and in the nurse/midwife cadre (61.0%). On average, providers reported working about 10.3 years in their cadre and 7.5 years at their facility, and reported working an average of 54.8 work hours per week. Two-thirds of providers (63.9%) reported conducting from one to 10 deliveries in the last month. Providers reported receiving in-service training on an average of 8 training elements; almost 9 of 10 providers reported in-service training has helped their job performance. Nearly half of providers reported not having access to electronic mentoring opportunities (48.2%). Less than half of providers stated they were satisfied with their job (44.6%), and less than one-fifth of providers feel they are paid fairly for their job duties (18.5%). On average, providers correctly answered 55.1% of the clinical knowledge questions. (Table 4).

Receipt of respectful maternity care dimension 1 (RMC-D1): Friendliness, Comfort, and Attention

Results of bivariate analyses for RMC-D1 – Friendliness, Comfort, and Attention, are displayed in Appendix. Based on bivariate analyses for RMC-D1, the following variables were included in the multivariable model: Client age, Total live births, and Self-reported delivery complications; Provider cadre, Ever-training summative index score, Delivery pre-service summative index score, Recent delivery practice summative index score, Number of deliveries attended in last month, Recent complications summative index score, Access to electronic mentoring opportunities, Perception paid fairly for job duties, and Perception in-service training has helped job performance.

In multi-level, multivariate regression analyses, clients aged 30 to 39 years and clients aged 40 to 49 years had significantly higher RMC-D1 scores compared to clients 15 to 19 years (Coefficient [Coef] 0.63, 95% Confidence Intervals [CI] 0.14–1.13; Coef 0.79, 95% CI 0.18–1.39, respectively). Clients who reported that they experienced delivery complications had significantly lower RMC-D1 scores compared to clients who did not report complications (Coef -0.41, 95% CI -0.72-[-0.10]). The client variable of Total live births was not found to have a significant adjusted association with RMC-D1 score. (Table 5).

Clients of providers who perceived that they were paid fairly for their job duties had significantly higher RMC-D1 scores compared to clients of providers who perceived they are not paid fairly (Coef 0.46, 95% CI 0.04–0.88). Clients of Nurses/midwives had significantly lower RMC-D1 scores compared to clients of clinicians (Coef -0.46, 95% CI -089-[-0.03]). Clients of providers who reported attending 11 to 20 deliveries in the last month had significantly lower RMC-D1 scores compared to clients of providers who attended 1 to 10 deliveries (Coef -0.35, 95% CI -0.67-[-0.02]). Provider variables not found to have a significant adjusted association with RMC-D1 score included the following: Delivery ever-training summative index, Delivery pre-service summative index, Recent delivery practice summative index, Recent complications summative index, Access to electronic mentoring opportunities, and Perception in-service training has helped job performance. (Table 5).

The intraclass correlation (ICC) defines the proportion of the total variance that can be attributed to the hierarchal grouping by the provider variable. Net of all independent variables included in the final RMC-D1 model, 18% of the total variance (ICC = 0.18) is explained by the provider level.

Receipt of respectful maternity care dimension 2 (RMC-D2): Information and Consent

Results of bivariate analyses for RMC-D2 – Information and Consent, are displayed in Appendix. Based on bivariate analyses for RMC-D2, the following variables were included in the multivariable model: Client age, Highest education attended, Total live births, SES, Frequency of attendance at religious services, Companion in labor, Companion at time of delivery; Provider age, Number of deliveries attended in last month, Access to electronic mentoring opportunities, Perception paid fairly for job duties, and Work hours per week.

In multi-level, multivariate regression analyses, clients who had a birth companion in labor had significantly higher RMC-D2 scores compared to clients who did not have a companion in labor (Coef 0.37, 95% CI 0.06–0.68). Clients who reported attending religious services at least weekly had significantly lower RMC-D2 scores compared to clients who reported less than weekly attendance (Coef -0.31, 95% CI -0.06-[-0.02]). Client-level variables found not to have a significant adjusted relationship with RMC-D2 score included Age, Highest education attended, Wealth quintile, Total live births, and Companion at time of delivery. (Table 5).

Clients of providers who perceived they were paid fairly for their job duties had significantly higher RMC-D2 scores compared to clients of providers who perceived they are not paid fairly (Coef 0.37, 95% CI 0.06–0.68). Clients of providers who reported working more hours per week had significantly higher RMC-D2 scores compared to clients of providers who work fewer hours (Coef 0.01, 95% CI 0.00–0.02). Clients of providers aged 30 to 39 and 40 to 49 years had significantly lower RMC-D2 scores compared to clients of providers aged 20 to 29 years (Coef -0.34, 95% CI -0.63-[-0.05]; Coef -0.58, 95% CI -0.86-[-0.29]). Provider variables not found to have a significant adjusted association with RMC-D2 score included Number of deliveries attended in last month and Access to electronic mentoring opportunities. Net of all independent variables included in the final RMC-D2 model, nearly one-quarter of the total variance (ICC = 0.24) is explained by the provider level. (Table 5).

