Abstract

Background

Cardiovascular disease is a significant cause of morbidity and mortality in patients with end-stage renal disease (ESRD) and kidney transplant (KT) patients. Compared with left ventricular (LV) ejection fraction (LVEF), LV strain has emerged as an important marker of LV function as it is less load dependent. We sought to evaluate changes in LV strain using cardiovascular magnetic resonance imaging (CMR) in ESRD patients who received KT, to determine whether KT may improve LV function.

Methods

We conducted a prospective multi-centre longitudinal study of 79 ESRD patients (40 on dialysis, 39 underwent KT). CMR was performed at baseline and at 12 months after KT.

Results

Among 79 participants (mean age 55 years; 30% women), KT patients had significant improvement in global circumferential strain (GCS) (p = 0.007) and global radial strain (GRS) (p = 0.003), but a decline in global longitudinal strain (GLS) over 12 months (p = 0.026), while no significant change in any LV strain was observed in the ongoing dialysis group. For KT patients, the improvement in LV strain paralleled improvement in LVEF (57.4 ± 6.4% at baseline, 60.6% ± 6.9% at 12 months; p = 0.001). For entire cohort, over 12 months, change in LVEF was significantly correlated with change in GCS (Spearman’s r = − 0.42, p < 0.001), GRS (Spearman’s r = 0.64, p < 0.001), and GLS (Spearman’s r = − 0.34, p = 0.002). Improvements in GCS and GRS over 12 months were significantly correlated with reductions in LV end-diastolic volume index and LV end-systolic volume index (all p < 0.05), but not with change in blood pressure (all p > 0.10).

Conclusions

Compared with continuation of dialysis, KT was associated with significant improvements in LV strain metrics of GCS and GRS after 12 months, which did not correlate with blood pressure change. This supports the notion that KT has favorable effects on LV function beyond volume and blood pessure control. Larger studies with longer follow-up are needed to confirm these findings.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Chronic kidney disease (CKD) is well-known risk factor for adverse cardiovascular events [1]. Despite advances in dialysis and kidney transplant (KT), patients with end-stage renal disease (ESRD) and KT continue to experience high cardiovascular morbidity and mortality, even following KT [2,3,4].

While left ventricular (LV) hypertrophy (LVH) has been identified as a marker of poor prognosis and adverse outcomes in dialysis patients, a large proportion of ESRD patients have preserved LV ejection fraction (LVEF) [5,6,7]. However, measurable reduction in LVEF represents late LV dysfunction, and may only identify CKD patients with well-established cardiovascular disease [8]. Although structural changes such as LV mass (LVM) and volume have been associated with subsequent reduction in LVEF, LV myocardial deformation (strain) is likely a more sensitive measure of early subclinical myocardial dysfunction as it directly reflects the motion of myocardial fibers. Indeed, strain has emerged as a marker of LV function, and its role has been studied in a variety of heart diseases, providing incremental prognostic information beyond LVEF [9,10,11,12]. The most well-established strain parameter is global longitudinal strain (GLS), which is more sensitive than LVEF for detection of subclinical LV dysfunction [9, 12]. Given that LV strain is less load dependent, its use to evaluate changes in LV function is particularly attractive in ESRD patients who are subject to large fluctuations in preload and afterload [13]. Indeed, previous studies have shown that LV strain is likely a better measure of systolic function than LVEF in ESRD [14, 15].

Prior studies have demonstrated improved LVEF and regression of LVM post-KT [16, 17], but insufficient data exist for evaluating the impact of KT (the most effective form of renal replacement therapy) on LV myocardial function beyond changes in loading conditions. Accordingly, our study aimed to address whether KT improves systolic function as measured by LV strain, beyond volume and blood pressure control. To this end, we conducted an observational cohort study to compare cardiovascular magnetic resonance imaging (CMR)-derived changes in LV strain over 12 months between ESRD patients who underwent KT and those who remained on dialysis. There are also a paucity of data delineating the relationships between changes in myocardial strain (function), and LV remodeling (structure), in the setting of KT. As CMR is the gold standard for examining both cardiac structure (LVM and LV volumes) and function, it is of particular interest to evaluate whether a structure-function relationship exists in this patient population. Accordingly, we also examined the relationships between LV strain and other cardiac parameters including LVEF, LVM, and LV volumes.

Methods

Study design

The full details of the study design have been described previously [18]. Briefly, we conducted an observational cohort study of adult patients on hemodialysis or peritoneal dialysis who were single-organ KT candidates at three academic dialysis and KT centers in Ontario, Canada: St. Michael’s Hospital and Toronto General Hospital, both in Toronto, Ontario and London Health Sciences Centre in London, Ontario between August 30, 2010 and February 14, 2014.

The study was approved by the Research Ethics Boards at all study sites and all study participants provided informed consent. The inclusion criteria were: age ≥ 18 years old, approved or likely to be approved for a KT (living donor or deceased donor wait list), renal replacement with hemodialysis or peritoneal dialysis, living donor recipients at low immunological risk for graft rejection, and ability to provide informed consent.

Exclusion criteria included multi-organ transplant, pre-dialysis, daily hemodialysis, high immunological risk as per the site investigator, unlikely to receive transplant, acute coronary syndrome or coronary revascularization procedure within 6 months of enrollment, heart failure, permanent atrial fibrillation, pregnancy or intention to pursue pregnancy within 12 months, and a life expectancy < 1 year.

