Abstract

There is increasing evidence showing that the dynamic changes in the gut microbiota can alter brain physiology and behavior. Cognition was originally thought to be regulated only by the central nervous system. However, it is now becoming clear that many non-nervous system factors, including the gut-resident bacteria of the gastrointestinal tract, regulate and influence cognitive dysfunction as well as the process of neurodegeneration and cerebrovascular diseases. Extrinsic and intrinsic factors including dietary habits can regulate the composition of the microbiota. Microbes release metabolites and microbiota-derived molecules to further trigger host-derived cytokines and inflammation in the central nervous system, which contribute greatly to the pathogenesis of host brain disorders such as pain, depression, anxiety, autism, Alzheimer’s diseases, Parkinson’s disease, and stroke. Change of blood–brain barrier permeability, brain vascular physiology, and brain structure are among the most critical causes of the development of downstream neurological dysfunction. In this review, we will discuss the following parts:

-

Overview of technical approaches used in gut microbiome studies

-

Microbiota and immunity

-

Gut microbiota and metabolites

-

Microbiota-induced blood–brain barrier dysfunction

-

Neuropsychiatric diseases

-

■ Stress and depression

-

■ Pain and migraine

-

■ Autism spectrum disorders

-

-

Neurodegenerative diseases

-

■ Parkinson’s disease

-

■ Alzheimer’s disease

-

■ Amyotrophic lateral sclerosis

-

■ Multiple sclerosis

-

-

Cerebrovascular disease

-

■ Atherosclerosis

-

■ Stroke

-

■ Arteriovenous malformation

-

-

Conclusions and perspectives

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Since Rober Koch first developed a bacterial culture technique in the laboratory [1], Theodour Escherich identified the common gut bacillus Escherichia coli [2], and Élie Metchnikoff found an association between longevity and microbes from dairy food [3], an increasing number of commensal and pathogenic bacteria have been discovered and characterized as exerting a profound influence on human health and behaviors through food digestion, fermentation, metabolism, and vitamin production.

In the past five years, gut microbiota research has become a research“hot spot,” and more than 25,000 gut microbiota-related articles have been published (as of 1st Sep 2019). Using next-generation sequencing (NGS) approaches, large-scale studies such as the Human Microbiome Project (HMP) and the Metagenomics of the Human Intestinal Tract (MetaHIT) project have provided essential references regarding the microbiota composition in human bodies [4, 5]. Biomarkers in the gut are related to a variety of diseases, including metabolic disorders [6, 7], inflammatory bowel diseases (IBD) [8, 9], a variety of cancers [10], and even disorders of the central neural system.

Researchers have identified alterations in the composition of the gut microbiota related to several symptoms or diseases, such as pain, cognitive dysfunction, autism [11, 12], neurodegenerative disorders, and cerebral vascular diseases [13]. The microbiota of different habitats contribute to bidirectional brain-gut signaling through humoral, neural, and immunological pathogenic pathways [14]. The central nervous system (CNS) alters the intestinal microenvironment by regulating gut motility and secretion as well as mucosal immunity via the neuronal-glial-epithelial axis and visceral nerves [15,16,17,18,19]. Extrinsic factors, including dietary habit, lifestyle, infection, and early microbiota exposure, as well as intrinsic factors such as genetic background, metabolite, immunity, and hormone, regulate the composition of gut microflora. On the other hand, bacteria react to these changes by producing neurotransmitters or neuromodulators in the intestine to impact the host CNS. These modulators include bacteria-derived choline, tryptophan, short-chain fatty acids (SCFAs), and intestinally released hormones such as ghrelin or leptin (Fig. 1).

Herein, we will review the progress in gut-brain axis studies and explain how changes in the gut microbiota alter cognitive function, cerebrovascular physiology, and the development of neurological and neuropsychiatric diseases.

Technical approaches in gut microbiome studies

Current technologies do not allow the cultivation of all bacteria isolated from the gut. Two widely adopted culture-free approaches have been devised to effectively quantify and characterize the microbiome, i.e., targeted sequencing and metagenomic sequencing. Targeted sequencing is also referred to as marker gene sequencing [20] including 16S ribosomal RNA (rRNA), internal transcribed spacer (ITS), and 18S rRNA sequencing. In 1977, Woese et al. inferred phylogenetic relationships between prokaryotic organisms using the rRNA small subunit (SSU) genes; this approach was later proven to also work well in eukaryotes [21, 22]. Wilson and Blitchington showed a good agreement of the diversity and 16S rRNA sequences between quantitative cultured cells and direct PCR-amplified bacteria from a human fecal specimen [23].

Researchers now can use this powerful tool to sequence 16S rRNA for assessing microbial taxonomy and diversity from various human specimens.

However, 16S rRNA sequencing achieves only ~ 80% accuracy in the genus level and is not able to fully resolve taxonomic profiles at the species level or strain level, especially with short read lengths [24, 25]. Shotgun sequencing was then developed for the comprehensive profiling of the DNA from microbiota. In 1998, Handelsman et al. first coined the term “metagenome” when cloning DNA fragments from soil-derived biosamples into bacterial artificial chromosomal vectors [26]. In 2002, using the shotgun sequencing approach, Breitbart et al. sequenced a viral metagenome that did not carry rDNAs, and more than 65% of the species that they identified had not been reported previously [27]. The same year witnessed the isolation of the antibiotics Turbomycin A and B from a metagenomic library of soil microbial DNA by Gillespie et al. using a restriction enzyme approach [28]. In 2004, Tyson et al. sequenced biofilms using random shotgun sequencing and determined single-nucleotide polymorphisms at the strain level. It is now understood that the metagenome represents a collection of DNA from the environment, and shotgun sequencing has been widely adopted for metagenomic sequencing [29].

Other technologies including metatranscriptomics [30, 31], metaproteomics [32], and metabolomics [33, 34], can be applied to investigate RNAs, proteins, and metabolites in metagenome-wide association studies (MWAS). The MWAS approach has shown great potential not only in the identification of the microbiome taxonomy but also in the annotation of functions, pathways, and metabolism.

Gut microbiome and host immunity

The human microbiota interacts with the host gut immune system for mutual adaptation and immune homeostasis by tolerating commensal antigens [35]. The perturbation of gut microbiota could lead to a higher incidence of autoimmunity and allergy [36]. Both innate immunity and adaptive immunity in the human gastrointestinal tract play critical roles as guardians that maintain pathogen-host homeostasis. In terms of innate immunity, pathogen-associated molecular patterns (PAMPs) were first suggested to describe the pathogenic targets recognized by pattern recognition receptors (PRRs) from the host innate immune system [37, 38]. PAMPs represent “molecular signatures” of a pathogen class, such as the highly conserved microbial structures consisting of lipopolysaccharides (LPS), lipoteichoic acid (LTA), CpG, or dsRNAs. Gut microbes and their derivatives constantly interact with PRRs in intestinal epithelial cells, immune cells in peripheral blood, and even cells in the CNS. Microbiota dysbiosis has been reported to trigger gut barrier dysfunctions, such as changes in tight junctions, mucous layers, and secretion of immunoglobulin A and intraepithelial lymphocytes [39, 40]. In the rodent model, hippocampal neurogenesis is proved to be controlled by the stimulation of toll-like receptors (TLRs). TLR2 is responsible for neurogenesis, while TLR4 exhibits a contrary function [41, 42]. By LPS binding, TLR4 inhibits retinal neurogenesis and differentiation via MyD88-dependent and NF-κB signaling pathways [43]. TLR2 activation also inhibits the proliferation of embryonic neural progenitor cells [44]. The downstream inflammatory cytokine TNF-α further reduces neurogenesis and induces the proliferation of astrocytes [45]. There is also evidence that TLR4 is related to the development of learning and memory [46, 47].

On the other hand, adaptive immunity routinely plays a crucial role in both anti-infection functions and the maintenance of microbiota-host homeostasis to prevent overreaction to harmless antigens. This balance is mainly accomplished by mutual regulation between regulatory T cells and TH17 intestinal lamina propria [48]. Regulatory T cells (Tregs) are crucial in the maintenance of immune homeostasis. The protective immunosuppression signals are delivered through GATA3, Foxp3, and IL-33 expression in regulatory T cells. SCFAs from dietary fiber are produced by Clostridia species, in particular, contributing to the activation and expansion of CD4+Foxp3+ Treg cells [49, 50]. The polysaccharide endocytosed by dendritic cells could promote expansion and differentiation of naïve T cells into Th1 and regulatory T cell subsets [51]. Gut microbiota-activated TH17 cells, characterized by IL-17A, IL-17F, and IL-22 secretion, are responsible for high-affinity IgA secretion, memory CD4+ T cell differentiation and anti-Staphylococcus aureus function [52,53,54,55]. However, dysbiosis of gut bacteria activates T and B cells and further influences the secretion and class switching of IgA in B cells, the differentiation of TH17 cells, and the further recruitment of dendritic cells, group 3 innate lymphoid cells (ILC3) and granulocytes [48]. When TH17 cells are induced by inflammatory signals such as IL-23 overexpression, these cells are likely to be associated with autoimmune diseases, including uveitis and encephalomyelitis [56,57,58,59]. Brain lesions in the hypothalamus-pituitary-adrenal gland axis (HPA) can alter intestinal immunity. In a mouse stroke model, a significant reduction of T and B cells in Peyer’s patches is observed 24 h after stroke [60]. In turn, impairment of the blood–brain barrier (BBB) following stroke is triggered by microbiota changes and immune dysregulation, further allowing brain infiltration of immune cells to react to CNS tissues [61].

