Abstract

Background

Paediatric rheumatic diseases are a leading cause of acquired disability in Southeast Asia and Asia-Pacific Countries (SE ASIA/ASIAPAC). The aims of this study were to identify and describe the challenges to the delivery of patient care and identify solutions to raise awareness about paediatric rheumatic diseases.

Methods

The anonymised online survey included 27 items about paediatric rheumatology (PR) clinical care and training programmes. The survey was piloted and then distributed via Survey-Monkey™ between March and July 2019. It was sent to existing group lists of physicians and allied health professionals (AHPs), who were involved in the care pathways and management of children with rheumatic diseases in SE ASIA/ASIAPAC.

Results

Of 340 participants from 14 countries, 261 participants had been involved in PR care. The majority of the participants were general paediatricians. The main reported barriers to providing specialised multidisciplinary service were the absence or inadequacy of the provision of specialists and AHPs in addition to financial issues. Access to medicines was variable and financial constraints cited as the major obstacle to accessing biological drugs within clinical settings. The lack of a critical mass of specialist paediatric rheumatologists was the main perceived barrier to PR training.

Conclusions

There are multiple challenges to PR services in SE ASIA/ASIAPAC countries. There is need for more specialist multidisciplinary services and greater access to medicines and biological therapies. The lack of specialist paediatric rheumatologists is the main barrier for greater access to PR training.

Similar content being viewed by others

Background

Paediatric rheumatic diseases encompass a spectrum of inflammatory conditions including juvenile idiopathic arthritis (JIA). These conditions remain the leading cause of acquired disability in children [1, 2]; risk factors for worse outcome include delay to diagnosis, poor access to appropriate therapies, inadequate specialist services, lack of relevant guidelines being available and children living in countries with worse socioeconomic status [2,3,4].

There are severe workforce challenges across the globe but especially so in Asia with one paediatric rheumatologist for every 26 million children [2]; this contrast markedly with the recommendations for Europe and North America with one paediatric rheumatologist per 0.42 and 0.25 million children respectively [2]. Although an increase in numbers of rheumatologists and rheumatology trainees were reported [5, 6], there were still limited access to paediatric rheumatologists in Southeast Asia [7]; thus most children with rheumatic diseases were treated mainly by adult rheumatologists and general paediatricians [8, 9].

Currently, several recommendations for standards of care as well as treatment for children with rheumatic diseases have been developed by international paediatric rheumatology associations consisting of experts mainly from high resource income countries (HRIC) [10,11,12,13,14,15,16,17,18]. These guidelines are not always transferable to clinical practice in middle resource income countries (MRIC) and low resource income countries (LRIC) where there are limited resources and other health care challenges as priorities for health services [19]. The Juvenile Arthritis Management in less resourced countries (JAMLess) recommendations were the first to be aimed at LRIC [19] and highlighted principles to support and develop paediatric rheumatology (PR) including the need to contextually relevant guidance for clinical management, treatments, referrals, monitoring, education and training, advocacy, networks, policy and research. The JAMLess was originally intended for developing recommendations in less resourced countries and focused on JIA, although many of the questions were generic to service delivery in PR [19].

The aims of this study were to build on the previous work from JAMLess [19] to identify and describe the challenges and potential solutions to improve the patient care and raise awareness of paediatric rheumatic diseases in Southeast Asia and Asia-Pacific Countries (SE ASIA/ASIAPAC).

Methods

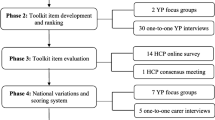

The anonymised online survey was developed in collaboration with members of the JAMLess group (CS, HF), using essentially the same questionnaire with 27 items, divided into two major themes; PR awareness-clinical care and PR training programmes among SE ASIA/ASIAPAC. The online survey was piloted and then distributed to clinicians (doctors, nurses, allied health professionals (AHPs)) in the SE ASIA/ASIAPAC regions; recipients were known to be involved in PR clinical care or through general paediatric networks known to have potential to be exposed to children with rheumatic diseases. Participants were sent the link to the survey using existing social media professional groups (WhatsApp™) or by email and were asked to share the link of the survey. No reminders were sent out. The data were collected electronically through the survey online via Survey-Monkey™ between March and July 2019. Anonymity and confidentiality were maintained for all participants throughout the survey.