Patients who met the study entry criteria were separated into two groups based on availability of a potential living kidney donor. The KT group included dialysis patients who were expected to receive a living donor KT in the subsequent two months. The dialysis group comprised patients who were eligible for KT but had no living donors and were expected to remain on dialysis for the following 24 months.

Blood pressure was measured using a validated automated device according to American Heart Association Guidelines.

CMR image processing

Baseline CMR was performed following recruitment (i.e. after enrollment and prior to KT), followed by repeat CMR at 12 months post-transplant or post-recruitment for the dialysis group. If a patient in the dialysis group unexpectedly received a KT within 12 months, the second CMR was performed 12 months after the original CMR. For hemodialysis patients, CMR was performed following dialysis to minimize effects of intravascular volume shifts. All CMR examinations were performed with a 1.5 T scanner (Intera, Philips Healthcare, Best, The Netherlands, or a GE Signa Excite Cv, Milwaukee, Wisconsin, USA) using a cardiac coil and retrospective electrocardiographic gating. The Philips 1.5 T scanner used a 5-channel (SENSE) cardiac coil. One GE 1.5 T scanner used a 32-channel cardiac coil, while another GE 1.5 T scanner used an 8-channel cardiac coil. Standard protocols using validated, commercially available sequences were used. Images were obtained with breath-hold at end-expiration. Typical balanced steady-state free precession sequence (bSSFP) parameters were used to acquire cine images in long axis planes followed by sequential short-axis cine loops with the following parameters: repetition time 4 ms, time to echo 2 ms, slice thickness 8 mm, field of view 320–330 × 320-330 mm (tailored to achieve optimal spatial resolution and image acquisition time), matrix size 256 × 196, temporal resolution of < 40 ms (depending on the heart rate) and flip angle 50 degrees. Prior to imaging processing, all CMR studies were de-identified and assigned a unique identification code. CMR studies were analyzed with commercially available cvi42 software (Circle Cardiovascular, Calgary, Canada). An experienced reader measured LVEF and LVM, while another experienced reader independently performed LV strain analysis. Readers were blinded to patient group (KT versus dialysis patients) and timing of the CMR (baseline versus 12 months).

LV end-diastolic volumes (EDV) and end-systolic volume (ESV) were measured using the short-axis cine images by manually tracing endocardial contours during end-diastole and end-systole, using the blood volume method, including papillary muscles and trabeculations. LVEF was calculated as (LVEDV-LVESV)/LVEDV × 100%. LVM was calculated using the area occupied between the endocardial and epicardial borders multiplied by the slice thickness and interslice distance, using contiguous short-axis slices at end-diastole [19]. LVEDVi, LVESVi, and LVMi were normalized (indexed) by dividing their values by the subject’s body surface area.

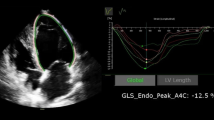

LV strain imaging was performed using feature-tracking (FT) CMR according to previously published methods [20]. Endocardial and epicardial borders were manually drawn in the end-diastolic frame, which were then automatically propagated (tracked) throughout the cardiac cycle. The peak systolic strain was derived from the distance moved between frames. Systolic strain is the percent change in length relative to baseline length (Langrangian strain); a positive strain implies elongation while negative strain implies shortening (e.g., a negative change in GLS from baseline to 1-year means improved function) [21]. The peak systolic LV strain parameters calculated were GLS, global circumferential strain (GCS), and global radial strain (GRS). Multiple 2D long-axis cine images (2, 3, and 4-chamber views) were tracked to derive GLS, while short-axis cine images were used to derive GCS and GRS. Strain was obtained for each segment and the global values were defined as the mean of all segmental values.

Biomarkers

N-Terminal - brain natriuretic peptide (NT-BNP) was measured using the Cobas 6000 601e assay (Roche, Mississauga, Ontario, Canada). We also measured the growth differentiation factor-15 (GDF-15), a novel biomarker expressed in response to tissue injury with elevations implicated in worsening kidney function among patients with CKD [22], using Quantikine ELISA assay (R&D Systems Inc., Minneapolis, Minnesota, USA).

Statistical analysis

Continuous data are expressed as mean with standard deviation or median with interquartile range (IQR), as appropriate. The Student’s t-test was used for normally distributed continuous data while the Kruskal–Wallis test was used for non-normally distributed continuous data. Chi-square or Fisher’s exact test was used to compare categorical variables between groups. For within-group comparisons between the baseline and 12-month follow-up CMR parameters, a paired t-test was used. The relationships between change in LV peak systolic strain parameters with changes in LVEF, LVMi, LVEDVi, LVESVi, blood pressure, dialysis vintage, and renal function as measured by estimated glomerular filtration rate (eGFR) and creatinine level at 12 months were examined using non-parametric Spearman’s correlation test. The relationships between baseline NT-BNP, GDF-15, and c-reactive protein (CRP) with LV strain parameters were examined using non-parametric Spearman’s correlation test. To determine intra-observer reproducibility, a random sample of 20 CMRs were measured by the same reader in 6 months, and intra-class correlation coefficients for absolute agreement were calculated. Statistical significance was defined as a two-sided p value < 0.05. All data were analyzed using SPSS version 22 (International Business Machines Corp., Armonk, New York, USA).

