Abstract

Background

Previous narrative reviews have concluded that dietary nitrate (NO3−) improves maximal neuromuscular power in humans. This conclusion, however, was based on a limited number of studies, and no attempt has been made to quantify the exact magnitude of this beneficial effect. Such information would help ensure adequate statistical power in future studies and could help place the effects of dietary NO3− on various aspects of exercise performance (i.e., endurance vs. strength vs. power) in better context. We therefore undertook a systematic review and individual participant data meta-analysis to quantify the effects of NO3− supplementation on human muscle power.

Methods

The literature was searched using a strategy developed by a health sciences librarian. Data sources included Medline Ovid, Embase, SPORTDiscus, Scopus, Clinicaltrials.gov, and Google Scholar. Studies were included if they used a randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled, crossover experimental design to measure the effects of dietary NO3− on maximal power during exercise in the non-fatigued state and the within-subject correlation could be determined from data in the published manuscript or obtained from the authors.

Results

Nineteen studies of a total of 268 participants (218 men, 50 women) met the criteria for inclusion. The overall effect size (ES; Hedge’s g) calculated using a fixed effects model was 0.42 (95% confidence interval (CI) 0.29, 0.56; p = 6.310 × 10− 11). There was limited heterogeneity between studies (i.e., I2 = 22.79%, H2 = 1.30, p = 0.3460). The ES estimated using a random effects model was therefore similar (i.e., 0.45, 95% CI 0.30, 0.61; p = 1.064 × 10− 9). Sub-group analyses revealed no significant differences due to subject age, sex, or test modality (i.e., small vs. large muscle mass exercise). However, the ES in studies using an acute dose (i.e., 0.54, 95% CI 0.37, 0.71; p = 6.774 × 10− 12) was greater (p = 0.0211) than in studies using a multiple dose regimen (i.e., 0.22, 95% CI 0.01, 0.43; p = 0.003630).

Conclusions

Acute or chronic dietary NO3− intake significantly increases maximal muscle power in humans. The magnitude of this effect–on average, ~ 5%–is likely to be of considerable practical and clinical importance.

Similar content being viewed by others

Background

In 2007, Larsen et al. [1] reported that the ingestion of dietary nitrate (NO3−) reduced the oxygen (O2) cost of submaximal cycle ergometer exercise. Since then, over 100 studies have investigated the effects of this intervention (usually in the form of concentrated beetroot juice (BRJ)) on physiological responses and performance during endurance activities. Based on such research, recent systematic reviews and meta-analyses have concluded that dietary NO3− supplementation exerts a small-to-moderate ergogenic effect on endurance performance, at least in non-athletes and during open-ended, time-to-fatigue exercise tests [2,3,4,5,6,7]. The mechanism responsible for this improvement is still unclear, but it is presumably the result of the reduction of NO3− to nitrite (NO2−) and then to nitric oxide (NO) via bacterial or mammalian nitroreductases [8]. The resultant increase in NO bioavailability then decreases O2 demand and enhances performance during sustained exercise, seemingly by improving mitochondrial coupling [9] and/or by reducing ATP turnover itself [10]. Other studies, however, have failed to find any effects of NO3− supplementation on mitochondrial function in either mice [11] or humans [11, 12], leaving a decrease in ATP utilization, possibly at the cross-bridge level, as a more plausible mechanism. It should also be noted that the beneficial effects of NO3− ingestion on performance seem to be much smaller to insignificant in endurance athletes and/or during time trial type efforts [2,3,4,5,6,7].

More recently, attention has shifted to the effects of dietary NO3− supplementation on performance during strength- or sprint-type activities, i.e., during brief skeletal muscle activity wherein aerobic ATP production is minimal. As recently reviewed by Alvares et al. [13], dietary NO3− supplementation seems to have only a trivial impact on maximal force output during isometric or low velocity isotonic or isokinetic muscle contractions, although it may enhance the number of such repetitions that can be completed before failure [13, 14]. Animal studies, however, have demonstrated that the primary effects of NO on the contractile properties of muscle are not on force but on speed, i.e., on the maximal velocity of shortening, and hence on maximal muscle power, i.e., the product of force and speed [15, 16]. Consistent with this concept, a prior narrative review in 2018 concluded that acute dietary NO3− increases maximal muscular power in humans [17]. The potential for dietary NO3− to improve neuromuscular power is highly relevant to both athletic and patient populations alike, as power is typically more important than strength in determining either performance in sports [18, 19] or the ability to perform normal activities of daily living (e.g., standing up from a chair, climbing stairs) [20, 21]. The conclusions of this review, however, were based on roughly a dozen studies, and a number of pertinent investigations have since been published. Furthermore, no previous attempt has been made to employ meta-analysis to quantitatively assess the effects of dietary NO3− supplementation specifically on maximal muscle power in humans. Such information would be useful for ensuring adequate statistical power in future studies of this treatment and may help place the effects of dietary NO3− on various aspects of exercise performance (i.e., endurance vs. strength vs. power) in better context relative to each other.

To date, nearly all studies evaluating the effects of dietary NO3− on either aerobic or non-aerobic exercise performance have relied upon a crossover experimental design, in which each individual serves as their own control. This is widely considered to be the “gold standard” for evaluating the effects of interventions with a short time-course of action (e.g., dietary NO3−), as it minimizes random variability in treatment effects and thereby increases statistical power [22]. Yet, prior meta-analyses of the effects of dietary NO3− on exercise performance have either treated such within-subject data as a between-subject comparison [2,3,4,5,6,7, 23] or have assumed a relatively low, fixed within-subject correlation (i.e., r = 0.5) between the placebo and NO3− trials [13]. Although common, these approaches are widely known to potentially distort the results of meta-analyses and possibly lead to false conclusions [24,25,26,27]. This is partially because “Failure to account for correlation is likely to underestimate the precision of a study, that is, to give it confidence intervals that are too wide and a weight that is too small” [27]. Meta-analyses based on aggregate (i.e., group mean) data are also susceptible to other sources of error, e.g., ecological bias [25].

