Abstract

Background

Scar burden by late gadolinium enhancement (LGE) cardiovascular magnetic resonance (CMR) is associated with functional recovery after coronary artery bypass surgery (CABG). There is limited data on long-term mortality after CABG based on left ventricular (LV) scar burden.

Methods

Patients who underwent LGE CMR between January 2003 and February 2010 within 1 month prior to CABG were included. A standard 16 segment model was used for scar quantification. A score of 1 for no scar, 2 for ≤ 50 % and 3 for > 50 % transmurality was assigned for each segment. LV scar score (LVSS) defined as the sum of segment scores divided by 16. All-cause mortality was ascertained by social security death index.

Results

One hundred ninety-six patients met the inclusion criteria. 185 CMR studies were available. History of prior MI was present in 64 % and prior CABG in 5.4 % of patients. Scar was present in 72 % of patients and median LVEF was 38 %. Over a median follow up of 8.3 years, there were 64 deaths (34.6 %). There was no statistically significant difference in mortality between Scar and No-scar groups (37 % versus 29 %). In the group with scar, a lower scar burden (defined either < 4 segments with scar or based on LVSS) was independently associated with increased survival.

Conclusion

In patients undergoing surgical revascularization, scar burden is negatively associated with survival in patients with scar. However, there is no difference in survival based on presence or absence of scar alone. CMR prior to CABG adds additional prognostic information.

Similar content being viewed by others

Background

Coronary artery bypass graft surgery (CABG) is one of the most common cardiac surgeries performed worldwide. The decision for surgical revascularization is based on several factors including patient characteristics, coronary anatomy and presence of ischemia or infarct. Cardiovascular Magnetic Resonance (CMR) is considered gold standard for assessment of fibrosis/scar and is commonly used in evaluation of patients with significant coronary artery disease (CAD) and cardiomyopathy prior to formulating treatment strategy.

Assessment of size and extent of scar or fibrosis by Late Gadolinium Enhancement (LGE) by CMR is accurate and reproducible [1–5]. The presence and amount of LGE is an independent predictor of cardiovascular outcomes and mortality in patients with ischemic heart failure (HF) and non-ischemic cardiomyopathies (NICM) [6–8]. LGE is effective in detection and assessment of both acute and chronic myocardial infarction (MI) and is well matched to the perfusion territory of infarct related artery [9]. In patients with CAD, LGE is a predictor of major adverse cardiac events (MACE) and mortality beyond common clinical factors or coronary anatomy and is independent of left ventricular ejection fraction (LVEF) [10–13].

In ischemic HF, the transmurality of the scar is negatively associated with functional recovery. Segments with > 50 % scar have a low probability of functional recovery [14–16]. The presence of ≥ 10 segments without scar or with <50 % transmural scar predicted a global functional recovery in one study [17] while the presence of ≤4 scar segments predicted global functional recovery after CABG in another study [18]. In patient with ischemic HF observational studies support improved survival with CABG over medical therapy during 10 year follow up [19, 20] while a more recent randomized study showed a reduction in cardiac mortality but no difference in all-cause mortality [21, 22]. In a cohort of patients treated with CABG, the presence of larger end systolic volume index and scar burden on CMR was noted to derive survival benefit compared to treatment with medical therapy alone [23].

While there is data to support functional improvement post revascularization, there is limited data in the use of CMR in outcomes after revascularization. In this study, we evaluated the association between LGE burden and long-term mortality after CABG.

Methods

Patients who underwent CMR with LGE between January 2003 and February 2010 within 1 month prior to CABG surgery were included.

A comprehensive surgical database maintained at our institution was accessed to obtain demographic, clinical and surgical information. Angiographic data including major and branch vessel stenosis was collected. All-cause mortality was ascertained by social security death index search.

CMR protocol and analysis

Patients were positioned supine in a clinical 1.5 T MR scanner (CV Intera, Philips, Best, The Netherlands). All images were acquired using a cardiac phased-array receiver coil during breath-holds (≈8 s), together with respiratory and cardiac gating. Cine images were acquired through the entire left ventricle using 6-mm-thick slices to minimize the effects of partial volume. LGE images were obtained after intra venous contrast agent administration (0.2 mmol/kg gadolinium dimeglumine, until July 2006, then 0.1 mmol/kg gadobenate dimegluine) [2] using a segmented inversion-recovery sequence, with an in-plane spatial resolution of 1.3 to 1.7 mm [1].

