Abstract

Background

Extreme exercise may alter the innate immune system. Glycans are involved in several biological processes including immune system regulation. However, limited data regarding the impact of glycan supplementation on immunological parameters after strenuous exercise are available. We aimed to determine the impact of a standardized polysaccharide-based multi-ingredient supplement, Advanced Ambrotose© complex powder (AA) on salivary secretory Immunoglobulin A (sIgA) and pro- and anti-inflammatory protein levels before and after a marathon in non-elite runners.

Methods

Forty-one male marathon runners who completed the 42.195 km of the 2016 Barcelona marathon were randomly assigned to two study groups. Of them, n = 20 (48%) received the AA supplement for 15 days prior the race (AA group) and n = 21 (52%) did not receive any AA supplement (non-AA group). Saliva and blood samples were collected the day before the marathon and two days after the end of the race. Salivary IgA, pro-inflammatory chemokines (Gro-alpha, Gro-beta, MCP-1) and anti-inflammatory proteins (Angiogenin, ACRP, Siglec 5) were determined using commercially ELISA kits in saliva supernatant. Biochemical parameters, including C-reactive protein, cardiac biomarkers, and blood hemogram were also evaluated.

Results

Marathon runners who did not receive the AA supplement experienced a decrease of salivary sIgA and pro-inflammatory chemokines (Gro-alpha and Gro-beta) after the race, while runners with AA supplementation showed lower levels of anti-inflammatory chemokines (Angiogenin). Gro-alpha and Gro-beta salivary levels were lower before the race in the AA group and correlated with blood leukocytes and platelets.

Conclusions

Changes in salivary sIgA and inflammatory chemokines, especially Gro-alfa and Gro-beta, were observed in marathon runners supplemented with AA prior to the race. These findings suggested that AA may have a positive effect on immune response after a strenuous exercise.

Similar content being viewed by others

Background

In recent years, there has been a significant increase of participants in ultra-endurance races such as marathons and ultramarathons. In the United States alone, marathon runners have increased from 25,000 in 1976 to almost 503,000 in 2010 [18]. Competing in very strenuous events imposes severe metabolic stress and causes acute responses that may negatively alter the immune system [17]. A high level of physical demand during such events induces a wide range of metabolic changes and causes micro-injuries in the muscles and other tissues. This physical demand increases the migration of white blood cells to the sites of injury, and induces acute phase inflammatory reactions [5, 16, 28]. The local response to tissue injury involves the production of a large number of acute phase proteins and cytokines related to innate immunity such as secretory Immunoglobulin A (sIgA) or inflammatory chemokines [9, 30]. Secretory Immunoglobulin A (sIgA) is a first line of defense against external agents, serving as a noninvasive biomarker of mucosal immunity [10]. Several studies have shown significant sIgA changes following strenuous exercise [3, 19, 24]. Other important immune factors present in mucosal secretion also change after prolonged running [6, 20, 24]. These changes include: pro-inflammatory chemokines, such as Gro-alpha (neutrophil-activating protein 3 and melanoma growth stimulating activity), Gro-beta (macrophage inflammatory protein, secreted by monocytes and macrophages and chemotactic for polymorphonuclear leukocytes and hematopoietic stem cells) and MCP-1 (to recruit monocytes, memory T cells, and dendritic cells to the sites of inflammation produced by either tissue injury or infection); anti-inflammatory proteins such as Angiogenin (associated with altered normality through angiogenesis and through activating gene expression that suppresses apoptosis), Adipokine ACRP30 (cell signaling protein secreted by adipose tissue involved in regulating glucose levels as well as fatty acid breakdown) and Siglec5 (Sialic acid-binding Ig-like lectin 5).

