Abstract

Background

Tapasin is a crucial component of the major histocompatibility (MHC) class I antigen presentation pathway. Defects in this pathway can lead to tumor immune evasion. The aim of this study was to test whether tapasin expression correlates with CD8+ cytotoxic T lymphocyte (CTL) infiltration of colorectal cancer (CRC) and overall survival.

Methods

A next-generation tissue microarray (ngTMA) of 198 CRC patients with full clinicopathological information was included in this study. TMA slides were immunostained for tapasin, MHC I and CD8. Marker expression was analyzed with immune-cell infiltration, patient survival and TNM-staging.

Results

A reduction of tapasin expression strongly correlated with venous invasion (AUC 0.682, OR 2.7, p = 0.002; 95 % CI 1.7–5.0), lymphatic invasion (AUC 0.620, OR 2.0, p = 0.005; 95 % CI 1.3–3.3), distant metastasis (AUC 0.727, OR 2.9, p = 0.004; 95 % CI 1.4–5.9) and an infiltrative tumor border configuration (AUC 0.621, OR 2.2, p = 0.017; 95 % CI 1.2–4.4). Further, tapasin expression was associated with CD8+ CTL infiltration (AUC 0.729, OR 5.4, p < 0.001; 95 % CI 2.6–11), and favorable overall survival (p = 0.004, HR 0.6, 95 % CI 0.42–0.85).

Conclusions

Consistent with published functional data showing that tapasin promotes antigen presentation, as well as tumor immune recognition and destruction by CD8+ CTLs, a reduction in tapasin expression is associated with tumor progression in CRC.

Similar content being viewed by others

Background

The ability of the immune system to recognize and attack tumor cells is being acknowledged as an increasingly important factor in overall disease progression [1–3]. Specifically, in colorectal cancer (CRC), increased tumor infiltration by CD4+ and CD8+ T-lymphocytes (CTLs) correlates positively with overall (OS) and disease-free survival (DFS) [2].The surface presentation of antigenic peptides by the Major Histocompatibility Complex class I molecules (MHC I) is indispensable for the initiation of the CD8+ T-lymphocyte anti-tumoral immune response. The MHC I consists of the heavy α-chain (HLA) and a β2-microglobulin (B2M) chain. Folding and assembly is assisted by the chaperone calnexin. The antigenic peptides are generated by the proteasome and loaded into the assembled MHC I molecule through a multi-step process involving (1) translocation of the peptides into the endoplasmic reticulum by TAP1/2 proteins, and (2) binding of the peptides to assembled MHC I molecules facilitated by the peptide loading complex (TAP1, TAP2, calreticulin, ERp57 and tapasin). A conformational change in the molecule resulting from peptide binding releases the MHC I from the loading complex and allows surface presentation of the antigen [4, 5].

Tapasin is an essential member of the MHC I pathway. On a molecular level, it is a transmembrane glycoprotein which forms a stable heterodimer with the thiol oxidoreductase ERp57 [6]. Cells missing tapasin have reduced MHC I surface expression [7], and display MHC I molecules loaded with suboptimal, low affinity peptides [8], resulting in decreased CTL recognition [9]. Loss of tapasin therefore contributes to reduced immunogenicity and immune evasion of tumors [10]. The importance of tapasin for antigen presentation in cancer was first shown in vivo in mouse tumor models. Mice were injected with a lung carcinoma cell line in which many components of the MHC I pathway were downregulated. Transfection of tapasin on this background was sufficient to restore antigen presentation, increase the antigen-specific immune response, reduce tumor growth, and increase survival [11]. However, the potential effect of tapasin on patient outcome in human CRC has not been determined to date. The aim of this study was therefore to test whether tapasin expression correlates with the degree of CTL infiltration and overall survival in CRC and thus influences overall survival.