Receipt of respectful maternity care dimension 3 (RMC-D3): Non-abuse and Kindness

Results of bivariate analyses for RMC-D3 – Non-abuse and Kindness, are displayed in Appendix. Based on bivariate analyses for RMC-D3, the following variables were included in the multivariable model: Client age, Marital status, Companion in labor, Self-reported delivery complications; Provider age, Cadre, Delivery ever-training summative index score, Delivery in-service summative index score, Number of deliveries attended in the last month, and Access to electronic mentoring opportunities.

In multi-level, multivariate regression analyses, none of the client variables were found to have a significant adjusted association with RMC-D3 score. Clients of providers who were aged 50 years or more had significantly higher RMC-D3 scores compared to clients of providers in the 20 to 29 year age group (Coef 0.34, 95% CI 0.09–0.58). Clients of providers who reported access to two types of electronic mentoring had significantly higher RMC-D3 scores compared to clients of providers with no access to electronic mentoring opportunities (Coef 0.37, 95% CI 0.07–0.65). The provider variables of Age, Cadre, Delivery ever-training summative index score, Delivery in-service summative index score, and Number of deliveries attended in the last month were not found to have a significant adjusted association with RMC-D3 score. Net of all independent variables included in the final RMC-D3 model, only 3% of the total variance (ICC = 0.03) is explained by the provider level. (Table 5).

Discussion

As maternal mortality and unskilled birth attendance continue to be high in sub-Saharan Africa, it is essential that the factors that influence health-seeking behavior and their determinants are better understood. In our study, we sought to identify the client and provider factors that predict receipt of three dimensions of RMC among delivery clients in Kigoma, Tanzania. The results provide insights into how dimensions of RMC, including receipt of friendly, comfort, and attention (RMC-D1), information and consent (RMC-D2), and non-abuse and kindness (RMC-D3) during labor and delivery are differentially influenced by characteristics of clients and their providers.

Client factors were significantly associated with the first two dimensions of RMC relating to friendliness, comfort, and attention (RMC-D1), and information and consent (RMC-D2). In our analyses, client age mattered; clients in their 30’s and 40’s perceived receiving significantly higher levels of RMC related to friendliness, comfort, and attention compared to clients in their teens. It is possible that health care providers interact and treat teens differently simply because they are younger than the providers are themselves, or it is possible that the providers perceive teens as too young to become a mother. Multiple qualitative studies and reviews thereof have pointed to younger women, particularly adolescents, as potential targets of discrimination and potential recipients of less respectful care [10, 11, 14]. Our findings are consistent with the analysis presented by Abuya et al. of D&A during childbirth in Kenya, where younger patients were significantly more likely to receive non-confidential care than older patients [13]. Our findings are in contrast to those by Kruk et al., however, who did not find age associated with receipt D&A in Tanzania [33].

Whether or not the client reported to have had delivery complications also influenced the first dimension of RCM; clients who reported delivery complications had a lower RMC score related to friendliness, comfort, and attention compared to those without perceived complications. There are two potential explanations for this finding: 1) the stress that providers experience during complications and emergencies may make them more likely to exhibit disrespectful behavior; or 2) the experience of complications lowers the client’s overall perception of the delivery experience.

Companionship in labor was found to be a positive factor for receipt of RMC related to information and consent; clients with a companion in labor received a higher level of RMC-D2. This finding is not surprising as providers may feel more accountable for providing better information and counseling when someone in addition to the client is present; a companion may also help increase the client’s understanding of information. Interestingly, more frequent attendance at religious services was a significant determinant of receipt of a lower level of RMC related to information and consent. It is possible that more religious women may interpret or receive these components differently than their less religious counterparts; alternatively, providers may display a particular bias against giving information to these women. Collectively, these findings provide a better understanding of how client characteristics—or provider perceptions and biases related to those characteristics—may influence provision of respectful care.

Provider factors were also significantly associated with the first two dimensions of RMC, and were the only factors of significance for the third non-abuse and kindness dimension of RMC. Nurses/midwives as compared to clinicians, and providers who attended 11 to 20 deliveries in the last month as compared to providers who attended fewer deliveries, were found to provide lower levels of RMC related to friendliness, comfort, and attention. These findings suggest that the high workload of labor and delivery care—commonly found among nurses/midwives—may lead to less positive interpersonal interactions with clients. Nurse/midwifes may experience prolonged contact with labor and delivery clients, as opposed to the often intermittent contact that clinicians experience, which may reduce a provider’s ability to give friendly, comforting, and attentive care day after day. Evidence bolstering this hypothesis comes from psychology research on the depleting effect of decision fatigue on subsequent self-control and active initiative [57]: providers may know that treating clients with respect is important and necessary, but may grow increasingly less able to provide respectful care with the demands of ongoing urgent clinical decision making without respite.

