Abstract

Background

Myhre syndrome is a genetic disorder caused by gain of function mutations in the SMAD Family Member 4 (SMAD4) gene, resulting in progressive, proliferative skin and organ fibrosis. Skin thickening and joint contractures are often the main presenting features of the disease and may be mistaken for juvenile scleroderma.

Case presentation

We report a case of a 13 year-old female presenting with widespread skin thickening and joint contractures from infancy. She was diagnosed with diffuse cutaneous systemic sclerosis, and treatment with corticosteroids and subcutaneous methotrexate recommended. There was however disease progression prompting genetic testing. This identified a rare heterozygous pathogenic variant c.1499 T > C (p.Ile500Thr) in the SMAD4 gene, suggesting a diagnosis of Myhre syndrome. Securing a molecular diagnosis in this case allowed the cessation of immunosuppression, thus reducing the burden of unnecessary and potentially harmful treatment, and allowing genetic counselling.

Conclusion

Myhre Syndrome is a rare genetic mimic of scleroderma that should be considered alongside several other monogenic diseases presenting with pathological fibrosis from early in life. We highlight this case to provide an overview of these genetic mimics of scleroderma, and highlight the molecular pathways that can lead to pathological fibrosis. This may provide clues to the pathogenesis of sporadic juvenile scleroderma, and could suggest novel therapeutic targets.

Similar content being viewed by others

Background

Myhre syndrome is a genetic disorder often presenting in infancy, caused by a gain of function mutation in the SMAD family member 4 (SMAD4) gene causing progressive, proliferative fibrosis, occurring spontaneously or following trauma, in addition to a unique set of clinical phenotypic features described below [1,2,3,4]. Clinical manifestations of Myhre syndrome include: cardiovascular involvement in up to 70% of patients (congenital heart defects, long- and short-segment stenosis of the aorta and peripheral arteries, pericardial effusion, constrictive pericarditis, restrictive cardiomyopathy, and arterial hypertension); respiratory manifestations (choanal stenosis, laryngotracheal narrowing, obstructive airway disease, or restrictive pulmonary disease); gastrointestinal symptoms (pyloric stenosis, duodenal strictures, severe constipation); hearing loss, mild to moderate development delay, dysmorphic features and skin involvement (skin sclerosis, particularly involving the hands and extensor surfaces) leading to joint contractures [1, 5,6,7,8,9,10,11,12]. Patients presenting with predominantly skin sclerosis and contractures, cardiovascular involvement may be misdiagnosed as a having systemic sclerosis (SSc) despite the presence of other atypical features for SSc such as hearing loss and developmental delay thus causing unnecessary exposure to immunosuppression. Herein, we present a case of a 13 year-old female considered as having diffuse cutaneous systemic sclerosis, who was subsequently identified to have Myhre syndrome caused by a previously well described heterozygous c.1499 T > C variant in SMAD4. We discuss the therapeutic implications of establishing a genetic diagnosis in this case and provide an overview of genetic mimics of scleroderma.

Case presentation

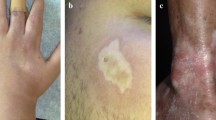

A 13 year-old girl of Black African decent was referred to the scleroderma services of the rheumatology department at Great Ormond Street Hospital for Children NHS Foundation Trust, London for a second opinion with history of extensive skin thickening and widespread joint contractures, which started in infancy at the age of 9 months (Fig. 1). The skin changes started in her lower limps and over the course of 2 years spread to the arms and trunk. The joint contractures were noted approximately 2 years after the initial skin changes were observed. There was history suggestive of mild Raynaud’s phenomenon, but no digital ulceration, gastrointestinal, or respiratory symptoms of note. She was born at term with no neonatal complications. She had a past medical history of: valvar and supravalvar pulmonary artery stenosis requiring serial balloon dilatation; mild developmental delay; and conductive hearing loss. Microarray-based comparative genomic hybridization was used to exclude chromosomal abnormalities that could explain her presentation and was normal. There was no history of cancer in the immediate family.