Results

We consented 89 patients of whom 79 (22 peritoneal dialysis and 57 hemodialysis; 40 patients continued on dialysis and 39 patients received KT) had complete CMR-derived measurements at baseline and at 12 months (Table 1). Incomplete CMR were due to post-transplant graft failure and patient reluctance to undergo a second CMR. Two patients crossed over from the dialysis control group to the KT group due to receipt of KT from a deceased donor sooner than anticipated, and included in the KT group for analysis. One patient in the KT group underwent arteriovenous fistula closure during 12-month follow up. Prior to baseline CMR, the median (interquartile range [IQR]) dialysis vintages of patients in the dialysis and KT group were 24 (15–42) and 14 (9–28) months, respectively. We found no significant correlation between dialysis vintage and baseline CMR parameters (all p > 0.05, data not shown).

Compared to dialysis patients, KT patients were significantly younger (47 versus 56 years), with similar sex distribution and body mass index. There were no significant differences in cardiovascular risk factors, prior cardiovascular events, distribution of etiology for ESRD, or cardiovascular medications (with the exception of less statin use in KT group). At baseline, LVEDVi, LVESVi, and cardiac index were significantly higher in KT patients compared to dialysis patients, while no difference in LV strain parameters, LVEF, or LVMi was observed (Table 1).

Over the 12-month period, two myocardial infarctions and one cerebrovascular accident were observed in the dialysis group, while no cardiac event was observed in the KT group.

Table 2 shows the measured CMR parameters at baseline and at 12 months for dialysis and KT patients. When compared to baseline, mean LVEF for KT patients significantly improved at 12-month follow-up (57.6% ± 6.4% versus 60.7% ± 6.8%, p = 0.001), while no significant change was observed in dialysis patients (59.8% ± 6.6% versus 60.7% ± 5.6%, p = 0.40). Despite significant LVEF improvement compared to baseline for KT patients, comparison of change (from baseline to 12 months) between KT and dialysis patients did not reach statistical significance (mean difference − 2.5, 95% confidence interval [CI] -5.2-0.2, p = 0.070). The cardiac index at 12 months for dialysis and KT group were 3.6 ± 1.1 and 3.7 ± 0.8 L/min/m2, respectively, with no significant difference in the change from baseline between the two groups (mean difference 0.3, 95% CI -0.07-0.7, p = 0.10).

Compared to baseline, KT group patients had significantly improved LV peak systolic strain parameters GCS (p = 0.007; Fig. 1) and GRS (p = 0.003; Fig. 2) at 12 months, while GLS was significantly worse (p = 0.026; Fig. 3). No significant improvement in LV strain parameters was observed for dialysis group patients. When comparing the 12-month changes between KT and dialysis patients, improvements in GCS (1.3, 95% CI -0.02-2.6, p = 0.048; Fig. 1) and GRS (− 5.2, 95% CI -0.5-9.9, p = 0.031; Fig. 2) were significant, while the decline in GLS was not (− 0.4, 95% CI -1.7-0.9, p = 0.52; Fig. 3). The intra-class correlation coefficients for intra-observer reproducibility were 0.91 (95% CI 0.77-0.96, p<0.001), 0.90 (95% CI 0.77-0.96, p<0.001), and 0.86 (95% CI 0.68-0.94, p<0.001), for GLS, GRS, and GCS, respectively.

Changes in left ventricular strain parameter global circumferential strain assessed by cardiovascular magnetic resonance imaging at baseline and at 12-month in dialysis and transplant patients. *p denotes comparison of change (from baseline to 12 months) between kidney transplant (KT) and dialysis patients. Vertical bars denote 95% confidence intervals

Changes in left ventricular strain parameter global radial strain assessed by cardiovascular magnetic resonance imaging at baseline and at 12-month in dialysis and transplant patients. *p denotes comparison of change (from baseline to 12 months) between KT and dialysis patients. Vertical bars denote 95% confidence intervals

Correlations between temporal changes in cardiac parameters and blood pressure are summarized in Table 3. For the entire cohort, there were significant correlations between change in LVEF and all three LV strain parameters from baseline to 12 months. We observed significant correlations between improvements in GCS and GRS with reductions in LVEDVi, and LVESVi, but not for GLS. At baseline, GLS was correlated with LVMi (Additional file 1). There was a significant weak positive correlation between changes in LVMi and GLS. These findings were similar for KT patients. We found no significant correlation between changes in LV strain parameters from baseline to 12 months and dialysis vintage (all p > 0.4, data not shown).

At 12 months, the mean blood pressure for dialysis and KT patients were 135 ± 29/77 ± 13 and 126 ± 17/79 ± 11 mmHg, respectively. No correlation was observed between change in LV strain parameters and change in blood pressure (Table 3). The number of antihypertensive medications used was significantly less in the KT group at 12 months compared to baseline (2.4 ± 1.7 versus 1.5 ± 1.0, p = 0.001), while no difference was found for dialysis patients (2.1 ± 1.6 versus 2.1 ± 1.6, p = 0.54).

At 12 months, the median creatinine was 716 (IQR 580–894) and 108 (IQR 94–128) for the dialysis and KT groups, respectively. Following KT, there was no significant correlation between eGFR or creatinine with changes in LVEF, LVEDVi, LVESVi, LVMi, or systolic strain parameters (all p > 0.1) at 12 months.