Microbiota altered blood–brain barrier and brain structure

BBB is a semipermeable barrier composed of specialized endothelial cells in the microvasculature [62]. The BBB separates the CNS from the peripheral blood [63]. There are a variety of disorders related to microbial-induced BBB dysfunction, which may cause anxiety, depression, autism spectrum disorders (ASDs), Parkinson’s disease, Alzheimer’s disease, and even schizophrenia [61, 64,65,66]. The exact mechanism whereby the microbiota affects BBB physiology remains unknown. Possible mechanisms include BBB modulation by gut-derived neurotransmitters and bacterial metabolites. Rodent models have shown that a loss of the normal intestinal microbiota results in increased permeability of the BBB, while a pathogen-free gut microbiota restores BBB functionality [67]. Metabolic diseases such as diabetes can result in increased permeability of the BBB and, potentially, further progression to Alzheimer’s disease with amyloid-β peptide deposition [64]. Microbiota dysbiosis has been found to alter the protective functions of the BBB, including regulation of permeability [67] through tight junction expression [68] or further behavioral changes [69].

The microbiota composition is also correlated with brain morphology. A germ-free mouse model demonstrated that the microbiota is required for the normal development of hippocampal and microglial morphology [70]. Structural magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) revealed that the patient’s cortical thickness is negatively correlated with the duration of Crohn’s disease [71]. The posterior regions and middle frontal gyrus have also been found to be reduced in adolescent patients [72]. The relative abundance of Actinobacteria is correlated with better organization of the amygdalar, hypothalamic, and thalamic microstructure according to MRI. The changes in structure are associated with better motor speed, attention, and cognitive test scores [73].

Food and food-derived metabolites

As the second-largest metabolic organ in the human body, the gut harbors approximately 1.5 kg of colonized microbiota and metabolic mass from food [74]. The diet pattern plays an essential role in the composition of gut microflora and affects psychiatric conditions such as depression and anxiety [75, 76]. Diets rich in fruits, whole grains, vegetables, and fish have been proved to be beneficial to brain function such as the lower risk of dementia by reducing gut inflammation and neurodegeneration [77]. By far, several well-known “Mediterranean-like” dietary patterns have shown neuroprotective effects, i.e., Mediterranean diet (MeDi), Dietary Approach to Stop Hypertension (DASH) diet, and Mediterranean-DASH Intervention for Neurodegenerative Delay (MIND) diet [77, 78]. Patients with Alzheimer’s disease (AD) and atherosclerosis benefit from these “Mediterranean-like” diets [79]. On the other hand, diet rich in saturated fatty acids, animal proteins, and sugars have been shown to increase the risk of brain dysfunction. A high-fat diet (HFD), or namely “Western” diet, is normally regarded as detrimental to the brain [80]. Excessive intake of HFD is associated with increases in Firmicutes and Proteobacteria and a decrease in Bacteroidetes [81]. HFD also induces plasma and fecal levels of acetate, triggers the overproduction of insulin and ghrelin, and further promotes overfeeding [82]. Obesogenic effects and inflammation caused by HFD can be reduced by uptake of polyphenols from fruits, accompanied with an increase in A. muciniphila.

The food can quickly alter the microbiota composition in the gut. Changing to a high-fat or high-sugar dietary pattern from a low-fat or plant fiber-rich dietary pattern can shift of the microbiome even within one day [83]. A dog experiment revealed that the proportion of carbohydrate and protein was responsible for the change [84]. The Bacteroides abundance was reported to be associated with animal-derived protein and saturated fats, while Prevotella was associated with carbohydrates and simple sugars [85]. Vegetable-based diets can increase SCFAs, accompanied by elevated Prevotella and some fiber-degrading Firmicutes [86]. When fed with fructose, Bacteroidetes was significantly decreased in the mice model, while Proteobacteria, Firmicutes, and pathogenic Helicobacteraceae were significantly increased [87].

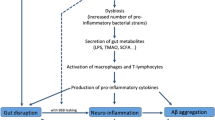

Food patterns and dietary habits result in a change of brain physiology which can be explained by food-derived metabolites (Fig. 2). Metabolites derived from food play important roles in the pathogenesis of brain-related diseases. Recent findings showed the food-derived metabolites include not only SCFAs but also phosphatidylcholine, trimethylamine oxide (TMAO), L-carnitine, glutamate, bile acids, lipids, and vitamins. The food derivatives and microbe-fermented small molecular metabolites are released by gut microbiota into the blood which interacts with the host and further contributes to a variety of disorders, including brain diseases.

The metabolism of phosphatidylcholine which is rich in poultry, egg, and especially red meat, has been reported to involve a crucial biological interaction between the gut microbiota and host [88]. This pathway includes TMAO, a product of the oxidation of trimethylamine (TMA), which is produced during the metabolism of red meat-derived L-carnitine [89]. The levels of TMAO, betaine, and choline have been shown to serve as predictors in the diagnosis and prognosis of cardiovascular diseases [90,91,92]. These gut microbiota-derived metabolites induce and promote foam cell formation via cholesterol accumulation in macrophages. Recent studies have revealed that the Clostridiales, Lachnospiraceae, and Ruminococcus are highly correlated with the area of atherosclerotic lesion and TMAO levels in the plasma. Interestingly, an analog of choline, 3,3-dimethyl-1-butanol (DMB), was shown to inhibit the formation of TMAO in microbes [93]. An increased abundance of Enterobacteriaceae and Ruminococcus is found in atherosclerotic cardiovascular disease patients compared to controls, while butyrate-producing bacteria, including Roseburia and Faecalibacterium, are relatively depleted in these patients [94].

A highly ketogenic diet, with a high-fat, adequate-protein, and low-carbohydrate composition, has been shown to exert an anti-seizure effect [95]. This high-fat, low-carbohydrate pattern is associated with Akkermansia and Parabacteroides and results in a higher seizure threshold by reducing serum gamma-glutamylated amino acid levels and increasing brain GABA/glutamate levels [95]. On the other hand, a high-fat and high-cholesterol diet (HFHC) induces dyslipidemia and triggers the small intestine mucosal immune system, further promoting inflammation and altering the gut microflora [96]. The phylum Firmicutes is positively correlated with carbohydrate oxidation, while Bacteroidetes exhibits a negative correlation. Herbal dietary supplements such as Rhizoma Coptidis alkaloids have been shown to alleviate hyperlipidemia in a mouse model by modulating the gut microflora and bile acid pathways [97].

A high-fiber diet has been reported to improve brain health through multiple effectors [98]. In the mammalian gut, dietary fiber is degraded by bacteria to produce long-chain fatty acids (LCFAs) and SCFAs as metabolites [99]. LCFAs, including lauric acid, promote the differentiation of TH17 cells. The LCFAs are known as trigger factors in the establishment of autoimmune encephalomyelitis model [100]. In contrast, SCFAs usually not only serve as energy sources for epithelial cells but also recruit and expand regulatory T cells and release modulatory cytokines [101]. SCFAs are mainly composed of acetate (40–60%), propionate (20–25%) and butyrate (15–20%) [102, 103]. Acetate and propionate are produced by the Bacteroidetes phylum in particular, while species of the Firmicutes phylum preferentially produce large amounts of butyrate [104]. Systemic loss of SCFAs, especially acetate, is likely to exacerbate inflammatory reactions in germ-free mice, whereas direct acetate drinking is helpful to ameliorate disease by decreasing the level of the inflammatory mediator myeloperoxidase [105]. Propionic acid protects the mouse model from autoimmune colitis better than other SCFAs through the induction of Treg cells [50, 100]. A high-fiber diet inducing butyrate production can protect the brain well and enhance neuron plasticity in a neurogenesis model [98]. It is worth noting that SCFA can manipulate the acetylation and methylation state and further regulating the host’s gene expression and metabolic processes [106]. For example, lower abundances of SCFAs are shown associated with a lower degree of chromatin acetylation [107].

Dietary tryptophan is an essential source of an aryl hydrocarbon receptor (AHR) agonist that limits CNS inflammation by reducing both astrocyte and microglial pathogenic activities and experimental autoimmune encephalomyelitis (EAE) development [108, 109]. Tryptophan is usually metabolized by a bacterial tryptophanase (TnAse) from the gut microbiota to generate indole, indole-3-propionic acid (IPA), and indole-3-aldehyde (IAld). Indole is a precursor of the AhR agonist indoxyl-3-sulfate (I3S) [110]. Recently, dietary tryptophan was reported to protect mice against multiple sclerosis [108]. However, it has also been indicated that a high level of indole in a rat model increases the likelihood of developing brain dysfunctions, including anxiety and mood disorders [111].

Szczesniak et al. found that bacteria such as Faecalibacterium, Alistipes and Ruminococcus were correlated with depression, as well as the level of isovaleric acid, a type of volatile fatty acid (VFA) [112]. These associations probably occur because gut-derived VFAs can pass the BBB and further interact with synaptic neurotransmitters. Interestingly, Wu et al. revealed that although the plasma metabolome of vegans is significantly different from that of omnivores, the microbiota composition of these groups is similar [113].

One of the dietary tyrosine metabolites, 4-ethylphenylsulfate (4-EPS), is able to induce autism spectrum disorder (ASD)-like behaviors. However, following injection with Bacteroides fragilis, the gut microbiota produces reduced levels of neurotoxic metabolites, including 4-EPS, serum glycolate, and imidazole propionate, correcting gut permeability and ameliorating anxiety-like behavior [114].