Methods

Patients

This study was designed to comply with the reporting recommendations for tumor marker prognostic studies (REMARK) guidelines for tumor marker prognostic studies. The study design is shown in Additional file 1: Figure S1. 220 non-consecutive surgically treated CRC patients treated from 2004 to 2007 at the Areteiaion University Hospital, University of Athens, Greece, were retrospectively included in this study. Clinical data were obtained from patient records including patient age at diagnosis, gender, tumor location and diameter, and overall survival time. An experienced GI pathologist (EK) reviewed all histomorphological data of the surgical resections, and recorded data on pTNM classification, tumor grade, lymphatic and venous invasion, histological subtype and tumor border configuration. Clinicopathological features of the 198 patients for which tapasin expression could be analyzed are listed in Additional file 2: Table S1. The median survival time was 58 months (95 % CI 50.9–65.1 month). Detailed clinicopathological data for this cohort has been published [12]. The use of patient data has been approved by the local Ethics Committee of the University of Athens, Greece.

Assay methods

Using a digital pathology and automated tissue microarraying approach, a next-generation tissue microarray (ngTMA [13]) was constructed that included tissue spots from the tumor center (n = 2), tumor front (n = 2) and matched normal colorectal mucosa (n = 1) from 220 patients [13]. The ngTMA blocks were sectioned at 4 µm and stained for MHC I with an established antibody [14] that detects the main human HLA types A, B and C (Abcam #ab70328, dilution 1:4000, pre-treatment citrate 30′, 100 °C), for tapasin (Novus #NBP1-86968, dilution 1:50, pre-treatment tris 30′, 95 °C) and CD8 (Dako, #M7103, dilution 1:100, pre-treatment tris 20′, 90 °C) by automated immunohistochemistry using a standard protocol on a LEICA Bond-III.

Evaluation of immunohistochemistry

To detect the MHC I complex, we evaluated the percentage of cells which showed membranous expression of the classical heavy α-chain isoforms (HLA-ABC) in relation to the total number of cells in the spot under high power (400×) magnification. The expression varied between 0 and 100 percent, with the median and mean scores being 30 and 23.8, respectively. Intratumoral lymphocytes and normal mucosa served as an internal positive control. CD8+ CTLs were counted in each spot. Because tapasin is ubiquitously expressed, immunoreactivity was assessed by scoring the staining intensity. The intensity was scored as 0–3, with 0 representing complete absence of marker reactivity, 1 as low staining intensity visible at 200×, 2 as medium staining intensity visible at 100×, 3 as high staining intensity visible at all magnifications, based on an adaptation of the well-established protocol for the assessment of HER2 biomarker expression by Rüschoff and colleagues [15]. The expression varied between 0 and 3 with the median and mean scores being 2.31 and 2.33, respectively. Normal mucosa served as an internal positive control.

Statistics

The association of protein markers with clinicopathological features was analyzed by receiver operating characteristic (ROC) curve analysis and logistic regression. The p values, odds ratios (OR) and 95 % CI for each analysis were obtained, as well as the area under the curve (AUC), with values closer to 1 indicating a better discriminatory ability for binary end point. For survival assessment using non-dichotomized data, Cox regression analyses were performed. After verification of the proportional hazards assumption, multivariable Cox regression analysis was carried out using pT (primary tumor), pN (regional lymph nodes), pM (distant metastasis), adjuvant therapy (postoperative therapy, such as chemotherapy, radiotherapy or combination therapies), CD8+ CTL infiltration and protein expression as possible confounding factors. Hazard ratios (HR) and 95 % CI were used to determine the effect size. Differences in survival time were displayed using standard Kaplan–Meier curves and tested using the log-rank test in univariate analysis. The time of survival was defined as the time of an event occurrence (death) or censored (patient lost to follow-up) relative to the date of operation. Analyses were performed using SPSS Version 21.

Results

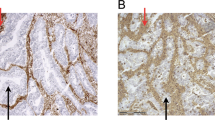

Analysis of tapasin and MHC I expression patterns in normal mucosa and CRC by immunohistochemistry

Tapasin expression in normal tissue was low to moderate; the protein showed a cytoplasmic/membranous expression. The staining was diffuse and homogeneous in the majority of normal and tumor spots. MHC I was downregulated (score lower than the overall mean) in 50.7 % of cases in normal mucosa and in 60 % cases of CRC tumors. Tapasin could be detected in the normal mucosa of 93 % of cases, and was downregulated in 48 % of tumors (p = 0.002). Representative IHC stainings can be seen in Fig. 1. Interestingly, only 2/19 available metastatic cases showed tapasin expression (p = 0.002).

