Abstract

Background

Involving people of all ages in health research is now widely advocated. To date, no studies have explored whether and how young people with chronic rheumatic conditions want to be involved in influencing health research. This study aimed to explore amongst young people with rheumatic conditions, 1) their experiences of research participation and involvement 2) their beliefs about research involvement and 3) beliefs about how young people’s involvement should be organized in the future.

Methods

Focus groups discussions with young people aged 11–24 years with rheumatic conditions across the UK. Data was analysed using a qualitative Framework approach.

Results

Thirteen focus groups were held involving 63 participants (45 F: 18 M, mean age 16, range 10 to 24 years) across the UK. All believed that young people had a right to be involved in influencing research and to be consulted by researchers. However, experience of research involvement varied greatly. For many, the current project was the first time they had been involved. Amongst those with experience of research involvement, awareness of what they had been involved in and why was often low. Those who had previously participated in research appeared more positive and confident about influencing research in the future. However, all felt that there were limited opportunities for them to be both research participants and to get involved in research as public contributors.

Conclusions

These findings suggest that there is an on-going need to both increase awareness of research involvement and participation of young people in rheumatology as well as amongst young people themselves.

Similar content being viewed by others

Explore related subjects

Find the latest articles, discoveries, and news in related topics.Background

Involving people at all stages of health research (including young people) is now widely recommended [1]. In the UK, many grant and all ethics application processes now ensure that patient and public involvement (PPI) in research is embedded within them [2]. PPI is also advocated by professional bodies in general and specifically for young people. [3, 4].

Within this study we defined involvement as “where members of the public are actively involved in research projects and in research organisations” [5] and participation as, “where patients and the public act as research participants”.

Involving patients and the public in research helps ensure that research is designed around their needs and what is important to them [6]. However, it can be challenging to involve a diverse range of people [7]. This is particularly true with young people [8]. In view of the major sociocultural influences on adolescent health [9], representative sampling (in terms of socio-demographics- gender, ethnicity, culture and urban vs rural regional variations) is vital in studies of adolescents in general and when not feasible, the limitations of non-representative samples should be stated. In view of the wide variation of normal puberty, chronological age is a poor indicator of developmental status. Therefore, attention to the stages of adolescent development is required in any research involving young people. Ensuring such diversity may also result in part from a lack of confidence and/or inexperience amongst researchers regarding PPI [10], particularly with respect to young people in these particular developmental stages as although clinical research focusing on young people is rapidly evolving, it is still developing compared to research with adult populations [11].

The Barbara Ansell National Network for Adolescent Rheumatology (BANNAR) is a network of rheumatology professionals aiming to ensure that young people in the UK have the best chance to benefit from developments in the field of adolescent and young adult rheumatology [12]. A key priority for BANNAR is to involve young people in developing the network’s research priorities.

This study aimed to explore (i) experiences of research participation and involvement (ii) beliefs about research involvement amongst young people with rheumatic conditions and (iii) beliefs about how young people’s involvement should be organized in the future.

Data regarding their research priorities has been published elsewhere [13].

Methods

This was a qualitative study of young people with rheumatic conditions. Sixteen focus groups were planned (8 with 11–15 year olds and 8 with 16–24 year olds) in all four nations of the UK to capture the potential impact of differences in health service organisation on young people’s experiences. The age ranges were chosen to reflect adolescent developmental stages i.e. early and mid-adolescence (11–15 years) and late adolescence and young adulthood (16–24 years).. Sixteen focus groups were conducted in all four nations of the UK to capture the potential impact of differences in health service organisation on young people’s experiences. The methods for this project have already been reported in detail elsewhere [13, 14].

Recruitment

Rheumatology team members gave study information sheets to a broad range of eligible young people (in terms of age, gender, ethnicity, condition, research experience and socio-economic status). Inclusion criteria were English speaking 11–24 year olds, under the care of a rheumatologist with any chronic rheumatic condition.