Glycans (a generic term for any sugar or assembly of sugars, in free form or attached to another molecule) are directly involved in physiology [31]. Glycans are involved in inflammation and immune system activation [11]. A standardized polysaccharide-based multi-ingredient supplement including glycans (Advanced Ambrotose© complex powder (AA)) may produce a significant overall shift towards an increased sialylation of serum glycoproteins. Sialylation changes can have a key role in many aspects of the immune response [2]. It is therefore not surprising that one of the physiological effects of these polysaccharides is the immunomodulation through the glycosylation of proteins [15]. AA is a saccharide supplement containing a standardized combination of plant polysaccharides (a source of mannose, galactose, fucose, xylose, glucose, n-acetyl-glucosamine, n-acetyl-neuraminic acid, and n-acetyl-galactosamine) that may regulate immunity. In controlled human trials, polysaccharide intake enhanced the immune system biomarkers in the blood of healthy adults [22]. The effect of dietary supplements with polysaccharides on retired professional football players supported and optimized their quality of life [25]. However, no data regarding the impact of AA supplementation on healthy marathon runners performing strenuous physical activity is available.

Our hypothesis is that glycan supplementations before strenuous physical activity enhances immune function and balances pro-inflammatory and anti-inflammatory proteins. Therefore, the aim of this study is to determine the impact of AA in the levels of sIgA, pro-inflammatory chemokines and anti-inflammatory proteins before and after running a marathon in non-elite marathoners.

Methods

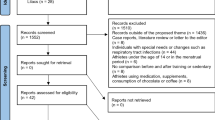

Participants

This study is a part of the SUMMIT project (Health in Ultra-Marathons and their Limits), whose objective is to evaluate the behavior of certain clinical parameters in different races and was approved by an institutional review board (IIBSP-SUMMIT-2016-02). In this study, 41 male non-elite runners of the Barcelona Marathon 2016 participated and they gave signed informed consent.

All runners were weighed on race morning within 2 h of race start in racing attire with running shoes and immediately after completing the race using the same scale Jata 565 model. Later the body mass index (BMI) was calculated using the formula BMI = weight (kg) / height (m2). The mean age was 39.3 ± 9.2 years old.

Study groups

Twenty participants (48%) received AA supplementation prior to the race (AA group), while 21 participants (52%) did not receive the AA supplement prior to the race (non-AA group). AA was administrated at dose of 8 g/day (with Arabinogalactan, Aloe Vera extract, rice starch, ghatti gum, gum Tragacanth, Glucosamine HCl, Wakame algae extract) for 15 days before the marathon. The 41 athletes were selected for being homogeneous in age, weekly training hours, years of training, weight and height (Table 1), and were randomly assigned into the two study groups.

Saliva and blood collection

Saliva samples were collected 48 h before the marathon (d0 samples) and two days after the end of the race (d2 samples). Saliva was collected into clean, sterile tubes, maintained at 4 °C before centrifugation at 9500×g 10 min at 4 °C. Supernatant was aspirated and 3 different aliquots were frozen at − 20 °C, until evaluated.

Three 10 mL blood samples were obtained from the antecubital vein 48 h before the marathon (d0 samples), at completion (d1 samples), and 48 h after the race (d2 samples). After the marathon, samples (d1) and weights were obtained within the 10 min interval after completing the race and before drinking any fluid or emptying the bladder.

Saliva analysis

Saliva samples were thawed and total saliva protein was quantified using Qubit protein Assay Kit (molecular probes Life Technologies). Salivary IgA (Human IgA, Platinum ELISA, ebioscience, Affymetrix, Santa Clare, CA), Lactoferrin, Lysozyme (AssayPro, St, Charles, MO, USA), Gro-alpha/CXCL1, Gro-beta/CXCL2 and MCP-1 (Elabscience, Houston, Texas) were measured by ELISA according to manufacturer’s instructions. Limits of detection were for IgA: 1.6 ng/ml; lactoferrin: 0.625 ng/ml; lysozyme: 0.0781 ng/ml; Gro-alpha/CXCL1: 15.63 pg/ml, Gro-beta/CXCL2: 15.63 pg/ml, MCP-1: 15.63 pg/ml, Angiogenin: 1.64 pg/ml, ARCP30: 24.69 pg/ml and Siglec 5: 6.86 pg/ml. The data was expressed as concentration of each protein relative to total saliva protein concentration.