While job satisfaction was not found to be correlated with RMC, providers who perceived they were paid fairly for their work duties as compared to those who did not feel this way provided significantly better RMC related to friendliness, comfort, and attention, and RMC related to information and consent. These findings suggest that the perception of pay equity (versus pay inequity) positively influences interpersonal interactions and care provision, and likely reflects an underlying attitude that providers feel appreciated and motivated to do their work. Numerous qualitative studies and reviews thereof have highlighted health worker descriptions of low salaries as a particular stressful aspect of negative work environments resulting in unprofessional behavior [10, 35, 45, 58]. In Tanzania specifically, inadequate compensation for long hours, ineligibility for overtime pay, and lost opportunities to pursue other income-generating activities have been described as contributing to health care providers great dissatisfaction with their working environments [17].

Providers who reported working more as compared with fewer hours per week provided significantly higher levels of RMC related to information and consent. This finding may seem contradictory to the previously discussed finding that nurses/midwives and providers who conduct a higher number of deliveries provide less friendly, comforting, and attentive care. We contend, however, that friendliness/comfort/attention is a dissimilar construct from information sharing and consent, and therefore, it is not surprising to see disparate patterns of association. It is possible that providers who work more hours take more time to give information during labor and delivery care due to having more work hours, or they may have more opportunity from which to gain expertise communicating with and counseling clients through more frequent experience. Providers in their 30’s and 40’s provided lower levels of RMC related to information and consent, compared to providers in their 20’s. This finding suggests a possible shift in pre-service education whereby client counseling and consent have been emphasized in the education of more recent graduates or perhaps that younger providers simply have more motivation for sharing their knowledge with clients.

With respect to RMC related to non-abuse and kindness, the findings suggest that provider characteristics of age and access to electronic mentoring are protective. Providers aged 50 years and older provided higher levels of RMC care related to non-abuse and kindness than providers in their twenties. A potential explanation for this finding is that older providers, who are more experienced in labor and delivery, may be more patient and therefore less likely to respond negatively. Providers who reported access to two types of electronic mentoring, such as an emergency call line, teleconference, or e-learning, gave significantly better RMC related to non-abuse and kindness compared to clients of providers with no access to electronic mentoring opportunities. It is possible that providers with greater access are more likely to have received RMC training or that access to these types of mentorship opportunities improves provider’s underlying attitude toward work and the care of clients.

Strengths and limitations

One strength of our study is the novel way in which we conceptualized and measured RMC. To-date, much of the research and literature around RMC has focused on D&A; we chose to focus on receipt of respectful care as our outcome of interest using the WRA RMC Charter as a conceptual framework. Using PCA to develop our outcomes allowed the identification of three dimensions of RMC in order to identify differences in determinants of RMC by broad dimension. In prior work, disrespect/respect has been operationalized in ways that limit interpretation and implications of findings. First, disrespect has been operationalized as a dichotomous variable where clients having experienced any one or more of a range of disrespectful practices are coded as a “1” [33]. Results from such an analysis are difficult to interpret because there is no differentiation in degree of disrespect; clients reporting not being greeted respectfully are considered to be equivalent in their experience of RMC with those who reported physical and emotional abuse by providers. Second, respect/disrespect has also been operationalized by running separate regression models for each item of respect/disrespect [13]. This approach results in generation of a large amount of data which may or may not be similar across models, making interpretation of findings and development of recommendations challenging.

A second strength of this study is the use of matched client and provider data. This was a particularly essential strategy given our findings that a larger number provider factors significantly influenced RMC compared to client factors. Identifying provider determinants of RMC allows for the development of recommendations aimed at specific provider characteristics (e.g., new graduates, cadre) or perceptions (e.g., age bias, religious bias) that would not be known otherwise. Another strength of this work is that we operationalized select independent variables in new ways. For example, provider-level Delivery ever-training index, Delivery pre-service index, and Recent delivery practice index variables were operationalized by summing multiple delivery care elements; these variables allowed the analyses to differentiate the importance of both dose and timing of training and practice to provision of RMC.