We evaluated the association between biomarkers and LV strain at baseline in the overall cohort. At baseline, NT-BNP concentration was significantly correlated with LV strain parameters GLS (Spearman’s correlation coefficient 0.27, p = 0.019), GCS (Spearman’s correlation coefficient 0.38, p = 0.001), and GRS (Spearman’s correlation coefficient − 0.32, p = 0.005), suggesting that higher NT-BNP was associated with worse LV subclinical myocardial function. GDF-15 concentration was significantly correlated with LV strain parameter GLS (Spearman’s correlation coefficient 0.33, p = 0.003), but not GCS (Spearman’s correlation coefficient 0.088, p = 0.45) or GRS (Spearman’s correlation coefficient − 0.068, p = 0.56). CRP concentration was not correlated with LV strain parameters (all p > 0.1).

Discussion

We conducted a prospective multi-centered cohort study in maintenance dialysis patients who were KT candidates to evaluate LV function changes after KT using FT-CMR strain imaging. At 12-month post-KT, we observed significant improvements in key parameters of LV strain (GCS and GRS), with a concurrent improvement in LVEF. This was in contrast to the lack of change observed in these parameters for patients who remained on dialysis. To our knowledge, this is the first study to evaluate myocardial strain by CMR in ESRD patients before and after KT. These findings support the notion that KT has favorable effects on LV function, and highlight the utility of CMR strain to detect subclinical improvements in myocardial function following KT.

In this study, both dialysis and KT patients had generally preserved LVEF at baseline. This is not surprising given the fact that LVEF represents late LV dysfunction [8, 23], and is consistent with previous studies demonstrating preserved LVEF using echocardiography in a large proportion of ESRD patients [5,6,7]. Although LVEF significantly improved from baseline to 12 months in the KT group, the change only trended towards significance when compared to dialysis patients. This may be attributed to the fact that most patients had preserved LVEF before KT, and possibly a selection bias since patients considered to be KT-eligible represent the healthiest subset of the dialysis population. These findings are consistent with studies by Wali et al. and Casas-Aparicio et al. demonstrating improved LVEF following KT [24, 25].

Although echocardiography is more accessible for strain imaging, its accuracy is limited by the adequacy of acoustic windows, image quality, and operator-dependent variability. Furthermore, dialysis-associated fluctuations in intravascular volume and intracardiac volume likely further compromise the reliability and accuracy of ventricular function indices by echocardiography [26]. As such, CMR is the gold standard to provide accurate and reproducible measurements of volume and mass due to lack of geometric assumptions, and less load-dependence. CMR with myocardial tagging is currently the reference standard technique for myocardial deformation. Strain can be measured by harmonic phase analysis (HARP) and spatial modulation of magnetisation (SPAMM) [27, 28], allowing detection of LV dysfunction even in asymptomatic subjects without cardiovascular disease [29]. The novel FT-CMR technique for measuring strain using bSSFP sequence, unlike myocardial tagging, requires no additional sequences as the cine images required are part of the routine LV study protocol, allowing for rapid acquisition and post-processing. Moreover, FT-CMR has been validated against myocardial tagging using HARP and SPAMM for systolic and diastolic strain [30, 31]. In addition, it is important to highlight that the advantage of strain over LVEF is that it is less sensitive to load changes. Accordingly, in this study, we measured LV peak systolic strain GLS, GCS, and GRS by FT-CMR to assess the impact of KT on systolic function.

While we demonstrated a significant improvement in GCS and GRS after KT when compared to dialysis patients, no improvement in GLS was observed. These changes in GRS and GCS were correlated with changes in LVEF. Of the strain parameters measured by speckle tracking echocardiography, consensus recommendation favoured use of GLS for early detection of subclinical LV dysfunction [32]. This is because GLS has been reported to precede clinical evidence of overt systolic dysfunction in a variety of cardiomyopathies [33, 34]. Similarly, in the ESRD population, a recent study by Hensen et al. demonstrated a high prevalence of impaired GLS (measured by echocardiography) in pre-dialysis and dialysis patients with preserved LVEF, and that impaired GLS was an independent risk factor for HF and mortality. Our strain results are in contrast with Hewing et al., which showed improvement in GLS post-KT as assessed by echocardiography in a population of patients with preserved LVEF at baseline [35]. The precise reason for the discrepant findings is unclear, and may be partly attributed to different imaging modality used. Moreover, the reason for improvement in GCS and GRS but not GLS is elusive. It is plausible that the improvement in LVEF may be due to improvement in GCS and GRS compensating for abnormal GLS. Prior studies examining LV strain parameters demonstrated that GLS deteriorates in early stages of myocardial pathologic conditions, before reduction in LVEF, while GCS remain preserved or increased to compensate for GLS function [36,37,38]. There are no prior studies specifically investigating the temporal sequence of deterioration or improvement of cardiac strain following a cardiovascular intervention. In patients who received cardiac resynchronization therapy and aortic valve replacement, some studies demonstrated that improvement in GCS rather than GLS is crucial for favorable remodeling, while others demonstrated improvement in both GCS and GLS [38,39,40,41,42,43]. Hence, it is also plausible that GCS and GRS are more sensitive to the effects of treatment (KT) and evolve before GLS. We also note that GCS is the most reproducible strain parameter by FT-CMR [21]. To the best of our knowledge, no prior studies investigated the temporal sequence of deterioration or improvement of cardiac strain in this setting. As highlighted above, studies have implicated abnormal GLS as a predictor of worse prognosis in CKD and dialysis patients [6, 14, 44], which may be secondary to myocyte hypertrophy and microvascular ischemia due to myocardial fibrosis [45]. Hence, the long-term implications for lack of improvement in GLS following KT are unclear and need to be addressed in future studies with longer follow-up CMR.