Neuropsychiatric dysfunction

Mood, memory, and cognition were originally thought to be exclusively regulated by the CNS due to a variety of extrinsic factors such as hormonal fluctuations [115]. It is now becoming clear that many non-nervous system factors, including the immune system and the resident bacteria of the gastrointestinal tract, regulate not only our feelings and how we form, process, and store memories but also cognitive function-related microstructure and morphology. Psychogastroenterological studies have been performed to analyze the microbiota regulating resilience, optimism, mindfulness, and self-regulation and mastery [116]. Alteration of the gut microbiota regulates not only the synthesis of metabolites but also different neuroactive molecules and central neurotransmitters, such as melatonin, gamma-aminobutyric acid (GABA), serotonin, histamine, and acetylcholine [117]. Germ-free and antibiotic rodent models have shown that microbiota exposure can induce depression, anxiety and stress, decreases in social communication, increases in exploratory activity, and memory deterioration (Table 1).

Early life is an important period in the development of the nervous system of the host. The microbiota colonizes the host immediately after birth within a few weeks and forms organ-specific niches [132, 133]. The initial commensal microbiota gradually forms similar communities in adults in the following 2–3 years [134]. However, the process can be influenced by inflammation during this stage. As an important modulator of neurogenesis, microglia may play an inflammatory and detrimental role in neural development when activated by LPS. Such effects result in abnormal host behaviors and learning impairments later in adulthood [135]. The microbiota can facilitate the development of host neurological functions (i.e., the development of cognitive functions and memory). In a mouse model, long-term exposure to a western diet has been shown to not only cause obesity but also trigger systemic inflammatory responses to LPS and to further induce cognitive deficits such as poorer spatial memory [136]. Magnusson et al. indicated that high-energy food alters the composition of the microbiota and impacts working memory and cognitive flexibility, resulting in poorer long-term memory formation [137]. Infection by bacteria such as C. rodentium is another trigger that may generate stress-induced memory dysfunction in a rodent model [129].

Stress and depression

The gut microbiota has been shown to play critical roles in the pathogenesis of depression and anxiety-like behavior [138, 139]. Abnormal HPA hyperactivity in response to stress is associated with depressive episodes. Sudo et al. found that the HPA stress response is hyperactive in germ-free mice, but this hyperactivity can be reversed by Bifidobacterium infantis [121]. Plasma ACTH and corticosterone levels have been observed to be higher in GF mice than SPF mice when responding to stress. However, Diaz et al. revealed that GF mice exhibit increased plasma levels of tryptophan and serotonin compared with SPF mice [61], which is correlated with increased motor activity and reduced anxiety. Neufeld et al.’s results also demonstrated that GF mice exhibit anxiolytic behavior via increased expression of brain-derived neurotrophic factor (BDNF) and reduced serotonin 1A receptor levels in the hippocampus [122]. Anxiety and depression are typical complications in irritable bowel syndrome (IBS) patients, who show a higher prevalence of these conditions than healthy controls [140]. In addition to anxiety and depression, IBD patients exhibit mild verbal memory dysfunctions. The VFA isovaleric acid has been regarded as an important mediator of depression [112]. Gut-derived isovaleric acid can cross the BBB and interfere with synaptic neurotransmitter release. Isovaleric acid is positively correlated with saliva cortisol, which is strongly associated with depression in boys [141]. Bravo et al. have shown that GABA receptor expression in different brain areas can be altered by chronic treatment with Lactobacillus rhamnosus. This treatment further reduces stress-induced corticosterone levels and depression-like behaviors [119]. Stress-induced reduction of hippocampal neurogenesis can also be prevented by a probiotic combination of Lactobacillus helveticus strain R0052 and Bifidobacterium longum strain R0175 [142]. De Theije et al. showed that the effect of probiotics is highly strain specific. The administration of Campylobacter jejuni promotes depressive- or stress-like behaviors, while Bifidobacterium strains exert a decreasing effect on these behaviors [143].

Autism spectrum disorder

ASDs are characterized by abnormal communication and social behaviors, which begin in early childhood neurodevelopment. Gut problems or a history of gastrointestinal perturbations such as infection and anti- or pro-biotic intake in early childhood contributes to the disease development [144,145,146]. Gastrointestinal discomfort in ASD patients is usually thought to have a neurologic rather than a gastroenteric cause [147, 148]. However, recent studies have revealed that gut microflora alteration-related gastrointestinal symptoms are associated with mucosal inflammation [148, 149]. Anti-inflammatory and SCFA-synthesizing species such as Faecalibacterium species are decreased in ASD patients compared to controls [150]. Oral administration of Bacteroides fragilis (a commensal bacterium) can correct intestinal epithelial permeability caused by dysbiosis, leading to the modulation of several metabolites and ameliorated symptoms of ASD [114]. The Firmicutes/Bacteroides ratio and the composition of Fusobacteria or Verrucomicrobia are associated with ASDs. Lower levels of Bifidobacteria species, mucolytic bacteria, and Akkermansia muciniphila are found in children with ASD, while Lactobacillus, Bacteroides, Prevotella, and Alistipes are present at higher levels [145, 151, 152]. However, Desulfovibrio species, Bacteroides vulgatus, and Clostridia are over-represented in children with ASD with gastrointestinal symptoms compared with normal subjects with similar GI complaints [153, 154]. One hypothesis regarding the reoccurrence of ASD symptoms after oral vancomycin treatments is that Clostridia undergo spore formation to avoid eradication [145]. Although there is little direct causal evidence that the microbiota can cure ASD, the use of probiotic strains of Lactobacillus species and Bifidobacterium species has been shown to ameliorate gastrointestinal symptoms in children with ASD [119, 155]. Hsiao et al.’s research suggested that oral treatment with Bacteroides fragilis in a mouse model altered the microbial composition, improved gut permeability, and reduced defects in communicative and anxiety-like behaviors [114].

Pain and migraine

Pain is common in the general population, and the microbiota has shown to impact several types of pain, including spinal visceral pain in IBS [138, 156] and small intestinal bacterial overgrowth (SIBO) [157] as well as migraine [158] and sometimes headache [159]. Administration of antibiotics may induce gut dysbiosis and alter host-bacterial interactions, leading to colonic sensory and motor changes in a mouse model. These effects can be reflected by nociceptive markers such as CB2 and TLR7 [160]. Amaral et al. showed that inflammatory hypernociception induced by LPS, TNF-α, IL-1beta, and the chemokine CXCL1 is reduced in germ-free mice. This effect was similar to the induction by prostaglandins and dopamine [161]. It has been revealed by meta-analyses that Helicobacter pylori infection is associated with migraine [162]. Faraji et al. performed a randomized blinded clinical trial that demonstrated improvement of migraine associated with H. pylori eradication [158]. A recent study revealed that gut microbiota dysbiosis-induced chronic migraine-like pain are accomplished by up-regulating TNF-α level [163].

On the other hand, visceral pain can be effectively alleviated by probiotic treatment in animal models. Rousseaux et al. found that analgesic functions could be achieved by taking specific Lactobacillus strains orally. The resulting morphine-like effect was shown to be mediated by enhanced expression of intestinal epithelial μ-opioid and cannabinoid receptors [164]. Probiotic B. infantis 35624 and Lactobacillus farciminis were shown to exert visceral antinociceptive effects by altering central sensitization in rat models [165, 166]. L. farciminis can also attenuate stress-induced Fos expression in the spine, which explains the antinociceptive effect of this probiotic. In a clinical-alimentary study, O’Mahony et al. treated patients with probiotics and found that Lactobacillus salivarius UCC4331 significantly reduced pain and discomfort during the administration phase for one week, while B. infantis 35624 reduced pain and discomfort scores during both the administration and washout phases [167].

Neurodegenerative diseases

Neurodegenerative diseases are a collection of neurological diseases that are characterized by progressive loss of neurons, including AD, Parkinson’s disease (PD), amyotrophic lateral sclerosis (ALS) and multiple sclerosis (MS) [168]. Each of the neurodegenerative diseases has been reported to have unique pathologies and clinical features. Nevertheless, neuroinflammation and higher intestinal permeability are common characteristics of them [169]. Some of the peripheral inflammation factors such as TNF-α, iNOS, and IL-6 have been validated in the pathogenesis of the neurodegeneration in CNS [170, 171]. In this chapter, we will discuss how functional gastrointestinal disorders are critically linked to these neuropathies.

Parkinson’s disease

PD is a typical neurodegenerative disorder affecting more than 1% of the population over 65 years of age [172]. PD is thought to be caused by the interaction between environmental and genetic risk factors. This neuropathology is characterized by motor deficits and non-motor symptoms (NMS), which ultimately have an impact on quality of life [173].

Recently, the gut microflora has drawn increasing attention with respect to how it may be implicated in PD [173]. A variety of enteral dysfunctions are associated with PD, such as SIBO, malnutrition, H. pylori infection, and constipation [174]. In terms of the role of GI tracts pathology in PD, a higher frequency of α-synuclein detection is found in the patients than in controls from many researches [175]. Animal studies validated that resection of vagus nerve can stop transmission of α-synuclein from gastro intestine to the CNS [66, 176]. Bowel inflammation can also trigger neuroinflammation to promote dopaminergic neuronal loss in the rodent substantia-nigra tissue [177]. Forsyth and colleagues found that “leaky guts” and bowel inflammation affect the progression of PD [178]. The increased colonic permeability was found to be correlated with increased α-synuclein and E. coli accumulation in the sigmoid of PD patients [179].