Young people were also recruited via a UK based charity, Arthritis Care to ensure that young people who were not under the care of rheumatologists associated with BANNAR were involved [15]. As the aim of the project was to obtain the views from young people with any chronic rheumatic condition ie not specific to any particular disease, the only demographic details collected on individual participants were gender and age.

Focus groups were moderated by SP (a social scientist) and/or JMcD (a Paediatric Rheumatologist) who had no direct involvement in the clinical care of participants.

Focus group topic guide

The topic guide is described in detail elsewhere [14]. Focus groups lasted for up to 90 min and explored:

-

1.

Experiences of research participation and involvement

-

2.

Beliefs about the research process and young people’s involvement in it

-

3.

Beliefs about how young people’s involvement should be organised in the future

Data management

Focus group recordings were transcribed verbatim, and pseudonyms were created for names, organisations and places.

The data was analysed thematically, using the Framework approach to qualitative data analysis [16]. Framework allowed both apriori and emergent themes to be included within the analysis. The study topic guide was used as a starting point for the thematic framework, and then SP, KC and JM read through the transcripts and identified recurrent themes to further develop the framework. This framework was then applied to the data and further refined where necessary.

Results

Thirteen focus groups were held across the UK (England 8; Scotland 2; Northern Ireland 2; Wales 1). The original aim had been to conduct 16 focus groups but data saturation was achieved after 11. We determined that no new ideas were generated via reviewing recordings and transcripts and early analyses of the data. We however conducted a further 2 focus groups to ensure that young people from all four nations of the UK had the opportunity to participate although no new ideas were identified in this groups.

Six groups were held with 11–15 year olds (n = 30) and seven with 16–24 year olds (n = 33). Participants’ ages ranged from 11 to 24 years (mean = 16), 20 of whom were male and 43 female. Characteristics of participants are detailed in Table 1.

The themes which were identified are detailed in Table 2.

Young people’s experiences of research participation

Young people’s experience and understanding of research varied greatly. For example, some knew that they had been a research participant but could not recall the details of the research (Table 3a). This was due, in part, to the challenges of recalling childhood experiences when older (Table 3b) Some explained that their younger selves had been happy to leave the responsibility for understanding the details of the research to their parents. (Table 3c).

Some participants however had clear memories of the research with a number expressing concern about the lack of feedback they had received on findings (Table 3d, e and f). Others spoke about the importance of clearly understanding what they were contributing to the research (Table 3g).

For some young people, altruism was a key reason for their participation, as they believed that taking part was the ‘right thing to do’ and that it would be impossible for young people in their position in the future to be helped if they did not participate (Table 3h, i, j and k).

Finally, a considerable number of participants reported being interested in research participation but could not recall ever being asked to take part in clinical research until the reported study.

Beliefs about and experiences of, young people being involved in research

Young people believed that they offered a valuable, different perspective on the research process compared to adults (including researchers) (Table 4a and c). They felt that contributing the lived experience of their condition to the research process was valuable and essential, as many had significant experience of their illness and its treatment since disease onset in early childhood (Table 4c, d, e and f).

Experience of research involvement varied from considerable to no experience (Table 4g, h, i, j and k). Several reported prior involvement in advisory groups although they varied in their perceptions of the value of their contribution to such groups (Table 4h, I, j and k). As with research participation, altruism was a key driver for young people to become involved in shaping research (Table 4b ).

Challenges to and facilitators of, young people’s involvement

All participants were able to discuss their beliefs on the best approaches to involving young people in research (Table 5a-f) even if they had no prior experience. They stressed the importance of co-production of research with researchers and believed that involvement should be driven and organised by public contributors when possible (Table 5d). Participants advocated using both online and face to face approaches to involvement in addition to gaining a greater understanding of young people’s networks to facilitate their involvement (Table 5a, b and c). The use of social media was believed to be a key approach to facilitate the involvement of a wide range of young people in research (Table 5a).

Despite feeling that young people had a right to be involved, participants expressed uncertainty over the mechanisms by which young people could be involved in research and how this can best be supported (Table 4e). All believed that accessing information about research and research findings was challenging to both research participation and involvement (Table 5e).