We examined the relationships between LV strain parameters and LV volumes and blood pressure to determine whether a relationship exists between structural and functional changes. We found improvements in GCS and GRS, despite a concurrent reduction in LV volumes LVEDVi (surrogate of preload) and LVESVi. The correlation between improvement in LV strain with decreased LV volume suggest that improved LV systolic function is likely attributed to KT rather than loading changes. Similarly, evaluation of blood pressure changes is required for interpretation of LV function change. Afterload is the tension or stress generated in the LV wall during myocardial contraction to eject blood. An assumption can be made such that afterload is proportional to the aortic pressure that the LV must overcome to eject blood, with systolic blood pressure being a surrogate of afterload. In this study, we did not observe a significant change in blood pressure following KT compared to baseline, and there was no correlation with LV strain. Interestingly, KT patients required significantly fewer antihypertensive medications at 12 months, while number of medications remained similar in dialysis patients. Taken together, our findings show that reduction in LVEDVi and LVESVi at 12 months occurred without blood pressure change, suggesting that strain improvements were not simply a result of changes in load.

Patients with advanced CKD frequently have increased LVM, which is further exacerbated by the receipt of dialysis [46, 47]. In trials of dialysis intensification, LVM served as a well-established surrogate endpoint for adverse cardiovascular events [48]. Although LVM regression has been previously evaluated [49], there is currently a knowledge gap as to whether LV functional change is associated with structural change. Evaluating change in LV function using strain parameter post-transplant is imperative in light of recent studies supporting the role of myocardial strain as an independent predictor of CKD mortality [14, 15]. Taken together, our study is one of the first to address this key question, with findings suggestive of systolic function improvement 12 months after KT.

We found no correlation between changes in LVEF or LV strain parameters with changes in renal function as reflected by eGFR and creatinine at 12 months post-transplant. These data do not provide insight into whether mitigation of uremia is a potential mediator for LV functional changes observed following transplant. Furthermore, although creatinine is a measure of renal function, creatinine alone likely does not adequately reflect all the beneficial cardio-renal effects. The reduction in mortality is likely related to myriad of metabolic improvements that result in favourable effects on cardiac function, including improvement in anemia, calcium-phosphate profile, reduction of parathyroid hormone, and neurohormones [50].

Our study has a number of strengths. There are limited data on CMR-derived strain in CKD and KT patients. To the best of our knowledge, the present study is the first to examine whether systolic strain by FT-CMR is a useful tool for identifying improvement in LV systolic function following KT. Advantages of CMR include greater reproducibility compared to echocardiogram, particularly pertaining to LVM and LV volume whereby patients on dialysis (i.e. control group in our study) experience greater fluctuations in volume. CMR was performed using different vendors at 3 centres, enhancing the generalizability of our results. CMR analyses were completed in a blinded fashion and serial CMRs were analyzed in random order. Our study reported temporal changes in systolic strain at 12 months after KT, providing one of the longest longitudinal follow-up in the literature. In addition, our results support the notion that KT improves LV contractility over time. Although the precise pathophysiological reasons for improved cardiovascular outcomes following KT compared to dialysis remain to be clarified, it is plausible that survival benefit is at least in part due to amelioration of metabolic derangements and efficient clearance of numerous uremic toxins that may be cardiotoxic [51] and have negative inotropic effects [52,53,54].

This study has a number of evident limitations. Since this was not a randomized trial, the relationship between KT and various strain parameters cannot be viewed as causal, thus causality cannot be established from our results. However, randomized trials of KT are logistically very challenging to conduct. Secondly, we could not evaluate changes in strain long term beyond our study period (> 12 months) and longer follow-up is needed to assess whether strain improvements are sustained following KT. Our study may lack power in identifying important inter-group differences due to the relatively small number of patients. We were not able to provide a precise reason for deterioration of strain parameter GLS which was discordant with the improvements in GCS and GRS. Our study was not designed or powered sufficiently to address the prognostic role of GLS versus GCS or GRS in KT patients. Future studies are required to address the temporal nature of improvement of the 3 strain parameters in KT patients. While immunosuppressive agents used in KT patients (steroids and calcineurin inhibitors) may exacerbate cardiovascular disease for a variety of reasons, our study was not designed or adequately powered to definitively determine the effect of immunosuppressive regimens on myocardial function, which would be better addressed in a separate randomized study. Our study sample size may have been underpowered to detect associations between CMR parameters and blood pressure. We did not measure myocardial strain by echocardiogram and could not determine the correlations between strain measurements measured by different imaging modalities. Given our small sample size, together with limited follow-up of 1-year timeframe and low number of cardiovascular events observed, our study is ill-equipped to determine the incremental prognostic value of strain, although our measured CMR parameters are known to be important surrogates for clinical events in diverse cardiovascular conditions. Finally, other CMR parameters, such as diastolic function, are beyond the scope of this study.

Conclusion

In this prospective longitudinal study comparing KT patients with those who remained on dialysis, we observed a significant improvement in LV systolic strain GCS and GRS at 12 months, but not GLS, with corresponding improvement in LVEF and LV volumes. Our results support the notion that KT likely has favourable effects on LV structure and function. Additional studies are required to confirm these findings in a larger cohort of KT patients with longer follow up.