Association of tapasin expression with clinicopathological features and survival in CRC

Reduced tapasin expression was associated with venous invasion (AUC 0.682, p = 0.002, OR 2.70; 95 % CI 1.72–5.0), lymphatic invasion (AUC 0.620, p = 0.005, OR 2.04; 95 % CI 1.25–3.33), and the presence of distant metastasis (AUC 0.727, p = 0.004, OR 2.86; 95 % CI 1.41–5.88). Low tapasin was also concurrent with an infiltrative tumor border configuration (AUC 0.621 p = 0.017, OR 2.22; 95 % CI 1.15–4.35). The associations of tapasin with these and other clinicopathological features are listed in Table 1.

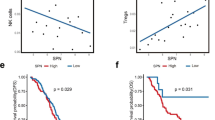

Univariate and multivariate survival analysis

High tapasin expression in the tumor was found to be a significant favorable prognostic factor (p = 0.004, HR 0.6, 95 % CI 0.42–0.85, Table 2). To visualize this effect, we dichotomized the tapasin values using the mean expression score to differentiate between 95 tapasin negative and 103 tapasin positive cases and plotted a Kaplan–Meier curve (Fig. 2). The favorable prognostic effect of tapasin was independently maintained in multivariate analysis when adjusting for potential confounder factors such as patient age and gender, tumor grade, pT, tumor size and location, and adjuvant therapy (p = 0.021). Nevertheless, this effect was lost when pN and pM were added into the analysis (p = 0.327, Table 3).

Tapasin predicts CD8+ CTL tumor infiltration

Next we tested the ability of tapasin expression to predict intratumoral CD8+ CTL invasion, as well as the odds of CTL tumor invasion in the presence and absence of tapasin. Interestingly, a significantly higher presence of intratumoral CD8+ CTLs was found in tapasin-high tumors (AUC 0.729, p < 0.001, OR 5.4; 95 % CI 2.6–11 and AUC 0.650, p = 0.002, OR 2.4 95 % CI 1.4–4.2, respectively, Table 1). Tapasin also increases the likelihood of detecting membranous MHC I expression in tumors by up to two-fold (p = 0.035, OR 1.729, 95 % CI 1.04–2.88). Interestingly, the effects of tapasin on CD8+ CTL tumor infiltration were independent of MHC I membrane expression (p = 0.008, OR 0.615, 95 % CI 0.429–0.882).

Association of tapasin expression and CD8+ CTL infiltration with survival in CRC

To assess whether the prognostic effect of tapasin can be seen as independent of CD8+ infiltration, we added it as a confounder in the Cox regression analysis. Under these conditions, tapasin lost its prognostic effect (p = 0.117). Additionally, we could see no benefit of a combined marker approach (tapasin and CD8+ CTL infiltration, data not shown).