Accordingly, we performed a systematic review and meta-analysis of the literature to determine the effects of ingesting dietary NO3− on maximal muscle power in humans, as assessed using a randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled, crossover experimental design. To account for the typically very high within-subject reproducibility of tests of human neuromuscular power (e.g., r = 0.99 [28];), we based our meta-analysis on the responses of individual subjects to NO3− vs. placebo, as opposed to using aggregate data.

Methods

The protocol for this study was registered at the International Prospective Register of Systematic Reviews (PROSPERO) and can be accessed at www.crd.york.ac.uk/PROSPERO/display_record.asp?ID=CRD42021238851. Conduct and reporting of the study was performed based on published guidelines [25, 27, 29, 30].

Information sources

We conducted a systematic search of the following databases from their inception until May 4, 2021: Medline (Ovid), EMBASE (Embase.com), SportDiscus (EBSCO), Scopus (Scopus.com), Clinicaltrials.gov, and Google Scholar. For Google Scholar, all articles (excluding books) were retrieved from the first five pages. We did not restrict the search by language or publication date. Abstracts as well as full publications were included to minimize the potential for publication bias [31].

Search strategy

The database search strategies were developed by a health sciences librarian (RJH) with expertise in literature searches. Known, relevant articles collected by the authors were analyzed to select keywords and subject headings. An initial search strategy in Medline Ovid was then iteratively developed by adding and removing additional keywords and subject headings until all known, relevant articles were retrieved by the search, and no new, relevant articles were found. The final search terms incorporated subject headings and keywords associated with dietary NO3− and skeletal muscle power. The full search strategies for all information sources are provided in Supplemental Table 1.

The above automated searches were supplemented by a manual search of the literature, relying on the authors’ knowledge of existing publications, consultation of reference lists, etc. This searching turned up two additional publications.

Inclusion and exclusion criteria

Studies were included if they 1) utilized a randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled, crossover experimental design, 2) measured the effects of dietary NO3− supplementation on peak or maximal neuromuscular power (in either watts or watts/kg body mass) performed with either a small or large muscle mass in the non-fatigued state (i.e., no immediately-prior exercise trials) in a normoxic, temperate environment, and 3) the within-subject correlation could be determined from data in the published manuscript or obtained from the authors. Studies not meeting these criteria (e.g., [32,33,34,35,36,37,38,39,40]) were excluded. For example, the studies of Corry and Gee [36] and Tatlichi and Çakmakçi [38] were excluded because they were not double-blind, whereas that of Williams et al. [39] was excluded because power was measured at 70% of one repetition-maximum (1 RM), which is far removed from the optimal resistance of < 30% of 1 RM for determination of peak or maximal muscle power [41]. The studies of Kokkinoplitis and Chester [35] and Conger, Zamzow, and Darnell [40] were excluded because we were unable to obtain the required data from the authors. The implications of excluding these two studies are considered in the Discussion.

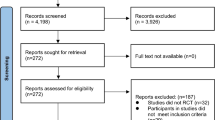

The Preferred Reporting of Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA) flow diagram is shown in Fig. 1.

Study selection and data extraction

All records were imported into Covidence software (Veritas Health Innovation) for de-duplication and screening. Screening was completed in two parts. First, titles and abstracts were independently screened by two authors (ARC and SJC) to determine their eligibility. Any disagreements were resolved in consultation with a third author (MNB). Second, full-text articles were screened using the same process. Data extraction was then independently performed by the same three authors. Specifically, study design, sample size, subject characteristics, form, dose, and duration of NO3− supplementation, placebo characteristics, experimental procedures, and testing conditions were obtained from the text of eligible papers [42,43,44,45,46,47,48,49,50,51,52,53,54,55,56,57,58,59,60]. Effect sizes (ES), i.e., Hedge’s g, for NO3−-induced changes in peak or maximal power were calculated from either 1) the means and SDs for the NO3− and placebo trials along with the exact P values for the within-subject comparison [49, 53, 55, 58, 60], or 2) anonymized individual subject data obtained from the authors [42,43,44,45,46,47,48, 50,51,52, 54, 56, 57, 59]. Since data from the 12 subjects in our original study [43] were also included in a subsequent report [50], only the results from the eight additional subjects in the latter study were used in the meta-analysis. A number of the studies employed a repeated sprint cycling protocol and/or only reported the mean power during a Wingate-style test [51, 52, 54, 55, 60]. In such instances, peak power from the first sprint was obtained from the authors and utilized in the meta-analysis. Since Jonvik et al. [52] found no difference between recreational, national caliber, and Olympic level speedskaters in the response to dietary NO3−, data from this study were treated as arising from a single pool of subjects. To avoid possible confounding effects from varying environmental conditions, only the data from the temperate trial in the study by Smith et al. [54] were used. For the study of Rodríguez-Fernández et al. [58], in which subjects performed concentric and eccentric squat exercises against varying inertial loads, the concentric peak power at the lowest load was used. Plotting of peak power against inertial load demonstrated that this resistance was close to optimal for determination of maximal muscle power. Finally, since we have recently shown that there is no beneficial effect of dietary NO3− on muscle power at very high doses (i.e., 400 μmol/kg, or on average 27.4 mmol) [59], only the data from the low dose (i.e., 200 μmol/kg, or 13.7 mmol) trial of this study were used. (Why the beneficial effect of dietary NO3− on muscle contractile function is diminished or even completely lost at very high doses is unclear. We have hypothesized, however, that it may be due to competition between NO3− and NO2− for reduction by xanthine oxidoreductase [61].)