Practical considerations when involving young people in research

Timing of involvement opportunities was a key issue, with young people discussing the importance of their personal commitments being considered when involvement requests were made (Table 6a, b and c). They also discussed the importance of researchers not asking recently diagnosed young people to be involved as they felt that at this time, young people would have too much to do to become familiar with their condition before they could consider research involvement (Table 6c). A further suggestion was for researchers to combine involvement with other activities young people are already doing (Table 6d).

Young people discussed how offering compensation could influence the types of people who became involved. Some felt that offering compensation could lead to people becoming involved who did not feel strongly about the research, and others that it would facilitate a wider range of people considering involvement (Table 6e).

Young people also had views regarding how involvement should be organised with some specifically advocating facilitation but that this ideally should be “patient-led” (Table 6f and g).

Discussion

To the best of our knowledge, this is the first study, to explore the experiences and beliefs of young people with rheumatic conditions about research involvement. Although young people felt that they had a right to be involved in research, experience of research involvement varied. This may reflect geographical variation in the research culture, i.e. the extent to which research participation and involvement of people in research were viewed as priorities and key elements of usual care by clinicians, researchers and their host institutions.

Young people also expressed a wish to increase their research awareness. This may have arisen in part due to difficulties in remembering whether they had taken part in research especially if what was involved was similar to usual care e.g. completing the Childhood Assessment Questionnaire [17].

If young people believe that they have a low awareness of research in general, then it is also likely to be difficult to increase their involvement as a public contributor. In this study some young people reported never being approached about research participation nor research involvement. This concurs with the findings of a previous UK audit of paediatric and adolescent rheumatology services which reported that at least 60% of centres did not involve young people in research other than as research participants [14].

An interesting finding was that some young people who had actually been involved in shaping research did not always perceive this as involvement. One explanation for this may be the lack of feedback they received following their involvement, or it may reflect lack of clarity of their role during the participation and involvement processes.

A key strength of this study was the inclusion of 63 young people from a broad range of ages and from all four UK nations, thereby reflecting a range of service provision and research opportunities. The variation in the experiences of research involvement and participation was an important finding, validating our approach and highlighting the need to conduct a national study. However, recruitment for this study was poor in some areas particularly if there was not a PPI or transition coordinator who could help with recruitment. In the development phase of this research, a survey of the 25 main paediatric rheumatology units identified that just five units had a team member with PPI included in their job description [14]. Furthermore, in order to limit recruitment bias, we adopted a maximum variety purposive sampling approach to sampling for this study. This aimed to encompass the range of AYA development by having focus groups for the first 2 stages (early and mid) and the latter 2 stages (late adolescence and young adulthood). We also involved centres in all 4 devolved nations of the UK in order to capture the range of services for this age group, in both urban and rural settings. There has been a significant growth in specialist services for this age group in recent years in the UK although significant delays in referral persist for certain conditions eg juvenile idiopathic arthritis [18]. To further maximise the diversity within our recruitment we recruited via charities in an attempt to recruit young people not being treated at centres with specific paediatric, adolescent and/or young adult rheumatology services. These young people potentially had less access to research opportunities.

However despite efforts to recruit a maximum variety sample, due to the relative small sample sizes required within qualitative research there will still be some limitations in terms of the diversity of the sample. For example, research-naïve young people or those with very mild disease and/or who are happy with their current care may not have perceived a study focused on beliefs about research involvement as being relevant to them. However we did successfully recruit such young people in this study. Another group less likely to engage in research are those young people who have become disengaged from their rheumatology care. Understanding their perspectives would be particularly valuable. Reasons for non-response are important in any research but particularly pertinent to adolescent health as some studies have shown that those who fail to respond have poorer outcomes compared to adult non-responders [19].

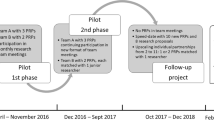

An important impact of this study is that, incorporating the clear advice regarding involvement in the current study, we have since established a national young person’s advisory group to inform BANNAR research.