Counts of butyrate-producing and anti-inflammatory bacterial genera such as Blautia, Coprococcus, and Roseburia are significantly lower in PD patients, while those of LPS-producing genera Oscillospira and Bacteroides are significantly higher [180]. The pro-inflammatory genus Ralstonia is significantly abundant in PD patient mucosae, implying that the inflammatory gut barrier is pathogenic. Scheperjans et al. revealed that the altered intestinal microbiota and the related motor phenotype could be applied to the diagnosis of PD [181]. The relative abundance of Prevotellaceae is significantly reduced in PD and has been validated as a very sensitive biomarker for PD diagnosis. A model based on multiple bacterial families and constipation status was shown to present 90.3% specificity in PD diagnosis. Ingestion of fermented milk for 4 weeks was proven to be effective in improving PD complications such as constipation [182]. Two studies have shown that anti-TNF therapy and immunosuppressants reduced PD risk [183, 184]. However, there is very limited clinical evidence of the beneficial effects of probiotics in the treatment of PD and further evidences are needed.

Alzheimer’s disease

AD, which is the most common degenerative disease, is characterized by a decline in cognitive skills, including memory, language, and problem solving, eventually resulting in dementia [185]. AD is pathologically characterized by neuroinflammation, accumulation of beta-amyloid (Aβ) plaque, and neurofibrillary tau tangles in the brain. Aβ (Aβ40 or Aβ42) are cleaved products from the amyloid precursor protein (APP). The Aβ polymerizes into fibrils in the CNS by self-aggregation and further triggers inflammation and neurotoxicity. Recent studies have demonstrated the role and impact of microbial dysfunction and infection on the aetiology of AD, especially the activation of neuroinflammation and the formation of amyloids.

Neuroinflammation factors, including IL-1beta, IL-6, and TNF-alpha, have been observed in AD patients [186, 187]. Gareau et al.’s work implied that memory loss and dysfunction are exacerbated by infection under exposure to acute stress [129]. Released LPS triggers the inflammation and promotes amyloid fibrillogenesis in the brain [188]. The microglia can recognize amyloid molecules by TLR4 and TLR2 for clearance. Interestingly, signaling of myeloid differentiation primary response 88 (MyD88) from microglial TLR2 is responsible for activation of TNF-α and nuclear factor kappa B (NF-κB) which also induces the formation of Aβ by promoting α-secretase and β-secretase, respectively [189].

As a generic term, amyloid denotes any insoluble, aggregation-prone, and lipoprotein-rich deposit that resembles carbohydrate starches [190]. Bacterial metabolites and products have recently been shown to worsen AD. In AD patients, bacteria-derived amyloids (curli, tau, Aβ, α-syn, and prion) can function as initiators to cross-seed and aggregate host amyloids [191]. Amyloids such as CsgA and Aβ42 can exhibit cerebral deposition and trigger a cascade of AD-related pathological events despite their dissimilarity of sequences [192]. It is reported that chronic H. pylori could trigger the release of both inflammatory mediators and amyloids in AD patients [193, 194]. H. pylori filtrate was shown to have the ability to induce the hyperphosphorylation of tau protein in a cell model [195]. E. coli has been reported to produce extracellular amyloids known as curli fibres, a major subunit of CsgA. Other amyloids produced by microbes include CsgA produced by Salmonella spp., FapC by Pseudomonas fluorescens, MccE492 by Klebsiella pneumonia, phenol-soluble Modulins by Staphylococcus aureus, TasA by Bacillus subtills, and Chaplins by Streptomyces coelicolor [190, 196, 197]. Harach et al. found a remarkable shift in the gut microbiota in fecal samples from an APP-transgenic mouse and reported that the microbiota contributed to the development of this neurodegenerative diseases. Intestinal germ-free APP transgenic mice were found to have a reduction of cerebral amyloid pathology compared to controls [198]. More recently, Chlamydia pneumoniae infection in astrocytes has been demonstrated to be involved in the generation of β-amyloid, which promotes AD [199]. Ingestion of probiotics has been reported to be beneficial in AD. Azm S et al. demonstrated that Lactobacilli and Bifidobacteria were effective in ameliorating memory and learning dysfunction in a β-amyloid-injected rodent model [200]. Wang and Liang et al. revealed that Lactobacillus fermentum NS9 and Lactobacillus helveticus NS8 alleviated ampicillin-induced spatial memory impairment and improved the spatial memory of chronic restraint stress [201, 202]. In a randomized clinical trial of probiotic treatment conducted in 60 AD patients, Akbari et al. showed that after 12 weeks of administration of Lactobacillus and Bifidobacterium species via fermented milk, mini-mental state examination (MMSE) scores improved significantly. Improvements in glucose and lipid metabolism were also observed, which were thought to enhance the cognitive assessment scoring [203]. The elimination of Helicobacter pylori by triple eradication therapy results in improvement of cognition parameters in AD patients [204]. It is promising that the use of pro- or antibiotics could be future therapeutic agents for AD. It has been demonstrated in a recent study that exercise and probiotics could reduce Aβ plaques in the hippocampus, improve cognitive performance, and finally, attenuate the development of Alzheimer's disease in the mouse model [205].

Amyotrophic lateral sclerosis

ALS is a fatal neurodegenerative disorder that affects the brain and spinal cord neurons and typically results in death. Most ALS patients die within 3 to 5 years due to respiratory paralysis [206]. The pathogenesis of ALS is proposed to be outcomes of genetic-environmental interactions. Studies on interactions between innate immune response and LPS have provided essential evidences of ALS pathogenesis [207,208,209]. More than a decade ago, it was proposed that gut-derived neurotoxins, including tetanus and botulinum toxins produced by Clostridia species, cause ALS [210, 211]. “Leaky gut” is also likely to be responsible for ALS [212]. More recently, Wu’s ALS mouse model revealed that the tight junction structure was damaged and that gut permeability was increased. Gut dysbiosis is also found in ALS mice, particularly in terms of reduced levels of butyrate-producing bacteria, including Butyrivibrio fibrisolvens and E. coli [213]. In the gut of ALS patients, butyrate-producing Oscillibacter, Anaerostipes, and Lachnospira counts were found to be reduced, while that of glucose-metabolizing Dorea was significantly increased [214]. Brenner et al. found the richness of OTUs to be significantly higher in an ALS group compared with a control group. However, the relative ratio of Bacteroidetes/Firmicutes did show a significant difference between ALS patients and controls [215]. Supplementation of the diet with 2% butyrate in drinking water in an ALS mouse model resulted in improved gut integrity and survival [216]. Mazzini et al. revealed unique bacterial profiles in ALS patients compared to the controls. Higher E. coli and Enterobacteria abundance, and lower Clostridium was found in ALS participants [217]. These results imply that anti-inflammatory SCFAs produced by gut microbiota are potential therapeutic agents affecting ALS progression. Mazzini et al. further conducted a clinical trial of bacteriotherapy aimed at understanding the effect of Lactobacillus strains [217]. However, more direct evidence and results are needed to clarify how the gut microbiota improves or aggravates ALS.

Multiple sclerosis

MS is a type of autoimmunity-induced neurodegenerative disease in the spinal column and CNS. The environmental factors contribute profoundly to pathogenesis of this demyelinating disease, including obesity, smoking, viruses, and vitamin D [218]. Alterations in the microbiome and prevalence of “leaky gut” have been found in MS patients and experimental autoimmune encephalomyelitis (EAE) animal, the most commonly used inflammatory demyelinating disease model [219, 220]. The immunological changes in EAE are characterized by increasing proinflammatory cell infiltration and impaired Treg function [221]. The favorable gut microbiota can regulate permeability of BBB, limit astrocyte pathogenicity, and activate microglia [222]. In the EAE model, the Bifidobacterium and lactic acid-producing bacteria such as of Lactobacillus are able to reduce severity of EAE symptoms [223, 224]. The abundance of Archaea is high in MS while Firmicutes and Bacteroidetes phyla are lower or even depleted [218]. The Bacteroides and Clostridia species are especially responsible for the induction of FoxP3+ Tregs in suppression of inflammation [222]. One small longitudinal study found that the gut microbiota profiles, especially Fusobacteria were associated with future relapse risk in MS [225]. Psuedomonas, Haemophilus, Blautia, and Dorea genera were detected to be increased in MS patients, while Parabacteroides, Adlercreutzia and Prevotella genera were much lower [219]. Clostridiales order were restored after MS treatment with glatiramer acetate including Bacteroidaceae, Faecalibacterium, Ruminococcus, Lactobacillaceae, and Clostridium [226]. Ochoa-Reparaz et al. unraveled that oral administration of antibiotics can delay the pathogenesis of EAE. However, intraperitoneal injection did not significantly impact the outcomes [227]. This implies changes in intestinal microbiota ecosystem are associated with MS development. Other studies also validated that probiotic treatment and fecal microbial transplantation can achieve similar effect [228, 229].

Cerebral vascular diseases

Cerebrovascular diseases are a variety of circulatory diseases that affect cerebral circulation and, thus, cause brain damage. The most common presentations of cerebrovascular disease are ischemic stroke, hemorrhagic stroke, and intracranial arteriovenous malformation (AVM). The GI microflora and infection have been indicated to impact the host immune system and ischemic stroke processes. Infection and inflammation at plaque lesions along with imbalanced carnitine, cholesterol and fat metabolism by intestinal microflora ultimately contributed to atherosclerosis.