Quality assessment

Although numerous tools exist for judging the quality of randomized trials, most lack evidence of reliability and validity [30]. Based on the information extracted from each publication as described above, the quality of the studies was therefore judged against 13 elements of experimental design and execution held to be important in the context of the research question of interest [30]. Where uncertainties existed, authors were contacted for further clarification. Studies were classified as being of low (i.e., ≤8), moderate (i.e., 9–11), or high (i.e., ≥12) quality based on the presence or absence of these elements. The complete results of this quality assessment are included in Supplemental Table 2.

Statistical analyses

For each individual study, Hedge’s g with small sample bias correction was calculated from the individual mean difference di, the corresponding standard deviation SDi, and the sample size Ni as [62]:

Its variance (var(gi)) was calculated as

where δ is the simple arithmetic mean of gi [63]. The 95% confidence interval (CI) was obtained from the method of noncentral t distributions [64]. Both fixed-effects meta-analyses and random-effects meta-analyses were performed, with the primary ones used for interpretations decided based on the between-study heterogeneity evaluations. Heterogeneity between studies was evaluated by I2, H2, and the corresponding p-value. Funnel plot and Egger’s test were used to evaluate potential publication biases. Meta-regressions were used to assess the effects of a factor on the combined effect size. Given the limited study number, simple meta-regressions were used. Subgroup analyses were generated when needed. The 95% CIs of Hedge’s g and the forest and funnel plot were generated with Matlab R2020b (Mathworks, Natick, MA, USA). The meta-analyses were performed with R package metafor version 2.4–0 [62]. Two-sided p-values < 0.05 were considered statistically significant.

Results

Characteristics of included studies

We were able to identify and obtain data from 19 investigations that included a total of 268 subjects (218 men, 50 women). Selected characteristics of these studies are shown in Table 1. The dose of NO3− used ranged from 6.4 (estimated) to 15.9 (measured) mmol, almost always (i.e., 17/19 studies) in the form of concentrated BRJ usually (i.e., 14/19 studies) given as an acute dose. The majority (i.e., 16/19) of the studies were judged to be of at least moderate quality, on average satisfying 11 ± 2 (SD) out of 13 of our pre-established criteria (including use of a randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled, crossover design). The most common weaknesses identified were 1) failure to measure the actual dose of NO3− administered (11/19) and 2) failure to measure any markers of resulting changes in NO3− bioavailability (i.e., plasma NO3− and NO2−, breath NO) (10/19). Several of the studies also used colored and flavored water instead of NO3−-depleted BRJ as a placebo, which was judged to inferior to the nitrate-depleted BRJ beverage used in the majority of studies (13/19).

Overall effect size

Although the magnitude varied somewhat and did not always achieve statistical significance, a positive effect of dietary NO3− on muscle power was observed in 19/19 studies (Fig. 1). The overall ES as estimated using a fixed effects model was 0.42 (95% confidence interval (CI) 0.29, 0.56; p = 6.310 × 10− 11). There was limited heterogeneity between studies (i.e., I2 = 22.79%, H2 = 1.30, p = 0.3460). As a result, the ES estimated using a random effects model was similar (i.e., 0.45, 95% CI 0.30, 0.61; p = 1.064 × 10− 9; Fig. 2).

Forest plot of effect sizes (i.e., Hedge’s g) for all 19 studies of the effects of dietary NO3− supplementation on maximal muscle power included in the meta-analysis. The size of each symbol is proportional to the weighting of each study, with the horizontal error bar representing the 95% confidence interval (CI). The horizontal diamonds at the bottom of the figure illustrate the overall effect size plus or minus the 95% CI as determined using fixed or random effects models

Evaluation for publication bias/small study effects

The funnel plot is shown in Fig. 3. Egger’s regression test for funnel plot asymmetry was not significant (p = 0.0780), arguing against any major publication bias/small study effects.

Results of sub-group analyses

Exploratory sub-group analyses and meta-regressions were performed to evaluate the influence of subject age, sex, test modality (i.e., small versus large muscle mass exercise), and dietary NO3− dosing regimen (i.e., acute dose vs. 5–6 d of treatment) on the ES. The effects of age, sex, and test modality were not significant (i.e., p = 0.1952, 0.9488, and 0.5328, respectively). In contrast, the ES from studies employing an acute NO3− dose as estimated using a fixed effects model (i.e., 0.54, 95% CI 0.37, 0.71; p = 6.774 × 10− 12; Fig. 4) was 0.32 ± 0.14 greater (p = 0.0211) than that found in studies using a multi-day dosing regimen (i.e., 0.22, 95% CI 0.01, 0.43; p = 0.003630; Fig. 5). There was very little heterogeneity in either sub-grouping (i.e., I2 = 0.00%, H2 = 1.00, p = 0.6480 for acute dose studies and I2 = 12.26%, H2 = 1.14, p = 0.4211 for multiple dose studies). Nearly identical results were therefore obtained using a random effects model (Figs. 4 and 5).