Blood analysis

The complete blood counts were performed on the Unicel DxH800 automated hematology analyzer (Beckman Coulter, Miami, FL, USA). N-terminal pro-B-type natriuretic peptide (NT-proBNP) was quantified in whole EDTA blood using the AQT90 FLEX immunoassay (Radiometer Medical, Copenhagen, Denmark). Serum creatine kinase (CK) and C-reactive protein (CRP) were determined using the AU-5800 Chemistry Analyzer (Beckman Coulter). Troponin T was measured from serum, using a High Sensitive Troponin-T assay in a Cobas e601 platform (Roche Diagnostics, Barcelona, Spain). ST2 was measured from serum samples using a high-sensitivity sandwich monoclonal immunoassay (Pressage® ST2 assay, Critical Diagnostics, San Diego, CA, USA).

Statistical analysis

The Kolmogorov-Smirnov test was applied to test the normal distribution of the data. All variables, with a normal distribution, were reported as mean ± standard deviation (SD). The rest of the variables were reported as median (interquartile rank) (IQR). T-test and paired t-test were respectively used for the comparison of independent and related variables with normal distribution. Wilcoxon test was used for the comparison of related variables with non-normally distributed data. Pearson’s and Spearman’s coefficients were respectively used to correlate changes between normal and between non-normal distributed variables. ANOVA and Kruskal-Wallis test were respectively used for comparative analyses of multiple normal and non-normal distributed data. Chi-square tests were used for the comparison of frequencies. P values less than 0.05 were considered significant.

Results

Study participants

Forty-one male non-elite marathon runners completed the 42.195 km of the 2016 Barcelona Marathon. Mean finishing time was 3 h and 28 min ± 0. 41 h. Median (interquartile range) age was 39 ± 9 years old, with a weight of 77 ± 11 kg, height of 178 ± 8 cm and Body Mass Index (BMI) of 24.1 ± 3.4. Median training years were 8 ± 8, with a median of 7 ± 5 h per week.

No significant differences in age, weight, height, and training were found between runners who received AA supplementation and those who did not (Table 1).

Plasma and blood measurements

C-reactive protein increased significantly 48 h after the marathon (d2), although no significant differences between AA and non-AA groups were found. Similarly, all evaluated cardiac (Hs-TnT, St2 and NTproBNP) and muscle damage (CK) biomarkers increased after the race, but no significant differences between participants in either group were found (Table 2).

Hemoglobin, hematocrit, erythrocytes and platelets counts did not change after the race (d1), with no differences between groups. However, a marked increase in leukocyte counts per L was found in both groups after the race (d1) and participants who received AA supplementation for 15 days prior to the race experienced a lower increase compared to those without the AA supplementation (13.2 ± 4.6 vs 16.1 ± 4.4 × 109/L, p = 0.03) (Table 2).

Salivary IgA

No differences in salivary IgA levels normalized to total salivary protein before (d0) and 48 h after the race (d2) were found (0.47 ± 0.44 vs 0.37 ± 0.29, p = 0.6). However, when participants with and without AA supplementation were compared, a decrease of sIgA 48 h after the race (d2) was observed in the non-AA group (0.55 ± 0.37 vs 0.31 ± 0.35, p = 0.01), while no differences before (d0) and 48 h after the race (d2) in the AA group were found (0.25 ± 0.33 vs 0.24 ± 0.32, p = 0.5) (Fig. 1).

Salivary pro inflammatory proteins

A decrease of pro-inflammatory salivary proteins such as Gro-alfa, Gro-beta and MCP-1 after the race was observed in all participants, although differences were not statistically significant (data not shown). Nevertheless, the decline in Gro-alpha (Fig. 2a) and Gro-beta (Fig. 2b) was statistically significant in those runners who did not receive the AA supplement (0.38 ± 0.20 vs 0.24 ± 0.18, p = 0.02 and 0.47 ± 0.26 vs 0.32 ± 0.26, p = 0.03), while differences were not observed in the AA group. Furthermore, basal levels of Gro-alpha and Gro-beta were significantly lower (p = 0.03) in the AA group at baseline before the marathon (d0) compared to the non-AA group (Fig. 2).