It is critical to understand the limitations of our work. First, the study was cross-sectional with non-random sampling, eliminating our ability to make causal inferences and generalize findings. Previously collected household-level Reproductive Health Survey (RHS) data in Kigoma from 2016 and a planned 2018 RHS in Kigoma provides a timely opportunity to analyze representative RMC data. Second, our questionnaire did not have items that fit into Article V and Article VII of the WRA RMC Charter, limiting our ability to account for certain known risk factors for receipt of non-respectful care. History of self-reported depression and history of past abuse or rape have both been associated with higher rates of abuse in health care settings in both high-resource [59, 60] and low-resource contexts [33]. Third, while using PCA as a means to create outcome variables has its strengths, it also has its limitations. Interpretation of coefficients is constrained; while we can easily interpret the direction and significance level of relationships, it is more problematic to understand to what extent a change in an independent variable has a meaningful change in receipt of RMC. Additionally, PCA rarely matches conceptual frameworks perfectly, especially for complex constructs such as RMC. Though strong patterns emerged in our PCA, not every item clustered with the most logical component (e.g., Inform about findings of exam/procedures loaded highest on the first component, not the second component, as expected).

The site of client interviews at facilities poses an additional important limitation, likely generating an underestimation of true prevalence of D&A and an overestimation of receipt of RMC. Two independent studies of D&A treatment during facility delivery in Tanzania have demonstrated markedly lower reports of D&A from interviewed clients when interviewed at the site of the facility, with significant increases in reporting upon follow up in the community [31, 33]. Another limitation of our data is that some women, particularly those who delivered in hospitals and health centers, may have had more than one care provider. We attempted to control for this issue by matching women with the provider who they reported spending the greatest amount of time with them. Due to budget and time constraints, our questionnaire items used in the development of RMC measures were not developed on the basis of formative work in Kigoma Region. Rather, these items were a compilation of commonly used RMC elements in prior research. Qualitative work ahead of this study may have uncovered local conceptualizations of RMC that would have been important to include in our measure. Finally, the provider-level variables only accounted for 3% of the variance of RMC-D3, and client variables did not have a significant adjusted relationship with this outcome; this suggests that the RMC-D3 model had a poor overall fit. It is important for future work to attempt to explore client and provider characteristics not considered in this study and potential reframing of the non-abuse and kindness dimension.

Programmatic, policy, and research implications

These findings highlight potential areas of focus for programmatic and policy work, as well as future directions to move the RMC research agenda forward. Given our results that Nurses/midwives and providers who conduct a higher number of deliveries provide lower levels of RMC, improving the work environment for labor and delivery providers may improve delivery care. Strategies that aim to reduce workplace stress—including reduction of moral distress and decision fatigue—and improve providers’ perceptions of workplace support, self-efficacy in providing quality care, and underlying attitude toward work, may contribute to improved interpersonal interactions between clients and providers. Such approaches might include offering high frequency rotational schedules to give labor and delivery providers short-term respite away from providing maternity care. Strategies that increase access to mentoring and peer-to-peer learning opportunities (with fair access across cadres) may improve workplace support, self-efficacy, and enhance feelings of being a respected and valued member of the team. Pre-service and in-service training on RMC, as well as close mentorship following training, is essential to determine the influence of training on knowledge transfer and behavior change. Additionally, ensuring providers receive equitable pay, on-time, every time may increase provider’s sense of worth and underlying attitude towards work.

To move the RMC scientific agenda forward, additional research using matched patient and provider data may improve understanding of the relative importance of patient and provider determinants of RMC. In addition, studies embedded in conceptual models of RMC are needed that aim to standardize and validate measures of RMC. Measures that can be validated across cultural and geographic settings would be particularly valuable so that RMC data can be compared and synthesized across studies. Future analyses would be strengthened through the addition of interaction terms to illuminate the complexities of patient and provider relationships and how these influence respectful care. Given our hypothesis that moral distress and decision fatigue contribute to lack of RMC, future analyses would greatly benefit from inclusion of measures for these constructs. Furthermore, future research may benefit from over-sampling of clinician providers in order to increase the power to detect differences between clinicians and other cadres, and potential differences by gender that were not detected here. Finally, women in low-resource settings may have relatively low expectations of maternity care compared to women in middle- or high-resource settings. Measuring expectations of care and the influence of cultural and gender norms in future research would help advance our understanding of women’s experience of RMC and how expectations and context influence measurement and comparison of RMC across settings.

Conclusion

Despite disrespectful maternity care being increasingly recognized as a key deterrent to women seeking facility-based deliveries, there is less consensus about the comparative importance of patient and provider determinants for RMC. Our findings demonstrate that patient and provider factors differentially influence three dimensions of RMC. Future research is needed that aims to standardize RMC measurement through the lens of a conceptual model of RMC and rooted in a human rights perspective. Strategies that promote more equitable pay, offer rotational schedules with short-term respite away from providing maternity care, and increased access to mentoring and peer-to-peer learning platforms may improve RMC and uptake of facility delivery in low-resource settings. An enhanced understanding of the relationships between patient and provider characteristics may improve the provision of quality labor and delivery services and should be considered in the design of maternity care programs, policies, and future research.