Clinical examination revealed diffusely thickened skin affecting the full length of her limbs and trunk, but sparing her face; weight 41 kg (25th centile for age), height 139 cm (2nd centile for age). She was normotensive at time of review. Delayed puberty was noted and the patient had no menarche at the age of 13 years old. There were multiple joint contractures, but no active arthritis. Cutaneous telangiectasia, fingertip ulceration and calcinosis were absent. She was also noted to have mild dysmorphic features: small eyes and ears, a broad nasal tip, a long and prominent chin, bilateral clinodactyly and mild two-three toe syndactyly. Nailfold capillaroscopy was abnormal, with evidence of dilated capillary loops, tortuosity, micro-bleeding, and widespread dropout in a pattern compatible with scleroderma-spectrum connective tissue disease (Fig. 2). Digital thermography demonstrated cold baseline cutaneous temperature of the peripheries, with some of the fingers remaining cool long after cold challenge. She tested weakly positive for antinuclear antibodies (ANA at 1:160, homogenous pattern); negative for dsDNA antibodies, rheumatoid factor and extranuclear antibodies. Complement function (alternate and classical pathways) was normal, as were levels of C3, C4, and C1q. Erythrocyte sedimentation rate and C-reactive protein were repeatedly within normal limits. Echocardiography revealed mild persistent pulmonary stenosis, a small left pulmonary artery, mild coarctation of the aorta, mild biventricular hypertrophy, but no evidence of pulmonary hypertension. Barium swallow was normal. A skeletal survey revealed advanced bone age, but no evidence of skeletal dysplasia. A skin biopsy was performed, with histology revealing hyperkeratotic epidermis, and fibrotic dermis with areas of hyalinization; adnexal structures were sparse with absence of pilosebaceous units (Fig. 3). These histological features are typically encountered in scleroderma histopathology with the exception of the hyperkeratotic epidermis, which is less often seen [11, 13, 14]. She was diagnosed with diffuse cutaneous systemic sclerosis, and treatment with oral prednisolone 2 mg/kg/day for 6 weeks, and subcutaneous methotrexate (15 mg/m2/week) started. There was deterioration in joint contractures (further loss of range of movement) and spreading of skin changes observed despite treatment. When reviewed for a second opinion at GOSH, a genetic diagnosis was suspected and genetic testing via Sanger sequencing was undertaken for some conditions that cause skin thickening, dysmorphic features and congenital heart disease. Genetic testing revealed a previously well described rare heterozygous c.1499 T > C (p.lle500Thr) class 5 variant in SMAD4 [12], suggesting a diagnosis of Myhre syndrome. Testing for variants in other relevant genes pertinent to phenotype (including PTPN11, LMNA, and MMP14) revealed no other pathogenic variants [15,16,17,18,19,20,21,22,23,24,25,26]. Parental testing confirmed this variant arose de novo in the proband. All immunosuppression was subsequently stopped, genetic counselling was provided, and the prognosis of Myhre syndrome was discussed with the patient and family.

Skin histology of the 13 year old patient with Myhre syndrome mimicking juvenile scleroderma we describe in this report. a-b Photomicrographs of skin punch biopsy containing epidermis, dermis and superficial subcutis. There is no significant lichenoid reaction or inflammatory infiltrate (L) but the dermis shows marked replacement by hypocellular, hyalinised areas of bland collagen(R). There are no other specific features and the adnexal structures remain in this biopsy. (H&E, original magnifications Lx40 and Rx100)

Discussion

We present the case of a 13 year-old with a scleroderma-like condition, ultimately diagnosed with Myhre syndrome, a genetic disorder that may mimic juvenile scleroderma (Supplemental Table 1). Securing a molecular diagnosis in this case allowed the cessation of immunosuppression thus reducing the burden of unnecessary toxic exposure to glucocorticoids, and other ineffective immunosuppressive treatments; and facilitated genetic counselling, and prognostication. This also had implications for long term follow up as patients with Myhre syndrome require close surveillance for detection of any malignancy in view of increased risk of cancer reported in these patients [5, 12, 27]. We therefore highlight this case to raise awareness of a growing number of monogenic fibrotic disorders mimicking juvenile scleroderma which need to be considered in patients with cutaneous fibrosis beginning early in life (Table 1).