Discussion

The aim of this study was to characterize the expression of tapasin as a potential prognostic tumor marker in CRC. We show that tapasin is decreased in invasive CRC, with this effect being even more pronounced in metastatic tumors. This is consistent with a previous study of tapasin expression in CRC and matched normal tissue, where gradual and increasing tapasin loss was likewise detected with tumor progression [16]. Expression of tapasin is also decreased in many other human cancers, including ovarian carcinoma, melanoma, glioblastoma, and salivary gland cancer [16–20]. We could furthermore correlate reduced tapasin expression with markers of increased invasiveness and systemic spread of the tumor, characterized by increased venous and lymphatic invasion, as well as distant metastasis. Importantly, we identify a strong survival advantage of patients bearing tapasin-positive tumors. Data from other groups have also shown similar consequences of tapasin decrease—in ovarian cancer it has been linked to higher stage, positive lymph nodes and considerably shorter survival time [17]. Likewise, in glioblastoma and salivary gland cancer, reduced tapasin expression correlated with shorter survival times [19, 20]. However, in our study, the prognostic effect of tapasin was lost in a multivariate analysis, indicating that tapasin does not contribute independent information to a prognosis. Lastly we show that tapasin expression correlated with increased membranous staining of MHC I, and as a possible consequence, we detected a drastic increase of intratumoral CD8+ CTLs in tapasin-positive tumors. Interestingly, the effect of tapasin on both CD8+ tumor infiltration and survival is independent of the amount of membranous MHC I. However, this result may be supported by multiple studies showing that tapasin expression not only promotes MHC I cell surface expression but that it increases total antigen presentation efficacy by ensuring the loading of a wide range of stable, highly affine peptides into the MHC I complex [21–24]. Consistent with these data, in a functional mouse study, Lou et al. demonstrated that tapasin expression restored susceptibility of tumor cells to CTL killing, and that animals with tapasin-expressing tumors had increased CD8+ CTL tumor infiltration and better survival [11]. As increased tumor infiltration by CD8+ CTLs has been demonstrated to strongly correlate with survival in CRC [2], we tested whether the prognostic effect of tapasin might be a reflection of its correlation with tumor immune invasion. Indeed, when CD8+ CTL infiltration was added as a confounding factor in a multivariate Cox regression analysis, tapasin did not retain its prognostic effect. These results suggests that the favorable survival effect of tapasin might be mediated both through an increase in antigen presentation quality and quantity. Tapasin expression thereby leads to the activation of the anti-tumoral immune response through increased recognition and infiltration of the tumor by CD8+ CTLs.

The current study has several strengths. It conforms to the criteria for reporting recommendations for tumor marker studies (REMARK guidelines [25]). The analyses have been performed using a very well characterized patient cohort for which full clinicopathological data is available, as well as information on treatment and overall survival. Protein expression was assessed using two tumor center and two tumor front punches in an ngTMA setup, ensuring equal staining conditions for all samples. The main weakness of this study is the lack of mechanistic data. However, the literature on tapasin in the context of immune recognition includes multiple comprehensive in vitro and in vivo functional studies which test the proposed molecular interactions. Therefore, this study focused on evaluating tapasin as a potential prognostic tumor marker in a translational setting.

Conclusions

To conclude, consistent with published functional studies linking tapasin to efficient antigen presentation and tumor immune recognition by CD8+ CTLs, reduced expression of tapasin is associated with tumor progression in CRC. However, our understanding of the role of tapasin in CRC might benefit from testing its expression at the very interface of tumor and immune cells within the tumor microenvironment. MHC I-mediated antigen presentation is frequently downregulated during single cell invasion [14, 26, 27]. Potentially the quality of antigen presentation is also influenced by the conformation of HLA I molecules on the cell surface. Therefore, future studies could include evaluating the functional role and relevance of tapasin expression and MHC I conformation during single cell invasion and its correlation to the immune cell activation in the tumor microenvironment of CRC.

Abbreviations

- IHC:

-

immunohistochemistry

- CRC:

-

colorectal cancer

- CD8+ CTLs:

-

CD8 positive cytotoxic T-lymphocytes

- AUC:

-

area under the curve

- ROC:

-

receiver operating characteristic

- HLA:

-

human leukocyte antigen

- MHC:

-

major histocompatibility complex

References

Jass JR, Love SB, Northover JM. A new prognostic classification of rectal cancer. Lancet. 1987;1:1303–6.

Galon J, Costes A, Sanchez-Cabo F, Kirilovsky A, Mlecnik B, Lagorce-Pagès C, Tosolini M, Camus M, Berger A, Wind P, Zinzindohoué F, Bruneval P, Cugnenc P-H, Trajanoski Z, Fridman W-H, Pagès F. Type, density, and location of immune cells within human colorectal tumors predict clinical outcome. Science. 2006;313:1960–4.

Mlecnik B, Tosolini M, Kirilovsky A, Berger A, Bindea G, Meatchi T, Bruneval P, Trajanoski Z, Fridman W-H, Pagès F, Galon J. Histopathologic-based prognostic factors of colorectal cancers are associated with the state of the local immune reaction. J Clin Oncol. 2011;29:610–8.