The survey included questions about the participant (job role, country of work, health care setting, duration of practice, postgraduate PR training, percentage of time devoted to PR patients), opinion about barriers to diagnosis of paediatric rheumatic patients, access to medications including disease modifying antirheumatic drugs (DMARDs) and biological drugs, provision of the multidisciplinary team (MDT) and any additional challenges or barriers affecting clinical care with free text comments. There were also questions about PR training and the type of PR teaching offered (e.g lectures, clinical examination skills and clinical rotation opportunities). Descriptive statistics were used to analyse and present the survey results using collation software provided by Survey-Monkey™.

Results

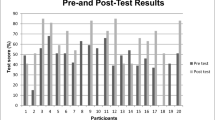

There were 340 participants from a total of 14 countries (Fig. 1); the total number of invited participants was unknown so a response rate could not be calculated. The majority of respondents, 261/340 (77.2%) were involved in PR care; most were general paediatricians (52.1%), followed by adult rheumatologists (18.5%), paediatric rheumatologists (15%), and ‘other’ specialists (11.2%; 16 paediatric nephrologists, 5 paediatric allergists, 4 paediatric orthopaedic surgeons, 3 neonatologists, 3 paediatric cardiologists, 1 paediatric haemato-oncologist, 1 paediatric infectious disease specialist, 1 paediatric pulmonologist, and 4 others not identified), 5 general practitioners (1.5%) and others (1.5%); 1 nurse, 2 medical students, 2 medical officers respectively, as shown in Table 1. The term ‘specialist’ is conventionally defined as a physician with specialist certification in their respective country. The majority of participants (59.1%) devoted < 25% of their time to caring children with rheumatic diseases. The duration of clinical practice was broad ranging from < 5 to > 40 years with the majority (27.4%) being 5 to 10 years. Most (41.5%) participants worked in government-funded (public sector) practices, 38.8% in academic centres/ teaching hospitals, and 28.5% in private practice, with the remainder in a mix of state-run/government-funded and private practice. The details of practice settings, number of years in practice and time devoted to PR care as shown in Table 1.

Paediatric rheumatology awareness and clinical care delivery

Participants reported that paediatric rheumatologists mainly cared for children with rheumatic diseases (44.9%), followed by general paediatricians (38%) and adult rheumatologists (8.1%). The MDT members involved in patient care included general paediatricians (80.8%), paediatric rheumatologists (57.3%), physiotherapists (49.2%), occupational therapists (31.2%), adult rheumatologists (27.8%) and specialist rheumatology nurses (15%) as shown in Fig. 2.

The perceived five main barriers to prompt diagnosis of paediatric rheumatic diseases were: 1) insufficient training about childhood rheumatic diseases amongst paediatricians and other AHPs (64.1%): 2) lack of awareness of paediatric rheumatic diseases amongst AHPs (53.4%): 3) lack of awareness of paediatric rheumatic diseases within the general public population (51.3%): 4) lack of specialised paediatric rheumatologists to refer patients to (49.2%): and 5) lack of paediatric rheumatology MDT (48.3%) as shown in Fig. 3.

The main barriers to providing a specialised multidisciplinary PR service in the clinical settings were the absence or inadequacy of provision of specialists (68.2%), the absence or inadequacy of provision of AHPs (49.8%) and financial constraints (43.8%).

There was very variable access to medications in the countries represented in the survey as shown in Tables 2 and 3. Most countries (with the exception of Laos) had access to DMARDS, parenteral corticosteroids and intra-articular steroids (albeit different corticosteroid preparations available). Access to biological therapies was very variable with Singapore having access to all biologics and many other countries having access to few or none (e.g. Indonesia, Laos, Vietnam and Nepal). There was generally very low accessibility to biosimilars; availability of tumour necrosis factor biosimilars (Etanercept, Infliximab) and rituximab biosimilar were reported in Australia, India, Malaysia, Pakistan, the Philippines, Singapore and Thailand whilst other countries reported having access to none. The majority of participants reported financial constraints (62.1%) being the main barrier to accessing biological drugs for patients even if they were available in their countries, followed by non-availability of biological drugs (37.1%) and absence of appropriate specialists to prescribe biological drugs (34.4%).