Myhre syndrome is caused by mutations in SMAD encoding for SMAD4 protein, a transducer mediating transforming growth factor β (TGF-β) signalling [2,3,4]. Skin fibroblasts from patients with Myhre syndrome show increased SMAD4 expression, impaired matrix deposition, and altered expression of genes encoding matrix metalloproteinases and related inhibitors. Losartan, an angiotensin-II type 1 receptor blocker but also a (lesser-known) TGF-β antagonist has been shown in vitro to normalize metalloproteinase and related inhibitor transcript levels, and to correct the extracellular matrix (ECM) deposition defect in fibroblasts from these patients [30]. Some patients with aortic pathology associated with Myhre syndrome have already been treated with losartan, with reports of stabilisation of their vasculopathy; but the effect on skin fibrosis has never been described [30,31,32,33,34]. We suggest that further studies could explore losartan (or other therapies acting on the SMAD4 pathway) as a potential targeted therapeutic option for cutaneous fibrosis associated with this rare genetic disease. At the time of writing this report losartan therapy is being considered for the patient described herein.

Several other conditions may also mimic juvenile scleroderma (Table 1). Skin thickening is common to all of these disorders, and may be localized (morphoea-like), or widespread (like diffuse scleroderma) [35,36,37,38,39,40,41,42,43,44,45]. Vasculopathy is frequently observed and should be actively screened for. We highlight for the first time in this case the abnormal nailfold capillaroscopy with similar findings to those observed in SSc. Degenerative cardiac or pulmonary manifestations may also exhibit a secondary inflammatory component, thus posing considerable diagnostic challenges and making it more likely that such patients could be exposed to ineffective but toxic immunosuppression, as illustrated by our case [1, 2, 4, 46,47,48,49]. On occasions, autoimmunity has also been described [50,51,52,53]. The management and long term outcome of these genetic scleroderma mimics is, however, entirely different and immunosuppression may not be required or may in fact be harmful in some cases [54, 55]. We therefore suggest that genetic testing should be considered in all patients with sclerodermatous skin disease of very young onset (infancy) and recommend screening for vasculopathy (including congenital heart disease and aortopathy) with echocardiography, and non-invasive angiography. Genetic screening for monogenic diseases should also be considered in older patients with scleroderma with atypical clinical course; and in those not responding to conventional immunosuppression.

Regarding the methodology of genetic screening, our case again illustrates the importance of next-generation sequencing (NGS) methodologies in this context. Mainly due to lack of routine NGS methods, initial routine genetic testing of candidate genes by Sanger was performed for this patient. This was a time consuming, costly, and mainly “clinician best guess” driven approach, which resulted in diagnostic delay of several months. Whole exome and genome sequencing and targeted gene panels now allow rapid, simultaneous detection of multiple genes, and are increasingly being used as diagnostic tools and to explore the pathogenesis of monogenic diseases [56,57,58,59,60,61]. These techniques are particularly useful for screening diseases with overlapping phenotypes. For instance, we (and many others) have used NGS to extensively study monogenic systemic inflammation, with significant diagnostic and therapeutic impact [60, 61]. Similarly, we anticipate that application of NGS genetic screening to cohorts of patients with juvenile scleroderma (in all its forms) may identify a proportion with monogenic disease, and that evidence of tissue inflammation and autoimmunity should not preclude the possibility of a genetic diagnosis for the reasons discussed above.

Understanding the genetic basis of these genetic diseases with sclerodermatous features is not only crucial to secure diagnoses, improve prognostication and to facilitate genetic counselling but may also provide clues to the pathogenesis of sporadic cases. For instance, several of the genetic mimics of scleroderma involve the TGF-β pathway [2, 62,63,64]. At the cellular level, TGF-β plays potent roles in proliferation, differentiation and apoptosis of many cell types, and therefore unsurprisingly germline mutations in the TGF-β signalling pathway cause various phenotypes affecting the skeletal, muscular, and/or cardiovascular systems [2, 62,63,64,65]. TGF-β has also been identified as a regulator of pathological fibrogenesis in juvenile and adult onset systemic sclerosis [64,65,66,67,68]. A wide range of drugs targeting the TGF-β signalling pathways are now available [69,70,71,72,73], and need to be tested for their ability to modulate the phenotypes of both these inherited scleroderma mimics but possibly also for efficacy in addition to anti-inflammatory medication in sporadic systemic sclerosis, given their overlapping pathomechanisms.