Notes

Women were asked if they had any complications during labor and delivery. The most common self-reported complications included postpartum hemorrhage, prolonged labor, retained placenta, malpresentation, and lacerations.

The variable for SES was developed using principal components analysis (PCA); household assets and characteristics were weighted based on their contribution to the first principal component and summed to create an index score representing five levels of relative household wealth [61].

Providers were asked, “Have you received pre-service training in […]?”; “Have you received in-service training in […]?”; and “Have you conducted […] in the last 3 months?” for the following 25 items: 1) Focused antenatal care; 2) Routine labor and delivery care; 3) Use the partograph; 4) Active management of the third stage of labor; 5) Manual removal of the placenta; 6) Beginning intravenous fluids; 7) Checking for anemia; 8) Administering intramuscular or intravenous magnesium sulfate for the treatment of server pre-eclampsia or eclampsia; 9) Administering intravenous antibiotics; 10) Administering misoprostol or other uterotonic; 11) Bimanual uterine compression (external); 12) Bimanual uterine compression (internal); 13) Suturing an episiotomy; 14) Suturing vaginal lacerations; 15) Suturing cervical lacerations; 16) Vacuum extractor; 17) Forceps; 18) C-section; 19) A blood transfusion; 20) Adult resuscitation; 21) Resuscitating a newborn with bag and mask; 22) Basic Emergency Obstetric and Neonatal Care (BEmONC); 23) Advanced Emergency Obstetric and Neonatal Care; 24) Administering antiretrovirals (ART) for Prevention of Mother-to-Child Transmission (PMTCT); and 25) Rapid diagnostic testing for HIV. Responses were summed to create four indices.

Abbreviations

- BRN:

-

Big results now

- CDC:

-

Centers for disease control and prevention

- CI:

-

Confidence intervals

- Coef:

-

Coefficient

- D&A:

-

Disrespect and abuse

- ICC:

-

Intraclass correlation

- MOHCDGEC:

-

Ministry of health, community development, gender, the elderly, and children

- NBS:

-

National bureau of statistics

- PCA:

-

Principal components analysis

- RHS:

-

Reproductive health survey

- RMC:

-

Respectful maternity care

- RMC-D1:

-

Respectful maternity care-dimension 1

- RMC-D2:

-

Respectful maternity care-dimension 2

- RMC-D3:

-

Respectful maternity care-dimension 3

- SD:

-

Standard deviation

- SE:

-

Standard error

- USAID:

-

United States agency for international development

- WHO:

-

World Health Organization

- WRA:

-

White ribbon alliance

References

WHO, UNICEF, UNFPA, The World Bank and United Nations Population Division. Trends in maternal mortality: 1990 to 2015. Generva; 2015. Access at: http://apps.who.int/iris/bitstream/10665/194254/1/9789241565141_eng.pdf?ua=1.

Adegoke AA, van den Broek N. Skilled birth attendance—lessons learnt. BJOG. 2009;116(Suppl 1):33–40.

Harvey SA, Ayabacab P, Bucaguc M, Djibrinad S, Edsona WN, Gbangbadee S, et al. Skill birth attendant competence: an initial assessment in four countries, and implications for the safe motherhood movement. Int J Gynecol Obstet. 2004;87:203–10.

Koblinksy MACO, Heichelheim J. Organizing delivery care: what works for safe motherhood? Bull World Health Organ. 1999;77:399–404.

Ronsmans C, Graham WJ. Maternal mortality: who, when, where, and why. Lancet. 2006;368(9542):1189–200.

World Health Organization. Beyond the numbers: reviewing maternal deaths and complications to make pregnancy safer. Geneva: Department of Reproductive Health and Research, World Health Organization; 2004.

De Brouwere V, Tonglet R, Van Lerberghe W. Strategies for reducing maternal mortality in developing countries: what can we learn from the history of the industrialized west? Tropical Med Int Health. 1998;3:771–82.

Ministry of Health, Community Development, Gender, Elderly and Children (MoHCDGEC) [Tanzania Mainland], Ministry of Health (MoH) [Zanzibar], National Bureau of Statistics (NBS), Office of the Chief Government Statistician (OCGS), and ICF. Tanzania demographic and health survey and malaria indicator survey (TDHS-MIS) 2015–16. Dar es Salaam: MoHCDGEC, MoH, NBS, OCGS, and ICF; 2016.