Zarling AL, Luckey CJ, Marto JA, White FM, Brame CJ, Evans AM, Lehner PJ, Cresswell P, Shabanowitz J, Hunt DF, Engelhard VH. Tapasin is a facilitator, not an editor, of class I MHC peptide binding. J Immunol. 2003;171:5287–95.

Cresswell P, Ackerman AL, Giodini A, Peaper DR, Wearsch PA. Mechanisms of MHC class I-restricted antigen processing and cross-presentation. Immunol Rev. 2005;207:145–57.

Dick TP, Bangia N, Peaper DR, Cresswell P. Disulfide bond isomerization and the assembly of MHC class I-peptide complexes. Immunity. 2002;16:87–98.

Grandea AG, Golovina TN, Hamilton SE, Sriram V, Spies T, Brutkiewicz RR, Harty JT, Eisenlohr LC, Van Kaer L. Impaired assembly yet normal trafficking of MHC class I molecules in Tapasin mutant mice. Immunity. 2000;13:213–22.

Momburg F, Tan P. Tapasin-the keystone of the loading complex optimizing peptide binding by MHC class I molecules in the endoplasmic reticulum. Mol Immunol. 2002;39:217–33.

Murphy K. Janeway’s Immunobiology. New York, NY: Garland Science, Taylor & Francis Group, LLC. 2011. ISBN: 978-0815345312.

Lou Y, Vitalis TZ, Basha G, Cai B, Chen SS, Choi KB, Jeffries AP, Elliott WM, Atkins D, Seliger B, Jefferies WA. Restoration of the expression of transporters associated with antigen processing in lung carcinoma increases tumor-specific immune responses and survival. Cancer Res. 2005;65:7926–33.

Lou Y, Basha G, Seipp RP, Cai B, Chen SS, Moise AR, Jeffries AP, Gopaul RS, Vitalis TZ, Jefferies WA. Combining the antigen processing components TAP and Tapasin elicits enhanced tumor-free survival. Clin Cancer Res. 2008;14:1494–501.

Koelzer VH, Karamitopoulou E, Dawson HE, Kondi-Pafiti A, Zlobec I, Lugli A. Geographic analysis of RKIP expression and its clinical relevance in colorectal cancer. Br J Cancer. 2013;108:2088–96.

Zlobec I, Koelzer VH, Dawson HE, Perren A, Lugli A. Next-generation tissue microarray (ngTMA) increases the quality of biomarker studies: an example using CD3, CD8, and CD45RO in the tumor microenvironment of six different solid tumor types. J Transl Med. 2013;11:104.

Koelzer VH, Dawson HE, Andersson E, Karamitopoulou E, Masucci GV, Lugli A, Zlobec I. Active immunosurveillance in the tumor microenvironment of colorectal cancer is associated with low frequency tumor budding and improved outcome. Transl Res. 2015;166(2):207–17. doi:10.1016/j.trsl.2015.02.008

Rüschoff J, Nagelmeier I, Baretton G, Dietel M, Höfler H, Schildhaus HU, Büttner R, Schlake W, Stoss O, Kreipe HH. Her2 testing in gastric cancer. What is different in comparison to breast cancer? Pathologe. 2010;31:208–17.

Atkins D, Breuckmann A, Schmahl GE, Binner P, Ferrone S, Krummenauer F, Störkel S, Seliger B. MHC class I antigen processing pathway defects, ras mutations and disease stage in colorectal carcinoma. Int J Cancer. 2004;109:265–73.

Han LY, Fletcher MS, Urbauer DL, Mueller P, Landen CN, Kamat AA, Lin YG, Merritt WM, Spannuth WA, Deavers MT, De Geest K, Gershenson DM, Lutgendorf SK, Ferrone S, Sood AK. HLA class I antigen processing machinery component expression and intratumoral T-Cell infiltrate as independent prognostic markers in ovarian carcinoma. Clin Cancer Res. 2008;14:3372–9.