Conclusion

Myhre syndrome is a rare genetic disorder that causes skin thickening and joint contractures, and may be misdiagnosed as juvenile scleroderma (systemic sclerosis). Many other genetic conditions can similarly mimic the clinical manifestations of juvenile scleroderma and should be considered in the differential diagnosis of juvenile scleroderma. Onset in infancy and comorbidities such as structural heart disease, large vessel vasculopathy, dysmorphic features, developmental delay, and hearing loss are important clues to a genetic diagnosis. Clinical application of NGS is likely to transform the genetic diagnostic approach to young patients with scleroderma-like diseases and suggest targeted therapies for some cases. Therapeutic targets for sporadic cases of juvenile scleroderma are also likely to emerge, given the overlapping disease mechanisms for all these conditions leading to vasculopathy, skin and organ fibrosis.

Availability of data and materials

Data sharing is not applicable to this article as no datasets were generated or analysed.

Abbreviations

- ANA:

-

Anti-nuclear antibodies

- ECM:

-

Extracellular Matrix

- dsDNA:

-

Double-stranded DNA

- NGS:

-

Next generation sequencing

- SSc:

-

Systemic sclerosis

- TGF-β:

-

Transforming growth factor type beta

References

Myhre SA, Ruvalcaba RH, Graham CB. A new growth deficiency syndrome. Clin Genet. 1981;20(1):1–5.

Le Goff C, Mahaut C, Abhyankar A, Le Goff W, Serre V, Afenjar A, et al. Mutations at a single codon in mad homology 2 domain of SMAD4 cause Myhre syndrome. Nat Genet. 2012 Jan;44(1):85–8.

Caputo V, Bocchinfuso G, Castori M, Traversa A, Pizzuti A, Stella L, et al. Novel SMAD4 mutation causing Myhre syndrome. Am J Med Genet A. 2014 Jul;164(7):1835–40.

Caputo V, Cianetti L, Niceta M, Carta C, Ciolfi A, Bocchinfuso G, et al. A restricted spectrum of mutations in the SMAD4 tumor-suppressor gene underlies Myhre syndrome. Am J Hum Genet. 2012 Jan;90(1):161–9.

Lin AE, Michot C, Cormier-Daire V, L’Ecuyer TJ, Matherne GP, Barnes BH, et al. Gain-of-function mutations in SMAD4 cause a distinctive repertoire of cardiovascular phenotypes in patients with Myhre syndrome. Am J Med Genet A. 2016;170(10):2617–31.

Garavelli L, Maini I, Baccilieri F, Ivanovski I, Pollazzon M, Rosato S, et al. Natural history and life-threatening complications in Myhre syndrome and review of the literature. Eur J Pediatr. 2016;175(10):1307–15.

Starr LJ, Grange DK, Delaney JW, Yetman AT, Hammel JM, Sanmann JN, et al. Myhre syndrome: clinical features and restrictive cardiopulmonary complications. Am J Med Genet A. 2015;167(12):2893–901.

McGowan R, Gulati R, McHenry P, Cooke A, Butler S, Keng WT, et al. Clinical features and respiratory complications in Myhre syndrome. Eur J Med Genet. 2011;54(6):e553–9.

Michot C, Le Goff C, Mahaut C, Afenjar A, Brooks AS, Campeau PM, et al. Myhre and LAPS syndromes: clinical and molecular review of 32 patients. Eur J Hum Genet. 2014;22(11):1272–7.

van Steensel MAM, Vreeburg M, Steijlen PM, de Die-Smulders C. Myhre syndrome in a female with previously undescribed symptoms: further delineation of the phenotype. Am J Med Genet A. 2005;139A(2):127–30.

Titomanlio L, Marzano MG, Rossi E, D’armiento M, De Brasi D, Vega GR, et al. Case of Myhre syndrome with autism and peculiar skin histological findings. Am J Med Genet. 2001;103(2):163–5.