Atherosclerosis

Fernandes et al. revealed that oral Streptococcus mutans is ubiquitous in the atherosclerotic plaques of patients with vascular disease [230]. Apfalter et al. identified traces of Chlamydia pneumoniae in carotid artery atherosclerosis using a nested PCR-based approach [231]. Mitra et al.’s metagenomic study of carotid atherosclerosis plaques showed that 2–16% of the sequencing reads from plaque tissue came from bacteria, including Lactobacillus rhamnosus and Neisseria polysaccharea. The bacterial content is higher in patients with ischemic symptoms. Acidovorax spp. and H. pylori cells were also detected by fluorescence in situ hybridization (FISH) in atherosclerotic tissue [232]. Karlsson et al. sequenced the gut metagenomes of patients with symptomatic atherosclerosis and healthy subjects. The genus Collinsella was observed to be enriched in carotid stenotic patients, whereas Roseburia and Eubacterium were more abundant in healthy controls [233].The gut microbiota has been suggested to transform dietary choline, lecithin, or carnitine into TMAO and, thus, cause vascular atherosclerosis by affecting lipid and hormonal homeostasis [89, 234]. The carnitine-butyrobetaine-trimethylamine-N-oxide pathway has been found to be associated with carotid atherosclerosis [235]. Stimulation of monocyte by LPS can be a critical step of the formation of foam cell in atherosclerotic plaque by either inducing inflammation or triggering LDL uptake [236, 237]. A series of probiotic-based therapy attempts have been in progress, including human trials using L. acidophilus 145, B. longum 913 [238], L. acidophilus and B. bifidum [239] to restore HDL/LDL ratio, and mouse experiments using L. plantarum ZDY04 against TMAO [240].

Stroke

Benakis et al. showed that infarction-induced ischemic brain injury could be reduced by antibiotic administration. The antibiotic-induced alterations in the gut microbiota could increase regulatory T cells and decrease IL-17+ γδ T cells, which suppress the trafficking of effector T cells after stroke. Interestingly, the gut microbiota-associated infarction model can be transmitted and reproduced by fecal transplantation [241]. Systemic exposure to Porphyromonas gingivalis has been linked to an increased risk of ischemic stroke [242]. Kawato et al. revealed that continual venous injection of Gram-negative bacteria might accelerate stroke in SHRSP (spontaneously hypertensive stroke-prone) rats, probably due to LPS-induced oxidative stress responses [243]. Zhu et al. discovered that TMAO is associated with platelet hyperactivity and thrombosis risk [90]. Their following study validated in a short-term cohort that an omnivorous diet could generate a higher TMAO content in blood than was induced by a vegan diet, which was more likely to promote the formation of blood clots. Their study suggested that the use of low doses of aspirin was helpful to alleviate platelet aggregation caused by TMAO [244]. Yin et al. revealed that opportunistic gut-derived pathogens such as Enterobacter, Megasphaera, Oscillibacter, and Desulfovibrio were enriched in patients experiencing stroke and transient ischemic attack, whereas beneficial genera including Bacteroides, Prevotella, and Faecalibacterium were less abundant. Paradoxically, Yin et al. showed that TMAO levels were lower in patients than in controls [245].

Arteriovenous malformation

There is no direct causal relationship between the microbiota and AVM onset in humans, while animal models have implied a pivotal role of the microflora in AVM pathophysiology and pathogenesis. Shikata et al. used antibiotics to deplete the gut microbiota in an aneurysm mouse model, and aneurysm induction was drastically reduced due to less macrophage infiltration and cytokine secretion [246]. Cerebral cavernous malformation (CCM) is a common type of vascular malformation resulting in hemorrhagic stroke and seizure [247]. Tang et al. showed that stimulation of TLR4 by bacteria or LPS accelerates CCM formation, whereas the use of germ-free mice and antibiotics use in mice can prevent CCM. The gut microbiome and endothelial TLR4 act as critical stimulants, suggesting their potential use as novel strategies in CCM therapy [248]. Interestingly, Winek et al.’s paradoxical results indicated that a broad-spectrum antibiotic-treated gut microbiota worsens inflammation and stroke in a murine model [249]. However, Evangelo Boumis et al. found that consumption of probiotics such as Lactobacillus rhamnosus may impose a serious risk of infection in patients with special susceptibility factors, and antibiotic prevention should be considered [250]. These findings implied that specific microbiota and antibiotic use result in different outcomes.

Conclusions and perspectives

It is now gradually being accepted that the gut microbiota is important in both the maintenance of the intestinal flora and brain physiology. Through the immune system, endocrine system, and bacterial metabolites, the gut microbiota regulates neurotransmission and vascular barriers, which in turn alter host neuropsychological function, cognition, and cerebral vascular physiology. Research and development of potential therapeutic targets are also in progresses. The brain diseases, alteration of gut microbiota, evidenced mechanisms, and potential probiotic-based therapeutics are summarized in Table 2. However, there are still challenges in terms of the experimental design, subjects, models, analytical approach, pipeline, and quality control protocols used in metabolomics studies.

Thus far, evidence has revealed clear associations between microbiota and host physiology, rather than demonstrating causal relationships. Since there are multiple confounding variables in human fecal experiments, larger sample-size studies are needed for metagenomic biomarker screening. Such studies are more reliable when exposure, demographics, diet, and socioeconomic factors are considered. However, even in population-based metagenomic analyses, the outcome variables are largely influenced by irreducible variables and confounders, while the composition of the microbiome can be explained by limited effects (10–20%) [252,253,254]. Another obstacle in current microbiota-based translational medicine is the mild and long-term of effects observed in terms of cognitive or psychological function. It might take months to years of probiotic and microbiota-based therapeutics to influence neuropsychiatric diseases, while the effect of the microbiota on host coagulation can be observed much more rapidly.

In addition to human cohort and cross-sectional studies, animal models provide essential evidence to explain how specific microbes affect the host. Animal models, especially murine models, have been widely adopted in pre-clinical experiments to validate the functions of specific microbial species. Early animal studies were established in germ-free animals to reveal associations between host physiology and the effect of the microbiota [255]. Specific microorganisms colonizing germ-free animals, probiotic use and fecal microbiota transplantation (FMT) approaches are widely used to elucidate the specific traits and functions of the microbiota. Antibiotic-treated animal models are alternatives for studying the microbial depletion effect on wild-type animals with mature immunity [20]. However, there are still many obstacles in the practice of translational medicine using conclusions about the microbiome from animal models, including issues related to genomic background, intestinal differences, dietary habits, and other life exposures. For example, although the human genome shares more than 85% of its genomic sequences with the mouse genome, the expression patterns and protein functions of these species are not exactly the same [256,257,258,259]. In terms of intestinal structure, mice present a relatively larger cecum and small intestine than humans. On the other hand, there are more circular folds (i.e., plicae circularis) in the human small intestine that increase the surface area, whereas the appearance of the mouse mucosa surface is smoother [259, 260]. Life experience is another issue that arises during data analysis, as humans and animals experience different life histories, exercise regimes, circadian cycles, social pressures, and especially food contents. Normally, the diet and chewing in animal experiments are nutritionally controlled and monotonous, while the composition of the human diet varies daily. These diet-related confounders may cause challenges during replication and translation of a model into clinical trials. However, quantitative cohort studies have provided stronger evidence than retrospective questionnaires in human studies, and smaller sample sizes are sometimes adequate to validate a hypothesis [244, 261].

The choice of microbiome analysis approaches and their technical stability are additional major challenges. The DNA extraction method, library preparation protocol, sequencer and analytic pipeline employed contribute to the observed biological variation even within a given specimen [262]. Recently, large-scale comparative studies identified the importance of sample homogenization, aliquoting and analytical pipelines in data processing [263, 264]. It is also worth noting that the results from 16S and WMS analyses are not fully replicable, since 16S sequencing largely depends on variable region selection, while WMS identifies and quantitates fragments from the entire genome of all organisms in the sample. Therefore, each protocol exhibits a preference for specific taxonomic assignments, which might cause further misinterpretations [265,266,267,268]. Furthermore, most 16S sequencing protocols obtain phylum- or genus-level resolution of taxa, whereas the WMS protocol can provide species or even strain-level information [24, 269].

Although far from being perfect, the gut microbiota-based therapy is a promising potential approach to be used in future therapies for brain diseases. Doctors and scientists are ready to think outside the pillbox in accord with the suggestion of Hippocrates (400 BC) to “Let food be thy medicine and medicine be thy food” [270]. Scientists are also pushing the frontier of the application of the microbiota in the diagnosis, treatment, and prognosis of brain diseases. The robust data produced from MWAS, metabolomics, and multi-omics are hopefully forming a framework that will enable the integration of psychological care, cerebrovascular care, and gastroenterological care into therapies.