The main challenges affecting clinical care included 1) low socioeconomic status (69.6%), 2) a general delay to access health care system (63.1%), 3) comorbidities such as infection burden (46.1%) and limited access to physical therapy such as physiotherapy and occupational therapy (46.1%), as shown in Fig. 4.

Finally, all participants were asked to share their opinions on how to improve PR clinical care delivery in their setting. Most agreed that there was need for more paediatric rheumatologists (84.9%), specialist therapists (74.8%) and rheumatology nurses (65.1%) as well as more paediatric MSK training programmes for paediatricians and family medicine physicians (73.4%) to raise awareness and facilitate diagnosis and referral.

Paediatric rheumatology training

From this survey there appear to be limited opportunities for PR education including lectures, teaching of MSK examination skills and clinical rotation opportunities at the teaching hospitals or universities at both undergraduate and postgraduate levels. There was very low training especially to nurses, AHPs as well as adult rheumatology and general practice trainees. In terms of postgraduate training, the main perceived barriers to PR training were lack of a critical mass of trained paediatric rheumatologists to supervise trainees (42.2%), lack of interested applicants to the programme (33.6%) and lack of funding for PR training positions (33.2%) as shown in Fig. 5. These barriers led to no existing PR training programme for 62.6% of the participants in the country where they were in clinical practice.

Discussion

This is the first survey describing PR clinical care and training in SE ASIA/ASIAPAC regions and highlighted multiple challenges. Our results demonstrated the paucity of trained paediatric rheumatologists and specialist MDTs as the main perceived barrier to improving PR clinical care. Paediatric rheumatologists also have key roles in education and training leadership, advocacy, policy development and research which are likely to impact on clinical care capacity building. Previous studies from mostly HRIC and MRIC regions demonstrate the global scarcity of paediatric rheumatologists [2, 5, 6, 20,21,22]; the scarcity is most severe in Africa and Asia, unfortunately in the most populous countries and where there are large numbers of children affected [23].

More PR training programmes are needed [7] and there is need to encourage and support paediatricians to further their training in PR although remains a major challenge given other health care priorities and the lack of paediatricians in many LRIC/MRIC countries [24]. It is therefore imperative for greater efforts to increase awareness and knowledge about PR amongst general paediatricians, other doctors (orthopaedic surgeons, adult rheumatologists), nurses and AHPs who may be the first health care professionals to encounter children with potential rheumatic diseases [19]. Such health care professionals need targeted education and training relevant to their clinical context to enable them to make an accurate diagnosis, be involved in patient care and refer to specialists where available. The PR training is currently developing in some SEA countries, namely Singapore, Malaysia, the Philippines and Thailand. Furthermore, there is need to increase awareness in the general population to encourage early presentation to health care through campaigns (e.g World Young Rheumatic Disease (WORD) Day; https://wordday.org) [25].

The other main perceived barrier to clinical care in SE ASIA/ASIAPAC was affordability, availability and access of medicines (DMARDs and biologics). The variation in availability of biologics in our survey was notable and even in countries regarded as HRIC (e.g Australia and New Zealand). Financial constraints, absence of specialists to supervise the use of biological drugs in clinical practice and drug unavailability are all major barriers to the use of these medicines. The prescribing and monitoring of biological therapies for children with rheumatic diseases is recommended to be under the supervision of specialists [15,16,17, 19]; therefore, a paucity of specialists is likely a major barrier to access such therapies. Limited access and availability of conventional DMARDs, intraarticular corticosteroids and biological drugs have been reported in other LRIC [9, 26]. The important role of the WHO Essential Medicines List (EML) and need to include medicines used in PR care has been highlighted [27]; revision of the EML is a priority for the PR community to address and if successful, will hopefully improve access to these medicines in many LRIC.