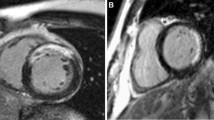

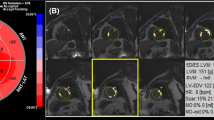

Evaluation of CMR and post-processing were performed on a commercially available workstation (View Forum, Philips Medical Systems). End-diastolic and end-systolic cardiac contours were traced manually on the series of LV short-axis cine slices to obtain LVEF and LV volumes. Scar quantification was performed by image review by an experienced observer who was blinded from clinical analysis and prior CMR reading. Based on the prior data on functional improvement after revascularization in patients with LGE by CMR, a simplified quantification method was used. Left ventricular (LV) was divided into a standard 16 segment model (6 basal, 6 mid and 4 apical segments) for quantification of scar. The number of segments with scar was recorded. Each segment was then scored based on scar transmurality. Segment was assigned a score of 1 for no scar, 2 for ≤50 % thickness, and 3 for > 50 % thickness or micro vascular obstruction (MVO) (Fig. 1). Subjects were divided into <4 segments of scar (group A) and ≥4 segments of scar (group B). LV scar score (LVSS) was calculated by the sum of the scores of all segments divided by 16 [10] (a LVSS of 1 would represent no scar).

Statistical analysis

Data analysis was performed using SAS 9.3 Institute Inc., Cary, NC, USA. Categorical variables were presented as proportions and analyzed with Chi square test (Fisher’s exact test was used in case of small numbers). For comparison between continuous variables two sample t- test was used. Non-parametric Wilcoxon rank sum test was used in case of non-normal variables. Univariate and multivariate analysis was performed with Cox proportional hazard model. Multivariate analysis was performed using variables that have significant association in the bivariate analysis. Survival probability was plotted with Kaplan Meier curves (Log rank test). A value of p < 0.05 was considered statistically significant.

Results

One hundred ninety-six patients met the inclusion criteria. 185 CMR studies were available. The median time from CMR study to CABG surgery was 2 (1, 4) days. The mean age of the study population at the time of surgery was 63.2 years (±11.5). Seventy-two percent were male and 66 % were Caucasians. History of prior MI was present in 64 % of patients and prior CABG in 5.4 % patients. All patients in the study group had significant stenosis (≥70 %) in at least one major epicardial vessel. There was a median of 2 (1,3) significantly stenosed vessels and 1 (0,1) total occlusions. All patients were deemed appropriate for CABG as the revascularization strategy by the angiographer and patient’s cardiologist due to the presence of complex coronary artery disease. A median of 4 (3, 4) vessels (major or branch vessels) were bypassed. Scar was present in 72 % of patients and median LVEF was 38 % (28, 52). Over a median follow up of 8.3 years (7, 10), there were 64 deaths (34.6 %) in the entire group.

Patients were categorized into Scar group and No-scar groups. Scar group was further categorized into two groups based on the number of segments with scar (<4 segments versus ≥4 segments with scar) and also into three groups based on LV scar score (LVSS 1–1.24, LVSS 1.25–1.42 and LVSS >1.42).

Scar versus No-scar group

There were 133 patients in the scar group and 52 patients in the No-scar group. The baseline characteristics are shown in Table 1. Patients in Scar group had statistically higher proportion of men (78 % vs. 56 % (p = 0.002)), history of prior MI (74 % vs. 38 % (p < 0.0001)) and lower percent LVEF (39 % versus 45 % (p = 0.038)) compared to patients in the No-scar group. During the follow up there was no statistically significant difference (Fig. 2) in long-term mortality between Scar and No-scar groups (37 % versus 29 %, p = 0.47)

Scar group analysis

Less than 4 segments scar group (A) versus ≥ 4 segments scar group (B)

The baseline characteristics (Table 2) were similar except that patients in group B had a higher proportion of history of prior CABG (14 % vs. 1.5 % p = 0.009) and lower proportion of history of ACE inhibitor usage (47 % versus 70 % (p = 0.0066)) compared to patients in group A. There was no statistically significant difference in STS scores or LVEF between the two groups. The median number of segments of LGE was 2 (1, 3) for patients in group A vs. 6 (5, 7) in group B. The number of trans mural segments was 1(0,2) vs. 2(1,5), p < 0.0001) and the LVSS was 1.2(1.1,1.3) vs. 1.5(1.4,1.7) p < 0.0001) in group A vs. group B respectively. During the follow up 27 % patients died in group A vs. 47 % group B (p = 0.02).