Forest plot of effect sizes (i.e., Hedge’s g) for the 14 studies of the effects of acute dietary NO3− supplementation on maximal muscle power. See legend to Fig. 2 for additional details

Forest plot of effect sizes (i.e., Hedge’s g) for the 5 studies of the effects of 5–6 d of dietary NO3− supplementation on maximal muscle power. See legend to Fig. 2 for additional details

Discussion

This is the first systematic review and meta-analysis evaluating the effects of dietary NO3− supplementation on maximal neuromuscular power in humans, and also the first individual participant data meta-analysis of the effects of dietary NO3− on any aspect of human performance. Our primary finding is that NO3− intake significantly enhances muscle power, thus supporting the conclusions of previous narrative reviews [14, 17]. This effect was statistically independent of subject age or sex and was evident during both small and large muscle mass exercise. Somewhat unexpectedly, however, the ES was greater in studies using an acute dose of NO3− versus a multi-day supplementation protocol, although the latter was still significant.

As discussed by Riley et al. [25], performing meta-analysis using individual participant data provides numerous advantages, including the ability to account for within-subject correlation of results and the opportunity to perform subgroup analyses that may not be possible when using aggregate data. The former increases the power to detect treatment effects and is especially relevant in the present context, in which the average within-subject correlation of power during the placebo and NO3− trials was 0.94 (range 0.73–0.99). Taking the latter into consideration, we found an overall ES of 0.43 (0.45 using a random effects model), which is substantially larger than those previously calculated from aggregate data for the effects of dietary NO3− on either endurance time trial performance (i.e., ES = 0.05–0.12; 2–7) or on strength (i.e., ES = 0.08; 12). More importantly, however, an ES of this magnitude–which equates to a ~ 5% increase in maximal muscle power–is likely to be of considerable athletic and clinical significance, as previously discussed [43, 44, 56]. For example, it has been estimated that a mere 1% improvement in performance can double the odds of victory for an elite athlete [65]; in this context a 5% increase is enormous. Similarly, based on data from de Moura et al. [66] a 5% increase in maximal knee extensor power would be expected to reduce the odds of limitations in dynamic balance, habitual gait speed, or chair stand performance in inactive elderly subjects by roughly one-third. Thus, it is clear that dietary NO3− holds considerable potential as a means of enhancing muscular power in both athletic and patient populations alike.

Some previous meta-analyses of the effects of dietary NO3− on exercise performance have indiscriminately pooled data from studies utilizing disparate exercise tasks with markedly different physiological demands [4,5,6,7]. In contrast, we focused specifically on the novel outcome of maximal neuromuscular power. Perhaps as a result, we found only limited heterogeneity across studies. Nevertheless, we performed exploratory sub-group analyses to identify potential factors that might impact the ES. As stated above, subject age did not have a significant effect, which is in keeping with our prior small correlational study of 20 subjects [50]. Similarly, subject sex did not have a significant influence. This contrasts with the results of our previous investigation [50], in which the women (n = 7) appeared more likely to benefit from NO3− supplementation. However, it also differs from the recent meta-analysis by Senefeld et al. [6], who concluded based on aggregate data (in which only 5% of studies were exclusively of women) that NO3− supplementation does not enhance exercise performance in women. The reason for this apparent discrepancy is not known, but it may reflect the much larger number of women (and men) represented in the present meta-analysis. Finally, no difference was found between studies using small versus large muscle mass exercise (e.g., knee extension vs. cycling), a finding which parallels our previous work (e.g., 43 vs 45). Together, these findings support the robust nature of the effect of dietary NO3− on human muscle power.

In contrast to the lack of effect of age, sex, and muscle mass, the dietary NO3− dosing regimen used may have an impact. Specifically, studies using a multi-day supplementation protocol exhibited a lower (but still significant) ES compared to studies employing an acute dose of NO3−. One possible explanation for this finding is that repeated dosing exceeds the optimal NO3− concentration for enhancing contractile function in skeletal muscle [59]. However, pharmacokinetic modeling of the combined NO3−/NO2− system indicates that there should be little further accumulation in tissue after the first couple of doses [67]. Furthermore, prior meta-analyses of the effects of dietary NO3− on endurance exercise performance have revealed no differences between acute and chronic dosing regimens [3,4,5,6]. Thus, additional research is required to determine whether the acute NO3−-induced improvement in muscle power is in fact diminished with repeated dosing, especially in patient populations who might benefit from NO3− supplementation during activities of daily living (vs. athletes who might ingest NO3− only prior to competitions).

As is true with endurance exercise [3, 5, 6], other potential modulators of the effects of dietary NO3− on muscle power include the actual dose of NO3− ingested [59] and/or the plasma levels of NO3− and/or NO2− attained following NO3− ingestion [50]. We did not attempt to assess these factors in the present meta-analysis, however, because less than half of the included studies directly measured either of these parameters, and aside from our studies [43, 44, 50, 56, 59] only Wylie et al. [48] and Jonvik et al. [57] measured both. This is a significant weakness of the current literature in this area, as we have found the NO3− content of various BRJ supplements commonly used in such studies can vary considerably [68], even when obtained from the same manufacturer. Furthermore, we have found that the NO3− content of various BRJ products decreases gradually over time (unpublished observations). Future studies should therefore explicitly document the precise dose of NO3− provided as well as quantify the impact this has on biomarkers of NO bioavailability.

Based on previous research of the effects of NO3− supplementation on endurance exercise performance [2, 4,5,6], another potential modulator of the ES among subjects is their training status or level of physical activity. We did not formally attempt to assess this possible influence, due in part to the difficulty of objectively classifying subjects in the various studies, many of whom were simply described as being “recreationally active”. As previously noted, however, we found only limited statistical heterogeneity across investigations, even though the subjects ranged from patients with heart failure [44] to healthy older individuals [56, 59] to Olympic-level athletes [52]. This argues against subject population having a major impact on the magnitude of the dietary NO3−-induced increase in muscle power. Nonetheless, it is interesting to note that two of the three studies exhibiting the smallest ES (i.e., [52, 60]) tested highly trained sprinters. Additional research is therefore warranted to determine whether regular sprint training attenuates the positive effects of NO3− supplementation on maximal power.