Recommendations and guidelines for clinical care are important levers for change but have been mainly developed within HRIC [10,11,12,13,14,15,16,17,18] and not transferable to LRIC in the context of other health challenges, poverty and burden of infection [19]. The JAMLess recommendations [19] are the first of their kind for LRIC and most respondents to their surveys were from Africa, Asia and South America. Broadly speaking, our results from SE ASIA/ASIAPAC are similar to those reported in the JAMLess survey; highlighting need for workforce capacity building, greater access to PR training, specialist care and medicines, and targeted educational programmes to raise awareness [28,29,30,31]. The SE ASIA/ASIAPAC region has wide diversity in terms of socioeconomic status, population density, disease burden and health care systems. The JAMLess recommendations are likely broadly applicable to SE ASIA/ASIAPAC but more work is needed to produce contextually relevant clinical guidelines.

There are limitations in our study. First, there is likely a selection bias of participants in the survey. Due to the paucity of paediatric rheumatologists in many of the countries surveyed, there were unequal distribution in the responses across some countries. Our survey study was not a population-based study. We sent the link of questionnaires through paediatric networks with potential to reach clinicians involved in clinical care for children with rheumatic diseases. Most responders were from Malaysia, Myanmar and Thailand. It was challenging to involve all hospitals in each country but we believe that as a minimum, tertiary care centres in all the participating countries were represented. Additionally, our survey data found that 223 out of 340 participants responded the question relating to training in PR. The other (117) responders skipped this question. We assumed that the 223 responders had awareness of training in PR in their respective countries and of these, 51 (22.9%) were paediatric rheumatologists. Second, the online survey was in English version and was sent through email and WhatsApp™ so we were unable to ascertain the response rate. Thirdly, areas with dedicated PR care are probably more likely to have responded to this survey and countries without dedicated PR care are inevitably less well represented.

Conclusions

To the best of our knowledge, this is the first survey of PR clinical care and training in SE ASIA/ASIAPAC and highlights multiple challenges. The Paediatric Global Musculoskeletal Task Force [32] has recently published a ‘Call to Action’ [33] and increasing public and government awareness is important. Facilitating and leveraging change needs support and action from health authorities, higher education institutions and policy makers. We hope that this survey is the initial step for further collaborative working to address many of these challenges and ultimately improve the quality of care for children with rheumatic diseases in the region.

Availability of data and materials

Not applicable

Abbreviations

- AHPs:

-

Allied health professionals

- ACR:

-

American College of Rheumatology

- DMARDs:

-

Disease modifying antirheumatic drugs

- EML:

-

Essential Medicines List

- EULAR:

-

European League Against Rheumatism

- HRIC:

-

High resource income countries

- JAMLess:

-

Juvenile Arthritis Management in less resourced countries

- LRIC:

-

Low resource income countries

- MDT:

-

Multidisciplinary team

- MSK:

-

Musculoskeletal

- MRIC:

-

Middle resource income countries

- NSAIDs:

-

Nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs

- PR:

-

Paediatric rheumatology

- SHARE:

-

Single Hub and Access point for paediatric Rheumatology in Europe

- SE ASIA/ASIAPAC:

-

Southeast Asia and Asia-Pacific Countries

References

Foster H, Rapley T. Access to pediatric rheumatology care -- a major challenge to improving outcome in juvenile idiopathic arthritis. J Rheumatol. 2010;37(11):2199–202.

Henrickson M. Policy challenges for the pediatric rheumatology workforce: Part III. the international situation. Pediatr Rheumatol Online J. 2011;9:26.

Foster HE, Eltringham MS, Kay LJ, Friswell M, Abinun M, Myers A. Delay in access to appropriate care for children presenting with musculoskeletal symptoms and ultimately diagnosed with juvenile idiopathic arthritis. Arthritis Rheum. 2007;57(6):921–7.

Consolaro A, Giancane G, Alongi A, van Dijkhuizen EHP, Aggarwal A, Al-Mayouf SM, et al. Phenotypic variability and disparities in treatment and outcomes of childhood arthritis throughout the world: an observational cohort study. Lancet Child Adolesc Health. 2019;3(4):255–63.

Reveille JD, Munoz R, Soriano E, Albanese M, Espada G, Lozada CJ, et al. Review of current workforce for rheumatology in the countries of the Americas 2012-2015. J Clin Rheumatol. 2016;22(8):405–10.

Cox A, Piper S, Singh-Grewal D. Pediatric rheumatology consultant workforce in Australia and New Zealand: the current state of play and challenges for the future. Int J Rheum Dis. 2017;20(5):647–53.