In a univariate analysis (Table 3) Age, LVEF, Female gender, presence of peripheral artery disease (PAD), GFR, and Scar group (A vs. B), number of segments of scar, number of transmural segments and LVSS were all significantly associated with long-term mortality. In multivariate analysis (Table 4) Scar group B was independently associated with long-term mortality (p = 0.018, HR = 2.0 (1.1–3.7). Age, LVEF and GFR were also independently associated with long-term mortality. Survival (Fig. 3) was significantly lower in group B compared to group A (p = 0.038)

LV scar score and long-term mortality

Number of segments of scar (p = 0.005, HR = 1.16 CI = 1.05–1.28), Number of Trans mural segments (p = 0.001, HR = 1.2 CI = 1.07–1.33) and LVSS (p = 0.0008, HR = 4.9 CI = 1.9–12.3) were independently associated with long-term mortality. Groups based on LVSS (LVSS 1–1.24 (n = 44), LVSS 1.25–1.42 (n = 43), and LVSS >1.42 (n = 46)) had significantly different survival probabilities (Fig. 4) during the follow up (p = 0.026), favoring smaller LVSS.

Discussion

To the best of our knowledge this is the longest survival follow up after CMR and CABG stratified based on scar burden. Data was retrievable in 94.4 % of our study population accurately. The study population had a long-term mortality of 35 % over a period of 8.3 years. In prior studies including patients with ischemic cardiomyopathy (EF 26–29 %) and CABG, mortality ranged from 29–58 % over 10 years [19, 20]. In previous studies, patients with ischemic HF who had CMR, mortality was 15 % over a follow up of 2.6 years [10] and 41 % over a follow up of 5.8 years [23]. Our patient group had a moderately reduced LVEF (median 38 %), an increased prevalence of prior MI, and a longer follow up with comparable mortality to prior studies.

In our study, there was no significant difference in survival based on presence or absence of scar. The most common reason for ordering CMR prior to formulating treatment strategy in patients with angiographically significant CAD is for assessment of scar/viability. Myocardial viability however, is a complex and incompletely understood phenomenon. In clinical practice, the presence of visually significant CAD on angiography in patients with cardiomyopathy is equated as ischemic cardiomyopathy. Previous studies on patients with ischemic versus non-ischemic cardiomyopathies have shown that the extent of CAD is the most predictive feature of prognosis [24]. However, this may not be the case in all patients, and in a subgroup of patients with obstructive CAD, there may be a concomitant non-ischemic etiology for cardiomyopathy. CMR may be useful in identifying this subgroup. In our study, patients with no scar had significantly lower prevalence of prior MI as well as a lower median number of totally occluded major epicardial arteries compared to the scar group. While no scar on CMR may indicate that all segments are viable in these patients, it may alternately suggest a non-ischemic cardiomyopathy as the primary etiology. This may suggest the need for further analysis to prove ischemia in this group of patients undergoing CABG, and further study of non-scar patients to evaluate them for intrinsic myocardial abnormalities. The current study is limited by ischemia data acquired before the clinical decision for CABG was made and the control arm to identify the subgroup of patients with in the no scar group that may have benefited from revascularization.

In the scar group patients, a higher scar burden is negatively associated with survival despite CABG. Several factors could explain this. Prior studies suggested that there could be a scar threshold beyond which the benefits of revascularization are attenuated. It is possible that patients with large amount of scar in the revascularized territory may actually not have significant viable tissue that can be recovered. In addition, previous studies have shown that myocardial scar size and characteristics predict spontaneous ventricular arrhythmias in patients with an ischemic cardiomyopathy [25–28] which can result in worse survival independent of LV functional improvement. In this study we have used several easily reproducible parameters to assess scar burden. Number of segments of scar and number of segments with significant transmurality of scar are easy to measure and are independently associated with long term mortality, but they may have potential for underestimating and sometimes overestimating global scar burden. To overcome this we have used LV scar score, another parameter which is easy to measure and a better index of global scar burden. LVSS also is independently associated with survival. While the scar group was subdivided based on study sample size and previously available data, it is somewhat arbitrary. However, the overall study results in the entire scar group strongly suggest a worse prognosis with increased scar burden. The favorable prognosis of patients with small scar burden likely represents patients with proven ischemic CM who then obtain the full benefit of revascularization.