Salivary anti-inflammatory proteins

No statistically significant differences of salivary anti-inflammatory proteins such as ACRP, angiotensin, and Siglec 5 were observed before (d0) and 48 h after the marathon (d2) (data not shown). However, in those runners of the AA group, a significant decrease of Angiogenin 48 h after the race (d2) was observed (0.18 ± 0.08 vs 0.14 ± 0.07, p = 0.04), while differences were not observed in the non-AA group (0.3 ± 0.13 vs 0.17 ± 0.10, p = 0.7) (Fig. 3).

Systemic correlations

After the race, those runners who received the AA supplement (AA group) showed positive correlations between salivary Gro-alpha levels with leukocyte counts per L (r = 0.38, p = 0.02) and a tendency between Gro-beta salivary levels and blood platelet counts (r = 0.27, p = 0.06). These systemic correlations were not observed in the non-AA group (Fig. 4).

Discussion

In our study, we demonstrated significant changes in salivary biomarkers of immune function in healthy, non-elite athletes before and after a strenuous exercise like an asphalt marathon, after consuming a polysaccharide-based multi-ingredient supplement, AA, for 15 days prior to exercise. Specifically, a decrease in salivary sIgA, Gro-alfa and Gro-beta were observed after the marathon in those runners who did not receive AA supplement prior the race, while those runners who received the AA supplement showed a decrease in a salivary Angiogenin. Gro-alpha and Gro-beta salivary levels were lower before the race in the AA group and correlated with the counts of blood leukocytes and platelets. These findings suggest that AA supplementation produces changes in salivary immunity that may have a positive effect on immunity before and after a marathon.

sIgA is a key component of innate immunity and provides a first line of defense against pathogens at mucosal surfaces [8]. Numerous studies have assessed the saliva sIgA response to prolonged strenuous exercise to explore whether immunity may be temporarily compromised after the exercise. Most of the studies described a post-exercise decrease in sIgA, including Nordic skiers after a 50 km race [29] or trained cyclists cycling for more than 2 h on a stationary ergometer [32]. In marathon runners, a significant decrease of sIgA following a marathon race has been described [19], which was independent of gender, age or carbohydrate ingestion. In our study, runners with AA supplementation did not experience a significant decrease in sIgA after the marathon, which was observed in runners without the AA. These findings suggested that AA supplement enhanced immunity by avoiding the sIgA decrease after the race. Different studies have postulated that glycosylation plays an important role in the biosynthesis and biological activity of the proteins involved in antigen recognition, such as sIgA [23]. Further studies are needed to explore this pathway, which may be crucial in order to better understand the effect of strenuous exercise on mucosal immunity.

Supplementation with glycans can also result in salivary glycol-modifications of proteins. These modifications can regulate the synthesis and/or degradation of pro- and anti-inflammatory molecules participating in the immune response of runners to strenuous effort. Several inflammatory chemokines have demonstrated a potential role in the regulation of immune response during exercise [27]. In our study, we demonstrated that Gro-alfa and Gro-beta, two pro-inflammatory chemokines, involved in the attraction of neutrophils to the site of inflammation, decreased in saliva after the race in those runners who did not receive AA. It has been described that moderate exercise suppressed Gro-alfa [4] and, in experimental models, exercise down-regulates multiple inflammatory cytokines [26], including Gro-alfa and Gro-beta, that results in a systemic anti-inflammatory effect [1, 13]. These findings were not observed in runners who received the AA supplement, suggesting that they had better immunoregulation. Runners with AA supplementation have also showed a decrease in salivary Angiogenin levels, which was not detected in runners without AA. It suggests that salivary pro-inflammatory proteins can be buffered with anti-inflammatory ones, especially those produced by runners supplemented with AA. In addition, it is important to note that after 15 days on AA, the baseline levels of Gro-alfa, Gro-beta and Angiogenin were different in runners with and without AA. Interpretations of all these salivary inflammatory changes are complex and require further more detailed studies.