Abbreviations

- BMI:

-

Body mass index

- bSSFP:

-

Balanced steady state free precession

- CI:

-

Confidence interval

- CKD:

-

Chronic kidney disease

- CMR:

-

Cardiovascular magnetic resonance

- CRP:

-

C-reactive protein

- EDV:

-

End diastolic volume

- EDVi:

-

End diastolic volume index

- eGFR:

-

Estimated glomerular filtration rate

- ESRD:

-

End-stage renal disease

- ESV:

-

End systolic volume

- ESVi:

-

End systolic volume index

- FT:

-

Feature tracking

- GCS:

-

Global circumferential strain

- GLS:

-

Global longitudinal strain

- GRS:

-

Global radial strain

- HARP:

-

Harmonic phase analysis

- HF:

-

Heart failure

- IQR:

-

Interquartile range

- KT:

-

Kidney transplant

- LV:

-

Left ventricle/left ventricular

- LVEDV:

-

Left ventricular end-diastolic volume

- LVEF:

-

Left ventricular ejection fraction

- LVESV:

-

Left ventricular end-systolic volume

- LVH:

-

Left ventricular hypertrophy

- LVM:

-

Left ventricular mass

- LVMi:

-

Left ventricular mass index

- NT-BNP:

-

N-terminal brain natriuretic peptide

- SPAMM:

-

Spatial modulation of magnetization

References

Foley RN, Parfrey PS, Sarnak MJ. Clinical epidemiology of cardiovascular disease in chronic renal disease. Am J Kidney Dis. 1998;32:S112–9.

Wolfe RA, Ashby VB, Milford EL, et al. Comparison of mortality in all patients on dialysis, patients on dialysis awaiting transplantation, and recipients of a first cadaveric transplant. N Engl J Med. 1999;341:1725–30.

Tonelli M, Wiebe N, Knoll G, et al. Systematic review: kidney transplantation compared with dialysis in clinically relevant outcomes. Am J Transplant. 2011;11:2093–109.

Jardine AG, Gaston RS, Fellstrom BC, Holdaas H. Prevention of cardiovascular disease in adult recipients of kidney transplants. Lancet. 2011;378:1419–27.

deFilippi C, Wasserman S, Rosanio S, et al. Cardiac troponin T and C-reactive protein for predicting prognosis, coronary atherosclerosis, and cardiomyopathy in patients undergoing long-term hemodialysis. JAMA. 2003;290:353–9.

Sharma R, Gaze DC, Pellerin D, et al. Cardiac structural and functional abnormalities in end stage renal disease patients with elevated cardiac troponin T. Heart. 2006;92:804–9.

Wang AY, Lam CW, Wang M, et al. Diagnostic potential of serum biomarkers for left ventricular abnormalities in chronic peritoneal dialysis patients. Nephrol Dial Transplant. 2009;24:1962–9.

Cochet A, Quilichini G, Dygai-Cochet I, et al. Baseline diastolic dysfunction as a predictive factor of trastuzumab-mediated cardiotoxicity after adjuvant anthracycline therapy in breast cancer. Breast Cancer Res Treat. 2011;130:845–54.

Kalam K, Otahal P, Marwick TH. Prognostic implications of global LV dysfunction: a systematic review and meta-analysis of global longitudinal strain and ejection fraction. Heart. 2014;100:1673–80.

Mordi I, Bezerra H, Carrick D, Tzemos N. The combined incremental prognostic value of LVEF, late gadolinium enhancement, and global circumferential strain assessed by CMR. JACC Cardiovasc Imaging. 2015;8:540–9.

Pi SH, Kim SM, Choi JO, et al. Prognostic value of myocardial strain and late gadolinium enhancement on cardiovascular magnetic resonance imaging in patients with idiopathic dilated cardiomyopathy with moderate to severely reduced ejection fraction. J Cardiovasc Magn Reson. 2018;20:36.

Sengelov M, Jorgensen PG, Jensen JS, et al. Global longitudinal strain is a superior predictor of all-cause mortality in heart failure with reduced ejection fraction. JACC Cardiovasc Imaging. 2015;8:1351–9.

Negishi K, Negishi T, Kurosawa K, et al. Practical guidance in echocardiographic assessment of global longitudinal strain. JACC Cardiovasc Imaging. 2015;8:489–92.

Liu YW, Su CT, Sung JM, et al. Association of left ventricular longitudinal strain with mortality among stable hemodialysis patients with preserved left ventricular ejection fraction. Clin J Am Soc Nephrol. 2013;8:1564–74.

Kramann R, Erpenbeck J, Schneider RK, et al. Speckle tracking echocardiography detects uremic cardiomyopathy early and predicts cardiovascular mortality in ESRD. J Am Soc Nephrol. 2014;25:2351–65.

Hawwa N, Shrestha K, Hammadah M, et al. Reverse remodeling and prognosis following kidney transplantation in contemporary patients with cardiac dysfunction. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2015;66:1779–87.

Lai KN, Barnden L, Mathew TH. Effect of renal transplantation on left ventricular function in hemodialysis patients. Clin Nephrol. 1982;18:74–8.

Prasad GVR, Yan AT, Nash M, et al. Determinants of left ventricular characteristics assessed by cardiac magnetic resonance imaging and cardiovascular biomarkers related to kidney transplantation. Can J Kidney Health Dis. 2018; 5:article first published online November 9, 2018.