Starr LJ, Lindor NM, Lin AE. Myhre syndrome. In: GeneReviews®. Seattle: University of Washington; 2017.

Torres JE, Sánchez JL. Histopathologic differentiation between localized and systemic scleroderma. Am J Dermatopathol. 1998;20(3):242–5.

McNiff JM, Glusac EJ, Lazova RZ, Carroll CB. Morphea limited to the superficial reticular dermis: an underrecognized histologic phenomenon. Am J Dermatopathol. 1999;21(4):315–9.

Tartaglia M, Mehler EL, Goldberg R, Zampino G, Brunner HG, Kremer H, et al. Mutations in PTPN11, encoding the protein tyrosine phosphatase SHP-2, cause Noonan syndrome. Nat Genet. 2001;29(4):465–8.

Allanson JE. Noonan syndrome. J Med Genet. 1987;24(1):9–13.

Sharland M, Burch M, McKenna WM, Paton MA. A clinical study of Noonan syndrome. Arch Dis Child. 1992;67(2):178–83.

Sznajer Y, Keren B, Baumann C, Pereira S, Alberti C, Elion J, et al. The spectrum of cardiac anomalies in Noonan syndrome as a result of mutations in the PTPN11 gene. Pediatrics. 2007;119(6):e1325–31.

Ferrero GB, Baldassarre G, Delmonaco AG, Biamino E, Banaudi E, Carta C, et al. Clinical and molecular characterization of 40 patients with Noonan syndrome. Eur J Med Genet. 2008;51(6):566–72.

DeBusk FL. The Hutchinson-Gilford progeria syndrome: report of 4 cases and review of the literature. J Pediatr. 1972;80(4):697–724.

Eriksson M, Brown WT, Gordon LB, Glynn MW, Singer J, Scott L, et al. Recurrent de novo point mutations in Lamin a cause Hutchinson–Gilford progeria syndrome. Nature. 2003;423(6937):293–8.

Cao H, Hegele RA. LMNA is mutated in Hutchinson-Gilford progeria (MIM 176670) but not in Wiedemann-Rautenstrauch progeroid syndrome (MIM 264090). J Hum Genet. 2003;48(5):271–4.

Winchester P, Grossman H, Lim WN, Danes BS. A new acid mucopolysaccharidosis with skeletal deformities simulating rheumatoid arthritis. Am J Roentgenol. 1969;106(1):121–8.

Hollister DW, Rimoin DL, Lachman RS, Cohen AH, Reed WB, Westin GW. The Winchester syndrome: a nonlysosomal connective tissue disease. J Pediatr. 1974;84(5):701–9.

Prapanpoch S, Jorgenson RJ, Langlais RP, Nummikoski PV. Winchester syndrome: a case report and literature review. Oral Surg Oral Med Oral Pathol Oral Radiol. 1992;74(5):671–7.

Evans BR, Mosig RA, Lobl M, Martignetti CR, Camacho C, Grum-Tokars V, et al. Mutation of membrane Type-1 metalloproteinase, MT1-MMP, causes the multicentric Osteolysis and arthritis disease Winchester syndrome. Am J Hum Genet. 2012;91(3):572–6.

Lin AE, Alali A, Starr LJ, Shah N, Beavis A, Pereira EM, et al. Gain-of-function pathogenic variants in SMAD4 are associated with neoplasia in Myhre syndrome. Am J Med Genet A. 2020;182(2):328–37.

Online Mendelian Inheritance in Man Database, OMIM®. McKusick-Nathans Institute of Genetic Medicine, Johns Hopkins University (Baltimore, MD).. Available from: https://omim.org/. [cited 2019 Jun 4].

Genetics Home Reference Database. National Library of Medicine (US). Bethesda (MD). Available from: https://ghr.nlm.nih.gov/. [cited 2019 Jun 4].

Piccolo P, Mithbaokar P, Sabatino V, Tolmie J, Melis D, Schiaffino MC, et al. SMAD4 mutations causing Myhre syndrome result in disorganization of extracellular matrix improved by losartan. Eur J Hum Genet. 2014;22(8):988–94.