The systemic effect of glycans has been described in several studies [15]. Interestingly, it is postulated that glycans may regulate leukocyte activity [21]. In our study, runners who received the AA supplement experienced a lower increase in total blood leukocyte counts after the race compared to those runners without the AA supplement. Furthermore, a correlation between salivary levels of Gro-alpha with blood leukocyte counts and salivary Gro-beta levels with blood platelet counts were observed in the AA group. All in all, these findings suggested a relationship between salivary and systemic immunity, especially in those runners who received the AA supplement prior to the race. The association between high dietary protein during high-intensity training and reduction in respiratory symptoms in elite cyclists by restoring impairments in leukocyte trafficking has also been reported [35] The influence of ingredients other than glycans on the immune system has been reported. For example, brown seaweed [33], Aloe vera [12] and glucosamine [14] have antioxidant activity and anti-inflammatory effects. Arabinogalactan decreases the incidence of infectious episodes by improving serum-antigen specific IgG and IgE response to Streptococcus pneumonia [7]. Starch supplementation promotes the growth of commensal bacteria that may improve bowel health [34]. However, more work is needed to clarify the mechanism that may explain these important results.

Our study has limitations. First, we only have studied men, and we cannot exclude the effect of glycans in salivary immunity based on sex. Second, due to the small sample size of runners included, the results should be validated in further studies before generalizing them. Third, runners received the AA supplement for 15 days prior the race, and the effect of taking this supplement for a longer time may be different. Fourth, the influence of ingredients included in the AA supplements which are not glycans such as glucosamine and Aloe Vera on the immune system cannot be ruled out, and further studies in non-elite marathon runners should be performed to better clarify this important point.

Conclusion

In conclusion, our study documented significant changes in salivary and systemic immunological biomarkers in marathon runners after consuming a polysaccharide-based multi-ingredient supplement AA, before and after the race. Further research using randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled design will extend knowledge of the potential benefits nutritional dietary supplementation with polysaccharides may have in marathon runners.

Abbreviations

- AA:

-

Standardized dietary plant-derived polydisperse polysaccharide Advanced Ambrotose© complex powder

- BMI:

-

Body mass index

- CK:

-

Serum creatine kinase

- CRP:

-

C-reactive protein

- HGB:

-

Hemoglobin

- Hs-TnT:

-

High-sensitivity troponin T

- NT-proBNP:

-

N-terminal pro-B-type natriuretic peptide

- sIgA:

-

Salivary secretory Immunoglobulin A

References

Accattato F, Greco M, Pullano SA, Carè I, Fiorillo AS, Pujia A, Montalcini T, Foti DP, Brunetti A, Gulletta E. Effects of acute physical exercise on oxidative stress and inflammatory status in young, sedentary obese subjects. PLoS One. 2017;12(6):1–13.

Alavi A, Fraser O, Tarelli E, Bland M, Axford J. An open-label dosing study to evaluate the safety and effects of a dietary plant-derived polysaccharide supplement on the N-glycosylation status of serum glycoproteins in healthy subjects. Eur J Clin Nutr. 2011;65:648–56.

Allgrove JE, Geneen L, Latif S, Gleeson M. Influence of a fed or fasted state on the s-IgA response to prolonged cycling in active men and women. Int J Sport Nutr Exerc Metab. 2009;19(3):209–21.

Aqel SI, Hampton JM, Bruss M, Jones KT, Valiente GR, Wu LC, Young MC, Willis WL, Ardoin S, Agarwal S, Bolon B, Powell N, Sheridan J, Schlesinger N, Jarjour WN, Young NA. Daily moderate exercise is beneficial and social stress is detrimental to disease pathology in murine lupus nephritis. Front Physiol. 2017;8(236):1–11.

Bessa A, Nissenbaum M, Monteiro A, Gandra PG, Nunes LS, Bassini-Cameron A, Werneck-de-Castro JPS, Macedo DV, Cameron LC. High-intensity ultraendurance promotes early release of muscle injury markers. Br J Sports Med. 2008;42:889–93.

Catoire M, Mensink M, Kalkhoven E, Schrauwen P, Kersten S. Identification of human exercise-induced myokines using secretome analysis. Physiol Genomics. 2014;46:256–67.

Dion C, Chappuis E, Ripoll C. Does larch arabinogalactan enhance immune function? A review of mechanistic and clinical trials. Nutr Metab. 2016;13(28):1–11.