Maceira AM, Prasad SK, Khan M, Pennell DJ. Normalized left ventricular systolic and diastolic function by steady state free precession cardiovascular magnetic resonance. J Cardiovasc Magn Reson. 2006;8:417–26.

Tee M, Noble JA, Bluemke DA. Imaging techniques for cardiac strain and deformation: comparison of echocardiography, cardiac magnetic resonance and cardiac computed tomography. Expert Rev Cardiovasc Ther. 2013;11:221–31.

Claus P, Omar AMS, Pedrizzetti G, et al. Tissue tracking Technology for Assessing Cardiac Mechanics: principles, Normal values, and clinical applications. JACC Cardiovasc Imaging. 2015;8:1444–60.

Nair V, Robinson-Cohen C, Smith MR, et al. Growth differentiation Factor-15 and risk of CKD progression. J Am Soc Nephrol. 2017;28:2233–40.

Hensen LCR, Goossens K, Delgado V, et al. Prevalence of left ventricular systolic dysfunction in pre-dialysis and dialysis patients with preserved left ventricular ejection fraction. Eur J Heart Fail. 2017;20:560-68.

Casas-Aparicio G, Castillo-Martinez L, Orea-Tejeda A, et al. The effect of successful kidney transplantation on ventricular dysfunction and pulmonary hypertension. Transplant Proc. 2010;42:3524–8.

Wali RK, Wang GS, Gottlieb SS, et al. Effect of kidney transplantation on left ventricular systolic dysfunction and congestive heart failure in patients with end-stage renal disease. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2005;45:1051–60.

Jakubovic BD, Wald R, Goldstein MB, et al. Comparative assessment of 2-dimensional echocardiography vs cardiac magnetic resonance imaging in measuring left ventricular mass in patients with and without end-stage renal disease. Can J Cardiol. 2013;29:384–90.

Kraitchman DL, Sampath S, Castillo E, et al. Quantitative ischemia detection during cardiac magnetic resonance stress testing by use of FastHARP. Circulation. 2003;107:2025–30.

Osman NF, Prince JL. Visualizing myocardial function using HARP MRI. Phys Med Biol. 2000;45:1665–82.

Yan AT, Yan RT, Cushman M, et al. Relationship of interleukin-6 with regional and global left-ventricular function in asymptomatic individuals without clinical cardiovascular disease: insights from the multi-ethnic study of atherosclerosis. Eur Heart J. 2010;31:875–82.

Kuetting D, Sprinkart AM, Doerner J, et al. Comparison of magnetic resonance feature tracking with harmonic phase imaging analysis (CSPAMM) for assessment of global and regional diastolic function. Eur J Radiol. 2015;84:100–7.

Moody WE, Taylor RJ, Edwards NC, et al. Comparison of magnetic resonance feature tracking for systolic and diastolic strain and strain rate calculation with spatial modulation of magnetization imaging analysis. J Magn Reson Imaging. 2015;41:1000–12.

Plana JC, Galderisi M, Barac A, et al. Expert consensus for multimodality imaging evaluation of adult patients during and after cancer therapy: a report from the American Society of Echocardiography and the European Association of Cardiovascular Imaging. J Am Soc Echocardiogr. 2014;27:911–39.

Kato TS, Noda A, Izawa H, et al. Discrimination of nonobstructive hypertrophic cardiomyopathy from hypertensive left ventricular hypertrophy on the basis of strain rate imaging by tissue Doppler ultrasonography. Circulation. 2004;110:3808–14.

Koyama J, Falk RH. Prognostic significance of strain Doppler imaging in light-chain amyloidosis. JACC Cardiovasc Imaging. 2010;3:333–42.

Hewing B, Dehn AM, Staeck O, et al. Improved left ventricular structure and function after successful kidney transplantation. Kidney Blood Press Res. 2016;41:701–9.

Hashimoto I, Li X, Hejmadi Bhat A, et al. Myocardial strain rate is a superior method for evaluation of left ventricular subendocardial function compared with tissue Doppler imaging. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2003;42:1574–83.

Hung CL, Verma A, Uno H, et al. Longitudinal and circumferential strain rate, left ventricular remodeling, and prognosis after myocardial infarction. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2010;56:1812–22.

Wang J, Khoury DS, Yue Y, et al. Preserved left ventricular twist and circumferential deformation, but depressed longitudinal and radial deformation in patients with diastolic heart failure. Eur Heart J. 2008;29:1283–9.

Mizuguchi Y, Oishi Y, Miyoshi H, et al. The functional role of longitudinal, circumferential, and radial myocardial deformation for regulating the early impairment of left ventricular contraction and relaxation in patients with cardiovascular risk factors: a study with two-dimensional strain imaging. J Am Soc Echocardiogr. 2008;21:1138–44.

Zhang Q, Fung JW, Yip GW, et al. Improvement of left ventricular myocardial short-axis, but not long-axis function or torsion after cardiac resynchronisation therapy: an assessment by two-dimensional speckle tracking. Heart. 2008;94:1464–71.

Delgado V, Ypenburg C, Zhang Q, et al. Changes in global left ventricular function by multidirectional strain assessment in heart failure patients undergoing cardiac resynchronization therapy. J Am Soc Echocardiogr. 2009;22:688–94.