Clinical implications

Multiple prior studies suggest worse outcomes and survival in patients with LGE on CMR. There is data to support functional improvement after CABG [15–18]. CABG aims to improve symptoms, LVEF, MACE and prolong survival by reducing ischemia. Data from observational studies suggest significant survival advantage from CABG over medical therapy in this patient population. The STICH (Surgical Treatment For Ischemic heart failure) study failed to show improvement in all-cause mortality but there was a decrease in cardiovascular death with CABG [21]. LGE on CMR provides unique long-term prognostic information after CABG, independent of traditional predictors. Randomized studies comparing therapeutic alternatives using CMR viability data would be needed to determine the utility of this information in deciding on treatment strategy. The study used simplified quantification tools to calculate fibrosis burden based on prior published data, to allow a quick and day to day estimation of LGE and prognostication in clinical medicine.

Study limitations

There are several limitations for this study. This study is a retrospective observational design at a single center. As patients were referred by treating physicians, there could be potential for referral bias in a tertiary care setting and thus the results may not be generalized to all patients undergoing CABG. Patients, in whom the treating physician favored medical therapy after reviewing the CMR results, likely those with large scar area, would not have been evaluated in this study leading to a selection bias. The data on ischemia is not available in these patients which could have added more clarity to the outcomes in different subgroups. The currently ongoing Ischemia study may provide more understanding in this regard. Change of contrast agent during the study period could potentially effect the LGE quantification; however, to the best of our knowledge this effect is minimal and is uniform between different subgroups in the study. Cause of death was not identified in our study. While it is possible that deaths could have occurred from non-cardiovascular causes, we believe that it is more meaningful to study all-cause mortality for patient outcomes. In addition, retrospective identification of cause of death can be highly inaccurate and can adversely affect interpretation of results [29]. Data was not available in 5.6 % of the study group patients and is unlikely to alter the results of the study.

Conclusions

In patients undergoing CABG for significant CAD and have myocardial scar by CMR, the amount of scar is negatively associated with survival, independent of traditional predictors. Patients with significant CAD but without CMR evidence of MI had no statistically significant difference in survival after CABG compared to those with scar.

Abbreviations

ACE, angiotensin convertase enzyme; BMI, body mass index; CABG, coronary artery bypass graft surgery; CAD, coronary artery disease; CMR, cardiovascular magnetic resonance; ESVi, end systolic volume index; HF, heart failure; LGE, late gadolinium enhancement; LV, left ventricular; LVEDV, left ventricular end diastolic volume; LVEF, left ventricular ejection fraction; LVEF, left ventricular ejection fraction; LVESV, Left ventricular end systolic volume; LVSS, left ventricular scar score; MACE, major adverse cardiac events; MI, myocardial infarction; MVO, micro vascular obstruction; NICM, non‐ischemic cardiomyopathy; PAD, peripheral artery disease; STICH surgical treatment for ischemic heart failure; STS, society of thoracic surgery

References

Simonetti OP, Kim RJ, Fieno DS, Hillenbrand HB, Wu E, Bundy JM, Finn JP, Judd RM. An improved mr imaging technique for the visualization of myocardial infarction1. Radiology. 2001;218:215–23.

Wu E, Judd RM, Vargas JD, Klocke FJ, Bonow RO, Kim RJ. Visualisation of presence, location, and transmural extent of healed q-wave and non-q-wave myocardial infarction. The Lancet. 2001;357:21–8.

Mahrholdt H, Wagner A, Holly TA, Elliott MD, Bonow RO, Kim RJ, Judd RM. Reproducibility of chronic infarct size measurement by contrast-enhanced magnetic resonance imaging. Circulation. 2002;106:2322–7.

Kim RJ, Fieno DS, Parrish TB, Harris K, Chen EL, Simonetti O, Bundy J, Finn JP, Klocke FJ, Judd RM. Relationship of mri delayed contrast enhancement to irreversible injury, infarct age, and contractile function. Circulation. 1999;100:1992–2002.

Amado LC, Gerber BL, Gupta SN, Rettmann DW, Szarf G, Schock R, Nasir K, Kraitchman DL, Lima JA. Accurate and objective infarct sizing by contrast-enhanced magnetic resonance imaging in a canine myocardial infarction model. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2004;44:2383–9.