Brooke BS, Habashi JP, Judge DP, Patel N, Loeys B, Dietz HC III. Angiotensin II blockade and aortic-root dilation in Marfan’s syndrome. N Engl J Med. 2008;358(26):2787–95.

Groenink M, den Hartog AW, Franken R, Radonic T, de Waard V, Timmermans J, et al. Losartan reduces aortic dilatation rate in adults with Marfan syndrome: a randomized controlled trial. Eur Heart J. 2013;34(45):3491–500.

Araujo AQ, Arteaga E, Ianni BM, Buck PC, Rabello R, Mady C. Effect of losartan on left ventricular diastolic function in patients with nonobstructive hypertrophic cardiomyopathy. Am J Cardiol. 2005;96(11):1563–7.

Shimada YJ, Passeri JJ, Baggish AL, O’Callaghan C, Lowry PA, Yannekis G, et al. Effects of losartan on left ventricular hypertrophy and fibrosis in patients with nonobstructive hypertrophic cardiomyopathy. JACC Heart Fail. 2013;1(6):480–7.

Merideth MA, Gordon LB, Clauss S, Sachdev V, Smith AC, Perry MB, et al. Phenotype and course of Hutchinson–Gilford progeria syndrome. N Engl J Med. 2008;358(6):592–604.

Rork JF, Huang JT, Gordon LB, Kleinman M, Kieran MW, Liang MG. Initial cutaneous manifestations of Hutchinson-Gilford Progeria syndrome. Pediatr Dermatol. 2014;31(2):196–202.

Huang S, Lee L, Hanson NB, Lenaerts C, Hoehn H, Poot M, et al. The spectrum of WRN mutations in Werner syndrome patients. Hum Mutat. 2006;27(6):558–67.

Gonullu E, Bilge NŞY, Kaşifoğlu T, Korkmaz C. Werner’s syndrome may be lost in the shadow of the scleroderma. Rheumatol Int. 2013;33(5):1309–12.

Wang LL, Levy ML, Lewis RA, Chintagumpala MM, Lev D, Rogers M, et al. Clinical manifestations in a cohort of 41 Rothmund-Thomson syndrome patients. Am J Med Genet. 2001;102(1):11–7.

Shastry S, Simha V, Godbole K, Sbraccia P, Melancon S, Yajnik CS, et al. A novel syndrome of mandibular hypoplasia, deafness, and progeroid features associated with lipodystrophy, undescended testes, and male hypogonadism. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2010;95(10):E192–7.

Senniappan S, Hughes M, Shah P, Shah V, Kaski JP, Brogan P, et al. Pigmentary hypertrichosis and non-autoimmune insulin-dependent diabetes mellitus (PHID) syndrome is associated with severe chronic inflammation and cardiomyopathy, and represents a new monogenic autoinflammatory syndrome. J Pediatr Endocrinol Metab. 2013;26(9–10):877–82.

Freyschmidt J. Melorheostosis: a review of 23 cases. Eur Radiol. 2001;11(3):474–9.

Ehrig T, Cockerell CJ. Buschke-ollendorff syndrome: report of a case and interpretation of the clinical phenotype as a type 2 segmental manifestation of an autosomal dominant skin disease. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2003;49(6):1163–6.

Liu T, McCalmont TH, Frieden IJ, Williams ML, Connolly MK, Gilliam AE. The stiff skin syndrome: case series, differential diagnosis of the stiff skin phenotype, and review of the literature. Arch Dermatol. 2008;144(10):1351–9.

Muñoz-Santos C, Guilabert A, Moreno N, To-Figueras J, Badenas C, Darwich E, et al. Familial and sporadic Porphyria Cutanea Tarda: clinical and biochemical features and risk factors in 152 patients. Medicine (Baltimore). 2010;89(2):69–74.

Tyndall AJ, Bannert B, Vonk M, Airo P, Cozzi F, Carreira PE, et al. Causes and risk factors for death in systemic sclerosis: a study from the EULAR scleroderma trials and research (EUSTAR) database. Ann Rheum Dis. 2010;69(10):1809–15.