Gleeson M. Mucosal immunity and respiratory illness in elite athletes. Int J Sports Med. 2000;21(1):S33–43.

Gleeson M, Bishop NC. URI in athletes: are mucosal immunity and cytokine responses key risk factors? Exerc Sport Sci Rev. 2013;41(3):148–53.

Hangstock HG, Walsh NP, Edwards JP, Fortes MB, Cosby SL, Nugent A, Curran T, Coyle PV, Ward MD, Yong XHA. Tear fluid SIgA as a noninvasive biomarker of mucosal immunity and common cold risk. Med Sci Sports Exerc. 2016;48(3):569–77.

Hart GW, Copeland RJ. Glycomics hits the big time. Cell. 2010;143(5):672–6.

Hart LA, Nibbering PH, Barselaar MT, Dijk H, Berg AJJ, Labadie RP. Effects of low molecular constituents from Aloe Vera gel on oxidative metabolism and cytotoxic and bactericidal activities of human neutrophils. Int J Immunopharmacol. 1990;12(4):427–34.

Huber Y, Gehrke N, Biedenbach J, Helmig S, Simon P, Straub BK, Bergheim I, Huber T, Schuppan D, Galle PR, Wörns MA, Schuchmann M, Schattenberg JM. Voluntary distance running prevents TNF-mediated liver injury in mice through alterations of the intrahepatic immune milieu. Cell Death Dis. 2017;8(6):1–10.

Jerosch J. Effects of glucosamine and chondroitin sulfate on cartilage metabolism in OA: outlook on other nutrient partners especially omega-3 fatty acids. Int J Rheumatol. 2011;969012:1–17.

Johnson JL, Jones MB, Ryan SO, Cobb BA. The regulatory power of glycans and their binding partners in immunity. Trends Immunol. 2013;34(6):290–8.

Kim HJ, Lee YH, Kim CK. Biomarkers of muscle and cartilage damage and inflammation during a 200 km run. Eur J Appl Physiol. 2007;99(4):443–7.

Kłapcińska B, Waśkiewicz Z, Chrapusta SJ, Sadowska-Krępa E, Czuba M, Langfort J. Metabolic responses to a 48-h ultra-marathon run in middle-aged male amateur runners. Eur J Appl Physiol. 2013;113(11):2781–93.

Marathon Guide. http://www.marathonguide.com/Features/Articles/2010RecapOverview.cfm. Accessed 12 October 2014.

Nieman DC, Henson DA, Fagoaga OR, Utter AC, Vinci DM, Davis JM, Nehlsen-Cannarella SL. Change in salivary IgA following a competitive marathon race. Int J Sports Med. 2002;23(1):69–75.

Pedersen L, Olsen CH, Pedersen BK, Hojman P. Muscle-derived expression of the chemokine CXCL1 attenuates diet-induced obesity and improves fatty acid oxidation in the muscle. AJP Endocrinol Metab. 2012;302:E831–40.

Rabinovich GA, Croci DO. Regulatory circuits mediated by lectin-glycan interactions in autoinmunity and cancer. Immunity. 2012;36:322–35.

Ramberg JE, Nelson ED, Sinnott R. Immunomodulatory dietary polysaccharides: a systematic review of the literature. Nutr J. 2010;9(54):1–22.

Rudd PM, Elliott T, Cresswell P, Wilson IA, Dwek RA. Glycosilation and the immune system. Science. 2001;291(5512):2370–6.

Sibila O, Suarez-Cuartin G, Rodrigo-Troyano A, Fardon TC, Finch S, Mateus EF, Garcia-Bellmunt L, Castillo D, Vidal S, Sanchez-Reus F, Restrepo MI, Chalmers JD. Secreted mucins and airway bacterial colonization in non-CF bronchiectasis. Respirology. 2015;20:1082–8.

Sinnott R, Maddela RL, Bae S, Best T. The effect of dietary supplements on the quality of life of retired professional football players. Global J Health Sci. 2013;5(2):13–26.