Kujawski S, Mbaruku G, Freedman LP, Ramsey K, Moyo W, Kruk ME. Association between disrespect and abuse during childbirth and women’s confidence in health facilities in Tanzania. Matern Child Health J. 2015;19(10):2243–50.

Bohren M, Vogel JP, Hunter EC, Lutsiv O, Makh SK, Souza JP, Aguiar C, Saraiva CF, Diniz AL, Tuncalp O, Javadi D, Oladapo OT, Khosla R, Hindin MJ, Gulmezoglu AM. The mistreatment of women during childbirth in health facilities globally: a mixed-methods systematic review. PLoS Med. 2015;12(6):e10001847.

Bowser D, Hill K. Exploring evidence for disrespect and abuse in facility based childbirth: a report of a landscape analysis. USAID-TRAction Project, Harvard School of Public Health and University Research Co., 2010. Access at: https://cdn2.sph.harvard.edu/wp-content/uploads/sites/32/2014/05/Exploring-Evidence-RMC_Bowser_rep_2010.pdf.

Asefa A, Bekele D. Status of respectful and non-abusive care during facility-based childbirth in a hospital and health centers in Addis Ababa. Ethiop Reprod Health. 2015;12:33.

Abuya T, Warren CE, Miller N, Njuki R, Ndwiga C, et al. Exploring the prevalence of disrespect and abuse during childbirth in Kenya. PLoS One. 2015;10(4):e0123606.

Warren CE, Njue R, Ndwiga C, Abuya T. Manifestations and drivers of mistreatment of women during childbirth in Kenya: implications for measurement and developing interventions. BMC Preg Childbirth. 2017;17:102.

Gabrysch S, Campbell OM. Still too far to walk: literature review of the determinants of delivery service use. BMC Preg Childbirth. 2009;9:34.

Gebrehiwot T, Coicolea I, Edin K, San SM. Making pragmatic choices: women’s experiences of delivery care in northern Ethiopia. BMC Preg Childbirth. 2012;12:1113.

Mselle LET, Moland KM, Mvungi A, Evjen-Olsen B, Kohi TW. Why give birth in a health facility? Users’ and providers’ accounts of poor quality of birth care in Tanzania. BMC Health Ser Res. 2013;13:174.

Kruk ME, Paczkowsi M, Mbaruku G, de Pinho H, Galea S. Women’s preferences for place of delivery in rural Tanzania: a population-based discrete choice experiment. Am J Public Health. 2009;99(9):1666–72.

Bohren MA, Ec H, Munthe-Kaas HM, Souza JP, Vogel JP, Gulmezoglu AM. Facilitators and barriers to facility-based delivery in low- and middle-income countries: a qualitative evidence synthesis. Reprod Health. 2014;11(1):71.

Shiferaw S, Spigt M, Godefrooij M, Melkamu Y, Tekie M. Why do women prefer home births in Ethiopia? BMC Preg Childbirth. 2013;13:5.

Rosen HE, Lynam PF, Carr C, Reis V, Ricca J, Bazant ES, Bartlett LA. Direct observation of respectful maternity care in five countries: a cross-sectional study of health facilities in east and southern Africa. BMC Preg Childbirth. 2015;15:306.

Okafor II, Ugwu EO, Obi SN. Disrespect and abuse during facility-based childbirth in a low-income country. Int J Gynaecol Abstet. 2015;128(2):110–3.

Misago C, Kendall C, Freitas P, Haneda K, Silveira D, Onuki D, Mori T, Sadamori T, Umenai T. From ‘culture of dehumanization of childbirth’ to ‘childbirth as a transformative expereince’: changes in five municipalities in north-East Brazil. Int J Gynaecol Obstet. 2001;75(Suppl 1):S67–72.

Lukasse M, Laanpere M, Karro H, Kristjansdottir H, Schrolla AM, Van Parys AS, Wangel AM, Schei B. Bidens study, group, pregnancy intendedness and the association with physical, sexual and emotional abuse – a European mulit-country cross-sectional study. BMC Pregnancy Childbirth. 2015;15:120.

Silal S, Penn-Kekana L, Barnighausen T, Schneider H, Harris B, Birth S, McIntyre D. Exploring inequalities in access to and use of maternal health services in South Africa. BMC Health Serv Res. 2012;12:120.

Ishola F, Owolabi O, Filippi V. Disrespect and abuse of women during childbirth in Nigeria: a systematic review. PLoS One. 12(3):e0174084.

D’Ambruoso L, Abbey M, Hussein J. Please understand when I cry out in pain: women’s accounts of maternity services during labor and delivery in Ghana. BMC Public Health. 2005;5:140.

Avorti GS, Beke A, Abekah NG. Predictors of satisfaction with child birth services in public hospitals in Ghana. Int J Health Care Qual Assur. 2011;24(3):223–37.