Assomull RG, Prasad SK, Lyne J, Smith G, Burman ED, Khan M, Sheppard MN, Poole-Wilson PA, Pennell DJ. Cardiovascular magnetic resonance, fibrosis, and prognosis in dilated cardiomyopathy. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2006;48:1977–85.

Wu KC, Weiss RG, Thiemann DR, Kitagawa K, Schmidt A, Dalal D, Lai S, Bluemke DA, Gerstenblith G, Marbán E, Tomaselli GF, Lima JAC. Late gadolinium enhancement by cardiovascular magnetic resonance heralds an adverse prognosis in nonischemic cardiomyopathy. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2008;51:2414–21.

Lehrke S, Lossnitzer D, Schob M, Steen H, Merten C, Kemmling H, Pribe R, Ehlermann P, Zugck C, Korosoglou G, Giannitsis E, Katus HA. Use of cardiovascular magnetic resonance for risk stratification in chronic heart failure: Prognostic value of late gadolinium enhancement in patients with non-ischaemic dilated cardiomyopathy. Heart. 2010;97:727–32.

Kim RJ, Albert TSE, Wible JH, Elliott MD, Allen JC, Lee JC, Parker M, Napoli A, Judd RM. Performance of delayed-enhancement magnetic resonance imaging with gadoversetamide contrast for the detection and assessment of myocardial infarction: An international, multicenter, double-blinded, randomized trial. Circulation. 2008;117:629–37.

Kwon DH, Halley CM, Carrigan TP, Zysek V, Popovic ZB, Setser R, Schoenhagen P, Starling RC, Flamm SD, Desai MY. Extent of left ventricular scar predicts outcomes in ischemic cardiomyopathy patients with significantly reduced systolic function. JACC Cardiovasc Imaging. 2009;2:34–44.

Cheong BYC, Muthupillai R, Wilson JM, Sung A, Huber S, Amin S, Elayda MA, Lee VV, Flamm SD. Prognostic significance of delayed-enhancement magnetic resonance imaging: Survival of 857 patients with and without left ventricular dysfunction. Circulation. 2009;120:2069–76.

Kwong RY, Chan AK, Brown KA, Chan CW, Reynolds HG, Tsang S, Davis RB. Impact of unrecognized myocardial scar detected by cardiac magnetic resonance imaging on event-free survival in patients presenting with signs or symptoms of coronary artery disease. Circulation. 2006;113:2733–43.

Bello D, Einhorn A, Kaushal R, Kenchaiah S, Raney A, Fieno D, Narula J, Goldberger J, Shivkumar K, Subacius H, Kadish A. Cardiac magnetic resonance imaging: Infarct size is an independent predictor of mortality in patients with coronary artery disease. Magn Reson Imaging. 2011;29:50–6.

McCrohon JA, Moon JC, Prasad SK, McKenna WJ, Lorenz CH, Coats AJ, Pennell DJ. Differentiation of heart failure related to dilated cardiomyopathy and coronary artery disease using gadolinium-enhanced cardiovascular magnetic resonance. Circulation. 2003;108:54–9.

Selvanayagam JB, Kardos A, Francis JM, Wiesmann F, Petersen SE, Taggart DP, Neubauer S. Value of delayed-enhancement cardiovascular magnetic resonance imaging in predicting myocardial viability after surgical revascularization. Circulation. 2004;110:1535–41.

Kim RJ, Wu E, Rafael A, Chen E-L, Parker MA, Simonetti O, Klocke FJ, Bonow RO, Judd RM. The use of contrast-enhanced magnetic resonance imaging to identify reversible myocardial dysfunction. N Engl J Med. 2000;343:1445–53.

Pegg TJ, Selvanayagam JB, Jennifer J, Francis JM, Karamitsos TD, Dall'Armellina E, Smith KL, Taggart DP, Neubauer S. Prediction of global left ventricular functional recovery in patients with heart failure undergoing surgical revascularisation, based on late gadolinium enhancement cardiovascular magnetic resonance. J Cardiovasc Magn Reson. 2010;12:56.

Yang T, Lu MJ, Sun HS, Tang Y, Pan SW, Zhao SH. Myocardial scar identified by magnetic resonance imaging can predict left ventricular functional improvement after coronary artery bypass grafting. PLoS One. 2013;8:e81991.

Velazquez EJ, Williams JB, Yow E, Shaw LK, Lee KL, Phillips HR, O'Connor CM, Smith PK, Jones RH. Long-term survival of patients with ischemic cardiomyopathy treated by coronary artery bypass grafting versus medical therapy. Ann Thorac Surg. 2012;93:523–30.