Availability of data and materials

Not applicable

Abbreviations

- 4-EPS:

-

4-ethylphenylsulfate

- AD:

-

Alzheimer’s disease

- AHR:

-

Aryl hydrocarbon receptor

- ALS:

-

Amyotrophic lateral sclerosis

- APP:

-

Aβ precursor protein

- ASDs:

-

Autism spectrum disorders

- AVM:

-

Arteriovenous malformation

- Aβ:

-

Beta-amyloid

- BBB:

-

Blood–brain barrier

- CCM:

-

Cerebral cavernous malformation

- CNS:

-

Central nervous system

- DASH:

-

Dietary approach to stop hypertension

- DMB:

-

3-dimethyl-1-butanol

- EAE:

-

Experimental autoimmune encephalomyelitis

- FISH:

-

Fluorescence in situ hybridization

- FMT:

-

Fecal microbiota transplantation

- GABA:

-

Gamma-aminobutyric acid

- HFD:

-

High-fat diet

- HFHC:

-

High-fat and high-cholesterol diet

- HMP:

-

Human Microbiome Project

- HPA:

-

Hypothalamus-pituitary-adrenal gland axis

- I3S:

-

Indoxyl-3-sulfate

- IAld:

-

Indole-3-aldehyde

- IBD:

-

Inflammatory bowel diseases

- IBS:

-

Irritable bowel syndrome

- ILC3:

-

Group 3 innate lymphoid cells

- IPA:

-

Indole-3-propionic acid

- ITS:

-

Internal transcribed spacer

- LCFAs:

-

Long-chain fatty acids

- LPS:

-

Lipopolysaccharides

- LTA:

-

Lipoteichoic acid

- MeDi:

-

Mediterranean diet

- MetaHIT:

-

Metagenomics of the human intestinal tract

- MIND:

-

Mediterranean-DASH Intervention for Neurodegenerative Delay

- MMSE:

-

Mini-mental state examination

- MRI:

-

Magnetic resonance imaging

- MS:

-

Multiple sclerosis

- MWAS:

-

Metagenome-wide association studies

- NGS:

-

Next-generation sequencing

- NMRS:

-

Nuclear magnetic resonance spectroscopy

- NMS:

-

Non-motor symptoms

- PAMPs:

-

Pathogen-associated molecular patterns

- PD:

-

Parkinson’s disease

- PRRs:

-

Pattern recognition receptors

- rRNA:

-

Ribosomal RNA

- SCFAs:

-

Short-chain fatty acids

- SHRSP:

-

Spontaneously hypertensive stroke-prone

- SIBO:

-

Small intestinal bacterial overgrowth

- SSU:

-

Small subunit

- TLR:

-

Toll-like receptor

- TMA:

-

Trimethylamine

- TMAO:

-

Trimethylamine oxide

- TnAse:

-

Tryptophanase

- Tregs:

-

Regulatory T cells

- VFA:

-

Volatile fatty acid

References

Madigan MT. Brock biology of microorganisms. 13th ed. San Francisco: Benjamin Cummings; 2012.

Shulman ST, Friedmann HC, Sims RH. Theodor Escherich: the first pediatric infectious diseases physician? Clinical infectious diseases : an official publication of the Infectious Diseases Society of America. 2007;45(8):1025–9.

Podolsky SH. Metchnikoff and the microbiome. Lancet. 2012;380(9856):1810–1.

Tirosh I, Izar B, Prakadan SM, Wadsworth MH 2nd, Treacy D, Trombetta JJ, Rotem A, Rodman C, Lian C, Murphy G, et al. Dissecting the multicellular ecosystem of metastatic melanoma by single-cell RNA-seq. Science. 2016;352(6282):189–96.

Tan TZ, Miow QH, Miki Y, Noda T, Mori S, Huang RY, Thiery JP. Epithelial-mesenchymal transition spectrum quantification and its efficacy in deciphering survival and drug responses of cancer patients. EMBO molecular medicine. 2014;6(10):1279–93.

Qin J, Li Y, Cai Z, Li S, Zhu J, Zhang F, Liang S, Zhang W, Guan Y, Shen D, et al. A metagenome-wide association study of gut microbiota in type 2 diabetes. Nature. 2012;490(7418):55–60.

Forslund K, Hildebrand F, Nielsen T, Falony G, Le Chatelier E, Sunagawa S, Prifti E, Vieira-Silva S, Gudmundsdottir V, Pedersen HK, et al. Disentangling type 2 diabetes and metformin treatment signatures in the human gut microbiota. Nature. 2015;528(7581):262–6.

Manichanh C, Rigottier-Gois L, Bonnaud E, Gloux K, Pelletier E, Frangeul L, Nalin R, Jarrin C, Chardon P, Marteau P, et al. Reduced diversity of faecal microbiota in Crohn's disease revealed by a metagenomic approach. Gut. 2006;55(2):205–11.

Carroll IM, Ringel-Kulka T, Keku TO, Chang YH, Packey CD, Sartor RB, Ringel Y. Molecular analysis of the luminal- and mucosal-associated intestinal microbiota in diarrhea-predominant irritable bowel syndrome. American journal of physiology Gastrointestinal and liver physiology. 2011;301(5):G799–807.

Zeller G, Tap J, Voigt AY, Sunagawa S, Kultima JR, Costea PI, Amiot A, Bohm J, Brunetti F, Habermann N, et al. Potential of fecal microbiota for early-stage detection of colorectal cancer. Molecular systems biology. 2014;10:766.

De Angelis M, Francavilla R, Piccolo M, De Giacomo A, Gobbetti M. Autism spectrum disorders and intestinal microbiota. Gut microbes. 2015;6(3):207–13.

Rosenfeld CS. Microbiome disturbances and autism spectrum disorders. Drug metabolism and disposition: the biological fate of chemicals. 2015;43(10):1557–71.

Winek K, Dirnagl U, Meisel A. The Gut Microbiome as Therapeutic target in central nervous system diseases: implications for stroke. Neurotherapeutics : the journal of the American Society for Experimental NeuroTherapeutics. 2016;13(4):762–74.

Collins SM, Surette M, Bercik P. The interplay between the intestinal microbiota and the brain. Nature reviews Microbiology. 2012;10(11):735–42.

Neunlist M, Van Landeghem L, Mahe MM, Derkinderen P, Des Varannes SB, Rolli-Derkinderen M. The digestive neuronal-glial-epithelial unit: a new actor in gut health and disease. Nature reviews Gastroenterology & Hepatology. 2013;10(2):90–100.

Furness JB. The enteric nervous system and neurogastroenterology. Nature Reviews Gastroenterology & Hepatology. 2012;9(5):286–94.

Matteoli G, Boeckxstaens GE. The vagal innervation of the gut and immune homeostasis. Gut. 2013;62(8):1214–22.

Wang Y, Kasper LH. The role of microbiome in central nervous system disorders. Brain, behavior, and immunity. 2014;38:1–12.

Petra AI, Panagiotidou S, Hatziagelaki E, Stewart JM, Conti P, Theoharides TC. Gut-microbiota-brain axis and its effect on neuropsychiatric disorders with suspected immune dysregulation. Clinical therapeutics. 2015;37(5):984–95.

Knight R, Vrbanac A, Taylor BC, Aksenov A, Callewaert C, Debelius J, Gonzalez A, Kosciolek T, McCall LI, McDonald D, et al. Best practices for analysing microbiomes. Nature reviews Microbiology. 2018;16(7):410–22.

Woese CR, Fox GE. Phylogenetic structure of the prokaryotic domain: the primary kingdoms. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 1977;74(11):5088–90.

Woese CR, Stackebrandt E, Macke TJ, Fox GE. A phylogenetic definition of the major eubacterial taxa. Systematic and applied microbiology. 1985;6:143–51.

Wilson KH, Blitchington RB. Human colonic biota studied by ribosomal DNA sequence analysis. Appl Environ Microbiol. 1996;62(7):2273–8.

Wang Q, Garrity GM, Tiedje JM, Cole JR. Naive Bayesian classifier for rapid assignment of rRNA sequences into the new bacterial taxonomy. Appl Environ Microbiol. 2007;73(16):5261–7.

Hillmann B, Al-Ghalith GA, Shields-Cutler RR, Zhu Q, Gohl DM, Beckman KB, Knight R, Knights D. Evaluating the information content of shallow shotgun metagenomics. mSystems. 2018;3(6).

Johnson JS, Spakowicz DJ, Hong BY, Petersen LM, Demkowicz P, Chen L, Leopold SR, Hanson BM, Agresta HO, Gerstein M, et al. Evaluation of 16S rRNA gene sequencing for species and strain-level microbiome analysis. Nat Commun. 2019;10(1):5029.

Breitbart M, Salamon P, Andresen B, Mahaffy JM, Segall AM, Mead D, Azam F, Rohwer F. Genomic analysis of uncultured marine viral communities. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 2002;99(22):14250–5.

Gillespie DE, Brady SF, Bettermann AD, Cianciotto NP, Liles MR, Rondon MR, Clardy J, Goodman RM, Handelsman J. Isolation of antibiotics turbomycin A and B from a metagenomic library of soil microbial DNA. Applied and environmental microbiology. 2002;68(9):4301–6.

Tyson GW, Chapman J, Hugenholtz P, Allen EE, Ram RJ, Richardson PM, Solovyev VV, Rubin EM, Rokhsar DS, Banfield JF. Community structure and metabolism through reconstruction of microbial genomes from the environment. Nature. 2004;428(6978):37–43.

Wang J, Jia H. Metagenome-wide association studies: fine-mining the microbiome. Nature reviews Microbiology. 2016;14(8):508–22.

Franzosa EA, Hsu T, Sirota-Madi A, Shafquat A, Abu-Ali G, Morgan XC, Huttenhower C. Sequencing and beyond: integrating molecular 'omics' for microbial community profiling. Nature reviews Microbiology. 2015;13(6):360–72.

Heyer R, Schallert K, Zoun R, Becher B, Saake G, Benndorf D. Challenges and perspectives of metaproteomic data analysis. Journal of biotechnology. 2017;261:24–36.

Griffin JL, Wang X, Stanley E. Does our gut microbiome predict cardiovascular risk? A review of the evidence from metabolomics. Circulation Cardiovascular genetics. 2015;8(1):187–91.

Smirnov KS, Maier TV, Walker A, Heinzmann SS, Forcisi S, Martinez I, Walter J, Schmitt-Kopplin P. Challenges of metabolomics in human gut microbiota research. International journal of medical microbiology : IJMM. 2016;306(5):266–79.