Freedman LRK, Abuy T, Bellows B, Ndwiga C, Warren CE, Kujawski S, Moyo W, Kruk ME, Mbaruku G. Defining disrespect and abuse of women in childbirth: a research, policy and rights agenda. Bull World Health Organ. 2014;92(12):915–7.

FCI. Care-seeking during pregnancy, delivery and the postpartum period: a study in Homa Bay and Migori districts, Kenya; FCI 2005. New York: The Skill Care Initiative Technical Brief: Compassionate Maternity Care: Provider Communication and Counselling Skills; 2005.

Sando D, Ratcliffe H, McDonald K, Spiegelman D, Lyatuu G, Mwanyika-Sando M, Emil F, Wegner MN, Chalamilla G, Langer A. The prevalence of disrespect and abuse during facility-based childbirth in urban Tanzania. BMC Preg Childbirth. 2016;16:236.

White Ribbon Alliance. Respectful maternity care: the universal rights of childbearing women. Washington, D.C.: 2011. Access at: http://www.healthpolicyproject.com/pubs/46_FinalRespectfulCareCharter.pdf.

Kruk ME, Kujawski S, Mbaruku G, Ramsey K, Moyo W, Freedman LP. Disrespectful and abusive treatment during facility delivery in Tanzania: a facility and community survey. Health Policy Plan. 2014:1–8.

Janevic T, Sripad P, Bradly E, Dimitrievska V. “There’s no kind of respect here” a qualitative study of racism and access to maternal health care among Romani women in the Balkans. Int J Equity Health. 2011;10:53.

Human Rights Watch. “Stop making excuses”: accountability for maternal health care in South Africa. New York: Human Rights Watch; 2011.

Hulton LA, Matthews Z, Stones RW. Applying a framework for assessing the quality of maternal health services in urban India. Soc Sci Med. 2007;64:2083–95.

Jomeen J, Redshaw M. Black and minority ethnic women’s experiences of contemporary maternity care in England. J Reprod Infant Psychol. 2011;29:e9.

Atuyambe L, Mirembe F, Johansson A, Kirumira EK, Faxelid E. Experiences of pregnant adolescents—voices from Wakiso district, Uganda. Afr Health Sci. 2005;5:304–9.

Jewkes R, Abrahams N, Mvo Z. Why do nurses abuse patients? Reflections from south African obstetric services. Soc Sci Med. 1998;47:1781–95.

McMahon SA, George AS, Chebet JJ, Mosha IH, Mpembeni RN, Winch PJ. Experiences of and responses to disrespectful maternity care and abuse during childbirth; a qualitative study with women and men in Morogoro region, Tanzania. BMC Preg Childbirth. 2014;14:268.

Ng’anjo PS, Fylkesnes K, Ruano AL, Moland KM. ‘Born before arrival’: user and provider perspectives on health facility childbirths in Kapiri Mposhi district, Zamiba. BMC Preg Childbirth. 2014;14:323.

Moyer CA, Adongo PB, Aborigo RA, Hodgson A, Engmann CM. ‘They treat you like you are not a human being’: maltreatment during labour and delivery in rural northern Ghana. Midwifery. 2014;30:262–8.

Ith P, Dawson A, Homer CSE. Women’s perspective of maternity care in Cambodia. Women Birth. 2013;26:71–5.

Oyerinde K, Harding Y, Amara P, Garbrah-Aidoo N, Kanu R, Oulare M. A qualitative evaluation of the choice of traditional birth attendants for maternity care in 2008 Sierra Leone: implications for universal skilled attendance at delivery. Maternal Child Health. 2013;17:862–8.

Rahmani Z, Brekke M. Antenatal and obstetric care in Afghanistan—a qualitative study among health care receivers and health care providers. BMC Health Ser Res. 2013;13:166.

Turan JM, Miller S, Bukusi EA, Sande J, Cohen CR. HIV/AIDS and maternity care in Kenya: how fears of stigma and discrimination affect uptake and provision of labor and delivery services. AIDS Care. 2008;20:938–45.

Sando D, Kendall T, Lyatuu G, Ratcliffe H, McDonald K, Mwanyika-Sando M, et al. Disrespect and abuse during childbirth in Tanzania: are women living with HIV more vulnerable? JAIDS. 2014;67(Suppl 4):S228–34.

Uzochukwu BS, Onwujekwe OE, Akpala CO. Community satisfaction with the quality of maternal and child health services in southest Nigeria. East Afr Med J. 2004;81(6):293–9.

Rominski SD, Lori J, Nakua E, Dzomeku V, Moyer CA. When the baby remains there for a long time, it is going to die so you have to hit her small for the baby to come out: justification of disrespectful and abusive care during childbirth among midwifery students in Ghana. Health Policy Plan. 2017;32:215–24.