The group is called Your Rheum (https://yourrheum.org/) [20] and is currently holding face to face meetings several times a year and involving young people online in research.

Finally, whilst acknowledging the exploratory nature of the current study, one could argue that many of these findings are also true for adult populations. However, implementing change in the adolescent and young adult group in relation to involvement, just as in clinical care, requires developmentally appropriate approaches which change over time as young people grow and develop [11].

Young people identified a lack of opportunity or a perception of poor access to research and research involvement as a primary barrier to research involvement. This suggests that efforts are needed to increase researchers’ awareness and understanding of PPI and its’ likely impact. Increased awareness may increase researchers’ confidence in involving young people in their work and lead to a wider range of research involvement opportunities becoming available. As part of this current project, models of good research involvement practice in this area beyond rheumatology were collated to serve as a future resource for researchers [21]. Since the Clinical Studies Group in Paediatric Rheumatology was established [22], research involvement outside of large teaching hospitals has significantly improved but further work is still required, if we consider the views of participants in the current study of their poor access to involvement opportunities. Investment into appropriate staffing for such initiatives is supported by the finding that recruitment to this particular study was better in those centres with a team member with PPI as part of their job description.

The findings from this exploratory study also suggest that further work is needed to increase young people’s awareness of rheumatology research within the UK. The national paediatric rheumatology clinical studies group, which supports a portfolio of clinical studies across the UK states:

“All children and young people in the UK with a rheumatological condition may be given the opportunity to be enrolled in a clinical trial or well conducted clinical study from point of diagnosis onwards” [22].

The current study has revealed that it will be important to ensure both that the aims and purposes of young people’s involvement in research are made clear to them as well as receiving feedback on both their involvement as well as their research participation. It will also be important to explore the language used to explain research participation and involvement to young people to gain some insights into why the nature of involvement is sometimes misconstrued.

In this current study, few young people had experience of being involved in influencing research, with those treated in large teaching hospitals being more likely to report having experience. Despite this finding, all young people strongly believed that they should be involved in research, particularly as they had lived experience of their condition and could provide a perspective which would otherwise not be available. Acknowledgement of the lived experience of young people with rheumatic disease is therefore as imperative for researchers as has also been reported for clinicians [23].

Understanding and evaluating the impact of patient and public involvement in general, and for young people is becoming an increasingly important issue. Evaluation frameworks for involvement have been developed for adults but it is still unclear whether they can be used effectively with young people [24]. The involvement of young people in research has been reported to have a positive impact on recruitment and retention [25]. However, Holland et al. cautions practitioners “against assuming that participatory research per se necessarily produces “better” research data, equalises power relations or enhances ethical integrity” [26]. Therefore, research is needed to explore how young people perceive their roles as active research partners in the context of chronic health conditions when involvement could potentially be an additional burden [27].

Conclusions

This exploratory study highlights the importance of further enhancing the culture of research in the adolescent and young adult age group, to increase young people’s awareness of opportunities for both research participation and research involvement. In the UK, BANNAR and the YOURR project have made initial steps in doing so in rheumatology.

What is known about this subject?

Involving people of all ages in health research is now widely advocated. To date, no studies have explored whether and how young people with rheumatic conditions want to be involved in influencing health research.

What this study adds?

-

This study highlights the need to increase the culture of research in some clinical specialities (including Rheumatology) to improve young people’s access to research participation and involvement opportunities

-

Providing support and training to researchers to increase their confidence in involving young people in their work is also likely to increase the number of research involvement opportunities available.

-

Being flexible in the range of approaches used to involve young people in research may increase the likelihood that a more diverse group of young people will become involved.

Abbreviations

- BANNAR:

-

Barbara Ansell National Network for Adolescent Rheumatology.

- BSPAR:

-

British Society for Paediatric and Adolescent Rheumatology

- CHAQ:

-

Childhood Health Assessment Questionnaire

- NHS:

-

National Health Service

- PPI:

-

Patient and Public Involvement

- YOURR:

-

Young People’s Opinions Underpinning Rheumatology Research

References

Bate J, Ranasinghe N, Ling R, Preston J, Nightingale R, Denegri S. Public and patient involvement in paediatric research. Arch Dis Child Educ Pract Ed. 2016;101(3):158–61.