Szalai Z, Szász A, Nagy I, Puskás LG, Kupai K, Király A, Berkó AM, Pósa A, Strifler G, Baráth Z, Nagy LI, Szabó R, Pávó I, Murlasits Z, Gyöngyösi M, Varga C. Anti-inflammatory effect of recreational exercise in TNBS-induced colitis in rats: role of NOS/HO/MPO system. Oxidative Med Cell Longev. 2014;925981:1–11.

Terra R, da Silva SAG, Pinto VS, Dutra PML. Effect of exercise on the immune system: response, adaptation and cell signaling. Rev Bras Med do Esporte. 2012;18(3):208–14.

Tidball JG. Inflammatory processes in muscle injury and repair. Am J Physiol Regul Integr Comp Physiol. 2005;288:R345–53.

Tomasi TB, Trudeau FB, Czerwinski D, Erredge S. Immune parameters in athletes before and after strenuous exercise. J Clin Inmunol. 1982;2(3):173–8.

Trochimiak T, Hubner-Wozniak E. Effect of exercise on the level of immunoglobulin a in saliva. Biol Sport. 2012;29:255–61.

Varki A, Cummings RD, Esko JD, Freeze HH, Stanley P, Bertozzi CR, Hart GW, Etzler ME. Essentials in Glycobiology. Cold Spring Harbor: Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory Press; 2009.

Walsh NP, Bishop NC, Blackwell J, Wierzbicki SG, Montague JC. Salivary IgA response to prolonged exercise in a cold environment in trained cyclists. Med Sci Sports Exerc. 2002;34(10):1632–7.

Wang X, Cui Y, Qi J, Zhu M, Zhang T, Cheng M, Liu S, Wang G. Fucoxanthin exerts Cytoprotective effects against hydrogen peroxide-induced oxidative damage in L02 cells. Biomed Res Int. 2018;1085073:1–11.

West NP, Christophersen CT, Pyne DB, Cripps AW, Conlon MA, Topping DL, Kang S, McSweeney CS, Fricker PA, Aguirre D, Clarke JM. Butyrylated starch increases colonic butyrate concentration but has limited effects on immunity in healthy physically active individuals. Exerc Immunol Rev. 2013;19:102–19.

Witard OC, Turner JE, Jackman SR, Kies AK, Jeukendrup AE, Bosch JA, Tipton KD. High dietary protein restores overreaching induced impairments in leukocyte trafficking and reduces the incidence of upper respiratory tract infection in elite cyclists. Brain Behav Immun. 2014;39:211–9.

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to thank the Barcelona marathon organization for their cooperation, UPC students for their help in data collection, Hospital Universitari Germans Trias i Pujol and Hospital de la Santa Creu i Sant Pau for data analysis, and finally the marathon runners for their participation.

Funding

This study was funded by an unconditional product grant from Mannatech Inc. (Coppell, TX). The researchers in this study independently collected, analyzed, and interpreted the results from this study and have no financial interests in the results of this study.

Availability of data and materials

The datasets used and/or analyzed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

All authors participated at the conception and design of the study. ER and LN were involved at data collection. All authors participated at data interpretation and analysis. ER, EC, OS and SV participated at manuscript drafting. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

As discussed in the Participants section of the manuscript, this study was approved by an institutional review board. Protocol number: IIBSP-SUMMIT-2016-02. All participants provided written consent prior to their participation in the study.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The study was started prior to the corresponding author, Emma Roca joining the Global Scientific Advisory Board (GSAB)* at Mannatech, Inc. as related research to her PhD studies. The study was approved by the supervising Faculty/Professor and the University (Universitat Politècnica de Catalunya (UPC), Research Centre for Biomedical Engineering (CREB-UPC) and IRB without input from Mannatech, Inc.

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made. The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver (http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/) applies to the data made available in this article, unless otherwise stated.

About this article

Cite this article

Roca, E., Cantó, E., Nescolarde, L. et al. Effects of a polysaccharide-based multi-ingredient supplement on salivary immunity in non-elite marathon runners. J Int Soc Sports Nutr 16, 14 (2019). https://doi.org/10.1186/s12970-019-0281-z

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s12970-019-0281-z