Onah HE, Ikeako LC, Iloabachie GC. Factors associated with the use of maternity services in Enugu, southeastern Nigeria. Soc Sci Med. 2006;63(7):1870–8.

Knight HE, Self A, Kennedy SH. Why are women dying when they reach hospital on time? A systematic review of the ‘third delay’. PLoS One. 2013;8(5):e63846.

Sherefaw ED, Mengesha TZ, Wase SB. Development of a tool to measure women’s perception of respectful maternity care in public health facilities. BMC Preg Childbirth. 2016;16:67.

Vedam S, Stoll K, Rubashkin N, Martin K, Miller-Vedam Z, Hayes-Klein H, Jolicoeur G, the CCinBC Steering Committee. The mothers on respect (MOR) index: measuring quality, safety, and human rights in childbirth. SSM Population Health. 2017;3:201–10.

National Bureau of Statistics & Office of Chief Government Statistician. The United Republic of Tanzania, Kigoma region: basic demographic and socio-economic profile: Population and Housing Census; 2012. p. 2016. http://www.nbs.go.tz/nbs/takwimu/census2012/2012_CENSUSVol3DATAsheet.pdf.

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Kigoma reproductive health survey: Kigoma region, Tanzania. Atlanta: Centers for Disease Control and Prevention; 2016. p. 2017.

MacCallum RC, Widaman KF, Zhang S, Hong S. Sample size in factor analysis. Psychol Methods. 1999;4(1):84–99.

Vohs KD, Baumeister RF, Schmeichel BJ, Twenge JM, Nelson NM, Tice DM. Making choices impairs subsequent self-control: a limited-resource account of decision making, self-regulation, and active initiative. J Pers Soc Pschycol. 2008;94(5):883–98.

Ganle J, Parker M, Fitzpatrick R, Otupiri E. A qualitative study of health system barriers to accessibility and utilization of maternal and newborn healthcare services in Ghana after user-fee abolition. BMC Pregnancy Childbirth. 2014;14:425.

Swahnberg K, Wijma B, Wingren G, Hilden M, Schei B. Women’s perceived experiences of abuse in the health care system: their relationship to childhood abuse. BJOG. 2004;111:1429–36.

Swahnberg K, Schei B, Hilden M, Halmesmäki E, Sidenius K, Steingrimsdottir T, Wijma B. Patients’ experiences of abuse in health care: a Nordic study on prevalence and associated factors in gynecological patients. Acta Obstet Gynecol Scand. 2007;86:349–56.

Filmer D, Pritchett LH. Estimating wealth effects without expenditure data—or tears: an application to educational enrollments in states of India. Demography. 2001;38(1):115–32.

Acknowledgements

We are grateful to the postpartum women and health providers who gave of their time to participate in the survey. The authors would also like to acknowledge the support of our in-country partner, AMCA Inter Consult, and CDC colleagues Erin Bernstein, Susanna Binzen, Fernando Carlosama, Jonetta Mpofu, Alicia Ruiz, Michelle Schmitz, and intern from Emory University Rollins School of Public Health, Hannah Nguyen.

Funding

This study was funded by Bloomberg Philanthropies and the Fondation H & B Agerup.

Availability of data and materials

All data supporting the findings of this study are contained within the manuscript.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

MD was responsible for the study design, undertook the fieldwork and data collection, analysis, and helped interpret findings and write the manuscript. ET was responsible for the literature search and helped interpret findings and write the manuscript. LK participated in data analysis and helped interpret findings and write the manuscript. AAM helped with data collection and interpret findings. FS helped with the study design, interpret findings, and write the manuscript. GM, SAD, PC, and NM helped interpret findings. All authors read and approved the final manuscript submitted for publication.

The findings and conclusions in this report are those of the authors and do not necessarily represent the official position of the US Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

This project was approved by the National Institute for Medical Research (NIMR) in Tanzania as one activity among a larger set of activities for the Project to Reduce Maternal Deaths in Tanzania. It was also reviewed in accordance with CDC human subjects protection policy and was determined to be non-research. Verbal consent was obtained from all respondents prior to participation. Providers and postpartum women completed the interviews voluntarily.

Consent for publication

Not applicable

Competing interests

All authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Appendix

Appendix

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made. The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver (http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/) applies to the data made available in this article, unless otherwise stated.

About this article

Cite this article

Dynes, M.M., Twentyman, E., Kelly, L. et al. Patient and provider determinants for receipt of three dimensions of respectful maternity care in Kigoma Region, Tanzania-April-July, 2016. Reprod Health 15, 41 (2018). https://doi.org/10.1186/s12978-018-0486-7

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s12978-018-0486-7