Arrieta MC, Finlay BB. The commensal microbiota drives immune homeostasis. Front Immunol. 2012;3:33.

Okada H, Kuhn C, Feillet H, Bach JF. The 'hygiene hypothesis' for autoimmune and allergic diseases: an update. Clin Exp Immunol. 2010;160(1):1–9.

Medzhitov R, Janeway C Jr. Innate immune recognition: mechanisms and pathways. Immunological reviews. 2000;173:89–97.

Janeway CA Jr. Approaching the asymptote? Evolution and revolution in immunology. Cold Spring Harbor symposia on quantitative biology. 1989;54(Pt 1):1–13.

Konig J, Wells J, Cani PD, Garcia-Rodenas CL, MacDonald T, Mercenier A, Whyte J, Troost F, Brummer RJ. Human intestinal barrier function in health and disease. Clinical and translational gastroenterology. 2016;7(10):e196.

Wells JM, Brummer RJ, Derrien M, MacDonald TT, Troost F, Cani PD, Theodorou V, Dekker J, Meheust A, de Vos WM, et al. Homeostasis of the gut barrier and potential biomarkers. American journal of physiology Gastrointestinal and liver physiology. 2017;312(3):G171–93.

Okun MS. Deep-brain stimulation for Parkinson's disease. The New England journal of medicine. 2012;367(16):1529–38.

Rolls A, Shechter R, London A, Ziv Y, Ronen A, Levy R, Schwartz M. Toll-like receptors modulate adult hippocampal neurogenesis. Nature cell biology. 2007;9(9):1081–8.

Shechter R, Ronen A, Rolls A, London A, Bakalash S, Young MJ, Schwartz M. Toll-like receptor 4 restricts retinal progenitor cell proliferation. The Journal of cell biology. 2008;183(3):393–400.

Okun E, Griffioen KJ, Son TG, Lee JH, Roberts NJ, Mughal MR, Hutchison E, Cheng A, Arumugam TV, Lathia JD, et al. TLR2 activation inhibits embryonic neural progenitor cell proliferation. Journal of neurochemistry. 2010;114(2):462–74.

Keohane A, Ryan S, Maloney E, Sullivan AM, Nolan YM. Tumour necrosis factor-alpha impairs neuronal differentiation but not proliferation of hippocampal neural precursor cells: role of Hes1. Molecular and cellular neurosciences. 2010;43(1):127–35.

Okun E, Barak B, Saada-Madar R, Rothman SM, Griffioen KJ, Roberts N, Castro K, Mughal MR, Pita MA, Stranahan AM, et al. Evidence for a developmental role for TLR4 in learning and memory. PloS one. 2012;7(10):e47522.

Wang S, Zhang X, Zhai L, Sheng X, Zheng W, Chu H, Zhang G. Atorvastatin attenuates cognitive deficits and neuroinflammation induced by Abeta1-42 involving modulation of TLR4/TRAF6/NF-kappaB pathway. Journal of molecular neuroscience : MN. 2018;64(3):363–73.

Honda K, Littman DR. The microbiota in adaptive immune homeostasis and disease. Nature. 2016;535(7610):75–84.

Atarashi K, Tanoue T, Shima T, Imaoka A, Kuwahara T, Momose Y, Cheng G, Yamasaki S, Saito T, Ohba Y, et al. Induction of colonic regulatory T cells by indigenous Clostridium species. Science. 2011;331(6015):337–41.

Smith PM, Howitt MR, Panikov N, Michaud M, Gallini CA, Bohlooly YM, Glickman JN, Garrett WS. The microbial metabolites, short-chain fatty acids, regulate colonic Treg cell homeostasis. Science. 2013;341(6145):569–73.

Mazmanian SK, Liu CH, Tzianabos AO, Kasper DL. An immunomodulatory molecule of symbiotic bacteria directs maturation of the host immune system. Cell. 2005;122(1):107–18.

Hirota K, Turner JE, Villa M, Duarte JH, Demengeot J, Steinmetz OM, Stockinger B. Plasticity of Th17 cells in Peyer's patches is responsible for the induction of T cell-dependent IgA responses. Nature immunology. 2013;14(4):372–9.

Ivanov II, McKenzie BS, Zhou L, Tadokoro CE, Lepelley A, Lafaille JJ, Cua DJ, Littman DR. The orphan nuclear receptor RORgammat directs the differentiation program of proinflammatory IL-17+ T helper cells. Cell. 2006;126(6):1121–33.

Ivanov II, Frutos Rde L, Manel N, Yoshinaga K, Rifkin DB, Sartor RB, Finlay BB, Littman DR. Specific microbiota direct the differentiation of IL-17-producing T-helper cells in the mucosa of the small intestine. Cell host & microbe. 2008;4(4):337–49.

Ishigame H, Kakuta S, Nagai T, Kadoki M, Nambu A, Komiyama Y, Fujikado N, Tanahashi Y, Akitsu A, Kotaki H, et al. Differential roles of interleukin-17A and -17F in host defense against mucoepithelial bacterial infection and allergic responses. Immunity. 2009;30(1):108–19.

Horai R, Zarate-Blades CR, Dillenburg-Pilla P, Chen J, Kielczewski JL, Silver PB, Jittayasothorn Y, Chan CC, Yamane H, Honda K, et al. Microbiota-dependent activation of an autoreactive T cell receptor provokes autoimmunity in an immunologically privileged site. Immunity. 2015;43(2):343–53.

Berer K, Mues M, Koutrolos M, Rasbi ZA, Boziki M, Johner C, Wekerle H, Krishnamoorthy G. Commensal microbiota and myelin autoantigen cooperate to trigger autoimmune demyelination. Nature. 2011;479(7374):538–41.

McGeachy MJ, Chen Y, Tato CM, Laurence A, Joyce-Shaikh B, Blumenschein WM, McClanahan TK, O'Shea JJ, Cua DJ. The interleukin 23 receptor is essential for the terminal differentiation of interleukin 17-producing effector T helper cells in vivo. Nature immunology. 2009;10(3):314–24.

Coccia M, Harrison OJ, Schiering C, Asquith MJ, Becher B, Powrie F, Maloy KJ. IL-1beta mediates chronic intestinal inflammation by promoting the accumulation of IL-17A secreting innate lymphoid cells and CD4(+) Th17 cells. The Journal of experimental medicine. 2012;209(9):1595–609.

Schulte-Herbruggen O, Quarcoo D, Meisel A, Meisel C. Differential affection of intestinal immune cell populations after cerebral ischemia in mice. Neuroimmunomodulation. 2009;16(3):213–8.

Diaz Heijtz R, Wang S, Anuar F, Qian Y, Bjorkholm B, Samuelsson A, Hibberd ML, Forssberg H, Pettersson S. Normal gut microbiota modulates brain development and behavior. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 2011;108(7):3047–52.

Obermeier B, Daneman R, Ransohoff RM. Development, maintenance and disruption of the blood-brain barrier. Nature medicine. 2013;19(12):1584–96.

Daneman R, Prat A. The blood-brain barrier. Cold Spring Harbor perspectives in biology. 2015;7(1):a020412.

Acharya NK, Levin EC, Clifford PM, Han M, Tourtellotte R, Chamberlain D, Pollaro M, Coretti NJ, Kosciuk MC, Nagele EP, et al. Diabetes and hypercholesterolemia increase blood-brain barrier permeability and brain amyloid deposition: beneficial effects of the LpPLA2 inhibitor darapladib. Journal of Alzheimer’s disease : JAD. 2013;35(1):179–98.

Fiorentino M, Sapone A, Senger S, Camhi SS, Kadzielski SM, Buie TM, Kelly DL, Cascella N, Fasano A. Blood-brain barrier and intestinal epithelial barrier alterations in autism spectrum disorders. Molecular autism. 2016;7:49.

Holmqvist S, Chutna O, Bousset L, Aldrin-Kirk P, Li W, Bjorklund T, Wang ZY, Roybon L, Melki R, Li JY. Direct evidence of Parkinson pathology spread from the gastrointestinal tract to the brain in rats. Acta neuropathologica. 2014;128(6):805–20.

Braniste V, Al-Asmakh M, Kowal C, Anuar F, Abbaspour A, Toth M, Korecka A, Bakocevic N, Ng LG, Kundu P, et al. The gut microbiota influences blood-brain barrier permeability in mice. Science translational medicine. 2014;6(263):263ra158.

Lee SW, Kim WJ, Choi YK, Song HS, Son MJ, Gelman IH, Kim YJ, Kim KW. SSeCKS regulates angiogenesis and tight junction formation in blood-brain barrier. Nature medicine. 2003;9(7):900–6.

Spadoni I, Fornasa G, Rescigno M. Organ-specific protection mediated by cooperation between vascular and epithelial barriers. Nature reviews Immunology. 2017;17(12):761–73.

Luczynski P, McVey Neufeld KA, Oriach CS, Clarke G, Dinan TG, Cryan JF. Growing up in a bubble: using germ-free animals to assess the influence of the gut microbiota on brain and behavior. The international journal of neuropsychopharmacology. 2016;19(8).

Bao CH, Liu P, Liu HR, Wu LY, Shi Y, Chen WF, Qin W, Lu Y, Zhang JY, Jin XM, et al. Alterations in brain grey matter structures in patients with Crohn's disease and their correlation with psychological distress. Journal of Crohn's & colitis. 2015;9(7):532–40.