Rubio-Rivas M, Royo C, Simeón CP, Corbella X, Fonollosa V. Mortality and survival in systemic sclerosis: systematic review and meta-analysis. Semin Arthritis Rheum. 2014;44(2):208–19.

Steen VD, Medsger TA. Changes in causes of death in systemic sclerosis, 1972-2002. Ann Rheum Dis. 2007;66(7):940–4.

Aviña-Zubieta JA, Man A, Yurkovich M, Huang K, Sayre EC, Choi HK. Early cardiovascular disease after the diagnosis of systemic sclerosis. Am J Med. 2016;129(3):324–31.

Yan X, Jin J. Primary cutaneous amyloidosis associated with autoimmune hepatitis-primary biliary cirrhosis overlap syndrome and Sjögren syndrome: A case report. Medicine (Baltimore). 2018;97(8):e0004.

Kogure A, Ohshima Y, Watanabe N, Ohba T, Miyata M, Ohara M, et al. A case of Werner’s syndrome associated with systemic lupus erythematosus. Clin Rheumatol. 1995;14(2):199–203.

Fritsch S, Wojcik AS, Schade L, Machota MM, Brenner FM, Paiva ES. Increased photosensitivity? Case report of porphyria cutanea tarda associated with systemic lupus erythematosus. Rev Bras Reum. 2012;52(6):965–70.

Kostik MM, Chikova IA, Avramenko VV, Vasyakina LI, Le Trionnaire E, Chasnyk VG, et al. Farber lipogranulomatosis with predominant joint involvement mimicking juvenile idiopathic arthritis. J Inherit Metab Dis. 2013;36(6):1079–80.

Orteu CH, Ong VH, Denton CP. Scleroderma mimics – clinical features and management. Best Pract Res Clin Rheumatol. 2020;p101489.

Foti R, Leonardi R, Rondinone R, Di Gangi M, Leonetti C, Canova M, et al. Scleroderma-like disorders. Autoimmun Rev. 2008;7(4):331–9.

Rusmini M, Federici S, Caroli F, Grossi A, Baldi M, Obici L, et al. Next-generation sequencing and its initial applications for molecular diagnosis of systemic auto-inflammatory diseases. Ann Rheum Dis. 2016;75(8):1550–7.

Ortega-Moreno L, Giráldez BG, Soto-Insuga V, Losada-Del Pozo R, Rodrigo-Moreno M, Alarcón-Morcillo C, et al. Molecular diagnosis of patients with epilepsy and developmental delay using a customized panel of epilepsy genes. PLoS One. 2017;12(11):e0188978.

Nijman IJ, van Montfrans JM, Hoogstraat M, Boes ML, van de Corput L, Renner ED, et al. Targeted next-generation sequencing: A novel diagnostic tool for primary immunodeficiencies. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2014;133(2):529–534.e1.

Mak ACY, Tang PLF, Cleveland C, Smith MH, Kari Connolly M, Katsumoto TR, et al. Brief report: whole-exome sequencing for identification of potential causal variants for diffuse cutaneous systemic sclerosis. Arthritis Rheumatol. 2016;68(9):2257–62.

McCreary D, Omoyinmi E, Hong Y, Mulhern C, Papadopoulou C, Casimir M, et al. Development and validation of a targeted next-generation sequencing gene panel for children with neuroinflammation. JAMA Netw Open. 2019;2(10):e1914274.

Omoyinmi E, Standing A, Keylock A, Price-Kuehne F, Gomes SM, Rowczenio D, et al. Clinical impact of a targeted next-generation sequencing gene panel for autoinflammation and vasculitis. PLoS One. 2017;12(7):e0181874.

Le Goff C, Morice-Picard F, Dagoneau N, Wang LW, Perrot C, Crow YJ, et al. ADAMTSL2 mutations in geleophysic dysplasia demonstrate a role for ADAMTS-like proteins in TGF-β bioavailability regulation. Nat Genet. 2008;40(9):1119–23.

Loeys BL, Gerber EE, Riegert-Johnson D, Iqbal S, Whiteman P, McConnell V, et al. Mutations in fibrillin-1 cause congenital scleroderma: stiff skin syndrome. Sci Transl Med. 2010;2(23):23ra20.