Regrettably, we were unable to obtain the data required to include additional studies by Kokkinoplitis and Chester [35] and Conger, Zamzow, and Darnell [40] in our meta-analysis. However, conservatively assuming the same within-subject correlation as the lowest found in the included studies (i.e., 0.73), the ES in the n = 7 subjects studied by Kokkinoplitis and Chester [35] would have been 0.36 (95% CI -0.33, 1.02), which is similar to that calculated from the data in the present meta-analysis. Applying the same logic to the results from the n = 14 subjects studied by Conger, Zamzow, and Darnell [40] extracted from their Fig. 1a yields a lower ES, i.e., 0.13 (95% CI -0.37, 0.62). This may be because these authors used a BRJ powder that we have found to contain very little NO3− [68]. Regardless, even if the individual subject data had been available the inclusion of either or both of these two additional studies would have been unlikely to have appreciably changed our results, which are based on 19 other studies of a total of 268 subjects.

Although the results of the present meta-analysis clearly demonstrate that dietary NO3− increases muscle power in humans, the mechanism responsible for this effect still remains to be established. We have previously hypothesized that it may be due to greater NO-stimulated production of cyclic guanosine monophosphate (cGMP), leading to increased myofibrillar Ca2+ sensitivity as a result of enhanced phosphorylation of the myosin regulatory light chain (RLC) [17]. Recently, though, Kumar et al. [69] reported that NO3− supplementation did not increase RLC phosphorylation in the diaphragm of aged mice, even though it did increase peak power. As discussed previously [17], there are notable differences between rodents and humans in dietary NO3−/NO2−/NO metabolism, making the relevance of these findings unclear. It is also possible that dietary NO3− increases Ca2+ sensitivity and hence muscle power via a non-cGMP-dependent mechanism, e.g., increased nitros(yl)ation of the ryanodine receptor [17]. As such, the biochemical mechanism by which NO3− intake improves human muscle power therefore requires additional study.

Conclusions

The present meta-analysis lends quantitative support to previous narrative reviews [14, 17] that have concluded that NO3− supplementation enhances maximal neuromuscular power in humans. Based on the currently available literature, this ergogenic effect is seemingly independent of subject age, sex, or the amount of muscle mass engaged in the activity but may be greater with acute vs. repeated dosing. Importantly, this dietary NO3−-induced increase in power is sufficient to have important practical and clinical implications. Further research to determine the optimal supplementation regimen, target population, etc., is therefore imperative.

Availability of data and materials

The datasets used and/or analyzed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

Abbreviations

- 1 RM:

-

One repetition maximum

- BRJ:

-

Beetroot juice

- KNO3 - :

-

Potassium nitrate

- NO:

-

Nitric oxide

- NO2 - :

-

Nitrite

- NO3 - :

-

Nitrate

- O2 :

-

Oxygen

- PRISMA:

-

Preferred Reporting of Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses

References

Larsen FJ, Weitzberg E, Lundberg JO, Ekblom B. Effects of dietary nitrate on oxygen costs during exercise. Acta Physiol. 2007;191(1):59–66. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1748-1716.2007.01713.x.

Hoon MW, Johnson NA, Chapman PG, Burke LM. The effect of nitrate supplementation on exercise performance in healthy individuals. Int J Sport Nutr Exerc Metab. 2013;23(5):522–32. https://doi.org/10.1123/ijsnem.23.5.522.

McMahon NF, Leveritt MD, Pavey TG. The effect of dietary nitrate supplementation on endurance exercise performance in healthy adults: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Sports Med. 2017;47(4):735–56. https://doi.org/10.1007/s40279-016-0617-7.

Campos HO, Drummond LR, Rodriques QT, Machado FSM, Pires W, Wanner SP, et al. Nitrate supplementation improves physical performance specifically in non-athletes during prolonged open-ended tests: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Br J Nutr. 2018;119(6):636–57. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0007114518000132.

Van De Walle GP, Vokovich MD. The effect of nitrate supplementation on exercise tolerance and performance: a systematic review and meta-analysis. J Strength Cond Res. 2018;32(6):1796–808. https://doi.org/10.1519/JSC.0000000000002046.

Senefeld JW, Wiggins CC, Regimbal RJ, Dominelli PB, Baker SE, Joyner MJ. Ergogenic effect of nitrate supplementation: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Med Sci Sports Exerc. 2020;52:22502261. https://doi.org/10.1249/MSS.0000000000002363.

Gao C, Gupta S, Adli T, Hou W, Coolsaet R, Hayes A, et al. The effect of dietary nitrate supplementation on endurance exercise performance and cardiorespiratory measures in healthy adults: a systematic review and meta-analysis. J Int Soc Sports Nutr. 2021;18(1):55. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12970-021-00450-4.

Lundberg JO, Weitzberg E, Gladwin MT. The nitrate-nitrite-nitric oxide pathway in physiology and therapeutics. Nat Rev Drug Discov. 2008;7(2):156–67. https://doi.org/10.1038/nrd2466.

Larsen FJ, Schiffer TA, Borniquel S, Sahlin K, Ekblom B, Lundberg JO, et al. Dietary inorganic nitrate improves mitochondrial efficiency in humans. Cell Metab. 2011;13(2):149–59. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cmet.2011.01.004.

Bailey SJ, Fulford J, Vanhatalo A, Winyard PG, Blackwell JR, DiMenna FJ, et al. Dietary nitrate supplementation enhances muscle contractile efficiency during knee-extensor exercise in humans. J Appl Physiol. 2010;109(1):135–48. https://doi.org/10.1152/japplphysiol.00046.2010.