Arkachaisri T, Tang SP, Daengsuwan T, Phongsamart G, Vilaiyuk S, Charuvanij S, et al. Paediatric rheumatology clinic population in Southeast Asia: are we different? Rheumatology (Oxford). 2017;56(3):390–8.

Correll CK, Spector LG, Zhang L, Binstadt BA, Vehe RK. Barriers and alternatives to pediatric rheumatology referrals: survey of general pediatricians in the United States. Pediatr Rheumatol Online J. 2015;13:32.

Dahman HAB. Challenges in the diagnosis and management of pediatric rheumatology in the developing world: lessons from a newly established clinic in Yemen. Sudan J Paediatr. 2017;17(2):21–9.

Groot N, de Graeff N, Avcin T, Bader-Meunier B, Brogan P, Dolezalova P, et al. European evidence-based recommendations for diagnosis and treatment of childhood-onset systemic lupus erythematosus: the SHARE initiative. Ann Rheum Dis. 2017;76(11):1788–96.

Bellutti Enders F, Bader-Meunier B, Baildam E, Constantin T, Dolezalova P, Feldman BM, et al. Consensus-based recommendations for the management of juvenile dermatomyositis. Ann Rheum Dis. 2017;76(2):329–40.

Foster HE, Minden K, Clemente D, Leon L, McDonagh JE, Kamphuis S, et al. EULAR/PReS standards and recommendations for the transitional care of young people with juvenile-onset rheumatic diseases. Ann Rheum Dis. 2017;76(4):639–46.

de Graeff N, Groot N, Ozen S, Eleftheriou D, Avcin T, Bader-Meunier B, et al. European consensus-based recommendations for the diagnosis and treatment of Kawasaki disease - the SHARE initiative. Rheumatology (Oxford). 2019;58(4):672–82.

de Graeff N, Groot N, Brogan P, Ozen S, Avcin T, Bader-Meunier B, et al. European consensus-based recommendations for the diagnosis and treatment of rare paediatric vasculitides - the SHARE initiative. Rheumatology (Oxford). 2019;58(4):656–71.

Beukelman T, Patkar NM, Saag KG, Tolleson-Rinehart S, Cron RQ, DeWitt EM, et al. 2011 American College of Rheumatology recommendations for the treatment of juvenile idiopathic arthritis: initiation and safety monitoring of therapeutic agents for the treatment of arthritis and systemic features. Arthritis Care Res. 2011;63(4):465–82.

Ringold S, Weiss PF, Beukelman T, DeWitt EM, Ilowite NT, Kimura Y, et al. 2013 update of the 2011 American College of Rheumatology recommendations for the treatment of juvenile idiopathic arthritis: recommendations for the medical therapy of children with systemic juvenile idiopathic arthritis and tuberculosis screening among children receiving biologic medications. Arthritis Rheum. 2013;65(10):2499–512.

Ringold S, Angeles-Han ST, Beukelman T, Lovell D, Cuello CA, Becker ML, et al. 2019 American College of Rheumatology/Arthritis Foundation guideline for the treatment of juvenile idiopathic arthritis: therapeutic approaches for non-systemic polyarthritis, Sacroiliitis, and Enthesitis. Arthritis Rheum. 2019;71(6):846–63.

Angeles-Han ST, Ringold S, Beukelman T, Lovell D, Cuello CA, Becker ML, et al. 2019 American College of Rheumatology/Arthritis Foundation guideline for the screening, monitoring, and treatment of juvenile idiopathic arthritis-associated uveitis. Arthritis Care Res. 2019;71(6):703–16.

Scott C, Chan M, Slamang W, Okong'o L, Petty R, Laxer RM, et al. Juvenile arthritis management in less resourced countries (JAMLess): consensus recommendations from the cradle of humankind. Clin Rheumatol. 2019;38(2):563–75.

Lee CU, Kim JN, Kim JW, Park SH, Lee H, Kim SK, et al. Korean rheumatology workforce from 1992 to 2015: current status and future demand. Korean J Intern Med. 2019;34(3):660–8.