O’Connor CM, Velazquez EJ, Gardner LH, Smith PK, Newman MF, Landolfo KP, Lee KL, Califf RM, Jones RH.. Comparison of coronary artery bypass grafting versus medical therapy on long-term outcome in patients with ischemic cardiomyopathy (a 25-year experience from the duke cardiovascular disease databank). Am J Cardiol. 2002;90:101–7.

Velazquez EJ, Lee KL, Deja MA, Jain A, Sopko G, Marchenko A, Ali IS, Pohost G, Gradinac S, Abraham WT, Yii M, Prabhakaran D, Szwed H, Ferrazzi P, Petrie MC, O'Connor CM, Panchavinnin P, She L, Bonow RO, Rankin GR, Jones RH, Rouleau J-L. Coronary-artery bypass surgery in patients with left ventricular dysfunction. N Engl J Med. 2011;364:1607–16.

Carson P, Wertheimer J, Miller A, O'Connor CM, Pina IL, Selzman C, Sueta C, She L, Greene D, Lee KL, Jones RH, Velazquez EJ. The stich trial (surgical treatment for ischemic heart failure). JACC: Heart Failure. 2013;1:400–8.

Kwon DH, Hachamovitch R, Popovic ZB, Starling RC, Desai MY, Flamm SD, Lytle BW, Marwick TH. Survival in patients with severe ischemic cardiomyopathy undergoing revascularization versus medical therapy: Association with end-systolic volume and viability. Circulation. 2012;126:S3–8.

Bart BA, Shaw LK, McCants Jr CB, Fortin DF, Lee KL, Califf RM, O’Connor CM. Clinical determinants of mortality in patients with angiographically diagnosed ischemic or nonischemic cardiomyopathy. J Am Coll Cardiol. 1997;30:1002–8.

Demirel F, Adiyaman A, Timmer JR, Dambrink J-HE, Kok M, Boeve WJ, Elvan A. Myocardial scar characteristics based on cardiac magnetic resonance imaging is associated with ventricular tachyarrhythmia in patients with ischemic cardiomyopathy. Int J Cardiol. 2014;177:392–9.

de Haan S, Meijers TA, Knaapen P, Beek AM, van Rossum AC, Allaart CP. Scar size and characteristics assessed by cmr predict ventricular arrhythmias in ischaemic cardiomyopathy: Comparison of previously validated models. Heart. 2011;97:1951–6.

Scott PA, Morgan JM, Carroll N, Murday DC, Roberts PR, Peebles CR, Harden SP, Curzen NP. The extent of left ventricular scar quantified by late gadolinium enhancement mri is associated with spontaneous ventricular arrhythmias in patients with coronary artery disease and implantable cardioverter-defibrillators. Circ Arrhythm Electrophysiol. 2011;4:324–30.

Alexandre J, Saloux E, Dugue AE, Lebon A, Lemaitre A, Roule V, Labombarda F, Provost N, Gomes S, Scanu P, Milliez P. Scar extent evaluated by late gadolinium enhancement cmr: A powerful predictor of long term appropriate icd therapy in patients with coronary artery disease. J Cardiovasc Magn Reson. 2013;15:12.

Lauer MS, Blackstone EH, Young JB, Topol EJ. Cause of death in clinical researchtime for a reassessment? J Am Coll Cardiol. 1999;34:618–20.

Acknowledgments

Dr. Eiman Jahangir MD, Ruben Hernaez MD and Core lab for statistical assistance.

Funding

No source of funding.

Availability of supporting data

Not applicable.

Authors’ contributions

KrK, AE, KaK, SS, AF carried out data collection and writing manuscript. GW carried out data collection, analysis of results and writing manuscript. PH, SB carried out data collection. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Ethics approval and consent to participate

This retrospective study was approved by the MedStar institutional review board with waiver of individual consent.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made. The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver (http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/) applies to the data made available in this article, unless otherwise stated.

About this article

Cite this article

Kancharla, K., Weissman, G., Elagha, A.A. et al. Scar quantification by cardiovascular magnetic resonance as an independent predictor of long-term survival in patients with ischemic heart failure treated by coronary artery bypass graft surgery. J Cardiovasc Magn Reson 18, 45 (2016). https://doi.org/10.1186/s12968-016-0265-y

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s12968-016-0265-y