Mrakotsky C AR, Watson C, Vu C, Matos A, Friel S, Rivkin M, Snapper S: New Evidence for structural brain differences in pediatric Crohn's disease: impact of underlying disease factors. Inflammatory bowel diseases 2016, Mar; 22 Suppl 1:S6-S7.

Fernandez-Real JM, Serino M, Blasco G, Puig J, Daunis-i-Estadella J, Ricart W, Burcelin R, Fernandez-Aranda F, Portero-Otin M. Gut microbiota interacts with brain microstructure and function. The Journal of clinical endocrinology and metabolism. 2015;100(12):4505–13.

Vipperla K, O'Keefe SJ. The microbiota and its metabolites in colonic mucosal health and cancer risk. Nutrition in clinical practice : official publication of the American Society for Parenteral and Enteral Nutrition. 2012;27(5):624–35.

Luna RA, Foster JA. Gut brain axis: diet microbiota interactions and implications for modulation of anxiety and depression. Current opinion in biotechnology. 2015;32:35–41.

Evrensel A, Ceylan ME. The gut-brain axis: the missing link in depression. Clinical psychopharmacology and neuroscience : the official scientific journal of the Korean College of Neuropsychopharmacology. 2015;13(3):239–44.

Pistollato F, Iglesias RC, Ruiz R, Aparicio S, Crespo J, Lopez LD, Manna PP, Giampieri F, Battino M. Nutritional patterns associated with the maintenance of neurocognitive functions and the risk of dementia and Alzheimer's disease: a focus on human studies. Pharmacological research. 2018;131:32–43.

Dominguez LJ, Barbagallo M, Munoz-Garcia M, Godos J, Martinez-Gonzalez MA. Dietary patterns and cognitive decline: key features for prevention. Current pharmaceutical design. 2019;25(22):2428–42.

Tangney CC, Li H, Wang Y, Barnes L, Schneider JA, Bennett DA, Morris MC. Relation of DASH- and Mediterranean-like dietary patterns to cognitive decline in older persons. Neurology. 2014;83(16):1410–6.

Harrison CA, Taren D. How poverty affects diet to shape the microbiota and chronic disease. Nature reviews Immunology. 2018;18(4):279–87.

Hildebrandt MA, Hoffmann C, Sherrill-Mix SA, Keilbaugh SA, Hamady M, Chen YY, Knight R, Ahima RS, Bushman F, Wu GD. High-fat diet determines the composition of the murine gut microbiome independently of obesity. Gastroenterology. 2009;137(5):1716–1724 e1711-1712.

Perry RJ, Peng L, Barry NA, Cline GW, Zhang D, Cardone RL, Petersen KF, Kibbey RG, Goodman AL, Shulman GI. Acetate mediates a microbiome-brain-beta-cell axis to promote metabolic syndrome. Nature. 2016;534(7606):213–7.

Turnbaugh PJ, Ridaura VK, Faith JJ, Rey FE, Knight R, Gordon JI. The effect of diet on the human gut microbiome: a metagenomic analysis in humanized gnotobiotic mice. Sci Transl Med. 2009;1(6):6ra14.

Li Q, Lauber CL, Czarnecki-Maulden G, Pan Y, Hannah SS. Effects of the dietary protein and carbohydrate ratio on gut microbiomes in dogs of different body conditions. MBio. 2017:8(1).

Wu GD, Chen J, Hoffmann C, Bittinger K, Chen YY, Keilbaugh SA, Bewtra M, Knights D, Walters WA, Knight R, et al. Linking long-term dietary patterns with gut microbial enterotypes. Science. 2011;334(6052):105–8.

De Filippis F, Pellegrini N, Vannini L, Jeffery IB, La Storia A, Laghi L, Serrazanetti DI, Di Cagno R, Ferrocino I, Lazzi C, et al. High-level adherence to a Mediterranean diet beneficially impacts the gut microbiota and associated metabolome. Gut. 2016;65(11):1812–21.

Li JM, Yu R, Zhang LP, Wen SY, Wang SJ, Zhang XY, Xu Q, Kong LD. Dietary fructose-induced gut dysbiosis promotes mouse hippocampal neuroinflammation: a benefit of short-chain fatty acids. Microbiome. 2019;7(1):98.

Wang Z, Klipfell E, Bennett BJ, Koeth R, Levison BS, Dugar B, Feldstein AE, Britt EB, Fu X, Chung YM, et al. Gut flora metabolism of phosphatidylcholine promotes cardiovascular disease. Nature. 2011;472(7341):57–63.

Koeth RA, Wang Z, Levison BS, Buffa JA, Org E, Sheehy BT, Britt EB, Fu X, Wu Y, Li L, et al. Intestinal microbiota metabolism of L-carnitine, a nutrient in red meat, promotes atherosclerosis. Nature medicine. 2013;19(5):576–85.

Zhu W, Gregory JC, Org E, Buffa JA, Gupta N, Wang Z, Li L, Fu X, Wu Y, Mehrabian M, et al. Gut microbial metabolite TMAO ehances platelet hyperreactivity and thrombosis risk. Cell. 2016;165(1):111–24.

Koren O, Spor A, Felin J, Fak F, Stombaugh J, Tremaroli V, Behre CJ, Knight R, Fagerberg B, Ley RE, et al. Human oral, gut, and plaque microbiota in patients with atherosclerosis. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 2011;108(Suppl 1):4592–8.

Tang WH, Wang Z, Levison BS, Koeth RA, Britt EB, Fu X, Wu Y, Hazen SL. Intestinal microbial metabolism of phosphatidylcholine and cardiovascular risk. The New England journal of medicine. 2013;368(17):1575–84.

Wang Z, Roberts AB, Buffa JA, Levison BS, Zhu W, Org E, Gu X, Huang Y, Zamanian-Daryoush M, Culley MK, et al. Non-lethal Inhibition of gut microbial trimethylamine production for the treatment of atherosclerosis. Cell. 2015;163(7):1585–95.

Jie Z, Xia H, Zhong SL, Feng Q, Li S, Liang S, Zhong H, Liu Z, Gao Y, Zhao H, et al. The gut microbiome in atherosclerotic cardiovascular disease. Nature communications. 2017;8(1):845.

Olson CA, Vuong HE, Yano JM, Liang QY, Nusbaum DJ, Hsiao EY. The gut microbiota mediates the anti-seizure effects of the ketogenic diet. Cell. 2018;173(7):1728–1741 e1713.

Kelder T, Stroeve JH, Bijlsma S, Radonjic M, Roeselers G. Correlation network analysis reveals relationships between diet-induced changes in human gut microbiota and metabolic health. Nutrition & diabetes. 2014;4:e122.

He K, Hu Y, Ma H, Zou Z, Xiao Y, Yang Y, Feng M, Li X, Ye X. Rhizoma Coptidis alkaloids alleviate hyperlipidemia in B6 mice by modulating gut microbiota and bile acid pathways. Biochimica et biophysica acta. 2016;1862(9):1696–709.

Bourassa MW, Alim I, Bultman SJ, Ratan RR. Butyrate, neuroepigenetics and the gut microbiome: can a high fiber diet improve brain health? Neuroscience letters. 2016;625:56–63.

Topping DL, Clifton PM. Short-chain fatty acids and human colonic function: roles of resistant starch and nonstarch polysaccharides. Physiological reviews. 2001;81(3):1031–64.

Haghikia A, Jorg S, Duscha A, Berg J, Manzel A, Waschbisch A, Hammer A, Lee DH, May C, Wilck N, et al. Dietary fatty acids directly impact central nervous system autoimmunity via the small intestine. Immunity. 2016;44(4):951–3.

Schirmer M, Smeekens SP, Vlamakis H, Jaeger M, Oosting M, Franzosa EA, Ter Horst R, Jansen T, Jacobs L, Bonder MJ, et al. Linking the human gut microbiome to inflammatory cytokine production capacity. Cell. 2016;167(4):1125–1136 e1128.

Duncan SH, Holtrop G, Lobley GE, Calder AG, Stewart CS, Flint HJ. Contribution of acetate to butyrate formation by human faecal bacteria. The British journal of nutrition. 2004;91(6):915–23.

Tan J, McKenzie C, Potamitis M, Thorburn AN, Mackay CR, Macia L. The role of short-chain fatty acids in health and disease. Advances in immunology. 2014;121:91–119.

Macfarlane S, Macfarlane GT. Regulation of short-chain fatty acid production. The Proceedings of the Nutrition Society. 2003;62(1):67–72.

Maslowski KM, Vieira AT, Ng A, Kranich J, Sierro F, Yu D, Schilter HC, Rolph MS, Mackay F, Artis D, et al. Regulation of inflammatory responses by gut microbiota and chemoattractant receptor GPR43. Nature. 2009;461(7268):1282–6.

Kasubuchi M, Hasegawa S, Hiramatsu T, Ichimura A, Kimura I. Dietary gut microbial metabolites, short-chain fatty acids, and host metabolic regulation. Nutrients. 2015;7(4):2839–49.

Krautkramer KA, Kreznar JH, Romano KA, Vivas EI, Barrett-Wilt GA, Rabaglia ME, Keller MP, Attie AD, Rey FE, Denu JM. Diet-microbiota interactions mediate global epigenetic programming in multiple host tissues. Molecular cell. 2016;64(5):982–92.

Rothhammer V, Borucki DM, Tjon EC, Takenaka MC, Chao CC, Ardura-Fabregat A, de Lima KA, Gutierrez-Vazquez C, Hewson P, Staszewski O, et al. Microglial control of astrocytes in response to microbial metabolites. Nature. 2018;557(7707):724–8.