Ntessalen M, Procter NEK, Schwarz K, Loudon BL, Minnion M, Fernandez BO, et al. Inorganic nitrate and nitrite supplementation fails to improve skeletal muscle mitochondrial efficiency in mice and humans. Am J Clin Nutr. 2020;111(1):79–89. https://doi.org/10.1093/ajcn/nqz245.

Whitfield J, Ludzki A, Heigenhauser GJ, Senden JM, Verdijk LB, van Loon LJ, et al. Beetroot juice supplementation reduces whole body oxygen consumption but does not improve indices of mitochondrial efficiency in human skeletal muscle. J Physiol. 2016;594(2):421–35. https://doi.org/10.1113/JP270844.

Alvares TS, de Oliveira GV, Volino-Souza M, Contes-Junior CA, Murias JM. Effects of dietary nitrate ingestion on muscular performance: a systematic review and meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. Crit Rev Food Sci Nutr. 2021:1–23. https://doi.org/10.1080/10408398.2021.1884040.

San Juan AF, Dominguez R, Lago-Rodriguez A, Montoya JJ, Tan R, Bailey SJ. Effects of dietary nitrate supplementation on weightlifting exercise performance in healthy adults: a systematic review. Nutrients. 2020;12(8). https://doi.org/10.3390/nu12082227.

Maréchal G, Gailly P. Nitric oxide and skeletal muscle contraction. Cell Mol Life Sci. 1999;55(9):1088–102. https://doi.org/10.1007/s000180050359.

Stamler JS, Meissner G. Physiology of nitric oxide in skeletal muscle. Physiol Rev. 2001;81(1):209–37. https://doi.org/10.1152/physrev.2001.81.1.209.

Coggan AR, Peterson LR. Dietary nitrate influences the contractile properties of human muscle. Exerc Sport Sci Rev. 2018;46(4):254–61. https://doi.org/10.1249/JES.0000000000000167.

Baker D. Comparison of upper-body strength and power between professional and college-aged rugby league players. J Strength Cond Res. 2001;15(1):30–5.

Sleivert G, Taingahue M. The relationship between maximal jump-squat power and sprint acceleration in athletes. Eur J Appl Physiol. 2004;91(1):46–52. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00421-003-0941-0.

Pojednic RM, Clark DJ, Patten C, Reid K, Phillips EM, Fielding RA. The specific contribution of force and velocity to muscle power in older adults. Exp Gerontol. 2012;47(8):608–12. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.exger.2012.05.010.

Reid KF, Fielding RA. Skeletal muscle power: a critical determinant of physical functioning in older adults. Exerc Sports Sci Rev. 2012;40(1):4–40. https://doi.org/10.1097/JES.0b013e31823b5f13.

U.S. Food and Drug Administration, Centers for Drug Evaluation and Research and Biologics Evaluation and Research. Clinical pharmacology data to support a demonstration of biosimilarity to a reference product. 2016. https://www.fda.gov/regulatory-information/search-fda-guidance-documents/clinical-pharmacology-data-support-demonstration-biosimilarity-reference-product. Accessed 1 June 2021.

Lago-Rodríguez A, Domínguez R, Ramos-Álvarez JJ, Tobal FM, Jodra P, Tan R, et al. The effect of dietary nitrate supplementation on isokinetic torque in adults: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Nutrients. 2020;12(10). https://doi.org/10.3390/nu12103022.

Stewart LA, Parmar MKB. Meta-analysis of the literature or of individual patient data: is there a difference? Lancet. 1993;341(8842):418–22. https://doi.org/10.1016/0140-6736(93)93004-K.

Riley RD, Lambert PC, Abo-Zaid G. Meta-analysis of individual participant data: rationale, conduct, and reporting. BMJ. 2010;340(feb05 1):c221. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmj.c221.

Tierney JF, Fisher DJ, Burdett S, Stewart LA, Parmer MKB. Comparison of aggregate and individual participant data approaches to meta-analysis of randomised trials: an observational study. PLoS Med. 2020;17(1):e1003019. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pmed.1003019.

Higgins J, Thomas J, Chandler J, Cumpston M, Li T, Page MJ, Welch VA. Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions Version 6.2. 2021. https://training.cochrane.org/handbook/current Accessed 21 May 2021.

Martin JC, Wagner BM, Coyle EF. Inertial-load method determines maximal cycling power in a single exercise bout. Med Sci Sports Exerc. 1997;29(11):1505–12. https://doi.org/10.1097/00005768-199711000-00018.

Stewart LA, Clarke M, Rovers M, Riley RD, Simmonds M, Stewart G, et al. PRISMA-IPD development group. Preferred reporting items for a systematic review and meta-analysis of individual participant data: the PRISMA-IPD statement. JAMA. 2015;313(16):1657–65. https://doi.org/10.1001/jama.2015.3656.

Rao G, Lopez-Jimenez F, Boyd J, D’Amico F, Durant NH, Hlatky MA, et al. Methodological standards for meta-analyses and qualitative systematic reviews of cardiac prevention and treatment studies: a scientific statement from the American Heart Association. Circulation. 2017;136:e172–94.

Scherer RW, Saldanha IJ. How should systematic reviewers handle conference abstracts? A view from the trenches. Syst Rev. 2019;8:264. https://doi.org/10.1186/s13643-019-1188-0.

Muggerridge DJ, Howe CCF, Spendiff O, Pedlar C, James PE, Easton C. The effects of a single dose of concentrated beetroot juice on performance in trained flatwater kayakers. Int J Sport Nutr Exerc Metab. 2013;23(5):498–506. https://doi.org/10.1123/ijsnem.23.5.498.