Barber CE, Jewett L, Badley EM, Lacaille D, Cividino A, Ahluwalia V, et al. Stand up and be counted: measuring and mapping the rheumatology workforce in Canada. J Rheumatol. 2017;44(2):248–57.

Dolezalova P, Anton J, Avcin T, Beresford MW, Brogan PA, Constantin T, et al. The European network for care of children with paediatric rheumatic diseases: care across borders. Rheumatology (Oxford). 2019;58(7):1188–95.

Dave M, Rankin J, Pearce M, Foster HE. Global prevalence estimates of three chronic musculoskeletal conditions: club foot, juvenile idiopathic arthritis and juvenile systemic lupus erythematosus. Pediatr Rheumatol Online J. 2020;18(1):49.

Harper BD, Nganga W, Armstrong R, Forsyth KD, Ham HP, Keenan WJ, et al. Where are the paediatricians? An international survey to understand the global paediatric workforce. BMJ Paediatr Open. 2019;3(1).

Egert Y, Egert T, Costello W, Prakken BJ, Smith EMD, Wulffraat NM. Children and young people get rheumatic disease too. Lancet Child Adolesc Health. 2019;3(1):8–9.

Olaosebikan BH, Adelowo OO, Animashaun BA, Akintayo RO. Spectrum of paediatric rheumatic diseases in Nigeria. Pediatr Rheumatol Online J. 2017;15(1):7.

Foster HE, Scott C. Update the WHO EML to improve global paediatric rheumatology. Nat Rev Rheumatol. 2020;16(3):123.

Ruperto N, Garcia-Munitis P, Villa L, Pesce M, Aggarwal A, Fasth A, et al. PRINTO/PRES international website for families of children with rheumatic diseases. Ann Rheum Dis. 2005;64(7):1101–6 www.pediatric-rheumatology.printo.it.

Wulffraat NM, Vastert B, consortium S. Time to share. Pediatr Rheumatol Online J. 2013;11(1):5.

Smith N, Rapley T, Jandial S, English C, Davies B, Wyllie R, et al. Paediatric musculoskeletal matters (pmm)--collaborative development of an online evidence based interactive learning tool and information resource for education in paediatric musculoskeletal medicine. Pediatr Rheumatol Online J. 2016;14(1):1.

Foster HE, Vojinovic J, Constantin T, Martini A, Dolezalova P, Uziel Y, et al. Educational initiatives and training for paediatric rheumatology in Europe. Pediatr Rheumatol Online J. 2018;16(1):77.

Foster HE, Scott C, Tiderius CJ, Dobbs MB. The paediatric global musculoskeletal task force – ‘towards better MSK health for all’. Pediatr Rheumatol Online J. 2020;18(1):60.

Foster HE, Scott C, Tiderius CJ, Dobbs MB, Members of the Paediatric Global Musculoskeletal Task F. Improving musculoskeletal health for children and young people - A ‘call to action’. Best Pract Res Clin Rheumatol. 2020:101566.

Acknowledgements

We would like to thank all the respondents who participated in this survey and the members of the Paediatric Global Musculoskeletal Task Force to help disseminate the survey.

Funding

The study was not funded.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

HF contributed to conceptual study design, survey development, coordination of survey dissemination, writing and reviewing the manuscript. ST contributed to drafting the manuscript and prepared the figures and tables. NS contributed to survey development and design, data gathering and analysis. CS contributed to the initiation and designing of the survey, writing and reviewing the manuscript. SWT, SV, MS, TA contributed to survey development, writing and reviewing the manuscript. SC contributed to survey development, writing, reviewing manuscript and a corresponding author. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

Not applicable

Consent for publication

Not applicable

Competing interests

None of the authors have competing for interests to declare in regard to this manuscript.

Additional information

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary Information

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/. The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver (http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/) applies to the data made available in this article, unless otherwise stated in a credit line to the data.

About this article

Cite this article

Tangcheewinsirikul, S., Tang, SP., Smith, N. et al. Delivery of paediatric rheumatology care: a survey of current clinical practice in Southeast Asia and Asia-Pacific regions. Pediatr Rheumatol 19, 11 (2021). https://doi.org/10.1186/s12969-021-00498-1

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s12969-021-00498-1