Elliott J. Health Research Authority strategy for Patient Involvement 2013;NHS Health Research Authority. (https://www.hra.nhs.uk/planning-and-improving-research/best-practice/involving-public/ (Accessed 12 Jan 2018) Accessed 27 May 2017).

Generation R website. http://generationr.org.uk/ (Accessed 12 Jan 2018).

Hunter L, Sparrow E, Modi N, Greenough A. Advancing child health research in the UK: the Royal College of Paediatrics and Child Health Infants' Children's and young People's research charter. Arch Dis Child. 2017 Apr;102(4):299–300.

NIHR INVOLVE Jargon buster. http://www.invo.org.uk/resource-centre/jargon-buster/page/2/?letter=I (Accessed 12 Jan 2018).

Dudley L, Gamble C, Preston J, Buck D, EPIC Patient Advisory Group., Hanley B, Williamson P, Young B. What difference does patient and public involvement make and what are its pathways to impact? Qualitative study of patients and researchers from a cohort of randomised clinical trials. PLoS One. 2015;10(6):e0128817.

Boote J, Wong R, Booth A. ‘Talking the talk or walking the walk?’ A bibliometric review of the literature on public involvement in health research published between 1995 and 2009. Health Expect. 2015;18(1):44–57.

McDonagh JE, Dovey-Pearce G. Research methods in adolescents in. In: Thomet C, Moons P, Schwerzmann M, editors. “Adolescents with congenital heart disease”. Switzerland: Springer International Publishing Switzerland; 2016. p. 207–21.

Viner RM, Ozer EM, Denny S, Marmot M, Resnick M, Fatsui A, Currie C. Adolescence and the social determinants of health. Lancet. 2012;379(9826):1641–52.

Dudley L, Gamble C, Allam A, Bell P, Buck D, Goodare H, Hanley B, Preston J, Walker A, Williamson P, Young B. A little more conversation please? Qualitative study of researchers’ and patients’ interview accounts of training for patient and public involvement in clinical trials. Trials. 2015;16(1):190.

Sammons HM, Wright K, Young B, Farsides B. Research with children and young people: not on them. Arch Dis Child. 2016 Dec;101(12):1086–9.

Barbara Ansell National Network for Adolescent Rheumatology website (BANNAR). http://bannar.org.uk/ (Accessed 12 Jan 2018).

Parsons S, Thomson W, Cresswell K, Starling B, JE MD. Barbara Ansell National Network for adolescent rheumatology. What do young people with rheumatic disease believe to be important to research about their condition? A UK-wide study. 2017;15(1):53.

Parsons S, Dack K, Starling B, Thomson W, McDonagh JE. Study protocol: determining what young people with rheumatic disease consider important to research (the young People’s opinions underpinning rheumatology research-YOURR project). Research Involvement and Engagement. 2016;2(1):1.

Arthritis Care website. 2018. https://www.arthritiscare.org.uk/ (Accessed 28 Apr 2018).

Ritchie J, Lewis J. Qualitative research practice- a guide for social science students and researchers. London: Sage; 2003.

Nugent J, Ruperto N, Grainger J, Machado C, Sawhney S, Baildam E, Davidson J, Foster H, Hall A, Hollingworth P, Sills J, Venning H, Walsh JE, Landgraf JM, Roland M, Woo P, Murray KJ. Paediatric rheumatology international trials organisation. The British version of the childhood health assessment questionnaire (CHAQ) and the child health questionnaire (CHQ). Clin Exp Rheum. 2001;19(23):S163–7.

McErlane F, Foster HE, Carrasco R, Baildam EM, Chieng SE, Davidson JE, Ioannou Y, Wedderburn LR, Thomson W, Hyrich KL. Trends in paediatric rheumatology referral times and disease activity indices over a ten-year period among children and young people with juvenile idiopathic arthritis: results from the childhood arthritis prospective study. Rheumatology (Oxford). 2016;55(7):1225–34.