Klimusina J, De Boeck BW, Leenders GE, et al. Redistribution of left ventricular strain by cardiac resynchronization therapy in heart failure patients. Eur J Heart Fail. 2011;13:186–94.

Mahmod M, Bull S, Suttie JJ, et al. Myocardial steatosis and left ventricular contractile dysfunction in patients with severe aortic stenosis. Circ Cardiovasc Imaging. 2013;6:808–16.

Edwards NC, Hirth A, Ferro CJ, et al. Subclinical abnormalities of left ventricular myocardial deformation in early-stage chronic kidney disease: the precursor of uremic cardiomyopathy? J Am Soc Echocardiogr. 2008;21:1293–8.

Burton JO, Jefferies HJ, Selby NM, McIntyre CW. Hemodialysis-induced cardiac injury: determinants and associated outcomes. Clin J Am Soc Nephrol. 2009;4:914–20.

Foley RN, Curtis BM, Randell EW, Parfrey PS. Left ventricular hypertrophy in new hemodialysis patients without symptomatic cardiac disease. Clin J Am Soc Nephrol. 2010;5:805–13.

Glassock RJ, Pecoits-Filho R, Barberato SH. Left ventricular mass in chronic kidney disease and ESRD. Clin J Am Soc Nephrol. 2009;4(Suppl 1):S79–91.

Wald R, Yan AT, Perl J, et al. Regression of left ventricular mass following conversion from conventional hemodialysis to thrice weekly in-Centre nocturnal hemodialysis. BMC Nephrol. 2012;13:3.

Vaidya OU, House JA, Coggins TR, et al. Effect of renal transplantation for chronic renal disease on left ventricular mass. Am J Cardiol. 2012;110:254–7.

Young JB, Neumayer HH, Gordon RD. Pretransplant cardiovascular evaluation and posttransplant cardiovascular risk. Kidney Int Suppl. 2010:S1–7.

Weisensee D, Low-Friedrich I, Riehle M, et al. In vitro approach to 'uremic cardiomyopathy'. Nephron. 1993;65:392–400.

Aoki J, Ikari Y, Nakajima H, et al. Clinical and pathologic characteristics of dilated cardiomyopathy in hemodialysis patients. Kidney Int. 2005;67:333–40.

Vanholder R, Glorieux G, Lameire N, European Uremic Toxin Work Group. Uraemic toxins and cardiovascular disease. Nephrol Dial Transplant. 2003;18:463–6.

Zoccali C, Bode-Boger S, Mallamaci F, et al. Plasma concentration of asymmetrical dimethylarginine and mortality in patients with end-stage renal disease: a prospective study. Lancet. 2001;358:2113–7.

Acknowledgements

This study was funded by the Heart and Stroke Foundation of Canada, Grant Number HSFNA7077. Dr. Kim A Connelly is supported by a New Investigator award from the CIHR and an Early Researcher award from the Ministry of Ontario. Dr. Yan is supported by a Clinician-Scientist Award from the University of Toronto. Dr. Lakshman Gunaratnam is supported by Schulich New Investigator Award, Schulich School of Medicine and Dentistry, Western University and the KRESCENT/CIHR New Investigator Award.

Funding

This study was funded by the Heart and Stroke Foundation of Canada, Grant Number HSFNA7077. Dr. Kim A Connelly is supported by a New Investigator award from the CIHR and an Early Researcher award from the Ministry of Ontario. Dr. Yan is supported by a Clinician-Scientist Award from the University of Toronto. Dr. Lakshman Gunaratnam is supported by Schulich New Investigator Award, Schulich School of Medicine and Dentistry, Western University and the KRESCENT/CIHR New Investigator Award.

Availability of data and materials

The datasets generated and/or analysed during the current study are not publicly available due to privacy agreements but are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

IYG Study conception and design, data analysis and interpretation, drafting and revision of the manuscript. BA Study conception and design, data analysis and interpretation, revision of the manuscript. RP Data interpretation, manuscript revision. PWC Data analysis and interpretation, manuscript revision. RMW Data analysis and interpretation, manuscript revision. RW Data analysis and interpretation, manuscript revision. DPD Data analysis and interpretation, manuscript revision. HLP Data analysis and interpretation, manuscript revision. MMN Study conception and design, manuscript revision. WY Study conception and design, manuscript revision. LG Data analysis and interpretation, manuscript revision. JK Data analysis and interpretation, manuscript revision. CL Data analysis and interpretation, manuscript revision. KAC Study conception and design, data analysis and interpretation, manuscript revision. ATY Study conception and design, data analysis and interpretation, manuscript revision. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

All study participants provided written informed consent. The study was approved by the research ethics boards of St. Michael’s Hospital, Toronto General Hospital, and London Health Sciences Centre.

Consent for publication

Not applicable

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Additional file

Additional file 1:

Figure S1. Scatter plot of the correlation between baseline global longitudinal strain and left ventricular mass indexed to body surface area. (DOCX 4798 kb)

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made. The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver (http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/) applies to the data made available in this article, unless otherwise stated.

About this article

Cite this article

Gong, I.Y., Al-Amro, B., Prasad, G.R. et al. Cardiovascular magnetic resonance left ventricular strain in end-stage renal disease patients after kidney transplantation. J Cardiovasc Magn Reson 20, 83 (2018). https://doi.org/10.1186/s12968-018-0504-5

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s12968-018-0504-5