Martin K, Smee D, Thompson KG, Rattray B. No improvement in repeated-sprint performance with dietary nitrate. Int J Sports Physiol Perf. 2014;9(5):845–50. https://doi.org/10.1123/ijspp.2013-0384.

Byrne G, Wardrop B, Storey A. The effect of beetroot juice dosage on high intensity intermittent cycling performance. J Sci Cycling. 2014;3:2.

Kokkinoplitis K, Chester N. The effect of beetroot juice on repeated sprint performance and muscle force production. J Phys Educ Sport. 2014;14:242–7.

Corry LR, Gee TI. Dietary nitrate enhances power output during the early phases of maximal intensity sprint cycling. Int J Coach Sci. 2015;9:87–97.

Kent GL, Dawson B, McNaughton LR, Cox GR, Burke LM, Peeling P. The effect of beetroot juice supplementation on repeat-sprint performance in hypoxia. J Sports Sci. 2019;37(3):339–46. https://doi.org/10.1080/02640414.2018.1504369.

Tatlichi A, Çakmakçi O. The effects of acute dietary nitrate supplementation on anaerobic power of elite boxers. Med Sport. 2019;72:225–33.

Williams TD, Martin MP, Mintz JA, Rogers RR, Ballman CG. Effect of acute beetroot juice supplementation on bench press power, velocity, and repetition volume. J Strength Cond Res. 2020;34(4):924–8. https://doi.org/10.1519/JSC.0000000000003509.

Conger SA, Zamzow CM, Darnell ME. Acute beet root supplementation does not improve 30- or 60-second maximal intensity performance in anaerobically trained athletes. Int J Exerc Sci. 2021;14(2):60–75.

Soriano MA, Suchomel TJ, Martin PJ. The optimal load for maximal power production during upper-body resistance exercises: a meta-analysis. Sports Med. 2017;47(4):757–68. https://doi.org/10.1007/s40279-016-0626-6.

Rothwell S, Alkhatib A. Effects of acute dietary nitrate supplementation on 30-second Wingate performance in healthy collegiate males. Br J Sports Med. 2014;48(Suppl 3):A11–A1A11. https://doi.org/10.1136/bjsports-2014-094245.31.

Coggan AR, Leibowitz JL, Kadkhodayan A, Thomas DT, Ramamurthy S, Anderson Spearie C, et al. Effect of acute dietary nitrate intake on knee extensor speed and power in healthy men and women. Nitric Oxide. 2015;48:16–21. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.niox.2014.08.014.

Coggan AR, Leibowitz JL, Anderson Spearie C, Kadkhodayan A, Thomas DP, Ramamurthy S, et al. Acute dietary nitrate intake improves muscle contractile function in patients with heart failure: a double-blind, placebo-controlled, randomized trial. Circ Heart Fail. 2015;8(5):914–20. https://doi.org/10.1161/CIRCHEARTFAILURE.115.002141.

Rimer EG, Peterson LR, Coggan AR, Martin JC. Acute dietary nitrate supplementation increases maximal cycling power in athletes. Int J Sports Physiol Perf. 2016;11(6):715–20. https://doi.org/10.1123/ijspp.2015-0533.

Porcelli S, Pugliese L, Rejc E, Pavei G, Bonato M, Montorsi M, et al. Effects of a short-term high-nitrate diet on exercise performance. Nutrients. 2016;8(9). https://doi.org/10.3390/nu8090534.

Kramer SJ, Baur DA, Spicer MT, Vukovich MD, Ormsbee MJ. The effect of six days of dietary nitrate supplementation on performance in trained CrossFit athletes. J Int Soc Sports Nutr. 2016;13(1):39. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12970-016-0150-y.

Wylie LJ, Bailey SJ, Kelly J, Blackwell JR, Vanhtatalo A, Jones AM. Influence of beetroot juice supplementation on intermittent exercise performance. Eur J Appl Physiol. 2016;116(2):415–25. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00421-015-3296-4.

Domínguez R, Garnacho-Castaño MV, Cuenca E, García-Fernández P, Muñoz-González A, de Jesús F, et al. Effects of beetroot juice supplementation on a 30-s high-intensity inertial cycle ergometer test. Nutrients. 2017;9(12). https://doi.org/10.3390/nu9121360.

Coggan AR, Broadstreet SR, Mikhalkova D, Bole I, Leibowitz JL, Kadkhodayan A, et al. Dietary nitrate-induced increases in human muscle power: high versus low responders. Physiol Rep. 2018;6(2):e13575. https://doi.org/10.14814/phy2.13575.

Bender D, Townsend JR, Vantrease WC, Marshall AC, Henry RN, Heffington SH, et al. Acute beetroot juice administration improves peak isometric force production in adolescent males. App Physiol Nutr Metab. 2018;43(8):816–21. https://doi.org/10.1139/apnm-2018-0050.

Jonvik KL, van Dijk JW, Masse K, Senden JM, van Loon LJ, et al. Repeated-sprint performance and plasma responses following beetroot juice supplementation do not differ between recreational, competitive, and elite sprint athletes. Eur J Sport Sci. 2018;7(4):1–10. https://doi.org/10.1080/17461391.2018.1433722.

Cuenca E, Jodra P, Pérez-Lopéz A, González-Rodríguez LG, da Silva SF, Veiga-Herreros P, et al. Effects of beetroot juice supplementation on performance and fatigue in a 30-s all-out sprint exercise: a randomized, double-blind, cross-over study. Nutrients. 2018;10(9). https://doi.org/10.3390/nu10091222.