Mattila VM, Parkkari J, Rimpela A. Adolescent survey non-response and later risk of death. A prospective cohort study of 78609 persons with 11 year follow-up. BMC Public Health. 2007;7:87.

Your Rheum website - https://yourrheum.org/ (Accessed 28 Apr 2018).

Dack K, Williams H, Parsons S, Thomson W, McDonagh JE On behalf of the Barbara Ansell National Network for adolescent rheumatology. Summary of good practice when involving young people in health-related research. 2016 (available on www.bannar.org.uk, Accessed 12 Jan 2018).

Thornton J, Beresford MW, Clayton P. Improving the evidence base for treatment of juvenile idiopathic arthritis: the challenge and opportunity facing the MCRN/ARC Paediatric rheumatology clinical studies group. Rheumatology. 2008;47:563–6.

Hart RI, McDonagh JE, Thompson B, Foster HE, Kay L, Myers A, Rapley T. Being as normal as possible: how young people ages 16-25 years evaluate the risks and benefits of treatment for inflammatory arthritis. Arthritis Care Res (Hoboken). 2016 Sep;68(9):1288–94.

Public Involvement Impact Assessment Framework (Piiaff) http://piiaf.org.uk/ (Accessed 12 Jan 2018).

Shrewsbury VA, O'Connor J, Steinbeck KS, Stevenson K, Lee A, Hill AJ, Kohn MR, Shah S, Torvaldsen S, Baur LA. A randomised controlled trial of a community-based healthy lifestyle program for overweight and obese adolescents: the Loozit® study protocol. BMC Public Health. 2009 Apr 29;9(1):119.

Holland S, Renold E, Ross NJ, Hillman A. Power, agency and participatory agendas: a critical exploration of young people’s engagement in participative qualitative research. Childhood. 2010;17:360–75.

Van Staa A, Jedeloo S, Latour JM, Trappenburg MJ. Exciting but exhausting: experiences with participatory research with chronically ill adolescents. Health Expect. 2010;13(1):95–107.

Acknowledgements

This article presents independent research funded by Arthritis Research UK BANNAR. The views expressed in this article are those of the authors and not necessarily those of the NHS, the National Institute for Health Research or Arthritis Research UK. We would like to thank all of the young people who took part in this study and the clinicians including members of the Barbara Ansell National Network for Adolescent Rheumatology, PPI coordinators and other individuals who facilitated their involvement. Arthritis Care for their support in the recruitment phase of the project.

Funding

We thank the Arthritis Research UK for their support: Arthritis Research UK grant number 20164; Centre for Epidemiology 20380 and Centre for Genetics and Genomics 20385.

Availability of data and materials

The datasets generated and/or analysed during the current study are not publicly available due to the restrictions of the ethics approval originally obtained.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Consortia

Contributions

JMcD wrote the successful application for funding. SP and JMcD co led on the writing of this manuscript and all authors read and approved the final version. JMcD and WT are the co-principal investigators with overall responsibility for the project. SP and JMcD moderated the focus groups. SP is the research associate who led the data analysis. JMcD, SP, WT, BS and KC were involved in data interpretation. KC is also the facilitator for the young people’s involvement group Your Rheum. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

The study received ethics approval from Newcastle and North Tyneside NRES Committee. Ethics no 14/NE/1112.

Over 16 s gave their individual consent to participate and 11–15 year olds gave their assent following parental consent. Parents of those aged 11–15 were able to accompany participants but waited in a separate room whilst their child took part.

Competing interests

“The authors declare that they have no competing interests”.

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made. The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver (http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/) applies to the data made available in this article, unless otherwise stated.

About this article

Cite this article

Parsons, S., Thomson, W., Cresswell, K. et al. What do young people with rheumatic conditions in the UK think about research involvement? A qualitative study. Pediatr Rheumatol 16, 35 (2018). https://doi.org/10.1186/s12969-018-0251-z

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s12969-018-0251-z