Bader-Meunier B, Bonafé L, Fraitag S, Breton S, Bodemer C, Baujat G. Mutation in MMP2 gene may result in scleroderma-like skin thickening. Ann Rheum Dis. 2016;75(1):e1.

Mori Y, Chen S-J, Varga J. Expression and regulation of intracellular SMAD signaling in scleroderma skin fibroblasts. Arthritis Rheum. 2003;48(7):1964–78.

Kawakami T, Ihn H, Xu W, Smith E, LeRoy C, Trojanowska M. Increased expression of TGF-β receptors by scleroderma fibroblasts: evidence for contribution of autocrine TGF-β signaling to scleroderma phenotype. J Invest Dermatol. 1998;110(1):47–51.

Kubo M, Ihn H, Yamane K, Tamaki K. Up-regulated expression of transforming growth factor β receptors in dermal fibroblasts in skin sections from patients with localized scleroderma. Arthritis Rheum. 2001;44(3):731–4.

Sargent JL, Milano A, Bhattacharyya S, Varga J, Connolly MK, Chang HY, et al. A TGFβ-responsive gene signature is associated with a subset of diffuse scleroderma with increased disease severity. J Invest Dermatol. 2010;130(3):694–705.

Mead AL, Wong TTL, Cordeiro MF, Anderson IK, Khaw PT. Evaluation of anti-TGF-β2 antibody as a new postoperative anti-scarring agent in glaucoma surgery. Investig Opthalmol Vis Sci. 2003;44(8):3394–401.

Lim D-S, Lutucuta S, Bachireddy P, Youker K, Evans A, Entman M, et al. Angiotensin II blockade reverses myocardial fibrosis in a transgenic mouse model of human hypertrophic cardiomyopathy. Circulation. 2001;103(6):789–91.

Yamada H, Tajima S, Nishikawa T. Tranilast inhibits collagen synthesis in normal, scleroderma and keloid fibroblasts at a late passage culture but not at an early passage culture. J Dermatol Sci. 1995;9(1):45–7.

Soria A, Cario-André M, Lepreux S, Rezvani HR, Pasquet JM, Pain C, et al. The effect of Imatinib (Glivec®) on scleroderma and normal dermal fibroblasts: a preclinical study. Dermatology. 2008;216(2):109–17.

Pannu J, Asano Y, Nakerakanti S, Smith E, Jablonska S, Blaszczyk M, et al. Smad1 pathway is activated in systemic sclerosis fibroblasts and is targeted by imatinib mesylate. Arthritis Rheum. 2008;58(8):2528–37.

Acknowledgments

Dr. Eleftheriou, Professor Sebire and Professor Brogan acknowledge the National Institute of Health Research (NIHR) Biomedical Research Centre at GOSH.

Disclaimer

The views expressed are those of the authors and not necessarily those of the NHS, NIHR, or Department of Health.

Funding

No funding sources. Dr. Jensen was supported by GOSH Children’s Charity Grant (CP_RSRCH_003) and Rosetrees Trust Grant (A2584) Dr. Eleftheriou and Dr. Hong were supported by Versus Arthritis (grants 20164, 21593, and 21791). Professor Brogan is supported by the Great Ormond Street Hospital (GOSH) Children’s Charity.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

BJ, RJ, PB and DE conceived the study, obtained and analysed data and drafted the manuscript. YH, EO, CP, NS and KH obtained and analysed data and drafted the manuscript. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

Formal written consent for publication was obtained from the patient’s mother and is available on request.

Consent for publication

Formal written consent for publication was obtained from the patient’s mother.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary information

Additional file 1 Supplemental Table

1. Features of juvenile localised scleroderma, juvenile systemic sclerosis and Myhre syndrome.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/. The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver (http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/) applies to the data made available in this article, unless otherwise stated in a credit line to the data.

About this article

Cite this article

Jensen, B., James, R., Hong, Y. et al. A case of Myhre syndrome mimicking juvenile scleroderma. Pediatr Rheumatol 18, 72 (2020). https://doi.org/10.1186/s12969-020-00466-1

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s12969-020-00466-1