Smith K, Muggeridge DJ, Easton C, Ross MD. An acute dose of inorganic nitrate does not improve high-intensity intermittent exercise performance in temperate or hot and humid conditions. Eur J Appl Physiol. 2019;119(3):723–33. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00421-018-04063-9.

Jodra P, Domínguez R, Sáncez-Oliver AJ, Veiga-Herreros P, Bailey SJ. Effect of beetroot juice supplementation on mood, perceived exertion, and performance during a 30-second Wingate test. Int J Sports Physiol Perf. 2020;15(2):243–8. https://doi.org/10.1123/ijspp.2019-0149.

Coggan AR, Hoffman RL, Gray DA, Moorthi RN, Thomas DP, Leibowitz JL, et al. A single dose dietary of nitrate increases maximal muscle speed and power in healthy older men and women. J Gerontol A Biol Sci Med Sci. 2020;75:1154–60.

Jonvik J, Hoogervorst D, Peelen HB, De Niet M, Verdijk LB, Van Loon LJC, et al. The impact of beetroot juice supplementation on muscle endurance, maximal strength, and countermovement jump performance. Eur J Sport Sci. 2020;21(6):871–8. https://doi.org/10.1080/17461391.2020.1788649.

Rodríguez-Fernández A, Castillo D, Raya-González J, Domínguez R, Bailey SJ. Beetroot juice supplementation increases concentric and eccentric muscle power output. Original investigation. J Sci Med Sport. 2021;24(1):80–4. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jsams.2020.05.018.

Gallardo EJ, Gray DA, Hoffman RL, Yates BA, Moorthi RN, Coggan AR. Dose-response effect of dietary nitrate on muscle contractility and blood pressure in older subjects: a pilot study. J Gerontol A Biol Sci Med Sci. 2021;76(4):591–8. https://doi.org/10.1093/gerona/glaa311.

Dumar AM, Huntington AF, Rogers RR, Kopec TJ, Williams TD, Ballmann CG. Acute beetroot juice supplementation attenuates morning-associated decrements in supramaximal exercise performance in trained sprinters. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2021;18(2):412. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph18020412.

Damacena-Angelis C, Oliveira-Paula GH, Pinheiro LC, Crevelin EJ, Portella RL, Moraes LAB, et al. Nitrate decreases xanthine oxidoreductase-mediated nitrite reductase activity and attenuates vascular and blood pressure responses to nitrite. Redox Biol. 2017;12:291–9. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.redox.2017.03.003.

Viechtbauer W. Conducting meta-analyses in R with the metafor package. JSS. 2010;36:1–48.

Morris SB, DeShon RP. Combining effect size estimates in meta-analysis with repeated measures and independent-groups designs. Psychol Methods. 2002;7(1):105–25. https://doi.org/10.1037/1082-989X.7.1.105.

Hedges LV. Distribution theory for glass’s estimator of effect size and related estimators. J Educ Stat. 1981;6(2):107–28. https://doi.org/10.3102/10769986006002107.

Hopkins WG, Hawley JA, Burke LM. Design and analysis of research on sport performance enhancement. Med Sci Sports Exerc. 1999;31(3):472–85. https://doi.org/10.1097/00005768-199903000-00018.

de Moura TG, de Almeida NC, Garcia PA. The influence of isokinetic peak torque and muscular power on the functional performance of active and inactive community dwelling elderly: a cross-sectional study. Braz J Phys Ther. 2020;24(3):256–63. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.bjpt.2019.03.003.

Coggan AR, Racette SB, Thies D, Peterson LR, Stratford RE Jr. Simultaneous pharmacokinetic analysis of nitrate and its reduced metabolite, nitrite, following ingestion of inorganic nitrate in a mixed patient population. Pharm Res. 2020;37(12):235. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11095-020-02959-w.

Gallardo EJ, Coggan AR. What’s in your beet juice? Nitrate and nitrite content of beet juice products marketed to athletes. Int J Sport Nutr Exerc Metab. 2019;29(4):345–9. https://doi.org/10.1123/ijsnem.2018-0223.

Kumar RA, Kelley RC, Hahn D, Ferreira LF. Dietary nitrate supplementation increases diaphragm peak power in old mice. J Physiol. 2020;598(19):4357–69. https://doi.org/10.1113/JP280027.

Acknowledgements

We sincerely thank the numerous investigators who readily responded to our requests for information such that the present study could be performed.

Funding

This work was funded in part by the Indiana Clinical and Translational Sciences Institute by grant number UL1TR002529 from the National Institutes of Health, National Center for Advancing Translational Sciences, Clinical and Translational Sciences Award and by grant number AG053606 from the National Institute on Aging. The contents of this article are solely the responsibility of the authors and do not necessarily represent the official view of the National Institutes of Health.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

ARC conceived the project, designed the study, assessed eligibility of publications, extracted data, and wrote the manuscript; MNB and SJC helped design the study, assessed eligibility of publications, and extracted data; RJH helped design the study, developed the search strategies, and performed the literature search; ZL performed the statistical analyses and prepared the figures. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

The need for ethics approval was waived by the Human Subjects Office at Indiana University.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

All of the authors are associated with academic institutions, with no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary Information

Additional file 1: Supplemental Table 1.

Database search strategies.

Additional file 2: Supplemental Table 2.

Quality assessment of studies included in meta-analysis.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/. The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver (http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/) applies to the data made available in this article, unless otherwise stated in a credit line to the data.

About this article

Cite this article

Coggan, A.R., Baranauskas, M.N., Hinrichs, R.J. et al. Effect of dietary nitrate on human muscle power: a systematic review and individual participant data meta-analysis. J Int Soc Sports Nutr 18, 66 (2021). https://doi.org/10.1186/s12970-021-00463-z

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s12970-021-00463-z