Dissemond J, Kothen T, Mörs J, Weimann TK, Lindeke A, Goos M, Wagner SN. Downregulation of tapasin expression in progressive human malignant melanoma. Arch Dermatol Res. 2003;295:43–9.

Thuring C, Geironson L, Paulsson K. Tapasin and human leukocyte antigen class I dysregulation correlates with survival in glioblastoma multiforme. Anticancer Agents Med Chem. 2014;14:1101–9.

Müller M, Agaimy A, Zenk J, Ettl T, Iro H, Hartmann A, Seliger B, Schwarz S. The prognostic impact of human leukocyte antigen (HLA) class I antigen abnormalities in salivary gland cancer. A clinicopathological study of 288 cases. Histopathology. 2013;62:847–59.

Belicha-Villanueva A, McEvoy S, Cycon K, Ferrone S, Gollnick SO, Bangia N. Differential contribution of TAP and tapasin to HLA class I antigen expression. Immunology. 2008;124:112–20.

Garbi N, Tan P, Diehl AD, Chambers BJ, Ljunggren H. Momburg F. Hämmerling GJ: Impaired immune responses and altered peptide repertoire in tapasin-deficient mice; 2000. p. 1.

Wearsch PA, Cresswell P. Selective loading of high-affinity peptides onto major histocompatibility complex class I molecules by the tapasin-ERp57 heterodimer. Nat Immunol. 2007;8:873–81.

Rizvi SM, Raghavan M. Mechanisms of function of tapasin, a critical major histocompatibility complex class I assembly factor. Traffic. 2010;11:332–47.

McShane LM, Altman DG, Sauerbrei W, Taube SE, Gion M, Clark GM. REporting recommendations for tumour MARKer prognostic studies (REMARK). Br J Cancer. 2005;93:387–91.

Mitrovic B, Schaeffer DF, Riddell RH, Kirsch R. Tumor budding in colorectal carcinoma: time to take notice. Mod Pathol. 2012;25:1315–25.

Cabrera CM, Jiménez P, Cabrera T, Esparza C, Ruiz-Cabello F, Garrido F. Total loss of MHC class I in colorectal tumors can be explained by two molecular pathways: beta2-microglobulin inactivation in MSI-positive tumors and LMP7/TAP2 downregulation in MSI-negative tumors. Tissue Antigens. 2003;61:211–9.

Authors’ contributions

LS scored immunohistochemistry, performed statistical analysis and data interpretation and conceived and drafted the manuscript; VHK conceived the study and study design, scored immunohistochemistry and performed manuscript editing; IZ conceived the study and study design, scored immunohistochemistry, performed manuscript editing and reviewed statistical data interpretation, TTR reviewed data interpretation; EK reviewed cases, organized the patient cohort, provided clinical data and evaluated the immunohistochemistry. AL evaluated the immunohistochemistry, reviewed the study and study design, discussed the data and performed manuscript editing. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Compliance with ethical guidelines

Competing interests The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Funding source

This project was funded by the Bernese Cancer League and Oncosuisse. The funding source had no influence on the study design, analyses or interpretation of the results presented in the paper.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

Lena Sokol and V. H. Koelzer equally contributing first authors

Additional files

Additional file 1:

Figure S1. Study design, including patient number, and clinical and histopathological information overview. 220 CRC patients with full clinicopathological information were entered into the study. The association of tapasin with clinicopathological features and MHC I were analyzed using a multi-punch next generation tissue microarray.

Additional file 2:

Table S1. Patient characteristics (colorectal cancer patient cohort, n = 198, max). Clinicopathological features of the 198 patients for which tapasin expression could be analyzed.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made. The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver (http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/) applies to the data made available in this article, unless otherwise stated.

About this article

Cite this article

Sokol, L., Koelzer, V.H., Rau, T.T. et al. Loss of tapasin correlates with diminished CD8+ T-cell immunity and prognosis in colorectal cancer. J Transl Med 13, 279 (2015). https://doi.org/10.1186/s12967-015-0647-1

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s12967-015-0647-1